Comments

-

Ukraine CrisisYou realise that the concept of 'agreement' implies two (2) entities agreeing on something, right?

— Olivier5

Yes. The supplicant and the enforcing power. Neither need be a state. — Isaac

Not sure you are referring to here. What "enforcing power" do you have in mind, and what "supplicant"? The latter term is odd in the context of a negotiation between equals. -

Ukraine Crisisstatement "I believe that Russia ought to be in control of all the land up to the Dnieper, but I agree not to shoot or bomb anyone in that area nonetheless". How is that not a peace agreement? — Isaac

You realise that the concept of 'agreement' implies two (2) entities agreeing on something, right? -

Ukraine CrisisAcknowledgement of the existence of spurious entities such as 'states' is not a requirement for peace. — Isaac

It is a requirement IFF you want to make peace with said entity. Logically speaking, you cannot make peace with a non existing entity, can you? -

Ukraine CrisisYou can't make peace with someone without acknowledging the existence of said someone. So when Russia signs a peace deal with Ukraine, it will have to recognise Ukraine as a fact.

My sense is that such peace deal will include a right of return for all Ukrainians presently in Russia, whether willingly in Russia or brought there against their will. Children included.

Russia is apparently more interested in snatching people than in stealing land. But in the end they will have to return both. -

Ukraine CrisisIn liberated Kherson, residents between jubilation and disbelief

After eight and a half months of Russian occupation, the Ukrainian forces were greeted with emotion by the population of this city in the south of the country.

By Rémy Ourdan for Le Monde (Kherson)

Posted today at 06:57, updated at 09:12

The fog of dawn still envelops Kherson when the first inhabitants appear on Freedom Square, only about twenty at first. Few of them had the privilege to participate in the first celebrations of the city's liberation, the evening before, dancing around a brazier. Many, in Kherson cut off from the world, heard only a distant and uncertain echo of the historic event of November 11, through the stories of neighbors, or because they saw, in their street, a column of Russian soldiers leaving or Ukrainian fighters entering the city.

The first visual confirmation of the recapture of Kherson by the Kiev armed forces, for these people who had no access to television or social networks during the night, comes at dawn on Saturday 12 November: a Ukrainian flag is planted in Freedom Square, in front of the deserted building of the regional administration. It floats in the wind on what was a monument dedicated to the heroes of the Maidan revolution, destroyed by Russian forces in the first days of military occupation.

There are also these four police officers on duty around a van, who seem to be wondering what they are doing there, alone at this early hour, in a city which the Ukrainian general staff fears is still infested with plainclothes Russian agents, or soldiers from Moscow who missed the hour of departure before the bridges connecting it to the other bank of the Dnieper were cut.

A first military jeep appears in the fog. Three special forces commandos emerge, bearded, drawn features. Immediately grabbed by the inhabitants, entwined, congratulated, they quickly put on a smile that had perhaps disappeared from their face over the months of fierce fighting. The three fellows, in control of their emotions, seem almost surprised by the intensity of the welcome, by the gestures and the words of these Ukrainians who cling to them as one would cling, after a long time under water, to a lifeline.

"Surreal"

“Are you real? ! asks a woman . She wants to touch them, kiss them. Another woman brings yellow and blue ribbons – the colors of Ukraine – from her shop. People ask soldiers to write a word on them with a black marker, then wrap them around their wrists or pin them to their coats. On the other side of the square, men hoist a flag on the roof of the Ukraine cinema. "These Ukrainian flags everywhere, I can't believe my eyes" , a lady is moved.

The central square is gradually filling up. The soldiers of the 28th Mechanized Brigade, at the forefront of the battle for the reconquest of the Kherson region, arrive at the city center. Then there are the police forces. After eight and a half months of occupation, suffering, silence, emotion overwhelms Freedom Square. The people of Kherson are in tears. Young girls hug the soldiers. Children wave flags. Everyone wants a hug, a shoulder to rest on for a second, a smile to share.

In a city without electricity, without water, without phone, everyone takes out a cell phone with a miraculously charged battery and takes pictures. Memories to look back on later. "As soon as the phone network is restored, I will send these pictures to my children abroad," says one woman. "You won't have to wait too long," smiles the special forces officer. He orders a soldier to deploy three Starlink antennas in the square. After a few minutes, the first phones begin to vibrate, releasing jams of waiting messages. The satellite network is so quickly taken over that it quickly becomes overwhelmed, impossible to make any call or send a picture. No matter. It's time for joy.

In the center of Freedom Square, one takes pictures in front of the destroyed monument, where residents lay flowers in tribute to those who fell in 2014 for the independence of Ukraine. In front of the Ukraine cinema, waiters at Topy, the only café open in a ghost town where all the curtains are down, take out five tables on the terrace and start serving hot tea and coffee. "It's surreal..." murmurs a young man. "It's almost as if this is peace, normal life."

A humiliating retreat for the Moscow army

Some inhabitants, seeing the presence of a journalist, start to spontaneously evoke the months of occupation, "the fear of the Russians", "the lack of everything", "the wait for the return of our guys". A woman is indignant: "Why is Putin doing all this? Why this war? Ask him this question in your newspaper!" Another tells us that "the Russians stole everything, the food in the stores, the books in the libraries, the carpets in the wedding hall, and even the little train in the kindergarten!"

Although it was less sudden than in the Kiev region and less chaotic than in the Kharkiv region, the retreat from Kherson was just as humiliating for the Moscow army. It marked the third bitter failure of the Russian war in Ukraine, while the city, conquered on 2 March, was the only Ukrainian regional capital to have passed under Russian control.

Zhanetta, a doctor whose apartment overlooks the square, saw "these checkpoints where Russian soldiers were stopping men, searching cars, searching phones." "The Russians said they were there 'forever'. We looked at them from our windows, without saying anything. We were waiting for our soldiers so impatiently," she says in a choked voice.

Anton, a young photographer who aspires to work for the press, was unable to document the occupation. "I was too scared. I only left my house twice in eight and a half months," he says. Once to see a friend downstairs. The other time, it was to try to flee Kherson, towards the territory under Ukrainian control. We went through about 30 checkpoints and at the last one, the Russian soldiers wouldn't let us through. It was a terrifying journey." Olga, a young psychologist who specializes in medical checkups for sailors in the port of Kherson, also didn't venture onto the streets of her city during the occupation. "The Russians came once to search my house. Then I stayed at home with my parents."

"This is the best day of my life!"

A man parks an old black Soviet-era Pobeda at the curb. Strollers gather to admire the antique. The car is equipped with six speakers, and it blasts I Have Nothing by Whitney Houston. "Don't walk away from me/I have nothing, nothing, nothing/If I don't have you," Whitney sings. "You, Ukraine," sing the young people surrounding the car.

Olga shares a bottle of "Ukrainian champagne" with another woman. They drink from the bottle, like so many others in Freedom Square. "This is liberation. This is the best day of my life," says one man. Some begin to improvise dances. The Ukrainian anthem aside, the most popular tune is Chervona Kalyna ("Red Berries"), an old song that rocker Andriy Khlyvnyuk "Boombox" covered in the days after the Russian invasion and which became a rallying song of the Ukrainian resistance. Soldiers' jeeps that continue to drive through Kherson also play it. The crowd is waving flags and singing at the top of their lungs.

Shortly before sunset, the three guys from the special forces leave. The back of their pick-up has become a kind of altar covered with offerings: flowers, chocolate bars, children's drawings... Those of the 28th Brigade also leave, followed by the policemen. They return to their bases, away from the city. Oleh, a police special forces fighter, is one of the last to sign flags and ribbons. "I have no words to express what I feel, my emotion," he says modestly. I am from Kherson. This is my hometown, I used to live here." Oleh does not want to talk about his departure in February, or his war. Another day, perhaps. "Please, write 'Glory to Ukraine' on this flag," a little girl asks him.

Night falls. In the distance, Ukrainian artillery fires a salvo of shells. The war is not over," says a soldier. Our comrades are on the front, advancing towards other territories to be liberated. We have received orders to spend a day or two in Kherson to see the population, but tomorrow we join them." In the darkened city, the girls stop dancing. "I am a little afraid that the Russians will punish Kherson for being so happy," says Natalya. Liberation is good, but it is not yet peace. -

Ukraine CrisisYou're free to do what the king says! — boethius

You know as well as I do that the Ukrainians are much freer than the Russians. -

Ukraine CrisisYou can't ban the opposition parties, ban dissenting media, ban people leaving the country, impose marshal law (i.e. no due process), and then call what you have "freedom". — boethius

The opposition paries are not banned.

Only one of the main opposition parties was banned (Opposition Platform). It was an openly pro-Russian party that maintained close ties with Russian officials and Russian ruling party before the invasion. (One of its leaders, Viktor Medvedchuk, has longstanding personal ties to Vladimir Putin. After he was arrested on treason charges, Putin had him exchanged for over 200 Ukrainian prisoners, including all of Azov commanders, as well as foreign prisoners who were sentenced to death in Donbass. That provoked a lot of anger among Russian war hawks.)

It should also be noted that although the parties themselves were banned, their elected representatives were not ejected from legislatures, and members of local governments from those parties continued in their capacities. (Unlike, for example, members of the banned British Fascist party, who were interned until the end of the war.) The Opposition Platform simply renamed its faction in Ukraine's parliament. — SophistiCat

Likewise, only pro-Russian media, were banned, not all independent media, and people can leave the country as much as they want if their aren't men of a certain age cohort. -

Ukraine CrisisNone of the critical fundamental freedoms (freedom of speech, freedom of movement, freedom to associate etc.) are currently available in Ukraine — boethius

That's just another blatant lie. -

Ukraine Crisis↪Olivier5, according to the Kremlin, Ukraine is now occupying Russian territory — jorndoe

Yes but then, according to the same Kremlin buffons, there is no war in Ukraine... -

Ukraine CrisisKherson is free. That was fast .

Ukraine is "almost in full control" of Kherson according to Yuriy Sak, an adviser to Ukraine's defence ministry.

Cheering crowds greeted Ukrainian troops as they arrived in the only regional capital to have been captured by Russian forces since its invasion in February.

Earlier, Ukrainian flags appeared in Kherson after Russia said it had completed the withdrawal of thousands of troops.

But Sak says some Russian soldiers left in the area are taking off their military uniforms, and trying to blend in with locals.

The Kremlin's spokesman meanwhile rejects that losing the key southern city is a humiliation for Vladimir Putin.

Source: BBC -

Ukraine CrisisSo a bunch of unknown dudes off the Internet guessestimated that there is a 9% chance a nuclear warhead is detonated in Ukraine or Europe over the next 6 months. What does that mean?

The figure is just a guess, nothing more.

The important point is not in the number 9. It is that this war has increased the risk of nuclear escalation, compared to pre-february level. And it is now not negligeable. It follows that this war cannot continue for several years without running a significant risk of nuclear escalation.

I agree with their forecast, interpreted as such. -

Ukraine CrisisVoices from the trenches: Ukrainian soldiers near Kherson share what they feel and fear

— The Kyiv Independent; Nov 9, 2022 — jorndoe

Nice piece. This journalist, Igor Kossov, seems pretty good. I’ll follow him from now on. -

Ukraine CrisisAlso crossing the Dniepr is a big difficult operation for Ukraine. — ssu

Yes, and that’s what the Russian top brass is counting on: a more defensible position, from which they can bomb Kherson to the ground. Reason for which they emptied it, and even took with them the remains of Potemkin. They want to flatten the town while fixing the Ukrainian forces on the right bank of the Dniepr. -

Deep SongsThere is no such thing as a happy love

Poem: Louis Aragon - Music: Georges Brassens

Man can take nothing for granted, neither his strength

Nor his weakness, nor his heart. And when he believes

He open his arms, his shadow is that of a cross

And when he tries to clutch his happiness, he crushes it

His life is a strange and painful divorce

There is no such thing as a happy love

His life is like those unarmed soldiers

Who were dressed for another fate

What use is it to them to get up in the morning?

They are found in the evening, unarmed, uncertain

Say these words, my dear, and hold back your tears

There is no such thing as a happy love

My beautiful love, my dear love, my fracture

I carry you inside me like a wounded bird

And others, without knowing, are watching us go by

Repeating after me the words that I've woven

And which, for your wide eyes, immediately died:

There is no such thing as a happy love

By the time we learn how to live, it's already too late

Let our hearts cry in the night, in unison

How many regrets to pay for the slightest thrill

How much sorrow it takes to write the shortest song

How many sobs to compose a guitar tune?

There is no such thing as a happy love

There is no love that is without pain

There is no love that doesn't end bruised

There is no love that withers not

And no more than for you, the love of the country

There is no love that does not live on tears

There is no such thing as a happy love

But it's love we got, you and me

-

Ukraine Crisisbut you know, they did forget to consult a couple of messianic dicks off the internet, so perhaps just "some knee-jirking western pundits" after all, eh? — Isaac

Those experts are not on the Internet yet? You found about them how? -

Ukraine CrisisThere's no actual 'nuclear ransom' here. Putin himself ruled out the use of nukes in Ukraine. Of course an escalation is always possible, but it is not actually being branded as a threat by the big boy himself.

At this stage, nuclear escalation is an emotional fantasy entertained by some low-level bureaucrats and angry pundits in Russia, and by some knee-jirking western pundits.

I won't build a nuclear shelter in my garden just yet. -

Ukraine CrisisNevertheless, either side is capable of blowing up this dam at any time. The immediate result would be a wall of water carrying debris cascading down the Dnipro valley washing everything in its path into the Black Sea. — magritte

There's indeed that threat. The theory is that the Russians leave Kherson only to flood it once the Ukrainians step in. But the terrain in Kherson is not favorable to such a plan. The left bank is much flatter and lower than the right bank, so the Russians there would be flooded, not the Ukrainians. -

Ukraine Crisisincapable of basic comprehension as you were 300 pages ago. — Isaac

That'd be because you wallow in ambiguity like a pig in his mud. But here too, you seem to be making progress. :-) -

Ukraine CrisisI don't buy for a second that he's actually concerned about Nazis. — Isaac

You're making progress. -

Ukraine CrisisThanks for the maps.

Reuters give some more detail: they cannot supply Kherson well enough for its defence; they are afraid to lose too many men for nowt.

Russia abandons Ukrainian city of Kherson in major retreat

By Mark Trevelyan

LONDON, Nov 9 (Reuters) - Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu on Wednesday ordered his troops to withdraw from the occupied Ukrainian city of Kherson and take up defensive lines on the opposite bank of the River Dnipro.

The announcement marked one of Russia's most significant retreats and a potential turning point in the war, now nearing the end of its ninth month.

In televised comments, General Sergei Surovikin, in overall command of the war, reported to Shoigu that it was no longer possible to keep Kherson city supplied.

"Having comprehensively assessed the current situation, it is proposed to take up defence along the left (eastern) bank of the Dnipro River," said Surovikin, standing at a lectern and indicating troop positions on a map whose details were greyed-out for the TV audience.

"I understand that this is a very difficult decision, but at the same time we will preserve the most important thing - the lives of our servicemen and, in general, the combat effectiveness of the group of troops, which it is futile to keep on the right bank in a limited area." -

Ukraine CrisisThat could be a big victory for Ukraine, or a trap:

Moscow orders retreat from Kherson

The Russian defense minister ordered on Wednesday, November 9, the withdrawal of Russian forces from the right bank of the Dnieper River in the Ukrainian region of Kherson, which includes the regional capital of the same name, target of a large Ukrainian counter-offensive for several weeks.

"Proceed with the withdrawal of soldiers," Sergei Shoigu said on television, after a proposal to this effect by the commander of Russian operations in Ukraine, General Sergei Surovikin, who acknowledged that it was a decision "not at all easy" to take. "The maneuvers [of withdrawal] of soldiers will begin very quickly," assured the general.

The announcement was received with skepticism in Kiev. "We see no sign that Russia is leaving Kherson without a fight. Part of the Russian [troops] is still in the city" in southern Ukraine, said a presidential adviser, Mykhailo Podoliak, blasting "staged television statements" from Moscow.

https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2022/11/09/guerre-en-ukraine-moscou-ordonne-le-retrait-des-forces-russes-de-la-ville-strategique-de-kherson_6149238_3210.html -

Ukraine Crisisthe example would be: Germany, Italy, Japan after WW2. — neomac

You could throw in the whole of Europe after WW2. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Not because he thinks it's a good idea for the US but because it is an imminently bad idea. If even Putin recognises that, you'd think it was a hint but since US media is mostly intent at gazing at its own belly button, nobody is aware voting Republican weakens the US. — Benkei

Indeed, republicans and anyone voting for them are destroying the US. Especially their crass, totally anti-american rhetoric of constant lies and hatred. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)It's funny how no one anywhere but in the US would ever consider voting Republican. The US political system is a tragedy. — Benkei

Mr Putin did vote for Republicans, though. -

Ukraine Crisis

Note that contrary to you in that older exchange, I just did explain clearly and simply what my position was as soon as your confusion about it became apparent. -

Ukraine CrisisYou conveniently ignored the empirical part of my post, which was:

And that is the case with the number of deaths attributable to the conflict outside Ukraine: nobody cares to count. In fact, a reliable body count does not even exist inside Ukraine. — Olivier5

It's not my fault if you are wasting your time chasing windmills. Next time try and understand what I say rather than shoot first and think later. -

Ukraine CrisisGovernments, NGOs, corporations, don't just make random guesses as to the impact of their interventions. — Isaac

LOL. They do do guess, not totally randomly of course. Sometime they don't even care to guess. Someone has to pay for the info, otherwise why collect it? And that is the case with the number of deaths attributable to the conflict outside Ukraine: nobody cares to count. In fact, a reliable body count does not even exist inside Ukraine.

I never ever professed such an opinion.

— Olivier5

Yeah, right. — Isaac

That is correct. Countries that help Ukraine do so for all sorts of reasons and might stop their support whenever they feel like the cost is too high, or some other reason. My point, instead, is that the belligerents are the ones deciding when to stop the war, and how and when to negotiate to that end. -

Ukraine CrisisThe damage. As I've explained above. The costs are measured in millions of lives. — Isaac

The cost is not actually measured. You are talking of an economic theory, which is to say that everything and every countries are connected, and thus some consequences beyond Ukraine and Russia are to be expected. The poor worldwide will suffer the global consequences. But how many and by how much is not being measured. Whatever methodology one cooks up for doing so would be awfully complex, and open to many criticism.

Because you see, the world poor also suffer from the consequences of millions other things, first among which comes disenfranchising in their own country. Their lack of political and legal rights lays at the root of the problem. Poverty is powerlessness.

Regardless, this is about your claim that it is proper only to consider the opinion of Ukrainians when deciding whether to continue funding the war. Are you now going back on that position? — Isaac

Not at all, for the very simple reason that I never ever professed such an opinion. -

Ukraine CrisisThat's not having a say in whether the war is worth it, is it? — Isaac

Worth what?

At what point did the US consult the African Union about the impact of their continued funding for the war — Isaac

The voices of Africa are heard in the UN General Assembly, among other places. Only half of them voted for the UN resolution condemning the Russian invasion in March. This sent a message. -

Ukraine CrisisThe war in Ukraine severely increases the risk of starvation for millions in Africa by

increasing the cost of fuel

reducing supplies of fertilisers

limiting the supply of drugs

risking further disruptions to food exports

risking the loss of food supplies next year

detracting donor attention from vital humanitarian aid

Simple question - do those millions at risk of starvation because of the continued war get a say in whether it's worth it or not? — Isaac

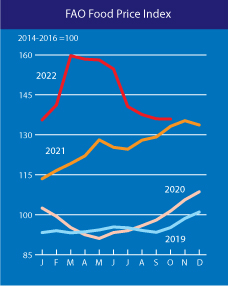

Why yes they do. Macky Sall, the president of Senegal and acting chair of the African Union,, pushed for the cereal export deal brokered by UNCTAD and Turkey. By visiting Moscow, he made sure Africa had a say. This deal is credited to bringing food prices down to pre-war levels:

-

Ukraine CrisisThis from UNICEF in October. It's not enough.

James Elder, a spokesman for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), told reporters in a video call from Somalia on Tuesday. “Without greater action and investment, we are facing the death of children on a scale not seen in half a century.” — Isaac

It won't surprise our most faithful readers who know you as a serial liar, but this Unicef quote has nowt to do with Ukraine. This quote is from a press release about Somalia and does not mention Ukraine.

https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-warns-unprecedented-numbers-child-deaths-somalia

I understand that for the putinistas, the Ukrainians are responsible for all the world's problems, and their identity needs to be erased otherwise the universe will crumble. But don't erase the identity of Somalians in the process! -

Ukraine CrisisNo one has so many "friends and brothers" on the front that they can personally accumulate a first hand overview of the strategic position. — Isaac

I am not talking of getting an overview of the strategic position, though. -

Ukraine CrisisBut possibly no better informed than US intelligence. — Isaac

Speculative.

Only a tiny handful if Ukrainians have a sufficiently large social circle to gain anything more than a tiny vignette of what's going on directly. The rest they obtain from media reports, same as us. — Isaac

I would think that this is false. They live through this war, and have friends and brothers on the front.

I don't think that has a clear answer. — Isaac

So your question was unclear then, since what constitutes "the whole strategic situation" remains unclear. -

Ukraine Crisis↪Olivier5

As Benkei said...

I don't trust the news in normal times and actively distrust it in war times.

— Benkei

...or did you go to Ukraine yourself, talk to the soldiers there, gather that intelligence directly... You must get up very early in the morning to get all that done. — Isaac -

Ukraine Crisisthe desperate, terrifying and bloody circumstances of the soldiers on the front line are hardly good conditions from which to get a good strategic overview. That's why armies have intelligence units and a command structure. — Isaac

Indeed. But then, aren't these Ukrainian intelligence units and command structure better informed than you and me?You're trying (and failing) to make the case that they're better informed. I'm not making the case that they're less well informed. — Isaac

I am not trying to make a case here, it just seems obvious to me, that's all.

on top of their capacity for direct observation and interview.

— Olivier5

Which is miniscule compared to the size of the population. Journalists have access to direct observation and interview too. — Isaac

A capacity for direct, primary observation is generally held in higher regard epistemologically than the capacity to read secondary data in the newspaper.

It doesn't give them any better an overview of the whole strategic situation. — Isaac

What would you call "the whole strategic situation" exactly? Where does it start and end? And who has got a good view of it? God? -

Ukraine CrisisOne of the few civilians left in Kherson describes his daily struggle to survive under Russian occupation and keep the dream of liberation alive.

By a resident of Kherson, as told to Kseniia Kelieberda and Miranda Bryant for The Guardian

Sun 6 Nov 2022 01.00 EST

More than eight months after Kherson’s capture by Russian soldiers, the city is heavy and gloomy. Everything is frozen, hidden. After 3pm, there are no people on the streets. In the morning they go out to buy groceries and then they sit at home.

Kherson is being robbed by the Russians. Everything is taken out: monuments to Suvorov, Ushakov, Potemkin and Margelov were removed from their pedestals; barges, fire engines, ambulances and office chairs. They break into apartments. Even the windows of the city hall have been removed. A total organised plunder of the city is under way. Cars carry loot to the river and from there they are transported by boats to the left bank.

A car with a loudspeaker drives around the city urging residents to leave and text messages are sent during the night. But, like me, many of my friends stayed. We buy food and store water. We do not believe in forced evacuation. People are said to be taken to remote regions of Russia – but these are rumours.

There is practically no internet in Kherson. Communication has disappeared and even Russian TV channels have stopped broadcasting. That’s why there are so many rumours. We hear Ukraine’s artillery duel with Russia and we wait for release.

Russian soldiers can stop you on the street and detain you. They can break into your apartment and take anything.

I’m used to living like this. I’m feeling philosophical.

In some ways, the living conditions are normal. There is water and electricity, heating works, rubbish is taken out. There is food, but food prices are rising daily. Some shops and hospitals are closed. Although medical equipment has been removed, I read on Facebook that the doctors of the city’s first maternity hospital are delivering babies. Somewhere they found an old gynaecological chair, tools and medicines, and they work. In war, too, children are born. Three pharmacies remained in Kherson. The rest were evacuated. I don’t need medication. I do not complain about my health.

For the past few months, I have been preparing food for the winter. Occasionally, I meet colleagues at work, acquaintances. If there is internet, I advise employees. Sometimes I go to the dacha. I’m reading – mostly fiction and memoirs – and improving my culinary skills. Last Thursday, I met a colleague and went to the grocery store. While I cooked, I talked with relatives. In the evening, I read for two or three hours. Last week, I made 11 litres of grape juice with grapes I picked at the dacha. It took over six hours. In the occupied city, the days go by slowly and monotonously. You need to find something to do.

I don’t feel safe. Russian soldiers can stop you on the street and detain you. They can break into your apartment, search it and take away anything. My apartment has already been searched and we were detained at the dacha, which is near the Antonovsky railway bridge. They thought that we were gunlayers. They beat me up and threw me in jail. They took away my travel equipment – backpacks, tent, money, a phone and a laptop – but nothing incriminating was found and they released me a day later under house arrest. Now the city is in chaos. I will go to the dacha again, to help my friend move to the right bank. Everyone who lives in the dachas have been told to leave by the end of the week.

Those who wanted to leave Kherson and could, left. But we did not have humanitarian corridors and organised evacuation to Ukrainian territory. To leave was either very expensive or you needed your own car. Those who couldn’t afford to leave stayed in Kherson.

All my pro-Ukrainian acquaintances ignored Russia’s “evacuation”, which was mainly used by collaborators and their families, and those who were frightened by their false claims that Ukraine would blow up Kakhovka hydroelectric power station and attack Kherson. This is a journey into the unknown.

I believe that “evacuation” is a voluntary deportation of the population. Blackmail and intimidation of people are used. People were transported by boats across the Dnieper, and then they were transported by buses. We don’t know where these people are. There are various rumours.

I’m not hiding. I live in my apartment. I’m not alone. My cat, Hunter, lives with me. There is a family Telegram chat where every morning there is a roll call – they write to me from Kyiv, Chernivtsi, Bucharest. If there is a connection, I talk to them.

We know what’s going on with everyone.

There are few civilians left in Kherson now. I think 25% to 30%. I live in a multistorey building with 260 apartments. In the evening, no more than 20 windows are lit. Before the war, about 350,000 people lived in Kherson.

Soon, I think the right-bank part of the country will be liberated and that Ukraine will win. I am preparing to fight. I have built up food and water stocks, prepared the gas burner and decided on a reserve place to live. I stocked up on Hunter’s food as well. It is very hard to wait but I believe in liberation. I think it will happen this month.

Life has changed dramatically since Russia’s invasion. For people in occupied Kherson, the main thing now is to survive. I think about what will happen after the war.

When the occupation is over, I dream of seeing all my relatives and friends and returning to a peaceful life. I want to work, relax, travel. Faith in the imminent liberation of the city is keeping me going.

We want to create a family agricultural company and I will definitely go to the Camino de Santiago with my wife. Maybe someone else will join us, too. We had planned to do it back in 2020. But the pandemic happened, then the war. In the 21st century, only bloodthirsty savages are capable of this. They have no place in the civilised world. -

Ukraine CrisisYes. But your average Ukrainian is not visiting the front line, nor are they visiting the negotiation rooms in Parliament, so the analogy is irrelevant. — Isaac

Quite a few Ukrainians of both sex are "visiting" the frontline.

There are journalists, intelligence agents and amateur social media posters who all have a better grasp of the situation in those two areas than the average Ukrainian. They publish their information online for anyone to read. — Isaac

But all these sources like ISW are available to Ukrainians too, on top of their capacity for direct observation and interview.

It tells me how hard the citizens of Bakhmut are finding it to survive. — Isaac

Still, the citizens of Bakhmut know better about it. -

Ukraine CrisisBy what mechanism? — Isaac

Pushing the idea at an extreme so that you can fathom it: if you were visiting planet Kepler-186f, landing on it and exploring it, don't you think you'd have a better feel for it than from your average living room in Wigan or Trenton? -

Ukraine CrisisMillions are facing starvation because of this war, and thousands of rich Ukrainians will remain completely untouched by it, including many of those actually making decisions. Wars don't affect people on the basis of what fucking passport they carry. They affect, unsurprisingly, the poorest, the working class. And they affect whomever they touch, passport or no. — Isaac

This is a very general statement. You want to make it more specific, otherwise it's not empirically or logically testable. What's the actual proposition here? Like, that poor people worldwide are going to suffer from high food and energy prices? So Ukrainians should lay down arms and submit to Putin so as to help Africans?

Olivier5

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum