Comments

-

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaYou had said he puts mind at the center of reality, and language at the center of mind. That's why I thought the ultimate relationship would be mind to world. No? — frank

When Wittgenstein at the start of On Certainty discusses GE Moore and the statement "I know that here is a hand", perhaps one can say that Ayer's centre of interest is the relationship of mind to world and Austin's centre of interest is the relationship of language to world.

For Ayer, we know of the hand through our sense data independently of language. For Austin, we know of the hand through our language, independently of any world that may or may not exist independently of our mind.

In this sense, there are similarities between Austin and the later Wittgenstein, in that for both of them the main interest is in language. Their interest is not in Ayer's metaphysical considerations of the relationship between the hand that I know exists in my mind to a hand that may or may not exist in a world independently of my mind. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaI see. So Austin doesn't want sense data because it interferes with the way he envisions the relationship between mind and world? — frank

Perhaps more the relationship of language to world. Don't you agree? Reference to sense-data is not generally used in ordinary language, as when he writes:

For reasons not very obscure, we always prefer in practice what might be called the cash-value expression to the 'indirect' metaphor. If I were to report that I see enemy ships indirectly, I should merely provoke the question what exactly I mean.' I mean that I can see these blips on the radar screen'-'Well, why didn't you say so then?' -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaCould you explain what that is? — frank

To my understanding, as Austin's interest is in language, it is not surprising that he challenges the sense-data theory that we never directly perceive material objects, as this is not how language works. In language, we do directly talk about material objects.

Linguistic Idealism may be described as the position that puts the mind at the centre of reality and language at the centre of the mind, and language does not represent the physical world as is often claimed but is the world itself. (www.researchgate.net - Nonrepresentational Linguistic Idealism). Wittgenstein has sometimes been described as a Linguistic Idealist. GEM Anscombe considered the question whether Wittgenstein was a Linguistic Idealist in her paper ‘The Question of Linguistic Idealism’.

Basically, the sense-data theory of Ayer and the linguistics of Austin are different aspects of knowledge, as mathematics and ethics are different aspects of knowledge. That is not to say neither is not valid, but becomes problematic when mixed up together. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaHe emphasises linguistic usage must be centred from ordinary people's usage, not philosophers' — Corvus

As I see it, in Metaphysics, the Indirect Realism of Ayer is the more sensible approach. In Linguistic Idealism, the Direct Realism of Austin is the more sensible approach. As Austin is speaking from a position of Linguistic Idealism, Sense and Sensibilia should be read bearing this in mind. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI suppose there’s nothing inherently wrong with naming an existence as such. But naming a mere existence doesn’t tell me as much as naming the object of my experience. — Mww

I have an experience which has the name "the colour red". I know that this experience has had a cause, but although I don't know what the cause was, I do know that the cause existed. I can name this unknown cause "A". I can then talk about the cause of my seeing the colour red as "A" and the cause of my seeing the colour green as "B". I don't know what "A" and "B" are, other than that they exist. Something that is unknown yet exists can be named as a "thing-in-itself". Both "A" and "B" are things-in-themselves.

It is true that the names "A" and "B" don't tell me as much as the names "the colour red" and "the colour green", but they do tell me something, that "A" and "B" exist and that "things-in-themselves" exist. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismThere is also the humoncular regress to consider. If we "see representations" by being "inside a mind" and seeing those representations "projected as in a theater," then it seems we should still need a second self inside the first to fathom the representations of said representations, and so on. Else, if self can directly access objects in such a theater, why not cut out the middle man and claim self can just experience the original objects? — Count Timothy von Icarus

We can avoid the homuncular regress by acknowledging that the self is not separate to the representations but the self is the representations.

Questions about freedom are questions about: "to what extent we are self-determining as opposed to being externally determined.".............We can be alien to ourselves...............We can identify with and exercise control over what determines our actions. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This raises the question of how we can be self-determining. We say, "I think I will have a coffee rather than a tea". Such a thought did not exist at a prior moment in time, so what caused the thought to come into existence. Either a prior state of affairs, which is Determinism, or the thought itself caused itself to come into existence, which is Free Will.

How can something cause itself to come into existence? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismSay it is the case thing-in-itself is a name. What am I given by it? What does that name tell me? — Mww

That it exists. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismNot as I understand it.The indirect realist does not and knows it; the direct realist does not but thinks he does.................Yes, which fits with what I just said, but doesn’t fit with both seeing a red postbox......................No human can see with his eyes closed. — Mww

There are at least two aspects to the question of Indirect and Direct Realism, the metaphysical and the linguistic. When considering an expression such as "I see the red post-box" the metaphysical and the linguistic should not be conflated

As regards the metaphysical, Indirect Realism makes more sense than Direct Realism. We know that when an object emits a wavelength of 700nm we see the colour red. The Indirect Realist would argue that the colour red exists in our minds. The Direct Realist would argue that the object is red.

As regards the linguistic, Direct Realism is more appropriate than Indirect Realism. As Wittgenstein discusses in Philosophical Investigations and On Certainty, words exist within language games, and within language games are certain hinge propositions on which the language game is founded. These hinge propositions are always true within the language game of which they are part. They are not intended to correspond with the world they describe, but create the world that they describe, in that the proposition "I see a red post-box" is true even if in the world is a flying pink elephant.

When considering the proposition " I see the red post" linguistically rather than metaphysically, it should be remembered that any particular world may have many different meanings. For example, according to the Merriam Webster dictionary, the word "see" as a transitive verb may mean:

1 a = to perceive by the eye

b = to perceive or detect as if by sight

2 a = to be aware of : RECOGNIZE - sees only our faults

b = to imagine as a possibility : SUPPOSE - couldn't see him as a crook

c = to form a mental picture of : VISUALIZE - can still see her as she was years ago

d = to perceive the meaning or importance of : UNDERSTAND

3 a = to come to know : DISCOVER

b = to be the setting or time of - The last fifty years have seen a sweeping revolution in science

c = to have experience of : UNDERGO - see army service

4 a = EXAMINE, WATCH - want to see how she handles the problem

b = READ - to read of

c = to attend as a spectator - see a play

5 a = to make sure - See that order is kept.

b = to take care of : provide for - had enough money to see us through

6 a = to find acceptable or attractive - can't understand what he sees in her

b = to regard as : JUDGE

c = to prefer to have - I'll see him hanged first.

7 a = to call on : VISIT

b (1) = to keep company - had been seeing each other for a year

(2) = to grant an interview to : RECEIVE - The president will see you now.

8 = ACCOMPANY, ESCORT - See the guests to the door.

9 = to meet (a bet) in poker or to equal the bet of (a player) : CALL

The word "see" as an intransitive verb may mean:

1 a = to apprehend objects by sight

b = to have the power of sight

c = to perceive objects as if by sight

2 a = to look about

b = to give or pay attention

3 a = to grasp something mentally

b = to acknowledge or consider something being pointed out - See, I told you it would rain.

4 = to make investigation or inquiry

===============================================================================

the direct realist should be able to name the red postbox even if he didn’t even know what a red postbox was. — Mww

As I don't know the Arabic name for "red post-box" without having first learnt it, the Direct Realist cannot name an object without having first learnt its name.

===============================================================================

The indirect realist conceives the color red as one of a multiplicity of properties belonging to the phenomenon representing the thing he has perceived. It takes more than “red” to be “postbox”, right? — Mww

Yes, objects have many properties. The colour red is a useful example to make a philosophical and linguistic point.

As a side point, it is not the case that objects have properties, but rather objects are a set of properties.

===============================================================================

You name it A, but because neither of us know the cause, I’m perfectly authorized to call that same cause, B — Mww

Yes, I can name it A and you can name it B. However, the point is that an unknown thing, a thing-in-itself, has been named.

==============================================================================

. As soon as it is determinable, it cannot be a thing-in-itself. — Mww

True, but until it has been determined, it is still a thing-in-itself. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI don't see why it has to have caused itself. I think it's commonly known as "reflection". — Metaphysician Undercover

Logically, how can something reflect on itself? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIf we have a reason for choosing something, then those reasons determine our actions....The "choice," between S1 and S2 has to be based on something for us to do any "choosing."...........................so it seems like we can be free in gradations and we are more free when our choices are "more determined by what we want them to be determined by," not when they are "determined by nothing."..................a sort of recursive self-aware self-determination, as opposed to a free floating non-determinism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

As I understand you, I agree that if we were totally free to do whatever we wanted at any moment in time, with no constraints on our actions, we might freely decide not to eat or drink, we might freely decide to jump off a cliff or we might freely decide not to get out of the way of a speeding truck.

But this would be unworkable. Sentient life can only succeed if a limit has been placed on the range of choices available to it within any particular situation. Limits not determined by another mind, but determined by the physical nature of the world. Within limits there is freedom to choose a particular course of action. A certain freedom of choice within a restricted range of possibilities seems an effective evolutionary solution for the development of life.

The question is, what is the nature of this freedom. We feel free to choose between a pre-determined range of available possibilities, but is this freedom in fact an illusion. Is it the case that the range of available possibilities is so restricted that in fact our free will is non-existent.

We are at state S2 and prior to that we were at state S1. Either we are free to choose between moving to future states S3 or S4 or our choice has been pre-determined by state S1.

I can understand the mechanics of Determinism, in that our choice at state S2 has been pre-determined by state S1, but the mechanics of free will elude me, causing me to come to the conclusion that the world is Deterministic and our belief that we have free will is just an illusion.

Suppose free will can cause state S2 to move equally to either S3 of S4, meaning that state S2 can spontaneously and without prior cause move of its own accord equally to either states S3 or S4. This gives us the problem of a spontaneous change in the absence of a prior cause that is not random and somehow determined.

What kind of mechanism can explain a spontaneous change without priori cause that is not random and somehow determined. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismDirect realist: one who attributes properties as belonging to the object itself and which are given to him as such, and by which the object is determined;

Indirect realist: one who attributes properties according to himself, such that the relation between the perception and a series of representations determines the object. — Mww

There are two significant differences between the Indirect and Direct Realist. The Indirect Realist approach is that of metaphysics, whereas the Direct Realist approach is that of Linguistic Idealism.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist see a red post box.

For the Indirect Realist, as we know that the object emits a wavelength of 700nm when we perceive the colour red, the expression "I see a red post box" refers to a perception in the mind and not a material object in the world.

For the Direct Realist, the expression "I see a red post box" is in effect what Wittgenstein would call a hinge proposition, true regardless of what exists in the world. In fact, even if in the world was a pink elephant flying through the sky, the proposition " I see a red post" as a hinge proposition would still be true.

However, both approaches are valid, and each has its own place in our understanding. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIf you see a red postbox, then it is the case the thing comes to you already named, which makes you a direct realist. — Mww

Both the Indirect Realist and Direct Realist see a red postbox.

==============================================================================

If you don’t know the true cause of your representation, how did it get the name red postbox immediately upon you seeing it? — Mww

For the Indirect Realist, the name is of the representation in the mind. For the Direct Realist, the name is of a material object in the world .

===============================================================================

I submit, that when you say you’re seeing a red postbox, it is because you already know what the thing is that you’re perceiving. But there is nothing whatsoever in the perceiving from which knowledge of the perception follows. — Mww

This problem applies to both the Indirect and Direct Realist.

===============================================================================

According to your system, you should be able to name the sound without ever actually perceiving the cause of it. — Mww

True.

===============================================================================

The thing you perceive may indeed end up being named a red postbox, and that for each subsequent perception as well, but the name cannot arise from the mere physiology of your vision — Mww

Very true. Both the Indirect and Direct Realist need things they see to have been named in order to be able to use the name in language.

===============================================================================

Direct realist: one who attributes properties as belonging to the object itself and which are given to him as such, and by which the object is determined;

Indirect realist: one who attributes properties according to himself, such that the relation between the perception and a series of representations determines the object. — Mww

Very true. Even though an object emits a wavelength of 700nm, and we perceive the colour red, the Direct Realist believes that the object is red, whereas the Indirect Realist believes that only their perception of the object is red.

===============================================================================

I submit you don’t see a red postbox. — Mww

Depends on what you mean by the word "see".

===============================================================================

I asked about how the thing-in-itself gets a name — Mww

Suppose we see an affect. We know that if there has been an effect there must have been cause, even if we don't know what the cause was. Let us name the cause A

Suppose we see a broken window. We know that if there has been an effect there must have been cause, even if we don't know what the cause was. Let us name the cause of the broken window A.

IE, we have named something even if we don't know what it is.

===============================================================================

A cause doesn’t have to be known, it just has to be such, for an effect that is itself determinable. — Mww

I agree. If I see a broken window, I know that something has broken it.

We know there has been a cause when we perceive an effect. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismOne can know it by self examination, introspection. It looks like you haven't tried it, or gave up to soon without the required discipline. — Metaphysician Undercover

Is this possible?

Is it possible to have a thought about an internal logical process, when the internal logical process has caused the thought in the first place?

In other words, can an effect cause itself? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI forget if I’ve asked already, but assuming I haven’t……how does a ding as sich have a name?...No. Like….how is it called a cup-in-itself. — Mww

Basically, because we name the unknown cause after the known effect.

As an Indirect Realist, if I see a red postbox, which is a representation in my mind, I name the cause of this representation "a red postbox". I don't need to know the true cause of my representation of a red postbox in order to give this unknown cause a name, ie, "a red postbox".

In ordinary language we say "Clouds of acrid smoke issued from the building". This is a figure of speech for saying that the smell is acrid, not that the smoke in itself is acrid.

In ordinary language we say "Eating sugary or sweet foods can cause a temporary sweet aftertaste in the mouth". This is a figure of speech for saying that the taste is sweet, not that the food in itself is sweet.

It is not the case that we believe that effects have causes, but rather that we know effects have causes. In today's terms, Innatism, and in Kant's terms, the a priori Category of cause.

We know the effect, whether the colour red, an acrid smell or a sweet taste because the effect exists in our minds. We know that effects have prior causes. Therefore we know that there has been a prior cause for our perceptions of the colour red, acrid smell and bitter taste.

It is then a straightforward matter, knowing that there has been a cause, even though we don't know what the cause was, to give this cause a name and name it after the effect.

For example, the unknown cause of our perception of the colour red is named "red", the unknown cause of our perception of an acrid smell is named "acrid" and the unknown cause of our perception of a bitter taste is named "bitter".

The unknown cause of our perceptions is in Kant's terms a thing-in-itself. Even though we don't know what this unknown thing-in-itself is, we can name it. We name it after the effect it has on our perceptions, which is known.

The names "red", "acrid" and "bitter" don't describe unknown things-in-themselves, but in Wittgenstein's terms as he describes in Philosophical Investigations, replace the unknown things-in-themselves.

As regards the cup-in-itself, "cup" names what we perceive in our minds, not something unknown that exists independently of our minds. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismThe point was that people act in ways contrary to their own logical process...The issue is whether people are bound (determined) to act according to what their own logical process dictates. — Metaphysician Undercover

How can we know that. I cannot look at someone and know their internal logical processes. Even I don't know my own internal logical processes. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIn any case, talk of screens and other flat surfaces aside, the original point of contention was the idea that our visual field is a two-dimensional image, and I see nothing whatever to support that assertion. — Janus

You agree that a screen in a flat surface. What is the difference between seeing a portrait of a person in an art gallery and seeing a portrait of a person on a screen. Don't both these appear the same in our visual field, ie, as two-dimensional images? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismBut essentially, the amoeba eventually becomes a man. So maybe it does happen? — Pantagruel

It will happen. The more life evolves the more it will be able to understand. However, although life has been around for over 3.5 billion years, humans still have trouble using a MP3 player, so I don't hold out much hope. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismSo it is "mechanically" possible that there are exactly such unregistered events as Corvus is postulating. — Pantagruel

There are two aspects, being able to perceive something and then being able to make sense of it. Even if a human showed a cat a page from the book "The Old Man and the Sea", it could never make sense of it. Similarly, even if a super-intelligent alien showed us a page from "The True Nature of Reality", we could never make sense of it. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealismthe engineer would sometimes say, all metaphysical knowledge is invalid, because it deals with things that we cannot see or touch — Corvus

Harsh on engineers. The engineer wouldn't say that the physicists knowledge of string theory was invalid because we cannot see or touch one-dimensional objects called strings.

human perception cannot catch every properties of perceptual objects in one single sense data — Corvus

Yes, as regards the apple in front of me, I am unable to perceive the quarks that make it up.

On the next perception, the unperceived properties of the objects might be perceived, and the thing-in-itself gets clearer in its nature. — Corvus

Yes, we now have photographs of individual atoms.

Some thing-in-itself objects are not likely ever to be perceived at all, but we can still feel, intuit or reason about them such as God, human soul and the universe. — Corvus

I don't agree. There is as much a chance of humans being able to feel, intuit or reason about some things-in-themselves as a cat will ever be able to feel, intuit or reason about Western Literature.

As a cat cannot transcend the physical limitations of its brain, neither can a human. -

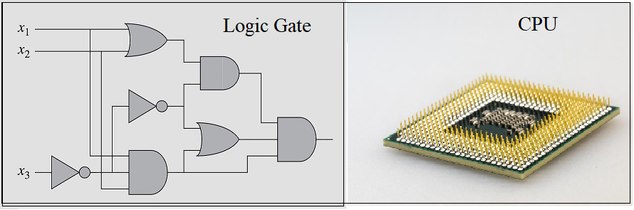

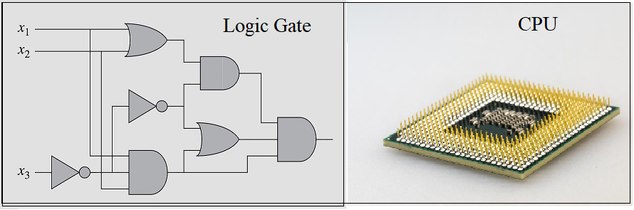

A Case for Transcendental IdealismHuman brain and microchip cannot compare in complexity and also capacity. Same goes with the human mind and computer software. — Corvus

True, but the principles each operates under may be the same. Gravity can attract a ball to the ground and can attract Galaxies together. A difference in complexity but the same principle applies.

===============================================================================

Philosophy can be done in a dark room in vacuum I believe. You go into the room, put on a light, shut the door, take out some of your favorite philosophy books, do some reading, meditating, reasoning, and write what you think about them. — Corvus

True, as long as they have something to think about.

===============================================================================

The most compelling point for Kant's TI are still, whether

1. Metaphysics is possible as a legitimate science or is it just an invalid form of knowledge. — Corvus

A Metaphysician asks "what are numbers". An engineer asks "what does 130 plus 765 add up to". The engineer in designing a bridge doesn't need to know the metaphysical meaning of numbers.

Though different, both the metaphysician's question and the engineer's question are valid, both are legitimate and both are forms of knowledge.

===============================================================================

2. Whether Thing-in-Itself is a true independent existence on its own separate from human cognition therefore unknowable, or whether it is part of human perception, which is possible to be known even if it may look unknowable at first. — Corvus

We as humans know that for every other animal in the world there are some things that are unknown and unknowable to them because of the physical limitations of their brains. For example, we know that a cat can never understand the literary nature of Hemingway's novels.

It would hardly be surprising that as we are also animals, there are some things that are unknown and unknowable to us also because of the physical limitations of our brains. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismDeterminism is not the sort of thing that acts logically any more than Indeterminism...One may logically decide to step out in front of a train. — creativesoul

When we act, is it from Free Will or Determinism. It has been said that we can act illogically because of our free will, inferring that somehow Determinism is logical. This raises the question of what is logic, the subject of numerous Threads, such as the recent thread What is Logic?

My definition of logic is that is that of repeatability, in that given a prior state of affairs A then the subsequent state of affairs B will always happen. It would then be illogical for someone to say that given a prior state of affairs A, then the subsequent state of affairs may or may not be B. Repeatability must be the foundation of logic

For me, Determinism is an exemplar of logic, in that given a prior state of affairs A then the subsequent state of affairs B will always happen. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI'd say the image on the screen like any photo or painting is really a "flat" three-dimensional image — Janus

We could throw caution to the wind and call a "flat" three-dimensional image a two-dimensional image. :smile: -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismAnd, I am pointing out that this type of behaviour, where one acts contrary to one's own logical process, is explained by the concept of free will. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, in practice people commonly act illogically. — Metaphysician Undercover

Free Will may be an illusion

Suppose I saw someone act in an unexpected way. For example, they had bought a winning lottery ticket and then proceeded to tear it up. As an outsider, how can I know their inner logical processes in order to say they are exhibiting either Determinism or Free will.

On the other hand, if I had bought a winning lottery ticket, and freely decided to tear it up, I would think that I was exhibiting Free will. However, what if in fact my act had been determined, and what I thought was Free Will was in fact only the illusion of Free Will.

How can I know that what I think is Free Will is in fact only the illusion of Free Will? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismYou wouldn't call or equate a lump of computer chips and memories as mind, reason or consciousness...Of course the physical existence of the chips and memories are the body where the software defined logic and machine reasoning can be set, and happening. But they are at the software level, not hardware. Software operations are conceptual just like human mind. — Corvus

The brain can be equated with hardware and the mind can be equated with software

I would not equate a computer chip with the mind, but I would equate the computer chip with the brain.

However, there is not a clear distinction between what a thing is and what it does. There is not a clear distinction between what the brain is and what the brain does. There is not a clear distinction between the hardware within a computer and what the software the hardware enables.

A physical structure can only do what the physical structure is capable of doing. A microwave cannot play a DVD, a cat cannot debate the literary values in Ernest Hemingway's novels and the human cannot reason about things that are outwith the physical limitations of its brain.

There are forms such as the brain and hardware in a computer and there are processes, such as the mind in a sentient being and software in a computer. Form and process are distinguished by their relationship with time. The brain and hardware in a computer exists at one moment in time, but the mind and software in a computer need a duration of time in order to be expressed.

That both the mind and computer software require a duration of time to be expressed does not mean that within this duration of time either exist in some form other than physical. IE, when considering one moment in time, neither the mind nor computer software exist outside the physical form of either the brain or computer hardware. The mind and computer software are not some mysterious entities existing abstractly outside of time and space, but rather, exist as the relation between two physical forms at two different moments in time.

As you say that software operations are conceptual, we say that the mind is conceptual, But this does not mean that either the hardware of the computer or brain of the human need to exist outside of time and space in order for the software of the computer or mind of the brain to be expressed.

===============================================================================

Speculative philosophy can be done in a dark room full of vacuum for sure, because its tool is the concepts, logic and reasoning. — Corvus

A philosopher can only philosophise about something

A tool isn't a tool until it is used. A piece of metal at the end of a piece of wood isn't a hammer until it hammers something. As a thought must have intentionality, a thought isn't a thought until it is a thought about something. Similarly, reasoning must be about something. For example, for what reason do apples exist. Tools, concepts logic and reasoning cannot exist if they are not about something, if they don't have some object of investigation.

A Philosopher cannot work in a vacuum. A philosopher cannot philosophise if they have no topic to philosophise about, even if that topic is philosophy itself.

===============================================================================

Plato couldn't talk about Kant obviously, as having not been born for almost another 2000 years, Kant wasn't around when Plato was alive......................Yes, I suppose you could look at any contemporary system or thoughts under the light of Kant's TI, and draw good philosophical criticisms or new theories out of them, and that is what all classical philosophy is about. But as I said, it would be a topic of its own. — Corvus

Kant should be looked at for his philosophy not as a historical figure

True, but as we can compare and contrast Plato and Kant in order to evaluate their respective positions, we can compare and contrast Kant's Transcendental Idealism with contemporary Indirect Realism in order to evaluate their respective similarities and differences.

I think that looking at Kant as a historical figure from the viewpoint of the 18th C may be interesting as a historical exercise, but I don't think it contributes to our philosophical knowledge and understanding. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI would argue that some sort of determinism is a prerequisite for free will. We can't choose to bring about some states of affairs and not others based on our preferences unless our actions have determinant effects. We must be able to predict the consequences of our actions, to understand ourselves as determinant cause. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, there is the problem of how free will can transcend what would otherwise be determined.

1) Imagine two people X and Y at time t with the same physical state of mind A.

2) Suppose person X has no free will. Suppose their physical state of mind at time t + 1 is B

3) Suppose person Y has free will. Suppose their physical state of mind at time t + 1 is C

4) The change in the physical state of mind of person X from A to B has been determined by A

5) The change in the physical state of mind of person Y from A to C cannot have been determined by A, otherwise person Y's physical state of mind would also have changed from A to B.

6) As both person X and Y at time t had the same physical state of mind A, person Y's free will must exist in addition to their physical state of mind.

If free will exists in addition to a person's physical state of mind, and determines changes in a person's physical state of mind, how is free will connected to a person's physical state of mind? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismAnd, I am pointing out that this type of behaviour, where one acts contrary to one's own logical process, is explained by the concept of free will. — Metaphysician Undercover

I see a truck approaching me at speed.

If things were going well in my daily life, the logical thing to do would be to step to one side. This would be an example of Determinism, acting logically.

If things were going well in my daily life, even though the logical thing to do would be to step to one side, out of passion, I decide not to step to one side. This would be an example of Free Will, acting illogically.

In practice, do people act illogically? How many times do we see people in a city centre, when seeing a truck approaching them at speed, decide not to step out of the way?

If there are "forces beyond their control" these are forces not understood, because understanding them allows us to make use of them, therefore control them. — Metaphysician Undercover

The fact that gravity is a force beyond the control of humans does not mean that humans don't understand gravity.

The fact that humans understand gravity does not mean that humans can control gravity. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismThe difference between the physical structure which interprets, what you call the logic gate, and the human mind, is that the human mind does not necessarily have to follow the procedure when the input is applied, while the logic gate does. This is the nature of free will. — Metaphysician Undercover

You're assuming free will rather than determinism.

Why do you think humans have free will rather than being determined by forces beyond their control? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismKant never said a word about the brain in all his works as far as I am aware...Chomsky's Innatism sounds like a type of SocioBiology subject. I am sure it has nothing to do with Kant's transcendental Idealism. Neither Skinner's Behaviourism. — Corvus

True, Kant didn't talk about the brain, but then neither did Plato talk about Kant.

But surely, comparing and contrasting is an important evaluative tool in learning and developing understanding about a topic.

You compared and contrasted Kant with Plato when you wrote:

I thought about Kant as a Platonic dualist too at one point, but as @Wayfarer pointed out, there are clear differences between Kant and Plato.

You also compared and contrasted Kant with knowledge he had and knowledge that only came later, when you wrote:

Anyway, Kant was not a Phenomenologist, and Phenomenology didn't exist when Kant was alive.

I find Kant's Critique of Pure Reason relevant and interesting precisely because it can be explained in today's terms. It is not a dead historical subject, but has insights as to contemporary problems of philosophy.

Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is a battle in the war between Innatism and Behaviourism, as exemplified by Chomsky and Skinner. The a priori and the innate are two aspects of the same thing, the first from a 18th C viewpoint and the second from a 21st C viewpoint.

These we can compare and contrast. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismReason is a way our thoughts work.................Categorical items are not something that operate themselves.................... It is a rational basis for one's action and judgement......................... And of course you can talk about reason as a property of mind just like in CPR. — Corvus

:up:

it sounds like reason is some kind of a biological or living entity itself as a lump of substance. That would be Sci-Fi, not Philosophy...It is a really abstract concept. — Corvus

Where is reason exactly?

As a logic gate is a particular type of structure within a computer, I suggest that reason is also a particular structure within the brain. As the logic gate is a mechanical entity, a lump of substance, similarly, reason is a biological entity, a lump of substance.

As a logic gate has a physical existence, has a concrete existence, the logic gate cannot be said to have an abstract existence. Similarly, as reason has a physical existence, has a concrete existence, reason cannot be said to have an abstract existence .

However, I agree that the thought of a logic gate is an abstract concept, as the thought of reason is an abstract concept. This raises the question as to what are thoughts?

As a CPU within a computer interprets, processes and executes instructions, I suggest that within the brain are also particular types of structures that interpret, process and execute instructions, where a thought is no more than a difference in the physical structure of the brain between two moments in time.

However, if a thought is a difference between two things, can a difference have an ontological existence. For example, there is a difference in height between the Eiffel Tower and Empire States Building of 81metres. In what sense does this difference exist? Either differences do have an ontological existence, in which thoughts ontologically exist, or differences don't have an ontological difference, in which case thoughts don't ontologically exist.

Philosophy cannot be carried out in a vacuum, by a philosopher sitting in a dark room shut off from the world with only their thoughts. The philosopher must take the world into account within their philosophising.

As a logic gate is a mechanical entity, reason is a biological entity. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismOn what basis do you say we initially see a two-dimensional image? I don't, and don't recall ever, seeing a two-dimensional image. — Janus

Depends whether you are using the word "see" metaphorically or literally.

Are you not seeing a two-dimensional image on the screen of your computer/laptop/smartphone at this moment in time as you read these words? -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIn any event, it seems wrong to say that language would be the limit of our world. — Count Timothy von Icarus

:up: -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism'what two-dimensional surface do you think the purportedly two-dimensional image of our visual field is projected onto"? — Janus

When we look at the world, we initially see a two-dimensional image. I am not aware of any two-dimensional surface that this two-dimensional image is projected onto. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismI looked into this further, and it seems to me Kant's Category of Cause is a concept to be applied to the external world events as cause and effect. It is not to do with perceptions or the mental principles of reasoning. I still think the process of reasoning coming to judgements activated by intuitions, perceptions or thoughts is operated by Logic. — Corvus

I am making use of Daniel Bonevac's Video Kant's Categories.

Reason doesn't create logic, rather, what we reason has been determined by the prior logical structure of the brain

The brain must have a physical structure that is logically ordered in order to make logical sense of its experiences of the world. IE, the innate ability of the brain to process such logical functions as quantity, quality, relation and modality. In other words, Kant's Categories, aka The Pure Concepts of the Understanding.

For example, in our terms, Relation includes causality, and Quantity includes the Universal Quantifier ∀ and the Existential Quantifier ∃.

In Kant's terms, there are certain a priori synthetic principles necessary in order to make logical sense of experiences of the world . These innate a priori synthetic principles are prior to Reasoning about the phenomena of experiences through the Sensibilities. It is not the case that our reasoning is logical, rather it is the case that our reasoning has been determined by an innate a priori structure that is inherently logical, one possible consequence of the principle of Enactivism.

Our understanding of the world must be limited by what we are able to know of the world and what we can know of the world is limited by the innate structure of the brain. Taking vision as typifying the five senses, the human eye can detect wavelengths from 380 to 700 nm, which is only about 0.0035% of the total electromagnetic spectrum . In addition, understanding is also limited by the physical structure of the brain. As no amount of patient explanation by a scientist to a cat will enable the cat to understand the nature of quantum mechanics, by analogy, no amount of patient explanation by a super-intelligent alien to a human will enable the human to understand the true nature of quantum mechanics.

Kant is in effect saying that Chomsky's Innatism is a more sensible approach than Skinner's Behaviourism. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismSuperficially true, but insufficient to explain empirical discovery by a solitary subject. — Mww

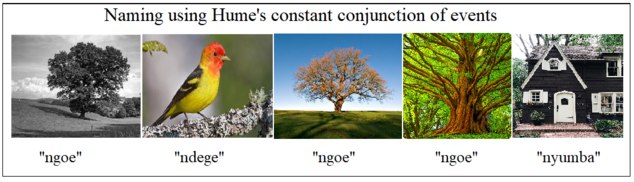

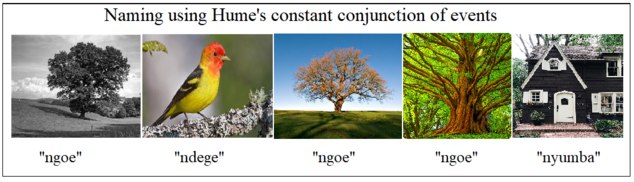

As a solitary subject in a strange land, what would your intuition of the meaning of "ngoe" be ?

.Hume's principle of constant conjunction...............has more to do with the relation of cause and effect than to perception and cognition — Mww

From the IEP article on David Hume: Causation

Whenever we find A, we also find B, and we have a certainty that this conjunction will continue to happen.

If every time I see a particular object and hear someone say "Eiffel Tower", there is a good chance, though not absolute, that the name of this particular object is "The Eiffel Tower".

In a sense, the object does cause someone to say "The Eiffel Tower", in that there is a causal link between the object and the name.

But you just said the name is given by a relevant community, and if “tree” is that name for an object looked upon in the world by yours…..how can it be unique to you? — Mww

The Icelander and Ghanaian can agree with the Communal definition of tree as "a woody perennial plant, typically having a single stem or trunk growing to a considerable height and bearing lateral branches at some distance from the ground".

However, each will have their own unique understanding of what trees are based on their very different lifetime experiences. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismNo. I knew instead what "a thought of a cup" would mean in the context of our discussion. When I think about a cup I'm doing something, but no "thought of a cup" exists. — Ciceronianus

It is only possible for you to write that "but no "thought of a cup" exists" if you already know what the thought of a cup is.

IE, I can only say that that building over there is not the Eiffel Tower if I already know what the Eiffel Tower looks like.

Similarly, you can only say that the thought of a cup doesn't exist if you already know what the thought of a cup is. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIt is never the case we think with language, or by means of it. — Mww

I agree. I have a pain in my left hand whose exact nature is inexpressible in language. The fact that I cannot express in language the exact pain does not mean that there is no pain. As Wittgenstein himself wrote in PI 293 of Philosophical Investigations: "The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all"

We think, and name that which is thought about, the object of thought, cup. — Mww

We look at the world and see an object that has been given a name by the Community within which we live.

Both the object and name are physical things that exist in the world, and we link the object and the name through Hume's principle of constant conjunction.

The name doesn't describe the object, but is linked with the object through Hume's principle of constant conjunction.

IE if every time I saw the Eiffel Tower and at the same time heard the name Eiffel Tower, I would begin associate the name Eiffel Tower with the object Eiffel Tower

As a name is only linked with a thought of an object by Hume's principle of constant conjunction, the one can exist independently of the other. IE, one can have the thought of an object independently of any name it may or may not have been given.

MANY years ago, by sheer accident I put a chainsaw into my left foot. — Mww

Many years ago, I had a garden fork go though my right foot, so I do have an idea of what you experienced.

That every single word ever, and by association every single combination of them into a whole other than the words themselves, being at the time of its instantiation a mere invention, is for that very reason entirely private? — Mww

Yes, for example what I understand by the word "tree" is unique to me, as no one else has had the same life experiences. IE, the meaning of "tree" for an Icelander can only be different to the meaning of "tree" for a Ghanaian. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismIt may do well to note, in addition, as long as we’re “making a case for transcendental idealism”, that since it is merely the thought “cup”, there is already the experience of that particular object by the same subject to which the thought belongs, for otherwise the subject would’ve not had the authority to represent it by name. — Mww

How can a thought be named ?

Is it the case that we have the thought of a cup and then name it, or is Wittgenstein correct

in his belief that we cannot think without language. He wrote in the Tractatus para 5.62: “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

If Wittgenstein is correct, then the mere act of writing "the thought of a cup" presupposes the thought of a cup. -

A Case for Transcendental Idealism2. It is awkward to speak about things-in-themselves; — Bob Ross

"Awkward" in (2) was used somewhat sardonically; "impossible" would presumably be more accurate. — Banno

Wittgenstein in para 293 of Philosophical Investigations makes a strong case that we can speak about things-in-themselves.

He writes:

But suppose the word "beetle" had a use in these people's language?—If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty.—No, one can 'divide through' by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is. That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant.

A word such as "red" does not describe a thing-in-itself, but replaces the thing-in-itself, allowing us to sensibly talk about things-in-themselves.

IE, in Wittgenstein's terms, there is an equivalence between the words "red", as in "I see a red post-box", and "beetle". -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismHave you managed to find Sense and Sensibilia? — Banno

Thanks, I have downloaded a copy and will read it. :up:

===============================================================================

You don't see the cup as having depth? Odd. — Banno

Are you using the word "see" metaphorically?

In my field of vision, I can only see the surface of any object facing me, which appears two-dimensional, but in my mind I can imagine the three-dimensional space the object occupies.

===============================================================================

It's a very odd thing for RussellA to say - even folk with one eye have depth perception. — Banno

I didn't actually say that, but even if I had, I would be in good company.

The BBC Science Focus notes that:

For example, we know the size of things from memory, so if an object looks smaller than expected we know it’s further away. -

A Case for Transcendental IdealismThe atom used to be the stand-in for 'simple' in that it was 'indivisible', not composed of parts. Regrettably, nature did not oblige, as it turns out atoms are far from simple. — Wayfarer

:up:

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum