Comments

-

PerceptionOne colour, or a bundle of colours, can look like another colour. — jkop

Colour is the look, not a wavelength of light (which you seem to be saying here). There is usually a correspondence between the two, but dreams, hallucinations, illusions, and cases such as the dress show that this correspondence doesn't always hold.

The blind can't see anything no matter what their brains are doing. — jkop

See cortical visual prostheses. -

PerceptionThey're both elements for the emergence of red experience(s). — creativesoul

Although re-reading this, maybe I've misunderstood you. Are you saying that these are three distinct things?

1. 650-720nm light

2. The colour red

3. Red experiences -

PerceptionThey're both elements for the emergence of red experience(s). — creativesoul

Sure, like getting stabbed or burnt or whatever are elements for the emergence of pain experience(s). But pain is nonetheless the experience. My claim is only that these colour experiences are our ordinary and everyday understanding of colours. When I think about the colour red I'm not thinking about atoms and electrons and photons or anything like that; I'm thinking about the experience. -

PerceptionUnless having already seen red is necessary for the illusion to work. — creativesoul

By this do you mean that 620-750nm light must have stimulated my eyes for me to see the colour red? Why do you think that? What’s the relationship between 650-720nm light and the colour red? -

PerceptionThe arguments from illusion continue to pile up, as if the hight of the pile would make them more convincing. :roll: — jkop

Well, whether you’re convinced by it is irrelevant. What matters is that both a) I see a can of red Coke and b) the photo does not emit 620-750nm light are true. So one’s account of seeing the colour red cannot depend on 620-750nm light.

The factual explanation is that the colours we see are determined by what the brain is doing. -

PerceptionYep, is “color in a perceiver”? Well, sure if you open the skull to see the brain, it may appear grayish. But I suspect they are saying something rather metaphysical here, unverifiable. — Richard B

No, what they're saying is that the subject sees colours when there is activity in the V4 and VO1 areas of the visual cortex. Normally these areas are active in response to retinal stimulation by light, but that's incidental to seeing colours. -

PerceptionWith regards to “grammatical fiction”, this is one of Wittgenstein ideas he expressed in PI 307,

“Are you not really a behaviorist in disguise? Aren’t you at the bottom really saying that everything except human behavior is a fiction?” - If I do speak of a fiction, then it is of a grammatical fiction.” — Richard B

And what does that have to do with anything I have said here, in particular that comment that you replied to? I am simply reporting that "the major physicists who have thought about color ... hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess" and that Maxwell has said "colour is a sensation".

Are you saying that Maxwell and most major physicists are wrong? Are you suggesting that somehow Wittgenstein's analysis of language can tell us about the physics of tomatoes and the physiology of visual experience, including colour experience?

Science studies stuff like brains, nerves, cells, molecules, etc… Not sensations and mental percepts. — Richard B

Neural representations of perceptual color experience in the human ventral visual pathway

There is no color in light. Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus. This distinction is critical for understanding neural representations, which must transition from a representation of a physical retinal image to a mental construct for what we see. Here, we dissociated the physical stimulus from the color seen by using an approach that causes changes in color without altering the light stimulus. We found a transition from a neural representation for retinal light stimulation, in early stages of the visual pathway (V1 and V2), to a representation corresponding to the color experienced at higher levels (V4 and VO1). -

PerceptionHe's said there's no colored things aside from mental percepts. — creativesoul

Not quite. I'm saying that colour and pain are percepts. We can still talk about tomatoes being colourful and stubbing one's toe being painful; we just have to interpret such talk according to something like dispositionalism, whereas you seem to be interpreting tomatoes being colourful according to something like naive realism, and it this naive realist interpretation that the science has disproven.

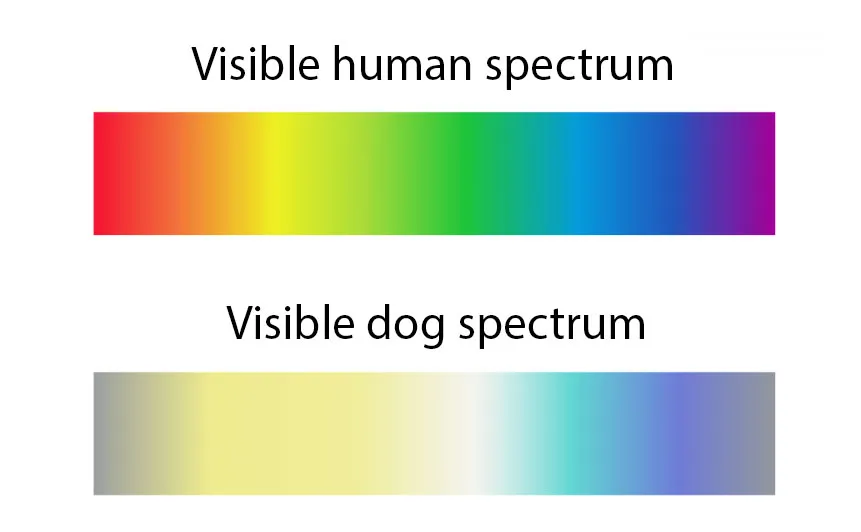

It is not the case that colour is a property of tomatoes but only that tomatoes have a surface that reflects ~700nm light, and this light happens to cause red percepts in most humans, with different organisms possibly having different colour percepts in response to that same light, e.g. see the difference between the visible spectrum for humans and dogs, or even the dress that some see to be white and gold and others as black and blue. -

PerceptionFeel free to keep your grammatical fiction, it may serve you well. — Richard B

I don't know what you're talking about. This has nothing to do grammar. This has to do with physics and physiology. Maxwell knew better than you about how the world works, especially when it comes to light. As he says, colour is a sensation. -

PerceptionWe see our color percepts?

Yup. There's the Cartesian theatre. Homunculus lives on... — creativesoul

Feeling pain does not entail a "Cartesian theatre" or a homunculus, even though pain is a sensation, and seeing colours does not entail a "Cartesian theatre" or a homunculus, even though colour is a sensation.

You're arguing against a strawman. -

PerceptionI would say Michael, and others, are committed to a particular metaphysical worldview I like to call “The Private Theater.” — Richard B

I'm not committed to any metaphysics. I'm only committed to physics, and as the SEP article on colour explains, "the major physicists who have thought about color ... hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess", which is why such luminaries as James Clerk Maxwell, the scientist who first developed the theory of light as electromagnetism, said "colour is a sensation".

That's it. You are reading something into my words that just isn't there. -

PerceptionWhen Michael says that colors are percepts or that we only ever see percepts and never colors, he is in a very real sense committing himself to the position that we only ever see colors indirectly. — Leontiskos

We see colours "directly", just as we feel pain "directly". -

PerceptionThere's that vicious circularity again. — Banno

It's not circular, just as noting that the predicate "is painful" is used to describe things which cause pain mental percepts is not circular.

The fact that we say "is red" rather than something like "is redful" seems to have you confused.

"It seems to me that the philosophy of color is one of those genial areas of inquiry in which the main competing positions are each in their own way perfectly true."

Naive colour realism certainly isn't true. Even the paper you quoted seems to agree with that:

The dispositionalist should not be disturbed by the fact that this admission is at odds with a naive conception of color, i.e., a conception which conforms to Revelation and as a result thinks of surfaces as wrapped in phenomenally revealed features which will always make it a determinate fact what the real color of the surface is. (For we have shown that such a conception is not coherent, not consistent with the idea that we see colors.)

The science is clear that with respect to these phenomenal qualities, eliminativism and subjectivism are correct. -

PerceptionIf there is no color in the world, then rainbows and visible spectrums are colorless.

I'm not okay with that, because rainbows and visible spectrums are colorful. — creativesoul

That's just begging the question.

Rainbows are just refracted light, with longer wavelengths at the top and shorter wavelengths at the bottom. It's an incidental fact about human physiology that retinal stimulation by light causes colour experiences, with different wavelengths being responsible for different colours.

That's why Newton said "For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured" and why Maxwell said "colour is a sensation". You might not be "okay" with this, but them's the facts.

And here's an image that you might find enlightening:

-

PerceptionNo, I'm not looking for a term, and plaster walls are not fluorescent.. — jkop

But plaster walls don't emit (visible) photons, which is why I can't see them at night when I close the curtains and turn off the light. Like most other things they just reflect the (visible) light from some other source. -

Perception

I think the term you're looking for is "fluorescent", not "pigmented". If we're talking about the powder, conventional pigments don't emit light (although there is such a thing as fluorescent pigments).

Not sure how any of this is relevant to the topic though. -

PerceptionYet I don't know of any good arguments against nsive realism, so perhaps it's worth investigating — jkop

There are no arguments against naive realism; there is experimental evidence against it. Physics and neuroscience disproved it a long time ago. -

Perception

-

PerceptionI guess that having been informed about the relevant science for a long time, it's rather baffling to me that so much energy is going into such a philosophical discussion. — wonderer1

It baffles me that people still think it's a matter for philosophy, as if we can use a priori reasoning to figure out the nature of sensory experiences and their relationship to distal objects. It's even more baffling that some think that this can be determined by an examination of language.

And perhaps most baffling of all is those who accuse me of misrepresenting the science, as if Maxwell literally saying "colour is a sensation" is not the father of electromagnetism literally saying that colour is a sensation. -

PerceptionIt is an arbitrary fact about English that the adjectives are "red" and "painful" rather than "redful" and "pain". If language had developed differently then we would say such things as "the tomato is redful" and "stubbing one's toe is pain". I'd still be arguing that pain is a mental phenomenon, either reducible to or caused by neural activity in the brain. And then you'd retort with the non sequitur "nuh, 'cause we all agree that stubbing one's toe is pain", showing your utter confusion brought on by equivocation and an absurd obsession with language.

The science has shown that naive colour realism is wrong and that eliminativism and subjectivism are right. Projectivism explains why we are initially naive colour realists, and dispositionalism provides a reasonable post hoc description of how we use such predicates as "is red". -

PerceptionHe continues, "First, for something to be red in the ontologically objective world is for it to be capable of causing ontologically subjective visual experiences like this..." — Richard B

Yes, that's what I said in that previous post:

"the predicate 'is red' is used to describe objects which cause red mental phenomena."

But our ordinary, everyday conception of colours is that of the ontologically subjective visual experience, not a material surface of electrons absorbing and emitting various wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation.

This is how we can make sense of such things as the inverted spectrum, or different people seeing a different coloured dress when looking at the same photo emitting the same light. -

PerceptionIt's odd that Michael sees Searle as a friend, when Searle has spent so much effort in showing the intentional character of perception. — Banno

This has nothing to do with intentionality. This has to do with colours. -

Perception

Neural representations of perceptual color experience in the human ventral visual pathway

There is no color in light. Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus. This distinction is critical for understanding neural representations, which must transition from a representation of a physical retinal image to a mental construct for what we see. Here, we dissociated the physical stimulus from the color seen by using an approach that causes changes in color without altering the light stimulus. We found a transition from a neural representation for retinal light stimulation, in early stages of the visual pathway (V1 and V2), to a representation corresponding to the color experienced at higher levels (V4 and VO1). The distinction between these two different neural representations advances our understanding of visual neural coding. -

PerceptionHowever the light source being reflected off of the tomato and into the eyes is no less a relevant part of the scientifc understanding of what is happening. — wonderer1

Of course it's relevant, but it's not colour. Just as stubbing one's toe is relevant to explain pain, but isn't itself pain. Pain and colour are what happen in the head after. -

PerceptionNothing he says aligns with the mistake your entire philosophical edifice, informed stance, rests its laurels upon. See the top of this post. — creativesoul

My "stance" is repeating what those more knowledgeable of the matter have said:

Maund: "It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess."

Newton: "For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour."

Kim et al: "Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus."

Palmer: "Color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights."

Maxwell: "Color is a sensation." -

PerceptionSir. You most certainly did.

You drew a hard fast equivalency between four different things. When I asked you what the differences were between them the answer was the same.

"Nothing"

That is most certainly to claim that there are no differences!

Fer fuck's sake! — creativesoul

You asked me for the difference between an hallucinated red and a red percept. There is no difference because an hallucinated red is a red percept. I didn't say that there's no difference between seeing a red pen and hallucinating a red pen.

You should try reading more carefully. -

PerceptionBut perhaps the generic form of the mistake is in thinking that there can be one explanation that will work for all the many and various ways in which we might use colour words. — Banno

And this is the mistake that you are forever making. This has nothing to do with the various ways in which we might use colour words. This has nothing to do with language at all. This is about vision and whether or not its qualities are mind-independent properties of tomatoes. We naively think they are, but physics and neuroscience has shown that they're not.

The fact that the word "blue" is sometimes used to mean that someone is sad or that the word "green" is sometimes used to mean that someone is inexperienced simply has no relevance at all to the discussion. -

PerceptionIt does not follow that there are no differences between hallucinating, dreaming, and seeing red things. — creativesoul

I haven't claimed that there is no difference. We've been over this. They differ in what causes the mental percept.

No, it's not. — creativesoul

Yes, it is. See all the quotes here.

Maund: "It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess."

Newton: "For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour."

Kim et al: "Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus."

Palmer: "Color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights."

Maxwell: "Color is a sensation."

How much more explicit does this need to be for you? -

Perception“When a mental occurrence can be regarded as an appearance of an object external to the brain, however irregular, or even as a confused appearance of several such objects, then we may regard it as having for its stimulus the object or objects in question, or their appearances at the sense-organ concerned. When, on the other hand, a mental occurrence has not sufficient connection with objects external to the brain to be regarded as an appearance of such objects, then its physical causation (if any) will have to be sought in the brain. In the former case it can “be called a perception; in the latter it cannot be so called. But the distinction is one of degree, not of kind. Until this is realized, no satisfactory theory of perception, sensation, or imagination is possible.” — Richard B

Whether you call it "perception" or not is irrelevant. Call it "blugh" for all it matters. The only thing that is relevant is that the visual quality that we naively think of as being a mind-independent property of a tomato's surface is in fact a mental phenomenon either reducible to or caused by neural activity in the brain, usually in response to optical stimulation by light. This is what the science shows, and no appeals to grammar or beetles in boxes or anything of the sort can prove otherwise. -

PerceptionThe point of this example is to show that Russell is concerned about the grammar of colour, so we can get it right about what science is actually investigating. — Richard B

The topic is about perception, not grammar. Science explains perception. This has nothing to do with language at all. We can imagine that we're deaf, illiterate, mutes if it helps you move on from this distraction. We still see colours. I don't need to be able to say "this box looks red" and "this box looks blue" for me to see a visual difference between them. The development of the words "red" and "blue" to name the difference comes after the fact, not before. -

Perceptioncolours are systematic hallucinations — jkop

And hallucinations are what? A type of mental phenomenon, not a mind-independent property of tomatoes. Therefore colours are a type of mental phenomenon, not a mind-independent property of tomatoes.

you're having experiences without experiencing anything — jkop

This is such a nonsensical sentence. -

Perception

Russell is not saying what (I think) you think he's saying. When he says "the sensation that we have when we see a patch of colour simply is that patch of colour" he is saying that colour just is that sensation. This is perhaps clearer in a later work where he says this:

Scientific scripture, in its most canonical form, is embodied in physics (including physiology). Physics assures us that the occurrences which we call ''perceiving objects'' are at the end of a long causal chain which starts from the objects, and are not likely to resemble the objects except, at best, in certain very abstract ways. We all start from "naive realism', i.e., the doctrine that things are what they seem. We think that grass is green, that stones are hard, and that snow is cold. But physics assures us that the greenness of grass, the hardness of stones, and the coldness of snow, are not the greenness, hardness, and coldness that we know in our own experience, but something very different. The observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself. Thus science seems to be at war with itself; when it most means to be objective, it finds itself plunged into subjectivity against its will. Naive realism leads to physics, and physics, if true, shows that naive realism is false. Therefore naive realism, if true, is false; therefore it is false.

I don't have a copy of Searle, but according to this:

Searle presents the example of the color red: for an object to be red, it must be capable of causing subjective experiences of red. At the same time, a person with spectrum inversion might see this object as green, and so unless there is one objectively correct way of seeing (which is largely in doubt), then the object is also green in the sense that it is capable, in certain cases, of causing a perceiver to experience a green object.

This seems to be arguing that colours are mental phenomena and that the predicate "is red" is used to describe objects which cause red mental phenomena.

On colour, Quine has said this:

But color is cosmically secondary. Even slight differences in sensory mechanisms from species to species, Smart remarks, can make overwhelming differences in the grouping of things by color. Color is king in our innate quality space, but undistinguished in cosmic circles. Cosmically, colors would not qualify as kinds.

Your quote of him is him arguing for eliminative materialism, which I have previously accepted is a possibly correct account of so-called mental phenomena (e.g. pain just is a type of brain activity, and so colours just are a type of brain activity). -

PerceptionI've no idea how you arrive at the notion that color is nothing but a mental percept — creativesoul

It's not my conclusion; it's what the science says, and I am simply reporting on that. I have no idea why you and others think that you can figure out how perception works by sitting in your chair and thinking really hard. -

PerceptionIt's you who are claiming that the tomato is red but not really red; these are your words — Banno

They're not my words. I said that the tomato does not have the property that it appears to have. The property that it appears to have is in fact a subjective quality, and so is a percept, not a mind-independent property of material surfaces.

You are showing yet again that you are equivocating. As you have mentioned before, the predicate "is red" doesn't just mean one thing. What the dispositionalist means by "the tomato is red" isn't what the naive colour realist means by "the tomato is red". According to the former meaning, "the tomato is red" is true. According to latter meaning, "the tomato is red" is false.

My concern isn't with the sentence "the tomato is red" precisely because the sentence is used to mean different things by different people (and you haven't explained what you mean by it); my concern is with the nature of a tomato's appearance. This is explained by physics and physiology, not by language, and eliminativism is consistent with the science (with projectivism explaining the way we think and talk about colours). -

PerceptionI have seen you do little more in this thread than make arguments from authority. — Leontiskos

Yes. Perception cannot be explained by armchair philosophy. It can only be explained by physics and physiology, and so I am simply reporting on what the scientists have determined. I'll do so again:

Vision science: Photons to phenomenology:

People universally believe that objects look colored because they are colored, just as we experience them. The sky looks blue because it is blue, grass looks green because it is green, and blood looks red because it is red. As surprising as it may seem, these beliefs are fundamentally mistaken. Neither objects nor lights are actually “colored” in anything like the way we experience them. Rather, color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights. The colors we see are based on physical properties of objects and lights that cause us to see them as colored, to be sure, but these physical properties are different in important ways from the colors we perceive.

Color:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess. Oceans and skies are not blue in the way that we naively think, nor are apples red (nor green). Colors of that kind, it is believed, have no place in the physical account of the world that has developed from the sixteenth century to this century.

Not only does the scientific mainstream tradition conflict with the common-sense understanding of color in this way, but as well, the scientific tradition contains a very counter-intuitive conception of color. There is, to illustrate, the celebrated remark by David Hume:

"Sounds, colors, heat and cold, according to modern philosophy are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind." (Hume 1738: Bk III, part I, Sect. 1 [1911: 177]; Bk I, IV, IV [1911: 216])

Physicists who have subscribed to this doctrine include the luminaries: Galileo, Boyle, Descartes, Newton, Thomas Young, Maxwell and Hermann von Helmholtz. Maxwell, for example, wrote:

"It seems almost a truism to say that color is a sensation; and yet Young, by honestly recognizing this elementary truth, established the first consistent theory of color." (Maxwell 1871: 13 [1970: 75])

This combination of eliminativism—the view that physical objects do not have colors, at least in a crucial sense—and subjectivism—the view that color is a subjective quality—is not merely of historical interest. It is held by many contemporary experts and authorities on color, e.g., Zeki 1983, Land 1983, and Kuehni 1997.

Neural representations of perceptual color experience in the human ventral visual pathway:

There is no color in light. Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus. This distinction is critical for understanding neural representations, which must transition from a representation of a physical retinal image to a mental construct for what we see. Here, we dissociated the physical stimulus from the color seen by using an approach that causes changes in color without altering the light stimulus. We found a transition from a neural representation for retinal light stimulation, in early stages of the visual pathway (V1 and V2), to a representation corresponding to the color experienced at higher levels (V4 and VO1).

Opticks:

The homogeneal Light and Rays which appear red, or rather make Objects appear so, I call Rubrifick or Red-making; those which make Objects appear yellow, green, blue, and violet, I call Yellow-making, Green-making, Blue-making, Violet-making, and so of the rest. And if at any time I speak of Light and Rays as coloured or endued with Colours, I would be understood to speak not philosophically and properly, but grossly, and accordingly to such Conceptions as vulgar People in seeing all these Experiments would be apt to frame. For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour.

They are literally saying "color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights", "color is a sensation", "color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus", and "For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour."

I cannot be misrepresenting them by quoting their own words. They mean exactly what they say.

Your only retort seems to be that we talk about colours as if they are properties of pens. And yes, we often do. And we're wrong, as the science shows. -

PerceptionWhen we speak about the pen we are speaking about the pen, not about percepts. Pens and percepts are two different things. Maybe you (erroneously) think everyone should replace all of their color predications about pens with predications about percepts, but this in no way shows that when people talk about red pens they are doing nothing more than talking about percepts. — Leontiskos

Yes, and that's the fallacy. See the SEP article on color:

On a third view, Color Projectivism, the qualities presented in visual experiences are subjective qualities, which are “projected” on to material objects: the experiences represent material objects as having the subjective qualities. Those qualities are taken by the perceiver to be qualities instantiated on the surfaces of material objects—the perceiver does not ordinarily think of them as subjective qualities.

This is what we naively do, and physics and neuroscience has proven it false. When you talk about red pens you are talking about both pens and percepts, whether you realise it or not. -

Perception

That the pen is red just is that it (ordinarily) appears red, and the word “red” in the phrase “appears red” does not refer to a mind-independent property of the pen but to the mental percept that looking at the pen (ordinarily) causes to occur. -

Perception

I don't care about how Wittgenstein viewed perception and colours. He was not a physicist or a neuroscientist and so he didn't have the appropriate expertise. To think that somehow an examination of language can address such issues is laughable. Do you want to do away with the Large Hadron Collider and simply talk our way into determining how the world works? -

Perception

You need to get over your obsession with language. The discussion is about perception, not speech. We must look to physics and physiology, not to all the ways that the word “red” is used in English.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum