Comments

-

PhenomenalismLets look at another example typically given to say that we are only sure or our sense data but not the thing-in-itself. Take a table in the middle of the room, we look at it and say the color is brown. However, it we get real close to it it seems to be grayish brown, and the time a day changes and lighting of the rooms changes the table looks reddish. Is it reasonable to then conclude, “see, this proves that we can never know the actual/the real color of the table, the thing-in-itself.” — Richard B

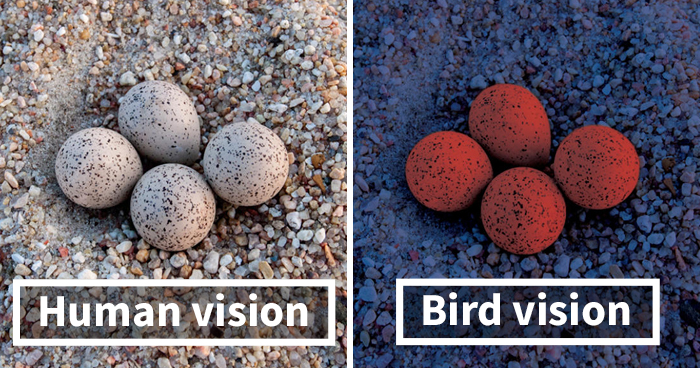

I think that our understanding of visual perception, of electromagnetic radiation, of electrons absorbing and scattering photons, etc. shows that it's a category error to talk of external world objects as having a colour-property. Take for example this photo:

It's not the case that either humans or birds (or both) are seeing the wrong colour. It's just the case that humans and birds have a different brain and eye structure, and so different sense data is triggered by the same stimulus. -

PhenomenalismSo science has access to the properties of mind independent objects? How is this possible if those properties are not present in experience? — Tate

I'm not a scientist, I don't know how it works (I've only read about the results), but I presume scientists don't actually see subatomic particles. -

PhenomenalismThat's phenomenalism as I understand it. I guess my question would be: what supports this claim? — Tate

Please explain what direct access means. What is an example of having direct access? If we want to confirm “Yes, we have direct access” don't we need some idea what that would be like when it is achieved? — Richard B

I think the section on The Character of Experience here gives a simple explanation: "the phenomenal character of experience is determined, at least partly, by the direct presentation of ordinary [mind-independent] objects."

What I understand this to mean is that if experience is direct and if I see something as white then that thing has that property of whiteness (as seen).

This is consistent with the motive of the direct and indirect realists to answer the epistemological problem of perception: does perception provide us with information about the nature of the mind-independent world?

As such, to answer Tate's question, Art48's assertion that we don't have direct access to the external world would be supported by showing either that a) the properties of mind-independent objects are not present in the experience or that b) the phenomenal character of experience is not a property of mind-independent objects.

I think that our scientific understanding of perception shows that both a) and b) are true. Pain and colour are not properties of mind-independent objects, and a mind-independent object being a collection of subatomic particles that absorb and/or reflect electromagnetic radiation isn't present in the experience. -

Is there an external material world ?In other words. We do not 'see' qualia. They are (in the paper) an inferred part of our internal model of how perception works. — Isaac

Even if they don't say that we see qualia, the point still stands that colour terms like "red" (can) refer to this qualia, which according to them is a Bayesian model, and so colour terms like "red" don't (only) refer to some property of the external cause of the sensation.

The mistake you seem to be making is to conflate our external world model with the external world. But as they say, "despite holding all the phenomenal facts fixed, how the world really is might vary, even to the point of there being nothing at all bearing the properties so confidently represented as being present" which only makes sense if "the properties so confidently represented as being present" refers to something. And that something is "in the head". This is the sort of thing that colour terms like "red" refer to, even with this Bayesian interpretation of perception, and any further claim of this kind of redness being a property of some external cause of perception is a naive projection.

There is, perhaps undoubtably, some external world property of things that causes most humans to see red (i.e. infer these Bayesian models), but that model (and its properties) isn't that external world thing (or its properties). You can use the same word to refer to both if you want, but as I have said, and as you seem to be demonstrating, that leaves us susceptible to equivocation, and the erroneous claim that there is a "right" way to see things like colour. A human isn't wrong if he sees colours as birds do; his visual system is just atypical of humans. -

PhenomenalismI am directly experiencing you looking at a tree, I don’t directly experience your sense data of a tree. — Richard B

Looking at something and seeing something are not the same thing. He might be blind. -

Is there an external material world ?@Isaac

Sentience and the Origins of Consciousness: From Cartesian Duality to Markovian Monism

The primary target of this paper is sentience. Our use of the word “sentience” here is in the sense of “responsive to sensory impressions”. It is not used in the philosophy of mind sense; namely, the capacity to perceive or experience subjectively, i.e., phenomenal consciousness, or having ‘qualia’. Sentience here, simply implies the existence of a non-empty subset of systemic states; namely, sensory states. In virtue of the conditional dependencies that define this subset (i.e., the Markov blanket partition), the internal states are necessarily ‘responsive to’ sensory states and thus the dictionary definition is fulfilled. The deeper philosophical issue of sentience speaks to the hard problem of tying down quantitative experience or subjective experience within the information geometry afforded by the Markov blanket construction.

Regarding the "hard problem" it does refer to this paper:

Bayesing Qualia: Consciousness as Inference, not Raw Datum

The meta-problem of consciousness (Chalmers (this issue)) is the problem of explaining the behaviors and verbal reports that we associate with the so-called ‘hard problem of consciousness’. These may include reports of puzzlement, of the attractiveness of dualism, of explanatory gaps, and the like. We present and defend a solution to the meta-problem. Our solution takes as its starting point the emerging picture of the brain as a hierarchical inference engine. We show why such a device, operating under familiar forms of adaptive pressure, may come to represent some of its mid-level inferences as especially certain. These mid-level states confidently re-code raw sensory stimulation in ways that (they are able to realize) fall short of fully determining how properties and states of affairs are arranged in the distal world. This drives a wedge between experience and the world.

...

Qualia – just like dogs and cats – are part of the inferred suite of hidden causes (i.e., experiential hypotheses) that best explain and predict the evolving flux of energies across our sensory surfaces.

...

Schwarz’ imaginary foundations are purpose-built to fill that role. They are purpose-built to be known with great certainty, while not themselves being made true simply by states of the distal world. Creatures thus equipped would be able, were they sufficiently intelligent, to assert that despite holding all the phenomenal facts fixed, how the world really is might vary, even to the point of there being nothing at all bearing the properties so confidently represented as being present.

...

We suggest that ‘imaginary foundations’, far from being a highly speculative addition to standard accounts of hierarchical Bayesian inference, are in fact a direct consequence of them. They arise when mid-level re-coding of impinging energies are estimated as highly certain, in ways that leave room for the same mid-level encodings to be paired with different higher-level pictures, including ones in which nothing in the world corresponds to the properties and features at all (as we might judge in the lucid dreaming case).

...

That puzzlement finds its fullest expression in the literature concerning the ‘explanatory gap’, where we are almost fooled into believing that there’s something special about qualia – that they are not simply highly certain midlevel encodings optimized to control adaptive action.

...

From the PP perspective, [qualia] are just more predictively potent mid-level latent variables in our best generative model of our own embodied exchanges with the world. They are not some kind of raw datum on which to predicate inferences about the state of body and world. Rather, they are themselves among the many products of such inference.

...

But in another sense, this is a way of being a revisionary kind of qualia realist, since colors, sights, and sounds are revealed as generative model posits pretty much on a par with representations of dogs, cats, and vicars.

...

Our distinctive capacities for puzzlement then arise because, courtesy of the depth and complexity of our generative model, we are able to see that these groupings (the redness of the objects, the cuteness of some animals) reflect highly certain information that nonetheless fails to fully mandate specific ways for the external world (or body) to be. We thus become aware that these states, known with great certainty, seem to belong to the ‘appearance’ side of an appearance/reality divide (see Allen (1997)).

...

It is realist in that it identifies qualia with distinctive mid-level sensory states known with high systemic (and 100% agentive) certainty.

...

Our own qualitative experiences, this suggests, are not some kind of raw datum but are themselves the product of an unconscious (Bayesian) inference, reflecting the genuine (but entirely non-mysterious) combination of processes described above.

So, 1) the science of Markov blankets doesn't directly address the philosophical issue of subjective experience (as explained in the first paper) and 2) colour terms like "red" don't (only) refer to some property held by some external world cause but (also) by something that happens "in the head" (even if you want to reduce qualia/first-person experiences to be something of the sort described in the second paper). -

Is there an external material world ?I don't see how we 'know' this. Certainly not scientifically. All the data we have scientifically seems to show that experiences cannot be said to have properties such as colours. There simply isn't the mechanism.

So do we 'know' it phenomenologically? Again, I don't see how. All we have phenomenologically is that I seem to think the dress is blue and you seem to think its red. There's nothing in my experience which tells me why. — Isaac

Do you say the same about being fun, good, scary, painful? You don't understand how these words refer to some feature of the experience and not (just) the external stimulus? -

PhenomenalismPutnam’s goal in introducing the vatted brain was to refute the skeptical argument. — Banno

The interesting thing about Putnam's argument is that it's about meaning, not about ontology, and depends on a causal theory of reference. I think it strange that in such a scenario the brain-in-a-vat cannot refer to itself as being a brain in a vat, and so I think that Putnam's argument is actually a reductio ad absurdum against a causal theory of reference. -

Is there an external material world ?One such is the idea that there's some internal'redness' which we directly experience. There's no mechanism for such a thing, and what mechanisms we can see suggest it isn't happening. — Isaac

What we know is that if I see a red dress and you see a blue dress then our first-person experiences are different, and that the colour terms "red" and "blue" refer to whatever it is that differs in our experiences.

If we don't yet have a scientific explanation of this mechanism then that simply shows that our scientific explanations are inadequate. Which most people accept is true, given that the hard problem of consciousness hasn't been solved. -

Is there an external material world ?Because that's the consequence of what we know about how brains work. — Isaac

Again, allowing some aspects of neuroscience to inform your understanding but denying others — Isaac

Neurology doesn't explain the hard problem of consciousness. We know that changes to the eyes and changes to the brain affect first-person experience, but we haven't reduced first-person experience to brain- or body-activity. And even if we do reduce first-person experience to brain- or body-activity, it can still be that colour terms like "red" refer to some property of this brain- or body-activity, not just to some property of the external stimulus.

Why is it that when electromagnetic waveforms impinge on a retina and are discriminated and categorized by a visual system, this discrimination and categorization is experienced as a sensation of vivid red? We know that conscious experience does arise when these functions are performed, but the very fact that it arises is the central mystery. There is an explanatory gap (a term due to Levine, 1983) between the functions and experience, and we need an explanatory bridge to cross it. A mere account of the functions stays on one side of the gap, so the materials for the bridge must be found elsewhere. — Chalmers, 1995

How do we know that? How have we updated our model of what's happening in tetrachromats?

By following the evidence from neuroscience. By accommodating what we've discovered about how brains work into our understanding of perception.

Again, allowing some aspects of neuroscience to inform your understanding but denying others — Isaac

If most people are scared of spiders it doesn't follow that the minority who aren't scared of spiders are wrong. I don't see how understanding the human brain has any relevance to this fact. -

Is there an external material world ?We do appear to see most colours the same so someone must be wring about the dress. — Isaac

And this definitely doesn't follow. Most humans are trichromats. The very rare tetrachromats aren't wrong in seeing different colours to the rest of us. -

Is there an external material world ?If it's relevant then you have to accept that you don't 'really' experience red either, it's just a post hoc narrative constructed by your working memory. — Isaac

I don't see how that follows. -

Is there an external material world ?What we call that intrinsic property seems to be the sticking point. — Isaac

I don't think that's quite right. I've accepted that we can use words like "red" to refer to that intrinsic property. The disagreement is that I also think we can (and do) use words like "red" to refer to the effect, i.e. some quality of the experience. The reason I "reach" for the colour terms "white" and "gold" is because those are the words that refer to the quality of my experience. So an intrinsic property is red1 if it causes most humans to experience red2. But there are some who might experience blue2 because their eyes and/or brain work differently. -

Is there an external material world ?You seeing white and gold dress and me seeing a black and blue is not remotely random — Isaac

I'm not saying it's random. I'm saying that it's wrong to say that they "match". The external property may determinately cause the experience, but they are distinct things. A broken window isn't a property of the ball. -

Is there an external material world ?I just don't see a problem with calling that property 'being scary'. — Isaac

It's not a problem in ordinary conversation. It can be a problem if it leads you to the philosophical position that being scary is a mind-independent property that some people are "correct" in experiencing and others "mistaken" in not. -

Is there an external material world ?Unless it is doing so randomly, then there has to be a match between property and experience? — Isaac

The fact that you and I can look at the same photo and yet I see a white and gold dress and you see a black and blue dress proves this wrong. The external properties are the same and yet the internal qualities are different. The experience is determined by our eyes and brain as well as any external stimulus. The mistake is in then projecting the qualities of the experience onto the external stimulus. -

Is there an external material world ?But we clearly aren't referring to the properties of the experience. When I say "the post box is red" I'm clearly referring to the post box. The grammar could not be more clear. — Isaac

I think this is where we might be talking past each other. When I play a computer game I might say that the game is good or is fun or is scary or whatever, and the grammar is clearly referring to the computer game and saying that it has certain properties. And that's fine for everyday conversation. But being good, being fun, being scary, and so on are not external properties of things that are then "encountered". They refer to my state of mind (emotional rather than sensory in this case). You might also want to use the words "good", "fun", and "scary" to refer to some external property that causes us to feel these things, but I would say that that is secondary to the primary meaning.

I think most people would agree with me at least on this. I just think it's correct to extend this understanding to sensory qualities like colour and shape. -

Is there an external material world ?This is the move I don't understand. On what grounds 'trivial'? — Isaac

Given that we see what we see then it follows that the external world is such that it causes us to see what we see. In terms of the epistemological problem of perception it's trivial. What we're interested in is whether or not the external world, when not seen or felt, "resembles" the world as-seen and as-felt. Do our everyday experiences show us the "intrinsic" nature of this external world? Are the shapes and colours and sounds that we're familiar with properties of the external world or just qualities of the experience? How much of what we see and feel is a product of us and our involvement with the world, and how much (if any) was "already there"? Is perception the reception of information or the creation of information? -

Is there an external material world ?But it isn't. It's not 'directly' aware if the vibrations in the phenomenological sense of 'aware' (damn terminology problems again). I don't know spider neurology, so I'm going to replace it with human neurology instead.

Something like colour is modeled by a couple of regions in the brain (V4, BA7, BA28...). What we call an experience (what we relate when we're talking about it, what we react to, what we log) is several nodes removed from either the V4 region or the BA7 region.

When articles like the one you cited talk about 'directness' they're talking about it in system terms. Direct means that the internal states have access to it within the Markov blanket. It doesn't mean our experience has no intervening nodes.

So I'm not seeing the phenomenological argument that we 'experience' the model directly but the hidden state indirectly. In terms of intervening data nodes we experience both indirectly. Our experience neither directly reports the output of the V4 region, nor does it directly report the activity of the retinal ganglia, nor does it directly report the photon scattering from the external world object. It doesn't directly report any of them. So why give the modeling output from V4 any unique status in the process? — Isaac

Then this shows that trying to understand the philosophy of perception by referring to the cognitive science of Markov blankets is a mistake, as @Janus seemed to say earlier. It is better to understand it exactly as I described it in that last post:

The same external cause causes one person to see a red dress and one person to see a blue dress. There is a qualitative difference to their experiences. The words "red" and "blue" in this context refer to some quality of their respective experiences. We are directly aware of this red or blue quality, and through that quality indirectly aware of some external cause that emits or reflects light at a certain wavelength. -

The Death of Roe v Wade? The birth of a new Liberalism?No exception for life of mother included in Idaho GOP’s abortion platform language

By a nearly four-to-one margin, Idaho Republicans at the state party’s convention in Twin Falls rejected an amendment to the party platform on Saturday that would have provided an exception for a mother who has an abortion to safe her life. -

Is there an external material world ?Possibly. I've never gotten clear how indirect realism is using the term 'indirect' (nor, for that matter how direct realism is using the term 'direct'). One of the things I thought might come out of this discussion. — Isaac

The article I (and you) referenced above offered an analogy to explain this. The spider is directly aware of the vibrations and indirectly aware of the fly.

In terms of human sight, as I explained before, the same external cause causes one person to see a red dress and one person to see a blue dress. There is a qualitative difference to their experiences, which is why we don't say that they both see a red dress or both see a blue dress. The words "red" and "blue" in this context refer to some quality of their respective experiences (and perhaps also to some property of the external cause, but a failure to recognise the reference to some quality of the experience will lead to equivocation). The qualities of these experiences are equivalent to the vibrations in the spider analogy, and the property of the external cause – emitting or reflecting light at a particular wavelength – is equivalent to the fly.

And in terms of the epistemological problem of perception, the indirect realist will say that how the world looks and how the word feels doesn't tell us anything meaningful about what the external world is "like" (other than the trivial fact that it is such that it causes us to see this or feel that), whereas for the direct realist the external world is "like" we see and feel things to be (although some direct realists will only say this about so-called "primary" qualities like shape, not about so-called "secondary" qualities like colour). -

Is there an external material world ?

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2017.0792

Hidden causes are called hidden because they can only be ‘seen’ indirectly by internal states through the Markov blanket via sensory states. As an example, consider that the most well-known method by which spiders catch prey is via their self-woven, carefully placed and sticky web. Common for web- or niche-constructing spiders is that they are highly vibration sensitive. If we associate vibrations with sensory observations, then it is only in an indirect sense that one can meaningfully say that spiders have ‘access’ to the hidden causes of their sensory world—i.e. to the world of flies and other edible ‘critters’.

So if hidden states are only seen indirectly then what is it that is seen directly? The “internal states”/“sensory states”? What are they?

The example given of spiders seems to suggest what I’ve been saying: that it’s the “sensory world” that is being directly experienced, not the external cause. -

Is there an external material world ?What sort of thing is this "hidden state"? — Banno

I don’t know, it’s Isaac’s thing. I’m just going along with it. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)You wouldn’t care if they were doing crack and hookers. That’s mighty lenient of you. — NOS4A2

I am a liberal. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)I thought you of all people would be reporting on the criminal behavior of the first family of the Uniter States. — NOS4A2

Not if it was doing drugs. I'd care if they're trying to interfere in an election or abuse their position in the White House to enrich themselves. -

Is there an external material world ?Shall we go through https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Quining-Qualia-Dennett/b00cba53a3744402b5c52accea35bff6074a38a9 again? — Isaac

I don't think what I'm saying depends on "qualia". All it depends on is the fact that when you see the dress as black and blue and I see it as white and gold there are differences in our experiences, not in the external stimulus, and that these differences are described using the words "black and blue" in the case of your experience and "white and gold" in the case of my experience. Therefore, these terms in this context refer to the nature of our experiences, not to the nature of the stimulus which is the same for both us. Maybe experiences are qualia, maybe they're brain activity, maybe they're something else.

You might also want to use colour words to refer to some property of the external stimulus, but then that's a case of the word "red" meaning one thing in one context (the nature of the experience) and one thing in another context (that it emits or reflects light at a wavelength of 650nm), with the word we use to refer to the external property determined by the word we use to describe the effect it has on (most of) us. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)I honestly feel bad for the guy, and for many in this dysfunctional family, but the fact this man has avoided jail is the height of privilege. — NOS4A2

I thought you of all people would be in favour of people living their lives as they like. What's wrong with drugs and hookers? If I were you I'd complain about the laws rather than some people not being prosecuted for breaking them. -

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)Why the fuck is the US government considering gifting the semi conductor industry 50 billion? — Benkei

Because either a) they own stock or b) they'rebeing bribedreceiving donations. -

Is there an external material world ?There's a hidden red state, which he's less effectively taking a policy of treating as blue. — Isaac

He sees blue.

I honestly think you might be a p-zombie. -

Is there an external material world ?We've been through this. If I mistakenly call the person in the doorway Jack when his name's really Jim, I'm still referring to the person in the doorway. I'm just doing so badly. — Isaac

It's not about what he says, it's about what he sees. He sees a blue dress. If there is no hidden blue state then him seeing something blue has nothing to do with there being some hidden blue state. -

Is there an external material world ?Where is this visual percept with properties such as colour and shape. Whereabouts in the brain is it stored? — Isaac

I don't think consciousness is "stored in the brain". Consciousness is a product of brain activity, perhaps as some emergent phenomena. The hard problem of consciousness hasn't been resolved yet.

So where is your evidence for data traveling from the inferior temporal cortex where object recognition takes place to the BA7 or V4 regions which process colour? — Isaac

I don't know much about the mechanics of the brain, but that's irrelevant to this particular issue. This is a matter of what words mean. If the hidden state is "red" (as you say) but it causes person B to "wrongly" see a blue dress then the "blue" in "see a blue dress" doesn't refer to any property of the red hidden state. So what does it refer to? If seeing a blue dress is a response to stimulation then the word "blue" in this context refers to some feature of the response, not the stimulus. -

Is there an external material world ?They do not see any visual percept at all. — Isaac

I know they don't, that's the point. Their body is stimulated by and responds to external stimulation but they don't see. Therefore seeing has nothing to do with being stimulated by and responding to external stimulation (except in the trivial sense that stimulation is often what causes those of us who don't have blindsight (and who aren't blind) to see).

We see when there is a visual percept, and the features of this visual percept (e.g. colour and shape) are not properties of whatever the external cause of the sensation is.

When hidden state X causes person A to see a red dress and person B to see a blue dress, person A and person B have different visual percepts, and the words "red" and "blue" refer to some property of their respective percepts, not to some property of hidden state X.

If, in your example, the hidden state is red, not blue, then what does the word "blue" refer to when we say that person B sees a blue dress? Some quality of his inner experience. -

Is there an external material world ?we're talking about seeing in terms of the process triggered by light entering the retina — Isaac

I'm not. I'm talking about the experience of seeing a red dress or hearing voices. I referenced it before, but see blindsight. Their body is stimulated by and responds to external stimulation but there's no visual percept. They don't see. And the features of that visual percept (e.g. colours and shapes) are not properties of the external stimulation but properties of that visual percept. -

Is there an external material world ?We are talking (when we talk about perception) not of hallucinating, nor of dreaming, nor of imagining, but of seeing. If there are multiple senses of the word, then in the case of the dresses you posted photos of, we are discussing that latter sense. — Isaac

People with schizophrenia hear voices. We see things when we dream. This is a perfectly ordinary and appropriate way to speak.

And when we dream, there are colours and sounds. These colours and sounds aren't some hidden external state; they're properties of the experience.

The colours that we see and the sounds that we hear when we're awake are the same kind of colours that we see and sounds that we hear when we dream. The only difference is that when we're awake the experience is triggered by external stimulation and when we dream the experience is triggered by "random" brain activity. -

Is there an external material world ?The latter kind of seeing and hearing is separate from the former kind, and the latter can happen without the former (e.g. when we dream or hallucinate). — Michael

And I'll add, the former can happen without the latter, e.g. when someone has blindsight. -

Is there an external material world ?I don't see how. 'Seeing' involves light entering the retina. — Isaac

Because there are two different senses of "seeing" (and "hearing") as I have said. There's the seeing in the sense of light entering the retina and hearing in the sense of sound entering the eardrum, and there's seeing in the sense of the visual awareness (seeing a red dress) and hearing in the sense of auditory awareness (hearing music).

The latter kind of seeing and hearing is separate from the former kind, and the latter can happen without the former (e.g. when we dream or hallucinate). -

Is there an external material world ?we respond to outputs from Bayesian models as part of the process of seeing external hidden states. — Isaac

That "response" is seeing a red dress or seeing a blue dress. -

Is there an external material world ?This is the problem. You're saying that seeing1 hidden state X causes person A to see2 a red dress and person B to see2 a blue dress. Two different sense of "seeing".

Or to tie this back into what I was saying before about the two different sense of "red": you're saying that seeing1 a red1 hidden state causes person A to see2 a red2 dress and person B to see2 a blue2 dress.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2025 The Philosophy Forum