Comments

-

David HumeI don't object to Bayesian inference.

But that's not induction. — Banno

Wiki says:

As a logic of induction rather than a theory of belief, Bayesian inference does not determine which beliefs are a priori rational, but rather determines how we should rationally change the beliefs we have when presented with evidence. We begin by committing to a prior probability for a hypothesis based on logic or previous experience, and when faced with evidence, we adjust the strength of our belief in that hypothesis in a precise manner using Bayesian logic. -

David HumeSO folk think that by dismissing induction I am dismissing science. Noting could be further from the truth. — Banno

SO how strongly do you doubt an inductive conclusion? Do you doubt it absolutely? Or is that unreasonable?

It’s a funny thing. Folk can really hate Cartesian doubt being applied too liberally. They bang on about not denying what you believe in your heart, not doubting the knowledge you are prepared to act upon.

Yet they talk as if there are no grounds to believe inductive methods of reasoning. And this red herring of deductive validity is all that is offered as an excuse. Whereas the beliefs we are prepared to act on are all derived from inductive generalisations. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismThe version you give is one version, but as you know there are multiple versions for the origins of the suppression of fertility signals. — schopenhauer1

But then any version exhibits a belief that the biology counts. Biological evolution suppressed it. Not culture and its impact on cognition.

It's like plastic tits, fake bums and trout pouts. You can blame modern culture for amplifying instinctual signals, but not for creating them.

Okay, so you recognize that the ability to have more possibilities of thought (due to our lingusitic-cultural architecture) has provided us the ability to reflect on existence itself. Something no other species can do. The exaptation that comes from this is we can also see the absurd nature of living. We can have those existential angst moments and see things as repetitious, meaningless, etc. These are things which evolution did not necessarily provide for, but which is a result nonetheless. — schopenhauer1

And then to the degree that there is cultural evolution - a continuation of the Darwinian game - a failure to successfully reproduce will lead to elimination from the meme pool.

If only anti-natalism could have some meaningful braking effect as 7 billion people become 10 billion by 2050 (give or take a few planetary catastrophes along the way).

Well, this is the assumption you make that annoys me about your self-group argument. You have an assumed (or hidden) underlying teleology in your theory. The group through dynamics is not just "doing" but somehow "progressing" and this is a value judgement that is inserted in the story you present. Though, I understand you do think that "progress" may lead to "extinction" due to fossil fuel overload (and it is almost too late). — schopenhauer1

Huh? I am always explicit on the telos.

What we are doing is the unthinking expression of the thermodynamic imperative. We find all this fossil fuel just sitting in the dirt. We can't help just building a great big bonfire out of it.

If we were thinking - and hoping to progress - we would realise that the fossil fuels are driving us. We are blindly responding to their open invitation. If we had any real utopian dreams, we would get back to living off the solar flux. Or waiting until we had the technical means for something actually long-term sustainable, like perhaps fusion power.

Thank you for your concern (or what looks like concern). However, existential thinking is squarely what is most important as it is our day-to-day lives and evaluations of our lives. — schopenhauer1

Well I am saying being passive is another choice. And one that relies on a faulty understanding of human nature.

If you complained quietly to yourself, you of course would get no reaction. But instead you post thread after thread with the same self-pitying lament.

To the degree you have some biological depression (brought on by a social situation), then sure you may get sympathy. And advice.

But a few of us may be here just to discuss actual philosophy. So a BS argument then deserves a good kicking. No apologies or excuses required. -

TPF Quote CabinetI know, you'll argue that Deleuze's rhizomatic machinic assemblages begin from difference, but if Protevi is any judge, we've seen how a gestalt can act for him via something like 'distributed cognition' as a structural whole whose meaning can be determined beyond particular cogntitions of its participants.

If difference really precedes identity, then a gestalt can never encompass its particulars via distributed cognition, but rather each particular is already its own gestalt. This is how the social field functions in relation to the individual for Heidegger and Derrida.

What's not to love about PoMo? :P -

David HumeWas Kant's transcendentalism not rationally derived from the foundation of all possible forms of intuition? "Empirically real but transcendentally ideal" — Perplexed

That's a different issue. I was talking about the belief in mind-independent truth - the world as it would be experienced even when not being experienced. :)

Do we have to assume here that the concerns of the knower are paramount? How can we be justified in stating that further details cease to matter? — Perplexed

We know that further details cease to matter because they cease to make a difference. How we understand things to be has become sufficiently invariant.

So yes, we are the ones drawing that line. But also, we can do it in a methodical fashion. That is what the scientific method seeks to codify as best as it is able.

Collectively we get together and develop some standards of acceptable evidence. We can get pretty rigorous - like when insisting an experimental effect must pass five sigma significance to be publishable.

We know our inquiry has been exhaustive when we feel sufficiently exhausted by it!

If we are searching for our lost house keys, we might look in the bread bin twice or maybe even three times just to be sure. But much more is OCD. Doubt becomes pathological when it ceases to achieve a different result. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismI'm not a primatologist, so won't pretend to know all these instincts but a major one I can think of is chimps have estrus and cyclical reproduction. They can't help but have a mating season- which implies they cannot help but have offspring. — schopenhauer1

That's a good example. And one that I was going to mention as an argument in the other direction.

It is theorised that the human shift towards the extreme K strategy end of the mating spectrum - the heavy investment required to being able to raise babies born neurally half-baked and utterly helpless - meant that something had to change to foster strong pair-bondings. Dads had to be given a biological incentive to stick around with the mum.

So the suppression of fertility signals was a neat trick. A male wouldn't know when a female was in heat. There wouldn't be the fighting over the right to mate, and instead the strategy would be to stick close with a female and bond by mating continuously. Females of course still might feel sexier at certain times of the month and go do a little cheating - playing the evolutionary game to their own advantage.

So yeah. Check the literature and all these kinds of things have been well debated.

In this case, it says dads can't help getting roped into being dads, even if the babies may frequently be secretly someone else's. The biology has been set up to nudge behaviour in that direction.

Thus there is an innate raising a child instinct along with a learned aspect of how to raise the young, but still seems to not be a choice. — schopenhauer1

It is good that you are steadily backing away from your original claim of some abrupt evolutionary leap from instinctive to linguistic behaviour.

But in your determination to make anti-natalism a valid philosophical viewpoint, you will still pretend that the desire to have children, the positive joy it can bring to lives, is somehow unnatural.

So far you are not producing the evidence.

The simple logic of Darwinian selection says that producing the next generation has to be the game, whether we are talking of that selection applying at a biological level or a socio-cultural level of evolution.

Sure, there is a sense in which society has become a super-organism with its own existential desires now. You can make that argument - as I do. So as individuals, we are being swept along by forces beyond our control.

But then the other side of that is that this aways was the case. We always were being swept along by evolved and successful cultural structures. And the idea that we have an individual choice is a new feature of the contemporary social order. It is an extra wee trick inserted into the game to increase the possibilities of cultural control while also increasing the requisite variety that evolution itself needs to feed off.

We are culturally evolving to become more culturally evolvable. And that could be a rewarding or unpleasant thing - largely depending on how well it integrates or conflicts with our biological heritage.

The other point I always make is that we can only understand this current phase of our cultural evolution of a species in terms of the exceptionalism of being in a period of exponential, fossil-fuel enabled, species growth.

If there are stresses and strains, it is hardly surprising as this is - right now - a historical rupture in the evolutionary trajectory. In about the space of a century, we are deeply changing what it means to be Homo sapiens.

I'm dubious about the Singulatarian argument. But we can see how one thing follows another with accelerating pace. Social media is producing a world of people with a different mentality.

I guess this is what particularly annoys me about anti-natalism. There is this furious change going on right now before all our eyes. It should be fascinating as well as scary. And then we have all this whiney self-absorbed pessimism.

I understand why there might be an actual epidemic of depressive illness. I understand why there might be a feeling of existential helplessness. But those are symptoms of the more general rupture. And philosophy ought to be focused on where that is all heading. We don't know how to judge it because it is still happening. Meanwhile if you are depressed and helpless, seek treatment. Learn how to dig yourself out of your hole as best you can. Don't use philosophy as your excuse for inaction. Don't use it to block the possibility of making your own life better. -

David Hume...the fact that he may not have had much (acknowledged) influence on the mainstream thus far says more about the mainstream than it does about Peirce. — Janus

The social reasons for his relative obscurity are well documented. And many factors combined.

It did not help that he was American in that era of European domination. It did not help that most of his best work was unpublished jottings and he never wrote a cannonical book. It did not help that he was overwhelmingly ambitious in the scale of his metaphysical project exactly when the mood was harshly against that. It did not help that he was also a real working scientist and approached philosophy from that direction. It did not help that he was plunged into great poverty and academic disgrace by having an affair - something scandalous in prim Harvard, which would have been laughed off back in Europe.

Personally, I thought Peirce was pretty cranky when I was first introduced to his stuff. Then I thought, well some of his ideas certainly seem to foretell of what we are discovering now. And then eventually I found that on any deep issue at all, Peirce seemed to have it covered.

Give it another 100 years. His due will be given. -

David HumeThe thing is, if we concede that knowledge is only practically rational does this not mean that there is truth only with regards to certain ends? — Perplexed

That is how you attack the Jamesian strawman version of pragmatism.

The actual story here is that truth is the limit of rational inquiry. It is what we will believe in the end following an exhaustive pursuit. And so it is what becomes invariant within our belief structure.

So yes, this is not the good old fashioned truth of the transcendental kind - that which is true even despite there being no one around doing the knowing. The rationalist pipedream that has had such a manic grip on so many.

It is truth defined in terms of the concerns of a knower. It is a search for justified answers to the point of exhaustion - which itself is in turn a search to the point that further details cease to matter.

Pragmatism only seeks to constrain uncertainty. It can't be eliminated. And so truth - as a natural limit on a reasoned process of inquiry - is found at the point where we can afford to become indifferent to the uncertainties not yet eliminated. Our purposes - in whatever sense they exist - are sufficiently satisfied. We can't then pretend to continue to doubt - to be entranced by the remaining uncertainties - if that is merely unsatisfied knowledge that is also held by us to be of no account.

So pragmatism includes the self in its world. Truth is defined relative to the wants of the observer.

Of course that then does bring in a new issue. We can distinguish between the highly subjective view and the highly objective one. Most folk think of "true truth" as being the kind of completely invariant knowledge that scientific-strength inquiry will bring.

But even this is very slippery. The invariances that pop out of science are general principles - ideally, the mathematical symmetries encoded in foundational equations. They seem rather ... abstract. Platonic even.

The material particulars of the world become numbers - more abstracta! - that we plug into the equations. The subjective observer is suddenly rediscovered at the heart of this maximally objectivised knowledge as the entity who must informally carry out an "act of measurement". To turn the phenomenal experience of the world into the values input into an equation is a tricky and un-formalisable step.

This is what strikes directly at the fantasy of deduction being somehow foundational. A valid syllogism is only ever going to be as truthful as the semantic cargo we plug into it.

But anyway, we have quantum theory now. Nature is really rubbing our noses in the impossibility of knowledge that is objectively true in the absence of an observer who actually does something to constrain the outcome with a choice.

We know the rationalist pipedream to be physically impossible in a foundational fashion. -

David HumeThe basis is not purely rational (unless you follow Kant's solution) but practically rational. What more do you want? — Janus

Heh. The glass that pragmatism knows to be 99.99 percent full is always going to be frustratingly empty for those who still ache for Platonic certainty. If you believe in all or nothing, then that's what you want to be the case, despite the facts. -

David HumeI had a quick look and Peirce hardly gets a mention in Popper's Logic of Scientific Discovery. Pragmatism is only mentioned in passing. — Banno

As to Peirce's influence on Popper; I seem to remember reading about it in Unended Quest, but its a helluva long time since I read it and I could be mistaken. — Janus

Popper wasn't directly influenced by Peirce, but did recapitulate the same line of thought. They were especially close on propensities. And Peirce of course was concerned with a much larger metaphysical project of how epistemology could be also ontology.

Later on in his career, Popper found Peirce had been saying the same things and acknowledged this in saying he wished he had known of Peirce's work earlier (Of Clocks and Clouds) and that Peirce was "one of the greatest philosophers of all times" (Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach).

Similarly when Bertrand Russell learnt about Peirce in later life - having waged his war against Jamesian pragmatism - he took the view, that "beyond doubt [Peirce] was one of the most original minds of the later nineteenth century, and certainly the greatest American thinker ever."

Cheryl Misak has now documented the subterranean influence that Peirce had on Wittgenstein via Ramsey and Lewis - https://jhaponline.org/jhap/article/view/2946

Peirce was so much ahead of his time - and also working in unfortunate circumstances - that it is only recently he has started to have his rightful impact on academic thought.

I was in a similar position. Via cognitive neurobiology, theoretical biology and paleoanthropology, I had arrived at a generally semiotic position. And then decent digests of Peirce's voluminous unpublished thoughts began to pop up. Along with a whole circle of biologists and systems scientists, it just became obvious that Peirce had sorted out the metaphysics 100 years earlier. Within a few years, we were all calling ourselves biosemioticians. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismSo compared to our closest non-linguistic relatives, like the chimps, bonobos and gorillas, which instinctive behaviours have we lost? Be as specific as you like.

(Birds have brains that evolved as elaborations of the basal ganglia rather than of the primitive olfactory association cortex as in mammals. There is a reason why they might have more stereotyped inherited action patterns.) -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismThe decoupling of instinct from general processing is not an easy story. I'd like to see this. — schopenhauer1

But it is your contention that there is a decoupling rather than an integration. So frankly I have no idea what you are on about. Just as I don’t know where you are getting this general processing notion from.

But if you can provide the references, that would be sweet. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismSo now you want a free seminar on cognitive neurobiology? What’s in it for me? :)

-

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismThe human brain works more like generalized processor, with the vehicle of linguistic conceptualization as a way of integrating memories, thoughts, images, etc. How can these concepts said to be pre-linguistic (i.e. innate)? — schopenhauer1

Well no, the brain don’t work that way at all. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismBut do these preferences come innate or only after being enculturated in a social setting? — schopenhauer1

Given that the individuation of a psychology is a blend of both influences from birth - as I said - then you can see why this is a silly question.

The default answer on any aspect of psychological being is going to be "both, together, resulting in an integrated whole". -

David HumeThe best I can do in this case is to ask further questions for the purpose of clarification. — Magnus Anderson

But I asked you for clarification about this "relevance" of yours. For me, there is a background metaphysics that explains the specific relevance. For you, there must be likewise some background metaphysics - given that it seems you must have some good reason to reject my metaphysics as a relevant grounding.

So what is this metaphysics exactly? Put it on the table. -

David HumeI am just trying to understand why you place so much emphasis on it. — Magnus Anderson

So did I make a big thing of it, or have I just replied to your continuing questions about it?

I don't see why such a concept is relevant. — Magnus Anderson

Fine. And yet you kept asking anyway. And I kept explaining why I do find it relevant. And so far you haven't rebutted my reasons for finding it relevant. And importantly so. Yet you want to keep telling me you don't find it relevant - despite offering no supporting reasons.

And if what I say appears to be an attack then it's merely due to the possibility that some of the things you say are no more than smokes and mirrors. I have to entertain such a possibility. — Magnus Anderson

I'm not bothered by your attack. I'm more disappointed at its lack of bite.

You don't have to if you don't want to. — Magnus Anderson

It's not a case of not wanting to. You have simply failed to supply an argument that could be evaluated. -

David HumeBut instead of talking about induction, or more generally intelligence or thinking, you talk about abduction. — Magnus Anderson

I'm not following you. I've talked about all those things. You seem to want to make some campaign against abduction as a concept. And I am interested in how abduction fits into a holistic and naturalistic scheme of reasoning.

You will have to explain why I should be concerned by your problems with seeing a relevance in abduction. I've already explained why it would be relevant to a metaphysics that is irreducibly triadic (rather than dyadic or monadic).

And instead of speaking in terms of regularities or patterns, you speak in terms of constraints. — Magnus Anderson

Constraints generate regular patterns in a probabilistic fashion. So that is how science understands physical systems. And it is how we would speak of nature if we take a systems view where we grant generality a reality as a species of cause.

So again, it is simply a reflection that I am arguing from a consistent metaphysical basis. It is how reality would be understood if you believe in an Aristotelean four causes analysis of substantial being. -

About the existence of a thing.OK. So you have recapped the gist of Ancient Greek metaphysical dilemmas. Let's jump to the resolution.

Individuation is always true from some point of view - some scale of observation. The world is a process. It is always either relatively individuated in some fashion, or relatively not individuated. But for the sake of simple world modelling, we like to construct a sharp dichotomy that separates all things into two categorically opposed baskets - flux and stasis, change and stability, potential and actual.

We can begin to see the fluidity of this interplay - this oscillation between the limits of two poles of being - once we understand every individual, every substantial being, in a multiscale fashion. That is, a hierarchically-ordered point of view which spans all the "cogent moments", or integration scales, of any entity that appears to exist in space and time.

So look over there. I see a river, a mountain, a wave, a wind ripple passing through the grass.

The mountain must have existed forever - from our typical human-scale perspective that also sees the wave as not really a proper entity at all but just a momentary disturbance in the water.

But if we had eyes to watch a landscape over millions of years, we would see a geography as fluid and turbulent as the surface of the sea. The rivers would snake and twitch, disappear and reform, with even greater abandon.

Likewise, if we zoomed in on any fleeting entity, its existence would start to stretch out so that it seemed completely permanent and substantial compared to our scale of individuation.

So a modern metaphysics would see everything as a process. And what differs is the characteristic rate at which some part of the world becomes individuated from the general backdrop in some significant fashion - before disappearing back into that backdrop. -

David HumeA graven image. It should have an all-seeing eye at its centre. Another odd example of the obsession with trinities that helped kept Pierce from mainstream approval.

None of which should be taken as disparaging Bayesian analysis and other legitimate and excellent work around this topic. Unlike the philosopher's notion of induction, and even worse, abduction, Bayesian approaches have a strong standing. — Banno

Rock it like it's still the 1970s! -

David HumeThe question is: do you agree that abductive reasoning is a specific type of inductive reasoning? — Magnus Anderson

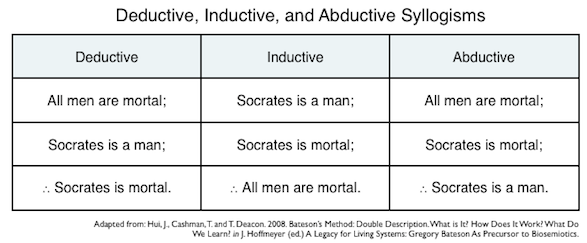

I'm not getting too hung up on the divisions. There is the more familiar dichotomy of deductive vs inductive argument - necessary inferences vs probable inferences. That kind of works in the sense that deduction proceeds from the general to the particular with syntactic certainty while induction does the reverse of going from the particular to the general with provisional hopefulness.

But then a triadic view - one where a dichotomistic separation resolves itself into a hierarchical structure - is the special twist that Peirce brings to everything. It is the next step which completes the metaphysics.

So that is why it is a neat result - one that hierarchical structuralism predicts - that the actual process of human reasoning splits itself so cleanly into a trichotomistic process. It makes reasoning not an arbitrary business but one that works in the same basic way as the nature it wants to describe.

This is obviously a huge metaphysical deal - for those who still have faith in metaphysics as a grand unifying project.

So is abduction a specific form of induction? The Peircean question is instead where does abduction fit in the basic semiotic triad.

And it slots in as Firstness. A hypothesis is the first free and spontaneous act, which then leads to the "deductive" secondness that is mechanically determined reaction, and followed then by the thirdness which is the generalisation of such individual reactions to the form of some regular and enduring global habit.

Here's an example of abductive reasoning:

1. The grass is wet.

2. If it rains, the grass gets wet.

3. Therefore, it rained. — Magnus Anderson

But is it?

The classical deductive syllogism is:

Major premise (or the general rule: All M are P.

Minor premise (or the particular case): All S are M.

Conclusion (or result): All S are P.

Abduction then rearranges the order so that the argument is: All Ms are Ps (rule); all Ss are Ps (result); therefore, all Ss are Ms (case).

So you would have to say something like:

- Rain makes things wet.

- This grass is wet.

- Therefore, the grass was (probably) left out in the rain last night.

It is quite apparent to me that abductive reasoning is a very narrow form of reasoning. By definition, it only forms conclusions regarding events that took place in the past. This means that abductive reasoning is restricted to making "predictions" about the past. In other words, it can only be used to create retrodictions. This is unlike induction which can be used to form beliefs of any kind. This suggests to me the possibility of you defining the concept of induction narrowly as pertaining only to making assumptions about the future. — Magnus Anderson

I'm not sure why it seems a problem that abduction is retroductive - that the past is being assumed to hold the key to the future. To the degree the world has actually developed some stable intelligible being, it will have developed those general constraints which serve to restrict freedom and spontaneity to give the world its predictable shape.

This is the point concerning the metaphysics. Rather than going with the classical metaphysics which thinks reality is some God-given realm of law and deterministic material action, Peirce is up-ending that view to build a logic that arises out of a completely probabilistic model of existence.

So again, induction is not a problem as it sits on the side of probability. Deduction is now the problem as the shallowness of a deterministic or mechanical metaphysics stands exposed. The issue is really why would deduction function at all? And clearly - just as we find with computers and other machines - they can't stand alone. They are helpless if it weren't for us to bookend them and makes sense of their furious syntactical whirrings.

So if you sit on the side of a probabilistic ontology, now the whole picture can snap into place properly. Abduction seeks out the constraints that must underly any observable regularity in the world. A classical/deductive/mechanical/deterministic/atomistic world is merely the emergent limit on this probabilistic description. So the task is to guess at the rules that stabilise things sufficiently that the probability of causal certainty approaches arbitrarily near 1 (or 0) for the things we might care about as fundamental facts of the world.

Will we always fall down rather than up when stepping off that cliff? Well thermodynamics says all our atoms could fluctuate upwards at that precise moment and give us a surprise. Yet also, that is almost surely never going to happen - even given a really vast number of lifetimes for our Universe.

Thus abduction does seek to recover rules already formed. And inductive confirmation seeks to show our guesses are correct. And it is all couched in probabilistic language. We no longer believe in a classical Cosmos - the one of Newton and Hume. We are presciently already into a quantum reality where concrete classicality is an emergent and inherently probabilistic limit state.

When I guess that the next value in the sequence 1 2 3 4 is number 5 I do not necessarily do so because I am aware of the underlying pattern. Rather, in most cases, we do so because we know that the superset {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} has the highest degree of similarity to the superset {1, 2, 3, 4} among the supersets that have the form {1, 2, 3, 4, *}. — Magnus Anderson

I'm sure the rule you abduce is the simper one - 1+1=2. And so on, ad infinitum.

So you abduce a deductive rule, an algorithm that blindly constructs. You are recovering the set theoretic approach that is already the axiomatic basis for number theory.

A cherry-picked example which is a textbook case of deductive thought is hardly a good way to illustrate an argument about the true nature of induction. :-}

Regarding AGI research, most of the research has been dedicated to modelling how the world works rather than to modelling how thinking works. I think that's the problem. Rather than having a programmer create a model of reality, an ontology, for the computer to think within, it is better for a programmer to create a model of thinking which will allow machines to create models of reality -- ontologies -- on their own from the data that is given to them. — Magnus Anderson

Well that is why I always say forget Turing Machines and symbolic logic. It is neural networkers who have been thinking about how to properly mimic the Bayesian principles by which a brain actually makes inductive predictions. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyOK. But I am finding your whole position a struggle to follow. So this would seem the missing link.

And yes, a proper understanding of what we might mean by the consciousness is central to having a position. I've been making that point. People hereabouts have been using Wittgenstein as if he absolved us of a need to have a background metaphysics in this regard. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyWe talk about facts using the concept fact, and that concept refers to states-of-affairs, but even without the concept, or without minds to apprehend the facts, there would still be states-of-affairs in the universe. Those facts have an existence quite apart from a mind, and quite apart from any linguistic reference to them. So there is an objective reality in back of our language, but how we talk about that reality takes place in a community. — Sam26

We don't need to be idealists to see that this is wrong. Talk of states-of-affairs only makes sense in relation to talk of points-of-view. And whether we talk of the point of view being subjective or objective, it is still a point of view.

Of course, in practice, we live in a world where it is full of mind-independent events and objects and voids. We don't need to be idealists in our ontic commitments.

But still, we can't then also deny that the very idea of "a state of affairs" is a world description that demands a viewer or interpretant of some kind. That is why a maximally objective point of view is often called the God's eye view - the view from nowhere which is also the view from everywhere.

It gets worse for the naive realist as, in practice, this maximally invariant viewpoint has to start to see the "laws of nature". It has to transcend the nominalist particulars - all the medium-sized dry goods that seem to populate a world that is "a state of affairs" - and focus on what is maximally general or universal about the world being viewed. The local particulars become the contingencies or the accidents in being just the individuated variety contained within the general constraints or invariances.

So the concept of states-of-affairs carries with it both the need for some viewpoint - the maximally objective one - and also a viewpoint that then adds a nominalist fixation on the contingently individuated. It is the viewpoint that reduces the world to some instantaneous collection of concrete particulars.

Thus the very idea of a "state-of-affairs" incorporates a complex metaphysical position. There is nothing direct or simple about it. And to say that the facts of the universe exist in a mind-independent fashion is both true - in regards to an idealist metaphysics - and untrue, in regards to a properly holistic metaphysics such as the triadic model afforded by semiotics. -

David HumeAnd all of this is apples and oranges anyway because while there may be a limit to what inductive reasoning tells us about the actual world, deductive reasoning tells us nothing about the world. It tells us only about whether truth has been preserved from our premises, yet there is no suggestion (or requirement) that our premises be a truth about the world (e.g. all glurgs are gurps and all gurps are glomps, therefore all glurgs are glomps). So, you can talk about the limitations of inductive reasoning, but the limitations of deductive reasoning are more severe, as it tell us nothing at all other than whether we've correctly solved our Sudoku puzzle. — Hanover

Thank goodness for some commonsense.

The interesting thing was that a valid deductive syllogism could be defined in terms of the three elements, the three steps, of a rule, a case, and a result. Some general "truth" that ranges over a class, some particular instance of that class, and then a consequence that could be predicated of that instance as a necessary fact.

And then the question arises of what happens when you play around with those three elements and consider what they say in a different order.

Induction was hazily understood as a converse of deduction - a step from the particular back to the general. But Peirce pursued the idea that induction itself was distinguishable into abduction and inductive confirmation. That was the way we actually seemed to reason about things in pragmatic fashion. And it was the way that science was turning into an explicit epistemology. Now you could see that this triadic story was itself already revealed in the formal tripartide structure of a deductive syllogism.

Of course the two varieties of induction were both "invalid". To go from the particular back to the general must involve a probabilistic leap of faith. A willingness to believe rather than to doubt.

But the whole problem with deduction is that it can't itself ever derive new information. It is just a system of syntax. It can only rearrange whatever semantics you put into it in a way that makes that move from the general to the particular.

So the "problem" with induction was really a problem with deduction. It was the rationalist dream that deduction could yield certain knowledge about everything. And in fact, by itself, it can yield no new knowledge at all. You needed induction to get the game started and to pragmatically justify the results.

The puzzle for me is that Banno keeps contradicting himself on these issues. One minute he is attacking the sceptics who just refuse to be pragmatic and commit to a belief that works. The next he is attacking the inductive basis of that pragmatism on the grounds the truth is "out there" beyond any such probability-based understanding.

Either he just hasn't sorted out a basic incoherence in his own epistemic metaphysics or he has something further to say which he just can't seem to bring himself to say. It's all very curious. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismWhat kind of content would you predict that a social species with a big natural interest in social dramas might find gripping? Stories of love, hurt, power and status? Stories that really engage their emotions?

-

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismWhat you cannot do is prove what is an innate instinct and what is socially constructed. Do you think "nurturing" is just an instinct or a tendency or preference that an individual may have towards something that originates by being provided the tools of personality/ego/introspection/environmental interaction that comes from a socially constructed mind? — schopenhauer1

I’ve already said there isn’t a sharp line as the two things are blended in development. The self is a mix of nature and nurture. It’s the same story as when we are talking about IQ or whatever.

The view being contested was your contention that instinct no longer played a role in humans after language came along.

So you are simply creating a straw man to attack now.

Any overriding metaphysics (like your peculiar brand of Peircian triadic semiotics) can be considered romantic. So, I don't think it does much to throw out this label. You are just creating a false dichotomy and then pitting one romantic vision (the interlocutor's) with your own. — schopenhauer1

Peirce would be a good metaphysics to oppose a bad metaphysics like Romanticism or reductionism. But ordinary science is quite good enough to argue against your claim concerning a lack of biological instinct in modern humans. -

David HumeHmm. Again it is baffling that you sound like you believe this is some kind of devastating criticism.

Abduction finds the assumptions from which conclusions can be drawn. Deduction finds the conclusions that can be drawn from those assumptions. Inductions then confirm that the conclusions support those assumptions in terms of the predicted facts.

Deduction might be semantics preserving in being syntactically closed, but it can’t generate new information. Whereas abductive inference and inductive inference are both probabilistic in spirit and can go beyond the evidence in ampliative fashion.

As I said, abduction does seem a work in progress. It is hard to boil down its holism into some more reductionist formalism.

But another way to get at it is as retroduction.

We can say the particular fact, A, is observed. And if the general fact, B, were true, then A would be so as a matter of course. Hence, there is reason to suspect that B is true.

So it runs deduction backwards from a conclusion to a likely assumption. And it should make you think a bit about why deduction is only secure in going from the general to the particular, while going from the particular to the general is inductive - that is, going beyond the evidence by a willingness to believe a high probability is good enough to be a workable certainty.

Isn’t that just what you always want when faced by these pesky doubters?

But I agree. Once you get into this business of abduction and the full pragmatist story of how we formulate knowledge, you start to see the much larger scope of the project.

Generality must be fleshed out with some kind of best fit principle. And this is the approach familiar in a philosophy of science understanding of the framing of natural laws. We want the generalisation that discards the most information. And that is in fact a balancing act - a best systems account (BSA) that opposes simplicity and strength.

So there you have a link to Ramsey, Lewis, and the like. Abduction can be bolstered by this same principle.

Likewise the principle of indifference is critical to finding a pragmatic grounding to the particular. There are always going to be an unlimited number of potential differences. But at some point - dictated by a purpose - any further differences will cease to make a difference. And we can see how this applies to the inductive confirmation.

So we need cut offs for the general, and cut offs for the particular. When those are supplied, a process of reasoned inquiry can become self-closing in the tales it tells.

Deduction is merely already closed - syntactically. It can’t discover new semantic content.

But deduction sandwiched between abduction and induction has the means to be open enough to learn and create content. Then achieve a satisfactory degree of self-closure. -

David HumeJust drop the word "absolute" and you can avoid vast quantities of philosophical guff. — Banno

So now you prefer the locution to be: "The answer would be that we can't have any kind of truth or certainty."?

Are you sure? Try again perhaps. -

David HumeGiving them a name does not alter their invalidity. — Banno

Calling them invalid does nothing except highlight that their truth claims hinge on matters of semantics rather than syntax.

It's so funny watching you trying to rescue your metaphysical preferences while pretending not to care about metaphysics. :P

Go on. Tell us about lunch again. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismI don't know, looked pretty much like you unwittingly agree, — schopenhauer1

That's what you get for trying to be precise I guess. Folk still don't take any notice. :)

The "I" is largely socially constructed, agreed then. — schopenhauer1

And largely biologically constructed as well. Don't now just ignore that.

However, what you cannot do is a sleight of hand where something that is "intrinsically rewarding" now counts as instinctual. — schopenhauer1

I said both the biology and the sociology can bring their intrinsic rewards. I was disputing your sub-premiss that having a family is intrinsically unrewarding on either account.

So you are now really mangling my reply.

Why have I enjoyed raising a family? I can see both social and biological reasons. It feels very instinctive to nurture. And also being a good dad is a socially approved activity.

You can say - in anti-natalist fashion - that both reasons are bogus. I am a fool for taking them at face value. But if we then take the debate to that level of general metaphysics, as we have before, then I still prefer my naturalistic account to your old-hat clash of Romantic idealism vs Enlightenment realism.

You are stuck in a discontented bind because of your incoherent metaphysics. But I don't find your problems to be my problems.

The decision to have less kids due to hard times, is a calculus based on the very linguistic-cultural brain that can do this sort of rationale. — schopenhauer1

You might also decide to have more kids as - if you are a subsistence farmer - more helping hands is a worthwhile capital investment.

It is situational. The point is that we are good at making choices given a situation. But what troubles us is when we have no particular influence over the situation itself.

So if there is "philosophy" to be done, it ought to be aimed at creating better situations if there is indeed something not to like about the ones we are in.

Of course, your pessimism is predicated on the impossibility of situations ever being good. And stubbornness will turn that into a self-fulfilling prophecy very quick.

This is a live issue. My daughters are in their 20s. I see many in their circle of friends going into self-destructing spirals because they turn in the wrong direction when faced with any challenge.

Now certainly modern society can be blamed for the kind of challenges that the young face. But also, it is obvious that many of them have faced so little actual challenge in their growing up that absolutely everything becomes a challenge as soon as they want to start standing on their own feet.

So it is a complex story. Yet also very simple. Bad metaphysics can really screw your life up. :)

What I am trying to do is show that raising a child is a preference like any other preference- it just happens to be a popular one because of cultural pressures. — schopenhauer1

Yes. You need it to be axiomatic that it has to be an external pressure rather than an intrinsic desire. Yet with a straight face you then also say you are a social constructionist and a naturalist. But if we are socially constructed as selves, then that "pressure" is simply our true being finding its expression. It comes from the self - as much as there is a self for it to come from.

The confusion kicks in because we are then both biological selves and social selves. The communal self we share at pretty basic level. The phenomenological self we share at an even deeper biological level, but also we don't really share at all beyond our capacities for empathy and mirroring.

So there is complexity here again. But don't let it confuse the argument. If you are focused now on the socially constructed self, then you yourself removed the very grounds to complain about any individual preferences being socially constructed.

There is a basic logical flaw in your argument. It shows that you are operating from the incoherent and dualistic paradigm which is Romantic idealism vs Enlightenment realism.

Beyond the obvious physical pleasure involved in sex, the preference for actually procreating is simply in the imagination, hopes, preferences, of the individual just like any other goal that is imagined, hoped for, preferred, etc. — schopenhauer1

No. You just said that the psychology of that individual is largely a social construction. Indeed, you have been arguing that Homo sapiens represents a complete rupture with nature in this regard. Instinct was set aside and we became totally cultural creatures.

Anyway, having said the pressures were social and external, now you are switching to talk of them being internal and individual. The next step in your faulty argument is to then say that is why these individual preferences are falsehoods imposed on people unwillingly. As if they had some other more legitimate self - an inalienable soul. Which you will then say they can't have - as Newtonian physics and Darwinian evolution proved God is dead and life can have no purpose or value.

You have trapped yourself in a bind - even if not one of your own making, but one that simply recapitulates some bad socially-constructed metaphysics.

So how will you react to that realisation? Will you again go through each point and find that I unwittingly agree with you despite whatever I might have actually said? -

David HumeIt seems odd, then, to back up one's belief that the chooks will lay eggs tomorrow with a vast, profound theory of pragmatism. — Banno

What's odd is that you want to waste all your time on a philosophy site ranting against critical thinking.

But I'm guessing you suddenly have a lot of time to waste for some reason. -

David Hume...the first question, which is "how can we hope to have certain knowledge?", will remain unanswered. I think the first question makes no sense at all. — Magnus Anderson

The answer would be that we can't have any kind of absolute truth or certainty. So it is a question that was answered. That clears the field to get on with a pragmatic approach to truth and certainty.

Well, there is still then tautological, deductive or Platonic truth. Folk will want to say deductive logic is at least truth-preserving when the syntax is valid. It maps one state of affairs to another without loss of semantics. We could have a debate about that.

And then there is the allied thing of mathematical truths - the things we say about abstract objects like triangles. We can know those things for sure, in a necessary fashion. Again, we could have a debate about that too.

So in a general way, the absolutism is long dead. Pragmatism rules. But at the fringes, people still want to maintain some kind of unquestionable certainty.

So abduction, if I understand you correctly, is a pattern of no-pattern of thinking. You say that it is the least formalisable pattern of thinking which suggests to me that it lacks pattern to a considerable degree. Or it could be that the pattern is complex and thus difficult to understand and formalise? Which one of the two is the case? I am inclined to think the former but I like to keep my options open. — Magnus Anderson

Not really. I was emphasising how we know it is an important part of successful thinking, and yet we are not sure if we can formalise it. We would certainly like to if we can. One of Peirce's many foundational contributions to logic was to bring the issue out into the clear light of day. I argued that he was less successful at given a proper answer.

My own thinking is informed by modern science and its efforts to build pattern recognising machines, as well as the efforts to understand the same in human brains.

Why do Fourier transforms work so well in signal processing, for example? Why do generative neural networks seem a powerful approach? We do have some mathematical models to consider now.

So if abduction is a process of thinking that has very little pattern within itself, this means that abduction is mostly a random process. It's basically random guessing. — Magnus Anderson

Well if that were so, we would hardly ever arrive at a useful hypothesis. It would take us a lifetime to answer a single question in any ordinary IQ test. It is just a simple fact that we can leap towards the explanations which erase the most information and leave us with the core principle we need to follow.

Our brains do it all the time. The question becomes, how? It certainly ain't a serial search process. It certainly doesn't rely on random exploration. There is something gestalt and holistic in how we can feel the edge of an answer and then watch it flesh itself out into a fully fledged aha!

So the brain is doing something in information processing terms - unless you believe that all such mental activity is connected with divine powers.

If you see a disembodied head lying on the floor you are not going to assume "someone clapped his heads and this head popped out of nowhere" you are going to assume something like "someone's head has been cut off". That betrays order. Not necessarily in reality but in thought. — Magnus Anderson

Yep. So inference to the best explanation.

And what should be noted is that we can imagine a gazillion reasons for there being a disembodied head lying on the floor. Maybe a dinosaur bit it off. Maybe that dinosaur was a pterodactyl or a t-rex. The possibilities are endless.

But no. If we are actually any good at this business of reasoning, we will discard a gazillion possibilities pretty much instantly. We will come up with some maximally plausible guess. We will use all the information to hand and assign some Bayesian process of evaluation that leaves some central body of possibility as whatever is the hypothesis that can't be so easily eliminated.

Even Sherlock Holmes knew that. He was the master of abductive logic after all - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherlock_Holmes#Holmesian_deduction

Abduction has the following form:

1. Event B occurs.

2. When event A occurs event B follows.

3. Therefore, event A occured before B. — Magnus Anderson

Well yes, Peirce did notice that the same terms employed by the classical versions of deductive and inductive arguments could be used to generate a third kind of argument.

So an abductive argument was already contained within the standard formalism. It followed on directly from the truth of those other two. It was there implicit and waiting to be recognised.

That should be a pretty striking fact I would have thought.

If you aren't interested in either induction or deduction, then you won't care about abduction either. But if you do care about those two things, then you have to care about the fact that the same elements just automatically then have a third combination.

-

David HumeThermodynamics is part of physics, not metaphysics. — Banno

Really? Is that the best you can do? -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismSo, despite your protestations to the contrary, your very evidence indicates you believe cultural learning is largely the vehicle for which humans procreate and follow a preference to raise children. — schopenhauer1

Err, no.

I already agreed that sex is the "basic" instinct via the general tendency to prefer physical pleasure, but that is not the same as literally the conceptual idea of "I prefer to raise a child" which involves much higher cognitive understanding and cultural ques than mere physical pleasure. — schopenhauer1

Well when you shift the goalposts that way, then claiming that there is an "I" that has an innate preference is of course what would be countered by a social constructionist point of view on the subject.

You are now framing it as a personal choice. Which in turn demands a Cartesian model of a choosing self.

The argument was about this "self" being unwillingly forced to procreate due to evolved instinct vs being unwilling forced to procreate by some social necessity. And your emphasis either way is on the unwilling. Yet either way, it might be a willing inclination in being an intrinsically rewarding or pleasurable action - the rewards of having sex and then raising a family being something that both biology and sociology would have reason to celebrate.

Based on your own response, the score is:

Cultural learning- 4

Instinct- 1 — schopenhauer1

You mean based on your own spurious marking system.

If you want a score, clearly you are flat wrong in suggesting that Homo sapiens abruptly left behind biological instinct when it became a linguistic species.

And you would be right to the extent that you might then make some more nuanced case for the cultural malleability of our procreational habits.

I mean everyone knows that we respond to social economics. You either have a lot of kids, or try to avoid having kids, depending on the economic equation as you see it.

And even my pet fish - dwarf cichlids - can make that kind of decision. They lay eggs and then either eat them or protect them, depending on some instinctive judgement about the situation in their tank.

So really, the same evolutionary logic is at work, just at a higher level of sophistication.

Anti-natalism depends for its grounding on some kind of anti-naturalistic metaphysics. It arises from being disappointed by the Romantic promise that being alive has transcendent meaning, and then Enlightenment physics saying no, life is transcendently meaningless.

Well as you know, I just reject that metaphysical framing. I take the natural philosophy route on all questions. And that accounts for the issues here with ease. -

David Humeif any of these disbarred tomorrow from following on form today, we would reject them. — Banno

How exactly could you reject them without determining which of them was responsible for some failure of prediction?

You could plan your future with Tarot cards, bedtime prayer, or gut intuition. Those have been pretty everyday habits in the past. Was there some reason they might have fallen out of fashion in the planning of your own life? Or do you still put your avocadoes in a magic box to keep them fresh, or instead a thermodynamic device called a fridge?

What metaphysics does your actual daily routine depend upon? Of course, the fridge might as well be a magic box to you. But the good folk who designed and built it might have needed some more rigorous reality model, don't you think? -

David HumeSo I think Hume had it pretty well right, in describing our acceptance of continuity as a habit. It's not something that requires justification. It's not as if, were we unable to find such a justification, we wold cease to plan our mealtimes. — Banno

Again, it is wonderful that you accept a pragmatic account of truth and rationality. But you are still confusing philosophy with your personal satisfactions.

Animals don't need to have an epistemic theory either. A reliance on an unquestioned habit of inductive generalisation is good enough for their everyday purposes as well.

But I'm not sure why you think that the everyday routine of your eating habits is all there is to say about epistemology. I guess you just enjoy taking an anti-metaphysics stance to its caricatured limit. But in the end, who cares when there is interesting metaphysics to be discussed.

Just don't distract us too much with all your noisy chomping. -

David HumeSo before we invented entropy we could not plan our lunch.

Your account is just too complex. — Banno

Well, maybe some of us have larger epistemic concerns than the world that encompasses our breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Your account is just so shallow. ;) -

David HumeBut the future is not like the past.

Yesterday I had a full bottle of red. Now it is only half full. — Banno

Erm, the story is that the future is like the past in that its total entropy has increased by much the same amount yet again.

The basic constraints in play are the physics of thermodynamics. And Hume/Newton were talking about the physics in play. It was just that that physics was the reversible story of inertial mechanics, not the irreversible story of the Cosmos as a dissipative structure.

So the surprise - the disproof of an inductive metaphysics - would be if your pissed-away bottle of red magically reconstituted again itself each night, like a Magic Pudding.

So yesterday, the slope was downhill. And tomorrow, the slope will still be downhill. That is the inductive claim here. -

David HumeI have yet to see the relevance of introducing the third type of reasoning that is abductive (or retroductive) reasoning. — Magnus Anderson

The relevance is that it introduces a third and missing step in reasoning as a holistic process. And it is interesting in that so far it is the least formalisable. It would be really important if we could add a formal model - a potential algorithmic approach - to our arsenal of intellectual tools.

The unarguable point is that humans are remarkably good at guessing right answers if we took a strictly random search approach to creative insight.

How do we form our intuitions in the first place? It can't just be that we try every possible key to unlock the door. Peirce made mathematical arguments about why a random search couldn't be executed in the lifetime of the cosmos. And the same arguments are made today about NP hard solutions.

Folk like Roger Penrose have really gone to town on the issue, saying it proves to them that conciousness must be a non-computational quantum process. So it wasn't just Peirce. This is an issue that is central to a lot of metaphysical positions, as well as being of great practical interest in human psychology and artificial intelligence.

Peirce actually was leaning towards a pretty mystical answer on the "how" of abduction. He talked of Galileo's il lume naturale. He wanted to use the existence of inspired guessing as a proof of the divine. And so - in that regard - I am hardly peddling the Peircean line. Although that then depends on how you interpret what Peirce actually wrote.

Anyway, my own naturalistic view is that human minds - being evolved to understand worlds - are good at unbreaking broken symmetries. We can inductively generalise and so leap to an understanding of what the unbroken generality must have looked like before it became broken in the particular way it presents itself to us.

This is a Gestalt or Holistic deal. The whole brain is set up to see figure in terms of ground. The figure breaks the symmetry of a ground. And we can then turn our attention to the nature of the ground that had that general potential to be broken.

So the search isn't a random stumble that would take forever. Awareness is already developed in a fashion that represents a symmetry-breaking. It is already broken into figure and ground. Reversing that is just a case of relaxing the mind in a certain fashion to allow the backdrop to be seen in that light. It is a short leap - like seeing the negative space in a reversible Gestalt image of vase and two faces - rather than a blind computational search through every alternative.

I guess it all depends what you think is a central question of epistemology. Is it how can we hope to have certain knowledge? Or is it how is it that we can reason in optimal fashion?

The two were connected for a while - particularly where Newtonian science finally cashed out the deterministic simplicities of Ancient Greek atomism. Determinism, deduction and computation all go together as neat metaphysical package that appears to promise absolute certainty - something quite miraculous to humans more accustomed to thinking of the world as an arbitrary and uncertain place.

But we are beyond that now. The other side of the story is again more interesting.

apokrisis

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum