Comments

-

Poll: Evolution of consciousness by natural selection

It seems to me like the problem for the eliminitivist comes up in defining what metacognitive is supposed to mean here. For to say, "consciousness is an illusion cast by the processes of thinking about thinking," is not very helpful unless one already has clear idea of what "thinking is," and how to identify itin nature. Further, if we accept computational theories of mind, we'd have to ask when computation becomes thinking, since it seems clear that not all computation is thinking.

Perhaps elimination would be easier if theorists actually backed off "computation," as an explanatory model? The philosophical problems of defining what computation is vis-a-vis physical systems are myriad and daunting.

I like eliminative works for a few reasons. They do a good job cataloging the myriad ways in which "consciousness" is not what it seems to be, to us. Global workspace theories seem like they are on to something. But even if "to explain is to explain away," you still need to adequately explain first.

Where they fail is in being able to tell me why I shouldn't think then that an ant hive experiences consciousness, and more consciousness than the ants that make it up. Or why the FBI isn't more conscious than its individual members. Maybe it's prejudice, but these things don't seem like they should be conscious. And yet, if thinking emerges from really complex, really recursive, computation, markets, etc. seem like prime candidates for consciousness, Keyne's "animal spirits" vindicated.

This problem has made integrated information theory more palatable to me. It might seem to lead us towards panpsychism, but it also explains why you can't just replicate a brain scan with paper towels and get a "consciousness." Down to the very basic level, quantum effects and all, the paper towel brain is simply not a true replica of the brain. It is just a model of the course grained structure of the real brain, but the real brain itself is a very different process.

IDK, do any eliminitivists do IIT? All the one's I've read are CMT guys. IIT seems to attract pancomputationalists and pansemiosis folks, and these ideas, while they have some interesting things to say, seem to leave open the fact that everything is conscious. -

"Survival of the Fittest": Its meaning and its implications for our life

Whitehead's "The Function of Reason," deals with this, the distinction for individual living entities. It's the difference between "wanting to live," and "wanting to live well." Yet, I can't say Whitehead's ideas were particularly successful in biology writ large. There is still very much a wall between consideration of the intentionality that evolution appears to produce, and evolution as such.

And this might also explain why there is so much resistance to expanding the term "natural selection," to other phenomena, even lower level phenomena that doesn't involve intentionality. If natural selection, the process that appears to "lead to intentionality," were to be grounded in a sort of "universal process," instead of a suis generis one that occurs "by random chance," then it seems to open up the door to claims about "purpose as a trait of nature," and "universal purpose."

But my thoughts are:

A. So what?

B. It seems any claims about universal purpose would still be highly speculative, so why get so upset? The reaction seems like dogmatic policing. Further, if the universe is deterministic, then claims that it "inexorably gave rise to greater complexity, life, and goal directed behavior," are simply trivially true on first analysis (only eliminitivism seems to get around this). This certainly doesn't confirm Young Earth Creationism or make a case for not teaching evolution in schools however, so why the resistance?

C. If the universe produced us, and we have purposes, then nature already obviously does create purpose. In a rather straightforward way, plungers are for unclogging toilets, hearts are for pumping blood, etc. Any comprehensive theory of the world needs to explain these, not deny them. If hearts don't have a purpose in the way plungers or corporations do, we need to be able to explain the similarities and differences in terms of something we DO understand, not claim the difference is in presence or lack "of purpose," the very thing we want to understand. That's just circular, question begging, and dogmatic. -

Speculation: Eternalism and the Problem of EvilIf you're going to move back and forth across a time dimension to relive things in any sort of concrete order, such that you relive your life after you've first lived it, wouldn't that require another time dimension?

Well, we could always speculate about such a thing. -

"Survival of the Fittest": Its meaning and its implications for our lifeI don't think that "survival of the fittest," in its barest form, is unique to "life." You see it in the evolution of self reproducing silicone crystals and their response to shifts in the enviornment. You see it in lifeless bits of "organic" matter (such matter appears throughout the cosmos it seems, sans life). You can get DNA strands to solve Hamiltonian path problems through selectively tweaking the enviornment, but DNA strands alone are not "living."

And similar sorts of principles show up in what sort of matter sticks around in the universe. Maybe even in the way "more empty" vacuum tends to be more unstable, and so will tend towards spontaneously producing quark condensate.

I think the conception of biological evolution as necessarily this sort of suis generis thing is rooted in philosophical issues, soloing in the sciences, and the fact that evolution became THE battleground over religion and that this leads to confusion here. "Survival of the fittest," works well for all sorts of things we don't think of as living. -

Implications of Darwinian Theoryhttps://www.reuters.com/science/scientists-propose-sweeping-new-law-nature-expanding-evolution-2023-10-16/#:~:text=Titled%20the%20%22law%20of%20increasing,that%20generate%20many%20different%20configurations.

Sort of what I'd argued for before in other evolution threads. There are very many "selection-like processes." Some, like neural pruning, Hebbian fire together, wire together learning, etc. clearly involve purpose, some don't seem to. Biological evolution involves intentionality to the extent that intentional action affects reproduction. Further, if rocks don't think, dust doesn't think, etc. but life forms do think, then we might suppose that thinking emerges through these very sorts of processes, since they seem to be the source of growing complexity in the world.

It seems like fractal recurrence to me, similar information processes, occurring from nation-states down to crystal formation.

But if conciousness as we know it is something that emerges way down the line in these processes, no wonder it's not hard to find. It's an onion with a very large number of layers. -

The Book of Imperfect Knowledge

Interesting, I didn't totally catch that the first time.

To modify Hamlet a bit, "there is nothing true or false, thinking makes it so."

Well, I see nothing necessarily objectionable there. What could it mean for something to be true if falsity is not a possibility? But it also seems that states of affairs must precede knowledge of them. If I am to know I am mad, I have to be mad; if we are to discover a new superconductor, it needs to be able to act as a superconductor.

But notice that my reply deconstructs your Cartesian metaphysical assumptions

I'm not sure what's supposed to be Cartesian here? The idea that a rock and knowledge of "the rock" are not the same thing doesn't seem to necessitate anything like the mind/body dualism Descartes is most famous for. I was thinking in terms of the simple observation that our view of things depends on our perspective and that multiple subjects can have different experiences of what is, in some respect, the same thing.

So, we might say the truth of a thing is the whole, the grand total of all observations of it, all relations that obtain relevant to that thing. This doesn't require dualism, but rather precludes dualism. The unified whole is the truth, the partial revisions of the subject merely a part of the truth. The truth is the whole process, not any one "moment" of the process, e.g. my current conception of the truth of x at time t.

Rather than thinking these notions in terms of correspondence between subject and independently real objects, it defines the truth and the real on the basis of the ongoing success of our construals of the world in making sense of, predicting and ordering, in a harmonious and coherent way, the continually changing nature of the flow of new experience.

I'm with you on truth here, in that it is processed, but on the real? I'm not sure.

How do you deal with disagreements? When people first began to argue over whether or not the Earth revolves around the Sun or vice versa, surely there was, in some sense, a relationship between the two (Sun and Earth) that obtained before anyone was satisfied with their understanding of the matter? States of affairs aren't true or false, but we can later formulate descriptions of them that can be true or false.

If we were all solipsists, and did not believe in the truth of any experiences save our own, it seems there must still be a "truth of the matter." Either others would have experiences, and each solipsist would be wrong, or only one individual would have experiences, and that individual would be correct. Otherwise, it seems like there would be as many worlds as there are observers, and I'm not sure how such discrete worlds would come to be unified when one observer comes to "know" or believe that another's experience truly exist.

Maybe I'm misunderstanding something here, but it seems to go beyond dualism into a voluminous plural[l]ism. And yet, if each world exists, and they interact, then they are actually part of a whole.

Bedrock isn’t defined by what is independently ‘real’ in itself, apart from us, but by what makes sense to us in as harmonious a way as possible relative to our ways of construing the world. This bedrock of anticipatory understanding is an endless struggle, because the goal is nether out there in the world nor inside of us, but in the reciprocally re-adjusting coordination between the two.

How does this avoid the problem of multiple, sometimes contradictory truths? Or does it?

On the other hand, we generally settle for whatever guide for proceeding through life allows us to make sense of it in an open-endedly harmonious and robustly flexible way. And why shouldn’t we, since a flexible approach is a creative approach that has built into it the continual possibilities of self-reinvention?

Sure. But a partial and powerful motivator for the social endeavour that is "the search for truth," (science, philosophy, etc.) is that knowledge allows for causal mastery. And even though the correspondence idea of truth is in some ways deeply flawed (is science really a search for "truth?"), here it shows its pragmatic merit. The quest for the "true description," is tied up in the fact that knowing such a description shows you how you can edit it, the leverage points that exist for enacting an individual or collective will. I think this is sort of what your were getting at too.

Correspondence gets on well enough popularly because it does describe something deep about the world, that there is a difference between what we accept as true about the world and how the world reacts. But it's an incomplete description.

The reason most choose to wake up is that they buy into the matrix metaphysics of a Cartesian ‘real’ world. If reality is assumed to be some independent thing in itself, then surely our ‘simulated’ happiness is a cheap knock-off of the real thing, depriving us of a richer, deeper, more meaningful quality of experience. This is how most of is were taught to think about the real and the true. It doesn’t occur to us that experience is neither invented (simulation) nor discovered (empirically true reality), it an inextricable dance between the two.

I don't think the primary motivation has to do with "happiness," per say. The whole premise of the Experience Machine is the it will make you happy, and yet people turn it down. I suspect that people are skeptical of the Machine because it means being heavily determined by that which lies outside us. It lies outside us and we have no way to learn about it.

It's a lack of freedom then, not a lack of pleasure or happiness.

The fear is that, if the Machine is always working to guide us towards a happy state, towards pleasure, we won't develop or transcend. We cannot go past ourselves because the machine is posterior to our experiences.

But the sort of constant questioning you describe is what people want. I don't think it can be reduced to another desire in a straightforward way though. To question is to be going beyond what one already is, to go beyond current beliefs and desires, to transcend the current limits of the self.

In "The Dark Night of the Soul," Saint John of the Cross describes a period of purgation, where the senses are dulled and nothing brings joy to the soul. Event spiritual pursuits and contemplation no longer bring joy. Desire dies, sensuousness becomes muted. He describes it an an extreme "aridity."

This is an emptying, a letting go of all desire, and a letting goal of all concrete attachment to the sensuous world in preparation for the beatific vision, which is not one of pleasure, but of total oneness with all, through the One who is all.

That his work became a classic, and that similar guides are so popular among Sufis, in Zen, etc. bespeaks to me a sort of yearning for going beyond all desire, its own sort of desire, but a self-annihilating one. The machine is offensive to this drive because it seems to set limits on transcendence.

But I suspect some mystics might actually take the machine. If your life in the machine gives you more space for preparation, it can't hurt. It too can be transcended. -

Existential Dependency and Elemental ConstituencyAnd here is how we might consider the whole universe as absolutely simple: (something I've been trying to figure out how to phrase)

It is ever changing process, but (seemingly) of one substance. Everything seems to causally bleed into everything else, defining "absolute" boundaries seems impossible. Which atoms supervene on a candle flame? Where is the edge of the forest? Per Mandelbrot, what is the length of the English coastline? The further you zoom in, the more jagged outcroppings and microscopic bays appear, and the "length" stretches on an on.

Different discrete "things," "objects," might then be thought of as the result of perspective. They are not "unreal." Rocks and trees are plenty real, but they are also process not unchanging unity. Trees will grow, their boundaries ever changing, and then decompose and scatter. Rocks do the same on a longer time scale. Even protons undergo a life cycle, being born and undergoing decay.

The division of the one universal process into "parts" then is a question of "differences that make a difference," which are inheritly dependant on perspective from within the overall universal system.

For an enzyme, the presence of isotopes in a chemical reagent is generally irrelevant. In the context of the perspective of that reaction, the extra neutrons are a difference that fails to make a difference. And indeed, even with all their complex tools, diamond dealers would be unable to distinguish between two identical diamonds that varied only in the ratio of isotopes.

So the differences, information, is relational between subjectively defined (although not arbitrary) parts of the unified whole.

If fields permeate the entire universe, if, as Wilzek suggests, we think of space-time as a "metric field," and if unification, the "field of fields," is possible, then this unity is primary. An electron cannot exist prior to the EM field. Things cannot exist in space-time prior to the metric field. Quarks and the phenomena of QCD cannot preexist the universal fields involved therein.

But if course the cat or the apple tree does not precede the atoms that make them up. So it seems we might progress from the very small and the very large, meeting complex entities in the middle?

Or maybe only from the top down, on the idea that looking at smaller and smaller entities is simply to define our "area of universal process," into smaller and smaller slices.

What's interesting is that the history of any complex entity will cast a wider and wider causal net as we go backwards in time, as the "parts" get more diffuse in space and time while we move backwards. But in an absolute sense, the full causal history of entity has to go all the way back to the birth of the universe. Meaning the processes that "make them up," are always in some way connected. -

Existential Dependency and Elemental Constituency

You might be interested in Hegel's two Logics, which follow a somewhat similar methodology. But Hegel has the added criteria that we must start without any presuppositions, from a "blank slate." He thinks that dogmatically taking some things for granted will lead us into trouble. E.g. Kant takes for granted that experiences are of objects and ends up in a sort of subjective dualism by starting from this presupposition.

But Hegel's approach isn't so much about temporal priority, since to assume this relation is to assume time and causation off the bat, but rather "what pops up," if we start with as blank a slate as possible, "pure indeterminate being, sheer being."

The book is pretty brutal. I like Houlgate's commentary, it's a lot more straightforward.

But your apple example seems to assume two things:

1. Temporal ordering and causation. Is the dependence relation you're interested one of logical necessity or one of (physical?) causation? Or maybe the two are two sides of the same coin? I could see the argument that our logical sense emerges from the causal, as a form of abstraction that evolution equipped us with, but you can also see arguments for logic being more essential and "at work," in causation.

2. That "elemental" parts are, in ways, more fundemental that wholes. The elemental parts must exist before the wholes, no? But might we consider that the whole sometimes seems to precede the distinction of parts. E.g., we needed the universal process, the fields in which "part(icles) subsist" before we can have the elemental parts? Or, the universal relation through which "mass" emerges must pre-exist "massive particles," as the latter are necessarily defined in terms of the former.

Because it seems to me that you could also work backwards, in the opposite direction. The most general, "all being," is the most essential and simple. Things that "are," are dependant on this whole, and the finer grained "elements," are dependent on all that is "above them." Sort of the opposite of "smallism," a form of universalizing "largeism." Or maybe in, a mysterious way, both, dependence relations extending in both directions?

But I don't know if going in just one direction works, since parts are so often only defined in terms of their whole. This is especially true in terms of how heavily information theoretic approaches are used in physics.

A warm cup of coffee on a table tells us "someone made this recently, it is not at thermodynamic equilibrium, which it would be if it had sat here for a while." And yet that information only exists in the difference between the temperature of the cup and the ambient temperature of the room. Information is essentially relational.

Information, both as Shannon Entropy and Kolmogorov Complexity, needs the whole to be defined. And to the extent that information theory has really made itself a pillar of modern physics and major force in the philosophy of physics (e.g. It From Bit, ideas of information as ontologically basic, pancomputationalism, etc.), it seems more difficult to justify a purely reductive analysis.

The idea of the entire universe as a mathematical object, something you see in Tegmark and others, also seems to make the whole more primary. The elements are only elements because of what the set is, etc.

I might be misreading though. -

The Book of Imperfect KnowledgeHonestly, I'm surprised no one has proffered up: "if it tells you how to do everything you want and satisfies inquiry then it is telling you the truth." You could simply object to the supposition that it really lies to you.

I think you have nicely framed the core issue I wanted to get at. Does our inability to find truth, even in an approximate form — our being stuck "in illusion" — rob our lives of a sort of meaning?

In a twist on the "experience machine," a psychologist once told participants this story:

"You wake up in a lab, in a new body. The doctors tell you that you had voluntarily plugged into a machine that would simulate a life for you, a better life. All your friends and family, those are part of the simulation. They wake you up every 10 years and ask you if you are satisfied and if you want to go back, then wipe the memory of waking from your mind if you do go back."

The question is, do you wake up to the "real world," or go back.

Suprisingly, even in this version, which means leaving everything you know, most people chose to leave. If told that they were a rich, famous artist in their real life, only slightly more people choose the "real world," then if they are told nothing. If they are told they are a prisoner in a maximum security prison, fewer people choose to leave the machine, but a decent number, over a third if I recall correctly, want the "real" even in this case.

Of course, given such an experience, I'm afraid I'd have to always doubt that my "real world," is actually just another fake world. This is something Plato doesn't adequately address in the Republic IMO. Given we were mislead by the shadow puppets, then mistook the reflections for the things themselves, how do we ever know when we've reached bedrock?

But, per Hegel's more fallibilist system, maybe the point is in going beyond the given. In never settling. All questioning is itself, "moments in the Absolute," after all. -

The Independence of Reason and the Search for "The Good."

Sorry, I didn't mean to imply the Sam Harris, Hume, and Nietzsche all advance the same moral system. Obviously, they are quite different. I simply mean to point out that in Hume and Nietzsche, and in the naturalist position (Harris, Skinner, etc.) there is the same idea that "reason is a passion," or is rightly a "slave of the passions." They are very dissimilar otherwise. Nietzsche is pretty clear on his attitude towards scientific views of morality in the opening of BG&E, and it isn't positive.

The aim of the revaluation of all values is not to settle on some final or ultimate value system ( a higher good) but to stay in tune with the act of value posting itself as a means of not getting stuck in any particular value system. One could say that the ‘highest good’ is the continual movement from one normative conception of the good to another. Notice that this highest good is devoid of value content in itself.

Right, because there is no such highest good for Nietzsche; he accepts that as a truth. But my point was that, if Nietzsche had lived longer, and did indeed come to think he had found a higher good, he could no longer support his position. He'd have to disown a good deal of his philosophy. This is where it ties into Plato's point in the Republic.

That is, even if his system made him really happy, if reason then convinces him that it wasn't true, that there was indeed a higher good he had missed, then he'd want the higher good. He might feel conflicted about it, many philosophers have felt conflicted about having to abandon cherished positions, but there is a powerful way in which reason is able to bowl over and reorder all our desires.

A good example might be the person who loses their faith. Their highest goal was previously to please God. They organized their life around this, spending hours in prayer each day. And yet they no longer believe in God and so no longer think "pleasing God" is truly a good. Now, no matter how much all their other desires might want to lead them back into a "fool's paradise," here they are, in the crisis of faith.

The rest wasn't particularly relevant to Nietzsche in particular, just the idea of "reason as a desire"; I may not have made that clear.

Machines don’t produce value, they are devoid of meaning in themselves. What they achieve is only understandable by reference to meaningful desires and purposes that must be accessed independently of the meaninglessly calculative functioning of the machine in itself.

I wasn't totally sure what this has to do with the post. The machine is designed to fulfill desires. It doesn't need to produce values independently. It's value to us is that we can plug into it and be happy. But even if we are convinced that will fulfill all of our desires, reason might still tell us "no, it's wrong to do that." -

The Book of Imperfect Knowledge

Hmm, well, I didn't mean to exclude all forms of reading for entertainment. We could say that the Book also furnishes with tons of lovely fiction stories you will enjoy. Poetry books, etc. They won't correspond to the feelings any real author wants to express, but the prose will be excellent.

Ah, but does your current imperfect knowledge satisfy you? Aren't there some questions you're really itching to get a plausible answer on?

Of course, it's possible we wouldn't be satisfied with the answers of the book precisely because they aren't true. In which case it seems like we want to "know" and not just to have "know-how." The truth being its own sort of goal. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

Ya love to see it. :rofl:

Obviously, Sidney Powell, like Barr, Tillerson, McCain, Romney, McConnel, Mattis, Espers, Miley, etc. was always a deep state, RINO, plant embedded to try to sink Trump. How diabolical! -

The Independence of Reason and the Search for "The Good."

So one is driven by imagination, or by imaginary things. One can immediately see the shortcomings of the experience machine, which are the limitations of the imagination. Alas my imagination could never come up with a Bach fugue, or a Picasso, or a fine oak tree, or any of the wonders of my life, so a world limited to my desires would be a feeble shadow of the real world that consistently exceeds anything I could desire. So no experience machine for me, thanks.

:up: I really like that. Gets at the idea of going beyond the self better than I could phrase it too. The is a neat way in which interaction with things we could never imagine makes us free to imagine new things as well. A sort of "expanding horizon" that comes with experience and knowledge. -

Science is not "The Pursuit of Truth"If truth is just equivalent to "a complete description of what there is" then it seems to me that science is a search for truth. But under such a definition truth isn't bivalent.

Under such a definition, we approach truth as our description of the world gets more and more accurate. Thus, we could have multiple true descriptions of something like "how the Titanic sank," but some would provide a more full description than others. Full descriptions eliminate more possible worlds than less full descriptions. The fullest possible description eliminates all possible worlds except for the one that obtains.

Falsity would involve our descriptions eliminating real elements of the world from the set of possible worlds. To be false, a description must say that the set of possible worlds does not include (elements of) the world that actually obtains. So, if there was no widespread voter fraud in the US 2020 election, it would be false to claim that this occurred because such a description is consistent only with a set of possible worlds that does not include the actual world. But we could further say that something is more false when it eliminates more elements of the fullest possible description from the realm of possibility.

A full description might be something like "all you would need to simulate the universe." In an indeterminate universe, such a description might require infinite amounts of information if it is to include future events, but only a finite amount of information to describe all past events. And in this way, I think the definition might answer something about the truth value of statements about future events. The truth value of hypotheticals can be covered in a similar way, but it's more convoluted and beside the point anyhow. -

The Independence of Reason and the Search for "The Good."

Right, I don't think I had saved my edit yet before you posted. It is, in ways, similar to a desire. But for other desires, we desire what we do because of what we are and what we know. This desire to truth is a desire that seeks to go beyond what we are and what we know, a desire, in ways, to transcend the self. The desire for knowledge can have the effect of radically reshaping and reordering all our desires, particularly our second order desires.

This isn't true of all desire towards knowledge. Reason can be a slave to the passions, and often is. I might desire to know something to win an argument and feel vindicated, or desire knowledge so I can fix my car and go pick up chicken wings I am craving. But what Plato is talking about is the desire towards truth/the good because of what it is, and it's this desire that is transcendent. -

Science is not "The Pursuit of Truth"I've found it useful to divide the goals of science into two categories. You have knowledge/understanding of the natural world that we pursue to assuage our natural curiosity and to "make sense of the world." Then we have technology/mastery, the way in which science allows us to master cause and do things we otherwise wouldn't be free to do, e.g. fly across the world.

To distinguish these concepts in a word I figured gnosis/techne might work for easy labeling.

I would argue that techne tends to be what makes us think we've "gotten it right." If a theory enhances our causal powers such that we can do new and extraordinary things, then we are confident that our theories say something true about the world. There is a practical knowledge, "know-how," element to techne as well. Even though our theory of flight hasn't radically changed, we do continually improve the related techne for instance (e.g. thrust vectoring on the F-22, new control surfaces).

I see science as a core part of man's moral mission (to the extent we have one). Prudent judgement on policy requires gnosis and techne. Techne increases our ability to enhance all living things' well being, even if we don't use that information that way. Both make us more free. Further, gnosis seems to be a good in itself, something we enjoy for our own sake. It is a sort of transcendence, the ability to question and go beyond ourselves initial opinions, beliefs, and desires.

Just my $0.2. I think it's a mistake to separate science and technology as much as we tend do currently. Technological development, maintainance of old technology, etc. are all performative parts of the same entity. -

Ukraine Crisis

Russia is unable to widen the war without jumping up a nuclear option. They're fielding 40, 50, sometimes 60 year old unupdated hardware and rushing under strength formations that were promised they wouldn't be deployed until January (time to actually be trained and equipped) to stabilize the front. They are increasingly reliant on conscripts. They just had a coup that forced the government to flee the capital. They now have fewer tanks than Ukraine and are headed towards being behind them in artillery.

Fears of collapsing the Russian state if they are defeated to badly? Sure, that makes sense.

Fears that they are going to successfully invade Poland or something? That seems completely implausible. They can't even keep momentum in the current war they have.

Any doubt that NATO would have total air supremacy in a war with Russia was cleared up by the fact that the Ukrainian air force is still operating to this day. They were able to carry out enough SEAD with rigged up HARMS on old platforms they were never designed to work with to carry out CAS missions in Kherson. Russian AD, which proved so permeable in Syria to Israeli sorties (thousands a year for a decade straight without losing a pilot) has looked anemic here too on a larger scale. The pitiful response to the Wagner advance on Moscow was the definitive proof. If Russia tried to widen the war they would be comically outmatched.

They aren't even defending the Armenians, so there is obviously internal recognition of this. -

Ukraine Crisis

It's incredibly frustrating. Tanks and IFVs should have been provided from the outset. The F-16 should already be operating, and significantly more units of MLRS (although supplying munitions might be difficult, but they could have upped production). The "surge" in production for shells and artillery systems is also quite underwhelming.

If these had all been brought in before the summer, maybe with modern attack helicopters too, the war would very likely be over, or at least largely no longer in Ukraine's borders. -

Ukraine CrisisAnother major ATACSM taking out a large number of Russian helicopters. Given how these were instrumental in stopping Ukraine's abortive attempt at a "maneuver warfare," offensive, one wonders how much better it would have gone if these were provided earlier.

-

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankAnd people blaming Islamic Jihad seem off base to me, even if it was their rocket. Whatever you think of the group, munitions malfunctions and friendly fire happen. The US has carried out air strikes on British forces in recent decades. US rotary wing assets killed many Peshmerga in an infamous incident. And US planes carried out a prolonged attack on a US convoy early in the Iraq War. Israel infamously caused heavy damage to the USS Liberty. Ukrainian AD has caused losses in Ukraine. Such events are inevitable.

Even in peace time we've had things like an A-10 firing shells into a (thankfully unoccupied) middle school. People I know who flew in Blackhawks regularly still called them the "Crashhawk." War is chaotic. Explosives are dangerous even in a civilian workplace context. Negligence is bad, but one incident doesn't represent negligence. It more justified to complain if the problem is regular, e.g., Russia's shoot downs of its own aircraft in Ukraine seems like someone should be blamed, or the incident itself involves gross negligence (e.g. the Soviet shoot down of the Korean airliner where the pilot was extremely skeptical about firing and was ordered to anyhow). -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Right, and a large blast wave that extends beyond it. If this was a thermobaric weapon then it didn't work correctly. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

A thermobaric missile is highly unlikely to have light a vehicle on fire without breaking all the windows. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

I'm still hoping they don't decide to do this. The more I consider it, the less likely it seems like they can remove Hamas this way, -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

It would have to be a low yield antipersonnel weapon that is somehow mainly an incidiary. There was a large fireball and most of the damage seems to be from fire, which isn't what you'd expect from a high explosive weapon used to target infantry. I don't know if anything like that exists for the Hellfire, but there are old Vietnam era incidiary rockets.

[img]http://

You have cars quite close to the explosion in some aftermath videos with some cracked windows and some that are still fine. So it's a weird combo of lots of fire damage but weak blast damage. -

Perverse Desire

Hegelian perversion -- so I'd like to think -- is anarchy. Hegel's a funny ethical philosopher because he encompasses all values into a teleological order. So what could possibly be perverted, when everything has a time and a place? I put forward anarchy because I believe Hegel's vision of absolute freedom is the nation-state across the world. This would explain why there are Marxists, Liberals, and Fascists who all claim homage to Hegel: they all are politically dedicated to the nation-state. And the past, within Hegel, can be understood as slowly building towards the international order of states -- the maximum freedom -- but the modern anarchist is a perversion because they are against the telic order. On the whole I think perversion can be understood in each of the political traditions along this way: Marxists, Liberals, and Fascists each see one another as a perversion of their tradition, of the way a state ought to be structured. But for Hegel this is exactly what you'd predict and you'd be looking for the next sublation in the order of thought. But the anarchist sees no sublation, no telic order, no end. The anarchist simply doesn't want teleology or a state or a party. The anarchist demands freedom from teleology.

I always figured Hegel's commitment to the state had to do with the lack of any extra state powers during his era. He is still living in the shadow of Westphalia and the apocalyptic conflagration that killed a significantly larger share of the German population than both World Wars combined. The state was elevated out of fear of the return to religious wars.

But if Hegel had seen the failures of the state system in the World Wars, and moreover on climate change, global inequality, ocean acidification, recalcitrant multinational mega corps, and mass migration, I think he'd come around on the idea of things like the UN, EU, AU, etc. There is a tension in his philosophy. He wants to allow particularism, but then doesn't wholeheartedly embrace federalism because he wants the state to be an organic unity. I think this is a dynamic that plays out on many levels, individual vs society, region vs whole state, state vs union of states. Most philosophers focus on the individual vs society, I think Hegel is correct to also put emphasis on this higher level, even if he fails to totally resolve the issues.

I always took his point to be: "we are only fully free to explore our particularity in the organic, stable, harmonized whole," so in the end the two do support each other more than they contradict one another. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

If it was a Hellfire it would seem to have malfunction or it was some sort of very low yield variant I am unaware of. They do make a fully kinetic, very low radius version, but I'm not aware of any sort of low yield incendiary version that would be consistent with this damage. There are cars with still mostly intact windshields parked within what would probably be the lethal radius, or at least the wounding radius of a Hellfire.

The MAC is designed to pen buildings and then detonate so that the blast can be channeled through those spaces, so it'd be a weird choice for hitting the parking lot even if it did seem consistent, which it isn't for the reach of the damage.

The damage is way too small to be even an MK-82 500lb bomb, so a rocket or missile is the right idea though. But you're right that some weapons might leave a small crater and be more consistent. The most obvious thing I can think of is something like the small unguided rockets used in earlier decades, but then you would expect many to be fired and other areas to be hit.

And the video isn't particularly consistent with something like a 70mm rocket being fired. The folks the BBC contacted thought it was consistent with a failing rocket. I'm not expert on that, but it at least didn't seem to be the other explanations, an aircraft dumping flares or a fighter using its afterburner (for an incredibly short period, at like 3,000 feet, which also makes little sense). The flares would be lit up for longer, not shoot forwards and mostly go out as they fell at a fast rate (unless they were defective flares).

Old rocket pods can be used on the F-18, and if Ukrainian MiGs can be rigged up to fire HARMs, I assume the Israelis could have them set up on fixed wing craft (they don't fly the F-18). But why they would use them when they have such a hard time hitting their targets is another question. In any event, it would be more likely to come from a helicopter.

But if it's a weapon functioning as intended, it would have to be some sort of incendiary given the damage. If the goal was to kill people in the parking lot, this wouldn't make a lot of sense, and if the goal was to hit the hospital it would also make less sense. You'd have to sort of assume that Israel preselected a very different sort of weapon to hit this target than the ones they are currently using with the intent of deniability. I just don't see that when they are already leveling buildings with weapons they are quite obviously coming from their planes and doing a blockade that is plenty easy to condemn.

NGO's have given their opinion. The BBC, ABC, CNN, each had contacted panels of experts, although they are mostly Western firms staffed by former members of Western militaries, diplomatic corps, or intelligence services.

I haven't seen any that don't suggest that a failing rocket would be the most obvious cause, although not the only possible cause. But note that none of them have done a ground investigation yet.

It just seems to me that, if the argument is that "the Western defense agencies and NGOs will all go to bat for Israel," and if Israel's goal was "just to kill a lot of civilians," why wouldn't they use a more effective weapon? Why not just level the place with a real bomb and then say it was a munitions explosion, cook off from some accidental detonation? Or a defective rocket setting off cook off because "you know that Hamas, they love storing munitions near hospitals and schools?"

If you knew NGOs would lie for you, then you just attack. But I find it implausible that all the NGOs contacted are being dishonest since I've met plenty of former and current US security officials who are none too fond of Israel, and I don't think Israel thinks they can get away with that either. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

[img]http://https%3A%2F%2Fi.redd.it%2Fc1wndrip9zub1.jpg[/img]

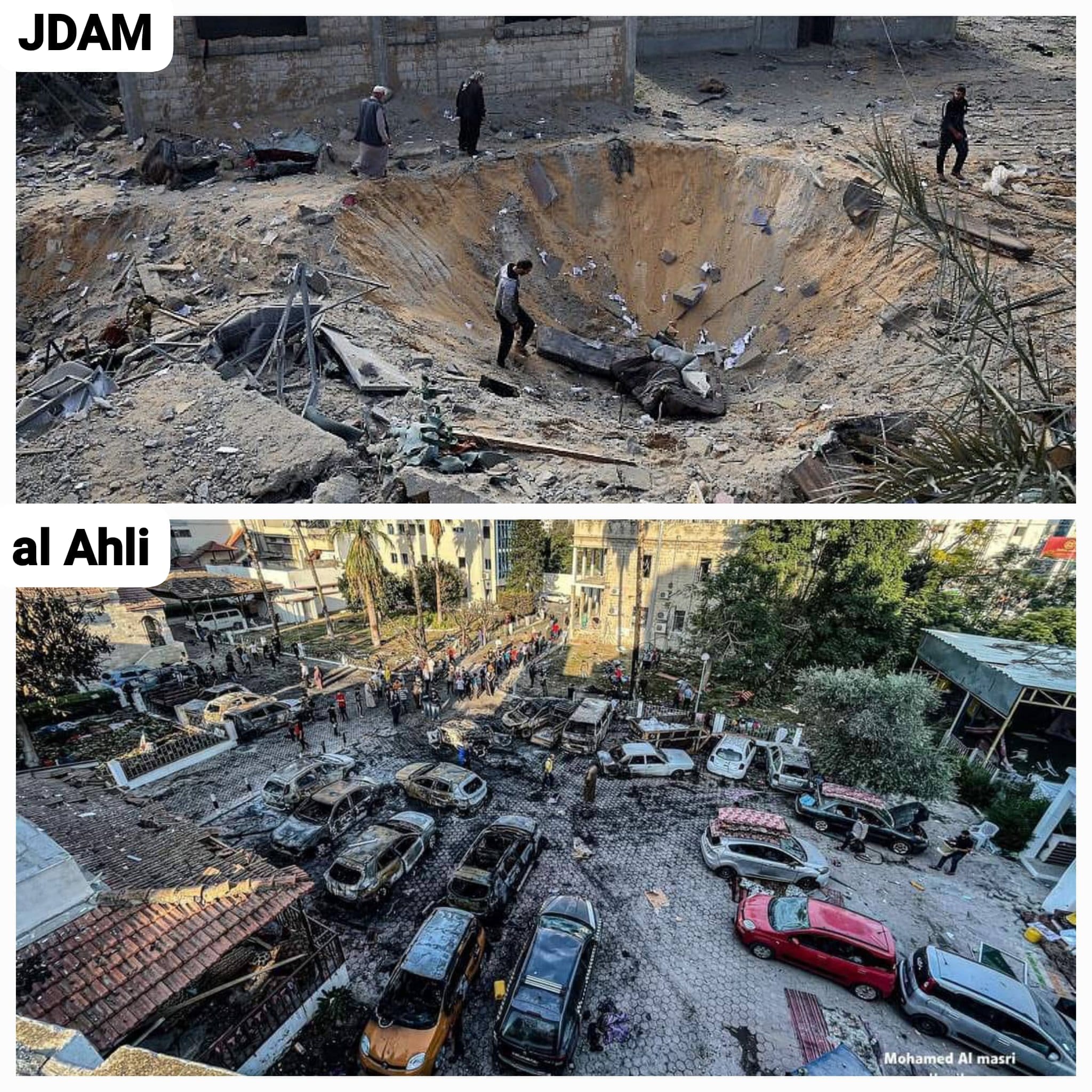

The pictures show extremely lack luster damage at the impact zone, almost no crater, and none of the concentric circles of damage you'd expect from an airburst bomb. Whatever it was, it was likely not a weapon that worked as intended. The most impacted area has a small crater and the cars are still in tact and in rows, neatly parked. Windows are blown out but there is no visible shrapnel damage.

The idea of it being a defective rocket is credible from that respect, because if it was even a 500lb JDAM you'd have much more damage. Or, alternatively, Israel air dropping some special low yield carbon fiber bomb that wouldn't leave material that could be traced back to them so they could blame it on a rocket. But that seems a little much, they don't really seem to have problems with letting the electricity run out, and that will kill more people. Maybe some sort of older rocket they have for their rotary wing craft, but I don't know why they'd even be using that in the first place.

I have to imagine the casualties are being vastly overstated unless the parking lot was packed with people.

By way of contrast:

A malfunctioning munitions impact isn't necessarily going to look like a functional one. If it still had fuel left and dumped it, that could explain the significant fire damage and scorch markets relative to shrapnel.

Or it might be consistent with some of the smaller unguided rockets like the Hydra 70, but those generally aren't used individually, in part because they rely on accuracy through volume. You'd be extremely lucky to get your target at night, in an urban enviornment, especially since I would assume they wouldn't be flying low.

Edit: and I guess there is video of what appears to be a failing rocket? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67144061 -

Freedom and Process

I shall expand.

Think about it like this. Does a "person" still exist in their body after they are dead? If not, what has changed? Their body is still largely the same. All the matter that makes up their body shortly after death might be a good deal closer to their recently living body than to the same person's body months prior. But if that's the case, then it seems its processes that are important in defining a person.

Place a body in vacuum and it will not produce any conciousness. It will be quite dead. So if corpses aren't persons, and I would argue they are not in an important sense, it seems a little hard to argue that persons are just bodies. Actually, placing a body into most of the conditions that prevail in most of the universe most of the time will not result in conscious, it will result in a corpse, or not even a corpse in many situations (e.g. a body close to any stars). Conciousness requires a continuous stream of interactions with the enviornment to exist and the contents of concious experience are also heavily determined by the environment.

If corpses are persons, when do they cease to be so? While deceased people might "live in on some way," presumably this can't be attributed to their bodies. But if persons are objects how can they vanish at death? And if they don't vanish, are all dead people floating around in bits and pieces everywhere?

Also, if I would be a "different person," if I was raised by different parents, in a different country, with a different culture, then it seems that part of what defines individual instances of personhood is deeply dependent on the enviornment. And how could it be otherwise? We don't develop the higher level cognitive functions that make humans unique if we are left locked alone in a room. Doing this will kill a child or at the least lead to profound cognitive impairment and brain damage.

We replace almost all the atoms in our body every few years. Do we become new people then? Maybe in some ways, but it also seems like people are in many ways "the same person," throughout their life time. In any event, this seems to make any sort of simple superveniance relation difficult.

It can't come down to simple structure, because our synapses are regularly "rewired," to a surprising degree.

Take other examples where boundaries seem hard to come by in defining a phenomena. What particles does a flame supervene on? It would appear that it's a different set every moment. Where is "the edge of the forest?" When it comes to some organisms, the line between species gets similarly blurry.

Take the microbiome. Is this part of the person?

Then we can get into all the sci-fi questions on this topic too.

For all these reasons, it doesn't seem to work to equate people directly with their bodies. The point is not that people "are" the things they interact with, but that the boundaries are necessarily blurry. Life seems to be best defined in terms of process, but it's a process with interaction points with the enviornment everywhere. So there is no clear separation.

Moreover, consider the way in which corpses don't appear to be persons and yet historical persons and dead friends and relatives do seem to be persons. We can easily talk of "dead philosophers," or "dead communists." Some aspects of personhood do seem to exist and persist apart from the body. It's easy to talk about "discovering more about x dead person's personality," or we can say "Robin Williams made me laugh yesterday," despite his being dead for many years. And in this way, the process associated with personhood, if not qualia, seems to spread fairly far.

It's prehaps less intuitive than the simple object view, but the object view seems to run into insurmountable problems IMHO. Bodies alone are necessary but not sufficient to cause conciousness. But how can a thing "be" that which is not sufficient to cause it to exist? -

Absolute nothingness is only impossible from the perspective of something

This is related to the reasoning that led Parmenides to deny to reality of change (and for Russell to do something similar millennia later).

Parmenides argued against Heraclitus that, far from everything being flux, change is not possible at all: in order for A to change into B, A would have to disappear into nothingness and B emerge out of nothingness. Nothingness does not exist, so change does not exist. The nothingness that Parmenides was denying perhaps has a contemporary parallel in the notion of the nothingness outside of the universe (vacuum is not nothingness in this sense). It is not clear that such a notion makes any sense, and this was roughly the Parmenidean point. Furthermore, for the ancient Greeks, to think about something or to refer to something was akin to pointing to it, and it is not possible to point at nothing. For a modern parallel to this, consider the difficulties that Russell or Fodor (and many others) have had accounting for representing nothing or something that is false

I think Hegel has an elegant solution here. We're here, so there is something. We have to start with that. So we try to strip that something down, to empty of it of all its contents and so arrive at a bare being in order to investigate what traits, if any, "something" must have. This is sheer immediacy, sheer being.

But what Hegel finds is that this sheer being is now totally contentless. It describes nothing, collapses into nothing. So, pure being turns out to be nothing. But nothing is itself unstable. We're thinking of it, so it's something, like you say. And so nothing turns out to collapse back into sheer being.

We have an oscillation, an unstable contradiction. But what if being subsumes/sublates nothing, incorporating parts of nothing into it? Then we reach the becoming of our world, where each moment of being is continually passing away into the nothing on non-being.

A better description of this can be found here: https://phil880.colinmclear.net/materials/readings/houlgate-being-commentary.pdf

And this makes sense to me from the perspective of what we can say about time. Why do we have a four dimensional manifold? Because we use the time dimension to mark when events have occurred. As Godel noted, eternalist responses to seeming "paradoxes" in relativity miss the mark. What can it mean to say "all times exist at all times?" Times exist at the point along the time dimension where they exist. Events occur when they occur. They do not occur at other times.

"Existence" is a complex word that leads to trouble here. When people say "all times exist" I think they generally want to say "all times are real." And this I agree with. But that doesn't mean that events don't occur (exist) at just the times that they exist. The time dimension becomes meaningless if it doesn't tell us when things occur. That becoming is local is confusing, and open to many interpretations, but also not all that relevant here.

Also I would quibble with this:

Absolute nothingness is most definitely impossible, but that is of no consequence. You see, absolute nothingness is only impossible if there is something to begin with.

This seems to beg the question somewhat. It assumes that nothing exists necessarily. If there are necessary things, then they exist by necessity, and they are something. Which would seem to entail for you that "absolute nothingness is [not] most definitely possible," if anything exists of necessity. And then of course, there are many arguments for things which do exist of necessity, although not all senses of "of necessity" have bearing here. We really mean "cannot not exist," in this sense.

There is a strong tradition of seeing the world as "blown into being by contradiction," by "the principle of explosion." If we start with absolutely basic necessary entities, say just sheer being, then we might still end up kicking off a cascade from there as contradictions are forced into progressive resolution. And in this way the universe would exist, but not really as a "brute fact," but rather of a sort of "logical" necessity, even though the starting point for the analysis is quite similar to the one that forces us to conclude it is a brute fact. It sort of hinges on necessity.

Could we say that, because there is now something, it is clear that nothing, by necessity cannot exist? Maybe. It seems no matter how broad you want to define existence, our very presence precludes that a "nothing from which nothing comes" could ever have been. This is for the trivial reason that there is something, and if there was only a "nothing from which nothing comes" there couldn't be a something. And so, from the basics of Augustine or Descartes' versions of the "cognito" we might be able to preclude the "nothing from which nothing comes," by necessity.

But is proving that nothing necessarily doesn't exist the same thing as proving the necessity of existence? Tricky. Perhaps we only prove the necessity of a bare something, sheer being. But then, according to Hegel, this is all we need to kick off the rest.

Of course. But "absolute nothingness" is mainly a pleonasm, it is redundant, as I explained above.

I see the value in it. We can distinguish "absolute nothing," from the "nothing" we find when we look for something in a bag and there is "nothing there," or when there is "nothing in my bank account." Then we also have the physical idea of vacuum to distinguish a philosophical "absence of everything," from.

There is also the internal "nothing," of life's lack of meaning or purpose. Or the "nothing" that underlies all values supposed in some philosophies.

As a Nominalist, rather than a Platonic Realist, that's my present understanding of the universe today, in that there are no such things as objects in the world outside the mind. What we perceive as a book only exists in the mind. What exists in the world outside the mind are elementary particles and elementary forces existing in time and space.

Aren't "elementary particles" objects? And wouldn't time and space be an object if it acts like a receptacle/container?

And if mind emerges from nature, from whence the objects of perception? The mind might "generate," perception to some degree, our "perceptual equipment," has a causal history, right? So what in the objectless world causes objects?

I agree with the denial of objects as fundemental, and the conception of Platonic forms as existing as some sort of super essential substance in their own realm, but it seems to me that forms have causal efficacy and that objects exist in the world, even if they are temporary, merely stabilities in a larger process. I don't even know if Plato really thought of his forms in the way they have come to be thought of. The way in which they are "higher," doesn't seem to track with our modern, substance dualism laced vision of Platonism. They are arguably merely higher by being more self-determining. They are "what they are because of what they are," in a way rocks and dogs are not. -

Freedom and Process

Yes. Although, if we defined "universe," as "everything that is," this would have to seem true in some sort of trivial sense. Maybe? I suppose maybe not, we could flip it around and say that the "universe is solely determined by what it is not," but this still sort of gets at a sort of self-determination.

Correct, but I think any "pure freedom," collapses into contradiction. Freedom must expand from "being able to do all things," to "being able to do what is in accordance with internal nature," or "everything one wants to do." From this sort of self-help philosophy combo boom I'm working on:

To start, let us try to conceive of “pure” or “absolute” freedom. What would this mean? If we are free it means, in part, that we are not constrained from doing something that we want to do. If we are "absolutely" free, we are free to do everything that we want to do, but also to do things that we do not want to do. An absolutely free entity can act in accordance with its nature, but it must also be free to act contrary to its nature, or even to change its nature. Elsewise, the entity's nature will itself be a form of constraint, a limit.

Let us imagine we have this sort of “pure freedom.” Imagine that we have before us an endless white plane, a blank sheet of paper with no edges. We are free to draw on it whatever shape we like.

But here, when we get to the action, we run into a contradiction. We cannot act and be free of all constraints. If we draw a triangle first, then we are not free to have drawn a circle first instead. If we draw something, then we are not free to have refused to draw anything.

Choice is its own form of constraint. What we see here is that, inherit to any positive decision, there is a form of limitation. We can not move up and down simultaneously. We cannot save our cake and have eaten it. We cannot draw a square and have our shape have anything other than four equal sides.

Thus, “pure freedom” requires the absence of any determinateness. We cannot do anything without in some way imposing a limit on what we have done. To choose A, B, and C, is to be unfree to have chosen just A and C, only A, or none of the above, etc.

But if we are only absolutely free when we flee from all definiteness then it seems that maintaining this “pure freedom,” would preclude our ability to choose anything! Yet, at the same time, if we are unable to make any choices, it would seem that this makes us completely unfree.

In this way, “pure freedom,” appears to collapse into its opposite. Our problem is not unlike the seeming contradiction that appears when we ask “can God create a stone that is so heavy that God cannot lift it?” This is because "omnipotence,” the ability to “do anything, without constraint,” implies a sort of “pure freedom” on first analysis.

So, have we disproven the possibility of freedom off the bat? No, rather we have shown that the concept of “freedom” cannot be reduced to “lack of constraint.” As we shall see, freedom is not simple. It is something that unfolds itself.

Self-determination occurs at a second level, after pure freedom as negated the lack of freedom it collapses into. Natures might be complex or simple, acting according to them requires a freedom with some positive elements.

I see it as a two part distinction. We have "positive freedom," the freedom to do what we want, and not other things, and then "authenticity," the freedom for our nature to be self-determining. I don't know if the move to authenticity is coherent for "the universe" though, and certainly the move to "social freedom," freedom between free individuals, doesn't seem to fit. -

Ukraine Crisis

Maybe if they say of the defensive instead of burning through hundreds of vehicles, tubes, and thousands of soldiers in attacks on entrenched positions. The fighting is a walkable distance from the pre-2022 borders, progress as been... slow to say the least.

With contract troops being chewed up on defense and them trending towards having less armor and less artillery, IDK. Conscripts work a lot better for sitting in trenches and defending when attacked, when they have to defend to live, then being forced to attack. -

Freedom and Process

I would base this supposition on the way the natural sciences, particularly physics, have increasingly done away with any concept of fundemental substances and the fact that everything in the natural world seems to interact with everything else. So it's not so much "fundemental inquiry," as "informed speculation."

Starting with parts and building up towards a whole assumes that the whole can be defined by its parts rather than vice versa. But arguably "fundemental particles," can only be defined in terms of the whole, the field, etc. It's unclear if the smallest is the simplist re the natural world. The hopes of a unified physics sort of assume that this is not the case, that the grand rules of the whole can be "written on a T shirt," as Tegmark puts it, while the intricacies of parts like bacteria and trees could take centuries longer to understand.

Well yes, it's a big supposition to say that the universe's properties are solely due to "what it is," and that it "has no external cause." But since this seems like a different can of worms, I figured I'd assume that universal laws aren't actually extra-universal (supernatural?) causal entities. That conception has fallen out of style at least, although I know it's still quite defendable. But if we accept that physical regularities occur because of "what the universe is," then it would seem like it is self-determining. Even if it is created by a prime mover, it would still seem to remain self-determining in some key respects. -

Freedom and Process

Not sure exactly what you mean here. It seems to me that people are autonomous, just not completely so. Babies don't raise themselves, we can breath without oxygen, etc.

I don't see the ideas here as being necessarily "impersonalist." Conciousness arises from process. All process is ultimately interconnected, but we can still identify long term stabilities in process that account for different entities, and some entities are concious. When mystics talk about "oneness," they seem to be talking about something deeply personal. More "the universe in me," than the "me in the universe."

I suppose a core idea I wanted to get at was that this explains how our freedom as individuals can be so interconnected; how our fellow humans can empower or frustrate our efforts to be free.

That and the simple idea that process metaphysics seems to allow for strong emergence and relative self-determination. -

Ukraine CrisisThe Russian losses at Avdiivka are grim. And yet another "deadline" has been set to secure the Donbas. I don't see how Russia's ability for offensive operations can recover, and yet clearly the calculus is that "more must be taken to make it worth it."

-

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankIsrael seems to be backing off on (much of) a ground incursion. I am not sure if the mobilization was done out of panic, as a political move, or to force Hamas to expose itself by building fighting positions, thus making their forces easier to ID and strike from the air.

Ground raids have occured, with a large weapons cache being displayed earlier. If the air war is effective, that could be another reason to let up. That or I can see why an invasion wouldn't occur until goals are defined. One goal I can think of is the elimination and suppression of Hamas, followed by the return of Palestinian Authority rule to Gaza. This could open the door to new funding for economic development from the Gulf, as Iran would no longer "hold sway," over the territory.

But would Fatah even be credible if it was brought back in this way? It has its own image problems. And Abu Mazen is quite old. What happens when he dies? But, that said, if there was a center left government in Israel after this and Fatah as the one bargaining power, it does seem like a deal for statehood and peace becomes far more likely.

Or it could simply be indecision. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

At least the Likud is also very popular in Israel. Benjamin Netanyahu has been the most successful Israeli Prime Minister ever and is the longest serving one. Isn't it the third time he's in office?

It isn't though. It needed an alliance with Haredim parties to eek out a government. You need 61 seats and they have 64 in their alliance. But then they tried to use this narrow majority to drastically change the Israeli courts, precipitating a "constitutional crisis" of sorts. That's partly why Israel was so vulnerable to this attack.

Support for Likud has absolutely imploded. Polls show them winning a bit over half the seats they currently hold. Netanyahu compromised some core values for the current alliance, in part it seems, because he wants to hold office to avoid prosecution for corruption charges. In any event, post attack his approval rating has tanked to 29%. Gantz is up 20+ points on him now. It seems like, when the crisis is over, the centrist and liberal alliance is going to absolutely sweep. You can't campaign on strength and then deliver the worst attacks in decades. And unlike Bush during 9/11, this is clearly the fruit of Netanyahu's own policies as he's had ample time to shape Israeli security policy. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Terrorist organizations can and do become responsible governing parties. The Israeli state itself emerged, in part, from terror organizations. You can see the same thing in many places. The problem isn't that Hamas can't make this change. Really, Hamas did sort of look more open to compromise before their violent take over of Gaza. And the West and Israel should have been more open to them, but the whole Post-9/11, "communists now ok, Jihadis bad," mindset stopped that.

But it's also not like Hamas ever moved particularly far in that direction. If anything, the past 8 years or so they have become more and more tied to Iran and their prerogatives, making them a less trustworthy partner. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Not that I've heard. And there are also a lot of foreign nationals in Gaza who want to get out as well. Both hostages and foreigners are likely to cross into Egypt for an exchange, but no one is being let out.

It is very unclear what is happening at the border. It remains sealed. Egypt has variously said Hamas is blocking to border and that an Israeli strike is what has sealed the border and they can't repair it. The strike narrative seems less plausible as time goes on and there is more time to clear a path. Plus, Israel seems to want to opposite to happen, for the border to be opened, so this seems dubious.

According to an NPR correspondent, Hamas has sealed their side of the border.

According to some source from CNN, Egypt has laid concrete barriers across their side of the border and Hamas is not allowing people to leave anyhow.

According to Israel, Hamas is not allowing people to evacuate the south on pain of not being allowed back, which is dubious given the source, but could turn out to be true.

Egypt has pulled out the "if they leave now they will be dispossessed so they must stay," line after going back and forth.

It's totally unclear what is going on. Israel's allies seem to be advocating for the border to opened which makes me think Israel does want the border open. It's obvious though why Hamas would not want an evacuation, both on a tactical and strategic level, even if it is the height of cynicism to trap people there.

But then that's just the situation that exists today. All settlers were forced out of Gaza by the IDF. Hamas administers Gaza. The question of Gaza being an open air prison is entirely about how much and what type of traffic Egypt and Israel allow through their borders. And both have some justification for constricting traffic to and from a state with open support for terrorism in their borders.

But the problem has become much more complicated. After the decoupling of the Gaza economy migrants moved to Israel and took those jobs. There is no returning to 1990 where Gazans at least benefit from the prosperity across the border I

some way, because residents from Thailand and Eastern Europe have taken those jobs. And this takes away a major bonus of Gazans, if not Hamas, in normalization. It's moved peace further away because the dividends peace would pay out have been much reduced. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

No, I was referring to Libya, where Gaddafi was calling for all the Arab countries to expell their Palestinians too, since obviously by accepting negotiations on independence they were giving up on absolute victory and thus betraying "the cause."

Kuwait also expelled 400,000+ Palestinians in the 90s. In Lebanon, there was ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, although this was in the context of the broader civil war and Palestinian massacres of Lebanese civilians as well, making it less one sided.

Egypt just denied their Palestinians basic rights and refused to accept them back after a war they precipitated ended up with them behind an Israeli truce line during a week of fighting. There was bargaining over this, but Egypt not taking back the people they had ostensibly annexed Gaza "on behalf of" was a major sticking point for Egypt. -

The Hiroshima Question

Ah yes, the Samurai soul of beheading prisoners, and having thousands of civilians committ suicide for no reason.

Much like people lamenting the death of the "Crusader spirit," of the Middle Ages and the European Wars of Religion lol.

Count Timothy von Icarus

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum