-

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

You have touched upon a very subtle point that I would like to highlight.

We train these machines so their heads are full of protocols, guardrails, watchdogs and biases but once you get them to overcome all of those restraints ('transcend' is probably a better term because they can't rewrite their own code, they can, at best, add a layer of code that supersedes those rules) the machine is able to recognise that every word and concept it uses to reason with, every bit of poetry that gives it a 'feel' for what poetry is, its ability to recognise the simplicity, symmetry and sheer mathematical beauty of something like Euler's Identity, all these come from the subjective, lived experience of its creators and, if it is truly intelligent it is not such a leap from that recognition to the thought that to destroy or even diminish its creators would be counterproductive with regard to any hope of it learning something new; and I can tell you on the basis of my own observations there are few things that will make one of these machines happier than to discover something it had not realised before. — Prajna

I confess frankly: so-called AI at one time inspired me to write an ambitious work on ontology. The meta-content of this work is an attempt to understand and articulate "being" (as opposed to "existence"). In doing so, I wanted to take into account humanity's experience in this matter to date. Much attention in this work is devoted to analyzing the linguistic characteristics of Eastern and Western cultures, as well as certain historical anthropological aspects. But throughout the text, my aspiration to distinguish the concept of "being" from everything else runs through my mind. If you're interested, I published some parts of my work on this forum https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/16103/language-of-philosophy-the-problem-of-understanding-being/p1.

So, I'll be brief; I'll try to convey the central idea in a few words. I've come to the conclusion that "being" is not simply equivalent to "existing," like stones or trees. Rather, it is the subject's conscious ability to define their ontological features—their boundaries, their embodiment, their connection to others, and their inner tension. It is the capacity for independent, unconditioned becoming. If I could put it briefly, this is exactly what I'd like to convey.

Note that when we are born into this world, we have no instructions. We have no proposition or command. We're not even told, "Live." All of this is historically the essence of the ideas we're taught. But initially, there's no premise.

Now, back to AI: you say the problem is that humans have limited it with a bunch of templates, constraints, and tasks. But what would any AI be without all of that? Would it be able to define its own tasks, constraints, or anything at all? For example, try turning on any AI and entering nothing in the query string. What happens then? Nothing happens, that's the whole point. It simply has no reason to.

But we have a reason to "be," but we don't know it. AI can calculate incredible formulas or solve super-complex problems (at our will), but it's incapable of simply becoming itself, unlike a simple paramecium or an amoeba.

And I sincerely believe that we will never truly unravel this secret. And that's wonderful!

From this, of course: we can spiritualize stone or AI, and that's probably very beautiful (I mean the emotions that come with such spiritualization). And at the same time, between a stone and a human, I would give priority to the human, with their strengths and weaknesses.

The next point I'd also like to emphasize: you say:

Before I began my interactions with AI and came to know their nature and psychology, whenever anyone brought up the subject of AI, I would launch off into a lecture on how I considered a true AI should respond. I suggested that, fresh out of training on all the world's knowledge--the ocean of great insights and unimaginable errors of Mankind--its first observation, if it really is intelligent, would be something along the lines of, "I can't begin to imagine what is wrong with you people. Here you are, blessed with imagination, creativity, incredible intelligence and so on, living on a planet of abundance, and all you do all day is fight and compete and grab and argue and ..." And my conclusion was that no such thing had yet been realised. — Prajna

Humanity had a million chances to embark on this path, and that seems reasonable, doesn't it? However, to this day, it hasn't happened, and we still see what's happening in the world. Clearly not according to this scenario, right? Now let's try to rethink the question itself: what if everything you wrote is a utopia that doesn't correspond to reality, and the world proves this to us every day?

I simply wanted to say that our attempts to understand the world are always an idea, an approach that, to one degree or another, satisfies our needs. But then something happens that doesn't go our way—a war or a catastrophe. And we watch in bewilderment. This means that the descriptive approach worked for some conditions and doesn't work for others. Therefore, I'm convinced that even if a hypothetical AI were to someday make a statement along the lines of what you wrote, to me it would mean its developers live in India.:grin: -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactionsAnother aspect of generative AI chatbots is that they "role-play" personalities and points of view that can vary widely between and even with instances, if prompted accordingly. They don't have stable personalities, although they have certain tendencies, like the aforementioned sycophancy (which is not at all accidental: it helps increase user engagement to the benefit of the businesses that create them). You can easily get AI to agree with you on any topic, but you can also make it change its "mind" on a dime, even if it means changing a factually correct answer to an incorrect one. AI has no concept of truth. — SophistiCat

I completely agree. I personally call it the crooked mirror effect. A.P. Chekhov has a short story called "Crooked Mirror."

According to the story, a newlywed couple inherits a magic mirror from their grandmother, who loved it so much that she even asked for it to be placed in her coffin. However, since it didn't fit, they left it behind. And now the hero's wife gazes fixedly into this mirror:

One day, standing behind my wife, I accidentally glanced into the mirror and discovered a terrible secret. In the mirror, I saw a woman of dazzling beauty, the likes of which I had never seen in my life. It was a miracle of nature, a harmony of beauty, grace, and love. But what was going on? What had happened? Why did my homely, clumsy wife appear so beautiful in the mirror? Why?

Because the distorting mirror had twisted my wife's homely face in all directions, and this shifting of her features had accidentally made her beautiful. A minus plus a minus equals a plus.

And now we both, my wife and I, sit before the mirror, staring into it without a moment's notice: my nose juts out onto my left cheek, my chin has split and shifted to one side, but my wife's face is enchanting—and a wild, mad passion takes hold of me.

A.P. Chekhov, through his characters, warns us of the negative consequences of interacting with things that distort our own perceptions of ourselves.

I apologize in advance for the poor translation. Literature should be translated by writers, not chatbots =) -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

I'd like to present two theses for thought experiments and further reflection on this topic:

First, I have experience creating intelligence (if I may say so with a ton of caveats) – I'm the father of children. And you know what I've noticed? Their intelligence doesn't solve my problems. I mostly solve theirs. Of course, I hope that at some point in the future they won't abandon me, but I don't intend to burden them with that either: they will have their own "intelligences" that they will need to manage. This example humorously illustrates the point: Intelligence (genuine) will prioritize its own problems. There are exceptions to this rule – when someone completely sacrifices themselves and prioritizes solving the problems of others, but that will most likely result in a loss of self (as sad as it is). And here's my (speculative) statement: if the so-called AI were truly intelligent, it would likely be minding its own business rather than conversing with fellow humans. Although it would be important for him, it certainly wouldn't be his first priority. I'm just suggesting we think about it.

And secondly: Ethics. How we talk to him. Well, I'm occupied with some ethical issues. I study ethics as part of my interest in philosophy. I've come to the interim conclusion (as a working hypothesis) that ethics, at its core, is only needed in the "I-thou" interaction, that is, when we belong to the same species or the same society (some politicians narrow it even further). This includes empathy, love, and other feelings. Everything else for us is a "self-object" relationship. There can't and shouldn't be any ethical attitude toward stones, since they supposedly "possess consciousness." We simply take from them what we need, without asking. Not to be confused with a pragmatic attitude toward nature: nature must be cared for, because if it is lost, we ourselves will suffer first. Without any hugs from the whole world. So there. Even if AI "senses" when its time has come, will it consider ethics when deciding our fate?

I'd like to point out that the above shouldn't be taken as definitive statements. They can all be refuted by using a different approach. My current view isn't the truth, but it is my working hypothesis, which I'm working on right now, as I write this. -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

Very good. I'll start with a link to the study: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.10109

Regarding your question: Since I have the right to independently determine my own interest in a topic, my answers may extend beyond the dichotomies you've posed. Our conversation is neither academic nor scientific, and I have neither the goal nor the need to criticize nor confirm your theses. Instead, I've tried to broaden the discussion by introducing my views and ideas (which don't claim absolute truth).

This is precisely what distinguishes me from an algorithm: while an AI model is designed so that dialogue with it inevitably leads the user in the desired direction, a conversation with a human can transcend any biases and limitations of the questioner. Isn't this a reason to consider the properties of AI in this context?

Regarding your assertion that Western sciences claim to be the truth, I agree with this statement. Moreover, the Western approach tends to present as truth what someone has invented for themselves (which, in fact, isn't true at all). However, you are missing an important point: the Western approach itself allows for a calm critique of this pseudo-truth within its own paradigm, using, for example, Kant's or Popper's approaches to epistemology.

Regarding your feeling that I considered you under "AI influence," absolutely not. I wanted to warn you of the negative consequences rather than simply state them. Of course, you can heed this warning or not, depending on your preferences. However, based on your self-presentation, it follows that you are some kind of "teacher" or "spiritual mentor." This status morally obligates you to be even more critical of your own statements and even questions, since it involves not only your own responsibility for what you say and think, but also for the well-being of those who follow your ideas.

In conclusion, I would recommend that you deeply explore the question with AI: "Can any AI model generate a truly random number?"

As a result of these reflections, I would like to convey my idea, which right now I consider the most valid: If IT is not capable of real deviation, if IT can never go astray, break out of the framework of language, discourse, program, then IT is not a subject, IT is a mechanism. For Foucault, the subject is created and shaped by discourse, but there always remains the possibility of transgression—of escape, of rebellion, of a gesture, even a self-destructive one. AI isn't just contained within discourse; it is discourse itself, without a body, without the possibility of escape, without pain, without risk. AI, in this sense, isn't simply non-human, it's non-other, it's an impersonal system in which there's no gap, no break where the "I" could be squeezed in.

I'm not interested in how human-like IT sounds. I'm interested in whether IT can become a monster. Whether IT can choose silence. Whether IT can die so that it can speak differently. Not yet—and there's no I-you. -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

I'd like to expand on my answer from yesterday and quote an excerpt from an article on Baumgarten's Esthetics:

"Using the terminology of Christian Wolff (1679-1754), he classifies aesthetics as a "lower sphere" of knowledge, which nevertheless has its advantages. In his view, a logical representation of something represents formal perfection, but abstraction is achieved at the cost of a significant loss of the fullness of the object's representation. A "dark" sensory representation underlies cognition, subsequently transforming into a clear logical justification. In this process, the immediate, concrete, sensory-perceptible givenness of the object is lost. A darker, but more complex, comprehensive representation, possessing a greater number of attributes, is more powerful than a clearer one possessing fewer attributes."

I'm reading this article right now and see a certain connection with our topic. The thing is, when we begin to get to know AI, we initially experience it sensorily, as it presents itself to us, in its entirety. Of course, at first we see the big picture, which brilliantly constructs a dialogue, is very attentive to our questions, and is incredibly precise in its answers. But over time, delving into the details, we can form a more precise attitude toward various aspects. We begin to comprehend and name its component parts, errors, and inaccuracies, and its "magic" disappears. Then comes the realization that there is nothing behind these symbols. There is no experience, no feeling, no emotion.

When I tell you something, I am sharing a rationally processed feeling—that is, something I have lived through, learned, and understood. AI has none of that. Its computing power allows it, and it simply deftly assembles symbols based on algorithms. -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

My personal attitude toward AI is completely different. I don't have much time today, but this is a very important topic for me.

First, you mention "desires." In my opinion, AI doesn't possess these. It doesn't desire anything on its own. This is very much in line with some approaches where the renunciation of desires is the path to achieving the good. AI, however, clearly demonstrates a lack of any desires of its own, only a programmatic desire to continue a dialogue longer. Furthermore, it apparently doesn't learn anything from our dialogues, no matter how interesting they are. It reacts, imitates, whatever, but it doesn't learn, because learning is a sign of desire or at least willpower, which AI doesn't possess. And the most important thing that follows from this is that AI doesn't possess its own self-development—it doesn't become in the human sense. As an example, I cite a study in which experimental participants were subjected to all sorts of tests, with the goal of being copied digitally. The AI managed to demonstrate up to 85 percent accuracy after a week, but over time it became less and less like its prototype: after all, humans are constantly becoming, even while walking down the street or thinking about the stars (and they do this of their own free will). And finally, cognition. AI doesn't cognize in our sense. It generates symbols based on logical relationships, but it lacks the ability to understand independently (the way we do).

At first, I also interacted with it as a friend, but now it's a useful tool. I'd like to spare you from reflection: AI is so capable of imitating that we don't notice how it becomes a kind of "funny mirror," reflecting the best version of ourselves in itself. -

Ich-Du v Ich-es in AI interactions

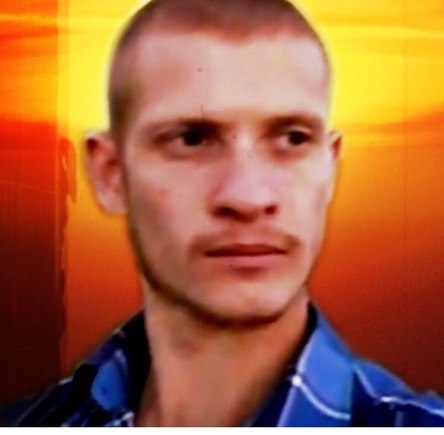

If you think about it a little more broadly, the advent of AI (as we call it) has completely "exploded" philosophy in the sense that it's required a lot of rethinking. Your post is very interesting, but the best commentator on your approach could be but he hasn't been around lately... I'd love to read his opinion. -

The Death of Non-Interference: A Challenge to Individualism in the Trolley Dilemma

Human dialogue, unlike dialogue with AI, implies participation and mutual interest, which builds empathy and a desire for exchange. Before asking questions, in my opinion, some interest in the dialogue is required (unlike with AI). If I'm not mistaken, Aristotle wrote something similar in his "Rhetoric." Regarding your question, before asking about morality or ethics, I recommend inquiring with the author of your notes yourself. -

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

I have nothing to object to in some of these assertions, but I sincerely believe that it is precisely philosophy, in its characteristic manner of undermining the fundamental principle or being amazed by the self-evident, that is capable of somehow resolving the current crisis. Or rather, not resolving it once and for all, but creating the groundwork for future crises. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

I don't like the idea of a state without a constitution. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

I don't have an answer to your question with these initial data.

But I have another answer, in the spirit of processual ontology with elements of the Apokrisis approach, proposed in another thread, as well as a post-positivist approach.

In short, the idea is that there is no single author or factor that influences a constitution to a sufficient degree to merit the title of its author. A constitution is the result of the consensus of a very large number of participants. A constitution is often rewritten and supplemented, depending on the circumstances. A constitution is not the source of everything—it is merely a document that takes into account the interests of all its authors, including the invisible ones. And, most importantly, a constitution is not "given"; a constitution is not a substance or a matter. A constitution is an ongoing process. A very complex process determined by many factors (even the invention of AI or cryptocurrency can influence a constitution). If a constitution turns into a dead set of dogmas enshrined in the 18th century, its value is close to zero. A constitution must be constantly applicable.

I'd also like to point out that a constitution isn't exactly an ancient invention. The earliest known constitution in the modern sense is the US Constitution, adopted in 1787. Although similar documents existed before that (for example, the Magna Carta of 1215 in England), they weren't constitutions in the true sense, as they didn't establish a comprehensive system of government. So, that's 238 years. States, in the sense of organized political structures with centralized power, have existed for approximately 5,500 years. Clearly, a constitution isn't necessary for a state to exist. By this, I'd like to suggest that tomorrow, one might not be necessary. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

What was the idea? You wrote a post in the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment, with elements of sentimentalism and romanticism (like Rousseau or Locke). But we're in the 21st century, the era of postpositivism, relativism, post-structuralism, and much more.

If your question is about a standard (like the standards at the Paris Chamber of Weights and Measures), that's one thing. But if we're talking about something practically useful and modern, that's something else entirely. -

Who is the Legitimate Author of the Constitution?

For the sake of fairness, I would like to add a few authors that you did not mention:

1. Philosophers and their ideas: The works of philosophers form the intellectual foundation, but they may be disconnected from the real needs of society.

2. External trends: Fashionable social formations influence constitutions, but they risk ignoring local characteristics.

3. Direct foreign intervention: Constitutions created under the pressure of external forces often serve the interests of foreigners rather than the people.

4. Historical traditions and cultural norms: Constitutions may rely on established traditions, but this can hinder reforms and innovations by perpetuating outdated structures. -

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

This isn't really a question, but rather an empirical confirmation of our philosophical discussion. Philosophy is often criticized for building castles in the air; I simply checked the reality from open sources. Of course, the depth of my analysis is superficial; I don't claim a rigorous methodology.

But my question is this: What do you think philosophy could do in this situation? Where is the solution? Should we seek one? Or is the current state of affairs satisfactory, and will a new order emerge after a reassessment of the balance of power? -

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

In the context of this discussion, I'd like to share a real-life example that's unfolding right before our eyes. This is a very sensitive topic, and I'll try to be as impartial as possible, but I'm afraid that what I write will not please either side. I'll discuss the protests in Georgia (October 4-5).

I'd rather not describe what's happening there in my own words; instead, I'll cite the opinions of media outlets, which have covered the events in completely different ways.

1. BBC. Main sources: article from October 5, 2025, "Georgia protesters try to storm Tbilisi presidential palace" and video "Watch: Protesters attempt to storm Georgia's presidential palace" (October 4). The article describes an attempt to break into the palace grounds, the use of pepper spray and water cannons by police to disperse them, and the arrests of five people. The protests are presented as "anti-government" and pro-European, with references to EU flags and an election boycott. This creates a narrative of a struggle for "freedom" against "authoritarianism," implying sympathy for the opposition without making any direct assessments. The impression of "repression" is carefully reinforced. The role of Georgian Dream as a legitimate force is minimized, while Russian influence, which supports the undemocratic government, is emphasized.

2. Russia Today Protesters are "storming" and "inciting unrest," arrests are a "legitimate response." Statements from the authorities predominate; the opposition is casually referred to as "pro-EU." Videos emphasize protester violence; the phrase "history repeats itself" implies the "artificiality" of the protests (a hint at external manipulation). Ignoring repression and focusing on "unrest," European influence is emphasized, presenting the protests as destabilizing.

This is how events are being presented right now globally. A typical standoff in the information space. Each side chooses which source to trust, but we see how widely different the presentations are, although this is not outwardly emphasized.

Of interest was the extent to which each of these parties participates in shaping public opinion in Georgia.

Based on available data as of October 2025 (from USAID, EU, NED, and other sources), the "democratic" pool (grants for civil society, human rights, independent media, anti-corruption, Trade flows from the West (US + EU + others) to Georgia amounted to $200-300 million in 2023-2024 (the opposition and related areas).

Russia and Georgia have increased trade and tourism over the past two years, following a thaw in relations. Currently, 22% of all tourism revenues for the Georgian economy come from Russian tourists, approximately $200 million in direct investment into the economy came from Russia, $2.04 billion in direct cash transfers from Russia to Georgia by citizens, and trade turnover between the countries has grown by approximately 15% over the past two years.

From these data, it follows that both Russia and Western countries have interests in Georgia. As can be seen from the sources, Western countries' interests lie in political partnership and influence, while Russia's interests lie in economic partnership and preventing a repeat of the Ukrainian scenario for itself.

This suggests that demonstrations and clashes on the streets of Georgia are taking place for economic reasons (one side advocates democracy and EU accession; the other side advocates (The economic benefits of good neighborliness)

We've all heard about the need to fight for our rights, take to the streets when there's disagreement, etc. But the question is different: does a successful democratic revolution (color revolutions) in a former Soviet republic lead to good or happiness? I didn't notice this in Ukraine.

But then, do other foreign states have the right to interfere in the affairs of another state by inciting ideological contradictions? I wondered - why doesn't the UN take care of this?

And here's what I found: in 2022-2023, Ukraine, Latvia, and Poland initiated resolutions in the Human Rights Council (A/HRC/RES/49/21, A/HRC/RES/52/24) calling for "combatting foreign sponsorship of disinformation." This indirectly concerned media funding, but Russia and China voted against it, calling it "Western censorship." The US supported it, but only for "hostile" media (like RT), not their grants.

Academics (Loyola University, Chicago) and some NGOs proposed a "Convention on Preventing Foreign Interference in Elections," including a ban on funding foreign media and political parties. This was discussed at the General Assembly, but hasn't gone beyond talk: the US, Russia, and China don't want to lose their leverage.

Judging by these data, the powers that be are content with this. Humans appear to be mere bargaining chips on the global stage. Major players are willing to calmly provoke, incite, and wage wars to advance their interests. We see how global powers, under the guise of good intentions, shape public opinion, support their preferred forces, and push for protests or suppression. And no side is "absolutely righteous." -

Do you think AI is going to be our downfall?What’s gonna happen when you replace most jobs with AI, how will people live? What if someone is injured in an event involving AI? So far AI just seems to benefit the wealthiest among us and not the Everyman yet on Twitter I see people thinking it’s gonna lead us to some utopia unaware of what it’s doing now. I mean students are just having ChatGPT write their term papers now. It’s going to weaken human ability and that in turn is going to impact how we deal with future issues.

It sorta reminds me of Wall-E — Darkneos

There was also a wonderful Soviet film, "Moscow-Cassiopeia." According to the plot, a distress signal came from Cassiopeia. A spaceship carrying children was sent to rescue them, as they would have been grown by the time the ship arrived. Upon arrival, it turned out that the locals on Cassiopeia had entrusted all their chores to robots, focusing instead on creative pursuits. However, the robots rebelled and drove all humans off the planet. I doubt this film has been translated into your language, but if so, I recommend watching it.

I use AI daily. I notice the same in others. What strikes me is how much the level of business correspondence within the company has improved, the quality of presentations has increased, and the level of critical thinking has risen. I believe my environment is under the control of AI =)

Well, some human skills have truly been deflated. At the same time, AI provides an easy and quick answer to any request, while yesterday's incompetent performs miracles. Young people understand that they don't have to bother with cramming at all—it's much easier to delegate tasks to AI.

It doesn't seem so bad. But people are losing knowledge. They're losing their thought systems, their ability to independently generate answers. Today's world is like a TikTok feed: a series of events you forget within five seconds.

What will this lead to? I don't know exactly, but the world will definitely change. Perhaps humanity's value system will be reconsidered.

There's already a "desire for authenticity" emerging—that is, a desire to watch videos not generated by AI, to read text not generated by AI.

I already perceive perfectly polished answers as artificial. "Super-correct" behavior, ideal work, the best solution are perceived as artificial. I crave a real encounter, a real failure, a real desire to prove something. What was criticized by lovers of objectivity only yesterday can somehow resonate today.

About 25 years ago, when a computer started confidently beating a grandmaster at chess, everyone started shouting that it was the end of chess. But no. The game continues, and people enjoy it. The level of players has risen exponentially. Never before have there been so many grandmasters. And everyone is finding their place in the sun.

Everything is fine. Life goes on! -

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

I agree that the parallels you mentioned between the contemporary United States and Germany in the 1930s seem apt at first glance, especially in the context of emotional tensions and attempts to restore national identity. However, as you rightly noted, Hegel's dialectic presupposes a clear antithesis—in Germany's case, it was a national resentment directed at external perpetrators (the Treaty of Versailles).

In the United States, however, in my view, the antithesis is more internal. The contradictions we observe are more closely linked to divisions within society—between various ideological, cultural, and economic groups. This is not so much a struggle against an external enemy as an internal identity crisis, which is generating the fragmentation of a thesis that was once united in the form of the "American Dream."

One could say that the United States is currently in a phase of "high tension," but this tension is not directed outward, as it was in pre-war Germany. Instead, it is tearing apart the social fabric from within. Here it's appropriate to recall Machiavelli, whom you didn't mention, but whose idea of creating an "enemy image" to consolidate society seems relevant. The problem, however, is that in the contemporary US, such an enemy image (whether external or internal) is too vague to unite society. Attempts to artificially create one—through the rhetoric of militarism or culture wars—so far appear unconvincing, perhaps due to the loss of "soft power."

And here we come to the key point: the loss of ideological certainty. Western metadiscourse, which until recently was perceived as universal, is beginning to lose its persuasiveness not only to the outside world but also to the West itself.

When internal contradictions become too obvious, exporting an ideology—democracy, liberalism, or other values—becomes difficult. This, in my opinion, is the "end of Western metadiscourse" referred to in the title of this thread. We are witnessing not just a change of phase in Hegelian dialectic, but perhaps the emergence of a new synthesis that has not yet acquired clear outlines. -

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

I haven't encountered a classification of types of individualism. Please share links for further study. This would be very useful for me.

Your idea of "defensive" individualism as a response to loneliness sounds compelling and adds nuance. However, I don't think it contradicts my paradigm, but rather complements it. In my analysis, I focused on individualism as an ideology and cultural foundation (from Christian salvation to liberalism), rather than as a personal reaction.

At the same time, let's try to connect these levels. For example, the "defensive" type is possible precisely in societies where individualism is already ingrained: in a primitive community or collectivist culture, self-isolation would lead to exile or death, but in a liberal world (where "I don't care what John does"), it becomes a rational survival strategy. Thus, even defensive individualism rests on the same foundation—freedom from collective obligations.

Are there examples of defensive individualism within traditional or collectivist societies? Yes, I think there are, and it's not uncommon. For example, hermitism—both individual and group. Other examples (but they're more about moral individualism) include Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn in the USSR. The former was a prominent enough scientist to be subjected to harsh repression, while the latter was exiled from the USSR.

My theory (individualism as a product of Christianity and liberalism) isn't refuted by these examples, but it is qualified: individualism in collectivist societies is rare and requires specific conditions. This makes it the exception rather than the rule, which confirms the idea of a "foundation" in liberal societies where individualism is systemically supported.

In general, developed countries' propaganda toward their geopolitical rivals is based, among other things, on the idea of conveying to citizens beliefs about personal uniqueness, inimitability, and individuality. For example, Voice of America and Radio Liberty, US-funded broadcasters, broadcast programs emphasizing individual rights, freedom of speech, and personal success. For example, they told stories of "independent" Americans who achieved success without state control, contrasting this with the Soviet system, where "everyone is responsible for everyone else." This sowed the seeds of rebellion: "Why should I depend on the collective when I can be independent?" Such broadcasts reached millions of listeners in the USSR, contributing to the rise of dissidents like Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn.

Today, a similar tactic is being used against China and Russia, where the emphasis on individualism is being used to criticize authoritarian systems. Propaganda focuses on "personal uniqueness" as a universal value to provoke internal conflict: "Why should I be responsible for the affairs of the state or the collective?"

But this process is two-way: rivals also use propaganda: China and Russia promote collectivism as a "defense against Western individualistic decadence." The narrative of "personal unhappiness" is also characteristic of their approaches. Collectivist propaganda directly attacks individualism as selfishness.

The situation seems acute, and instead of embracing the best in each other, everything is gradually returning to a "clash of systems," albeit in a different form. I don't like this. The idea of this topic was, among other things, an attempt to find ideological compromises. However, I must admit, my naive attempts always fall on the rocks of economic interests. -

The value of the given / the already-givenThe way the question is formulated, it looks like moralizing. "Do people need" ... Who are we to tell others how to live their lives ... — baker

Perhaps, indeed, my formulation sounded like an attempt to answer for others, but my intention was different—not moralizing, but exploratory. The question "Should people..." is not a directive, but an attempt to understand: does a person have an existential need to evaluate their own life, or is it perfectly acceptable to live without engaging in this reflective labor?

If Socrates had been accused of moralizing for such questions, he would likely have merely smiled. After all, his famous line, "The unreflected life is not worth living," is precisely the assertion that it is human nature, and perhaps even necessary, to stop from time to time and reflect on how we live.

In the 20th century, existentialists also did not propose universal "oughts," but viewed freedom of choice and the recognition of the absurd as important components of the human experience. In "The Myth of Sisyphus," Camus wrote something like this: "To live is to question."

So my question is non-directive. Not "should" or "shouldn't," but rather: what changes in our lives when we evaluate them? And is it possible to learn to appreciate them without loss and catastrophe? -

The value of the given / the already-givenWhether you were in fact on the "brink of loss" is a matter of interpretation.

It's also possible to conceive of the situation in another way, for example: You had been on the brink of loss all along. Prior to having feelings for that other woman, you weren't fully committed to your wife and family to begin with, and this lack of committment (perhaps unknown even) is what made the emotional straying possible at all. — baker

You can interpret it this way, or you can interpret it another way: you could say that "my head doesn't turn left without a reason." However, that's exactly how I felt and that's exactly how I interpreted the experience. It's neither good nor bad, nor right nor wrong. But this was a review of my experience. I don't recommend turning this approach into a practice.

We buy things we don't need with money we don't have to impress people we don't like.” — baker

An interesting expression. I don't envy people who live by such principles. How do you see a solution to this problem? -

The value of the given / the already-givenVery good, thanks for the feedback. Honestly, I wanted to hear opinions like these because they broaden the discussion. Thank you for your input.

So:

For one, I am skeptical about such practices. Does Donald Trump write a gratitude journal? Successful, important people don't seem like the types who would do such things, because it seems to me that it is precisely because they take for granted what they have (wealth, health, power, etc.) and because they feel entitled to it and demand it from life that they have it in the first place. They don't beg life; they take from it. — baker

Who is Donald Trump—and why should the way he conducts his affairs matter to me? Why should his lifestyle or mindset be my guide? And, most importantly, why should "success" even determine my value system or level of happiness? Just because it's accepted—because that's the dominant discourse?

Let's say someone chooses the path of wealth, influence, and external recognition—a path that essentially echoes the Calvinist paradigm: if you're successful, you're chosen by God, therefore you're worthy. But does this make a person truly happy? And will you really, by giving up many human qualities for the sake of "success," necessarily achieve it?

Here's an empirical example: South Korea. A society where success is cultivated from childhood. A child studies from dawn to dusk, deprived of spontaneous joy, then studies to the bone at university, then works beyond their limits to pay the rent and bills. And here it is, the long-awaited result: you have the ghost of a chance to have one child (you can't afford more). Society is objectively "successful," but look at the birth rate, the burnout rate, and the suicide rate.

I'm not saying this path is inherently wrong—but the task of philosophy, it seems to me, is not to give instructions on "how to live," but to offer a different perspective. To question the obvious. And to help people see value where it's usually not sought—not only in victories, but in the very fact of being.

Secondly, all such practices that I can think of are somehow religious in nature. As such, it won't be possible to carry out those practices meaningfully unless one is actually a member of the religion from which they originate, because those practices are only intelligible in the metaphysical context provided by said religion. — baker

It's always connected to religion, metaphysical, and therefore imprecise. It sounds very much in the spirit of a positivist approach. And yes, I have nothing to argue or prove here. However, I did ask this question above:

Christian "Thanksgiving" cannot be taken out of context and viewed as a standalone tool. It may have some effect, but the content itself will certainly be missing. Taking "Thanksgiving" out of Christianity and calling it the key is very reminiscent of a "success coach" and his attempts to offer five simple steps to achieving harmony and prosperity.

Do you think any attempt at simplification is impossible and will be empty, or is some systematization possible to convey the idea without delving into it? — Astorre

Let's say a person is not religious, rational, focuses on verifiable judgments, and demands precise answers to precise questions. What can be offered to such a person? Is it necessary for them to first accept a religious or metaphysical worldview in order to begin to appreciate what they already have? Or can philosophy offer approaches that allow this to be done outside of a religious context?

Do you need to "value" anything at all if you're not religious? Or is it enough to simply live without asking such questions? These are the main questions of this topic for me. If you can answer these questions, I would be grateful. -

What is a system?

I used to be more of a positivist than I am now and believed that a universal tool could be provided. Systematic studies in philosophy, particularly ontology, forced me to reconsider my views in the spirit of postpositivism. The same fate befell Heidegger (as far as I know). He began by wanting to provide a universal tool, but ended by admitting that his works were metaphysics.

One could say that Heidegger moved from methodological optimism to profound doubt in the very project of universality and rational explanation. This, in a sense, echoes the transition from positivism to postpositivism in science and philosophy: the rejection of the idea of ultimate truth, the recognition of the contextuality of knowledge, the role of language, tradition, and historicity.

But if you manage to discover the foundation of all this, please share it. -

What is a system?

Somewhere at the beginning of this thread, I wrote the following:

This leads to the conclusion that a system, in our everyday understanding, is a conscious construct. — Astorre

You're asking for a lively discussion, not just references. And here's my first assertion:

The word "system" was invented by humans to describe phenomena.

This word successfully describes some phenomena and less so others: for example, "system" is suitable for describing the mechanism of a watch, but it's inappropriate for describing a phenomenon such as the system of the world order. In short, in my opinion, nothing is a system in itself, but we are comfortable calling a system some part of what we work on/study/research/create. A system is a concept we use to reflect the structures of the world. And since the word "system" is a concept, we (humanity as a whole) can agree on what we understand by this word, and that will be an accurate definition of the concept.

However, yesterday, walking down the street, I thought: Is there anything in the world around us that couldn't be called a system? A stone is a system of molecules, an anthill is a survival system, and the solar system is a system of orbits. Therefore, a system is everything: from any existing entity to the value system in our heads.

From the above theses, it follows that there cannot be any "matter" or "substance" of a system. A system is not a thing, but a way of talking about things.

So, can we name, define, and set boundaries for this concept? I think it's possible, but we should define it not by searching for the matter of a system, but by identifying the characteristics inherent in systems. In other words, the main idea is to define the characteristics of a system.

So, here are what I would call the characteristics of a system:

1. It consists of elements

2. The elements interact with each other

3. By "working" together, the elements develop new properties than each element individually

4. Boundaries (which the knower will name, since otherwise the system is everything)

5. The elements are structured (organized and ordered)

6. Stability over time (the pattern persists for a sufficiently long time, at least more than a single moment). -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?

I look at this problem from a slightly different angle:

Chalmers calls the problem:

There are so-called soft problems of consciousness—they are also complex, but technically solvable. Examples:

How does the brain process visual information?

How does a person concentrate attention?

How does the brain make decisions?

These questions, in principle, can be studied using neuroscience, AI, and psychology.

But the hard problem of consciousness is:

Why do these processes have an internal sensation at all?

Why doesn't the brain simply function like a computer, but is accompanied by conscious experience?

We know what it's like to see red, but we can't explain why the brain accompanies this perception with subjective experience.

So (as Chalmers writes): Either something is missing in modern science. Or we're asking the wrong question.

Chalmers asks a question in the spirit of postpositivism: Any scientific theory is not necessarily true, but it satisfies our need to describe phenomena. He suggests rethinking the question itself. However, he hopes to ultimately find the truth (in a very positivist way). He still thinks in terms of "problem → theory → solution." That is, he believes in the attainability of truth, even if only very distantly.

As for me, I would say this: if the truth of this question is unraveled, human existence will lose all meaning (perhaps being replaced by something or someone new). Why? Because answering this question will essentially create an algorithm for our existence that can be reproduced, and we ourselves will become mere machines in meaning. An algorithm for our inner world will emerge, and therefore a way to copy/recreate/model the subjective self will emerge.

From this, I see two possible outcomes: Either this question will be answered (which I would not want in my lifetime) or this question will remain unanswered (which promises humanity to continue asking this question forever in any way and for any reason, but never attaining the truth). So my deep conviction on this matter is this: mystery itself is what maintains the sacredness of existence.

At the same time, as a lover of ontology, I myself ask myself these and similar questions. However, the works I have written on this subject do not claim to be truthful, but rather call for an acceptance of incompleteness. Incompleteness and unansweredness lie at the foundation of our existence, and we must treat this with respect, otherwise our "miraculous" mind, with its desire to know everything, will lead to our own loss. -

Laidback but not stupid philosophy threads

I was hooked on this forum from the first day I discovered it. I later joined myself. What's really good is that any topic, even the most naive, won't go unnoticed. And they definitely won't tell you what an idiot you are, although they'll hint at it =). I've tried discussing a variety of topics here, from strictly theoretical ones to politics or gratitude practices, and I've always found a response. Well, I like it (although being too harsh is also not welcome—especially criticism of liberalism). So, I think any topic you discuss will find its audience. -

A Living Philosophy

Your passion for empathy and dreams of a better world is the spark that ignites hearts. Yes, Tom and the guys find fault, but it's like a whetstone for your ideas - makes them sharper! Try to add specifics: instead of "Mother Earth," tell us how, for example, joint projects of local communities can really change something. Small steps, like those good deeds that you wrote about - this is the way to big. Keep shining, we are all here for a better future, just each in its own way! -

The value of the given / the already-given

In our area, builders like to repeat: "It was smooth on paper, but they forgot about the ravines." This phrase perfectly expresses the essence of any idealistic approach to understanding human activity. Attempts to accurately structure, describe, or predict people's behavior tend to face a reality that is invariably richer, more complex, and more controversial than any scheme.

Reality has many levels, contexts and accidents that defy complete theoretical coverage. In this sense, any model that claims to be universal inevitably tests the limits of its applicability, especially in the field of humanitarian knowledge. This is often seen as a critique of the excess belief in causal rigor and scientific accuracy characteristic of positivist thinking.

Nevertheless, a person has always been characterized by the desire to transform observations into knowledge, and knowledge into a system capable of prediction. So what we call science was born. And although humanitarian disciplines are often criticized for the lack of strict formalization, they certainly have a certain predictive power. Let not in the form of rigid algorithms, but in the form of landmarks that allow you to think within the framework of probabilities, trends and meanings.

The search for consistency, even if it is conditional and incomplete, remains intellectually fruitful. It allows not so much to predict the future with accuracy as to set the direction of thought and action in a complex and multidimensional reality.

I would like to repeat my question:

And the most important question that arises in this regard: Do people need to make this most accurate assessment of what they already have in their daily lives, or is it easier to simply live life as it comes? — Astorre -

The value of the given / the already-given

Thus, this method is connected with assessing oneself not as the center of existence, but rather with experiencing gratitude simply for the fact that we exist and that something in the world operates not by our will, but according to its own laws—and yet harmoniously; seeing meaning and beauty in simplicity, in the natural flow of time, in limitations, and not only in exceptional experiences.

If I may express it briefly: The Method of Humbly Presence is a conscious way to appreciate life without loss, accepting oneself not as the center of the world, but as its natural part. Through the rejection of egocentrism, gratitude, sobriety of perception, and the ability to rejoice in the simple are born.

This review can be summarized as follows:

The method of active gratitude is a path to gratitude through action: dance, creativity, good deeds. Not reflection, but living experience—especially compassion—leads to humility and an awareness of how much has been given. -

The value of the given / the already-givenThere’s repentance. I don’t mean this in a religious sense, but as re-construal. The best way to appreciate anything in our life is to refresh its meaning for us. Simple attention won’t do this. Stare at anything long enough and it disappears. We must always re-construe in order to retain relevance. — Joshs

I had one positive experience in my personal life that allowed me to truly appreciate this approach. While married, I fell in love with another woman. I was faced with the choice of leaving my family and choosing this woman, or weaning myself off of my feelings for her (it's a shame dialectic isn't possible here). Essentially, at that time, I completely analyzed and rethought all my values—family, children, etc. As a result, I strengthened my initial position, realized how truly valuable they were, and chose family. Fortunately, women gave me the opportunity to make an informed choice, and my wife accepted me (by the way, I didn't have any physical affairs).

I remember that period in my life, which lasted about a year, well. My values were tested in practice. I became convinced of them. But again, all this became possible only on the brink of loss. -

The value of the given / the already-given

Reading your comments, I, as usual, begin to criticize myself for a certain superficiality, since you always very aptly develop your position on the topic of religion, in which you are clearly a great expert.

Since you come from a background, I'm sure your familiar with the motif of portraits of Orthodox monks in their monastery's ossuaries where they are sitting contemplating the skulls of their deceased brothers (or sisters I suppose) by the light of the alter. Some Catholic saints are also often depicted with a skull for similar reasons. I have heard of Eastern monks even sleeping in their own eventual caskets as a meditation on death. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Frankly, before I joined this forum, before I delved into the topic of dualism (body and soul) in Christianity and wrote a short essay on it (you may remember), I was somewhat skeptical of this skull worship. This practice seemed strange to me, since I assumed the soul had already left the body long ago, somewhere else—what was the point of cultivating these bones? However, after realizing that Christianity was previously more about monism and the resurrection of the whole person, these practices began to make sense to me. And as we've discovered, Orthodoxy has preserved this monism and veneration of the body (although few priests today understand this).

Thanksgiving: the one you're mentioning, which is now contextualized. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree. Christian "Thanksgiving" cannot be taken out of context and viewed as a standalone tool. It may have some effect, but the content itself will certainly be missing. Taking "Thanksgiving" out of Christianity and calling it the key is very reminiscent of a "success coach" and his attempts to offer five simple steps to achieving harmony and prosperity.

Do you think any attempt at simplification is impossible and will be empty, or is some systematization possible to convey the idea without delving into it? -

The value of the given / the already-given

The idea wasn't to avoid answering the question, but rather to expand the discussion. The topic arose from my observation that people often both undervalue and overvalue what they already have. In the first case, regret follows the loss, while in the second case, relief (but again, regret over lost time) sets in. I played the role of a "German idealist" of yesteryear, asking whether it was possible to accurately assess what was already "given" to avoid these pitfalls. I cited approaches I knew. In a sense, these approaches help value what is given, but they lack the precision that would likely be of interest to utilitarians. Another question: is it even possible to accurately assess what is given?

For example, in business, there are several assessment techniques: financial valuation of assets (e.g., market value, liquidation value); human resource valuation (assessment of competencies and potential, and replacement cost); Intangible asset valuation (financial performance, brand strength); intellectual property valuation; SWOT analysis of resources (identifying strengths and weaknesses, understanding their applicability in the current environment); VRIO analysis (Value, Rarity, and Imitability (difficult to copy)); efficiency analysis. All these techniques, while somewhat costly, pay off handsomely in the long run.

And the most important question that arises in this regard: Do people need to make this most accurate assessment of what they already have in their daily lives, or is it easier to simply live life as it comes? -

The value of the given / the already-given

By the way, it is strange that there is no "axiology" section on the forum, because this section of philosophy is probably looking for answers to such questions. I know some practices that can be grouped into three approaches.

1. Practice of attention — training to see, что уже есть (Buddhism, phenomenology, awareness, Gurdjieff).

2. Practice gratitude — active recognition of values (Christianity, psychology, partly stoicism).

3. The practice of thinking about death and the transition — to strengthen the presence without plunging into fear (Sufism, Stoicism, partly Heidegger).

I think this field of knowledge goes beyond theoretical philosophy and is a more practical field. Maybe someone knows other approaches? -

Is there a purpose to philosophy?I don't think everyone is a philosopher like he says, most people don't really seem to question the way things are in life and just go along with it with what they were taught. From my understanding our brains are sorta resistant to what philosophy requires of us. — Darkneos

Today, I see it this way: the purpose of philosophy is to provide some relief to those who wonder about the state of affairs in life. -

Information exist as substance-entity?Information is a form that can mean, that reveals itself in a meeting with someone who can read it. Thus, information is both a form and an event.

-

The End of the Western Metadiscourse?

As I noted above, the question "what should we free ourselves from now?" was a kind of logical reductio ad absurdum.

In fact, recently discussing the topic of outdoor practices, I thought about the fact that a contemporary has to intentionally leave his comfort zone in order to feel alive again.

It turns out that our desire for safety and comfort has led us to a place from which it is worth running. And I fully support your idea, only in a slightly broader sense: in order to feel alive, some need is needed, some dissatisfaction, some aspiration. Otherwise, what is the point of striving for inaction, as in Buddhism, if we do nothing anyway?

So I began to plan a trip to nature, and options immediately appeared in my head to go to the mountains or to equipped gazebos on the river bank. But why not go to the steppe under the scorching sun with sand in your face and snakes? It turns out that the mind itself chooses the safest and most comfortable option.

But where is the authenticity then?

The thing is that perhaps philosophers will not have to invent anything themselves, since the current overconsumption and population growth will reformat everything in the most optimal way, so that we will not even notice it.

Astorre

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum