-

Liberté, égalité, fraternité, et la solidarité.Liberal democracies went through centuries of struggle before such principles as the right of free speech, freedom of assembly and conscience, the practice of government with a 'principled opposition' became established. Along with these was the principle of pluralism, which is that it is possible for people with very different points of view to actually co-exist.

But I don't know if there is any inherent recognition of these principles in Islamic political systems. — Wayfarer

If I get Marx right, one of the reasons the present countries of North Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere didn't develop liberal democracies is that they did not go through a long period of industrial development which could have helped them build more inclusive communities, a more secular society, more tolerance, and so forth.

The fissure of Islam is sort of (crudely) like the major fissure of Christianity into Roman and Greek wings. The conflict between these two wings was unproductive. It wasn't until the Latin church was split by Martin Luther, John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, Jan Hus, Peter Waldo, and John Wycliffe that the benefits of reformation began to accrue to the western churches. Islam hasn't had its reformation, yet.

Islam has existed, for the most part, in relatively poor countries where there has been strong tribalism. In the last century oil, of course, lifted the prosperity of various nations, while maybe not doing all that much for the individual citizen.

So we have... a couple billion people who follow a moderately to extremely conservative faith, do not have democratic traditions, do not have a lot of prosperity, do not have a strong secular education system, and so forth. Thanks to technology, they are now drenched in access to all sorts of culturally abrasive content, some of which they probably like, and some of which they don't.

Fundamentalist Islam is as bound to be as resentful as fundamentalist Christianity. By its nature, extreme conservatism is a resentment against all that is modern. The conservative Christian preachers who backed the clock up to some vague pre-20th century point in time and are always calling down damnation on so-and-so or affirming that an earthquake is the result of rampant sodomy and pornography, or what have you, is of a piece with the ranting mullahs. A conservative Christian enclave would be about as pleasant as the ISIS caliphate.

it might be a good idea if liberal, secular, and democratic areas such as North America and Europe became more articulately supportive of cultural virtues and more explicitly proactive about cultural evils. The world needs tolerance of fundamentalism (Christian, Islamic, or Hindu) like it needs a return of the black plague.

Outrages like the mob murder of a Moslem in India for allegedly eating meat from a sacred cow shouldn't be swept under the cultural relativity rug. India should investigate and punish the mob. There are religious outrages in America instigated by fundamentalists that shouldn't be tolerated either -- like teaching creationism in schools (secular or religious schools). Maybe liberals should get off their duff and wreck the place. Anyone advocating, teaching or recruiting suicide bombers and terrorists should, perhaps, be executed forthwith. Prospective suicide bombers and terrorists can go to the same wall. If madrasas in Europe or the US (or anywhere else, as far as I am concerned) are teaching anti-democratic, anti-liberal, anti-secular doctrine, then be gone. If moslem prisoners are being radicalized in prisons, then isolate the teachers and subject the students to political reeducation.

I can't think of any effective way to change Saudi antediluvian theology. If there is so much oil around, maybe we should organize a boycott of Saudi grease. Maybe the remotely controlled self-destruct mechanisms in the AWACS we sold them should be activated.

Too harsh? Too violent? Not enough cultural sensitivity and respect? What's your suggestion? -

Liberté, égalité, fraternité, et la solidarité.Last night on the BBC a Northeastern University [Boston] professor who studies terrorism made a useful observation:

-

"What did the terrorists want to achieve? Well, most people observe what happened after the terrorist attack and cite those consequences as the intended result. So, the purpose of 9/11 was to involve the US in a mid-eastern war -- and they were successful. Or, 'the purpose of the attack was to make life more difficult for ordinary people.' And sure enough, life was more difficult for ordinary people.

In fact, we generally have no idea what the intended result was. Perhaps the terrorists had rather grandiose intentions which totally failed. Or perhaps they had not thought through the long range consequences of their terrorist attack -- perhaps they had rather minimal objectives." -

Liberté, égalité, fraternité, et la solidarité.I just wonder if the knowledge that the audience could be armed, might likely be armed, would have changed the appearance of these events being 'soft targets'. — ArguingWAristotleTiff

I think we all need to recognize a distinction: What makes sense on a ranch in the arid wastes of Arizona (Anasazi word for "arid waste") or on a farm in the frozen wastes of Minnesota (Ojibwa word meaning "frozen waste") or in the hilly wastes of eastern Kentucky (Chickasaws word for "hilly waste") isn't a good idea in dense urban environments. If the Beast is slouching down the road leading to your adobe abode, shoot the son of a bitch -- then call 911. Same advice for anybody else living a long ways from the nearest patrol car.

The reason it doesn't work in dense urban settings is that there is too much friction all the time, and too many potential targets. Too many people end up getting shot by mistake (or even if the target is correct, bullets miss and often keep going long enough to run into somebody totally uninvolved). The thought of a gun fight breaking out at something as small as a rural slow pitch softball tournament is chilling.

Another reason it isn't a good idea to arm everybody to defend against terrorist attacks is that these attacks tend to be a total surprise, and there are enough variables to keep even the most agile of Navy Seals off balance, let alone your average good shot at squirrel hunting.

Like: Timothy McVey and his truck load of fertilizer and jet fuel with which he blew up the Oklahoma Federal Courthouse. Or 9/11. Or the Anthrax attack, the sarin attack (in the Tokyo subway), or the unibomber, or the crazed suicide mass murderer walking into a crowded Bagdad market and exploding themselves and everybody else nearby. Speaking of having doubt in one's government... David Koresh and his Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas were well armed and knew the feds were coming for them, but still ended up burning to death at the hands of the United States DOJ's Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. (Talk about an agency with a mixed agenda!) That's what led to the Oklahoma bombing. (Oklahoma is an Arapaho word for "gawd awful waste".) -

Points of order in New ZealandSomething is definitely cuckoo in Kangerooland but I can't quite figure out where cuckoo and proper begins and end.

a. Australia has the usual and customary collection of dehumanizing practices to use on detainees.

b. Australia has always been kind of fussy about who moves there, and who stays there too, apparently.

c. The detainees may or may not have committed rape.

d. I can't see the connection between the guilt or innocence of the detainees and the insult the sexually assaulted MPs experienced.

e. I don't see how the self-proclaimed sexually assaulted MPs were heinously abused by the speaker or the PM. On the other hand, I don't quite get why it was found necessary to evict the MPs, either.

Sounds like a SNAFU. -

Poll on the forthcoming software update: likes and reputationsOne should say what one thinks as effectively as one can and then let the chips lay wherever they land. If people don't like it, tough bounce. I voted to get rid of the likes entirely.

-

The USA: A 'Let's Pretend' Democracy?Three good examples, small to large:

A bond issue for a new school failed four times in my small "home town" (where I have not lived in 50 years). Are the locals troglodytes who were against education? Not at all. The residents correctly perceived that a new school was needed, BUT the plan offered by the school district was loaded with a property enhancement scheme for a single property owner. The People weren't against the school, but they were against the deal whereby the property owner (a resident of the town) would benefit excessively (and in terms of property values, exclusively). A new school was needed, but the same plan kept being presented for a vote. Eventually fatigue and need won out. The property (outside the city boundary) was built and the development of land went forward.

The major league sports teams in Minneapolis (NBA, NFL, MLB) have all wanted the city to built them new stadiums. The Twins were first in 1979. It went up with little objection, much at public expense. But it was relatively cheap. Then the NBA wanted a new court. They succeeded in getting a multi-use facility which, I think, the city owns. Then the Twins grew tired of their 30 year old facility which they had been sharing with the Vikings and whined, cajoled, threatened, pleaded, contemplated suicide over, until another bond issue was proposed. The citizens of Minneapolis rejected the bond issue but it was re-presented, "once more with feeling" (lots of pressure) and it passed. The Twins own the stadium.

In the next election a referendum was passed by a landslide prohibiting more than $10 million being spent on new stadiums WITHOUT public approval. Next the Vikings wanted a new stadium. The creep who owns the team is a billionaire property developer. A proposal to spend something like half a billion of public funds on a new stadium was roundly defeated. End of story? Not at all. Property interests went to the legislature and managed to get the Minneapolis law overridden. Next chapter: the state approved the stadium for the Vikings ($1 billion plus) much of it at city expense -- i.e., paid for by taxpayers who emphatically declared they didn't want to have it or pay for it. So, we got it shoved up our asses even though we had clearly rejected it. The Vikings own the stadium.

Who is next? Soccer. Fortunately for Minneapolis the stadium is located in St. Paul and is not expected to cost more than mere tens of millions. The facility is part of a large property redevelopment which the city government wants. (The property used to be a mass transit bus garage next to the freeway.)

Then who? Hockey. Then who? The Werewolves will be back for a new publicly funded court. Then who? Badminton? LaCrosse? Croquet? Bowling? There must be some rich family who owns a sports team that hasn't sucked off our public teat yet.

The public considers Social Security about as sacrosanct as the Holy of Holies and God Himself. None the less, Congress has been systematically avoiding changes in funding which would be entirely feasible. Instead the COTUS has piddled around and entertained various proposals which would essentially set up a shit house in this holiest of holies. Turning it over to the stock market, or letting it shrivel up, or making the poor pay for it are the best ideas they can come up with. Limiting benefits for those already very wealthy and secure, and increasing the SS tax on those who are flush in the lap of luxury have been non-starters. Swiping social security funds to pay for other stuff, of course, has been going on for a long time. Disability programs aren't very popular in COTUS or the rich.

The very rich and privileged look at social security and disability (never mind welfare) programs like a New York Times cartoon showing Ben Carson looking at a Roman aqueduct and denouncing it as "The socialist Romans used these to hand out water to their lazy, freeloading citizens."

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2012/07/08/opinion/sunday/the-strip.html?ref=sunday#1

-

The Ultimate Game of Hide and SeekDoes the spirit of a congregation create the spirit of god, or is it "the call of the spirit of god" that arises?

It seems to me that god, goodness, fellowship, fulfillment, meaning, validation, comfort, and all that good stuff is created and/or found in life lived together. We have to go out and seek others; work, play, sing, laugh, eat, play together. We have to open up to each other (incrementally). We need to accept each other. Church isn't the only place this happens, and honest church people know that sometimes this does not happen in church at all--anywhere but. Bars, workplaces, ball parks, trains, back yards, kitchens, beaches, barracks and battlefields, hospitals, prisons -- really, there is no place "life together" can not happen.

That said, often enough we are isolated, alone, lonely, longing, sad, self-contained, closed off. That's a big piece of our problem as humans. -

Welders or Philosophers?Do you prefer to do eclectic ark welding or do you weld with an oxymoron torch?

-

Welders or Philosophers?...snorted coke out of a Cuban hookers ass... — discoii

Goodness. That doesn't sound like a healthy practice at all! Plus, it exemplifies the objectification and the oppression of third world women by rich North American white men. Tsk, tsk. tsk. -

Welders or Philosophers?I'm not seeing nearly enough welds in this thread. It is clearly dominated by philosophers. Think how much better it would be, stronger and more solid, if the posts were properly welded instead of being cobbled together with flimsy ideas. — unenlightened

Isn't it the case that there are no two ideas so stupid but some philosopher has tried to weld them together? -

Welders or Philosophers?Marco is clearly the best looking male candidate among the Republicans, beating out Carly and Donald both. He will wield his well-welded genetically happy features to good advantage as philosophical advisors no doubt suggest.

We do not need more spot welders. Robots are perfectly capable of spot welding. More technically sophisticated kinds of welders are in demand. They don't need a degree in engineering, but they do need specialized training. Ditto for computer-controled lathe operators and the like. The US makes a lot of high-end products and assembling line methods are not very important in high value manufacturing.

I needed half of $77,000 to be happy, though at my highest paid and unhappiest job, $77,000 wouldn't have helped much. $777,000, or $7,777,000 wouldn't have done the trick. Bad time can't be bought off. -

Bad ArtOne of the interesting things about the soup cans, the Brillo pad box (Warhol) or the the pop art figure (Roy Lichtenstein) is that they these designs had already been used millions - billions? - of times before Warhol and Lichtenstein made them. Campbell Soup cans were designed in an advertising/PR/Branding company studio. The soup can didn't fall from the sky. Ditto for Brillo pads and their boxes, and ditto for the cheap printing techniques used in comic books that became a piece of Lichtenstein's Pop Art. All this stuff was pop art (literally) before it was Pop Art. Campbell Soup could have printed "tomato soup" in a totally undistinguishable font, black ink on crappy paper. Strictly generic. Ugly.

It is the case that if an artist can declare his work to be art, there must also be an audience to confirm, validate, and appreciate the work. No audience, no art. The Lascaux Cave paintings were not art for 25,000 years, then suddenly, ART! They are art now because they were hailed as great art from the ancient past and audiences (of reproductions) validate that judgement. (The individual Cave Artist's peak turned out to be a human plateau. The stuff on the cave wall is pretty damn good.)

Back to soup cans and Brillo pads: If you can not tell the difference between a Warhol Brillo box and a box of Brillo from the store, why should it be called art at all? Perhaps it is a homage to the Unknown Commercial Artist or maybe it is the apotheosis of commercial art? Why not just put the can of soup, the box of Brillo, and the comic book image in a museum? We could do that now, and theoretically we could have done that before either Warhol or Lichtenstein were born, but we didn't. Presumably artists changed the way we look at these objects, the "actual" products and the "actual" art.

Fairly often I find packaging lovely to look at and touch. Sometimes the packaging is better than the product. It's 'artful'.

-

Is an armed society a polite society?In the field of Supply Chain Management there are (I have heard) formulae worked out for how much warehouse space and staff one would need to support x square feet of retail space (like, for a batch of Walmart stores).

I would suppose that somewhere in the bowels of the Pentagon somebody must have worked out approximately how many soldiers are needed to control a city of 4 million, and how much materiél will be needed, and so on. True? False? Anybody know?

Just guessing, but it seems that to control Baghdad (about 4 million in 1987) 200,000 troops would not be excessive -- that's 1:20, but if one is dealing with a discombobulated population that doesn't like each other about as much as they don't like the occupier, that would be about right. To control and manage Iraq we would have needed roughly 1.5 million troops, or about 1/10 of what we deployed during WWII.

Clearly a draft wasn't going to fly for Iraq. We were using national guard troops as an expedient alternative to drafting. No disparagement intended, but the national guard system is made up of weekend soldiers who have lots of concurrent commitments elsewhere, like entirely civilian careers, families, etc. Some of the men in the national guard were relatively elderly--again, no insult intended, but these were not 20 year olds in for 2 years and then out. The wear and tear on the multiply re-deployed national guard troops was pretty severe. -

Bad ArtI think Bob Dylan's early stuff, especially, is great art -- even if the guy was not a great singer to start with and got worse over time. I'd count Hendrix as an artist, no problem, and a lot of other musicians from the 1960s. Of course, rock and its successors don't have to be "great art" to be quite enjoyable.

It does have to measure up to it's genre, however.

I saw the Peking Opera on tour in Minneapolis, it was the third of 3 shows from China. It may have been great art, don't know, can't know. The genre, the idiom, the techniques, the sounds, the words--everything--was pretty much unintelligible to me. I saw a No play too -- same thing: It may have been sublime art, but it was way too far outside my ken to make sense of it. The other two shows from China featured acrobatics, dance, and instrumental music which were entirely accessible.

Was Tommy James and the Shondells "slop", "not art", "art", "good art", or "great art"? I love some of their stuff (it belongs to my long distant youth) but I'm not sure it rises to the minimum of art, even if it measures up to its genre of bubble-gum rock.

-

Currently ReadingTerry Jones, Barbarians (an alternative history) - so far, B+ / A-

Harlan Ellison, Deathbird Stories - so far, A

Robert Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism - so far A-

Christian Wolmar, The Great Railroad Revolution (finished: B+) about American Railroads, from the beginning to 2000.

Peter Gay, Modernism: The Lure of Heresy - so far, B+ / A-

Victor Navasky, Naming Names - so far, C- for boring; put it down.

Gerard Colby, The DuPont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain - so far B+ (page by page I am enraged) -

Nuclear DeterrentOne major threat from nuclear weapons that isn't talked about much is the "nothing can go wrong" problem. Actually, things did go wrong fairly often. Currently the US and Spain are negotiating the details of cleaning up after the January 17, 1966 (!) B-52 crash of the coast of Palomares.

A B52 SAC bomber carrying 4 hydrogen bombs collided with an air-refueling tanker at 31,000 feet. The tanker exploded and the B52 broke up. 3 of the bombs landed on the ground, one in the ocean. The one in the ocean was eventually recovered, intact. 1 of the three that hit the ground did not explode. The non-nuclear explosives in the other 2 did explode, but didn't set off a thermonuclear blast. (H Bombs can be quite fussy about how they become critical masses and produce a fusion reaction.) The explosion did, however scatter the nuclear fuel which was not thoroughly cleaned up 50 years ago. Hence, the current negotiations.

On a few occasions SAC workers in missile silos accidentally dropped tools. The silos are quite deep and the missiles are quite tall, and the fuel tanks are quite thin. A dropped wrench can poke a hole in a fuel tank. Fuel leaks out, ignites, and the explosion blasts away the heavy protective doors on top, throws the missile and payload up into the air, and scatters bombs or bomb parts, depending.

The factories that made plutonium amaze balls (about the size of a grapefruit) had all sorts of contamination problems, and so did the communities near by--like Denver. On one occasion the plant caught fire and burnt off a good share of the roof, and incinerated the plutonium filters mounted on the roof. Plus there was an explosion. A plutonium cloud blew across Denver (and where it landed it remains, like as not). The plant, Rocky Flats, closed in 1992. It was was very dirty (in terms of radioactivity). Some areas of the plant were just filled with cement, because they were too hot to handle. The radioactive soil was covered up (not very deeply). The dump is now a "nature reserve". Cute.

The fires in the plant were difficult to suppress. Throwing water on a plutonium fire is a very, very bad idea. Water can facilitate even plutonium crumbs in going critical. Very bad outcome. Dry sand works better.

The US and the USSR have not solved the problem of how, exactly, to clean up the hundreds of serious messes that nuclear bombs left behind, never mind civilian reactor waste. As far as I know, nobody else has either. -

Is an armed society a polite society?I agree: We aren't willing to fight the kind of war that might make a difference in the Middle East. Having said what we are not willing to do, let me add that I personally have no idea exactly what kind of war that would be. We fielded a very large army in Vietnam, dropped a hell of a lot of munitions, spent a fortune, lost 50,000 soldiers with many more wounded, and still bombed. Needless to say, the Viet Cong were not fielding especially advanced weaponry.

Handguns, hunting rifles, assault rifles, molotov cocktails, and whatever else might be cooked up, would probably be sufficient for the overthrow of a government, provided that the populace has withdrawn it's consent to be governed (a psychological step, not a legal step, of course.) -

Mr. BeanI like a bit of horseradish in coarse mustard, and straight with a few things like roast beef. The black bread and pickles would help. I've tried to like vodka and have not made much progress. So maybe artesian horseradish vodka chilled to -459º F would work.

I'd prefer a good reuben with real pastrami, sauerkraut, actual rye bread, etc. and a pilsner. -

Mr. BeanHorseradish vodka.

The Crown Fountain in winter is definitely less festive than in summer, but still effective on a cold, windy night, but in a different way. Michigan Avenue definitely becomes relatively deserted on weekday nights -- like, by 7:00. The commuters have gone home; such tourists as there are elsewhere. There is a public skating rink in the vicinity too. That evening there were maybe a a couple dozen people skating, having hot chocolate (with skates), and a few passersby. Nice also. Don't know why Minneapolis doesn't do something like that. (Northern cities put up wood fences, and flood the baseball diamonds in the parks for hockey or just recreational skating.)

Minneapolis could, for instance, flood Peavey Plaza, immediately adjacent to Orchestra Hall, and set up a warming house, skate rental, with a hot chocolate and lefse shop. (Lefse is a thin potato crêpe sort of thing, buttered, sugared, rolled up, and eaten as an overpass memorial to bad Norwegian peasant food. There is no other good reason to eat it.) Instead the city wants to rip out the plaza and replace it with... god knows what. Maybe a giant bas relief of Norwegian peasants making lefse as they go mad in their sod huts on the great plains [see Ole Rølvaag, Giants in the Earth, 1924]. Yes, it's dated. It was built in 1970 so obviously it's too damned old.

Here's an article on the neglect of Modernism, discussing Peavey Plaza. -

Nuclear DeterrentClearly nuclear weapons should be outlawed. They are a menace to all creatures great and small. Maybe nuclear war is survivable. Whether one would want to survive it is another matter.

Consider Pakistan and India, two nuclear armed states. Pakistan has 100 +/- bombs, ready to go, and India has more than that. India has satellite-orbiting capacity (so a guided missile is no problem) and Pakistan is working on extending the range of their missiles. We are obsessed with Iran's development of a nuclear weapons capacity, but are apparently only mildly disturbed with Pakistan's and India's arsenal.

Don't we assume that India has a stable government? Can we say that about Pakistan with much confidence? India and Pakistan could, if worse comes to worse, start a cascade of international nuclear exchanges -- so I've heard.

What leverage exists to force, coax, or entice either India or Pakistan to give up so much as 1 bomb, let alone all of them? The Soviet Union and the United States retreated, but we didn't actually give up our nuclear arsenals either. We dismantled warheads, shut down missile sites, some of which were obsolete anyway. It's not all that easy to rid one's military of all those grapefruit sized balls of plutonium. And both the USA and Russia still have working weapons on line. Then there is China, France, England, North Korea, Israel... There are several more countries that could succeed in building nuclear weapons if they were bent on it.

Who, what, how, when, where would a world-wide suppression of the technology be accomplished? Chemical / biological warfare may have been outlawed but I for one am not at all sure that the issue is settled. Maybe among the major powers it is. The rest? Not so sure. -

Mr. BeanI've been to the bean and seen the bean and was mystically drawn up into the omphalos. I was in Chicago on a late 19th century building pilgrimage last week and wanted to take a friend to see it, but it didn't work out. Too windy, too rainy; too many buildings, too little time. Millennium Park is quite nice too, though I last saw it on a winter's night.

Your comparison to La Familia Sagrada is canny.

The omphalos figured into Hellenic religion; Zeus sent an eagle from the east and an eagle from the west and they met at the center of the world (Delphi). Chronos was given a stone called the omphalos; don't know who gave it to him, what happened to it, or what it was good for. Was it a dildo?

The sex-obsessed will see a phallus (phalos) in the omphalos and there is indeed a phallic reference. There's also a reference to the uterus in the word (somewhere, it's hiding. Don't ask me where.) Obviously a very loaded word--uterus, phallus, navel. Omphaloi were important places to the hoi polloi.

Down the sidewalk is another sculpture. In the winter the water is turned off, of necessity. There are two of these glass brick cubes facing each other, about 20 feet apart (-/+). The cubes are made of small hollow glass bricks; each brick has three LEDs, about 2 inches apart. The cubes can display motion, and sound can be added. It looks better at night than in the day time. -

How accurate is the worldview of the pessimist?Whether one is a pessimist, optimist, or flat affect, what information one has available matters. One might be very optimistic about one's financial situation BUT, optimistic or not, if one doesn't have any money left, one is broke. Conversely, a pessimist might feel like he is broke, but having not checked his accounts recently, doesn't know that he is really quite well off.

Selectively reading only encouraging, or depressing, news reports can reinforce the optimistic/pessimistic view of things -- in both cases unreasonably.

It has been known for a long time that people who depend on local television news for their view of the world tend to be pessimistic and fearful. Why? Because "If it bleeds, it leads" and "Bad news is more interesting than good news".

Bad news, bad news! The stock market is down 10%. The sky is falling? Not necessarily. If one has some cash, this is the ideal time to buy good stocks -- buy cheap, sell dear. But the plunge in prices is more interesting than gradual change, so it gets breathless headline coverage. -

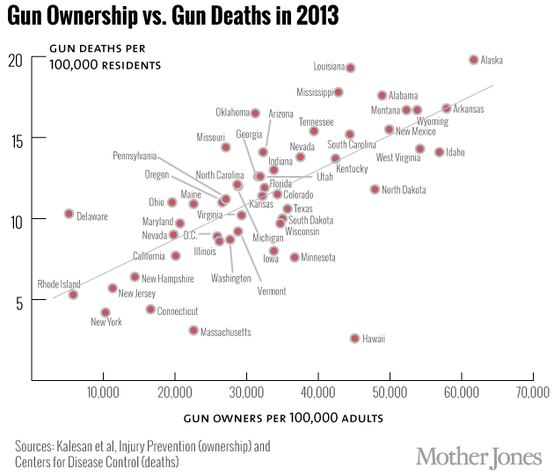

Is an armed society a polite society?Gun ownership and use against persons is the disease. Death is the symptom.

-

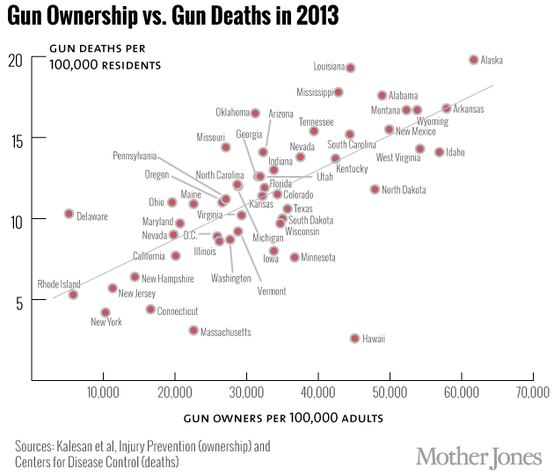

Is an armed society a polite society?Tiff: Arizona is in the high side of gun ownership and gun deaths, but not an outlier. Wouldn't you rather live in a state with outlier stats like Hawaii or Rhode Island (rather than Alaska or Louisiana)?

-

Is an armed society a polite society?A gun, especially a hand gun one can carry on one's person--concealed or displayed openly--is IN ITSELF a powerful influence coloring one's view of the world. So is the rifle in the pickup.

Things are messages. Condoms are about sex, precautions, and protection. Running shoes are about fitness (actual or wishful thinking); a phone is about connectedness; a clock is about management (self or otherwise); a car is about freedom and maturity for a teenager.

The way our local culture interprets objects makes a difference. Clearly Rhode Islanders interpret guns differently than people do in Alaska. Gay guys who insist on barebacking (no condom) are interpreting sex, risk, and life much differently than condom users. People who can turn a cell phone off interpret connection differently than people who drive into concrete walls while texting. -

Is an armed society a polite society?Hey I just realized which thread this conversation is in!!!

Nice welcome for the newcomers — Sir2u

Right. Well, we're here, we have queer ways of welcoming people. Get used to it. -

Is it rational to believe anything?Pyrrhonism — darthbarracuda

Yes, of course anything and everything might be right today and proved wrong tomorrow, but walking around with all that uncertainty is just toooo painful -- worse than arthritis. I prefer tobelieveknow that what is so is so. If I have to switch out a plank in my knowledge system every now and then, that's OK.

I'm perfectly willing to make the occasional adjustment (like, when I started college (back in the paleolithic period) I thought Fred Hoyle's steady state theory was correct, but then I heard about the big bang and decided immediately that made more sense. It has continued to make more and more sense.

I also changed my mind about wearing plaid, paisley, stripes, and floral patterns together. I once thought it was attractive, then I had a flash of insight one day: "God, that looks awful!" -

Is an armed society a polite society?...an armed society, is a polite society and if ever I find myself in need of protection outside of my Rottweiler, that those who are around me will have the ability to act instead of calling for help that too often would arrive to late. — ArguingWAristotleTiff

An armed society is cautious, wary, and nervous. If someone in your armed society wants to hurt you, they will simply be more careful, cautious, and wary about approaching their target. Your big vicious Rottweiler? Distractible and or disposable. Present a bitch in heat (assuming your dog is a male), a hunk of raw meat, pepper spray, or a bullet. Maybe you should get a flock of Rotts.

Have you installed proximity detectors, laser circuits, electric perimeter fences, mine fields, infrared cameras (night vision), atomic death rays, or punji stake booby traps? Perhaps these passive defenses (early detection, electrocution, liquidation) would be more effective. Geese make good guard animals, too. They make a lot of noise when strangers approach, plus you could eat them. You wouldn't eat your Rottweiler would you?

Granted, you live on a ranch and are at least somewhat isolated. Some precautions are appropriate. But don't confuse "polite society" with a "cautious, wary, and careful society" of people who also think a polite society is an armed society, and know guns from the inside out.

How many home invasions have there been in your county during the last 5 years? -

Is an armed society a polite society?Except that gun deaths are nil where nobody owns guns. — Michael

Granted. However, it isn't the gun itself that instigates the shootings. Guns, in themselves, once given unnatural symbolic loadings and fetishist values, are a potential problem that all too often slides into an actual problem.

What IS very problematic is the combination of gun ownership and three values:

1. DIY justice

2. Distrust (or hostility) toward the state and civil authorities

3. "Honor-sensitive" personalities and cultural habits that motivate perhaps deadly retaliation for real or imagined insults.

I am opposed to guns for civilians, other than appropriate rifles for hunting deer, pheasant, duck, geese, turkey, and so on -- as long as the hunters eat what they kill. No trophy hunting. -

Is an armed society a polite society?All they would need is a pressure cooker and BOOM!! They are easier to buy than guns as well. — Sir2u

I was actually surprised (honestly) that something wasn't done about the pressure cooker menace. I can see where one could probably not board a plane with a pressure cooker under one's arm, but they still sell them. At the best stores, too. You would think Bloomingdales would be more socially responsible. Don't they realize that once thrifty housewives are done canning beans and corn in the summer, they start thinking about blowing up the Homecoming Dance? -

Is an armed society a polite society?Skinny Skinny teenagers are, in themselves, something of a problem. So are very, very fat ones. Why can't teenagers be "just right". Don't they know about Goldilocks?

-

Particularism and Practical reasonWe need every trick in the book to get through life without acting in utterly appalling and thoroughly reprehensible ways. We have reason but we are also animals with a combination of base and more refined drives. We live in close proximity and are constantly rubbing up against each other's personal interests, often rubbing them the wrong way.

(IF) We behave well, it is because we have first learned at least some rules and know that breaking the rules will result in our feeling varying degrees of guilt and shame. The antisocial, psychopathic person is not able to feel sufficient guilt (or any at all) and can break rules without personal discomfort.

Guilt is, indeed, a gift. This sharp edged emotion is our best advisor. It may not always be right, but it's message will be clear.

One of the more advanced rules we may (or may not) learn is that persons are central to moral questions: our person and other persons. Whatever the rule, whatever the custom, whatever the peculiarity of the situation, persons are central and more important than material considerations. In the context of Kant's axe murderer, lying is a no-brainer. Of course you must lie. (Isn't the axe murderer a person? Don't Lizzie Borden's wishes count? Yes, they count--against Ms. Borden who wished to sink her axe into her parents' brains.)

What makes the golden rule effective is the identification of the subject person's needs with the needs of the object persons. What satisfies you is my starting point for meeting your person's needs.

We may find ourselves wanting to screw all other interests to serve our own wishes, just as long as we get what we want. Most of us won't go too far, but most of us will, on an occasion, decide to set aside the needs of the one and the many to get something we desire a lot. We may not commit arson, rape, and bloody murder to get the job promotion we want, but we could very well be willing to screw (both meanings of the word) several other people to get the advancement.

Anger, love, guilt, lust, fear, etc.; a focus on persons; will; rationality; habit; learning "commandments" and the meta-rules about how flexibly we can ignore, interpret and obey them--it's all needed to achieve the well-being and good behavior of the one and the many.

Free agents can decide to ignore their moral gyroscope and live with the guilt, of course. An opportunity to embezzle money undetected may be too much temptation, and the person may walk away richer without detection but carry a heavy load of guilt. An opportunity to have the much desired but illicit sex may become available and one will take the pleasure and the guilt together. -

Is it rational to believe anything?How do we separate "beliefs" (confidence in the existence of events or entities for which there is no evidence) from other kinds of estimations of the future (and past) or the unknown? If I say "I believe I will be alive tomorrow" what, exactly, am I saying?

Am I confidently claiming "I will be alive and well 24 hours from now" based on evidence, or is this a belief in unknowable events?

It can't be a statement of fact. There is only a probability that I will be alive in 24 hours. There is also a smaller probability (I hope) that I won't be alive tomorrow. I might and could be dead in 24 hours. (In which case, you should respond and like this post IMMEDIATELY so I have time to enjoy your approval.)

It could be a statement of belief, but it is a conditional belief: I believe I will be alive tomorrow IF I do not take unreasonable risks today. Is that a "belief" in the sense that someone believes God exists? Or is this 'belief' merely an estimation of chance? I am aware of enough close calls in traffic that IF I spent much more time bicycle riding around town, and IF I chose to ride on the freeway, I would have a greater chance of dying. I know that IF I ignore signs of disease, a fairly rapid death might ensue--maybe not by tomorrow, but sooner than December 1 (24 days away).

I don't believe the sun will rise in the east. I know the sun MUST rise in the east, given the mechanics of celestial bodies. It's not a belief. The sun has no choice.

About the gods I have beliefs and no knowledge. About Caesar Augustus I have more beliefs than solid knowledge. (I have no proof in my possession that he actually existed.) About Mayor Lattimer I have knowledge--proof positive. I don't believe he existed, I know he existed.

Our minds are full of things for which we have no evidence, but which we count as factual (like Caesar Augustus) because people we believe are trustworthy say he existed. I don't know that all the people who have said Caesar Augustus existed were trust-worthy. Are they more or less trustworthy than all the people who said God existed?

How can I say that most people are as trustworthy as I am (no more likely to fabricate historical events and entities than I am)? I say that because I believe it to be so. There is only some evidence that most people are trustworthy, and there is some evidence that most people can be, or are not trustworthy.

The foundations of my knowledge at least, seem to have at least layers of belief. I trust (an act of belief) that my teachers were not all lying. -

Is an armed society a polite society?About 1/3 of Americans own guns. In the 1970s it was around 1/2 of the adult population. Lets say there are 200 million adults (there are, roughly). About 65 million people own guns.

About 30,000 people are killed every year by firearms in the USA. The rate varies between 2 or 3 per 100,000 people in New England and the Upper Midwest to around 45 to 50 per 100,000 in the Deep South. 40% of people in Minnesota own guns, and 12% of Massachusetts people own guns. The rate of gun violence is very low in both states. Alabama and Mississippi both have gun ownership rates that are over 50%, and both have high rates of gun deaths. About 50% of North Dakotans own guns, and they have very low rates of gun violence.

The rate of gun deaths isn't very well correlated with gun ownership. Most people who own guns do not kill people. There must be something else that accounts for gun related deaths besides gun ownership. There is.

It's culture. People in some parts of the country (like the Deep South) are much more likely than New Englanders to take justice into their own hands. They are, apparently, more likely to feel insults to their honor, dignity, and so forth than are people in the Upper Midwest. People in the Deep South are more likely to distrust civil authority ("the government" they hiss) than people in New England.

Why?

Differences in religion, ethics, background, social morés, and so forth.

Puritans get a bad rap by a lot of people, but the Puritans considered civil society important, viewed the state as a an appropriate administrator of justice, and expected people to behave civilly and appropriately. Those values spread westward, and were strengthened by the influence of German and Scandinavian Lutheran immigration into the Midwest. More uptight, probably, but we kill far fewer people over trivial matters.

In the Deep South there has been a long standing preference for the Local against the Centralized authority of the state -- even their own state. (Before the civil war, southerns didn't build railroads across state lines for fear of the next state over interfering or benefitting.) They were individualists in a way that New Englanders weren't. Righteousness was a much more personal affair, and subject to personal interpretation. Couple this view of righteousness with suspicion of state authority, and you get a do-it-yourself approach to justice. You also get a more individualized kind of resentment against others. Wrongs must be righted, and if you wronged me, I will personally punish you (by shooting you, quite possibly).

Yes, sober Norwegian Lutherans in the north do occasionally kill each other, but at nothing like the rate the Baptists do down south.

So if all the guns and ammo were to disappear tomorrow, the rate of murder might not change all that much. The white southerners and the black sons of the south living in northern ghettos would continue to kill each other, with knives probably, at the same high rate as they do with guns. At least there would be fewer bystanders killed. -

China's 13th 5 year planNobody has anything to gain, really, by China failing. I do wonder, though, whether the predictions about their future may be overly optimistic. The maldistribution of age groups is a problem. Maintaining employment opportunities, along with householder opportunities, is essential if they are to maintain economic growth and social stability. They have some horrendous environmental problems (badly polluted air and water, among them) and climate change will make life difficult in parts of China. Their access to plentiful freshwater is problematic.

HERE is an article in the NYT about the long-term impact of the 1-child policy in China.

There should be, and is, some doubt about the veracity of China's economic figures. (One can, should, and ought to be skeptical about any state's economic reports, predictions, growth targets, and so on.)

A billion plus person economy should be able to float many boats. How long that will take, what the consequences will be locally and globally remains to be seen.

I've always thought a 5 year plan was a good idea. The USA would benefit from planning a ways out into future rather than expecting results every quarter. -

What is the point of philosophy?The point of science is to settle our curiosities about the world and make accurate predictions of the world.

So what about philosophy? — darthbarracuda

Science:

from Old French, from Latin scientia, from scire ‘know.’

and

Philosophy:

from Old French philosophie, via Latin from Greek philosophia ‘love of wisdom.’

There is clearly a difference between "know" and knowing-finding out-discovering, on the one hand and loving wisdom on the other. They are not opposed to each other, but they may not be complementary either.

There is a difference between "How are millipedes getting into my basement" and "Millipedes are welcome beasts at the feast of life." (Millipedes are vegetarians; centipedes are carnivorous. Apparently the centipedes are not eating the millipedes Why not? What are they eating, then? Clearly, the feast of life needs better management.)

Messing around with uranium to see if one can get a critical mass going is clearly a scientia, scire kind of thing. Something that guys do in the garage. Wondering whether one exists, and how one can tell, is not something guys do in the garage. That happens when the guy is alone, drinking beer, and cogitating with the help of cigarette smoke. (Cigarettes are peculiarly conducive to philosophical thinking. Exhaling smoke is existentially suggestive.)

Not all philosophers require beer and cigarettes of course. I have a feeling that Kant was the type that did without both, what with his Pietist upbringing. Sartre without cigarettes is unthinkable. Café au lait and cigarettes for Camus. -

Financial reportsWhat is needed is a reasonably steady income that over time meets, but does not greatly exceed, the cost of operation. Too much money at one time presents an odd problem. One might be a year ahead in income, but if one stops seeking donations, eventually the cash will be gone and people will be out of the habit of thinking about donating.

While I would rather not make monthly donations of $1 or $2 through a credit card, numerous smaller donations would add up to a more regular income than a few big donations. On the other hand, maybe not. Do small, two-bit donations require a disproportionate amount of time to process and record?

Here are some examples of banner lines that might help:

$12 donations and a banner "This week is brought to you by..." $50 donations, and "This month is brought to you by...

"Philosophy is free but space on this server costs $50 a month!"

"Had a free meal from your favorite restaurant recently? This month's serving cost $50."

"Talk is cheap but servers cost $50 a month."

"For $50 your pearls of wisdom will be preserved for your posteriori.

"Why spend $50 on a server when we could just write all this stuff on bathroom walls and toilet stalls?"

Pay walls generally impose limits on access; 5 free accesses per month, then blockage. That works when one is a known product and is in demand -- like the Wall Street Journal or New York Times are. It works for porn sites, too, but I don't think it would work for any philosophy site, ours or somebody else's.

Since 1 person is responsible for paying for the server, the site functionally if not in fact "belongs" to that person. If the site can and will be shut down if there is not enough money to pay for it, the site more functionally and in fact belongs to the donors. There is a stronger incentive to support the site if the donors own it, and will lose it if and when they do not support it.

I do think it is important to establish and maintain the principle that the site exists on the basis of regular, ongoing support. (On the other hand, "vaguely defined group ownership" can be problematic too.) Supposing Jamalrob gets run over by an ox cart and is no longer able to process donations and send checks. The site fizzles. Shoe string operations in the US sometimes incorporate as what are known as 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations. They are tax exempt and are governed (or advised, depending) by a community board. The boards are self-appointing after incorporation or they can be elected. -

History and RevisionismThey fit into 3 broad camps, the traditional view which is stated above, the revisionist view which is sceptical of the traditional one and thinks there were alternative reasons for dropping the bombs and also the middle view which stands somewhere between them. — shmik

A lot of the historians in the article are arguing that the narrative of the trade off between land invasion and atom bomb is just political spin. — shmik

Just about everything divides into three broad camps. Some people are vegans, some people eat only meat, and most people are somewhere in between. [B}Spin was from the beginning; is now, and ever more shall be, Spin without end. Amen.[/B]

We may at times be overly suspicious that politicians, generals, bankers, and everybody else are up to something other than what they appear to be doing.

History doesn't have a pre-ordained destination, but it quite often leaves pretty clear tire marks in the sand.It is possible that there was a devious plot to use the already enormous expenditures of WWII to pull off the very expensive effort to develop nuclear weapons, which the devious plotters knew would be really handy for World War III once WWII was over. Always one war ahead of the game. The weapon had to be demonstrated so that the Communist Menace would know we could fry them if they got in our way, and Japan merely offered a convenient place to do the demonstration. Nobody liked the Japs anyway, just then. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were therefore not bombed so there would be some nice fresh targets to incinerate, the better to scare the Communists with.

Truman faked any angst he would be expected to have had, had he needed to decide between atomic bombing or invasion. Roosevelt and Truman, of course, knew from the get go that Japan would fold and there would be no invasion. The invasion business was just spin. Part of The Plan. All this had been worked out by the White House, CIA, the Pentagon, and several slimy public relations firms in 1939. — Flat Out Fiction

The trajectory of events well before Pearl Harbor pointed towards a major conflict in the pacific. Japan really had embarked on an expansion of it's controlled territory, and this eventually put them in political, military, and economic conflict with the British, Americans, Russians, et al. Once the battle began, it was clear that the Allied objective would be the defeat -- not just the containment -- of the Axis powers. We succeeded, but that wasn't guaranteed.

"Knowing that the atomic bombing or an invasion of Japan was unnecessary" is writing history through a rear view mirror. Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon didn't know how the war in Vietnam was going to end. I'm sure they assumed we would win it, until it became clear that we wouldn't. Bush and Obama didn't know how their respective military offensives would turn out either. I'm sure they thought it would all go well by the end. After all, these were just two bit countries, how hard could it be?

Those who were against Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan didn't know how it would turn out either. In 1968 we may have chanted, "Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh/The NLF is going to win" but we had no more idea of what the future was going to look like than anybody else did.

The trajectory of events over the last 50 years points toward more wars by the United States (and its frequently not very enthusiastic allies) to hinder, contain, or crush local challenges to some regional status quo which threatens US hegemony. The next challenge might be in the Middle East, might be in Africa, might be in South America, might be in Asia, might be in Europe -- take your pick. Hopefully the next challenge won't come from Canada.

The trajectory of events also points toward little chance for any domestic movement to actually change US foreign policy.

One item in the global status quo that hasn't changed is the threat of nuclear weapons. The United States, Great Britain, France, Russia, China, Pakistan, India, North Korea, (and Israel, so I have heard) are so armed. All of the possessor nations also possess (or are perfecting) missiles capable of delivering atomic bombs to distant sites (not sure about Israel's missiles).

Nuclear weapons are another trajectory. Today the Union of Concerned Scientists' doomsday clock is at 3 minutes before midnight (It was 5 minutes before midnight in 2012). -

History and RevisionismWe know quite a bit about how the Manhattan Project was conceived and how it was executed. It cost about $2 billion plus 1945 dollars -- a small share of the USA's total $341 billion plus 1945 dollar expenditure for WWII. Roughly 130,000 people were employed, a majority of them technologically untrained women. It was a crash program requiring less than three years time, though civilian nuclear physics research had been underway for some time.

Germany was probably the initial intended target, but they were defeated in May, 1945. A plutonium was tested on July 16, 1945 and U235 and plutonium bombs were used on August 6 and 9th.

Discussions began in 1944 about how the war with Japan was to be concluded. There were at the time two or three alternatives (not including an atomic bomb which was still an unknown quantity). CIA Invasion of Okinawa and Kyushu and then a ground attack on Tokyo was one plan.

We don't need to know with complete certainty what the Joint Chiefs of Staff or the President or General Tojo and the Emperor of Japan were thinking in the summer of 1945. We know for certain that the war with Japan had been very costly, it was going to be over soon--one way or another--and it was ended.

There were tradeoffs to be made in the decision to invade, or not (from our side) and the decision to surrender, or not (from the Japanese side). No one could be sure at the time which course would be most favorable. -

What is the point of philosophy?Intellectual masturbation doesn't measure up to the real thing, so I'd advise against too much of it, just in terms of pleasure received per erg of labor.

Re: The Sciences vs. Philosophy

Is it the case, perhaps, that when philosophy spun off its various proto-scientific businesses, that a fair amount of philosophical practice went with them?

After all, it has been the case for quite some time that science has labored to find the truth about various things, like 'the cause of disease' or 'the motion of the planets'. True, they didn't arrive at any truths immediately, and neither did philosophy. But the search for [at least some of the] truths which philosophy embarked upon was achieved in its spin-offs--like biology and astronomy. Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546 published a work on "contagion" in which he discussed cause and effect in disease. He wasn't exactly on the mark with respect to specifics, but he did correctly theorize that disease was caused by agents, of some kind. He didn't know what those agents were, and it would take 300 more years before Pasteur, Lister, and Koch (et al) nailed down "germs" (bacteria) as the cause, and 20 years after Koch, viruses were identified as a cause of disease too.

Yes, very workmanlike labors were required. We knew what bacteria looked like (since the mid 1600s, a century after Fracastoro). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek made his own lenses (a skill he learned on his own--he was otherwise in the cloth/clothing/drapery business--which enabled him to see these "little beasties". He can't be faulted for not theorizing his way to the little beasties being the cause of the boil on his backside. That would be a leap too far. Koch (1876) published his Postulates in which he formalized how to identify the bacterial cause of a disease.

Viruses were discovered by passing the juice of diseased tobacco plants through porcelain filters and applying the resulting fluid to healthy tobacco plants. Voila! Bacteria left behind, something disease-making passed through. Tobacco phage virus discovered. Sounds simple, but some deep thought preceded the experiment (which probably didn't work the first time around). Soon after biologists discovered that a cancer of chickens could be caused by a virus too. Then they figured out how vaccinations worked, and what other diseases were caused by viruses (like chickenpox, smallpox, mumps, measles, herpes, etc.

You already all know about the WHO, WHEN, WHERE, WHY, AND THEN-WHAT of the motion of celestial bodies.

Less happily, but nonetheless impressively, the line of thinking which led to e=mc2 and on to the big KABOOM! in the desert of New Mexico required depth of thought -- deep deep depth, not just a shovel or two sized hole.

Yes, separating U235 from U238 was tedious workmanlike stuff involving very big magnets, Milled uranium ore—U3O8 or "yellowcake"—is dissolved in nitric acid, yielding a solution of uranyl nitrate UO2(NO3)2. Pure uranyl nitrate is obtained by solvent extraction, then treated with ammonia to produce ammonium diuranate ("ADU", (NH4)2U2O7). Reduction with hydrogen gives UO2, which is converted with hydrofluoric acid (HF) to uranium tetrafluoride, UF4. Oxidation with fluorine yields UF6. During nuclear reprocessing, uranium is reacted with chlorine trifluoride to give UF6: U + 2 ClF3 → UF6 + Cl2.

All very workmanlike.

Chemists began theorizing about how atoms and molecules fit together and interacted long, long before they would ever see anything like an electron microscope image of atoms or molecules.

Philosophers asked "what is matter?" Chemistry and physics provided the answer. Philosophers might not like it that we now know that a brick is made up of molecules and molecules are made up of atoms and atoms are made up of sub-atomic particles like the Higgs Boson, and perhaps...

Philosophers asked "What is "mind" and where is it?" It seems like a waste of time for philosophers to now diddle around with speculation that maybe mind is somewhere else other than between the ears. We know, for a fact, that if you start scooping out bits and pieces of the soft, fatty gelatin-textured, grayish pink brain, the "mind" starts going haywire in short order. A scoop here, and the person can no longer recognize language. A scope there and the person can recognize, but not generate language. A scope back there and vision begins to dis-integrate. The unfortunate subject might start seeing horizontal lines instead of whole images. Snip a bit of the brain stem out and the person will be unable to wake up -- since that little snipped piece wakes us up in the morning and puts us to sleep at night.

Keep scooping out bits and pieces and before long the mind, and the person who was represented by it have disappeared forever.

Maybe ideas exist in the ether and maybe we get our bright ideas by intersecting with a cloud of potent abstractions floating about, but if philosophers can't come up with some sort of evidence of the truth of that idea, then they should follow the practice of their workmanlike offspring and dispense with the idea altogether.

Philosophers search for truth, and Philosophy spawned the means of finding at least a good many truths. "Truth" itself is a nonentity like "Good". Nowhere in the universe is there a pile of "truth" and "good" waiting to be discovered, so stop talking about it that way.

Some things remain open to useful discussion. What is a "good life"? There isn't any final answer to the question, because it depends on the specifics of one's situation. The richest people in the world have children. Bill and Melinda Gates' children face a different "good life" problem than someone who is born with quite average intelligence, no inheritance, and no bright opportunities spread before them. Both groups of children can live lives of extraordinary goodness, but the details of their lives will be very different.

"What should I do?" and "What is it reasonable to hope for?" are also fruitful topics. Everyone benefits from thinking about what actions are meet, right, and salutary. People are well advised to NOT hope for a lottery win. Not only is it immensely unlikely, but it often brings little happiness to the winners, who are not at all prepared to be millionaires. (I'm ready, willing and able--with plans for spending $100 million--after taxes--but I never buy tickets, so... it's not very likely I'll win.)

BC

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum