-

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusIf so this itself would be an illustration of a "psychological theory" that goes beyond simply "acquaintance" (showing) the object, thus refuting that "acquaintance" or "showing" is where it must stop. — schopenhauer1

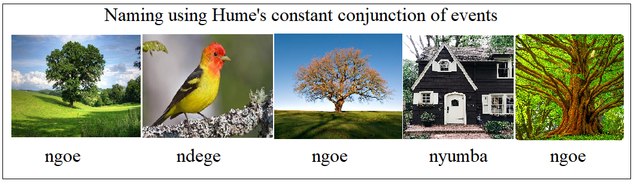

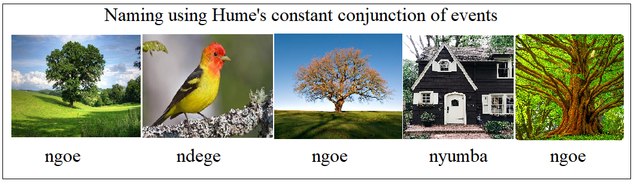

I agree that explaining how the mind can learn the meaning of the world "ngoe" from just five pictures is beyond my pay grade. All I know is that it works, and is in principle very simple.

The Tractatus only begins after I have learnt the word "ngoe", and only then, does the word "ngoe" in language mirror the "ngoe" in the world. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatus'Object' is a pseudo-concept. A particular object is not. — Fooloso4

'Object' is a pseudo-concept because it says nothing about what is the case, not because it makes up the substance of the world. — Fooloso4

Right, but the issue is whether something that falls under a pseudo-concept is a pseudo-concept. — Fooloso4

Tractarian objects are pseudo-concepts

Introduction - "This amounts to saying that “object” is a pseudo-concept. To say "x is an object" is to say nothing".

Why is a Tractarian object a pseudo-concept? Things can be said about concepts proper, such as book and tables, but things cannot be said about Tractarian objects because they are simples. They are pseudo-concepts because they are simples.

2.02 "Objects are simple"

Why are Tractarian objects simples? If they weren't simples, propositions could not picture the world.

2.021 "Objects make up the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite

2.0211 "If the world had no substance, then whether a proposition had sense would depend on whether another proposition was true

2.0212 "In that case we could not sketch any picture of the world (true or false)

2.023 "Objects are just what constitute the unalterable form"

Therefore as Tractarian objects (ie, pseudo-concepts) are simples (ie, indivisible), there cannot be anything that falls under them.

===============================================================================

Formal concepts are pseudo-concepts. — Fooloso4

Tractarian objects are pseudo-concepts

Introduction - "This amounts to saying that “object” is a pseudo-concept. To say "x is an object" is to say nothing".

The proposition "x is a horse" is a concept proper and the proposition "x is a number" is a formal concept.

(Spark notes Propositions 4.12 – 4.128)

Examples of propositional variables could be: "the sky is blue", "the sky is purple", "grass is green", "grass is orange".4.127 "The propositional variable signifies the formal concept"

Being propositional variables, each has the value either true or false.

In the truth table, "the sky is blue" is true, "the sky is purple" is false, "grass is green" is true, "grass is orange" is false.

Therefore the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept.

What does Wittgenstein mean by formal? He refers to formal relations, which are logical relations between objects. He refers to formal properties, which are internal and logical. Formal means logical.

4.122 "In a certain sense we can talk about formal properties of objects and states of affairs, or, in the case of facts, about structural properties: and in the same sense about formal relations and structural relations. (Instead of "structural property" I also say "internal property": instead of "structural relation", "internal relation")

The variable name x signifies a pseudo-concept object

4.1272 "Thus the variable name "x" is the proper sign for the pseudo-concept object. Whenever the word "object" ("thing". etc) is correctly used, it is expressed in conceptual notion by a variable name"

On the one hand the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept and on the other hand the variable x signifies a pseudo-concept object. Therefore, a formal concept cannot be a pseudo-concept. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThat depends on the medium of representation, whether what is being pictured is intended to communicate something to someone else, and what it is that is being represented............2.1 "we picture facts to ourselves" — Fooloso4

If we were only picturing facts to ourselves, then we are using a Private Language, which Wittgenstein in Philosophical Investigations said was not possible.

Even if we were picturing facts to ourselves, we would have to make the conscious choice whether i) the red in the model is picturing the red in the world or ii) the wood in the model is picturing red in the world.

If that were the case, a picture wouldn't be a model of reality, a picture would be a model of an individual's conscious decisions.

2.12 "A picture is a model of reality" -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusJust as the car does not become the bicycle, it is necessary that whatever it is the represents the car in the picture does not become something else. — Fooloso4

In the model is a red piece of wood, and in the world is a red car.

From the Picture Theory, the red piece of wood in the model pictures the red car in the world.

But how do we know, just from the picture itself, whether i) the red in the model is picturing the red in the world or ii) the wood in the model is picturing red in the world?

From the picture itself, we cannot know. We need someone to come along and tell us which is the case i) or ii), and if that happens, this destroys the Picture Theory, which is meant to stand alone. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusCertainly, this could lead to a regress (definitions of definitions of definitions)....................Surely I can point to these processes that account for object formation in the mind, and how we attach meaning to objects. — schopenhauer1

As I see it, some words we learn by description and some by acquaintance.

As regards learning by description, we can go to the dictionary and discover that a "tree" is defined as "a woody perennial plant having a single usually elongate main stem generally with few or no branches on its lower part". But then we have to look up the definition of "woody" and end up in an infinite regress.

Sooner or later, we have to learn words by acquaintance, as illustrated in the picture below. As the Tractatus notes, I cannot describe the meaning of "ngoe", I can only show it. Though I agree that this is not the same approach as laid out in the Tractatus.

What do you think "ngoe" means, now you have been "shown" the picture? -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatus'3' signifies the value of the concept number. A particular number falls under the concept number in a way analogous to 'table' falling under the concept 'object'. That does not mean that 'table' is a pseudo-concept. — Fooloso4

There are two kinds of objects, concepts proper and pseudo-concepts. There are

concepts proper in our ordinary world, such as "furniture", and there are pseudo-concepts in the Tractarian world, of which the variable x is the proper sign.

In our ordinary world, a "table" is a particular instantiation of the concept proper "furniture". However it is also the case that "a table" is another concept proper, which mat be instantiated in its turn.

In our ordinary world, something that falls under a concept proper can also be a concept proper. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusWittgenstein seems to not care to discuss mind, but language limits. — schopenhauer1

For Wittgenstein, thought was language and language was thought. I may disagree, but that seems to be his position. As he said, the limits of my language is the limits of my world.

Notebooks 1914-16 – 12/6/2016 – page 82.

===============================================================================Now it is becoming clear why I thought that thinking and language were the same. For thinking is a kind of language. For a thought too is, of course, a logical picture of the proposition, and therefore it just is a kind of proposition.

If signs are not signifying a possible states of affairs, they are not picturing anything, and thus cannot be communicated with any sense. — schopenhauer1

Within the Tractatus, an elementary proposition pictures a state of affairs. The state of affairs pictured may or may not obtain. If there were no states of affairs to picture, then there would be no elementary proposition. It seems that one important feature of the Tractatus is in developing the modal idea of possible worlds, allowing us to talk about non-existent things, such as Sherlock Holmes and unicorns. This was something Bertrand Russell had trouble with, how to think of something that doesn't exist. For Wittgenstein, the problem goes away, as objects always exist, and only their combinations change. This allows the mind to move between actual and possible worlds .

===============================================================================

1 +1 =2 is not derived from empirical evidence, but as a functioning of how numbers work — schopenhauer1

For Wittgenstein in the Tractatus, there is no synthetic a priori. We cannot know "grass is green " or "1 + 1 = 2" prior to observing the world. Our only knowledge comes from observation. We have no analytic a priori knowledge. The Tractatus is an Empiricist Theory.

I disagree, but that is the Tractatus.

The Picture Theory is limited to elementary propositions mirroring states of affairs in the world. However, "1 + 1 = 2" is only the logical part of an elementary proposition, not a representative part of an elementary proposition. The logic of "1 + 1 = 2" in language is mirrored by the logic of 1 + 1 = 2 in the world as a state of affairs.

There is no temporal consideration, in that knowing "1 + 1 = 2" in language is contemporaneous with 1 + 1 = 2 being the state of affairs in the world.

Personally, as I believe that the world is fundamentally logical - in that one thing is always one thing, if thing A is to the left of thing B then thing B is to the right of thing A and if event C happens after event D then event D happened before event C - then if language mirrors the world, then language also will be fundamentally logical.

I think that the Picture Theory is fundamentally flawed, in that it leads to as you say "an infinite regress", but that is another matter.

===============================================================================

Surely I can point to these processes that account for object formation in the mind, and how we attach meaning to objects — schopenhauer1

From Wittgenstein’s Picture Theory of Meaning by Christopher Hurtado

The picture theory of meaning was inspired by Wittgenstein’s reading in the newspaper of a Paris courtroom practice of using models to represent the then relatively new phenomenon of auto-mobile accidents (Grayling 40). Toy cars and dolls were used to represent events that may or may not have transpired. In the use of such models it had to be stipulated which toys corresponded to which objects and which relations between toys were meant to represent which relations between those objects (Glock 300).

Yes a red toy car can picture a real red car, but the flaw in the Picture Theory is the statement "had to be stipulated", which has to happen outside the Picture Theory.

Suppose in the world is a red car, a blue bicycle and a green truck. Suppose in the model is a red piece of wood, a blue piece of metal and a green piece of marble.

The Picture Theory assumes that the red piece of wood pictures the red car, the blue piece of metal pictures the blue bicycle and the green piece of marble pictures the green truck. But why should this be so?

Why cannot it be the case that wood pictures a truck, metal pictures a bicycle and marble pictures a car?

Or perhaps red in the model pictures a distance of 3 metres, blue in the model pictures a distance of 5 metres and green in the model pictures a distance of 10 metres.

There is no necessity that a red piece of wood pictures a red car, and yet the Picture Theory depends on this unspoken necessity, which seems to me to be a fundamental flaw in the Picture Theory.

IE, I agree that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason makes more sense than Wittgenstein's Tracatus, although the Tractarian idea of modal worlds is very important in philosophy.

(Kyle Banick - Necessity and Contingency - YouTube) -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThat was what I said, that numbers (or rather equations) are formal concepts because they are not abouts states of affairs of the world. Again, Kant is informative here, it is an analytic a priori statement. — schopenhauer1

Kant knows "1 + 1 = 2" prior to observing the world.

For Wittgenstein's Picture Theory, elementary propositions mirror states of affairs in the world

4.21 "The simplest kind of proposition, an elementary proposition, asserts the existence of a state of affairs.

The Tractatus is saying that the logical part of the proposition "1 + 1 = 2" in language mirrors the logical part of the state of affairs 1 + 1 = 2 in the world.

One difference between Kant and Wittgenstein is that Wittgenstein's Picture Theory in the Tractatus does not engage with the possibility of knowing that 1 + 1 = 2 prior to observing the world (as I understand it). -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusWhy is "One is a number" a formal concept and "1 + 1 = 2" not a "formal concept"? — schopenhauer1

In the Tractatus, there seem to be formal concepts and pseudo-concepts. Pseudo-concepts are the objects which are necessary for the substance of the world. The rest is logic, which cannot be described but must be shown.

I think that the propositions "one is a number" and "1 + 1 = 2" should be treated in much the same way, as being part of the logical structure. Numbers are not objects.

As Bertrand Russell writes in the Introduction

"It follows from this that we cannot make such statements as “there are more than three

objects in the world”.................the proposition is therefore seen to be meaningless.........We can say............“there are more than three objects which are red”"

Numbers are not Platonic Forms that remain after the objects have been removed. Numbers play their part in the logical structure, not in providing any substance to the world. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusWhat falls under a formal concept is not another formal concept..................If '3' was a formal concept then every number would be a formal concept. — Fooloso4

Mathematical equations are pseudo-proposiitons , but this does not mean the equation is a concept, either proper or formal. 1+1=2 is not concept, it is a calculation. — Fooloso4

'Number' is the constant form. 1, 100, and 1,000 are variables that have as a formal property this formal concept. — Fooloso4

The Tractatus mentions three kinds of concepts: formal concept, concept proper and pseudo-concept.

Formal concepts

The logic that ties elementary propositions together and states of affairs together cannot be described but can only be shown.

4.1272 "The same applies to the words "complex", "fact", "function", "number" etc. They all signify formal concepts"

4.1274 "To ask whether a formal concept exists is nonsensical"

Pseudo-concepts

Nowhere in the Tractatus does Wittgenstein describe what an object is, other than they are necessary for the substance of the world. Objects are pseudo-concepts.

4.1272 "This the variable name x is the proper sign for the pseudo-concept object.

Concepts proper

Concepts proper are things in ordinary language such as apples, tables and books

4.126 "the confusion between formal concepts and concepts proper"

Two types of elementary propositions can be considered, Tractarian and ordinary language. Problems arise when ordinary language elementary propositions are used to illustrate Tractarian elementary propositions.

Ordinary language elementary propositions

Ordinary language elementary propositions must include both formal concepts and concepts proper, such as "grass is green", where "grass" and "green" are objects and "is" provides the logical structure.

Tractarian elementary propositions

Tractarian elementary propositions must include both formal concepts and pseudo-concepts.

Elementary propositions mirror states of affairs in the world

4.21 "The simplest kind of proposition, an elementary proposition, asserts the existence of a state of affairs.

For example, in the elementary proposition "F (x)", x is the sign for the pseudo-concept object. F is the sign for the internal property of x, and as an internal property is a necessary part of the object x. As objects are pseudo-concepts, then F is also a sign for a pseudo-concept. The logic is shown in the function F (x) itself, signifying a formal concept.

Properties are internal if necessary to the object

4.123 "A property is internal if it is unthinkable that its object should not possess it"

4.124 "The existence of an internal property of a possible situation is not expressed by means of a proposition: rather it expresses itself in the proposition representing the situation, by means of an internal property of that proposition".

As Bertrand Russell writes in the Introduction, objects can only be mentioned in connexion with some definite property

"Objects can only be mentioned in connexion with some definite property."

"It follows from this that we cannot make such statements as “there are more than three

objects in the world”.................the proposition is therefore seen to be meaningless.........We can say............“there are more than three objects which are red”"

The number 3

There is the universal concept of number and there are particular numbers, such as 3.

Number is described as a formal concept.

4.1272 "The same applies to the words "complex", "fact", "function", "number" etc. They all signify formal concepts"

4.126 - "When something falls under a formal concept as one of its objects, this cannot be expressed by means of a proposition. Instead it is shown in the very sign for this object. (A name shows that it signifies an object, a sign for a number that it signifies a number, etc.)"

Objects are pseudo concepts because they exist in the world and make up the substance of the world. Mathematical equations, which show the logic of language and the world, are, as you say "a logical method", and as part of the logical method are formal concepts.

As the Tractatus uses the term pseudo-proposition in a negative way, mathematical equations cannot be pseudo-propositions

4.1272 "Whenever it is used in a different way, that is as a proper concept-word, nonsensical pseudo-propositions are the result"

5.535 "This also disposes of all the problems that were connected with such pseudo-propositions"

6.22 "The logic of the world, which is shown in tautologies by the propositions of logic, is shown in equations by mathematics.

What is the number 3 in the Tractatus? It cannot be a pseudo-concept as it doesn't exist as part of the substance of the world. It should be treated as any other logical function, such as "and", "or", "if" or "then", which make up the fabric of logical structure, and are formal concepts.

Logical constants don't represent, but show.

4.0312 "My fundamental idea is that the "logical constants" are not representatives; that there can be no representatives of the logic of facts."

The number 3 is a sign that signifies a number. Numbers are formal concepts. Therefore, the number 3 is a sign that signifies a formal concept, in the same way that the logical constant "and" also signifies a formal concept.

4.126 "A name shows that it signifies an object, a sign for a number that it signifies a number, etc"

4.1271 "For every variable represents a constant form that all its values possess, and this can be regarded as a formal property of those values."

IE, within the Tractatus, the number 3 cannot be a pseudo-object as it doesn't make up the substance of the world, but because it is part of the logical structure of both elementary propositions and state of affairs, it must be, as with all particular numbers, and as with all logical constants, a formal concept. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusYes, but Kant would simply classify it as analytic a priori. It is a truth that can be grasped through purely reasoning and not experience (equivalent to Wittgenstein's "state of affairs in the world"). But I am perplexed why with all this epistemological history he could have drawn from, he ignores it. — schopenhauer1

It has been said that Wittgenstein never studied philosophy as such, although he may have learnt from certain other philosophers he was in direct contact with, such as Bertrand Russell. So he did ignore epistemological history as he was not interested in the history of philosophy as a field of knowledge.

There may be a difference between Kant's analytic a priori and Wittgenstein's formal concept, in that Kant's analytic a priori is knowledge prior to any knowledge about the world, whereas Wittgenstein's formal concept straddles on one side language and thought and on the other side the world.

4.1272 - "The same applies to the words "complex", "fact", "function", "number" etc. They all signify formal concepts"

4.1274 "To ask whether a formal concept exists is nonsensical"

6.22 "The logic of the world, which is shown in tautologies by the propositions of logic, is shown in equations by mathematics.

In the Tractatus, the formal concepts existing in language, which cannot be described but only shown, are mirrored by formal concepts that also exist in the world

4.21 - "The simplest kind of proposition, an elementary proposition, asserts the existence of a state of affairs.

IE, for Kant, the analytic a priori exists prior to any knowledge of the world, whereas for Wittgenstein the formal concepts in language are mirrored by formal concepts in the world. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThus, it seems to be the case for Witt’s theory, 1 + 1 = 2 is formal as it is not a state of affairs per se, but a description of a category of sets that may occur as a state of affairs. It’s a description of a class not of a particular state of affairs that could be true or false. — schopenhauer1

As the elementary proposition "1 + 1 = 2" asserts the existence of a state of affairs, the logical structure of the elementary proposition "1 + 1 = 2" must be mirrored in the state of affairs.

As numbers are formal concepts, I think I am right in saying that Wittgenstein would call this proposition meaningless. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatus(4.12721) "A formal concept is given immediately any object falling under it is given. It is not possible, therefore, to introduce as primitive ideas objects belonging to a formal concept and the formal concept itself. So it is impossible, for example, to introduce as primitive ideas both the concept of a function and specific functions, as Russell does; or the concept of a number and particular numbers." — Fooloso4

As I understand it, a proposition cannot express a formal concept, ie the logical structure of the proposition, but it can only be shown by the proposition.

From Bertrand Russell on Something by Landon D.C. Elkind

In their monumental Principia Mathematica, Russell and his co-author Alfred North Whitehead attempted to create a logically sound basis for mathematics. In it their primitive proposition ∗9.1 implies that at least one individual thing exists. It follows that the universal class of things is not empty. This is stated explicitly in proposition ∗24.52. Whitehead and Russell then remark: “This would not hold if there were no instances of anything; hence it implies the existence of something.” (Principia Mathematica, Volume I, 1910, ∗24). Here then, logic seems committed to the existence of something.

Whereas the early Bertrand Russell thought that a pure logical structure wasn't possible, Wittgenstein believed that a pure logical structure, one of formal concepts, was possible.

IE, 4.12721 is saying that the concept of a number and particular numbers cannot be primitive but are both formal concepts.

===============================================================================

If, however, I say: "There are three horses" then the number of horses is not expressed as the variable 'x', which could mean any number of horses, but as '3'. — Fooloso4

I could say "there are 3 horses".

As the number 3 cannot be described but only shown, this makes it a formal concept.

For Wittgenstein, numbers are not objects having Platonic Form that can be described in the absence of the horses that they are quantifying. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusI think Wittgenstein is saying that an "object" like the number 1 has a sense if it is an object or a description. — schopenhauer1

From Bertrand Russell's Introduction:

It follows from this that we cannot make such statements as “there are more than three objects in the world”, or “there are an infinite number of objects in the world”. Objects can only be mentioned in connexion with some definite property. We can say “there are more than three objects which are human”, or “there are more than three objects which are red”

3.1431 The essence of a propositional sign is very clearly seen if we imagine one composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs and books) instead of written signs. Then the spatial arrangement of these things will express the sense of the proposition.

It seems that an object like the number1 is a formal concept, and being a formal concept, can never be the sense of a proposition and can never be described by a proposition, but only shown. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusSee 4.12721. The concept of a number is a formal concept. Particular numbers are not. They fall under the concept of a number. — Fooloso4

4.1272 "The same applies to the words "complex", "fact", "function", "number", etc - They all signify formal concepts............."1 is a number", "There is only one zero" and all similar expressions are nonsensical

Why do you think that particular numbers, such as the number 1, are not formal concepts? -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatus@Fooloso4

I now no longer believe that the x in F (x) is a formal concept, but in fact represents a concept proper.

A formal concept defines how the variables "T" and "x" are to "behave" or perhaps a better way to say it, is how they are to be understood. These aren't like "proper concepts", such as "red", "hard", etc. which settles the external properties of complex objects. — 013zen

Consider the proposition "grass is green".

If x = grass satisfies the function Green (x) then Green (x) is true.

Where grass and green are "concepts proper" (4.126)

From 4.12, a proposition can represent concepts proper, such as grass and green, but cannot represent logical form, ie "formal concepts" (4.126). A proposition can only "show" (4.121) logical form.

So, within the proposition "grass is green", where is the logical form? The logical form of the proposition must be shown by the word "is", which is a relation between concepts proper. For Wittgenstein, unlike Frege, relations are not object. Relations have no existence other than relating concepts proper, in that if the concepts proper were removed, no relation would remain as some kind of Platonic Form.

As the concept "is" can only be shown and not represented, it is a formal concept rather than a concept proper.

Similarly within the function Green (x), where is the logical form? The term "Green" infers the expression "is green", where "is" is the formal concept and green is the concept proper.

For both the proposition "grass is green" and the function Green (grass), in the first the formal concept "is" is explicit and in the second the formal concept "is" is inferred. The concepts proper remain grass and green.

===============================================================================

We cannot, for example, input a proper number to which corresponds the formal concept of number for say, a simple object. — 013zen

A concept proper cannot be a number.

From 4.0312, "logical constants" such as “and,” “or,” “if,” and “then” are not representatives. This makes sense, in that logical constants are not Platonic Forms.

Suppose there is a horse in a field and another horse enters the same field. We can say "horse AND horse". But if one horse left the field, the AND would not remain in the field as some kind of Platonic Form. AND only exists in the relationship between two concepts proper.

3.1432: We must not say, “The complex sign ‘aRb’ says ‘a stands in relation R to b;’” but we must say, “That ‘a’ stands in a certain relation to ‘b’ says that aRb.”

Similarly, we could "horse 2 horse". But if one horse left the field, the 2 would not remain in the field as some kind of Platonic Form. Numbers only exist in the relationship between two concepts proper.

As numbers only exist in the relationship between concepts proper, and relations in the Tractatus are not objects, they are formal concepts.

===============================================================================

So, while we can say: "There are two red fruits" this analyzes into:

∃x(P(x)) ∧ ∃y(P(y) ∧ (x≠y)) There is no sign corresponding to the formal concept "number" despite what appears to be a number presented in the proposition. — 013zen

However, isn't it the case that the logical symbol ∧ (which means AND), is where number is introduced into the expression. For example, "horse AND horse" by its very nature has introduced the concept of number, in that if I wanted to explain the concept of the number 2 to someone, I could say either "horse ∧ horse" or "horse AND horse" and then show them the field with 2 horses in it. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusAn unhappy apple is an illogical proposition not an illogical object. An apple on the table or inside the sun is not a combination of objects it is a relation of the objects apple and table (on) or apple and sun (in). — Fooloso4

An object in logical space must be a logical object, meaning that its necessary properties must be logical. For example, if an apple was a logical object in logical space, it would have the necessary properties such as weight, colour and taste. An apple having the necessary property of happiness would not be a logical object.

In a state of affairs, objects are combined, necessitating a relation between them.

3.1432 – Instead of "The complex sign "aRb" says that a stands to b in the relation R", we ought to put "That "a" stands to "b" in a certain relation says that aRb"

===============================================================================

I don't know if you are attempting to interpret the Tractatus or argue against it. He makes a distinction between proper concepts such as grass and formal concepts such as 'simple object'. — Fooloso4

There are proper concepts such as "grass" and formal concepts such as the variable "x".

Wittgenstein in the Tractatus never explains what a simple object is, other than there must be simple objects, and that they must exist necessarily not contingently.

As states of affairs exists in logical space, and a state of affairs is a combination of objects, this means that these objects exist in logical space. An object existing in logical space infers that it it is a logical object.

I'm suggesting that in the expression "grass is green" is true iff grass is green, objects such as grass are not referring to actual objects, which are divisible, but must be referring to logical objects, which can be indivisible, and are simples.

===============================================================================

Book is not a formal concept. — Fooloso4

I agree. The variable x is the formal concept, not the book. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThere are no ‘logical objects’ (4.441) — Fooloso4

The expression "logical objects" may be read in two ways. It can be referring to either 1) objects that are logical or 2) logic can be an object.

As regards sense 1), in logical space are objects in combination. In order for this to be the case, these objects must be logical and their combinations must be logical. For example, a blue apple is a logical object, whilst an unhappy apple is not a logical object. An apple on top of a table is a logical combination, whilst an apple inside the sun is not a logical combination.

As regards sense 2), Frege treated relations and universals as objects. FH Bradley in treating a relation as an object concluded that relations don't ontologically exist in the world. Wittgenstein disagrees with Frege, and concludes in 4.441 that "There are no logical objects". This means in particular that relations, such as "to the left of " or "on top of" logical cannot be treated as objects, and in general that logical form, such as i) all H are M ii) S is H iii) therefore, S is M is not an object, in the sense that "grass" is an object.

===============================================================================

As part of a propositional analysis apples and tables can function as simples. — Fooloso4

Apples and tables as names in a proposition are concepts. Some think that concepts are simples, including myself, and fall within the theory of Conceptual Atomism.

From the SEP article on Concepts

Conceptual atomism is a radical alternative to all of the theories we’ve mentioned so far is conceptual atomism, the view that lexical concepts have no semantic structure (Fodor 1998, Millikan 2000). Conceptual atomism follows in the anti-descriptivist tradition that traces back to Saul Kripke, Hilary Putnam, and others working in the philosophy of language (see Kripke 1972/80, Putnam 1975, Devitt 1981).

If concepts weren't simple, when we thought of a concept such as grass as a set of other concepts, such as a low green plant, we would have to think of each of these concepts, such as a plant, as a set of other concepts, such as a living organism. But sooner a later a concept must be a simple otherwise our thought would be never-ending.

Therefore, thought requires that some concepts must be simples.

In the Tractatus picture theory, a proposition such as "grass is green" pictures the state of affairs grass is green.

The state of affairs grass is green exists in a logical space.

As concepts can be simples, the concept "grass" could be a simple, and as words such as "grass" logically picture an object such as grass existing in a logical space, this suggests that objects such as grass are also simples.

It is true that actual grass is divisible, for example into the top of the blade of grass and the bottom of the blade of grass, but objects aren't actual objects but rather logical objects, and logical objects such as grass can be simples.

Ir objects such as grass are not actual objects but logical objects, then logical objects such as grass can be simples.

===============================================================================

At 4.126 Wittgenstein introduces the term "formal concepts". — Fooloso4

In the function T (x), where T is on a table, the function T (x) is true if the variable x satisfies the function T (x). For example, T (x) is true if the variable x is a book.

As I understand it, the variable x is what Wittgenstein is defining as a formal concept.

4.126 (I introduce this expression in order to exhibit the source of confusion between formal concepts and concepts proper, which pervades the whole of traditional logic)...................so the expression for a formal concept is a propositional variable in which this distinctive feature alone is constant.

4.127 The propositional variable signifies the formal concept, and its values signify the objects that fall under the concept.

4.1271 – Every variable is the sign for a formal concept

4.1272 Thus the variable name "s" is the proper sign for the pseudo-concept object. -

Counter Argument for The Combination Problem for Panpsychismwe have observed that physical processes can form complex objects without human intervention, such as trees — amber

Some think that relations don't exist outside the human mind, in which case there cannot be complex objects outside the mind.

From Wikipedia – Relations (Philosophy) -

Eliminativism is the thesis that relations are mental abstractions that are not a part of external reality.

Do we observe a complex object because the object is complex or because we think the object is complex.

How to avoid the circularity of a human observing something that is independent of being observed? -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusTrying to make sense of the Tractatus from the useful conversation between @schopenhauer1 and @013zen:

A picture theory, however, would allow speculation, as long as you’re positing possibilities that logically follow from experience — 013zen

If I see a shadow I picture a shadow, and have learnt nothing, because I am picturing a picture. This leads to the problem of infinite regress, what pictures the picture.

However, as you say, if I picture a shadow, from past experience I can picture possible causes of the shadow, such as a cat, or a horse, or a cloud. Though none of these pictures of possible causes by themselves can tell me the true cause, for that I need further observations. If from further observation I do see a picture of a cat and not a picture of a horse or a cloud, then I can infer that the cause of the shadow was in fact a cat.

IE, it is not possible to learn from a picture of reality, but it is possible to learn from pictures of possible realities.

===============================================================================

I can't think of an object in space without a shape — 013zen

Within the Tractatus an object is indivisible, a simple.

This is not what the Neutral Monist thinks of an object, a simple. They think of an elementary particle such as a fermion or boson. This is not what the Indirect or Direct Realist thinks of an object, as for them an object such as an apple can be divided into the top of the apple and the bottom of the apple.

However, if the apple is thought of as a logical object, then it can be indivisible, simple, and as a logical object it can exist in a logical space. But where does this logical space exist?

The outside world is inherently logical, in that one thing is always one thing and if thing A is to the left of thing B then thing B is to the right of thing A. If the mind pictures a logical outside world then it follows that the picture in the mind will also be logical.

Noting, however, that the logical relation in the outside world between thing A and thing B is not the same as any ontological relation between thing A and thing B.

Logical objects in logical space puts a limit on what is possible, in that because one thing being two things is not logical it is not possible. Only logical objects are possible. Logic puts a limit on what is possible.

Objects such as apples and tables as logical objects are possible and therefore simples. Relations such as to the left of, taller than, heavier than or on top of as logical relations are possible and therefore simples.

A logical object can only exist in a logical space. Within this logical space exist other logical objects. This means that a logical object cannot exist in the absence of other logical objects. The consequence is that each logical object exists in some combination with other logical objects. A logical object in combination with another logical object is called a "state of affairs".

Between each logical object and all other logical objects are possible states of affairs

If within this logical world are logical possible states of affairs, and the mind can picture this world, then the mind in picturing logical possible states of affairs of necessity also becomes logical.

4.112 “Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts.” -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusIt is exhausting to have philosophers not explain themselves well..................I think Wittgenstein has just particularly been mythologized. — schopenhauer1

Perhaps Wittgenstein didn't think of himself as a philosopher, and was working out his ideas more for himself than others. A kind of conversational research with himself.

There are philosophers that I respect such as Kyle Banick who do say that Wittgenstein had "big ideas", so perhaps Wittgenstein deserves to have been mythologized, even if that wasn't what he wanted himself. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThe problem here is where Schopenhauer (and previously Leibniz) actually laid out their reasoning for their premise and built a foundation, Wittgenstein simply asserts it to build his linguistic project of atomic facts and propositions that can be stated clearly. — schopenhauer1

Wittgenstein uses an apodictic style

On the one hand, considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, and on the other hand, the Tractatus is notorious for its interpretative difficulties.

(SEP – Ludwig Wittgenstein)

On the one hand, the Tractatus employs an austere and succinct literary style. The work contains almost no arguments as such, but rather consists of declarative statements, or passages, that are meant to be self-evident, and on the other hand, the Tractatus is recognized by philosophers as one of the most significant philosophical works of the twentieth century.

(Wikipedia Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

A proposition may have value even if the words are ambiguous

It makes sense to say that what is important in the world are facts (objects in combinations) rather than objects, even if no-one can agree what an object is, and no-one can agree how objects combine.

IE, the statement "what is important in the world are facts (objects in combinations) rather than objects" has a value that everyone may agree with, even though there is no agreements as to what "object" and "combination" actually mean.

Similarly, everyone may agree with the statement "in the world postboxes are red", even if the Indirect Realist and Direct Realist don't agree where exactly does this world exist.

Even though the Tractatus uses a didactic style, everyone may agree that the remarks are of value, even if everyone disagrees with what the remarks actually mean.

Where is the value in the Tractatus

The question is what substantive philosophical lessons can we extract from the Tractatus. According to Facts, Possibilities, and the World. Three Lessons from the Tractatus, Hans Sluga:

One is the concept of fact, on which Russell and the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus relied so much, is philosophically brittle and that we must turn our attention, instead, to the broader notion of the factuality of the world.

Two is that we can and must think about the world in both factual and modal terms but that in doing so we must treat the idea of possibility, not that of necessity, as primary and we must conceive of possibilities as merely virtual, not as factual.

Three is that we must consider the world as a whole, if we are to make sense of logic, science, and ethics.

However, I need to research this further. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusEdit to add — Paine

I'm sure you probably already know, but the edit facility is quite useful.

At the bottom of one's own post - left clock on three dots - left click on edit - make changes to text - save comment. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusAt any rate, I agree with, like 90% of your post. Its just specifics we differ on, right now. — 013zen

Conversational research. As the architect Louis Kahn said "The street is a room by agreement". -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusOne can say that he is castigating all the metaphysicians and epistemologists that came before. — schopenhauer1

I, actually, take Wittgenstein to be attempting to break away from this tradition (epistemology and metaphysics) — 013zen

Perhaps the following is relevant.

It may not be the case that Wittgenstein was trying to break away from the tradition of epistemology and metaphysics, but rather that he didn't know much about the tradition in the first place. From IEP Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889—1951)

His early work was influenced by that of Arthur Schopenhauer and, especially, by his teacher Bertrand Russell and by Gottlob Frege, who became something of a friend.

His philosophical education was unconventional (going from engineering to working first-hand with one of the greatest philosophers of his day in Bertrand Russell) and he seems never to have felt the need to go back and make a thorough study of the history of philosophy. He was interested in Plato, admired Leibniz, but was most influenced by the work of Schopenhauer, Russell and Frege.

He was influenced by Leibniz's logical form. From The Problem of Logical form: Wittgenstein and Leibniz by Studia Philosophiae Christianae

The article is an attempt at explaining the category of logical form used by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Tractatus logico-philosophicus by using concepts from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s The Monadology.

He was influenced by Schopenhaur's division of reality into the phenomenal and the noumenal. From Schopenhauer's Influence on Wittgenstein by Bryan Magee.

Schopenhauer was the first and greatest philosophical influence on Wittgenstein, a fact attested to by those closest to him. He began by accepting Schopenhauer's division of total reality into phenomenal and noumenal, and offered a new analysis of the phenomenal in his first book, the Tractatus Logico‐Philosophicus.

IE, it is difficult to consciously break away from a tradition if one doesn't know much about the tradition in the first place. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatus1. Examples of names (the simple symbols for objects) are: "x,y,z,etc.

2. Examples of elementary propositions are functions such as: "'fx'', 'ϕ(x, y)', etc. — 013zen

4.24 - "Names are the simple symbols: I indicate them by single letters (x, y, z). I write elementary proposition as function of names, so that they have the form"'fx'', "ϕ(x, y)', etc."

I believe that he is not saying that the single letters x, y, z are objects, but is saying that these single letters indicate possible objects, such that the variable x indicates the objects ball, elephant or sandwich.

In order for an elementary propositions to picture the world, it needs two parts, representatives such as grass, green, tall, mountain, velocity and logical constants such as and, not, if, then, or.

Logical constants are not objects, they are rules that determine how the objects relate.

Consider the logical function F(x), where F(x) is true if the value x satisfies the function F. But as F and x are not only unknown, don't refer to anything and have no sense, F(x) cannot picture the world, and if cannot picture the world cannot be an elementary proposition.

Consider F(x) is true if x is green, The value x = grass satisfies the function, whilst the value x = strawberry doesn't satisfy the function. As F and x are now known, F being the object green and x being the objects grass and strawberry, the world can now be pictured, meaning that we now have an elementary proposition.

4.0312 - "My fundamental idea is that the logical constants are not representatives – that there can be no representatives of the logical facts"

Logic by itself, functions such as F(x), cannot fulfil the role of representatives, and as representatives are needed in addition to logic to picture the world, functions such as F(x) cannot be elementary propositions.

===============================================================================

We might be able to infer that an atomic fact, for something like this, might be something like: "v=d/t". I wonder. This could also explain why Witt lists: "time" as a "form of an object". — 013zen

A fact is a state of affairs in the world that obtains. A state of affairs is objects in possible combinations

Which is the state of affairs, d/t or distance divided by time? Which is the object, t or time?

From Russell's Introduction "In Wittgenstein’s theoretical logical language, names are only given to simples. We do not give two names to one thing, or one name to two things."

Therefore, the variable t cannot be the object, as being a variable it names more than one thing, and as Russell says, t cannot be a simple as it names more than one thing, and if not a simple cannot be an object.

2.0251 Space, time, colour (being coloured) are forms of objects.

From 2.051, time is the object, not the variable t.

Therefore, a state of affairs being objects in possible combinations cannot be d/t but must be time divided by distance. If this state of affairs obtains, then the fact is distance divided by time, not d/t.

(Kyle Banick – 1/3 – Necessity and contingency) -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThese limits of what is said versus what is shown are a question for me in how this work is presented as solving particular issues for the future. But I think it puts 'idealism versus realism' into the diagram rejected in 5.6331. — Paine

I wrote "Unfortunately, this line of enquiry cannot be developed within the Tractatus, as the Tractatus doesn't engage with ether Idealism or Realism."

Fundamentally, I am sure that the general opinion about the Tractatus is that Wittgenstein does not engage with Theories of Knowledge, such as Idealism and Realism. For Wittgenstein, the importance of philosophy was not about developing Theories of Knowledge but helping clarify one's own thought process.

7 - "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent"

IEP – Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889—1951)

Wittgenstein’s view of what philosophy is, or should be, changed little over his life. In the Tractatus he says at 4.111 that “philosophy is not one of the natural sciences,” and at 4.112 “Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts.” Philosophy is not descriptive but elucidatory. Its aim is to clear up muddle and confusion.

There is probably no Theory of Knowledge that hasn't been ascribed to Wittgenstein, and I am sure parts of the Tractatus can be read in support of one theory or another.

===============================================================================

I don't see how saying: "no part of our experience is at the same time a priori" could be an expression of idealism. — Paine

My basis understanding of the difference between Idealism and Realism is:

Idealism = the world exists in a mind. Berkeley said in the mind of God, the Solipsist says in the mind of the observer.

Realism = one world exists in the mind and another world exists outside the mind. The Indirect Realist says that these worlds are different. The Direct Realist says that these worlds are the same.

5.633 and 5.634 makes the point that we see a shape in the world, we don't see a representation of a shape in the world. But where is this world. Does this world only exist in a mind as Idealism proposes or does this world also exist outside the mind as Realism proposes. 5.633 and 5.634 says nothing about this .

===============================================================================

The single mention of "pure realism' probably comes from it being a thought experiment appended to saying: — Paine

5.62 "The world is my world: this is manifest in the fact that the limits of language (of that language of which I alone understand) mean the limits of my world

As before, he is not saying anything about where this world exists.

===============================================================================This difference between images built up through thoughts and words and what they show is evident throughout the book. — Paine

I thought the idea of the Tractatus Picture Theory is that there is no logical difference between an elementary proposition in language and a state of affairs in the world

A thought is what it shows. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusHe does engage with the issue: — Paine

5.634 and 5.641 could refer to either Idealism or Realism.

In 5.64, Wittgenstein says that solipsism coincides with pure realism. However, the term "pure realism" is only used once in the Tractatus.

How does Wittgenstein explain that solipsism coincides with pure realism? -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusAn elementary proposition in language is true if the state of affairs in the world it pictures obtains.

Elementary propositions

By elementary proposition, we naturally think of expressions such as "the apple is on the table ", "grass is red". "the Eiffel Tower is in London", "the house is next to the school". I would argue that words expressing concepts are indivisible and simples. I know that "house" may be described as "a roof over a wall over a foundation", but nevertheless, in a sense, all these words expressing concepts are simples, whether "house", "roof", "wall" or "foundation".

Kant's Unity of Apperception

2.0232 - “Roughly speaking: objects are colourless”

A name names a set of properties. A name is no more than a particular set of properties, in that if all the properties were removed from an object then there would be no object. An object doesn't "have" properties, an object "is" its properties.

Even though an object is no more than its set of properties, an object, when thought about as a concept, because of Kant's Unity of Apperception, has no properties. The unity of apperception transcends the parts in favour of the whole.

For example, as an analogy, when eating a New York Cheesecake, the enjoyment doesn't come from knowing anything about its individual ingredients, such as thinking that this flour tastes good, that I like the vanilla extract and the eggs are fresh. The enjoyment comes from the taste of the cheesecake as a unified whole, something that has transcended any particular combination of ingredients.

(Wittgenstein - Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Necessity and Contingency (Part 1/3) Kyle Banick)

States of affairs

A state of affairs is objects in combinations, where objects make up the substance of the world and are indivisible and simple.

As a Neutral Monist, I think that the substance that makes up the world are elementary particles, such as fermions and bosons, indivisible and simple. But Wittgenstein cannot be referring to fermions as objects, as a proposition such as "grass is green" is certainly not picturing fermions in combination.

However, Wittgenstein is talking about the world as a logical space containing logical objects. So how can grass be thought of as a logical object indivisible and simple?

Understanding Objects within Idealism and Realism

Suppose the Tractatus had been written from the viewpoint of Idealism. Then grass in the world in fact exists in the mind, and if exists in the mind, then must exist in the mind as a concept. As a concept, can be argued to be indivisible and simple, meaning that elementary propositions picturing a state of affairs becomes understandable from the perspective of Idealism.

Suppose the Tractatus had been written from the viewpoint of Realism, then how can grass be understood to be an object indivisible and simple?

On the one hand, the Direct Realist does believe that objects such as apples, tables, grass do exist in the world as objects indivisible and simple. They believe that when we perceive an apple in the world, there is truly an apple existing in the world, and would continue to exist even if there was no mind to observe it. This means that elementary propositions picturing a state of affairs becomes understandable from the perspective of Direct Realism.

On the other hand, the Indirect Realist does not believe that objects such as apples, tables, grass exist in the world as objects indivisible and simple, but only exist in the mind as concepts indivisible and simple. When we perceive an apple in the world, there is no apple existing in the world, but only in the mind of the observer. This means that elementary propositions picturing a state of affairs is not understandable from the perspective of Indirect Realism.

But the Tractatus avoids Idealism and Realism

2.02 - “The object is simple”

However, Wittgenstein in the Tractatus deliberately avoids any reference to Idealism or Realism. This leaves us with the problem of what exactly is the proposition "grass is red" picturing in the world, and how exactly can grass be thought of as an object in the world indivisible and simple?

In order to be indivisible and simple, grass cannot be a physical object in a physical world, but only can be a logical object in a logical world, and logical objects can be indivisible and simple.

If this is the case, and an elementary proposition in language is true if the state of affairs in the world that it pictures obtains, and the state of affairs in the world is not a physical world but a logical world, then language is not picturing a physical world but a logical world.

This supports either Idealism or Indirect Realism but not Direct Realism. Unfortunately, this line of enquiry cannot be developed within the Tractatus, as the Tractatus doesn't engage with ether Idealism or Realism. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusThe problem here is Wittgenstein's muddling of epistemological and metaphysical concepts without clear distinction or marking what is what. — schopenhauer1

There are many philosophical questions:

How does language and thought relate to the world?

How does language relate to thought?

Does the world we experience only exist in the mind, or does it also exist outside the mind, and if it does exist outside the mind, how does the world we experience in our mind relate to the world outside the mind?

Is Neutral Monism correct, that apples only exist as concepts in the mind and outside the mind are only elementary particles and elementary forces in space and time?

Do tables exist outside the mind?

Perhaps it doesn't matter, as you say:

The problem here is Wittgenstein's muddling of epistemological and metaphysical concepts

It just looks like axiomatic assertions without much explanation that one must either accept or not.

Are objects actual entities or are they simply functional as a role?

One is a "realism" whereby the world exists independently of facts, and the other is an idealism of sorts whereby the world is simply the logical coherence of the world.

Objects become denuded of any of its usual attributions, other than its function to support atomic facts.

Perhaps all that matters, as you say:

The ideas become anemic on their own (without the reader doing the heavy-lifting).

Perhaps the Tractatus is like a paper weight. As long as it does the job of keeping the papers from flying away it has done its job, in that as long as it has got people to think it has done its job. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusYour claim was that about his removal of relations and properties from his ontology. If ontology is about what exists, and properties and relations are shown, then even if they cannot be described they exist. — Fooloso4

Just because a picture can show a relation doesn't mean that the relation ontologically exists. A picture can show that the Empire States Building is 113m taller than the Eiffel Tower, but this does not mean that a difference in height of 113m ontologically exists in the world.

===============================================================================

He is not interested in the particular state of affairs that are modeled, but the possibility that is can be modeled. — Fooloso4

He is interested in possible elementary propositions, such as "grass is red", "grass is green", "grass is purple" and "grass is orange", showing possible states of affairs, such as grass is red, grass is green, grass is purple and grass is orange.

But this of necessity means that he is also interested in particular elementary propositions, such as "grass is purple", showing a particular state of affairs, such as grass is purple.

===============================================================================

It is the substance of the world not the facts in the world that prevents this: — Fooloso4

Yes, the world wouldn't exist without substance (ie, unalterable objects, simples) and there would be no propositions.

But on the other hand, as a proposition is not a single world, such as "grass", but words in combination, such as "grass is red", a proposition can only show in the world objects in combination (ie, states of affairs) such as grass is red. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusOne can perhaps understand Wittgenstein as a coherentist and not a correspondent theorist — schopenhauer1

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein was trying to avoid a pure Coherentism, where one proposition gets its meaning from another proposition etc, by ultimately founding propositions on states of affairs that exist in a world outside these propositions. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusHe doesn't. — Fooloso4

4.122 is saying that propositions cannot describe properties and relations, but can only show them. This is the difference between what is said and what is shown.

It is impossible, however, to assert by means of propositions that such internal properties and relations obtain: rather, this makes itself manifest in the propositions that represent the relevant states of affairs and are concerned with the relevant objects.

4.022 – A proposition shows its sense.

FH Bradley treats relations as objects, and if relations were objects, this would lead into an infinite regress problem. This is why Bradley concludes that relations don't ontologically exist.

Anscombe believes that relations are not objects, and therefore cannot be nameable. 3.1432 should be read that in aRb, it is not the case that a stands in relation to b, where R is an object, but rather that a stands in a certain relation to b.

However in a picture of a and b, as a relation is not an object, the relation between a and b cannot be shown.

For the Tracatus, relations are just objects coming together. This relation cannot be described in a proposition but can only be shown by the proposition itself. However, remembering to avoid any infinite regress by thinking that the proposition shows a relation by showing a relation by showing a relation, etc.

The Tractatus is not about universal concepts describing a world, but about particular propositions (which are particular thoughts) showing particular states of affairs.

===============================================================================

Every object in the world is composed of simple objects. These simple objects are in this sense universal. — Fooloso4

In the Tractatus, in the world are logical objects in logical configurations. These logical objects are simples, indivisible. There are many of them.

A Platonic Form is a universal of which each particular object is an instantiation.

The Tractatus is not a proponent of Platonic Forms, but treats each object as a particular, even if there are many of them. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusAnd yet, the meaning is often not understood. Your reading of Wittgenstein is a case in point. If we must infer what is meant then it is not evident from the outward form. — Fooloso4

Yes, that's the nature of language, where the meaning of a word often depends on context.

Where Wittgenstein writes in 4.002 "Language disguises thought", according to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, "disguise" can mean "to change the appearance of", "gives a false appearance to" and "obscures".

But as Wittgenstein points out, knowing what is the case also means knowing what is not the case.

So we know that "disguises" doesn't mean "jumps", "thinks", "stands", etc, etc.

Therefore we have some good idea as to the possible meanings of "Language disguises thought".

But as the Tractatus must be read as a whole, we can further narrow down its meaning by reading it in the context of the whole.

===============================================================================

Objects are particulars. A universal property of objects is to combine with other objects. — Fooloso4

However, one feature of the Tractatus is Wittgenstein's removal of relations and properties from his ontology. Another feature is his removal of universals in favour of particulars.

For the Tractatus, objects combine as particulars not as universals. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusFrom the outward form, how the thought is expressed, we do not see the logical form that underlies it. — Fooloso4

It is clearly the case that from the outward form of clothing we can infer the form of the body beneath it.

It is also clearly the case that from the outward form of language we can infer the form of the thought beneath it, otherwise language would be meaningless.

What use would language be if when someone said "please pass the sugar", no-one knew the thought behind these words.

From the outward form of language we clearly do know the form of thought beneath it.

Wittgenstein in the Tractatus does away with universals in favour of particulars, where the form of language maps directly not only with the form of thought but also with the form of states of affairs in the world.

===============================================================================

1.13 - The facts in logical space are the world — Fooloso4

The world is a logical space.

In this logical space are possible states of affairs.

A state of affairs consists of logical objects in logical configurations

If a state of affairs obtains, then it is a fact -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusHere Wittgenstein draws an analogy between "clothes" and "a body" with "language" being the clothing and "thought" being the body that is clothed. So, there is a distinction that is made between the two — 013zen

4.002 may be correct that language disguises thought, but is not inconsistent with the idea that language is thought.

I see a one-storey brick building, think one-storey brick building and say "house". I see a two-storey stone building, think a two-storey stone building and say "house".

It is true that the word "house" has disguised the thoughts, but this does not detract from the fact that the word "house" is the thought of a one-storey brick building and the word "house" is also the thought of a two-storey stone building.

===============================================================================

These are examples of propositions, not elementary propositions, though. — 013zen

As I understand it, for the Tractatus:

The world is a logical space in which can only exist logical objects in logical configurations.

A state of affairs is a logical configuration of logical objects. A state of affairs may or may not obtain. If it obtains then it is a fact. For example, grass is green and grass is red are possible states of affairs. Grass is green obtains and grass is red doesn't obtain.

All states of affairs are independent of each other, in that either grass is green or grass is red. It cannot be the case that grass is both green and red at the same time.

An elementary proposition stands for a state of affairs

A name stands for an object.

Therefore an elementary proposition will be an arrangement of names.

An elementary proposition will be true if the state of affairs obtains.

For example, the elementary proposition "grass is green" is true if the state of affairs grass is green obtains.

All elementary propositions are independent of each other, in that either "grass is green" or "grass is red". It cannot be the case that "grass is both red and green at the same time".

That an elementary proposition is conceivable does not mean that it is true, for example "grass is red". In the same way, because a state of affairs is possible it doesn't mean that it obtains, for example grass is red.

For Wittgenstein, propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions, for example,

"grass is green and the sky is blue"

(The Theory of elementary propositions, Jeff Speaks, Phil 43904, 8 Nov 2007) -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusWittgenstein's objects are "simples"

Tractatus 2.02 Objects are simple.

From Wikipedia - Simple (Philosophy)

In contemporary mereology, a simple is any thing that has no proper parts. Sometimes the term "atom" is used, although in recent years the term "simple" has become the standard.

From Jeff Speaks Wittgenstein on facts and objects: the metaphysics of the Tractatus

What does it mean to say that an object is simple? One thing Wittgenstein seems to mean is that it cannot be analyzed as a complex of other objects. This seems to indicate that if objects are simple, they cannot have any parts; for, if they did, they would be analyzable as a complex of those parts. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusA proposition in some sense contains a thought, but a thought is not identical with a proposition............................Wittgenstein says it is becoming clear to him why he thought that thinking and language were the same. He didn't say that its become clear that they are the same — 013zen

I don't believe that an isomorphism necessarily suggests a certain independence between each structure, but in practice I admit it is used to talk about independent structures. — 013zen

It all depends on whether, in the Tractatus, for Wittgenstein, language and thought are the same thing.

If not, then isomorphism may be the suitable world. If they are, then as an object such as an apple cannot be isomorphic with itself, isomorphism may not be the suitable word.

A starting position to determine whether in the Tractatus language and thought are the same thing could be the article The Thought (Gedanke): the Early Wittgenstein, written by Sushobhona Pal

His conclusion is " Apart from this, apparently, the Tractatus implies that the realms of thought and language coincide", or as he says elsewhere " are "coextensive".

As he writes:

Wittgenstein writes in unequivocal terms that we cannot think what we cannot think and therefore what we cannot think we cannot say either. It means what cannot be thought cannot possibly be spoken about either. These entries suggest that thinking and language (speaking) are coextensive.

For Wittgenstein, if a thought is a picture of the world and a proposition is a picture of the world, then how can a thought not be a proposition?

===============================================================================

First of all...why did you say grass is red and not green? xD Secondly, I don't take "Grass is red" or "Grass is green" or anything of the sort to be representative of an elementary proposition for Witt. These are examples of propositions. — 013zen

In Wittgenstein's terms (as I understand it), grass is red, grass is green, not grass is red and not grass is green are States of Affairs.

The elementary propositions "grass is red" "grass is green" "not grass is red" and "not grass is green" may be true or false

If the elementary proposition "grass is green" is true, then grass is green is a fact. Alternatively, if grass is green is a fact, then the elementary proposition "grass is green" is true. -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's TractatusLeaving aside the perhaps trivial point that we can have thoughts that are non-propositional...I don't read him as suggesting that language is the only picture-making tool at our disposal. — J

Wittgenstein wrote before the Tractatus that he thought that thinking and language were the same.

Notebooks 1914-16 – 12/6/2016 – page 82.

Now it is becoming clear why I thought that thinking and language were the same. For thinking is a kind of language. For a thought too is, of course, a logical picture of the proposition, and therefore it just is a kind of proposition.

1.1 – The World is the totality of facts, not of things

3 – A logical picture of facts is a thought

Therefore, a thought is a picture of facts in the world

4 – A thought is a proposition with a sense

4.022 – A proposition shows its sense.

Therefore, a proposition is a thought

5.6 – The limits of my language mean the limits of my world

Therefore, my thoughts about the world are limited by the propositions I use in language.

It seems that Wittgenstein doesn't distinguish between propositional thoughts, "snakes are reptiles" and non-propositional thoughts, "Indiana Jones fears snakes"

As Bertrand Russell writes in the Introduction to the Tractatus:

It is clear that, when a person believes a proposition, the person, considered as a metaphysical subject, does not have to be assumed in order to explain what is happening. What has to be explained is the relation between the set of words which is the proposition considered as a fact on its own account, and the “objective” fact which makes the proposition true or false.

If thinking is a kind of language, then thinking IS language rather than thinking being isomorphic to language, because for Wittgenstein, thinking and language are not two separate isomorphic objects but rather two aspects of the same object (Wikipedia - Isomorphism). -

Trying to clarify objects in Wittgenstein's Tractatusthe Tractatus presents a three part isomorphism between: 1. Thoughts 2. Language 3. Reality — 013zen

I'm not sure that isomorphism is the right word, as it suggests that they are independent of each other.

Thought and language are two aspects of the same thing. A proposition is a thought and a thought is a proposition. As Wittgenstein says, the limits of my language is the limits of my world. The world is the content of my thoughts (ie, of my propositions)

Wittgenstein is careful to avoid giving his opinion as to where this world exists, inside the mind or outside the mind.

It is more the case that thought IS language rather than thought maps to language, and the world IS the content of thought (and language) rather than maps to thought (and language).

===============================================================================

A proposition can be analyzed into an elementary proposition, and to this corresponds an atomic fact. — 013zen

You need to introduce "state of affairs" earlier on.

IE, the elementary proposition (aka atomic proposition) "grass is red" corresponds (not in the sense of represents but more in the sense of displays) with the state of affairs grass is red, but doesn't correspond with the atomic fact grass is red, as the state of affairs grass is red doesn't obtain in the world.

The Tractatus only deals with concrete objects, such as grass and apples, and concrete properties, such as yellow and red. The Tractatus doesn't deal with abstract things, such as beauty and love, and abstract properties, such as yellowness or redness. This is why the Tractatus is so limited, in the sense that Philosophical Investigations isn't.

Within the Tractatus, objects are treated as logical objects, unalterable and indivisible, not physical objects.

Not all objects can exist in the world. The world consists of a logical space. This logical space is the set of all possible states of affairs. Only those objects having a suitable logical form can exist in this logical space. If a possible state of affairs obtains then this is a fact.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum