-

Is indirect realism self undermining?This resource offers what I am talking about (or close enough).

Direct realism, also known as naïve realism or common sense realism, is a theory of perception that claims that the senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world. In contrast to this direct awareness, indirect realism and representationalism claim that we are directly aware only of internal representations of the external world.

...

Direct realists might claim that indirect realists are confused about conventional idioms that may refer to perception. Perception exemplifies unmediated contact with the external world; examples of indirect perception might be seeing a photograph, or hearing a recorded voice. Against representationalists, direct realists often argue that the complex neurophysical processes by which we perceive objects do not entail indirect perception. These processes merely establish the complex route by which direct awareness of the world arrives. The inference from such a route to indirectness may be an instance of the genetic fallacy. — plaque flag

We both agree with your resource laying out Direct and Indirect Realism. But you must admit it makes no reference to language, linguistics or language games in distinguishing Indirect from Direct Realism.

The direct realist tries to do without this internal image, but not without sense organs. The direct realist is not so much focused on how the eyes see the tree and not the image of the tree, even if they will put the event this way. What really matters are linguistic norms. The 'I' that sees the tree exists within the space of reasons. The 'I' is like a character on a stage among others egos. Direct realists aren't worried about the internal structure of this 'I.' That's not the point. Language is fundamentally social, world-directed, and self-transcending. To see the tree is more usefully understand as to claim 'I see a tree.' We now think of this claim as a move in a social game. — plaque flag

So why keep introducing references to language, linguistics and language games.

Why say that what really matters are linguistic norms, when linguistic norms are not part of what distinguishes Indirect from Direct Realism, according to your resource. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?It would make sense that the brain evolved to make us believe we are directly interacting with the world even if it is really a virtual world — lorenzo sleakes

:up: -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I suggest dropping that terminology. External to what ? — plaque flag

This resource offers what I am talking about (or close enough). — plaque flag

The term "external" comes from the resource you recommended.

Direct realism, also known as naïve realism or common sense realism, is a theory of perception that claims that the senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?No, I was switching between provisionally explaining the argument that perception is linguistic as if it were true, and expressing doubts about it. This should be obvious. — Jamal

Though you cannot doubt that perception is linguistic, as previously you wrote "It's a deeper point than that, to do with the fact that in situations of perceiving we are always already linguistic, because of what we are." -

Is indirect realism self undermining?There's just the world, our world, the one we talk about. — plaque flag

Yes, this relates back to the Kant passage, but it doesn't address the question as to whether we have indirect or direct knowledge of this world.

The point is that concepts are public norms. The concept pain doesn't get its meaning from private experience. — plaque flag

If the concept pain doesn't get its meaning from private experience, I stub my toe and feel pain, where does it get its meaning from ?

The self is not 'behind' the senses or its data. The self is (I claim) a discursive performance of the body, a creative appropriation of community norms. — plaque flag

I don't think that "the self" is normally defined as part an individual and part the community in which they live.

Respectfully, I claim that you don't yet understand the position. 'Mind-independent world' is potentially nonsensical, almost definitely misleading. 'Private experiences' too. — plaque flag

You quote: Direct realism, also known as naïve realism or common sense realism, is a theory of perception that claims that the senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world.

Isn't an external world a mind-independent world ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?RussellA perceives direct realists only indirectly: the direct realist in his head does not resemble the direct realist as it is in the external world — Jamal

It seems you are redefining Direct Realism to include linguistics in a way not generally used in the literature, for example, SEP The Problem of Perception.

Closest I can come is to imagine how perception works when we're wrapped up in a physical activity, like running to catch a ball or playing an instrument (or hammering of course). These don't seem very linguistic to me, though I could well be wrong. I'm not committed to perception-as-essentially-linguistic — Jamal

It's a deeper point than that, to do with the fact that in situations of perceiving we are always already linguistic, because of what we are. — Jamal

You say that on the one hand you're not committed to perception as essentially linguistic but on the other hand you say that perception is linguistic.

Regardless, Direct Realism is the position that private experiences are direct presentations of objects existing in a mind-independent world, not about the nature of language. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?We can talk about the world and just be wrong sometimes. — plaque flag

Which world are you referring to, the world as we perceive it, or the world as it is independent of our perception of it.

These 'private experiences' are tooth fairies. The 'mindindependent world' is Candyland. — plaque flag

Are you saying you have no private experiences, you stub your toe and feel no pain ?

Are you saying the Universe didn't exist for the 13.8 billion years before humans appeared on Earth, 315,000 years ago ?

I think Kant gets something right. — plaque flag

I agree with the Kant passage about cognition, in that the mind needs information from the other side of our senses, but this doesn't address the question as to whether this information is indirect or direct. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?We perceive pain and we perceive a tree.

The Direct Realist says that our private perception of a tree is a direct presentation of something existing in a mind-independent world.

Wouldn't it follow, if Direct Realism is true, that our private perception of pain is also a direct presentation of something existing in a mind-independent world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Presumably an indirect realist is not just mumbling about their internal illusion but trying to share news about the 'real' world (or whatever an indirect realist wants to call the one we live in together). — plaque flag

It is curious that language, a representational system, where words are symbols, is being used as an explanation of Direct Realism, an explicitly non-representational system.

Language is needed to talk about Direct Realism, but language should not be confused with Direct Realism. Language is antithetical to Direct Realism. Although language may be used to understand the planet Venus, this does not mean that the planet Venus is a feature of language. Similarly, as language may be used to understand Direct Realism, this does not mean that Direct Realism is a feature of language.

I can directly feel pain and I can directly see a tree independently of any private or public language . There are many things I see that I don't know the word for. Private experiences don't depend for their existence on language.

What is Direct Realism. It isn't about language. From the SEP article on The Problem of Perception para 3.4.1 Naive Realism in Outline one reads:

1) Consider the veridical experiences involved in cases where you genuinely perceive objects as they actually are. At Level 1, naive realists hold that such experiences are, at least in part, direct presentations of ordinary objects. At Level 2, the naive realist holds that things appear a certain way to you because you are directly presented with aspects of the world, and – in the case we are focusing on – things appear white to you, because you are directly presented with some white snow. The character of your experience is explained by an actual instance of whiteness manifesting itself in experience.

2) For the naive realist, insofar as experience and experiential character is constituted by a direct perceptual relation to aspects of the world, it is not constituted by the representation of such aspects of the world. This is why many naive realists describe the relation at the heart of their view as a non-representational relation.

Direct Realism is the position that private experiences are direct presentations of objects existing in a mind-independent world, not that within social communities there are language games. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The social group is part of the world not external to it. — Richard B

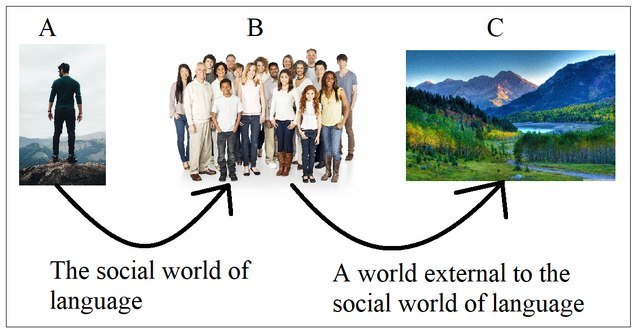

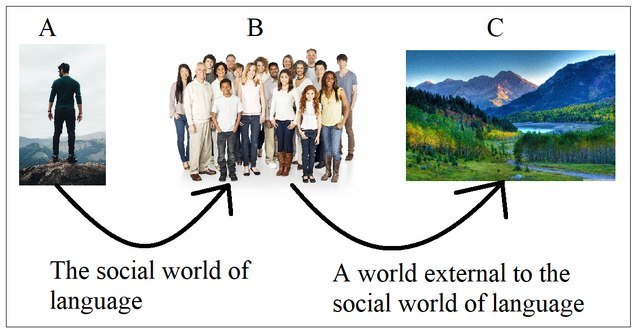

It depends which "world" you are referring to. Sometimes philosophers talk about the "world" without specifying exactly where they think it is. For example, Wittgenstein in Tractatus writes in para 1 "The world is everything that is the case.", yet never explains where he thinks this world is.

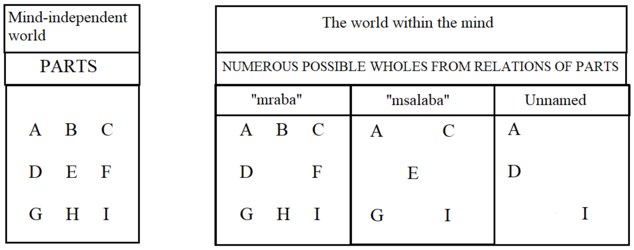

There are different "worlds". There is the world within my mind, there is the world in the collective minds of a social group sharing a common language, there is the world external to any mind and there is the world that is the sum of all of these. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?It's all around us. It's the world. It's the one philosophers talk about and make claims about.......................We have to be talking rationally in a shared language about a shared world. — plaque flag

Your posts are about the relationship between the individual and a social world of which they are a part, of which language is critical.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree about the importance of language.

The problem is, however, the relationship between the social group and the world external to the social group, and whether the social group have indirect or direct knowledge of this external world.

The Direct Realist would say that the tree exists in a mind-independent world exactly as we perceive the tree to be in our minds. The Indirect Realist would disagree. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?This assumption of the instrument/medium is what's being mocked as a fear of truth that confuses itself for a fear of error.

With suchlike useless ideas and expressions about knowledge, as an instrument to take hold of the Absolute, or as a medium through which we have a glimpse of truth, and so on ..., we need not concern ourselves. — plaque flag

Considering that we only get our knowledge about the external world through our senses, it seems very cavalier for Hegel to write that we need not concern ourselves about the role our senses play in understanding the external world.

But what he presents is no discovery. — plaque flag

I agree. As an Indirect Realist I agree with Searle that the experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain.

Unfortunately, many who argue against Indirect Realism don't accept this. They believe that Indirect Realism requires that there must be something in the brain that is interpreting incoming data, something they often call a homunculus.

We talk about the world (directly) in our language according to our rational and semantic norms...A philosopher (in that role) can't deny it. He'd be talking about our world or just babbling. — plaque flag

I agree that we rationally and directly talk about the world.

The question is, where is this "world". Wittgenstein, for example, in Tractatus avoided this question.

The Indirect Realist would agree that this "world" exists in language. But this doesn't distinguish the Indirect Realist from the Direct Realist.

What else distinguishes the Direct Realist from the Indirect Realist ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Here's Hegel.

For if knowledge is the instrument by which to get possession of absolute Reality, the suggestion immediately occurs that the application of an instrument to anything does not leave it as it is for itself, but rather entails in the process, and has in view, a moulding and alteration of it.

Or, again, if knowledge is not an instrument which we actively employ, but a kind of passive medium through which the light of the truth reaches us, then here, too, we do not receive it as it is in itself, but as it is through and in this medium. — plaque flag

Hegel sets out the Indirect Realist's problem with bridging the gap between our conscious mind on the one side and a mind-independent world on the other, between knowledge and the Absolute.

Whether knowledge is an instrument or passive medium to bridge the gap, it alters what passes from a mind-independent world to our conscious mind, meaning that our perceptions are indirect.. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Perhaps you can find those that call themselves 'direct realists' that do this, but to me this is the wrong way to go and misses what's good in 'my' take on direct realism. — plaque flag

What's your take on Direct Realism ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?There is debate among modern interpreters over whether Kant is an indirect realist — Jamal

Philosophers have made good livings from arguing as to what Kant meant. Early twentieth-century philosophers of perception presented their direct realist views of perceptual experience in anti-Kantian terms. Today, some philosophers attempt to place Direct Realism within a Kantian framework by arguing that Kant can be read as a conceptualist rather than non-conceptualist.

Perhaps the debate comes down to the two varieties of Direct Realism, the early 20th C Phenomenological Direct Realism and the contemporary Semantic Direct Realism. Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) may be described as a direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world. Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) may be described as an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world.

He explicitly states that we perceive the external world "immediately," and what he calls representations constitute the perception and determination of objects, rather than standing in for them as images or constructions. We have awareness of objects not through anything like an inference from or construction of an internal image, but through an act of synthesis that puts the objects directly before us. — Jamal

Both the Indirect Realist and Direct Realist would agree that we perceive the world "immediately".

As Searle wrote: The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

As an Indirect Realist, I feel pain, I don't feel the representation of pain. Similarly, when I see a tree, I directly see the tree, I don't see the representation of a tree.

The Indirect Realist differs to the Direct Realist. The Indirect Realist argues that the tree I see exists only this side of the senses, whereas the Direct Realist would argue that there is also an identical tree the other side of my senses.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist perceive the world "immediately", though they differ as to where exactly this world is.

And yes, he does use "realism" to refer to claims that we can know things in themselves — Jamal

I assume we both agree that Kant was not an Berkelean Idealist, where physical objects are constructions of the mind. Kant's transcendental idealism may be described as, on the one hand as a rejection of Berkelean idealism, and on the other hand that the things we perceive exist independently of us and about which we cannot directly cognize, yet grounds the way they appear to us.

In other words, for Kant, "Existence", in that there are things-in-themselves, "Humility", in that we know nothing of things-in-themselves and "Affectation", in that things -in-themselves causally affect us.

For Kant, the noumenal realm is not reality, since it is merely a product of reason. Rather, reality is that which we know about through experience and science. The clue to this is that reality for Kant is one of the categories of the understanding, thus it can only apply to phenomena. — Jamal

You are making the case for Indirect Realism.

For the Direct Realist, perceptual reality is the noumenal world, the other side of our senses, where there are things in a world outside our mind that are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

For the Indirect Realist, perceptual reality is the phenomenal world, this side of our senses, where things outside our mind are perceived indirectly and inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

In summary, for both Kant and the Indirect Realist, perceptual reality is the phenomenal world this side of the senses whereas for the Direct Realist perceptual reality is the noumenal world , the other side of our senses. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I don't even know if minds exist. — Moliere

It would be difficult to have thoughts without a mind. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?That one's easy -- pain is tied to the world — Moliere

The same question. If both pain and the colour red are tied to the world, how does the Direct Realist know that the object of one perception, eg pain, doesn't exist outside the mind, but the object of another perception, eg red, does exist outside the mind.

I would say "There is a real world" -- "out there" in particular is troublesome. Out where? — Moliere

According to Realism, there is a real world out there that exists independently of the mind's perception of it. According to Idealism, there isn't a real world out there that exists independently of the mind's perception of it.

If we directly perceive entities, but we do not directly perceive causal chains, then this is still a form of direct realism. — Moliere

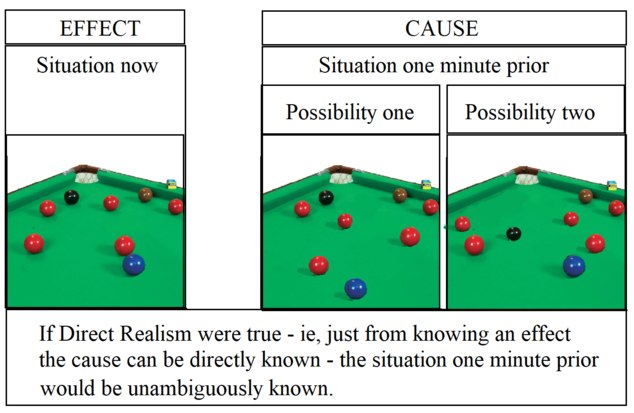

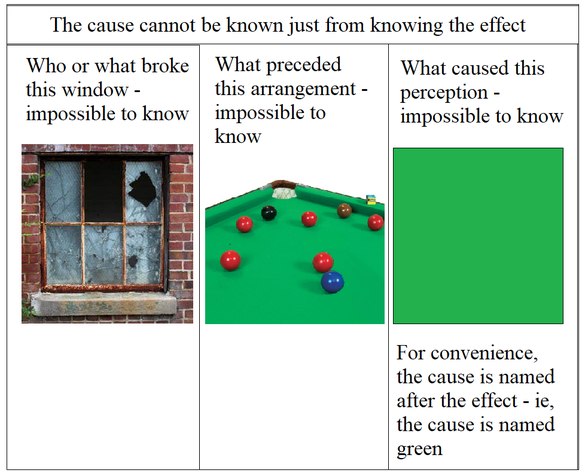

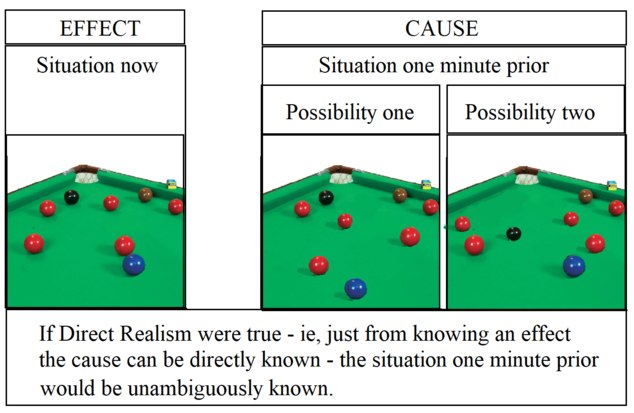

Neither the Indirect nor Direct Realist when perceiving a red post-box, just from the perception itself, are able to perceive the causal chain going backwards in time. The Indirect Realist accepts this, the Direct Realist doesn't.

That's where I was going with my notion of the surface: so there is a case rather than the positions in abstract. — Moliere

In a sense, we can only see the surface, we can only see the red post-box, We cannot directly see the substratum beneath the surface, the thing outside our mind, the other side of our senses, the thing that caused us to see a red post-box. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Is it really so strange ? Philosophy can even be framed as a series of creative misreadings or violent appropriations of influences. — plaque flag

True, I used the writings of Searle, a Direct Realist, against Direct Realism.

So Hegel fixed Kant and offered a sophisticated kind of direct realism — plaque flag

Hegel's Absolute Idealism is not at odds with Indirect Realism.

Abandon all hope ye who enter here take private mental images seriously — plaque flag

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist believe in the private mental image, in that in the mind we have private experiences, such as pain, that are impossible to explain to others. The Indirect Realist is not someone who needs to believe in Wittgenstein's private language or solipsism, but does believe that they are part of a social world within which they are able to communicate using a public language.

What distinguishes the Indirect and Direct Realist is the location of this "world". Both the Indirect and Direct Realist agree that at the least this "world" exists in the mind. The disagreement is whether an identical "world" exists outside the mind.

There is no need to decide that color is unreal because it is correlated with wavelengths, etc. — plaque flag

The colour red is real in our mind and the wavelength is real outside our mind.

We agree that the colour red this side of our senses is correlated with a wavelength the other side of our senses.

The Indirect Realist believes that the colour red and the wavelength are different. How does the Direct Realist justify that two things which are commonly accepted as being different are in fact the same. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I might be more in the direct realist camp, so I'll try to answer this — plaque flag

As an Indirect Realist, I agree with everything you wrote in your post. It is interesting that you used Kant, in today's terms an Indirect Realist, to support your case.

Kant discussed "Existence", in that there are things-in-themselves, "Humility", in that we know nothing of things-in-themselves and "Affectation", in that things -in-themselves causally affect us. Kant's concept of a thing-in-itself is not that of a Direct Realist.

We need not assume in the first place that we are trapped behind a wall of sensations. This methodological solipsism is unjustified, in my view. Concepts are public. They exists within a system of norms for their application. This is why bots can talk sensibly about pain and color. — plaque flag

Wittgenstein's beetle in the box analogy in para 293 of Philosophical Investigations may be used as an argument against Direct Realism. The Direct Realist would argue that if two people are looking at the same object in the world, as both will be perceiving the same object in the world immediately and directly, their private mental images must be the same, meaning that each will know the others private sensations. However, this wouldn't agree with Wittgenstein's para 272 that each of us has private experiences not known by others.

Wittgenstein's beetle in the box analogy also explains how a public language is possible, even though our private experiences are unknown to others. In a public language, our private experiences, as with the beetle, drop out of consideration.

I assume that both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree:

1) All our information about things external to our senses comes through our senses.

2) We directly perceive things this side of our senses, such as apples, trees, mountains, etc.

3) Science tells us that the properties of things the other side of our senses, such as wavelength, are different to the properties this side of our senses, such as the electrical signal that travels up the optic nerve to the brain.

4) Even though we each have private experiences, we can talk about these private experiences using a public language, allowing us to live in social communities.

The Indirect Realist would argue that the world outside our senses is different to the world we perceive this side of our senses. The Direct Realist would argue that not only is the world outside our senses the same as the world we perceive this side of our senses but also that we directly know the world outside our senses.

The question for the Direct Realist is how is it possible to know that the world outside our senses is the same as the world we perceive this side of our senses, when science tells us that what is on the other side of our senses is different to what is this side of our senses. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The Direct Realist agrees that pain doesn't exist external to the senses of any perceiver, but argues that the colour red does.

How does the Direct Realist explain, given that all their knowledge of the world external to their senses comes through their senses, how the perceiver knows that one perception is not direct, eg, pain, but another perception is direct, eg, the colour red ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Why would there be properties? Aren't these just predicates? — Moliere

Predicates are distinct from properties. Predicates are linguistic whilst properties are extralinguistic. Predicates are tied to particular languages, in that schwarz is tied to German as black is tied to English, but the property black is tied to neither. There is a real world out there and the things in it have properties whether or not there are any languages or language-users.

To my understanding, there are two types of Direct Realism, Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) and Semantic Direct Realism (SDR). PDR is an direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world. SDR is an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world. As PDR is extralinguistic and SDR is linguistic, properties exist in PDR whilst predicates exist in SDR.

I can perceive that an apple has the property of greenness even if I don't know the name of that particular shade of green, but I need the predicates within language in order to say that "the apple is green".

in relation to causation no direct realist would say "we can see causal chains all the way back" because we are situated in time — Moliere

But that is exactly what the Direct Realists is saying. The Direct Realist is saying that they directly know the apple, not just how the apple seems, even though there is a causal chain through time from the apple to our perception of the apple.

The Direct Realist holds a contradictory position. First, that they cannot see through causal chains backwards through time and second that they can directly see the prior cause of a perception.

Rather than saying a direct realist would hold that we see reality as it is, that the substrate is real and we directly perceive it, I'd say that the direct realist states that there's nothing indirect. — Moliere

In the absence of a Direct Realist arguing their case, I would have thought that your representation is the opposite of what a Direct Realist believes, in that it is surely the case that the Direct Realist believes that "we see reality as it is, that the substrate is real and we directly perceive it". -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Well -- maybe we need new terms then. — Moliere

Perhaps the term "Direct Realism" should be thought of as a name rather than a description, in the same way that "Transcendental Idealism" is neither transcendental nor idealism.

Other names that incorrectly appear to be descriptions are: Red Panda, white chocolate, titmouse, gravy train, buffalo wing, cat burglar, butterfly, coat of arms, lady bug, Asian flu, Chinese checkers, Arabic numerals, the Fibonacci sequence, the Pythagorean theorem , koala bears, king crabs, glow-worms, fireflies, horned toad, slow worms, starfish, jellyfish, velvet ants, strawberries, peanuts, Panama hats, English horns, Jerusalem artichokes, Bombay duck, The Isle of Dogs, catgut and funny bone.

I could then say that yesterday I was thinking about the meaning of Direct Realism whilst eating several spicy buffalo wings. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?In TPF discussions I'll stick with anti-realist Direct Realist -- it seems to fit, given what's been said. — Moliere

That's like saying you are an Atheist Christian, or a vegan carnivore.

One thing that cause and effect naturally invokes is time.............Then you have to have a theory of cause and effect which is usually to say they are events, and effects are those which come after causes. But what is an event? — Moliere

The Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that perception is a direct awareness of properties existing in the mind, such as the direct perception of the colour red.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that it is only through our senses that we know the external world.

Science tells us that the object in the external world causing our perception of the colour red has a wavelength of 700nm.

The Indirect Realist argues that the properties existing in our mind, the colour red, are different to the properties of the object in the external world that caused them, a wavelength of 700nm

The Direct Realist argues that the properties existing in our mind, the colour red, are the same as the properties of the object in the external world that caused them, the colour red.

In effect, the Direct Realist is arguing that the properties of an effect at a later time are the same as the properties of its cause at an earlier time.

The Direct Realist is arguing that the properties of an effect are the same as the properties of its cause

But we know this is not the case, When getting a headache from looking at a bright light, we know that bright lights are not in themselves headaches. When glass breaks from being hit by a stone, we know that stones in themselves are not breaking glass. When enjoying reading a book, we know that books in themselves are not enjoyment.

The Direct Realist's position that the properties of an effect are the same as the properties of its cause cannot be justified. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?It's not just the philosophers who generate a multitude of theories of causation — Moliere

Is it any more complicated that for every effect there is a cause.

I wouldn't say I know that, but it's interesting to attribute minds to bacteria. Would they have the concept of causality? — Moliere

They might well have. The New Scientist article Why microbes are smarter than you thought discusses communication, decision-making, city living, accelerated mutation, navigation, learning and memory.

evolution doesn't have a point, does it? — Moliere

Not in a teleological sense. Sean Carroll in his lecture The Big Picture: From the Big Bang to the Meaning of Life touches on evolution and causality. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Indirect Realism holds that perception is a direct awareness of objects and events existing in the mind, and an indirect awareness of objects and events existing in a mind-independent world.

Direct Realism holds that perception is a direct awareness of objects and events existing in the mind, and a direct awareness of objects and events existing in a mind-independent world.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that it is only through our senses that we know the mind-independent world.

The Direct Realist would need to explain the circular problem as to how on the one hand we can have direct knowledge of things as they exist independently of our sensations about them in a mind-independent world yet on the other hand we cannot have knowledge of these things independently of our senses. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The story from evolution to concept isn't understood — Moliere

Though we do know that after 3.5 billion years of life's evolution, the concepts in the human mind are more complex that the concepts in the mind of the earliest bacteria.

My scenario pointed out that the philosophers have come up with at least three distinct theories of cause, rather than a total absence of the notion of cause -- giving me reason to doubt that cause is innate (else wouldn't they have come up with the same theories?). — Moliere

Ten philosophers expert in the same field will have ten different theories. As Searle said:

"I realize that the great geniuses of our tradition were vastly better philosophers than any of us alive and that they created the framework within which we work. But it seems to me they made horrendous mistakes."

I'd say the reason people learn this notion so often has more to do with our environment than it does with ourselves. — Moliere

Then what has been the point of 3.5 billion years of evolution if an instinctive feel for causality is not part of the structure of the human brain. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I think "causation" is one of those habits which we learn from those around us who teach us how to use it. It's different from what we feel, i.e. red or pain...So it's more likely that we're inventing causation than it's innate, given the evidence of the intelligent and creative. — Moliere

If causation was not innate and was something learned, as with all things, some people would learn it and some wouldn't.

Imagine someone who hadn't leaned about causation, who were oblivious to the concept of cause and effect. Would they be able to survive in a world where things happen, where future situations are determined by past events. Suppose there was someone who treated the law of causation as optional, who turned a blind eye to the fact that present acts have future consequences. Why would they eat, why would they drink, why would they move out of the path of a speeding truck, why would they study, why would they do anything, why wouldn't they just curl up in a corner of the room.

I would suggest that such people would quickly die out, to be inevitably replaced by those well aware that present acts do have future consequences.

After life's 3.5 billion years of evolution in synergy with the unforgiving harshness of the world it has been born into, something as important to survival as knowing that present acts do lead to future consequences will become built into the genetic structure of the brain, meaning that within the aeons of time life has survived on a harsh planet, knowledge that present acts do lead to future consequences will become an instinctive part of human nature.

As with other features of the human animal, an instinctive feel for causation will be no different to other things we feel, such as pain and the colour red. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?However, I think I'd call myself a realist, rightly, yet deny there even is a sub-stratum. — Moliere

Realism is defined as the assertion of the existence of a reality independently of our thoughts or beliefs about it, so a Realist wouldn't deny that there is a sub-stratum.

I wouldn't reduce reality to either phenomenology or semantics (or science) — Moliere

The Phenomenological Direct Realist believes they directly perceive something existing in a mind-independent world even if they don't know its name. The Semantic Direct Realist believes they directly perceive an apple existing in a mind-independent world.

For the Direct Realist, the terms phenomenology and semantics distinguish important features of their view of reality.

That's because without access to the substrate there's no way to check our inferences, or a way to check if there is a relationship between the substrate and the surface. We could only check it against the surface. It may match the substrate, but we'd never know due to its indirectness. — Moliere

That's true, but I have an innate belief in the law of causation, in that I know that the things I perceive in my mind through my senses have been caused by things existing outside my mind in a mind-independent world.

My belief in the law of causation is not based on reason, but has been been built into the structure of my brain through 3.5 billion years of life's evolution within the world.

I have no choice in not believing in the law of causation as I have in not believing I feel pain or see the colour red. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Effect: private sense data that cannot be publicly verified as either true or false. — Richard B

I think everyone would agree with this, apart from perhaps a psychic empath.

Cause: an unknowable something that is out of reach because all we know for certain is our private sense data. — Richard B

Very true.

-

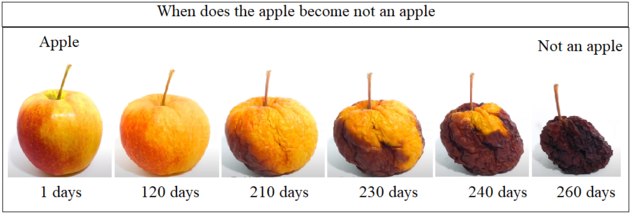

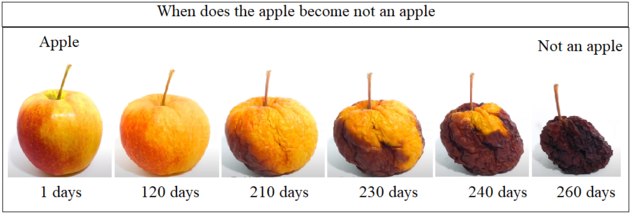

Is indirect realism self undermining?They are no longer apples the moment we stop calling them apples — Moliere

As an Indirect Realist, my belief is that as apples exist in the mind, exist in perception, cognition and language and not in a mind-independent world. As you say, they can therefore be brought into existence and removed from existence just by the power of thought.

But the indirect realist wants to assert, all we have is perception, and there's something real out there underneath it all as an inference, as I understand it in this thread, starting from naive realism -- that what we see is what's the case, modified to our perception. — Moliere

I agree that there is the surface of perception, cognition and language which is real and we have direct access to, and there is a substratum which is also real. The Indirect Realist believes that they can only make inferences about what exists in this substratum, whilst the Direct Realist believes they can directly perceive what exists in this substratum.

But if so I think it has to be established by some other means than by looking at change, — Moliere

There are different approaches to Direct Realism. Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) is an direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world. Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) is an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world.

As language is one aspect of cognition, the change in object from apple to non-apple is more relevant to SDR than PDR. As you say " They are no longer apples the moment we stop calling them apples".

However, I agree that change is not as relevant to PDR as it is to SDR. The following is more relevant to PDR.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist agree that the substratum is real and exists. They both perceive, cognize and talk about "apples". The Direct Realist believes that apples exist in a mind-independent world, the Indirect Realist doesn't.

I can perceive things that I don't have words for. For example, exotic fruits of Asia. Therefore, it's possible to be able to perceive an apple without knowing that it has been named "apple".

As both the Indirect and Direct Realist agree they perceive change, we cannot use change to determine who is correct. Therefore, just consider the picture at 230 days. As both the Indirect and Direct Realist are able to perceive things they have no name for, remove any reference to the name" apple". The Direct Realist would argue that the object at day 230 exists as it is seen in a mind-independent world, whilst the Indirect Realist would argue that it doesn't.

The thing perceived at 230 days is part ochre at the top and part umber at the bottom, contained within a circle and supporting a short vertical line above. Reducing, we have a straight line, a circle, some colour and relationships between them.

The Indirect Realist would propose that these features exist only the mind. The Direct Realist would propose that these exist not only in the mind but also in a mind-independent world. Both the Indirect and Direct Realist agree that these features exist in the mind, however the Direct Realist also proposes in addition that these features also exist in a mind-independent world.

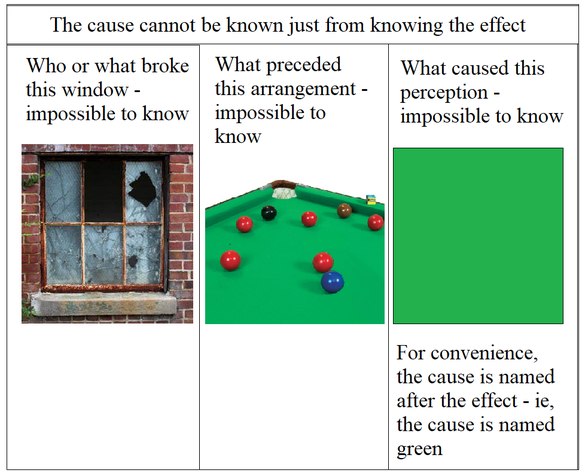

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that we gain all our information about a mind-independent world through our senses. The Direct Realist argues that just from a knowledge of our sensations, we are able to have a veridical knowledge of the cause of these sensations. I would argue that from knowing just an effect, it is impossible to directly know its cause.

We know we perceive the colour red, yet the Direct Realist argues that the cause of our perceiving red is a colour red existing in a mind-independent world. We know we perceive a circle and line, which are particular spatial relationships between individual points, and we know we perceive particular spatial relationships between these shapes, yet the Direct Realist argues that the cause of our perceiving spatial relations is the ontological existence of spatial relationships in a mind-independent world.

For PDR to be a valid theory, it must justify at the least that colours and spatial relations ontologically exist in a mind-independent world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Argument against Direct Realism

Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) says that we have direct cognition of the object "apple" as it really is in a mind-independent world. Therefore, for SDR, apples exist in a mind-independent world, whether they are perceived or not.

However, as the apple rots, at what exact moment in time in a mind-independent world does the apple disappear from existence. A human observer may judge when the apple disappears from existence, but what is there in a mind-independent world that determines when the apple disappears from existence ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?As Wittgenstein pointed out, somewhere in PI, pointing at something only works if the other folk around you understand that they have to follow the direction of your finger - and that is already to be participants in a sign language. — Banno

It follows that Wittgenstein's language game is incompatible with Semantic Direct Realism.

Definitions of Direct Realism

I defined Direct Realism as either:

1) Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) is a direct perception of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

2) Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) is an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

Wikipedia on Naive Realism writes: "According to the naïve realist, the objects of perception are not representations of external objects, but are in fact those external objects themselves."

You wrote that: "Direct realism is where what we talk about is the tree, not the image of the tree or some other philosophical supposition."

In summary, some definitions of Direct Realism are limited to perception, free of language, and some definitions require cognition, involving language.

However, as the argument from illusion makes too strong case against Phenomenological Direct Realism, Semantic Direct Realism remains the only likely possibility.

The difference between perception and cognition

In perception, the brain receives sensory input through the five senses which it processes as simple and complex concepts, simple concepts such as the colour green, and complex concepts such as a tree. In cognition, the brain combines these concepts using memory, reasoning and language to understand what has been perceived, enabling propositions such as "the tree is green".

As language is part of cognition, I can perceive things without needing a language. There are many things in the world that I perceive that I have no words for.

The act of pointing

I agree that I have been assuming that the word "tree" in language is pointing at a picture of a tree existing in a mind-independent world.

However, you note that the act of pointing is already part of the language game, meaning that what is being pointed at exists in a world, but the world of the language game, not a mind-independent world.

Wittgenstein in para 31 of PI writes that the act of pointing only works if the observer has previous knowledge of what is being pointed out:

"Consider this further case: I am explaining chess to someone; and I begin by pointing to a chessman and saying: "This is the king; it can move like this, . . . . and so on."—In this case we shall say: the words "This is the king" (or "This is called the 'king' ") are a definition only if the learner already 'knows what a piece in a game is'".

Therefore, words being used in the language game are not pointing out objects in a mind-independent world, but are pointing out objects existing within the language game itself

However, Semantic Direct Realism is the position that we have a direct cognition of "trees" as they really are in a mind-independent world, allowing us to make the statement that "trees are green" is true IFF trees are green in a mind-independent world.

As Wittgenstein's language game says that the statement "trees are green" does not point to something in a mind-independent world but rather points to something already existing in language, Wittgenstein's language game is incompatible with Semantic Direct Realism, which says that "trees are green" does point to something existing in a mind-independent world.

Summary

IE, Wittgenstein's language game is incompatible with Semantic Direct Realism. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Why would you submit this as an example as a counter to direct realism if you don’t have idea what it is countering? — Richard B

I gave my definition of Direct and Indirect Realism here.

Best answered by a Direct Realist, as I don't know of anything that a Direct Realist has direct cognition of that isn't a representation of something in a mind-independent world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Are you claiming that for the direct realist to be consistent with their position that when the person walks away, their height must appear the same the further they move away from the observer? — Richard B

Perhaps best answered by someone who believes in Direct Realism. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The other, a metaphysical theory positing “sense data” which is in principle private, unaccessible, and with un-unverifiable claims. Lastly, as I have been arguing irrelevant to the meaning of the language used. — Richard B

The Indirect Realist agrees that private experiences are private, but as Wittgenstein explains in para 293 of PI, language games work because private experiences drop out of consideration as irrelevant: "That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant." -

Is indirect realism self undermining?How can the Direct Realist justify that the colours red and blue exist in a mind-independent world.

The Direct Realist argues that they have direct cognition of the colours red and blue as they really are in a mind-independent world. meaning that the colours red and blue exist in a mind-independent world.

Red covers the range 625 to 750nm and blue the range 450 to 485nm.

In a mind-independent world, what determines that a wavelength of 650nm has something in common with a wavelength of 700nm, yet nothing in common with a wavelength of 475nm ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Defining Direct Realism.

Some Direct Realists argue for Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR), aka casual directness, a direct perception and a direct cognition of the object as it really is, and some argue for Semantic Direct Realism (SDR), aka cognitive directness, an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object as it really is.

The argument from illusion makes a strong case against PDR.

Supporters of SDR would argue that "Direct realism is where what we talk about is the tree, not the image of the tree or some other philosophical supposition."

However, it is equally true that "Indirect realism is where what we talk about is the tree, not the image of the tree or some other philosophical supposition."

As an Indirect Realist I directly see a tree, I don't see a model of a tree. Searle wrote "The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain". Similarly, the experience of seeing a tree does not have a tree as an object because the experience of seeing a tree is identical with the tree.

Something else is needed to distinguish Semantic Direct Realism from Indirect Realism.

One could write:

Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) is a direct perception of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) is an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

Indirect Realism is a direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in the world existing in the mind, with the belief that although there is no "tree" in a mind-independent world, there is something in a mind-independent world that has caused such perception and cognition. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?And as Wittgenstein pointed out in the first few pages of PI, you would thereby, already be participating in a language game, and so trying to explain meaning by making use of meaning. Then he cut to the chase: Stop looking for meaning, and instead look at use. — Banno

There are two aspects: i) does a potential word have a use, ii) given a word has a use, what does the word mean.

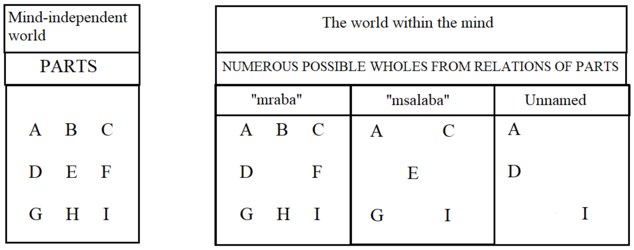

From my position of Neutral Monism, within a mind-independent world are elementary particles, elementary forces and space-time, and relations don't ontologically exist.

Does a potential word have a use

For the mind, some possible relations of the parts are useful within the language game and the broader life, and some aren't. For example the shapes "mraba" and "msalaba" are useful, but the shape with the parts ADI isn't. Only those shapes which are useful are named, and shapes which aren't useful are not named.

For example, the word "peffel", being part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower, has little use in either the language game or broader life, and cannot therefore be found in the dictionary.

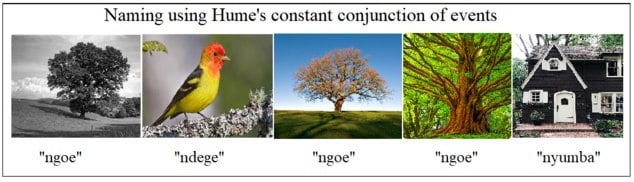

Given a word has a use, what does the word mean

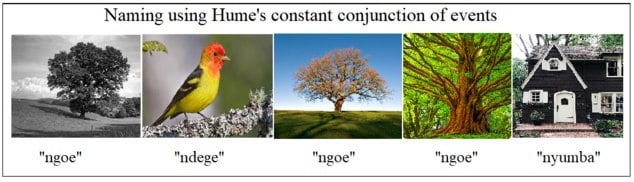

It is an undisputable fact that naming using Hume's constant conjunction of events works. It may not completely work first time as it is an iterative process, but it clearly works.

Given that the word "ngoe" has a use within the language game and broader life, what does "ngoe" mean. More broadly, what does "mean" mean.

Meaning is neither in the word "ngoe" or the picture of a ngoe, meaning is in the link between the word "ngoe" and the picture of a ngoe.

We cannot say that the word "ngoe" has a meaning, we cannot say that the picture of an ngoe has a meaning, but we can say that the link between the word "ngoe" and the picture of a ngoe has a meaning.

The link between the word and the picture is where the meaning resides.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum