-

Abortion - Why are people pro life?The fact that abortions are legal doesn't force you to do anything, you can choose to have the child. My main issue with pro-life is that your taking away a choice for people that don't share the same beliefs when having it the other way, everyone can do what they want. — Samlw

They believe that abortion is murder. Telling them that abortion should be a choice is, to them, telling them that murder should be a choice. Most of us don’t believe that murder should be a choice. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect Realists

I don't quite get the problem. Let's say that there's something hiding under my bed cover. I cannot see under my cover to see what it is; I can only see the bump in the cover (and maybe the cover moving). Any knowledge I have of the thing under my cover is at best an inference.

It's the same principle with things like Kant's transcendental idealism or indirect realism.

And then on the further extreme the idealist claims that there isn't anything under my cover; there's only the cover, which happens to have a bump (and maybe is moving). -

Why should we worry about misinformation?

So at least we agree with the principle that some speech shouldn't be allowed. The difficulty is in deciding exactly which speech shouldn't be allowed. -

Why should we worry about misinformation?

On the other hand it seems reasonable to punish people for knowingly false bomb threats. -

Why should we worry about misinformation?But why? — NOS4A2

Why is slander illegal? Why are bomb threats illegal? We criminalise certain speech because we believe that allowing them would do more harm than good. -

Why should we worry about misinformation?Only when it violates criminal code, like with slander and so on, there should be penalties.

And presumably the suggestion is that the criminal code should include such things as misinformation along with slander and so on. -

PerceptionYet part of what confuses these threads is that there really are colored objects outside the body, in the sense that there are really objects which reflect light in ways that allow them to be discriminated. — hypericin

If by "coloured objects" you just mean "objects which reflect light which cause colour sensations" then sure. But that's dispositionalism, not naive colour realism.

Moreover they really do look the way they do: appearing this way (to humans) is a stable, mind independent property (just not independent of all minds, it is like a social reality) — hypericin

Yes, and stubbing one's toe really is painful. But pain is still a sensation. -

PerceptionI think of sensations as events in the body, but colored object appear outside of it. — NOS4A2

And this is where you're making a mistake. Visual sensations are events in the body (specifically events in the visual cortex). Depth is a characteristic of visual sensations, and so it seems as if there are coloured objects outside the body. But this is as misleading as phantom limbs.

You appear to be under the impression that visual perception is fundamentally different to other modes of perception, such as pain, smell, and taste. It really isn't. Each perceptual system simply involves different organs responding to different stimuli eliciting different types of sensations.

I don’t think believing what one is told or accepting an argument from authority is particularly rational — NOS4A2

Believing what scientists say about what their scientific studies have determined about the world (including perception) is rational. It is rational to believe in the Big Bang, evolution, atoms, electromagnetism, superposition, and so on, even if any of it conflicts with "common sense", and even if one hasn't carried out the experiments oneself. -

PerceptionWhy would we need to change the properties of the object if color is not a property of the object? — NOS4A2

We need to change how the object reflects light because the wavelength of the light that stimulates the eyes is what determines the type of colour sensation elicited.

Pain is a sensation, it hurts to put my hand in very hot water, I add cold water to reduce the temperature, and so I no longer feel pain when I put my hand in.

Besides, sensations aren’t red any more than the word “red” is. Sensations or experiences do not have any properties to begin with. If we are to abandon common sense and the world for pseudo-objects and things without properties we're going to need much more than that. — NOS4A2

I don't understand what you're trying to say here. Do you accept that pain is a sensation? Do you accept that a bitter taste is a sensation? I am simply pointing out that colour is another type of sensation, specifically a visual sensation. This may not be "common sense", but common sense does not determine the facts, and in this case common sense conflicts with the scientific evidence. I trust the scientific evidence.

If you want to reject the scientific evidence in favour of common sense then go ahead, but it's the less rational position to take. -

PerceptionWhat we do with paints, phosphors, pigments, suggest that the color is out there among the surfaces of the objects these adjectives are meant to describe. — NOS4A2

We just use those things to change the way an object’s surface reflects light. That does not suggest that colour is a mind-independent property of the object’s surface.

Perhaps you could explain which (if any) of these you believe:

1. “the apple is red” means “the apple reflects ~700nm light”

2. The apple is red because it reflects ~700nm light

3. The apple reflects ~700nm light because it is red

On the other hand, there is no indication color sensations exist. — NOS4A2

Yes there is. Dreams, hallucinations, variations in colour perception (e.g. the dress), and studies such as this. This is why James Clerk Maxwell in On Colour Vision (1871) said "it seems almost a truism to say that color is a sensation".

And as the SEP article on colour explains:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess. -

PerceptionIt would be helpful if colour realists explain which of these they believe:

1. “the apple is red” means “the apple reflects ~700nm light”

2. The apple is red because it reflects ~700nm light

3. The apple reflects ~700nm light because it is red -

Perceptioncolored objects occur outside the body in a space independent of the mind. — NOS4A2

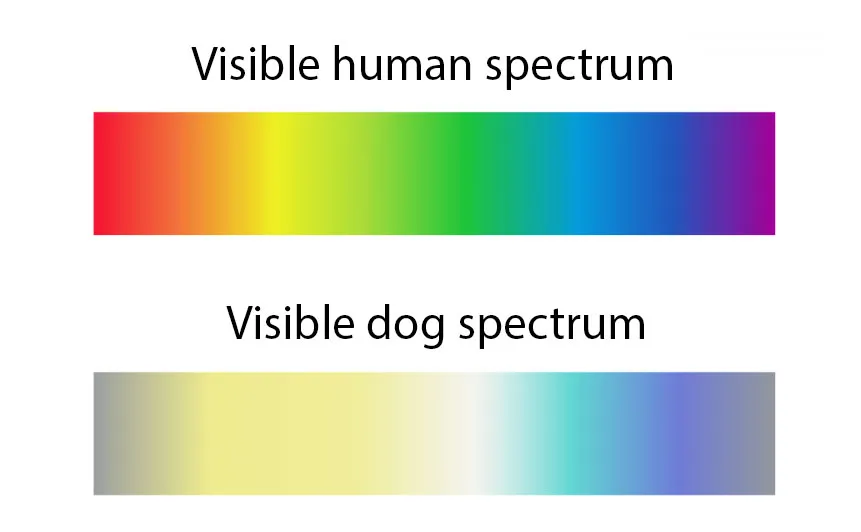

Objects outside the body just reflect different wavelengths of light. This light causes one type of colour sensation in humans and another type of colour sensation in dogs.

Color is a fiction. — NOS4A2

No it’s not, it just isn't what you claim it to be.

I don't see how it is useful to distort the picture with a fiction. — NOS4A2

Your reasoning is akin to arguing that because pain is not a mind-independent property of fire then it is not useful and a distortion and a fiction to feel pain when we put our hands in the fire. -

PerceptionThe eagle has 20/5 eyesight, more rods and cones, and see much better. According to color factionalism they invent color, too, and somehow paint the images with their brain, but why would animals with such great sight distort their sight with color? — NOS4A2

It's clearly useful to visually distinguish objects which reflect 400nm light and objects which reflect 700nm light. Colour sensations is how we do that.

Take this for example:

It's not that either humans or dogs (or neither) is seeing the "correct" (mind-independent) colour when looking at an object that reflects 500nm light; it's just the case that 500nm light causes different colour sensations for humans and dogs. -

PerceptionNo, just that it is possible to see thing more accurately, for instance if the world is without color, maybe it would better to see it without color. Why would a species need color? — NOS4A2

Is it possible to smell and taste things more accurately? Does the world contain smell and taste even when we're not smelling and tasting things? -

Perceptionif the world is without color then I suppose a scene of greys is what it must look like. — NOS4A2

You seem to be under the impression that there’s a way things look distinct from the way things look to us. That makes as much sense as saying that there’s a way things taste and smell and feel distinct from the way things taste and smell and feel to us.

Vision isn’t special. -

PerceptionI was including black, white, and grey as colours. But if we're excluding them and NOS4A2 is asking what the world looks like to someone with complete achromatopsia, then it would look black, white and grey.

-

PerceptionI just mean seeing it without the sensation of color. What do you suppose it looks like? — NOS4A2

I don't even know what a colourless visual sensation could be, and so I think without colour sensations you'd just be blind. -

PerceptionPerhaps we would be able to numb the sensation of color like we could the sensation of pain, and see the world how it really looks. — NOS4A2

Not sure what you mean by "how it really looks", just as I wouldn't be sure what you'd mean by "how it really smells" or "how it really tastes".

Is the world outside your head without color in your view? — NOS4A2

Yes, and without smell and taste and pain. -

PerceptionSorry - is your claim now that pain is also a fiction? :chin: — Banno

No, and nor is my claim that colour is a fiction. My claim is that pain and colour are sensations, and the fiction is that colour is not a sensation but a property of the ball.

And much like "stubbing one's toe is painful therefore pain is not a sensation" is a non sequitur, so too is "the ball is red therefore colour is not a sensation". -

PerceptionThe ball is red. — Banno

And stubbing one's toe is painful, but pain is still a sensation. We've been over this so many times. Your reasoning is a non sequitur. -

PerceptionI'm trying to understand why it matters in this discussion whether our neuronal response to light is altered by our language skills. — Hanover

Maybe that's true, but I'm more arguing against those who seem to be saying that because we say such things as "the box is red" then it must be that the colour red is a property of the box and not a property of our bodies. -

Perception

We see a red box and a blue box. The colour is the relevant visual difference between the two. I don't think that this visual difference has anything to do with language. The difference is entirely in how the boxes reflect light and then how our body responds to that light. -

PerceptionThat is, if I see a cardinal, I don't just see the red of the bird, but I see the whole bird and I also have all sorts of thoughts about what that thing can do and what it is at the same time. I don't just get a raw feed of red. — Hanover

Sure, but I don't think all that other stuff has anything to do with the colour, and the discussion is about colour. -

PerceptionThat Michael might allow interpretation of the external object by the sense organs alone and not allow it to also be interpreted by language just seems an odd limitation (if that's at all what he's even saying, as that doesn't seem correct). — Hanover

All I am saying is that a deaf illiterate mute can see the difference between a red box and a blue box. That visual distinction has nothing to do with language and everything to do with what the brain does (in response to what the eyes do in response to what the light does in response to what the box does).

Or for a more self-evident example, I can see the difference between two shades of red despite not having an individual name for each shade.

All this talk of language is utterly irrelevant. -

Perception[Michael] was never willing to try to explain how his conclusions followed from "the science." — Leontiskos

I have simply quoted what the scientists have said about colour. I'll do it again for you:

Colour is a sensation. — James Clerk Maxwell

For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain power and disposition to stir up a sensation of this or that Colour. — Isaac Newton

Color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights. — Stephen Palmer

As the SEP article on colour explains:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess.

If you disagree with the science then simply say so, but don't pretend that the science isn't saying what the science is saying. How much more explicit does the above need to be for you?

instead of making arguments for his position he would only ultimately make arguments from authority from "the science." — Leontiskos

Yes, because the scientists are the ones who have carried out the experiments to figure out how the world works, so they better know what they are talking about. You can't determine what colours are just by sitting in your room and using a priori reasoning. -

PerceptionThe bolded word is where Michael oversteps. Things in the word, and the people around us, also have a say in what colours we see. — Banno

I haven't claimed otherwise. I have explicitly stated that ~700nm light is the usual cause of red colour experiences (because it is the usual cause of the brain activity that corresponds to red colour experiences). -

PerceptionWhen a shadow falls over a ball we do not say that the color of the ball has changed, because we differentiate our visual perception of the ball from the ball's color. — Leontiskos

The ball just has a surface layer of atoms with an electron configuration that absorbs and re-emits particular wavelengths of light; these wavelengths being causally responsible for the behaviour of the eye and in turn the brain and so the colour experienced.

Physics and neuroscience has been clear on this for a long time.

We might talk about the ball as having a colour but that's a fiction brought on by the brain's projection and the resulting (mistaken) naive colour realist view of the world. -

PerceptionBut if seeing is using the eyes to perceive the environment, that isn’t sight. That’s all I’m saying. — NOS4A2

And as I've said, you're welcome to only use the verb "to see" in that sense if you like, but there's nothing wrong with the rest of us being more inclusive in how we use such language. -

Perception

All that is required to have a visual experience is for there to be the appropriate neural activity in the visual cortex, and all that is required to have an auditory experience is for there to be the appropriate neural activity in the auditory cortex.

Most of the time this neural activity is a response to sensory stimulation of biological sense organs, but sometimes it is a response to other things, whether those be artificial sensory aids, drugs, sleep, or mental illness. -

PerceptionNo amount of glasses can help the those with total blindness see, however. — NOS4A2

But other mechanisms such as a cortical visual prosthesis can help (or will be able to help in a few decades). Much like a cochlear implant helps where an ear trumpet can't. -

Perception

They are seeing in the sense of having a visual experience but not seeing in the sense of responding to and being made aware of some appropriate external stimulus by way of their eyes, much like the schizophrenic is hearing in the sense of having an auditory experience but not hearing in the sense of responding to and being made aware of some appropriate external stimulus by way of their ears. -

PerceptionYou've claimed that the "hears" in "hears voices" is just like the "hears" in ordinary predications about hearing — Leontiskos

No I haven't. -

PerceptionNo, "hears voices" is a euphemism for "hallucinates." You are confusing yourself. — Leontiskos

I'm not confusing myself because I haven't claim that "hearing voices" isn't a euphemism for "hallucinate".

I am simply saying that it is ordinary in English to use the verbs "to see" and "to hear" in a much more inclusive manner than the more restricted sense that you and NOS4A2 insist on. -

PerceptionIf they can hear, why do they have a cochlear implant? — NOS4A2

They hear because of the cochlear implant, much like I can see the words on the screen because of my glasses. -

PerceptionIf they were reducible to the brain then everyone with a brain would be able to see and hear — Leontiskos

That doesn't follow. -

Perception

It's not equivocation to say that the schizoprenic hears voices. That's just the ordinary way of describing the phenomenon.

Verbs like "to see" and "to hear" don't just refer to so-called "veridical" perception. -

PerceptionThe environmental stimulus and the means with which it interacts with a fully-functioning sensory organ is a large part of acts such as “seeing” and “hearing”, and ought not be confused with some other stimulus. Stimulating a brain with some of the methods indicated is just an artificial way to illicit some of the biological effects of an actual, natural stimulus, but is in fact not the same act. — NOS4A2

Why does that matter? It is still normal to describe someone with a cochlear implant as hearing things, and the same for those with an auditory brainstem implant.

If you only want to use the words “see” and “hear” for those with normally functioning sense organs then you do you, but it’s not wrong for the rest of us to be more inclusive with such language. -

PerceptionAnd perhaps more fittingly than a cochlear implant is an auditory brainstem implant.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum