-

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Maybe it has something to do with the information stored in their brains. — Harry Hindu

Yes, but if eliminative materialism is correct then this is properly understood as "it has something to do with the existence and configuration and activity of the brain's neurons".

And like every other physical object in the universe, the brain's neurons' behavior is causally influenced by prior physical events, and in this particular case these prior physical events are often the stimulation of the sense organs. -

Free Speech - Absolutist VS Restrictive? (Poll included)Yes, but why does each person respond to those same lights, sounds, smells, etc differently? — Harry Hindu

Slightly different biologies. Your eyes are not identical to my eyes and your brain is not identical to my brain.

Exactly - which means that because people respond to the same lights, sounds, smells, etc. differently there must be some other process between some speech being made and one's actions that manifests as that difference in actions after hearing a speech. — Harry Hindu

Yes, that thing being the body and brain of the listener/actor. But it's still the case that the action is a causal response to the stimulation (assuming that eliminative materialism is correct and so that libertarian free will does not exist).

How two different computers respond to their "A" key being pressed depends entirely on their internal mechanics. One computer may display a letter on the screen and the other may emit a noise. Either way, the computer's behaviour is a causal response to someone pushing the "A" key. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?On rigid designators, what does it mean for an object in one possible world to be the same object as an object in a different possible world? Is it simply a stipulation?

The question is especially relevant if we claim that the same object can have different properties in different possible worlds. Does it make sense to say that there's a possible world where I'm a black man named "Barack Obama" and who served as the 44th President of the United States? What does it mean for this person to be a possible version of me rather than a possible version of you or a possible version of the actual Barack Obama? -

Knowledge is just true information. Isn't it? (Time to let go of the old problematic definition)

From here you said:

Indeed, if we came across someone who said "I know that there is water in the tap", but became confused when asked to locate and turn the tap on in order to obtain a glass of water, we might well conclude that they said they knew but really didn't.

There seems to be a pretty good argument that "knowing that" is a type of "knowing how".

So given that I say "I know that in a few billion years the Sun will expand and consume the Earth" what is the "knowing how" (comparable to using the tap to fill a glass of water) that demonstrates that I do in fact know what I claim to know?

But on the example of the tap:

1. I know that the tap is working

2. I know that the tap isn't working

3. I know how to use a tap

4. I know how to prove that the tap is working

5. I know how to prove that the tap isn't working

6. I know how to assert the English sentence "(I know that) the tap is working"

7. I know how to assert the English sentence "(I know that) the tap isn't working"

It's entirely possible that (3)-(7) are all true but that (1) and (2) are both false. Therefore (1) and (2) are distinct from (3)-(7). -

Knowledge is just true information. Isn't it? (Time to let go of the old problematic definition)You just did. — Banno

You're going to have to elaborate. Otherwise it seems that you're just saying that knowing that p is equivalent to knowing how to write "I know that p". Which would be such a cop-out. -

Knowledge is just true information. Isn't it? (Time to let go of the old problematic definition)There seems to be a pretty good argument that "knowing that" is a type of "knowing how". — Banno

I know that in a few billion years the Sun will expand and consume the Earth.

Not really sure how to make use of this information, but I know it all the same. -

Knowledge is just true information. Isn't it? (Time to let go of the old problematic definition)But information doesn't become knowledge until it's been verified and incorporated with our data base.

Truth is not the issue. The issue is the difference between belief and knowledge. When you say "justified true belief", that's the same as a belief that has been verified so that it can become knowledge. That's far beyond a simple fact "true information". — Vera Mont

I'm not sure if verification is necessary. It seems like a very strict requirement. If a stranger tells me that their name is John, do I have to verify this (e.g. by checking their ID) before I can be said to know their name? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderBorn something he (or she, I don't indulge or humor nonsense let alone keep track of such) wasn't. — Outlander

Which is what? Does the transgender man believe himself to be a fish? I need an actual example of a delusion.

All of that is fine, well fine enough, as there's more important things to deal with, up until the point that one considers it logical to permanently and irreversibly alter one's non-disabled and fully healthy body and form, most critically those under the age of what is socially considered a functional and legal adult.. That is what you're blatantly avoiding, my good sir. And I believe you are doing such intentionally for whatever reason that is again up to the public writ-large to determine why and perhaps what should be done as a result. — Outlander

Not every transgender person has gender dysphoria, and according to this, "in studies that assessed transgender men and women as an aggregate, chest surgery has been reported at rates between 8–25%, and genital surgery at 4–13%".

And whether you like it or not, hormone therapy and surgery can be effective treatments. You can't just pretend that gender dysphoria isn't real or can be safely ignored or can only be treated by psychotherapy.

As for "permanently and irreversibly alter[ing] one's non-disabled and fully healthy body and form", well so too is a salpingectomy, but if a woman does not wish to have children and opts to have one then that's her concern and nobody else's, and they ought be allowed to have one. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderThat you're something you're not. — Outlander

So what does the transgender man falsely believe himself to be?

Dude. That's literally what the whole discussion is about. — Outlander

No, it isn't. Transgender people don't just "wake up one day wanting different body parts for no logical reason".

I'm going to quote from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_identity both for you and for @Harry Hindu because it seems that neither of you actually understand the issue at all.

It is widely agreed that core gender identity is firmly formed by age 3. At this point, children can make firm statements about their gender and tend to choose activities and toys which are considered appropriate for their gender (such as dolls and painting for girls, and tools and rough-housing for boys), although they do not yet fully understand the implications of gender. After age three, it is extremely difficult to change gender identity.

Martin and Ruble conceptualize this process of development as three stages: (1) as toddlers and pre-schoolers, children learn about defined characteristics, which are socialized aspects of gender; (2) around the ages of five to seven years, identity is consolidated and becomes rigid; (3) after this "peak of rigidity", fluidity returns and socially defined gender roles relax somewhat. Barbara Newmann breaks it down into four parts: (1) understanding the concept of gender, (2) learning gender role standards and stereotypes, (3) identifying with parents, and (4) forming gender preference.

...

Although the formation of gender identity is not completely understood, many factors have been suggested as influencing its development. In particular, the extent to which gender identity is determined by nurture (social environmental factors) versus biological factors (which may include non-social environmental factors) is at the core of the ongoing debate in psychology known as "nature versus nurture". There is increasing evidence that the brain is affected by the organizational role of hormones in utero, circulating sex hormones and the expression of certain genes.

Social factors which may influence gender identity include ideas regarding gender roles conveyed by family, authority figures, mass media, and other influential people in a child's life. The social learning theory posits that children furthermore develop their gender identity through observing and imitating gender-linked behaviors, and then being rewarded or punished for behaving that way, thus being shaped by the people surrounding them through trying to imitate and follow them.

Large-scale twin studies suggest that the development of both transgender and cisgender gender identities is due to genetic factors, with a small potential influence of unique environmental factors.

...

Some studies have investigated whether there is a link between biological variables and transgender or transsexual identity. Several studies have shown that sexually dimorphic brain structures in transsexuals are shifted away from what is associated with their birth sex and towards what is associated with their preferred sex. The volume of the central subdivision of the bed nucleus of a stria terminalis or BSTc (a constituent of the basal ganglia of the brain which is affected by prenatal androgens) of transsexual women has been suggested to be similar to women's and unlike men's, but the relationship between BSTc volume and gender identity is still unclear. Similar brain structure differences have been noted between gay and heterosexual men, and between lesbian and heterosexual women. Transsexuality has a genetic component.

Research suggests that the same hormones that promote the differentiation of sex organs in utero also elicit puberty and influence the development of gender identity. Different amounts of these male or female sex hormones can result in behavior and external genitalia that do not match the norm of their sex assigned at birth, and in acting and looking like their identified gender.

For better or for worse, societies tend to establish gender roles – norms of behaviour deemed appropriate or desirable for individuals based on their biological sex, but norms of behaviour which don't actually have anything to do with biological sex at all.

In the very early years of human development – and in particular at a time when we're unlikely to even be aware of sex organs different from our own – we come to identify as "belonging" to one of these gender roles. The particular gender role that we come to identify as belonging to is determined in part by our genetics, hormones, and brain structure.

And sometimes a biological boy comes to identify as belonging to the gender role typically associated with biological girls, and sometimes a biological girl comes to identify as belonging to the gender role typically associated with biological boys – and this is not wrong because these gender roles are a social construct that have no direct connection to DNA or reproductive organs at all. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderBut when you grow up and start physically and irreversibly altering your body over a delusion — Outlander

What delusion?

Some dude who just woke up one day wanting different body parts for no logical reason, that's just not something that needs to be taken seriously. — Outlander

It's also not something that actually happens. This is a ridiculous strawman. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderDefine "artificial". — Harry Hindu

The result of genital surgery.

Which bathroom should an android with an artificial penis use? — Harry Hindu

Androids aren't people, they're machines. So there's no "should" or "shouldn't". We can do whatever we like. We could make androids use bathrooms only for androids or we could make them use whichever bathroom is closest or we could make androids with an artificial penis use the men's bathroom.

Or we could just not create androids that need to urinate?

What is the point of this question?

It doesn't show anything specific, which is what I'm asking for. — Harry Hindu

Because there is no specific thing. Society and culture is complex. The social and cultural differences between men and women (or third genders) changes over time and from place to place. And again, there's no set of necessary and sufficient conditions even at a singular time and place.

Do you deny that there are social differences between men and women, independent of their karyotype and genitals? Are we are gender-blind outside of reproduction and reproductive health? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderAnd some people that are not transgender have had genital surgery, as you have pointed out and apparently forgotten. So what does gender status have to do with using the bathroom if gender has nothing to do with biology? Why is it so important that trans people get to use the bathroom rather than the non-trans that have had surgery? It must be because you continue to conflate sex with gender in one moment then claim they are separate in another. — Harry Hindu

What are you talking about?

You claimed that sex parts dictate which bathroom one can use such that people with a penis use one bathroom and people with a vagina use another bathroom.

I just want to know if you accept that a transgender man with an artifical penis should use the men's bathroom.

It's a simple "yes" or "no" answer.

Aren't they saying they are psychologically and culturally male/female? Isn't that the point of contention here? I'm still waiting on specific examples. — Harry Hindu

I've linked to various articles that explain gender, gender roles, gender expression, and gender identity. Do the reading. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderYour conflating sex and gender again. — Harry Hindu

No, I'm not. I am simply acknowledging the fact that some transgender people have genital surgery. According to this, 25-50% of transgender men have genital surgery and 4-13% of transgender women have genital surgery.

So, if bathroom usage is dictated by sex parts – which is your claim, not mine – then do you accept that transgender men who have had genital surgery should use the men's bathroom and transgender women who have had genital surgery should use the women's bathroom?

By having genital surgery the trans-person is asserting their gender is determined by their sex. — Harry Hindu

No they're not. The transgender woman is fully aware that she is biologically male and the transgender man is fully aware that he is biologically female.

The very fact that they identity as being transgender is an acknowledgement that their gender is not the typical gender of their biological sex.

Now, what about trans people that haven't had surgery? Which bathroom should they use? — Harry Hindu

Transgender women should use the women's bathroom and transgender men should use the men's bathroom.

And what are they saying determines their gender - which social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects are they referring to - specifically? — Harry Hindu

There's no list of necessary and sufficient conditions. I've linked you to the relevant places that explain it in more detail:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_role

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_expression

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_identity -

Disambiguating the concept of genderSo, just to be clear, in talking about people that have had genital surgery, we're talking about intersex people, not trans-gendered people. — Harry Hindu

And what about trans people who have had genital surgery? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderyou are the one going on about bathrooms — Harry Hindu

Because that’s what we were both discussing. You said "we separate bathrooms by sex because it is an area where we uncover our sex parts."

I just want to understand how artificial sex parts factor into your separation.

I'm talking about the relationship between gender and sex. — Harry Hindu

And that's been addressed several times before.

Sex "is the biological trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes."

Gender "is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender."

In most cases one's gender is determined by one's sex, but given the existence of transgender people – and societies with more than two genders – this is not a necessity. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderYou are contradicting yourself. — Harry Hindu

No, I’m not.

It’s a very simple question, Harry. If you are in charge of deciding who is allowed to use which bathroom, then would you require that trans men who have had genital surgery and now have an artificial penis use the men’s bathroom or the women’s bathroom? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderIf you're not conflating gender and sex then why are you calling people who modified their sexual biology trans-gender? — Harry Hindu

I’m not.

You claimed that the reason we have separate bathrooms for men and women is because men and women have different sex organs. And it is a simple fact that some trans people have genital surgery. So I’m asking you which bathroom they should use after having genital surgery.

In proposing unisex bathrooms you are taking away the trans-gender person's reasons for having surgery in the first place - to affirm their gender — Harry Hindu

I’m not. -

Disambiguating the concept of gender...but it would not include most trans-people as most trans have not had surgery. So you would still force a man wearing a dress into the men's bathroom. — Harry Hindu

I’m not the one claiming that we ought divide bathrooms by sex organs; you are.

I’m simply pointing out that if we divide bathrooms by sex organs then it makes sense to allow trans men who have had surgery to use the men’s bathroom and trans women who have had surgery to use the women’s bathroom.

Surely one’s karyotype is irrelevant, as are the gentitals one was born with (and no longer have)? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderSo women should stand aside as usual. — Malcolm Parry

I have no idea what you mean here.

I’m simply pointing out the fact that it is safer for everyone if trans people are allowed to use their preferred bathroom.

So either you disagree with the facts or you don’t actually care about people’s safety at all. Perhaps you’re just using that as a dog whistle to push an anti-trans agenda. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderI'm saying (a) is false — Malcolm Parry

The evidence shows otherwise.

men should not be allowed in women's exclusive spaces — Malcolm Parry

Yet again with the equivocation.

The claim is that no bathroom should be exclusive to a single biological sex. If bathrooms are to be divided then they ought be divided by gender identity. As such, there are “female gender bathrooms” and “male gender bathrooms”, with “female gender bathrooms” exclusive to both cisgender and transgender women and “male gender bathrooms” exclusive to both cisgender and transgender men.

The studies show that this is the safer option for everyone. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderAre you saying women are stupid to feel that they should exclude men from their exclusive places? — Malcolm Parry

I’m saying that:

a) cisgender women are not put at risk by trans-inclusive bathroom policies, and

b) trans people are put at risk of abuse when forced to use the bathroom contrary to their gender identity

Are you saying that (a) and/or (b) are false? Or are you saying that you don’t care that they’re true? -

Disambiguating the concept of gender

No link between trans-inclusive policies and bathroom safety, study finds

There is no evidence that letting transgender people use public facilities that align with their gender identity increases safety risks, according to a new study from the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. The study is the first of its kind to rigorously test the relationship between nondiscrimination laws in public accommodations and reports of crime in public restrooms and other gender-segregated facilities.

“Opponents of public accommodations laws that include gender identity protections often claim that the laws leave women and children vulnerable to attack in public restrooms,” said lead author Amira Hasenbush. “But this study provides evidence that these incidents are rare and unrelated to the laws.”

...

“Research has shown that transgender people are frequently denied access, verbally harassed or physically assaulted while trying to use public restrooms,” according to Jody L. Herman, one of the study’s authors and a public policy scholar at the Williams Institute. “This study should provide some assurance that these types of public accommodations laws provide necessary protections for transgender people and maintain safety and privacy for everyone.” -

Disambiguating the concept of genderyou wish to allow males into female spaces — Malcolm Parry

I wish to allow transgender women to use the women’s bathroom and transgender men to use the men’s bathroom.

playing down the concerns females have at males gaining access to to places where females feel vulnerable and uncomfortable in the presence of males. — Malcolm Parry

I don’t play it down. I just also acknowledge that trans women feel vulnerable and uncomfortable using the men’s bathroom, that trans men feel vulnerable and uncomfortable using the women’s bathroom, that trans people are at a greater risk of abuse when forced to use the bathroom contrary to their gender identity, and that despite the dog whistle, cisgender women are not put at risk by trans-inclusive bathroom policies. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderYou are denying this difference and wish to play down the woman's experience in modern society. — Malcolm Parry

I’m not playing down women’s experiences. I’m simply explaining that “women’s experiences” is not reducible to “the experience of humans with an XX karyotype, ovaries, and a vagina.”

Women as a gender is distinct from women as a sex, even if they almost always correspond. The fact that they almost always correspond has caused you to mistakenly conflate the two. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderI doubt many men would care. — Malcolm Parry

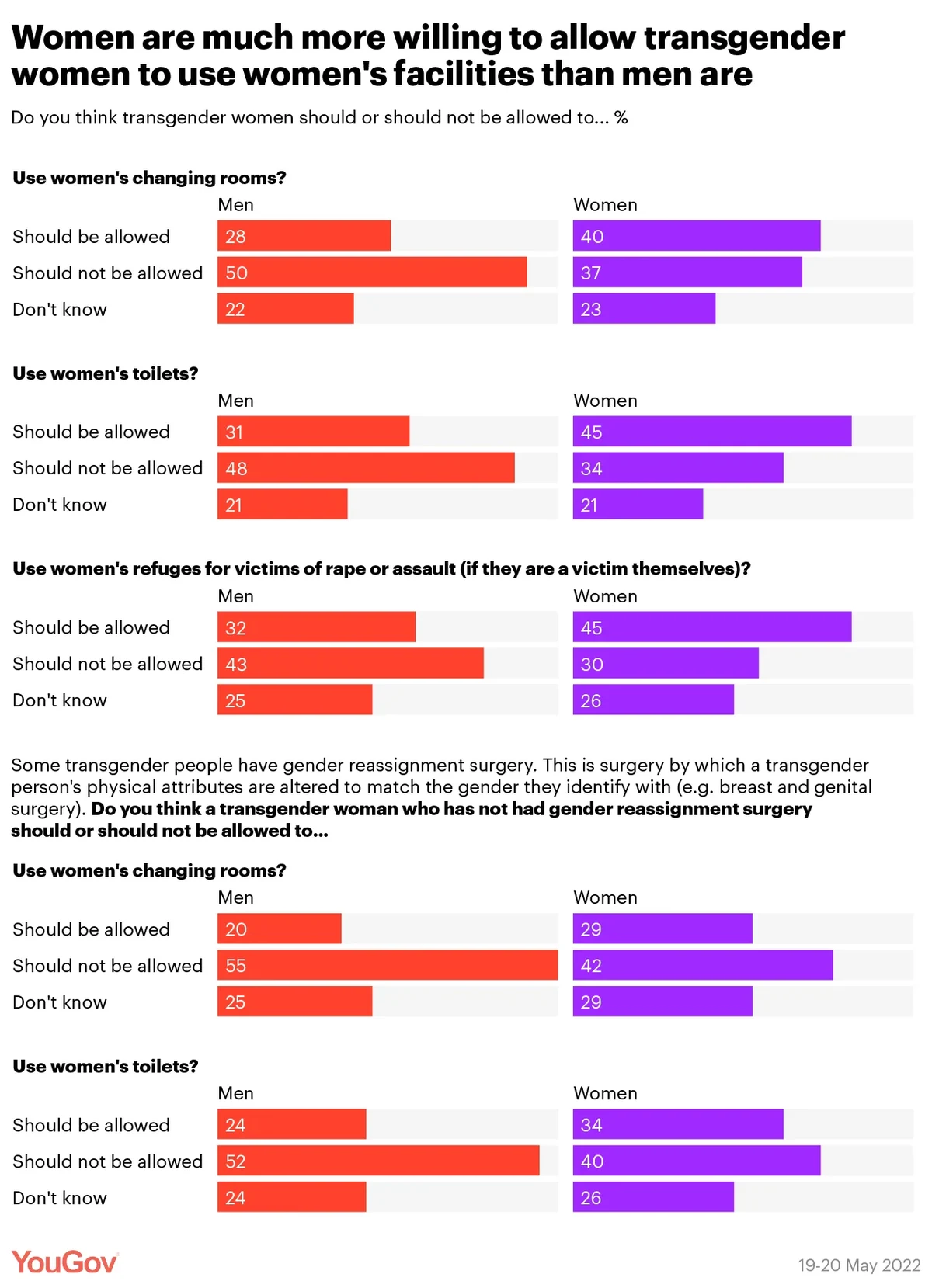

And yet the poll you linked to says that 51% of men oppose trans men using the men's toilets (with only 33% in support). So evidently most men do care.

The person's biology has a huge influence on the development someone. — Malcolm Parry

Yes, but there's more to biology, and in particular neurology, than just sex chromosomes and genitals.

Men growing up will not have the same experiences women. — Malcolm Parry

And transgender women growing up will not have the same experiences as cisgender men, and transgender men growing up will not have the same experiences as cisgender women. It's not all about sex chromosomes and genitals. I don't know why you can't accept this. We are not merely biological automatons. We are conscious organisms with complex psychologies and personal identities, with gender identity "develop[ing] surprisingly rapidly in the early childhood years, and in the majority of instances appears to become at least partially irreversible by the age of 3 or 4." -

Disambiguating the concept of genderThe gender is reflection of the societal differences between the sexes. — Malcolm Parry

And these societal differences have nothing to do with biology. Gender is distinct from sex.

read the link — Malcolm Parry

Ah, so public opinion changed between 2022 and 2024. It's interesting that there's such a large swing in just two years. There's even a majority opposition to trans men using the men's bathroom, and again with men being much less tolerant than women. But speaking as a man, I don't care what other men think. Trans men ought be allowed to use the men's bathroom.

The age breakdown is also interesting, with the majority of 18-24 year olds supporting trans people using their preferred bathroom, and every other age group being the opposite. The other biggest determinants are who you voted for (more Lib Dems support it than oppose, whereas more Conservatives oppose it than support) and whether or not you know a trans person.

I wonder how much of the opposition is reminiscent of historical (and even current) homophobia and gay panic. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderAllowing men into women's bathrooms. — Malcolm Parry

When including transwomen who have had gender-affirming surgery, 45% of women say that transwomen should be allowed to use the women's bathroom compared to 34% who say they shouldn't (with 21% saying they don't know). 45 is greater than 34.

So this ties into my claim to Harry Hindu that we ought to at least let trans women who have had bottom surgery use the women's bathroom and trans men who have had bottom surgery use the men's bathroom.

But what's most interesting I think is that men are much less tolerant of transwomen using women's facilities than women are. I don't know if that's because men are in general less tolerant of transgender people or because they're white knighting. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderGender is the societal differences between the sexes. — Malcolm Parry

These societal differences are distinct from any biological differences, so clearly gender is distinct from sex. And people can identify as belonging to the gender that is not typical for their biological sex. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderLooks like the majority of women disagree with you. Do you dismiss that? — Malcolm Parry

Disagree with me on what? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderDismissing their concerns and shared experience. — Malcolm Parry

I'm not dismissing it.

But as it may interest you:

-

Disambiguating the concept of genderYou want males to enter their exclusive places. Is that not dismissing it? — Malcolm Parry

I am questioning the claim that certain bathrooms ought be exclusive to biological women.

I think that is a meaningless concept and dismisses what it is to be female. — Malcolm Parry

So you deny the reality that gender is distinct from sex? -

Disambiguating the concept of genderYou have dismissed the concerns of females in spaces where they are may feel awkward and vulnerable. The toilet is one of those places. — Malcolm Parry

I'm not dismissing it.

I reject the notion that man can become a woman. — Malcolm Parry

Again with the equivocation. Nobody is claiming that a biological man can become a biological woman or that a biological woman can become a biological man. What is claimed is that biological men can have a female gender identity, that biological women can have a male gender identity, and that certain social divisions ought be made by gender identity rather than biological sex. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderSeparate bathrooms is not just about sex organs and the place of females in society is not based just on sex organs. — Malcolm Parry

Harry Hindu is the one who said "we separate bathrooms by sex because it is an area where we uncover our sex parts" and so I am simply addressing the implications of this reasoning.

I find the whole dismissive attitude to female experience in society quite sad. — Malcolm Parry

I'm not dismissing it. But you certainly seem to be dismissing transgender experience.

You continue to think that transgender women are psychologically, socially, and culturally equivalent to cisgender men simply because they share the same set of chromosomes, gonads, and genitals. Your view is mistaken.

but there are still threats to females and unique challenges for females — Malcolm Parry

And there are threats to and unique challenges for transgender men and transgender women. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderHere we go again with conflating gender with biology, which leaves out those that have not had surgery. — Harry Hindu

I’m not conflating gender with biology. I am simply pointing out that if we separate bathrooms according on one’s sex organs, as you say we should, then it makes sense to allow those with an artificial penis to use the same bathroom as those with a natural penis and to allow those with an artificial vagina to use the same bathroom as those with a natural vagina.

Included in those with artificial genitals are trans people who have had surgery, intersex people who have had surgery, and cisgender people who have had surgery after an unfortunate accident with a buzz saw.

I have also asked for examples of gender as something psychological. I have already shown an example of gender as something cultural (sexist tropes). So I'm still waiting on you to provide an example of what you mean. Just tell me what you mean when you assert you are a man or woman? Why can't you do that simple thing? — Harry Hindu

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_identity

I'm not even saying they're wrong. I'm asking a question about how they can they reach the conclusions they have when the evidence they provide doesn't include necessary information to reach that conclusion and is contradictory. I asked how it logically follows that these distinctions qualify as sexual differences if they occur across both sexes. This is required information and the fact that it is not included is suspicious. The fact that I cannot find the information is also suspicious - kind of like how that study that showed the negative effects of transitioning children was swept under the rug. I have shown evidence that scientists are not always truthful and can be manipulated by politics as much as anyone else, yet you keep pleading to authority when I have shown that the authority you are pleading to has not provided all the necessary information and has been caught keeping necessary information out of the public view.

And when we live in an age of disinformation propagated by the authorities on both sides of the political spectrum, why would you not at least question authority than hides necessary information to claim what they are claiming? — Harry Hindu

If you don’t trust what the experts have determined then I don’t see how I can help. As I alluded to before, I can no more prove that there are sex differences in psychology than I can prove that humans evolved via natural selection from single-celled organisms. All I can do is point you in the direction of the research. What you do with that is out of my control. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderWell shoot why not a fourth gender? Or a fifth. Or a sixth. Or a 12th while we're at it! This is not slippery slope fallacy, this is what people will attempt to argue for. — Outlander

Well, yes. The Bugis society recognizes five genders, and has so for at least 600 years.

A limit must be drawn lest mankind wander forever lost in a dystopian deluge of his own making. — Outlander

Why? There's no singularly correct way for society and culture to be structured. You seem to have some Western bias, thinking that it's only appropriate to group people according to biological sex and not in other ways. -

Disambiguating the concept of gender

What I mean is that tuxedos being “men’s clothes” and dresses being “women’s clothes” is entirely a social and cultural construct and has nothing to do with a person’s DNA. And the same for other social and cultural differences between the sexes.

Certainly many psychological differences between the sexes are influenced by karyotype - to the extent that karyotype influences hormones and that nature trumps nurture - and these psychological differences may explain why certain gender roles and gender expressions are the way they are - which is what I was explaining in that comment. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderWe separate bathrooms by sex because it is an area where we uncover our sex parts. — Harry Hindu

Which is why I said it makes sense to let trans women who have had bottom surgery use the women’s bathroom and trans men who have had bottom surgery use the men’s bathroom.

So which is it, is gender a social construct - a spectrum of societal expectations of the sexes, or is it a spectrum of various feelings an individual has? — Harry Hindu

It’s both, which is why the article on gender that I directed you to says “gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender.”

If gender is psychological then provide some examples that are clearly psychological (which would just mean that they are biological) instead of being clearly social/cultural - like wearing a dress and high heels is. — Harry Hindu

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_identity

It's your argument. You're the one that needs to support it, not me. — Harry Hindu

It’s not my argument. It’s what the experts in psychology and psychiatry have determined. If you think that they're wrong then the burden is on you to explain where they’ve gone wrong. I no more have to support their claims than I have to support the claims of biologists when trying to educate someone on evolution.

And this is the fundamental problem with your position. You seem to question the very existence of gender (as something distinct from biological sex) despite what the experts say and despite the existence of transgender people.

It's one thing to argue that sports teams, bathrooms, prisons, etc. ought be divided by biological sex regardless of gender identity – and as this is a political matter you're well within your rights to – but to deny that gender identity is even a thing strikes me as willful ignorance. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderYou're getting a little speculative there. — frank

Yep.

It’s interesting to consider how and why the social and cultural differences between men and women have developed over time. I suspect things were very different in the Paleolithic. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderI'm suggesting the possibility that the majority of the differences between sexes found in the article you linked are cultural, social, and otherwise "learned." — Outlander

It does say as much:

Sex differences in psychology are differences in the mental functions and behaviors of the sexes and are due to a complex interplay of biological, developmental, and cultural factors.

...

Such variation may be innate, learned, or both.

...

A number of factors combine to influence the development of sex differences, including genetics and epigenetics; differences in brain structure and function; hormones, and socialization.

...

Both biological and social/environmental factors have been studied for their impact on sex differences. Separating biological from environmental effects is difficult, and advocates for biological influences generally accept that social factors are also important.

So I suppose there's likely a sort of feedback loop across the centuries, with any initial social and cultural differences between the sexes stemming from "natural" psychological differences, and then these social and cultural differences being the cause of further "nurtured" psychological differences which in turn drive further social and cultural differences. -

Disambiguating the concept of genderAnd I am asking you how it logically follows that these distinctions qualify as sexual differences if they occur across both sexes. — Harry Hindu

Presumably because of their prevalence. If some trait is typical of 98% of biological men but only 2% of biological women then it’s an example of a sex difference, but you’re better off asking a psychologist, not me.

I’ve linked to the article, it has a list of references, so do the research if you’re unwilling to trust it at face value.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum