-

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBecause Frodo definitely isn't a physical object in spacetime. — frank

Again, you're equivocating.

When we talk about a fictional world in which there is gold but no people we are not talking about a fictional world in which there is imaginary gold but no people; we're talking about a fictional world in which there is actual, real, physical gold but no people.

Even if this fictional world is imaginary. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongIf World X is just a fiction, then it wouldn't be a set of physical objects in spacetime, would it? — frank

It's a fictional world in which planets and stars exist but people and propositions don't, just as the Lord of the Rings universe is a fictional world in which orcs exist but computers don't.

Like Banno you're equivocating. The fact that we use language and propositions to talk about a fictional world does not entail that there are languages and propositions in this fictional world.

A world without language is, by definition, a world without language and so a world without propositions.

If you want to claim that a world without propositions is incoherent/empty then you must claim that a world without language is incoherent/empty, but that's a strong form of anti-realism, and presumably not something that you (or Banno) are willing to endorse. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongSo what's the ontology of World X? Is it in another dimension? — frank

That depends on whether or not there is an (infinite) multiverse. If there is then there is likely some universe in which there is gold but no people playing chess or using language (and so no propositions). If there isn't then World X is just a fiction. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongDoesn't that mean World X is empty? A world is basically a set of propositions. — frank

No, a world can be a set of physical objects situated in spacetime.

As I said many pages and weeks ago, the existence of gold does not depend on the existence of the proposition "gold exists". -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongIn a world without wood, can there be no chess? — Banno

There might be something else that is used other than wood but so far you haven't offered any replacement for language that allows for propositions in that world.

At the moment your position is akin to saying that there is chess in a barren world, and I'm the one saying that there isn't – that there is chess in a world only if there are people (or computers) in that world playing chess.

It is clear that there are propositions, including those that set up the world in question. — Banno

We are using language and propositions to talk about that world, but there are no languages or propositions in that world.

You continue to equivocate.

Try reading the section on Truth in a World vs. Truth at a World again. As a very explicit example it offers:

A proposition like <there are no propositions> is true at certain possible worlds but true in none.

If "there are no propositions" is true at World X then there are no propositions in World X, just as if "there is no English language" is true at World X then there is no English language in World X. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere is a difference between an utterance and a proposition, hence there is a difference between a world in which there are no utterances and one in which there are no propositions. — Banno

And now you're back to contradicting what you said earlier when you said that propositions are constructed by us using words.

If propositions are constructed by language users using words then if there is no language use in a world then there are no propositions in that world.

You really can't make up your mind. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongYou want to say that there is no truth to there being gold in that world — Banno

No I don't.

I'm only saying what I am literally saying, which is that there is no language in that hypothetical world and so no propositions in that hypothetical world and so no true propositions (truths) in that hypothetical world.

I have repeatedly said that there is gold in that world.

If you are reading something into my words that isn't there then that's on you. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongSure, there is no English in that hypothetical world. But there is gold [in that hypothetical world]. — Banno

And I have never disagreed with this.

I have only ever claimed that because there is no language in that hypothetical world there are no propositions in that hypothetical world and so no true propositions (truths) in that hypothetical world.

The fact that we are using the English language and its propositions to truthfully talk about that hypothetical world is irrelevant. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongWhere in any of this are we not doing things with words? — Banno

We're asking about a hypothetical world in which there are no people doing things with words. This is where the distinction between "truth at" and "truth in" is important.

Obviously we are using the English language to describe this hypothetical world but then also obviously there is no English language in this hypothetical world. You seem unwilling to make this same distinction when discussing propositions and truth, as if somehow they're special entities very unlike the English language. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere are abstractions. These are constructed by us, doing things using words. — Banno

And this is where you're not making sense.

You say that propositions are constructed by us doing things using words but then say that there are true propositions even if we're not doing things using words. Make up your mind. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongI would say that platonism best reflects the way we generally think about things like the set of natural numbers N. — frank

That doesn't make it true. As I said earlier, it's us being uncritically bewitched by grammar into thinking that a sentence such are "there are numbers" is saying something it's not.

Instead of those, look at the SEP article on philosophy of math. It shows the alternatives to platonism are logicism, intuitionism, formalism, and predicativism.

Do you want to go through those? — frank

No, because it's not relevant to what I am arguing, which concerns whether or not there are mind-independent true propositions. Whether these propositions are about mathematics or physics makes no difference. To repeat what I said above:

Some linguistic activity by a suitably intelligent mind is required for there to be propositional content, and so for there to be a true proposition, and so for there to be a truth.

This is all I am arguing. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBut I think we should be careful in saying that "an utterance" is required. — J

I mentioned elsewhere that terms like "utterance" are being used as a catch-all for speech, writing, signing, believing, thinking, etc.

Some linguistic activity by a suitably intelligent mind is required for there to be propositional content, and so for there to be a true proposition, and so for there to be a truth. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong

You're referring to this argument?

(P1) We ought to have ontological commitment to all and only the entities that are indispensable to our best scientific theories.

(P2) Mathematical entities are indispensable to our best scientific theories.

(C) We ought to have ontological commitment to mathematical entities.

Firstly, "having ontological commitment to mathematical entities" does not entail platonism. Immanent realists and conceptualists also have ontological commitment to mathematical entities.

Secondly, P2 appears to presuppose that nominalism is false. The nominalist might agree that mathematics is indispensable to our scientific theories but won't agree that mathematical entities are indispensable to our best scientific theories, because they believe that no mathematical entities exist. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongwhich is that if you deny platonism of any kind, you're rejecting science in general — frank

You don't need to believe in mind-independent abstract objects to believe in mind-independent physical objects, and you don't need to believe in mind-independent abstract objects to believe that these mind-independent physical objects move and interact with one another. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong

It's not clear what you're asking.

Are you asking me if the sentence "we will say true things in the future" is true? -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongFYI, @bongo fury and @frank

Quine

Quine does not accept the existence of any abstract objects apart from sets. His ontology thus excludes other alleged abstracta, such as properties, propositions (as distinct from sentences), and merely possible entities. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong

So with paintings there is the landscape being painted and the painting. We say that the painting is accurate if it resembles the landscape being painted and inaccurate if it doesn't.

With language there is the landscape being described and the utterance. We say that the utterance is true if its propositional content "resembles" (for want of a better word) the landscape being described and false if it doesn't.

But according to platonists, in most situations there is the landscape being described, the propositional content, but no utterance, and that this propositional content is true if it "resembles" the landscape being described and false if it doesn't.

I don't think the notion that there is false propositional content without an utterance makes any sense, and so I also don't think the notion that there is true propositional content without an utterance makes any sense.

Even if we want to distinguish an utterance from its propositional content, an utterance is required for there to be propositional content. Propositional content, whether true or false, doesn't "exist" as some mind-independent abstract entity that somehow becomes the propositional content of a particular utterance.

So when you ask if the propositional content of an utterance was true before the utterance was made, I literally don't understand you. The propositional content only "came into being" when a meaningful utterance was uttered, which is just to say that we understand an utterance (e.g. conceptualism), and which is perhaps best explained by Wittgenstein. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongYou're basically saying Quine was an idiot. — frank

No, I'm saying he's wrong, just as every other conceptualist and immanent realist and nominalists says.

Surely Quine suggests we refer timelessly (non-modally) to the sentence inscribed or uttered in a future region of space-time? And we describe it (rightly by your hypothesis) as true? Is that non-sensical? — bongo fury

Yes. I think that Wittgenstein provides a much more sensible approach to language. There's no mystical connection between utterances and mind-independent, non-spatial, non-temportal abstract objects; there's just actual language-use and the resulting psychological and behavioural responses. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongI don't think you're bothering to look very deeply into this. — frank

I think I’m looking into it only as deeply as it needs to be. Platonism is a result of being bewitched by language, misinterpreting the grammar as entailing something it doesn’t. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBut are you denying that it's already true? — bongo fury

I’ve been over this so many times.

The word “it” in the phrase “is it true?” refers to either an utterance or an utterance-dependent proposition, and so asking if an utterance or proposition is true before it is uttered is a nonsensical question, like asking if a painting is accurate before it is painted. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongJust be aware of what you're giving up if you reject mathematical realism. — frank

I’d be giving up on mind-independent abstract objects, which is of no concern.

Just look at Quine's indispensability argument in the SEP article I cited. — frank

And perhaps you could look at the epistemological argument against platonism. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongI think immanent realism collapses into conceptualism — Michael

I'm not sure how. — frank

Because the immanent realist believes that "properties like redness exist only in the physical world, in particular, in actual red things."

An immanent realist about propositions would have to believe that propositions exist only in particular things, and presumably the only particular things within which a proposition can exist is an utterance. But a sound is only an utterance if there is a mind to interpret the sound as an utterance. And so it's not clear how immanent realism about propositions can be distinguished from conceptualism about propositions.

Hence it seems that with respect to propositions we must be platonists (mind-independent propositions), conceptualists (mind-dependent propositions), or nominalists (no propositions).

Only platonism allows for something that can putatively count as a mind-independent truth, and I think that platonism about propositions is more problematic than the alternatives, most likely because I think that physicalism or property dualism is more parsimonious than the theory that there is the physical, the mental, and the independently abstract. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBut you know they're all true. Even the unwritten ones. Since they satisfy the equation n+(n+1)=2n+1. — fdrake

Firstly, I don’t think that n+(n+1)=2n+1 proves mathematical platonism.

Secondly, what is true? The equation? What is an equation? Is it a meaningful string of symbols?

This is where I think the grammar is causing confusion. There is both a platonist and a non-platonist interpretation of "there are unwritten equations".

As an analogy, consider something like "there are unpainted red paintings". It's certainly true in the non-platonic sense that someone could paint a red painting that doesn't exist in the present, but it's not true in the platonic sense that there exists in the present some painting that is red but unpainted.

And so "there are unwritten true equations" is true in the non-platonic sense that someone could write a true equation that doesn't exist in the present, but it's not true in the platonic sense that there exists in the present some equation that is true but unwritten. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong

In general there are four different positions on the topic, paraphrased from here:

1. Platonism - there are mind-independent and particular-independent abstract objects

2. Immanent realism - there are mind-independent and particular-dependent abstract objects

3. Conceptualism - there are mind-dependent abstract objects

4. Nominalism - there are no abstract objects

With respect to propositions, I think immanent realism collapses into conceptualism (propositions are particular-dependent, i.e. dependent on meaningful utterances, and meaningful utterances are mind-dependent), giving us three options:

1. Propositions are mind-independent

2. Propositions are mind-dependent

3. There are no propositions

(1) and (2) will argue that truth is a property of propositions, (3) that truth is a property of utterances.

(1) allows for true propositions (truths) without minds, (2) and (3) only for true propositions (truths) with minds.

I reject platonism. I'm undecided on nominalism and conceptualism, but the things I am saying are consistent with both. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongAnd so the issue is forced into a juxtaposition. Better to ask how propositions are dependent on mind — Banno

Given that the crux of the recent debate is over whether or not there are truths (true propositions) without minds, it's an appropriate juxtaposition.

If there are truths without minds then propositions are mind-independent (platonism).

If propositions are mind-dependent (conceptualism) then there are no truths without minds. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere are infinite additions. — Banno

Are you arguing for mathematical platonism, or are you arguing for a non-platonic interpretation of "there are an infinite number of true additions and false additions that we could write out"?

Because I don't believe in mathematical platonism.

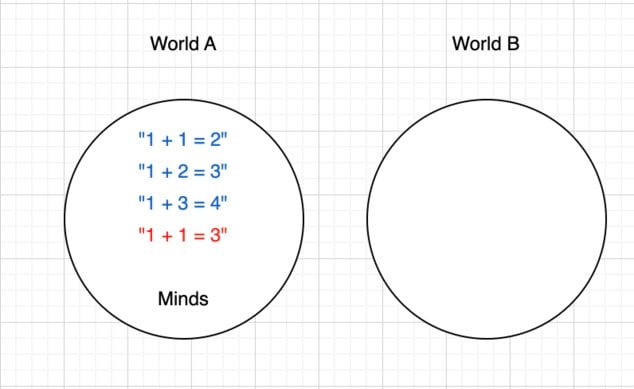

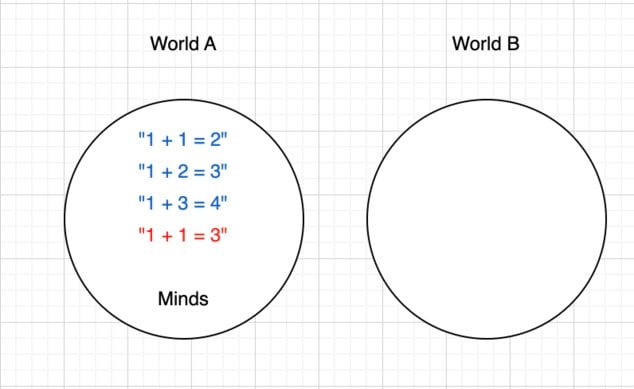

Returning back to my diagrams:

There are an infinite number of quoted mathematical equations that we could write out inside the World A circle, and in writing them out they are either blue (true) or red (false), but none that we can write out inside the World B circle because there's nobody in that world to assert them. Which is why there are mathematical truths and falsehoods in World A but no mathematical truths or falsehoods in World B.

This is where the platonist disagrees; he would argue that there are an infinite number of blue and red mathematical equations that we could write inside the World B circle even though there's nobody in that world to assert them.

So please clarify your position on this. Is it sensible to write out red and blue mathematical equations inside the World B circle? -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere are really two parts to this discussion.

The first concerns the dispute between platonism and conceptualism – are propositions mind-independent or not?

The second concerns the dispute between realism and anti-realism (as defined by Dummett) – is a proposition’s truth value verification-transcendent or not?

This leaves us with four possible positions:

Platonism + realism: there are mind-independent propositions with verification-transcendent truth conditions.

Conceptualism + realism: there are mind-dependent propositions with verification-transcendent truth-conditions.

Conceptualism + anti-realism: there are mind-dependent propositions with verification-immanent truth-conditions.

Platonism + anti-realism: there are mind-independent propositions with verification-immanent truth-conditions.

I’m not sure how sensible the last of these is, and so perhaps we can dismiss it for now.

Of the other three, only platonism + realism allows for anything that can be considered a “mind-independent truth”.

Now there is some ambiguity with the phrase “mind-independent truth”. On the one hand it might mean “a proposition that is mind-independent and true” and on the other hand it might mean “a proposition that is mind-independently true”.

The former is just platonism.

If the latter does not mean the former then it more accurately means “a proposition that is mind-dependent and mind-independently true”, which is conceptualism, and doesn’t really seem to satisfy the intention of the phrase “mind-independent truth”, and is why I have been arguing that either platonism is correct or there are no truths if there are no minds.

Note specifically that a proposition being mind-dependent does not entail that its truth value is mind-dependent, which I think is where @frank is making his mistake. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongBut you are saying it wrong. — Banno

I don't think I am.

Take "there are unuttered propositions" which I compared to "there are unborn babies".

That there are unborn babies just is that new babies will be born in the future, and so that there are unuttered propositions just is that new propositions will be uttered in the future, consistent with everything I have been saying.

That you think that "there are unuttered propositions" is inconsistent with my position suggests that you are being led astray by the grammar of this sentence into thinking it entails something else – something that seems akin to platonism even though you don't seem to want to commit to platonism, which is why it is not clear to me what you are trying to say, and why I think you're falling victim to an unintentional equivocation caused by the imprecise use of the terms "true" and "truth" that I am trying to fix. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongYou just slide the goal from utterances to propositions to assertion: — Banno

Yes, it makes no difference. Either way, platonism is wrong and truth- and falsehood-predication only makes sense when the object predicated as either true or false is a feature of language. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongYou are headed to absurdity, forced to conclude that the number of true additions is finite, since it is limited to only those that have been uttered. — Banno

I am saying that the number of true assertions that have been made is finite, that the number of false assertions that have been made is finite, that platonism is incorrect, and that using the adjectives "true" and "false" to describe something other than an assertion is either a category error or vacuous.

It ain't nonsense. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere are unuttered propositions. — Banno

Only in the trivial sense that there are unborn babies.

Srap showed this by uttering one. — Banno

That's a contradiction. You can't show that there are unuttered propositions by uttering a proposition. In uttering a proposition you only show that there's an uttered proposition.

The only alternative is for you to claim that 799168003115 + 193637359638 = 992805362753 was not true until Srap made it so by uttering it. — Banno

This is like saying "the only alternative is for you to claim that the painting was not accurate until the painter made it so by painting it". You're not making any sense.

I'm not saying that some sentence wasn't true before it was said, because any talk about a sentence before it is said is incoherent. I'm only saying that only the things we say are true or false. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongAnd yet ↪Srap Tasmaner showed you an example that negates your assertion. — Banno

No he didn't.

But utterances and propositions are not the very same. — Banno

I'm not saying that they're the very same. I'm saying that if there are no utterances then there are no propositions, i.e. that platonism is wrong. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongYou didn't address the argument, which is that different utterances are understood as saying the same thing; therefore what they say is not peculiar to an individual utterance. — Banno

I haven't claimed otherwise. I've only claimed that the only things that can be true or false are the things we say (which I'm using as a catch-all for speech, writing, signing, thinking, believing, etc.).

Whether you want to interpret "what we say" as referring to an utterance or a sentence or a proposition makes no difference; either way, we must be saying something for something to be true or for something to be false.

The claim that there are true and false sentences/propositions/predications even if nothing is being said is incoherent. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrong"1+1=3 is false" becasue by substitution 1+1≠ 3.

"1+1=3" is true ≡ 1+1=3. — Banno

I don't see how that answers my question. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongThere is a reason we have different words for utterance, sentence, statement, proposition, predication...

Which of these is true? Any of them. — Banno

Sure, but there are no sentences if there are no utterances, there are no statements if there are no utterances, there are no propositions if there are no utterances, and there are no predications if there are no utterances.

There is a red mountain (which isn't truth-apt) and there is the utterance "the mountain is red" (which is truth-apt). There isn't some third thing – the fact that the mountain is red (allegedly truth-apt) – distinct from the former and independent of the latter. Which is why I disagree with platonism. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongAnd moreover, it's not an error to say that the fact that 1 + 1 = 2 is true, it's just redundant. — Banno

And how does this work with the case of "1 + 1 = 3" being false? We certainly can't say that the fact that 1 + 1 = 3 is false. So if you want to say that "it" is false even if not uttered, what other than the sentence is the sort of thing that can be false?

As for redundancy, I addressed something like that several times. The claim that it is true that X can be interpreted in one of two ways:

1. "X" is true

2. X

And the claim that it is false that X can be interpreted in one of two ways:

1. "X" is false

2. not X

If we interpret it as (1) then we're predicating truth of a sentence. If we interpret it as (2) then the phrase "it is true that" is vacuous, with the words "it" and "true" not referring to any entity or any property, and nothing is added by using such grammar, but in using such grammar you risk equivocating. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongthe second order predication "There is gold in those hills" is true, even if never uttered. — Banno

This second order predication is still a sentence that you have written and have described using the adjective "true", and asserting that it is true even if never uttered is like asserting that a painting is accurate even if never painted. It simply makes no sense. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongWhat are the chances that anyone has ever said that 799168003115 + 193637359638 = 992805362753? — Srap Tasmaner

Well you've just said it now?

Are you perhaps suggesting that it was true before you said it? What does the word "it" here refer to? Does it refer to the sentence "799168003115 + 193637359638 = 992805362753"? Then we're back to what I said above; saying that a sentence is true before it is said makes as little sense as saying that a painting is accurate before it is painted.

Perhaps the word "it" refers to the fact that 799168003115 + 193637359638 = 992805362753? I don't think that facts are the sort of thing that can be true or false, i.e. it's a category error to say that the fact that 1 + 1 = 2 is true. And what if I were to assert the false sentence "1 + 1 = 3"? Was it false before I said it? But the word "it" here can't refer to the fact that 1 + 1 = 3 because 1 + 1 does not equal 3. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongIt is. A truth realist believes there are truths which have never been uttered. — frank

A platonist does, but I don't think that a realist must be a platonist. A realist can be a non-platonist by accepting that only the things we say are true or false but that some of the things we say are unknowably true or false. -

Is the distinction between metaphysical realism & anti realism useless and/or wrongyou don't think P is true until someone expresses P. — frank

I also don't think that a painting is accurate until someone has painted it. But that's because a painting being accurate (or inaccurate) before it is painted makes no sense. Just as a sentence being true (or false) before it is said makes no sense.

This isn't truth skepticism.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum