-

Moliere

6.5k@Leontiskos Then we've likely been talking past and working out and all the rest that we do here.

Moliere

6.5k@Leontiskos Then we've likely been talking past and working out and all the rest that we do here.

There is a possibility that I think isn't taken seriously enough that marks a difference between how I'm thinking on "What is real?" and how it seems Leon is.

And I think this would include our conversation too @Count Timothy von Icarus

There's the sense in which, if pressed, I'll say that I think the water which we drink today is H2O, and that the water which Aristotle refers to has at least a similar enough reference for comparison, if not the same meaning.

But this is a best guess, and not a philosophical demonstration.

Something that's operating in the background of my thoughts that hasn't been clear is the reason and use for historical examples, such as using Aristotle to talk about essentialism when a modern essentialist would not make the claims Aristotle did about water in marking out its essence. The reason I use Aristotle is because he is likely talking about the same thing, and yet he gets a different meaning. Further, his view was taken as the truth for a long time, and then it wasn't (and now it is, by some! :D) -- so there's a tangible conversation through history that we can reference in thinking through how the terms were developed. There's a tradition in which the terms meanings can come to make sense and we can make comparisons between the meanings of the terms. Further, when we accept meaning we get rid of the need for being as a kind of "ground" or "explanation" for why we're saying the things in the first place -- the historical method is what keeps the arguments from devolving into circularity and arbitrary stipulation.

Enough on meta-philosophical method -- I just wanted to make it clear why I've been using Aristotle and the rest rather than laying out propositions and definitions within logical form. And the reflection on the changing of meanings over time leads into the point I wanted to make in noting how the best guess is not a philosophical demonstration: when I look at how meaning has changed over time, and I presume that the thing referred to has not changed, and the meanings contradict, then it seems that either the thing has both meanings, contradictory though they be, or we invent meanings to make sense of the thing. Supposing the LNC holds in a metaphysically possible way, to use 's nesting of possibilities, and we change meanings then which meaning should be the one which is "true", and when will it be true? If we were wrong before then it's possible for us to be wrong again. And science cannot get us out of this conundrum because it is finite -- it deals with the "real' world, we'll say, so as to avoid poisoning the well in favor of physicalism, and the patterns we assign today can be seen as superseded tomorrow because of that. All scientific theories, no matter how certain we can come to see them as, are subject to change and subsumption by future discoveries, future subsumptions and corrections. Then, perhaps, water isn't really H2O, though the locals saw it that way, but from way up here we see....

This all by way of pointing out why I'm going over various meanings of "Water" through thinking on the question about "What is real?" -- let's say we have three contenders for what is real about water. @Banno's is that, in a particular example, we find out that the water was an oasis and not a mirage. In Kripke we find that if water is H2O, then water is necessarily H2O: there is no possible world in which water could be something else, without going into the metaphysics of what water is -- perhaps, to use the diagram again, "What is water?" is a question that can only be sensibly answered in the "Real Possible World" rather than the "Metaphysically possible world" (And, for what it's worth, even if it happens to be wrong, I couldn't make sense of Kripke without thinking of possible worlds as plausible worlds; i.e. what would I assent to as a genuine possibility in such-and-such a circumstance, and what objections might hold?)

For myself it seems that if we accept a realist metaphysics, and our meanings change, then we have to accept the very real possibility that most of what we know is false -- that it's "good enough" to begin with setting out a problem or understanding something, but the particular circumstance is where we'll find the thing rather than in the definition of what makes the thing what the thing is. This supposing the world does not change -- if the world changes, we could still accept a realist metaphysic, and this would make a great deal of sense out of why what seems simple is what smart people disagree about.

But then that just seems to stretch credibility too.

In both cases I'm sort of just setting out what makes reality what it is in relation to meaning -- the question to me is very much on the epistemic side, as I said. In a way what I'd pose is "What does this change in the meaning of water, something which actually seems quite mundane to us without much further ado, indicate about how we decide what is real?" -

J

2.4kI'm assuming there is some misunderstanding here — Count Timothy von Icarus

J

2.4kI'm assuming there is some misunderstanding here — Count Timothy von Icarus

Sure. I wonder whether you'd be willing to look back over my post and notice the different uses of "relativism" and "pluralism," and the ways in which I tried not to make blanket assertions about things like "the whole of logic, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and the philosophy of nature."

Just as a for-instance:

to the question of where relativism applies you say that this itself is subject to relativism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think you'd see, rereading, that this isn't accurate. Here's the exchange:

Is "which truths are pluralistic, context-dependent truths?" a question for which the answers are themselves "pluralistic, context-dependent truths?"

— Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, generally. — J -

Leontiskos

5.6keither the thing has both meanings — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6keither the thing has both meanings — Moliere

I would say that things don't have inherent meanings (at least for philosophy). I think you are still conflating metaphysics with linguistics. Throughout this post you talk a lot about "meanings," but essentialism is not about what words mean, it is about what things are.

1. The essentialist would be likely to say that water is H2O (or that water is always H2O).

1a. The essentialist would say that the term “water” signified H2O before 19th century chemistry. — Leontiskos

In (1) the essentialist is talking about a thing, water. In (1a) the essentialist is talking about a sign, "water." You are still talking about the meaning of signs, such as "water," at different times throughout history.

Neither Aristotle nor Kripke are merely talking about what a word-sign means.

For myself it seems that if we accept a realist metaphysics, and our meanings change, then we have to accept the very real possibility that most of what we know is false — Moliere

I've already pointed out that Lavoisier's discovery did not necessarily falsify what came before:

↪Moliere - Okay, great. And for Aristotelian essentialism this is taken for granted, namely that we can know water without knowing water fully, and that therefore future generations can improve on our understanding of water. None of that invalidates Aristotelian essentialism. It's actually baked in - crucially important for Aristotle who was emphatic in affirming the possibility of knowledge-growth.

This means that Lavoisier can learn something about water, in the sense that he learns something that was true, is true, and will be true about the substance water. His contribution does not need to entail that previous scientists were talking about something that was not H2O, and the previous scientists generally understood that they did not understand everything about water. — Leontiskos

When Lavoisier talks about water he is talking about a thing, not a word-sign. He is interested in the reality of water itself. -

Moliere

6.5kI would say that things don't have inherent meanings (at least for philosophy). I think you are still conflating metaphysics with linguistics. Throughout this post you talk a lot about "meanings," but essentialism is not about what words mean, it is about what things are. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kI would say that things don't have inherent meanings (at least for philosophy). I think you are still conflating metaphysics with linguistics. Throughout this post you talk a lot about "meanings," but essentialism is not about what words mean, it is about what things are. — Leontiskos

In order to talk about what is real we need to know what it is we mean by "What is real?" -- this would be before any question on essentialism. In order to talk about what water is we have to be able to talk about "What does it mean when we say "Water is real", or "Water has an essence"? or "The essence of water is that it is H2O"?"

We can't really deal with any dead philosopher without dealing with meanings -- the words have to mean something, rather than be the thing they are about.

I've already pointed out that Lavoisier's discovery did not necessarily falsify what came before: — Leontiskos

Whether they falsify one another or not is different from whether they mean the same thing. I don't think they do, but are probably talking about the same thing in nature. I do, however, think you have to pick one or the other if we presume that Lavoisier and Aristotle are talking about the same thing because the meanings are not the same. The lack of falsification is because the meanings are disparate and they aren't in conversation with one another, and they aren't even doing the same thing.

It's the difference in meaning that raises the question -- if the thing is the same why does the meaning differ? If stating "What the thing is" in a metaphysical way can be done without knowing what it is we mean by claims on reality then maybe you'd have a point. But I don't think we can just begin with the things as they are in the abstract -- we begin with things as they are around us. -

Leontiskos

5.6kIn order to talk about what is real we need to know what it is we mean by "What is real?" -- this would be before any question on essentialism. In order to talk about what water is we have to be able to talk about "What does it mean when we say "Water is real", or "Water has an essence"? or "The essence of water is that it is H2O"?" — Moliere

Leontiskos

5.6kIn order to talk about what is real we need to know what it is we mean by "What is real?" -- this would be before any question on essentialism. In order to talk about what water is we have to be able to talk about "What does it mean when we say "Water is real", or "Water has an essence"? or "The essence of water is that it is H2O"?" — Moliere

Yes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water." Familiarity with water is a precondition for familiarity with the English sign "water."

We can't really deal with any dead philosopher without dealing with meanings -- the words have to mean something, rather than be the thing they are about. — Moliere

I think the key here is that when Lavoisier says, "Water is H2O," he could be saying two different things:

M: "Water is H2O, and if anyone, past or future, says anything else about water, they are wrong."

N: "Water is H2O, and there are all sorts of other true things that can be said about water."

You seem to take Aristotle to have said something like (M), but that's not generally what a scientist means when they say, "Water is such-and-such." If all scientists are saying things like (M) then there can be no growth in knowledge and therefore Aristotle's approach is wrong. But given that scientists are usually saying things like ( N) there is no true barrier to growth in knowledge - either individually or communally.

Whether they falsify one another or not is different from whether they mean the same thing. I don't think they do, but are probably talking about the same thing in nature. I do, however, think you have to pick one or the other if we presume that Lavoisier and Aristotle are talking about the same thing because the meanings are not the same. The lack of falsification is because the meanings are disparate and they aren't in conversation with one another, and they aren't even doing the same thing. — Moliere

Much of this is right, but again, the crucial point you are failing to recognize is that neither Aristotle nor Lavoisier mean that anyone who does not mean what they mean must therefore be wrong. That is a very strange reading. No one is claiming to have a complete and exclusive understanding of water.

It's the difference in meaning that raises the question -- if the thing is the same why does the meaning differ? — Moliere

Because learning occurred and knowledge grew. Lavoisier knows more about water than Aristotle did. Aristotle would expect this to be the case for later scientists. -

Tom Storm

10.8kAnd these are true measures of usefulness, or only "useful" measures for usefulness? The problem is that this seems to head towards an infinite regress. Something is "useful" according to some "pragmatic metric," which is itself only a "good metric" for determining "usefulness" according to some other pragmatically selected metric. It has to stop somewhere, generally in power, popularity contests, tradition, or sheer "IDK, I just prefer it." — Count Timothy von Icarus

Tom Storm

10.8kAnd these are true measures of usefulness, or only "useful" measures for usefulness? The problem is that this seems to head towards an infinite regress. Something is "useful" according to some "pragmatic metric," which is itself only a "good metric" for determining "usefulness" according to some other pragmatically selected metric. It has to stop somewhere, generally in power, popularity contests, tradition, or sheer "IDK, I just prefer it." — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, this is a familiar criticism, and the usual response is that infinite regress is probably unavoidable since we don’t have any ultimate grounding. There is no non-circular grounding for us to cling to, try as we might. We settle, at least for a while, on what works, and over time this changes. In that sense, our version of reality or truth functions similarly to how language works; it doesn’t have a grounding outside of our shared conventions and practices.

Bear in mind that I am sympathetic to these views, but I hold them tentatively.

what we can point to is broad agreement,

So popularity makes something true? Truth is like democracy?

shared standards

Tradition makes something true?

and better or worse outcomes within a community or set of practices.

Better or worse according to who? Truly better or worse?

I hope you can see why I don't think this gets us past "everything is politics and power relations." I think Nietzsche was spot on as a diagnostician for where this sort of thing heads. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Not quite. The position isn’t that truth is mere popularity, but that truth is built through ongoing conversation and agreement. What counts as true is what survives criticism, investigation, and revision within a community over time. So instead of certainty, we have a fallible and evolving consensus. Tradition, in such a context, is something that should be investigated and revised if necessary.

Humans work to create better ways to live together, but these are contingent matters. It’s still meaningful, it just isn’t definitive, permanent, or grounded in some ultimate truth. This doesn’t inevitably reduce everything to power and politics; as Rorty might argue, it can also lead us toward solidarity. The lack of a foundation doesn’t prevent us from having conversations about improvement, you might even say it invites them.

It also seems to me that even if you believe in foundationalism or some transcendent notion of the Good, there is still no universal agreement about what it actually is. So, in practice, we’re all engaged in an act of creative invention and ongoing conversation. I think everyone is in the same boat. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I think you'd see, rereading, that this isn't accurate.

How so? I'm genuinely confused here? What exactly would be your explanation of why relativism and pluralism re truth is wrong?

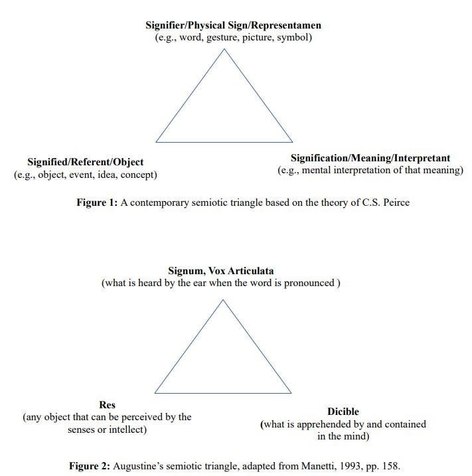

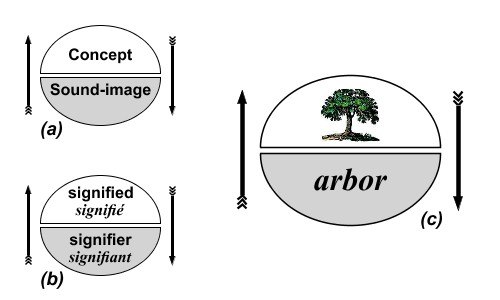

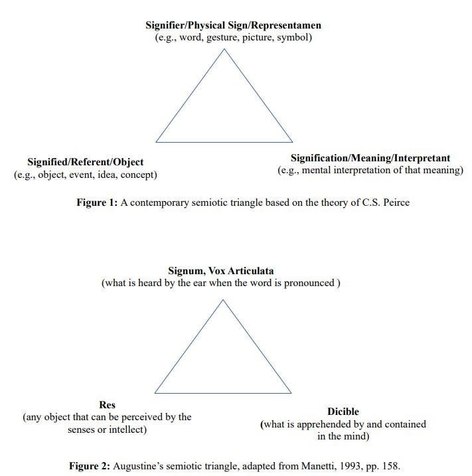

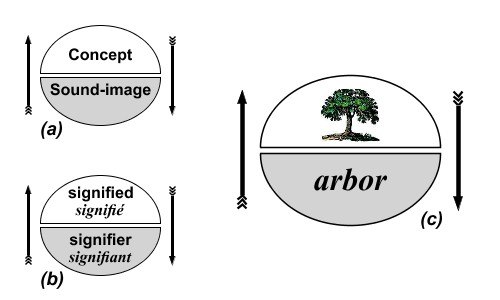

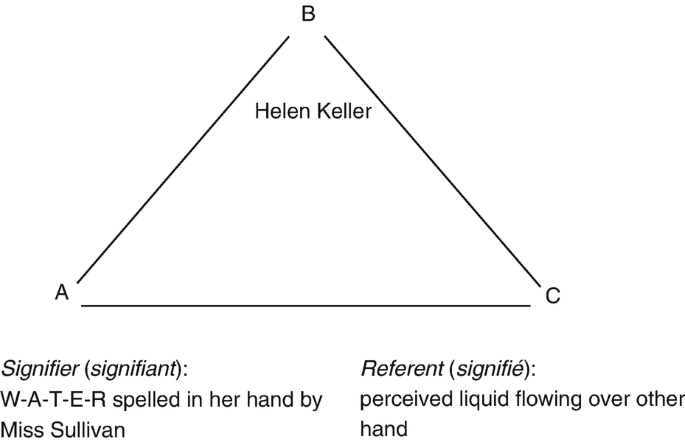

A thorny issue. I suppose one's understanding of signs is important here, as well as the proper ordering of the sciences/philosophy (if one is supposed at all).

If metaphysics has priority, we can say that water has to be before it is known. The being, its actuality, is called in to explain the sign and evolutions in what the sign evokes

But the role of the object is collapsed with that of the interpretant in the Sausserean model that has so much influence on post-structuralism, and that paints a different picture.

And the difference between these two models lies in the question: in the second model, what is signified: the object, or an interpretation called forth by the sign (the meaning)? That seems to be the essence of the question here to me.

It would be question begging to simply assume the prior model of course, but I think one can argue to it on a number of grounds.

First, a system of signs that only ever refers to other signs would seem to be, in information theoretic terms, about nothing but those signs. This would be the idea, rarely explicitly endorsed, but sometimes implied, that books about botany aren't about plants, but are rather about words, pictures, and models, or that one primarily learns about models, mathematics, and words when one studies physics. There is also the question of the phenomenological content associated with signs. Where would that come from?

Second is the old question: "why these signs (with their content)?" This is the old question of quiddity that Aristotle is primarily interested in. Then also, "since these appear to be contingent, why do these signs exist at all?" (the expanded question of Avicenna and Aquinas). Which is, to my mind, a question of how potential is made actual.

Yes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water."

I agree as a rule, although the tricky thing is that one might indeed become familiar with something first through signs that refer to some other thing. We can learn about things through references to what is similar, including through abstract references. Likewise, we can compose, divide, and concatenate from past experience and share this with others so that what we are talking about refers to no prior extra-mental actuality (at least not in any direct sense).

But this cannot be the case for everything, else it would seem that our words would have no content. Our speech would be a sort of empty rule following, akin to the Chinese Room.

Mary the Color Scientist can know so much about color because she has been exposed to the rest of the world, just sans color. But if she had no experiences at all, it's hard to see how she could "know" much of anything.

Now I suppose this doesn't require some prior actuality behind sense experience and signs. They could move themselves. It's just that if they did move themselves there wouldn't be any explanation for why they do so one way and not any other. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

In that sense, our version of reality or truth functions similarly to how language works; it doesn’t have a grounding outside of our shared conventions and practices.

I guess I probably wouldn't agree with the ideas behind this, so that might be a difference.

The position isn’t that truth is mere popularity, but that truth is built through ongoing conversation and agreement. What counts as true is what survives criticism, investigation, and revision within a community over time. So instead of certainty, we have a fallible and evolving consensus. Tradition, in such a context, is something that should be investigated and revised if necessary.

Right, I have no problems with fallibilism and a circular epistemology. A certain sort of fallibilism seems necessary to defuse the idea that one most know everything to know anything.

But I also don't think it's helpful to conflate a rejection of relativism with a positive assertion of foundationalism and infallibilism, which I seem to recall Rorty doing at times. Precisely because one need not know everything to know anything, it does not seem necessary to have an "ultimate" or "One True" in sight to make judgements. Rorty sounds sensible to me sometimes, but then there is stuff like the idea that a skrewdriver itself, its properties, recommends nothing to us about its use, that strike me as obviously wrong.

Anyhow, those all seem to me like points related to fallibilism and foundationalism. But with

Humans work to create better ways to live together,

We settle, at least for a while, on what works

having conversations about improvement,

In a relativism based on anti-realism (which I'm aware no one in this thread has suggested) there is simply no fact of the matter about these criteria you've mentioned. Nothing "works better" than anything else. So, we can debate in terms of "what works," or "is good," but, per the old emotivist maxim, "this is good" just means "hoorah for this!" That seems to me to still reduce to power relations.

In a relativism where truth about "what works" and "better" changes with social context (where there is no human telos), where "we decide" (as individuals or as a community), none of those claims about "what works" or "what constitutes improvement" is grounded in any sort of underlying "goodness" or "working" that is separate from current belief and desire. That is, there is nothing outside the "playing field" of power politics. Rather, if something "truly works" or is "truly good," depends on what people are driven towards at the moment.

This certainly still seems to me to be very open to a reduction towards power. Truth as "justification within a society," for instance, seems obviously open to becoming a power struggle. One can just look at real life examples from totalitarian societies or a limit case in fiction like 1984 and "A Brave New World." "A Brave New World" is probably the more difficult case because it's obviously a case with a tremendous amount of manipulation, yet one where people are positively inclined towards the system, and even their own manipulation.

Now, I am all for the idea that the human good is always filtered through some particular culture or historical moment, and that this will change its general "shape." It's the denial of any prior form to this good that I think sets up the devolution into power politics. Likewise, human knowledge is always filtered through a particular culture and historical moment. Yet there are things that are prior to any culture or historical moment, and which thus determine the shape of human knowledge in all cultures and historical moments. The being of an ant or tiger for instance, is prior to culture, as its own organic whole, and so there is a truth to it that is filtered through culture, but not dependent upon it.

Edit: the other thing with him (and a lot of other relativistic arguments) is the heavy reliance on debunking. But debunking only works if we have a true dichotomy such that showing ~A is equivalent with showing B. I guess to the early topic of skeptical and straight solutions, it seems to me like a lot of skeptical solutions likewise rely on debunking heavily. -

Banno

30.6kLet's emphasis what is being argued. It's is not that there cannot be one monolithic Explanation of Everything, one explanation that encompass in a consistent binary logic everything we know from physics and biology through to love and relationships.

Banno

30.6kLet's emphasis what is being argued. It's is not that there cannot be one monolithic Explanation of Everything, one explanation that encompass in a consistent binary logic everything we know from physics and biology through to love and relationships.

We might be able to produce such a system. But we do not have such a system now. Nothing like it. And there are reasons to think it pretty unlikely that knowledge could be presented in this way without loosing quite a bit.

What is being argued is the lesser point, that we might do well not to assume that there is such an Explanation of Everything, even if we don't know what it is.

This seemed to go missing in our earlier discussion, Tim, about Logical Nihilism.

FIrst, some comments on a few specific points.

Here the principle of noncontradiction is being used as a wedge. But making use of non-contradiction is already presuming one logical system over others. Non-contradiction does not apply, or is used quite differently, in paraconsistent logic, relevance logic, intuitionistic logic and quantum logic, for starters. Perhps your argument holds, and if we presume PNC then there must be One True Explanation Of Everything (the caps are indicative of a proper name - that this is an individual). But to presume only classical logic is to beg the question. It is to presume what is being doubted. As is the shallow response seen before - I thin form Leon rather than you - that these are not real logics; it presumes what is at questions - that there is only one real logic.So if "One Truth" (I guess I will start capitalizing it too) is "unhelpful," does that mean we affirm mutually contradictory truths based on what is "useful" at the time? — Count Timothy von Icarus

The very existence of these non-classical systems shows that rational discourse can persist without universal adherence to PNC.

A better point is your "Orwellian Nightmare":

Quite so. And this is an excellent reason to keep a close eye on those power relations, and to foster the sort of society in which "might makes right" is counterbalanced by other voices, by compassion, humility, and fallibilism. You know, those basic liberal virtues. How much worse would a world be in which only the One True Explanation Of Everything was acceptable, uncriticised?As I mentioned earlier, a difficulty with social "usefulness" being the ground of truth is that usefulness is itself shaped by current power relations. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Pluralists can accept many truths within different practices - physics, literature, religion, without affirming logical contradictions. But this doesn’t mean that "2+2=5" and "2+2=4" are both true. Pluralism has limits, governed by coherence, utility, and discursive standards.

I think this a much more wholesome response than supposing that some amongst us have access to the One True Explanation and the One True Logic.

seems to be thinking along similar lines. Thanks, Tom. I wonder who else agrees? -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Sometimes it is better to go with a clear stipulation than to muddle around in ambiguity.Yes, that the one sentence explanation of essences you've offered is metaphysically insubstantial — Count Timothy von Icarus

If what you mean by "one sentence explanation of essences you've offered is metaphysically insubstantial" is that it doesn't lead to the confusion of forms or triviality of what makes it what it is, then I will take that as an advantage to the stipulation.

And it doesn't presume nominalism.

You're not keen on taking up any of the seven counterpoints I made? Good, that'll save time. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Not likely.I imagine you’re unlikely to be a Rorty fan — Tom Storm

I rather think his influence will outweigh your heart beat.I like my chances against Rorty since I still have a heart beat — Count Timothy von Icarus

Weighing in on "But there are either facts about what is "truly more useful" or there aren't" is a good move. I was going to point out that this again presumes a merely binary logic, but your response covers that. -

Tom Storm

10.8k↪Tom Storm seems to be thinking along similar lines. Thanks, Tom. I wonder who else agrees? — Banno

Tom Storm

10.8k↪Tom Storm seems to be thinking along similar lines. Thanks, Tom. I wonder who else agrees? — Banno

I come to this largely from outside philosophy, with unsystematic reading and a lot of quiet festering, so naturally I would assume my ideas are probably not fully coherent.

I guess I probably wouldn't agree with the ideas behind this, so that might be a difference. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Indeed. And that's what this site is all about, civil disagreement. Hey, and I might be 'wrong'. Or you.

I think if one believes that the buck stops somewhere definative - god, the transcendental - then my view would seem messy and unsatisfying.

In a relativism based on anti-realism (which I'm aware no one in this thread has suggested) there is simply no fact of the matter about these criteria you've mentioned. Nothing "works better" than anything else. So, we can debate in terms of "what works," or "is good," but, per the old emotivist maxim, "this is good" just means "hoorah for this!" That seems to me to still reduce to power relations. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm not convinced this the right take, but I agree for many it's unsatisifying.

When someone says “this is good,” it doesn’t merely mean “hoorah for this” as a purely subjective exhortation, but rather that the community endorses this judgment because it coheres with shared experiences and serves as a reliable guide in practice. When you think about it, history is full of such social practices that have eventually been accepted then superseded, often abandoned, and sometimes even regretted. My view would be that we fumble in the darkness, trying to find ways of coping together, and since most humans seek to avoid suffering, certain patterns emerge in our practices.

Are power relations involved in this? Yes, and even power relations are contingent and unfixed. They are woven into most discussions about what is real and how we should live. I think Banno is right:

And this is an excellent reason to keep a close eye on those power relations, and to foster the sort of society in which "might makes right" is counterbalanced by other voices, by compassion, humility, and fallibilism. — Banno

Maybe this is inadequate, let me know. Sometimes I think that all of this resembles the functioning of road rules. They are somewhat arbitrary, but they work if applied consistently and are understood by the community of road users. They change over time, as situations change. They are an ongoing conversation. We seek to avoid accidents and death and aim to get to places efficiently and the road rules facilitate this, but none of this means the road rules have a transcendent origin. Nor can they be explained away as subjective and therefore lacking in a comprehensive utility. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6kYeah. But perhaps what we can agree on is that there are ambiguities in asking "what if water had none of the characteristics it actually has?" that need ironing out in order to understand what is being asked.

Yep. That's what I'm after.Maybe the right way to say it is, There is no Truly True answer to the question of what is Really Real! — J -

Banno

30.6kSometimes I think that all of this resembles the functioning of road rules. They are somewhat arbitrary, but they work if applied consistently and are understood by the community of road users. They change over time, as situations change. They are an ongoing conversation. We seek to avoid accidents and death and aim to get to places efficiently and the road rules facilitate this, but none of this means the road rules have a transcendent origin. Nor can they be explained away as subjective and therefore lacking in utility. — Tom Storm

Banno

30.6kSometimes I think that all of this resembles the functioning of road rules. They are somewhat arbitrary, but they work if applied consistently and are understood by the community of road users. They change over time, as situations change. They are an ongoing conversation. We seek to avoid accidents and death and aim to get to places efficiently and the road rules facilitate this, but none of this means the road rules have a transcendent origin. Nor can they be explained away as subjective and therefore lacking in utility. — Tom Storm

Think I'll steal that analogy.

It's not a stone tablet, it's a conversation. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

You know, those basic liberal virtues. How much worse would a world be in which only the One True Explanation Of Everything was acceptable, uncriticised?

I assume the unstated premises here are that the "One True Explanation of Everything" isn't really true and is only not criticized out of force, otherwise, it sounds like a world that would be immeasurably better—a world free from error and ignorance and in harmony.

I mean, what's the assumption here otherwise, that there would be a One True Explanation that was demonstrably true, and yet it would be bad if people didn't criticize it and demand error over truth and the worse over the better? (The old elevation of potency as "freedom" I suppose).

Pluralists can accept many truths within different practices - physics, literature, religion, without affirming logical contradictions. But this doesn’t mean that "2+2=5" and "2+2=4" are both true. Pluralism has limits, governed by coherence, utility, and discursive standards.

I think this a much more wholesome response than supposing that some amongst us have access to the One True Explanation and the One True Logic.

Yes, it's the bolded that seems to lead to the problems described here. You keep setting infallibilism and "absolute knowledge" up in a dichotomy with a pluralism based on utility, but this is a false dichotomy. Most fallibilists are not relativists. All that is required is a faith in reason (i.e. not misology) not "knowing everything."

From the thread:

Misology is not best expressed in the radical skeptic, who questions the ability of reason to comprehend or explain anything. For in throwing up their arguments against reason they grant it an explicit sort of authority. Rather, misology is best exhibited in the demotion of reason to a lower sort of "tool," one that must be used with other, higher goals/metrics in mind. The radical skeptic leaves reason alone, abandons it. According to Schindler, the misolog "ruins reason."

If we return to our caricatures we will find that neither seems to fully reject reason. The fundamentalist will make use of modern medical treatments and accept medical explanations, except where they have decided that dogma must trump reason. Likewise, our radical student might be more than happy to invoke statistics and reasoned argument in positioning their opposition to some right wing effort curb social welfare spending.

Where reason cannot be trusted, where dogma, or rather power relations or pragmatism must reign over it, is determined by needs, desires, aesthetic sentiment, etc. A good argument is good justification for belief/action... except when it isn't, when it can be dismissed on non-rational grounds.In this way, identity, power, etc. can come to trump argument. What decides when reason can be dismissed? In misology, it certainly isn't reason itself.

-

Banno

30.6kI think the reason Analytic philosophy likes "possible worlds" is because its reified formalism is logically manipulable in a very straightforward way. — Leontiskos

Banno

30.6kI think the reason Analytic philosophy likes "possible worlds" is because its reified formalism is logically manipulable in a very straightforward way. — Leontiskos

Trouble with this is that the folk you and Tim are are fond of citing are making use of formal modal logic and possible world semantics. Please understand that possible world semantics is wha shows that the formalisations are consistent. If your academic friends did not make use of the formal systems, their work would have very little standing in the community of philosophers.

You and Tim objecting to formal modal logic robs you both of the opportunity to present your arguments clearly.

The suggestion that formal logic is restricted to analytic philosophy is demonstrably ridiculous. Moreover, the people you cite make use of analytic techniques. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Here's the thing. Supose I come across the One True Explanation of Everything, and I convince everyone else that I'm right - after all, if it is the One True Explanation of Everything, I am right.I assume the unstated premises here are that the "One True Explanation of Everything" isn't really true and is only not criticized out of force, otherwise, it sounds like a world that would be immeasurably better—a world free from error and ignorance and in harmony. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But supose also that you think we are wrong.

What should I do? Is it OK for us to just shoot you, in order to eliminate dissent? Should we do what the One True Explanation of Everything demands, even if that leads to abomination?

Or should we adopt a bit of humility, and perhaps entertain the possibility that we might be mistaken?

Authoritarianism or Liberalism?

Funny, how here we are now moving over to the ideas entertained in the thread on Faith. I wonder why. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

You and Tim objecting to formal modal logic robs you both of the opportunity to present your arguments clearly.

I objected to the weak modal formulation of essences, that's hardly the same thing. But yes, there are also other ways to conceive of modality as well. For someone who argues that formalisms are merely tools selected for based on usefulness, you sure do like to appeal to them a lot as sources of authority and arbiters of metaphysics a lot though.

What was "Banno 's Principle? "It is easier to disagree with something if you start out by misunderstanding it." A bit rich coming from someone who frequently wants to post about "Aristotelian essence" and "Aristotelian logic," but seems to be unwilling to read about the basics of either.

The suggestion that formal logic is restricted to analytic philosophy is demonstrably ridiculous

:roll:

What should I do? Is it OK for me to just shoot you, in order to eliminate dissent? Should I do what the One True Explanation of Everything demands, even if that leads to abomination?

:roll:

Slow down, you're going to run out of straw over there. I suppose if you think that "the truly best way to do things" involves shooting dissenters that says more about you.

Funny, how here we are now moving over to the ideas entertained in the thread on Faith. I wonder why.

Hey, we made it 15 pages before the "Banno starts bringing up the religion of everyone who disagrees with him" bigotry phase of the thread. I'd say that's pretty good. -

Banno

30.6kFor someone who argues that formalisms are merely tools selected for based on usefulness, you sure do like to appeal to them a lot as sources of authority and arbiters of metaphysics a lot though. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Banno

30.6kFor someone who argues that formalisms are merely tools selected for based on usefulness, you sure do like to appeal to them a lot as sources of authority and arbiters of metaphysics a lot though. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, they are very good tools. And used not so much for authority as clarity and coherence.

I stand by that, and the rest, even if you pull funny faces at me.The suggestion that formal logic is restricted to analytic philosophy is demonstrably ridiculous

Please, fell free to address my arguments, when you have time. -

Banno

30.6kI'll take this a step further and say that at least arguably, supposing that analytic methods are exclusive to Analytic philosophy is to misunderstand the state of philosophy today. Analytic methods haven’t disappeared—they’ve become ubiquitous. Their success in clarifying argument, uncovering presuppositions, and enforcing rigor made them so effective that even their critics adopted them. The real consequence is not that philosophy is split into Analytic and non-Analytic camps, but that the distinction itself has lost relevance. What matters now is not whether someone is ‘Analytic’ but whether they’re philosophically serious—and that seriousness nearly always involves some analytic rigor.

Banno

30.6kI'll take this a step further and say that at least arguably, supposing that analytic methods are exclusive to Analytic philosophy is to misunderstand the state of philosophy today. Analytic methods haven’t disappeared—they’ve become ubiquitous. Their success in clarifying argument, uncovering presuppositions, and enforcing rigor made them so effective that even their critics adopted them. The real consequence is not that philosophy is split into Analytic and non-Analytic camps, but that the distinction itself has lost relevance. What matters now is not whether someone is ‘Analytic’ but whether they’re philosophically serious—and that seriousness nearly always involves some analytic rigor. -

Richard B

569

Richard B

569

Not sure what you are getting at, but I think a summary of what John Searle is doing in Intentionality may help to develop some understanding.

In the Introduction, Searle states, "One of the objectives is to provide a foundation for my two earlier books, Speech Acts, and Expression and Meaning, as well as for future investigations of these topics. A basic assumption behind my approach to problems of language is that the philosophy of language is a branch of the philosophy of mind. The capacity of speech acts to represent objects and states of affairs in the world is an extensions of the more biologically fundamental capacities of the mind (or brain) to relate the organism to the world by way such mental states as belief and desire, and especially through action and perception. Since speech acts are a type of human action, and since the capacity of speech to represent objects and states of affairs is part of a more general capacity of the mind to relate the organism to the world, any complete account of speech and language requires an account of how the mind/brain relates the organism to reality."

Isn’t the above similar to just saying: “if we define our terms we can say whatever we want.” — Fire Ologist

Not quite, but in Speech Acts John Searle says, “I take it to be an analytic truth about language that whatever can be meant can be said.” -

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water." Familiarity with water is a precondition for familiarity with the English sign "water." — Leontiskos

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water." Familiarity with water is a precondition for familiarity with the English sign "water." — Leontiskos

I agree as a rule, although the tricky thing is that one might indeed become familiar with something first through signs that refer to some other thing. We can learn about things through references to what is similar, including through abstract references. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm not so sure. What would an example be? That we become familiar with transparency, and because water is transparent our familiarity with transparency is therefore familiarity with water?

I would say that familiarity with transparency is not itself familiarity with water. Nevertheless, someone could say, "You don't know what water is, but you know what transparency is, and you should trust me when I tell you that water is transparent." We can learn something about water through this sort of trust (and philosophy is always built on faith of this kind), but on my view this counts as "familiarity with water" (via someone who has knowledge). Once even that sort of second-hand familiarity is in place the English sign "water" is available to us, at least in a limited sense. Still, this won't work if our source has no familiarity with water.

(I suppose I am also presuming that the one who takes on faith the claim that water is transparent is also differentiating between water and 'water', and is thus aware that their source is making use of a sign.)

And the difference between these two models lies in the question: in the second model, what is signified: the object, or an interpretation called forth by the sign (the meaning)? That seems to be the essence of the question here to me. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is good. I would only add that Walker Percy's simplified triadic model may be helpful in a place like TPF, given that even skeptics are generally able to admit that not every sign-user has an identical understanding of every sign:

---

- :up:

I would simply want to ask @J what his telos is. What is his aim? Truth? Pluralism? The moral avoidance of strong knowledge claims (which might create conflict)? And if he is aiming at multiple different things, then the question is whether those various aims are mutually consistent.

For example, his claim that he is not a relativist (and that he believes in truth) is somewhat at odds with his conviction that strong truth-claims are morally problematic. Perhaps he solves the riddle by defining truth as intersubjective agreement, but the difficulty there is that we all know that there is a difference between intersubjective agreement and truth, and that we are even at times morally obliged to disregard or even oppose the falsehood represented by the intersubjective agreement.

At the end of the day I would simply say that although we must avoid injustice, nevertheless it is not unjust to affirm what one believes to be true (at a general level). Even with something like racism, it is not unjust when it is in earnest, as some of the cases that Daryl Davis engaged demonstrate. One must be mindful of the ways in which they engage others, but to earnestly believe that something is true is never unjust. One might even avoid pronouncing a truth for the sake of some communal good, but it does not follow that one should not hold the thing as being true. The reason the left frets over this sort of thing is because they conflate per se and per accidens causality and implication. -

Banno

30.6kJohn Searle says, “I take it to be an analytic truth about language that whatever can be meant can be said.” — Richard B

Banno

30.6kJohn Searle says, “I take it to be an analytic truth about language that whatever can be meant can be said.” — Richard B

He visited us here, long ago. I asked him about that aphorism, and if I recall correctly he expressed some regret towards it, not becasue it was wrong but becasue it caused considerable misunderstanding. I understood him to be saying that many folk had misunderstood him as claiming that for instance children could not use meanings becasue they had not developed the ability to use language. That is, folk missed the implicit conditional - if it can be meant then it can be said - to be claiming that only speech had meaning.

Must have been in the previous incarnation of this forum.

added: the stuff just said appeared while I was writing this post - another coincidence. It may be an example of the sort of thing Searle was complaining about. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- I don't think anything you said followed from anything I said, which seems standard at this point. You've gotten to the point where you're not even reading posts.

Leontiskos

5.6k- I don't think anything you said followed from anything I said, which seems standard at this point. You've gotten to the point where you're not even reading posts. -

Banno

30.6kSo support that contention.

Banno

30.6kSo support that contention.

Or leave the vague ad hominem hanging, in your increasingly tedious passive aggressive fashion. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kThe capacity of speech acts to represent objects and states of affairs in the world is an extension of the more biologically fundamental capacities of the mind (or brain) to relate the organism to the world by way such mental states as belief and desire, and especially through action and perception. — Richard B

Fire Ologist

1.7kThe capacity of speech acts to represent objects and states of affairs in the world is an extension of the more biologically fundamental capacities of the mind (or brain) to relate the organism to the world by way such mental states as belief and desire, and especially through action and perception. — Richard B

Ok, that is a mouthful of speech activity. Let me try to break it down.

“mind (or brain) to relate the organism to the world”

You have at least two physical pivot points here. Brain in an organism, and the world.

And the two relate “by way such mental states as belief and desire, and especially through action and perception.”

I don’t follow.

Since speech acts are a type of human action, and since the capacity of speech to represent objects and states of affairs is part of a more general capacity of the mind to relate the organism to the world, any complete account of speech and language requires an account of how the mind/brain relates the organism to reality." — Richard B

“a more general capacity of the mind to relate the organism to the world”

Isn’t whatever that means sort of the whole question? How can this be asserted as a premise to lead to some other conclusion, when what/how/whether “a more general capacity of the mind to relate the organism to the world” is the question?

“I take it to be an analytic truth about language that whatever can be meant can be said.” — Richard B

I can see ways to make this be true and ways to make this be false, meaning, it is an interesting statement, and I think worth pondering, but it feels treacherous. -

Richard B

569

Richard B

569

John Searle is a unique and interesting philosopher. He is a scientific realist who tip toes ever so close to being an idealist/indirect realist, while simultaneously and rebelliously rejecting later Wittgenstein's creed that philosophy should only describe and not theorize. You could say he is an internalist when it comes to meaning, aka "Meanings are just in the head". -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

There are other examples we can use. Hesperus=Phosphorus is common; concluding that the star seen in the evening is the same object as that seen later in the morning required some astute observation and plotting of the position of the star. Now we think that ☐(Hesperus=Phosphorus).

Or that Gold has atomic number 79. Not known until the notion of atomic numbers was developed and found useful. But thereafter a necessary fact.

What's salient is that being gold, or Hesperus, or water, is not determined in the same way as having atomic number 79, or being Phosphorus, or being H₂O. It's discovered, by looking about the world. Previously modal theorists had supposed that no necessities were to be discovered in this way, supposing instead that they were all artefacts of language, and so found just by thinking.

Does that help?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- 'The real is rational, and the rational is real' (philosophy as idealism/humanism)

- Turning philosophy forums into real life (group skype chats/voice conference etc.)

- Does Art Reflect Reality? - The Real as Surreal in "Twin Peaks: The Return"

- Things that aren't "Real" aren't Meaningfully Different than Things that are Real.

- Why are universals regarded as real things?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum