-

Christoffer

2.5k

Christoffer

2.5k

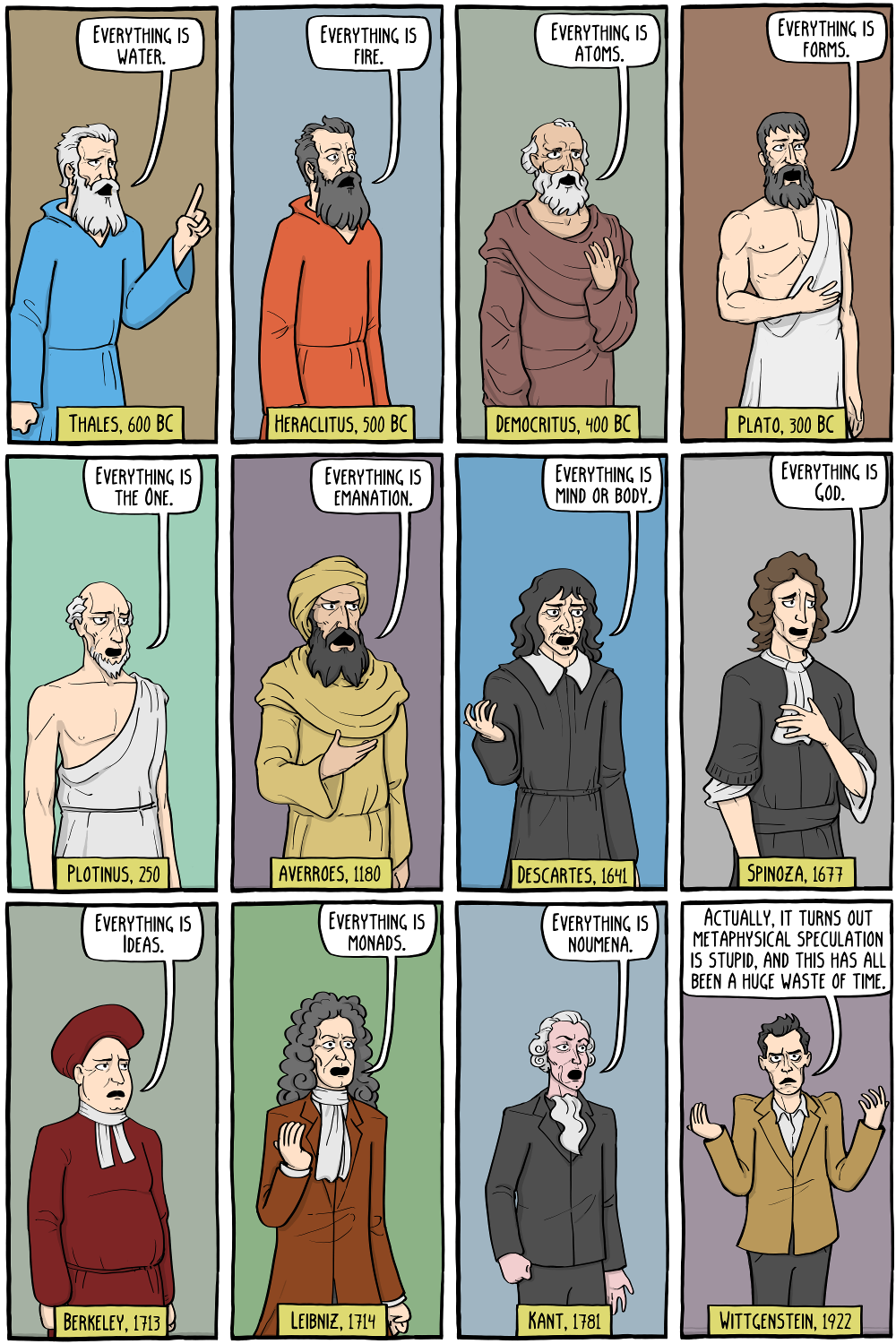

Hehehe, yup, science have made metaphysics kinda irrelevant. We can use it for things that's still hard to prove, with proper logical arguments, but I find most metaphysical ideas today to exist among religious, spiritual people who can only form ideas around their beliefs rather than facts or people who think their personal opinions are facts, but I've rarely seen any proper metaphysical philosophy that don't use scientific premisses and facts. -

Marchesk

4.6k

Marchesk

4.6k

Except, Democritus was on to something, we're still debating some of those things, like the mind/body problem (consciousness in particular). Witty didn't end the speculation. He just added to the speculation that it might largely be the result of a misunderstanding of how language works. -

Marchesk

4.6kHehehe, yup, science have made metaphysics kinda irrelevant. — Christoffer

Marchesk

4.6kHehehe, yup, science have made metaphysics kinda irrelevant. — Christoffer

Not really. Science has been able to answer some questions that used to be metaphysical. But there are plenty of questions that we don't know how to investigate empirically. Questions about consciousness, the interpretation of QM, laws of nature, causality, the nature of time, mereology, supervenience, the nature of perception, and various debates over realism vs anti-realism. -

Marchesk

4.6kEverything is what it is. — Michael

Marchesk

4.6kEverything is what it is. — Michael

Which isn't saying anything. Water is water.

Okay, but what makes water be like water and not like glass? Well, turns out ordinary matter has a chemical composition which determines that. And how does chemical composition determine the properties of water? Physics. And what determines physics? And now you're on to cosmology, which is one step removed from asking metaphysical questions. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

I think Collingwood makes a pretty good case that the only possible science of metaphysics would consist in a history of absolute presuppositions. Science, whether modern, medieval or ancient always involves indemonstrable metaphysical presuppositions; so Wittgenstein was dead wrong in saying (if he did say) that metaphysics is always merely an abuse of language. Of course this is not to say that there have not been examples of metaphysical thought which do consist in abuse of language. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kEverything is what it is. — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kEverything is what it is. — Michael

Wittgenstein was reportedly fond of Bishop Butler's aphorism: "Everything is what it is and not another thing".

Arguably, this isn't so much an anti-metaphysical attitude as it is a repudiation of reductive analysis. Arguably, also, Wittgenstein's own philosophical quietism can be construed as being consistent with the practices of connective analysis, and of descriptive metaphysics, in the sense Peter Strawson used those phrases. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

What is a "absolute presupposition"?I think Collingwood makes a pretty good case that the only possible science of metaphysics would consist in a history of absolute presuppositions. ...so Wittgenstein was dead wrong in saying (if he did say) that metaphysics is always merely an abuse of language. — Janus

They appear not at all dissimilar to "hinge propositions". -

Janus

17.9kAs I understand it. according to Collingwood absolute presuppositions are the fundamental principles upon which the fields of human inquiry depend. They are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity.

Janus

17.9kAs I understand it. according to Collingwood absolute presuppositions are the fundamental principles upon which the fields of human inquiry depend. They are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThey are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThey are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity. — Janus

OK, if we can't speak of them in terms of whether they are true or false, why not identify them for what they are then? They're uncertain thoughts.

As I understand it. according to Collingwood absolute presuppositions are the fundamental principles upon which the fields of human inquiry depend. — Janus

Collingwood seems to have a negative view of epistemology. He thinks that the fields of human inquiry are based on uncertain thoughts. -

mcdoodle

1.1kAs I understand it. according to Collingwood absolute presuppositions are the fundamental principles upon which the fields of human inquiry depend. They are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity. — Janus

mcdoodle

1.1kAs I understand it. according to Collingwood absolute presuppositions are the fundamental principles upon which the fields of human inquiry depend. They are understood to be different than propositions in that it is inappropriate to speak about them in terms of truth and falsity. — Janus

My reading of Collingwood is that it's about questioning and absolute presuppositions. When you study a philosopher you come up with questions met with answers which lead to further questions which lead...eventually, to the point where the views of that philosopher offer no answer. Here are the absolute presuppositions which, I agree with Banno, bear a remarkable resemblance to hinge propositions.

As someone on the old forum said to me, one very odd thing about Collingwood is that he held these seriously anti-ontological views (I don't think they are anti-epistemological) but he also went to church every Sunday and engaged in acts of worship. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

Yes, I think what you say is kind of true, though not only of philosophy, but of science, economics, anthropology; in short of all domains of inquiry. As absolute presuppositions are also operative in the kinds of everyday commonsense beliefs that we could never foresee being overturned, they may be said to resemble hinge propositions. The difference is that in the domains of inquiry the absolute presuppositions are things we can be said to necessarily suppose, rather than believe, in order to carry out any investigation at all.

So, for example that the cosmos is mind could be the absolute presupposition of an idealist philosopher, which is required for the further elaboration of his idealist philosophy. From within that philosophy the truth of its founding assumption can never be questioned; the question simply cannot arise. Similarly from within the methodological naturalism of the physical sciences the absolute presupposition that the cosmos is material cannot be questioned.

There is also some commonality with Peirce's idea of 'regulative assumptions'. This paper:https://slideheaven.com/regulative-assumptions-hinge-propositions-and-the-peircean-conception-of-truth.html explores the commonality between Peirce's regulative assumptions and Wittgenstein's "hinge propositions". Here is the abstract:

Abstract

This paper defends a key aspect of the Peircean conception of truth—the

idea that truth is in some sense epistemically-constrained. It does so by exploring

parallels between Peirce’s epistemology of inquiry and that of Wittgenstein in On

Certainty. The central argument defends a Peircean claim about truth by appeal to a

view shared by Peirce and Wittgenstein about the structure of reasons. This view

relies on the idea that certain claims have a special epistemic status, or function as

what are popularly called ‘hinge propositions’

This passage from Cheryl Misak's The American Pragmatists deals with Peirce's notion of 'regulative assumptions':

His answer is that it is a regulative assumption of inquiry that, for any matter into which we are inquiring, we would find an answer to the question that is pressing in on us. Otherwise, it would be pointless to inquire into the issue: “the only assumption upon which [we] can act rationally is the hope of success” (W 2: 272; 1869). Thus the principle of bivalence—for any p, p is either true or false—rather than being a law of logic, is a regulative assumption of inquiry. It is something that we have to assume if we are to inquire into a matter. Peirce is clear and explicit on this point. To say that bivalence is a regulative assumption of inquiry is not a claim about special logical status (that it is a logical truth); nor is it a claim that it is true in some plainer sense; nor is it a claim about the nature of the world (that the world is such that the principle of bivalence holds). The principle of bivalence, he says, is taken by logicians to be a law of logic by a “saltus”—by an unjustified leap (NE 4: xiii). He distinguishes his approach from that of the transcendentalist:

when we discuss a vexed question, we hope that there is some ascertainable truth about it, and that the discussion is not to go on forever and to no purpose. A transcendentalist would claim that it is an indispensible “presupposition” that there is an ascertainable true answer to every intelligible question. I used to talk like that, myself; for when I was a babe in philosophy my bottle was filled from the udders of Kant. But by this time I have come to want something more substantial.*

Misak, Cheryl. The American Pragmatists (The Oxford History of Philosophy) (pp. 50-51). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition.

* the bolded text is Peirce's own words

As someone on the old forum said to me, one very odd thing about Collingwood is that he held these seriously anti-ontological views (I don't think they are anti-epistemological) but he also went to church every Sunday and engaged in acts of worship. — mcdoodle

I don't know much about it, but apparently Collingwood accepted the truth of his own version of the Ontological argument, which might indeed seem odd considering his notion of the historical relativity of absolute presuppositions. -

Janus

17.9kOK, if we can't speak of them in terms of whether they are true or false, why not identify them for what they are then? They're uncertain thoughts. — Metaphysician UndercoverCollingwood seems to have a negative view of epistemology. He thinks that the fields of human inquiry are based on uncertain thoughts. — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

17.9kOK, if we can't speak of them in terms of whether they are true or false, why not identify them for what they are then? They're uncertain thoughts. — Metaphysician UndercoverCollingwood seems to have a negative view of epistemology. He thinks that the fields of human inquiry are based on uncertain thoughts. — Metaphysician Undercover

An "uncertain thought" is a thought about which we are undecided as to whether it is true or not. Absolute presuppositions are understood to be things we necessarily suppose in order to investigate anything at all, and about which it is inappropriate to think in terms of their being propositions which could be demonstrated to be true or false; so...no. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kIn any area of endeavor where thinking is involved, you get to ask if your process - whatever it is - is valid (true, provable, whatever qualifying word you want). Pretty quickly you get to, in some areas, axioms. Within the process or activity, the axioms are - well, we all know what axioms are, yes? Outside the process, a person may question axioms, but while the answers may be interesting, they are not relevant to the process itself - unless they destroy the process. — tim wood

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kIn any area of endeavor where thinking is involved, you get to ask if your process - whatever it is - is valid (true, provable, whatever qualifying word you want). Pretty quickly you get to, in some areas, axioms. Within the process or activity, the axioms are - well, we all know what axioms are, yes? Outside the process, a person may question axioms, but while the answers may be interesting, they are not relevant to the process itself - unless they destroy the process. — tim wood

What do you mean, "we all know what axioms are"? An axiom in mathematics exists by a completely different standard from an axiom in philosophy. And I am sure there are many in between.

It's reasonable to question axioms, because how the results of the questioning break influences, rebounds back to, the endeavor. — tim wood

In philosophy an axiom is a self-evident truth. It is based in experience, description, and definition. It's really not reasonable to question an axiom unless you have reason to believe that the description or definition is inaccurate. In this case one might question it, because the so-called "truth" is not self-evident to that person who sees a fault in the description or definition.

I know, all sorts of people get immediately exercised at the notion that something can be efficacious independent of its truth, but the idea is that it is an absolute presupposition, and the idea of an absolute presupposition is that you have to start somewhere. This isn't to say that the starting point is weighed and tested and argued on; usually it isn't. Absolute presuppositions evolve. And they change, usually as the result of a significant rupture in understanding and culture, whether large or small. — tim wood

Why not start with description rather than "absolute presupposition"?

Here's a not very good example of an absolute presupposition. Suppose you need a sterile bandage. You find some at home, and you (relatively) presuppose that they're sterile. But they've been in your cabinet for five years, so it's reasonable to ask if these supposedly sterile bandages are really sterile. You decide you need to be sure, so you go to the pharmacy to buy some new sterile bandages. The presupposition that the pharmacy bandages are sterile is an absolute presupposition in the sense that they're what you're going to use, and the question as to their sterility does not arise (it is absolutely presupposed). — tim wood

What does this have to do with metaphysics?

An "uncertain thought" is a thought about which we are undecided as to whether it is true or not. Absolute presuppositions are understood to be things we necessarily suppose in order to investigate anything at all, and about which it is inappropriate to think in terms of their being propositions which could be demonstrated to be true or false; so...no. — Janus

If we suppose them, we believe them to be true. I wouldn't suppose something I didn't believe to be true, except for the purpose of a counterfactual. So it's not true to say that we cannot speak of them in terms of truth or falsity, we are supposing them not for the purpose of counterfactual, we are supposing them as truth, therefore we speak of them as true.

Even if we suppose them as counterfactuals, they are uncertain thoughts. So either way, if we suppose them as true when we have no reason to believe them as true, or if we suppose them as counterfactual, they are uncertain thoughts. -

Janus

17.9kIf we suppose them, we believe them to be true. — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

17.9kIf we suppose them, we believe them to be true. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, assuming something for the sake of investigation does not entail that I must believe what I am assuming to be true. Look at the example of bivalent logic in the passage quoted above from Misak's book on the American pragmatists. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

OK, but it's still nothing more than an uncertain thought under your definition

An "uncertain thought" is a thought about which we are undecided as to whether it is true or not. — Janus -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

No, it's not an uncertain thought under that definition, because its truth or falsity is not in question; we are not undecided about its truth or falsity; it is simply irrelevant.

It is not an uncertain thought in any other sense, either, because it may be as clearly conceived as you like. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNo, it's not an uncertain thought under that definition, because its truth or falsity is not in question; we are not undecided about its truth or falsity; it is simply irrelevant. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNo, it's not an uncertain thought under that definition, because its truth or falsity is not in question; we are not undecided about its truth or falsity; it is simply irrelevant. — Janus

Yes the truth or falsity clearly is in question, according to that quoted passage. Did you read it? We hope to someday resolve it as to truth or falsity, though it is not resolvable at the time of making the presupposition.. From that quoted passage:

“the only assumption upon which [we] can act rationally is the hope of success” (W 2: 272; 1869). — Janus

when we discuss a vexed question, we hope that there is some ascertainable truth about it, and that the discussion is not to go on forever and to no purpose. — Janus

The fact that we hope it will some day be resolved as true or false indicates that it is something which we are undecided about. It is an uncertain thought.

It is not an uncertain thought in any other sense, either, because it may be as clearly conceived as you like. — Janus

That a thought is clearly conceived doesn't make it a certainty. -

Janus

17.9k“the only assumption upon which [we] can act rationally is the hope of success” (W 2: 272; 1869). — Janus

Janus

17.9k“the only assumption upon which [we] can act rationally is the hope of success” (W 2: 272; 1869). — Janus

when we discuss a vexed question, we hope that there is some ascertainable truth about it, and that the discussion is not to go on forever and to no purpose. — Janus

The fact that we hope it will some day be resolved as true or false indicates that it is something which we are undecided about. It is an uncertain thought. — Metaphysician Undercover

You're misunderstanding what is written there. "We hope that there is some ascertainable truth about it" means that we proceed as if there were, otherwise we would not enquire; it does not mean that we are in a state of uncertainty about whether there is "some ascertainable truth". I'ts a subtle, but salient, difference you are missing.

Think of it another way in terms of another example. Science (leaving aside QM) proceeds on the assumption that every event must have a cause. Science is not concerned with proving that every event must have a cause, because that would seem to be impossible, since we cannot possibly examine every event or even show definitively that the events we can examine had causes. Rather, an absolute presupposition of science is that every event has a cause; if we didn't think in terms of causation, science would be impossible.

So we can say that whether or not every event has a cause is undecidable, but that does not mean that we are undecided about the truth or falsity of "every event must have a cause"; in fact we are not undecided about that at all, because we have decided that it is undecidable, and we have decided to adopt it nonetheless, because we have decided that it is indispensable to our inquiries.

That a thought is clearly conceived doesn't make it a certainty. — Metaphysician Undercover

If the idea is clearly conceived and we are certain that it is indispensable to our inquiries, then it cannot be counted as an "uncertain thought". -

creativesoul

12.2kAttitudes towards statements of thought are where certainty and uncertainty reside. Attitudes.

Thoughts aren't the sort of thing that can be certain or uncertain. Thoughts do not doubt their own truth. Rather, they presuppose it somewhere along the line. Uncertainty arises from doubt. It is a product thereof. If a thing cannot doubt, it is not the sort of thing that can be uncertain. Thoughts aren't the sort of thing that can doubt.

Language use matters.

The irony... :lol:

I overstated the importance of language...

:joke:

Edited to add the following exception...

To be clear... creatures without statements can be uncertain about the immediate future as well. My cat can be uncertain about the noise it heard, or about the stability of what she's about to step onto. Her thoughts about the noise and the structure aren't uncertain. Rather, she is as a result of having those thoughts. -

creativesoul

12.2kIt's annoying, MU your deliberate misreading... — tim wood

I do not believe that it is deliberate. It's very annoying none-the-less. -

creativesoul

12.2kAbsolute presuppositions are understood to be things we necessarily suppose in order to investigate anything at all... — Janus

This reminds me of what Kant called a priori. That which is necessarily presupposed by experience itself.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum