-

Streetlight

9.1kOrienting Remarks for §46 Onwards

Streetlight

9.1kOrienting Remarks for §46 Onwards

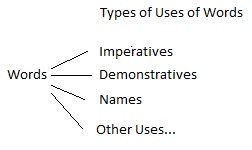

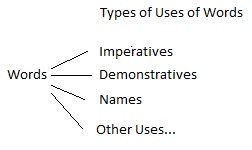

§46 marks yet another turn in the argument of the PI, and probably the most radical so far. Up to now, it can be said that Witty's concern has been to establish that there can be different kinds of uses of words (and not just one kind - naming, as with Augustine). That is, it's not just that different words have different meanings (as if words merely differed by 'degree'), but that the meanings of words also differ in kind: we can distinguish between types of words (with Witty so far having examined, roughly in order, imperatives, demonstratives, and names). Diagrammatically, we might be able to put it this way, with the right hand side of the diagram being what has been covered so far:

§46 onwards turns its attention to the left hand side of this diagram. So far, the question of exactly what is subject to different kinds of use hasn't really been brought up, other than saying that it is 'words' which have different kinds of use. In fact, the examples offered by Witty so far have themselves largely been individual words like 'slab!' or 'Nothung'. It is this assumption that is here put into question in the discussion after §46. The question could be put like this: what is the 'unit' of meaning? It is a word? A sentence? A proposition? In fact, is it legitimate at all to speak of a unit of meaning? And if it is, under what conditions?

This concern can actually goes all the way back to §1 where Witty already signposted his intention. To recall:

§1: "In [Augustine's] picture of language we find the roots of the following idea: Every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated with the word. It is the object for which the word stands."

As I mentioned earlier in my commentary on this line, I said that Witty will try and show both that (A.) words don't just correlate to objects (there are different kinds of words (§1-§45)), but also that (B.) it cannot be taken for granted what counts as the natural 'unit' of meaning. §46 onwards tackles this second aspect of Witty's objection to the Augustinian picture. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k46. A passage from Plato's Theaetetus is quoted in which Socrates is observed describing what "some people say"; that the "primary elements", out of which everything is composed, can be named but not described nor defined in any way. Nothing can be predicated of the primary element, it simply "exists in its own right". Wittgenstein states that Russell's "individuals", and his own "objects" in the Tractatus are such "primary elements".

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k46. A passage from Plato's Theaetetus is quoted in which Socrates is observed describing what "some people say"; that the "primary elements", out of which everything is composed, can be named but not described nor defined in any way. Nothing can be predicated of the primary element, it simply "exists in its own right". Wittgenstein states that Russell's "individuals", and his own "objects" in the Tractatus are such "primary elements". -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThere is a fundamental, yet very simple problem with this idea of "primary elements" which Wittgenstein exposes at 48. The problem with the concept of these "elements" is that the very description of them, as something which cannot be described, is in itself, in that sense, contradictory. Something which cannot be described has been described. If we assume the existence of these elements we lose the capacity of the fundamental laws of logic, starting from the law of identity. We assume individual "elements", but they have by stipulation, absolutely no distinguishing features which would make them individual, so they are necessarily all the same element.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThere is a fundamental, yet very simple problem with this idea of "primary elements" which Wittgenstein exposes at 48. The problem with the concept of these "elements" is that the very description of them, as something which cannot be described, is in itself, in that sense, contradictory. Something which cannot be described has been described. If we assume the existence of these elements we lose the capacity of the fundamental laws of logic, starting from the law of identity. We assume individual "elements", but they have by stipulation, absolutely no distinguishing features which would make them individual, so they are necessarily all the same element.

So we have the example at 48. Are the three G's three distinct elements, or are they all the same element?

But I do not know whether to say that the figure described by our

sentence consists of four or of nine elements! Well, does the sentence

consist of four letters or of nine?—And which are its elements, the

types of letter, or the letters? Does it matter which we say, so long as

we avoid misunderstandings in any particular case?

But if we go deeper we see that the different squares are already distinguished by some properties. they are different according to their colours, and separated by lines. So if Wittgenstein were to adhere to the stipulation of "primary element", there could be no distinguishing one square from another by means of colour, and if we were steadfast to the rule, even the squares could not be distinguished one from the other by means of shape and position. Therefore the final question is moot. "Does it matter which we say, so long as we avoid misunderstandings in any particular case?" If there really was a type of thing called "primary element", as described, understanding would be impossible. -

Luke

2.7k44. Having previously argued that names do not require a bearer to be used in the language-game, Wittgenstein now changes tack and asks us to imagine a language-game in which names (i.e. "signs which we should certainly include among names") are only used in the presence of a bearer, and therefore "could always be replaced by a demonstrative pronoun and the gesture of pointing".

Luke

2.7k44. Having previously argued that names do not require a bearer to be used in the language-game, Wittgenstein now changes tack and asks us to imagine a language-game in which names (i.e. "signs which we should certainly include among names") are only used in the presence of a bearer, and therefore "could always be replaced by a demonstrative pronoun and the gesture of pointing".

45. "The demonstrative "this" can never be without a bearer". W suggests that as long as there is a bearer, then the word "this" also has a meaning, regardless of whether the bearer is simple or complex. However, it does not make the demonstrative "this" into a name, "for a name is not used with, but only explained by means of, the gesture of pointing". This is logically similar to his remark at §38 that the word "this" is not defined demonstratively (e.g. [not] "This is called 'this'".)

46. "What lies behind the idea that names really signify simples?" W indicates that this has long been a common philosophical assumption, quoting Socrates in the Theaetetus and noting that the same idea has also been entertained by himself and Bertrand Russell.

47. W asks what are the simple constituents of (e.g.) a chair? Is it the wood, or the molecules, or the atoms of which it is composed? He notes "'Simple' means: not composite. And here the point is: in what sense 'composite'?" He reveals the answer: "It makes no sense at all to speak absolutely of the 'simple parts of a chair'".

W now speaks of his own visual image (e.g. of a tree) and asks of what simple parts it is composed. W considers the question vague: what sense of 'composite' are we talking about? "The question "Is what you see composite?" makes good sense if it is already established what kind of complexity - that is, which particular use of the word - is in question."

W anticipates the counterargument: "But isn't a chessboard, for instance, obviously, and absolutely, composite?" W answers that you are probably thinking of the chessboard's composition as 32 white and 32 black squares, but he notes that you could also say "that it was composed of the colours black and white and the schema of squares". This might sound very similar, but the point is that it has not been established what we mean by 'composite' here. You can't just say that it is composite without first deciding what we mean by that. As W says it is misguided to ask whether an object is composite outside of a particular language-game.

He concludes: "We use the word "composite" (and therefore the word "simple") in an enormous number of different and differently related ways...To the philosophical question: "Is the visual image of this tree composite, and what are its component parts?" the correct answer is: "That depends on what you understand by 'composite'." (And that is of course not an answer but a rejection of the question.)" -

Banno

30.6kNeat analysis. I like it.

Banno

30.6kNeat analysis. I like it.

Simples are what had names for the early Wittgenstein (§46).

So the discussion of simples does follow on naturally from the discussion of names.

(Found the damn section sign, finally. ) -

Streetlight

9.1k§46

Streetlight

9.1k§46

So, like I said, §46 marks a change in the argumentative strategy of the PI, with Witty no longer looking at types of uses of words, but rather, more closely at what are considered 'words' - what is it that are 'used'? He begins with a passage from the Theaetetus, which is actually pretty damn complex. We can break it down like this:

For Socrates, to each so-called primary element corresponds a name (there is a one-to-one mapping between name and primary element). Names however, do nothing but 'signify' primary elements: they tell us nothing about them other than that they exist or not. Now, it is important here that primary elements and their names are associated with existence. They are ontological primitives.

Importantly, one cannot give an explanatory account of these primitives, because these primitives are what do any kind of explaining. It is only when primitives are composed together, that we can have 'explanatory language', language that does more than just name, and hence, determine a thing's existence. I bring to the fore here the question of existence, because the remarks that follow will contest not only what counts as a complex and a simple (which is what is often focused upon), but far more importantly, the very status of complexes and simples as ontological. In place of ontology, Witty will substitute grammar. We'll see what this means as we continue. -

Luke

2.7k§48. W considers a language-game which conforms to the account from the Theaetetus which is presented at §46, in which names stand for primary elements. "The language serves to describe combinations of coloured squares on a surface" which form a 3x3 matrix or "complex". The squares are red, green, white and black, and the words of the language are (correspondingly) "R", "G", "W" and "B", where "a sentence is a series of these words". The order of the squares has an arrangement like the numbers of a (push-button) telephone, so the sentence "RRBGGGRWW" takes the arrangement of:

Luke

2.7k§48. W considers a language-game which conforms to the account from the Theaetetus which is presented at §46, in which names stand for primary elements. "The language serves to describe combinations of coloured squares on a surface" which form a 3x3 matrix or "complex". The squares are red, green, white and black, and the words of the language are (correspondingly) "R", "G", "W" and "B", where "a sentence is a series of these words". The order of the squares has an arrangement like the numbers of a (push-button) telephone, so the sentence "RRBGGGRWW" takes the arrangement of:

RRB

GGG

RWW

(but with the above "words"/letters replaced by their respective colours.)

Wittgenstein states that the sentence "RRBGGGRWW" "is a complex of names, to which corresponds a complex of elements. The primary elements are the coloured squares." Wittgenstein states that it is natural to consider these primary elements (coloured squares) as simple. However, he notes that "under other circumstances" he might call a monochrome square "composite" because it consists "perhaps of two rectangles, or of the elements colour and shape". Or, we might consider a smaller area "to be 'composed' of a greater area and another one subtracted from it". He notes that "we are sometimes even inclined to conceive the smaller as the result of a composition of greater parts, and the greater as the result of a division of the smaller". Wittgenstein now questions whether the sentence "RRBGGGRWW" contains four or nine letters, and whether an element is a type of letter (i.e. a colour) or an individual letter.

Reiterating his message from §47, whether these primary elements are 'simple' or 'composite' depends on how we agree to use those terms; what we mean by 'simple' and 'composite'. As he states lastly: "Does it matter which we say, so long as we avoid misunderstandings in any particular case?" -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kReiterating his message from §47, whether these primary elements are 'simple' or 'complex' depends on how we agree to use those terms; what we mean by 'simple' and 'complex'. As he states lastly: "Does it matter which we say, so long as we avoid misunderstandings in any particular case?" — Luke

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kReiterating his message from §47, whether these primary elements are 'simple' or 'complex' depends on how we agree to use those terms; what we mean by 'simple' and 'complex'. As he states lastly: "Does it matter which we say, so long as we avoid misunderstandings in any particular case?" — Luke

i believe the dichotomy of simple and composite at 47 ought to be treated as a digression. What he demonstrates is that it doesn't make sense to think of things as either simple or as composite, in an absolute sense, as these are relative terms. So this way of thinking is not applicable to "primary elements", which as foundational, are meant to be absolutes. We ought not to think of primary elements as either simple or composite. However, we can maintain the definition of "primary elements" as offered at 46. And this definition of "primary elements", as something which cannot be defined, is inherently self-refuting. So the question of how we ought to describe the primary elements, as either simple or as composite, in order to avoid misunderstanding, is completely irrelevant because primary elements cannot be described. Furthermore, since the notion of "primary elements" is self-refuting, we ought to consider it, in itself, to be a misunderstanding. -

Luke

2.7k

Luke

2.7k

Since he says little about "primary elements" and speaks much more about simples and composites from 46-48, then I disagree that it's merely a "digression". If so, it's quite a long digression. Perhaps some of what you say could be deduced from what he says, but you're largely missing the point about meaning being undetermined outside a language-game. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kPerhaps some of what you say could be deduced from what he says, but you're largely missing the point about meaning being undetermined outside a language-game. — Luke

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kPerhaps some of what you say could be deduced from what he says, but you're largely missing the point about meaning being undetermined outside a language-game. — Luke

No, I'm not missing that point, that's quite clear, as a premise of sorts. But there's a bigger point being made which extends into the ontological status of "primary elements". So I saw the discussion of the relation between simples and composites as a digression in relation to this ontological matter. Maybe I was wrong, and that shouldn't be classified as a digression.

But look at how this section unfolds. He starts 46 by asking about simples. Then he quotes Plato concerning "primary elements", and implies that there is a relation between "simples" and "primary elements". Now, it appears that "primary elements" are intended by those philosophers who posit them, to be some sort of absolute, as the foundation for all reality. But then at 47 Wittgenstein demonstrates that simples cannot be absolutes, as "simple" gets its meaning from 'composite", and the meaning of "composite" depends on the way that the word is being used (the particular language-game) It appears like he may be driving a wedge between "primary elements" and "simples".

So, consider 48, the example of the coloured squares.

Here the sentence is a complex of names, to which corresponds a complex of elements. The primary elements are the coloured squares. "But are these simple?"—I do not know what else you would have me call "the simples", what would be more natural in this language-game. But under other circumstances I should call a monochrome square "composite", consisting perhaps of two rectangles, or of the elements colour and shape.

Notice, that the primary elements are such (primary elements) simply because they are designated as such. The coloured squares are designated as "primary elements". But are they "the simples"? Yes, they are in this language-game, but this is only because the coloured squares are designated as primary elements in this game. In another context, the elements might be divided further, therefore something else would be designated as primary elements, and accordingly, the language-game would have to devise some other way to represent the primary elements of this game. Aren't the primary elements, supposed by the philosophers, to be the absolutes in the foundation of reality though? How is it that they have now become relative to the particular language-game?

Then the issue with such primary elements, involving the law of identity, is exposed:

But I do not know whether to say that the figure described by our sentence consists of four or of nine elements! Well, does the sentence consist of four letters or of nine?—And which are its elements, the types of letter, or the letters?

What is identified as an "element", is it a type or is it a particular? Then he proceeds to question at 49, 50, what is meant by "element" in that sense of "primary element". -

Sam26

3.2kI tend to agree with Conant/Diamond here insofar as I take it that this is what Witty understands therapy to consist in and why the notion is so central to his meta-philosophy. You can't shout Terrapin into understanding this point, as you seem to be doing in your post. Nor can you force him to engage in the sort of philosophical therapy he needs to understand it so long as he refuses to work with L.W. qua therapist in order to fully realize the point through a sort of anerkennen (i.e. if he reads Wittgenstein as his buddy rather than as a philosophical diagnostician who needs to be allowed some pathos of distance in order to show the reader what he wants him to see). — John Doe

Sam26

3.2kI tend to agree with Conant/Diamond here insofar as I take it that this is what Witty understands therapy to consist in and why the notion is so central to his meta-philosophy. You can't shout Terrapin into understanding this point, as you seem to be doing in your post. Nor can you force him to engage in the sort of philosophical therapy he needs to understand it so long as he refuses to work with L.W. qua therapist in order to fully realize the point through a sort of anerkennen (i.e. if he reads Wittgenstein as his buddy rather than as a philosophical diagnostician who needs to be allowed some pathos of distance in order to show the reader what he wants him to see). — John Doe

I think Conant and Diamond are incorrect in the way they interpret parts of Wittgenstein, but that's a subject for a different thread.

I don't know why you would characterize my reply to Terrapin as shouting, maybe because of the force of the comment, I'm not sure. In fact, I tried to inject a bit of humor into the comment. When I write I'm not only writing as a reply to a specific post, but I'm writing to those who might be following along, so I think it's a good idea to reply to certain posts, even if it seems to be not worth the effort as Banno suggested. -

Luke

2.7k

Luke

2.7k

Good post. You are right to point out that Wittgenstein is arguing against the view "that "primary elements" are intended by those philosophers who posit them, to be some sort of absolute, as the foundation for all reality,". StreetlightX also notes the importance of these 'ontological primitives' in his latest post, with the elegant description of "a one-to-one mapping between name and primary element". However, I don't consider this to be an entirely new development, since W has been arguing against any presupposed 'occult process' or 'queer connection' between name and object since at least section §37. I maintain that at §47 and §48 he is drawing our attention to the meaning/use of the terms 'simple' and 'composite', but I acknowledge that he is also attacking the deeply ingrained presupposition of a 'queer connection' between name and object in the process.

So, as I said earlier, I thought there was some truth to what you said, but did not agree with your use of the term 'digression'. I also didn't really understand your reference to primary elements being "self-refuting". -

Streetlight

9.1k§47 (Exegesis)

Streetlight

9.1k§47 (Exegesis)

Following §46, in which the question of the simple and the complex was bound up with questions of existence in Socrates, §47 will begin the process of substituting ontology for grammar: questions about existence for questions about uses of words. It begins with a rhetorical question that, tellingly, once again asks about the composition of ‘reality’:

§47: "But what are the simple constituent parts of which reality is composed?” (my emphasis).

To this question, Wittgenstein will reply that we can only make sense of the notions of the simple and the composite by reference to how the word(s) in question are put to use - and further, that there innumerable ways in which they can be put to use:

§47: “The question … makes good sense if it is already established … which particular use of this word is in question. If it had been laid down… then the question … would have a clear sense - a clear use”.

Note here that use and sense are almost used as synonyms: to have a sense - to mean something - is to have a use (in a language-game…). The idea is that it is only once we have sorted out the particular grammar of our use of terms, that we can begin to make sense of the very question of the simple and the composite: getting the grammar right is a condition of making sense of the question, and subsequently, of being able to provide an answer. All this can be paraphrased by saying, as Witty kinda does, that one cannot make sense “outside a particular [language] game”: language-games act as conditions of sense.

§47 (Remark: Relation Between Language and World)

Here is where I think things actually get super interesting, from an epistemological point of view: if grammar is a condition of sense, and there are innumerable ways in which we can employ grammar(s), what exactly is the status of grammar (hence language and sense) itself? For it’s clear that grammar cannot be ‘read off’ the ‘thing itself’: the chess-board in all its black and white glory provides no definitive answer - cannot provide any definitive answer - as to how to parse what is simple and what is composite about it. The grammar of our languages(s) do not 'naturally mirror' the structure of the world (if it even makes sense to speak of a 'structure' of the world).

This, again, is because sense is function of our use of words. This is one way to understand Witty's objection to 'philosophy'. 'Philosophy', Witty thinks, tries to read sense directly off the world itself as though some kind of mirroring relation: it doesn't pay enough attention to the mediating role of grammar in conditioning sense (hence the closing remark of §47, which derides the 'philosophical question' by 'rejecting' it).

Now, there are a few directions and conclusions one can draw from this line of thought, but one I'd like to nominate is what I might call the relative autonomy of language (or, on the flipside, the indifference of the real (to language)): the act(s) of making sense are relative - and can only be relative - to the concerns and interests that we have as users of language - our forms-of-life, without which we would not make sense. Another way to put this is that meaning must be made, and not merely 'found': it involves an active process of construction, which is constrained by, but not entirely determined by, the reality of which it (sometimes) speaks. This needs to be made more precise, but I make these quick remarks as extrapolations from the text so far, to indicate at least the spirit in which I read these sections, if not the letter. Also worth keeping this in mind for the sections on aspect-seeing later on in the text. -

Ciaran

53I don't mean to derail the reading group, but having read the thread so far, I'd really like to know what people think Wittgenstein was trying to do by writing PI. It seems that a lot of posters are drawing conclusions as if they knew without first establishing why they've reached that conclusion.

Ciaran

53I don't mean to derail the reading group, but having read the thread so far, I'd really like to know what people think Wittgenstein was trying to do by writing PI. It seems that a lot of posters are drawing conclusions as if they knew without first establishing why they've reached that conclusion.

The analysis would be very different if a person were to approach the text assuming it to be a statement of 'the way things are' to if a person were to approach it as a normative statement of 'you should look at things this way (even though other ways are perfectly possible)'. In the former case, one can critique the text by arguing 'no, things are not that way, here's an example', but in the other, one would critique the text by saying 'looking at things this (other) way has the following use/value'.

A third way might be to simply presume that Wittgenstein must be coherent/useful to any intelligent reader at all points and so the exercise is to find that particular meaning in each sentence which is coherent to oneself, given all the other sentences, but this removes entirely the possibility of Wittgenstein simply not being coherent/useful at one point.

What seems to be happening on this thread is people taking one of the positions are arguing with people taking another as if they could actually resolve such differences.

I think any exercise such as this must first be explicit about its purpose. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI also didn't really understand your reference to primary elements being "self-refuting". — Luke

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI also didn't really understand your reference to primary elements being "self-refuting". — Luke

It's actually quite simple. The concept of "primary elements" is self-refuting, because these elements are said to be things which nothing can be said about. But this is to say something about them. You'll se that at 46, primary elements are defined as something which cannot be defined. My opinion is that by doing this, the philosophers who posit the existence of such things circumvent the law of identity. They posit the existence of a thing (primary element) which cannot be identified because it cannot be said to have any identifiable features.

The claim here, by Wittgenstein is that the primary element may have a name, but no other means of identification. It is identified by its name. So he points out at 48, if this is the case, then what is being identified, what is being given identity, is the name, rather than the element which the name is supposed to signify. The element itself has no identity because it is assumed to be primary, so nothing can be said about it, and all we are talking about now is the sign itself its, position in the sentence etc., the context and relations of the sign itself. The meaning of the name is given completely and absolutely by its context in use rather than by any reference to the thing named. You could say that we've removed correspondence as the basis of truth, and replaced it with coherency. (But remember, the basic premise ("primary elements") by which this was done is itself incoherent).

What Wittgenstein indicates at the end of 48, is the consequence of circumventing the law of identity in this way. There is now no way to distinguish an individual from a type, as what is being referred to by a name, unless one indicates that it is an individual or a type which is being spoken about. A primary element is represented by a name and nothing else. But all of the same type of primary element is represented by that same name. The designation of "primary element" prevents us from distinguishing one from the other, so they are all the same, just like all instances of the letter R are the same letter R, and if we want to distinguish them as individual instances of R's, we must indicate this. -

Sam26

3.2kMuch of this, including §47, is his way of arguing against his old way of thinking, and by extension arguing against how many philosophers knowingly or not think of meaning. As if simple, for example, can be reduced to some irreducible thing, giving us a one-to-one relationship between the word and the object (the referent). This is what Wittgenstein did in the Tractatus with his explanation of the smallest constituent part of a proposition (name), and its direct association with the smallest constituent part of a fact (object). As if sense can be derived from things in the world.

Sam26

3.2kMuch of this, including §47, is his way of arguing against his old way of thinking, and by extension arguing against how many philosophers knowingly or not think of meaning. As if simple, for example, can be reduced to some irreducible thing, giving us a one-to-one relationship between the word and the object (the referent). This is what Wittgenstein did in the Tractatus with his explanation of the smallest constituent part of a proposition (name), and its direct association with the smallest constituent part of a fact (object). As if sense can be derived from things in the world.

When Wittgenstein is talking about composite he is leading us in the direction of use, as opposed to some referent in the world (although there are times when the referent is obviously important). For example, "'Is what you see composite?' makes good sense if it is already established what kind of complexity-that is, which particular use of the word--is in question [my emphasis]." So, once we understand how we're using the term composite within a particular context of use, then "...we would have a clear sense--a clear use."

Note also when referring to how we might talk about the chessboard as being composite, that is, we might be tempted in some absolute sense to think that the chessboard is composite based on number of squares, colors, wood, etc. Thus, the point is that asking whether the board is simple or composite outside a language-game gets you nowhere. It's not what you have in mind that determines meaning. In other words, because you have in mind a particular association between composite and number of squares, colors, or bits of wood, that is not what gives meaning to the word composite. But if in a social context that's what we mean (which is based on use or grammar), then that use gives sense to the concept composite.

Streetlight you are correct to point out the relationship between all of this and epistemology. I think grammar should be seen as having the role of governing the moves within language-games, as opposed to the actual moves. An actual move may or may not conform to the rules of grammar. It follows from this that a correct move is in conformity with the grammatical rules. If we extend this analogy to epistemology, epistemology is simply a move in a language-game governed by the grammar in social contexts. -

Ciaran

53think Conant and Diamond are incorrect in the way they interpret parts of Wittgenstein — Sam26

Ciaran

53think Conant and Diamond are incorrect in the way they interpret parts of Wittgenstein — Sam26

What would measure a 'correct' interpretation? One which reflects what Wittgenstein actually meant? (how could we possibly know, and why would that matter?). One which reflects what Wittgenstein should have meant presuming his intention was to representent the way things actually are? One which is consistent with other things Wittgenstein said? (why would we presume to know what he meant by these further statements if the previous ones are ambiguous?). I just don't understand your use of the term 'incorrect' in this context and it seems to be heavily colouring the approach here (the use of the term, not the statement in which it is contained)

I guess it's possible some here might come to see what is going on in the PI, although I'm not too hopeful. — Banno

Same question. What measure are you proposing could be used to distinguish what 'is' going on in the PI from what some people simply 'think' is going on?

I think what you're doing here - slowly refining your views as L.W. forces them out of you - "It's experience...wait no, that's too broad, it's ways of seeing and acting, what no..." is what the book is aiming to get us to do as readers. — John Doe

Couldn't agree more. -

John Doe

200I don't mean to derail the reading group, but having read the thread so far, I'd really like to know what people think Wittgenstein was trying to do by writing PI. It seems that a lot of posters are drawing conclusions as if they knew without first establishing why they've reached that conclusion. — Ciaran

John Doe

200I don't mean to derail the reading group, but having read the thread so far, I'd really like to know what people think Wittgenstein was trying to do by writing PI. It seems that a lot of posters are drawing conclusions as if they knew without first establishing why they've reached that conclusion. — Ciaran

I really think we should wait until §§89-133 to start worrying about trying to work this stuff out, because as you point out, any discussion we have of his grand intentions right now will be slowly gliding across the ice into the horizon. We've got to wait for the rough ground of actual text.

One thing we can begin to discuss once we hit §89 is why order the book the way he does - why start by going to work in his manner of doing things only to then double back and begin to discuss why he's doing philosophical work in the manner that he is. It's a fascinating structure unique to Wittgenstein. It would be like Being and Time starting with two chapters of formal ontology before getting into the introduction and then back again to formal ontology. (Here I agree with @StreetlightX that we have to read this as indicative of philosophical intention and not mere haphazardness.)

So what getting to §89 will do is allow us not just to discuss big themes but also to glance backwards at §§1-88 and try to understand those sections in light of new developments in the dialectic.

(As to why I - likely others - are obnoxiously posting big picture stuff without getting in the weeds it's just because I lack the time to be a more diligent poster at the moment and @StreetlightX is doing a bloody fantastic job delving into the material with a sharp intellect at a great pace.)

I don't know why you would characterize my reply to Terrapin as shouting, maybe because of the force of the comment, I'm not sure. In fact, I tried to inject a bit of humor into the comment. — Sam26

Can we chalk this up to internet miscommunication (or my just being a lousy writer)? Perhaps a better way of putting the point I was hoping to make - cribbing the Conant & Diamond position which I take you to be not terribly well disposed to - is that (I think) what L.W. is doing in §§1-88 is trying to show Terrapin how and why he is wrong (or if you like trying to show young L.W. how and why he is wrong), and I think this is different from presenting a theory which offers a position which we can then argue contra Terrapin. If Terrapin doesn't agree to enter into the dialectic and take it seriously then I think from the perspective of what's going on in §§1-88, L.W. can't really offer him anything else. L.W. isn't offering the sort of thing we can shout at Terrapin, the way that a property dualist and physicalist do philosophy in the sort of way where they can shout back and forth at each other. -

Ciaran

53

Ciaran

53

I'm not sure I can agree with your analysis here. I understand entirely how the bigger question of Wittgenstein's intention cannot be deduced from the text until at least after §89, but I don't think there is much merit in the exegetical work prior to that.

The early points about the role of ostension, for example, seem to hinge entirely on an assumption that Wittgenstein was solely attempting to knock down some kind of straw man version of Augustine's argument which later sections make it clear (to me anyway) that he was not.

Unless this group is happy to agree on a particular interpretation of Wittgenstein's intent before beginning, then any exegesis of earlier statements without reference to both later ones, and a purpose to the critique/investigation in the first place are just going to get mired in pointless debate.

At the moment it seems to be a list of "things I reckon about Wittgenstein". We might as well discuss whether we like the font. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kHere is where I think things actually get super interesting, from an epistemological point of view: if grammar is a condition of sense, and there are innumerable ways in which we can employ grammar(s), what exactly is the status of grammar (hence language and sense) itself? For it’s clear that grammar cannot be ‘read off’ the ‘thing itself’: the chess-board in all its black and white glory provides no definitive answer - cannot provide any definitive answer - as to how to parse what is simple and what is composite about it. The grammar of our languages(s) do not 'naturally mirror' the structure of the world (if it even makes sense to speak of a 'structure' of the world). — StreetlightX

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kHere is where I think things actually get super interesting, from an epistemological point of view: if grammar is a condition of sense, and there are innumerable ways in which we can employ grammar(s), what exactly is the status of grammar (hence language and sense) itself? For it’s clear that grammar cannot be ‘read off’ the ‘thing itself’: the chess-board in all its black and white glory provides no definitive answer - cannot provide any definitive answer - as to how to parse what is simple and what is composite about it. The grammar of our languages(s) do not 'naturally mirror' the structure of the world (if it even makes sense to speak of a 'structure' of the world). — StreetlightX

Streetlight you are correct to point out the relationship between all of this and epistemology. I think grammar should be seen as having the role of governing the moves within language-games, as opposed to the actual moves. An actual move may or may not conform to the rules of grammar. It follows from this that a correct move is in conformity with the grammatical rules. If we extend this analogy to epistemology, epistemology is simply a move in a language-game governed by the grammar in social contexts. — Sam26

I don't see any mention of "grammar" as such, so unless this term "grammar" can be somehow related to what Wittgenstein is saying, I don't see how this discussion is relevant. He is still discussing the most simple aspects of language, ostensive definition (in relation to types), and naming (in relation to particulars). Grammar involves rules, and we have not gotten to the point where he discusses what learning a rule consists of. What I think, is that Witty has indicated that we learn all these language-games, ostensive definitions, and naming, without learning any grammar or rules at all. It's a matter of being conditioned in our activities, and creating habits. Whether or not these habits of language use which we develop, are good or bad, correct or incorrect, in relation to some grammar or rules, has not yet been discussed. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI'm not sure I can agree with your analysis here. I understand entirely how the bigger question of Wittgenstein's intention cannot be deduced from the text until at least after §89, but I don't think there is much merit in the exegetical work prior to that.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI'm not sure I can agree with your analysis here. I understand entirely how the bigger question of Wittgenstein's intention cannot be deduced from the text until at least after §89, but I don't think there is much merit in the exegetical work prior to that.

The early points about the role of ostension, for example, seem to hinge entirely on an assumption that Wittgenstein was solely attempting to knock down some kind of straw man version of Augustine's argument which later sections make it clear (to me anyway) that he was not. — Ciaran

I think you should chill out Claran, and not be so dismissive of the earlier parts of the text. All parts of a book are believed to be relevant to the story being told, by the author, or else they would not have been included in the book. What Witty is doing in the earlier parts is developing the issues, the problems which he believes ought to be addressed. If you just jump into the middle of the book you will not even recognize the problems which are being addressed and misunderstanding will be inevitable. . -

Sam26

3.2kA good interpretation of the text involves understanding Wittgenstein from the Notebooks (around 1914), which is his early thinking on meaning, all the way through to On Certainty. It doesn't mean you can't understand it without this background, but understanding the background gives you an advantage. Obviously there are going to be different interpretations, but that doesn't mean we can't get the gist of his thinking. It also doesn't mean that any interpretation is a good interpretation.

Sam26

3.2kA good interpretation of the text involves understanding Wittgenstein from the Notebooks (around 1914), which is his early thinking on meaning, all the way through to On Certainty. It doesn't mean you can't understand it without this background, but understanding the background gives you an advantage. Obviously there are going to be different interpretations, but that doesn't mean we can't get the gist of his thinking. It also doesn't mean that any interpretation is a good interpretation.

Even his Austrian background, viz., the culture in which he grew up is important to understanding the way Wittgenstein writes and thinks. Music played an important part in his family life growing up, and this too had an influence on the way he thought. So, the more you know about the man, the more you are able to understand his ideas. Reading letters he wrote to answer questions, looking at his style of architecture, examining his reasoning across a wide variety of his notes, etc, etc. All of these ideas are important to get a good understanding of his thinking.

There are obviously some spots in the texts that are very difficult to interpret. Even Wittgenstein looking back over some things he wrote wasn't able to always recall his line of thinking, so yes, there are things that are a matter of opinion. But I think as to the main thrust of what he's saying most people who have studied the texts can agree on many things, and other things are open to question.

When I give an interpretation of Wittgenstein I'm bringing in things that are not obvious to the text. For example, Wittgenstein wrote about grammar long before he wrote the PI, so his ideas of grammar are important to the text. It's also worth noting that there is a surface meaning to Wittgenstein, and there is a depth of meaning to Wittgenstein. Compare it to someone enjoying music in a very superficial way, as opposed to someone who has a very in-depth knowledge of music. You just aren't going to see or understand what they see and understand.

Streetlight has done a pretty good job for not having much of a background in Wittgenstein (if I understood his earlier comment correctly), but this is probably due to his philosophical background. If you can bring a wide array of thinking to bear on the subject, that too helps.

Some people just don't have the ability to think abstractly very well, and it's obvious who these people are when reading their posts. That's just the way it is. I'm not going to pretend that I'm good at basketball when I'm not, and if I do pretend, it will be obvious to those who know how to play, that I'm don't know what I'm doing. -

Ciaran

53

Ciaran

53

Not at all. If Wittgenstein had intended, in these first sections, to simply lay out the problems, and if those problems were simply the linguistic ones that have been listed thus far, then what on earth would have prevented him from simply listing then clearly enough to remove the ambiguity. He's writing a work of philosophy, not a bizarre combination of developmental psychology textbook and crossword puzzle. First year child development students are not handed PI as their main textbook on language acquisition and told that once they've studied Wittgenstein's entire biography they should be able to decipher enough clues to finally pass their exam. If facts about language acquisition and use are what you're all interested in I can point you in the direction of a dozen child psychology textbooks which are much more clearly written, widely agreed on and well-supported. People have literally travelled the world looking at every language they can find, they've spent lifetimes collating all the data, testing theories refining them in the light of experiments, why on earth would you shun this entire collection of well-researched data to decode the reckonings of an early twentieth century philosopher with no background in language.

If, however, you want to follow through the absolutely fascinating insights Wittgenstein has on the nature of enquiry, the pitfalls of certainty and the fragility of the conclusions drawn therefrom, then this is the book for you. -

Ciaran

53A good interpretation of the text involves understanding Wittgenstein from the Notebooks (around 1914), which is his early thinking on meaning, all the way through to On Certainty. — Sam26

Ciaran

53A good interpretation of the text involves understanding Wittgenstein from the Notebooks (around 1914), which is his early thinking on meaning, all the way through to On Certainty. — Sam26

Yet you've still failed to define what 'good' actually is in this context. How can you make assertions about what is 'good' and what is 'bad' without being able to define them? What is an interpretation trying to achieve, such that any could be good at it, and why would you rate that objective over any other?

Obviously there are going to be different interpretations, but that doesn't mean we can't get the gist of his thinking. — Sam26

I presume from your hints thus far that you've read a fairly wide selection of interpretations of the PI. I can't really see how, after having done so you could reach any conclusion other than that we absolutely cannot agree on the gist of his thinking. I'm struggling to see a single point of non-trivial agreement between, say Hacker at one end and Horwich at the other, or Baker in a completely different direction. If you're seeing some significant overlap I'm missing I'd be interested to hear it.

That's just the way it is. I'm not going to pretend that I'm good at basketball when I'm not, and if I do pretend, it will be obvious to those who know how to play, that I'm don't know what I'm doing. — Sam26

I'm afraid this is the sort of onanistic nonsense that really annoys me and I think spoils a perfectly interesting discussion such as this might otherwise be. It is obvious, to the uninformed observer, who is good at basketball because the object of the game is obviously to get the ball in the basket more often than your opponents. The player who achieves that (or helps his team to) is clearly good at basketball. No such equivalent exists for philosophy and trying to pretend that it does using some clandestine measure which cannot ever be actually tested is dishonest. -

Streetlight

9.1k§49

Streetlight

9.1k§49

I'm skipping §48 because it's fairly self-explanatory [no natural way to decide on a simple], but also because the later sections that return to it actually hold the more interesting discussions of the example that it offers. We'll take it up as those discussions crop up.

§49 (and §50!) return to the curious invocation of explanation in the Theaetetus passage quoted in §47. If we recall, there Socrates says that so-called primary elements cannot be explained, insofar as they themselves carry out explanatory work. Explanation is a one-way street, from simples, to composites. However, having 'grammatically relativized' (if we can call it that) what counts as a simple and a composite in §47 and §48, §49 now explores the consequences that this relativization has upon this apparent one-way street.

The consequences are as one would expect: Witty grants that if something counts as a simple in a particular use of langauge, then Socrates is right: the (grammatical) simple cannot be something that describes, insofar as it is only named (names do not describe). However, what are simples in one instance may be complexes in other instances: this is what Witty is getting at when he says that:

§49: "A sign “R” or “B”, etc., may sometimes be a word and sometimes a sentence. But whether it ‘is a word or a sentence’ depends on the situation in which it is uttered or written".

- where 'words' correspond to simples, and 'sentences', to composites. Two examples are given. The first in which someone is trying to describe the complex colored squares of §48 (in order to reconstruct it, say), wherein to speak of "R" is to have "R" function in an explanatory role (An imaginary conversation: Q: "What squares are in positions 1, 2, and 7?"; A: "R"). In this case, "R" describes - it plays an explanatory role. In the second case, one is trying to memorize what exactly is designated (named) by "R" in the first place ("That is 'R'"). In this case, R is not something that explains, but simply names.

One point of interest here is that §49 answers a question posed back in §26, where Witty writes that "One can call [naming] a preparation for the use of a word. But what is it a preparation for?". It's here, in §49, that Witty answers this question: "Naming is a preparation for describing".

As usual, Witty is once again paying close attention to the types of uses of words, without which one can fall into "philosophical superstition", as he calls it here. Such superstitions being, again, the confusion between kinds of uses of words. Here we can see a bit better why such confusions happen: precisely because the role that a word can play is reversible: in one case a simple, in one case a composite, in one case a name, in one case a description - all depending "on the situation in which it is uttered or written". -

Streetlight

9.1kGrammar involves rules, and we have not gotten to the point where he discusses what learning a rule consists of. — Metaphysician Undercover

Streetlight

9.1kGrammar involves rules, and we have not gotten to the point where he discusses what learning a rule consists of. — Metaphysician Undercover

At this point, Witty has nowhere linked grammar with rules (not saying there aren't any, but you're preempting, so your objection doesn't make sense).

Streetlight has done a pretty good job for not having much of a background in Wittgenstein (if I understood his earlier comment correctly), but this is probably due to his philosophical background. — Sam26

Cheers but I've been reading Wittgenstein on and off for years. Never quite in such depth, so this is a nice opportunity to hash out the PI in ways I've not done before.

StreetlightX is doing a bloody fantastic job delving into the material with a sharp intellect at a great pace — John Doe

Heh, I'm basically doing one subsection a night, and at this rate, it ought to take about two years or so lol. But hopefully not every section will demand commentary. -

Ciaran

53

Ciaran

53

Sorry, I know I'm new here and maybe I'm completely misunderstanding the sort of thing this forum is (if so, I apologise profoundly) but I really don't understand what you're aiming at here. You (and Sam) seem to be going through the statements one at a time writing what you reckon they mean and then dismissing any disagreement with your interpretation as being a result of the interlocutor's own (hopefully temporary) ignorance, and all will become clear later on.

Am I missing something major here, which those who've been here longer are aware of? Is it considered rude of us not to wait until you've finished your lecture before commenting? If this is supposed to be a thread where one or two people who've read the book guide a larger number who haven't through their own personal interpretation then I'm absolutely fine with that, I just want to understand how the thread works rather than waste my time (and annoying everybody) by getting involved in a way that is not generally acceptable. -

Ciaran

53

Ciaran

53

Reading the PI is not a collective activity, discussing it is. Its the nature and conduct of the second part I was enquiring about, not the first.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- My latest post was deleted from the 'Philosophical Investigations, reading it together' discussion?

- Philosophical Investigations, reading group?

- How Important is Reading to the Philosophical Mind? Literacy and education discussion.

- How important is our reading as the foundation for philosophical explorations?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum