-

Janus

18kYou are probably right that I can become a little verbally aggressive when it becomes obvious to me that the person I am supposed to be discussing with refuses to address my arguments by either distorting them, dismissively labeling them as examples of some ism or other, or simply ignores them. I said you were "full of shit" only once when you claimed to have addressed what I said and that claim was patently untrue. I have probably accused you of intellectual dishonesty a few times for the same reason.

Janus

18kYou are probably right that I can become a little verbally aggressive when it becomes obvious to me that the person I am supposed to be discussing with refuses to address my arguments by either distorting them, dismissively labeling them as examples of some ism or other, or simply ignores them. I said you were "full of shit" only once when you claimed to have addressed what I said and that claim was patently untrue. I have probably accused you of intellectual dishonesty a few times for the same reason.

These reactions that express annoyance are not ideal...I acknowledge that, but they have been prompted by frustration. You cannot seriously claim that I don't understand your arguments...in fact you know very well that I do understand them. If I didn't understand them I would ask for clarification, and this is usually not necessary in your case because your writing is clear enough. It is intellectually dishonest to tell someone that they don't understand what you have written if they have not asked for further explanation and if you are not prepared to cite what they have said in response and clearly explain how it constitutes a misunderstanding as opposed to a mere disagreement.

I see you often use this tactic of claiming that your interlocutor simply does not understand in your discussions with others. I will continue to critique what you write if I think it is inconsistent or dogmatic. I reserve the right to call out dogmatism when I see it, and I will always give a clear and sufficient explanation as to why I think it is dogmatic, and then the ball is in your court to defend your claims against the charge of dogmatism by offering cogent arguments as to why it should not be considered to be so. Whether you respond or not is up to you. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe problem is that in order for our own categories and intuition to 'ordain' the empirical world, I believe you need to posit some structure onto the noumenal and this suggests that we do have some knowledge of the noumenal, — boundless

Wayfarer

26.2kThe problem is that in order for our own categories and intuition to 'ordain' the empirical world, I believe you need to posit some structure onto the noumenal and this suggests that we do have some knowledge of the noumenal, — boundless

As you've mentioned Michel Bitbol in the past I did a bit of research on Bitbol's comparison of Kant and Neils Bohr's approach to quantum physics. Bitbol applies Kant's transcendental idealism to quantum mechanics, arguing that quantum phenomena reflect the fundamental limits and structure of human knowledge rather than revealing the intrinsic nature of reality itself. So he pushes back on the suggestion that physics is providing 'some knowledge of the noumenal'.

In this framework, quantum indeterminacy, complementarity, and measurement problems aren't puzzling features of physical reality that need to be accounted for, but are, rather, inevitable consequences of the necessary forms of knowledge. Just as Kant argued that space, time, and causality are forms that structure experience, rather than features of the in-itself, Bitbol suggests that quantum mechanical concepts like wave functions and observables are epistemological structures that are basic to the way experience is organised, rather than descriptions of what exists independently of observation. 'According to Bohr, ‘all knowledge presents itself within a conceptual framework’, where, by ‘a conceptual framework’, Bohr means ‘an unambiguous logical representation of relations between experiences' ('Bohr's Complementarity and Kant's Epistemology').

This perspective reframes the measurement problem: instead of asking 'what does wave function collapse mean?' or 'is the wave function physically real?' we ask 'what must be the case about the structure of experience for measurement to be a coherent concept?'" The apparent strangeness of quantum mechanics becomes less mysterious when viewed as reflecting the necessary structure of empirical knowledge rather than bizarre features of microscopic reality. Bitbol argues this dissolves many traditional quantum interpretational puzzles by recognizing them as category mistakes - attempts to apply concepts beyond their proper epistemological domain (i.e. extending empirical concepts beyond their scope). Rather than seeking to explain quantum mechanics in terms of hidden variables or many worlds, we should understand it as revealing the transcendental conditions that are the necessary conditions for knowledge.

So in this approach, Neils Bohr's philosophy of physics, at least, is presented as being compatible with the Kantian framework. He's developed these ideas in many papers that can be found on his Academia profile.

So again this lends support to some basic aspects of Kant's (as distinct from Berkeley's) form of idealism. The idea that 'the structure of possible experience constrains what can count as empirical knowledge' has had considerable consequences in many schools of thought beyond quantum mechanics. As for Berkeley, though, these kinds of developments provide a partial vindication - by bringing the observer back to the act of observation ;-) -

Apustimelogist

946aren't puzzling features of physical reality that need to be accounted for — Wayfarer

Apustimelogist

946aren't puzzling features of physical reality that need to be accounted for — Wayfarer

But they are. They are obviously physical events happening out in reality. If you do a double slit experiment and close or measure one of the slits, it will physically change the results you see of where particles are hitting the screen at the end of their journey.

Edit: And to be clear, by "physically changes the results", I just mean the system behaves differently in different situations.

Spelling/Grammar corrections. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThey are obviously physical events happening out in reality — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kThey are obviously physical events happening out in reality — Apustimelogist

Closing one slit is physical, But how is the act of measurement physical? Isn't that the whole measurement problem in a nutshell? -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

Because registering a measurement result requires the measuring device to physically interact with the system you are measuring. The stronger the measurement interaction (i.e. correlation), the stronger the disturbance. Closing the slit is arguably no less mysterious either because its not obvious to most why the closing the slit would change the behavior either.

The measurement problem depends on your interpretation on QM. But the physical effect measurements have is regardless of interpretation. Saying the wavefunction isn't real can be a solution to the measurement problem but the solution or interpretation would still have to account for how measurements to have a disturbing physical effect. -

Wayfarer

26.2kBecause registering a measurement result requires the measuring device to physically interact with the system you are measuring. — Apustimelogist

Wayfarer

26.2kBecause registering a measurement result requires the measuring device to physically interact with the system you are measuring. — Apustimelogist

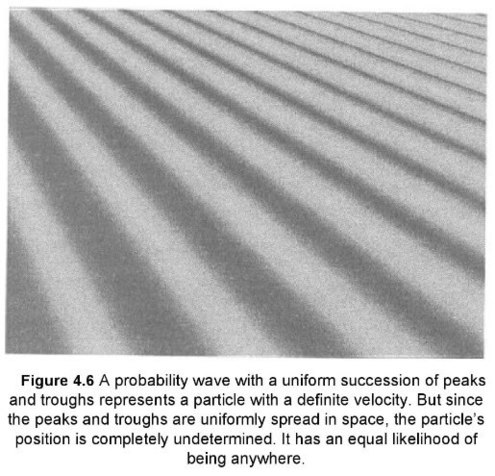

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6.

Since the peaks are all uniformly moving to the right, you might guess that this wave describes a particle moving with the velocity of the wave peaks; experiments confirm that supposition. But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it. — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

the solution or interpretation would still have to account for how measurements to have a disturbing physical effect. — Apustimelogist

The Kantian response would be: why assume measurement must be understood as a "disturbing physical effect" at all? This assumes measurement is fundamentally about one physical system causally interacting with another physical system. The "disturbance" language already smuggles in a particular metaphysical picture - that there are definite physical properties in existence that are disturbed by measurement. But the point is, the object, so called, has no definite or determinate existence prior to its being measured (hence 'wave-particle duality'). -

RussellA

2.7kWhat's a "fact"? It's apparently not something existing in the world, so what is the correspondence? It seems to be a correspondence between two "things" that are both within your mind, and therefore circular. — Relativist

RussellA

2.7kWhat's a "fact"? It's apparently not something existing in the world, so what is the correspondence? It seems to be a correspondence between two "things" that are both within your mind, and therefore circular. — Relativist

A public language exists as a fact in the world, therefore the word "chair" exists as a fact in the world.

The correspondence is between the concept of a chair in my mind and the word "chair" that exists as a fact in the world. -

boundless

760So again this lends support to some basic aspects of Kant's (as distinct from Berkeley's) form of idealism. The idea that 'the structure of possible experience constrains what can count as empirical knowledge' has had considerable consequences in many schools of thought beyond quantum mechanics. As for Berkeley, though, these kinds of developments provide a partial vindication - by bringing the observer back to the act of observation ;-) — Wayfarer

boundless

760So again this lends support to some basic aspects of Kant's (as distinct from Berkeley's) form of idealism. The idea that 'the structure of possible experience constrains what can count as empirical knowledge' has had considerable consequences in many schools of thought beyond quantum mechanics. As for Berkeley, though, these kinds of developments provide a partial vindication - by bringing the observer back to the act of observation ;-) — Wayfarer

Thanks for the Bitbol reminder! In any case, as I said, I believe the great merit of epistemic idealism (of whatever form) is to remind us that the mind has an active role in give an 'order' to what we are experiencing. In other words, we can't neglect the role that the 'constraints of possible experiences' have on what we actually experience.

Still, I honestly think that epistemic idealists (like Bitbol, Kant etc) do go too far.

For instance, in order to avoid to imply that we create the 'empirical world' out of pure thought, Kant had to concede that there is a reality beyond of experience that provide our mind the 'matter', to use Arisostotelian language, for then 'building up' the 'forms' via the faculties of sensibility, intellect and so on. However, it seems to me that if the 'reality beyond/before phenomena' was structureless, it would not possible for us to give it a 'form'.

Personally, I think that D'Espagnat provides a good correction of epistemic idealism. The active role of mind is accepted almost to the degree of Kant etc but, at the same time, D'Espagnat's view accepts that the 'reality beyond/before phenomena' has its own structure that is 'veiled' for us (and by studiying the 'empirical world' we can know 'as through a glass darkly' to borrow again, out of context, St. Paul's famous phrase).

So, yeah, I guess that for me Kant's and Bitbol's approach is incomplete rather than being 'misguided', so to speak. -

boundless

760But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

boundless

760But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

There are also Interaction-free measurement, which IIRC do not seem to require a direct interaction between the system and the measurement apparatus and yet they do bring an 'update' to the wavefunction.

To make an example: if you emit a particle and a detector detects it, you have a normal measurement, which involves an interaction, and you now know the position of the particle. If you, however, activate the detector and it doesn't detect the particle, you know where the particle is not. This suggests that you was able to 'update' the wavefunction of the particle in question without interacting with it.

If I am not mistaken, in de Broglie-Bohm's view, this involves some kind of nonlocal interaction between the detector and the particle. A QBist would say that no interaction occurred and the 'negative result' update our 'degree of belief' of where the particle is.

In any case, the so called 'interaction-free measurements' are ways to get new information without getting 'positive' results. -

RussellA

2.7kThe claim "esse est percipi", to perceive is defined and explained clearly in many of the philosophers' passages. Berkeley's is no different -- to perceive is to use the 5 senses and of course the understanding of this perception. — L'éléphant

RussellA

2.7kThe claim "esse est percipi", to perceive is defined and explained clearly in many of the philosophers' passages. Berkeley's is no different -- to perceive is to use the 5 senses and of course the understanding of this perception. — L'éléphant

"Esse est percipi" may be translated as "to be is to be perceived".

We both perceive through our sense of vision that Mary is wearing a yellow jacket.

Therefore for Berkeley, in the mind of God, Mary is wearing a yellow jacket.

However, I may perceive Mary is bored because she is wearing bright clothes and you may perceive that Mary is not bored precisely because she is wearing bright clothes.

If perception refers to understanding, the situation becomes very unclear. How can anyone know what is in the mind of God if everyone's perceived understanding of the same situation is probably different. How can anyone ever know Mary's true state of being.

Mary's "to be" can never be known if "is to be perceived" means perceived in the understanding.

===============================================================================

I think you must be conflating physicalism with "matter" which we call substance that is independent of tangible things and perceptible qualities. — L'éléphant

Some say that "Physicalism" is interchangeable with "Materialism".

Materialists held that everything was matter, an inert, senseless substance.

But Physicalists point out that not everything is matter, in that a force such as gravity is physical but not material in the traditional sense.

Both Materialists and Physicalist believe that there are things in the world existing independently of any observation by either human or god.

From SEP - Physicalism

Physicalism is sometimes known as ‘materialism’. Indeed, on one strand to contemporary usage, the terms ‘physicalism’ and ‘materialism’ are interchangeable. But the two terms have very different histories.

As the name suggests, materialists historically held that everything was matter — where matter was conceived as “an inert, senseless substance, in which extension, figure, and motion do actually subsist”

But physics itself has shown that not everything is matter in this sense; for example, forces such as gravity are physical but it is not clear that they are material in the traditional sense

I will adopt the policy of using both terms interchangeably. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kTables and chairs may not exist in the world as physical things, but "tables" and "chairs" do exist in the world as physical things, as physical words. — RussellA

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kTables and chairs may not exist in the world as physical things, but "tables" and "chairs" do exist in the world as physical things, as physical words. — RussellA

But the issue is, how do these things, words in this example, exist in that medium between you and me? Is the concept of "matter" required to explain that medium?

Scenario one. A white ball hits a red ball, and the red ball moves.

Scenario two. A white ball almost hits a red ball. I put my hand between them and the red ball doesn't move.

Both scenarios are consistent with being in a deterministic world.

In scenario one, there is the conservation of momentum.

In scenario two, living in a deterministic world, I had no choice but to put my hand between the white and red ball.

In both scenarios, there is a necessary and deterministic continuity from past to present. — RussellA

You can make that conclusion, but it displays a gap in understanding. What is the source of that freely willed act?

To say "I had no choice but to put my hand between the white and red ball" is not a good answer. It denies the usefulness of deliberation, which is not a good thing to do.

So I believe that determinism is a cop out, a refusal to address a huge aspect of reality.

For example, consider two identical clocks both set at 1pm that slowly move apart. The times shown on their clock faces will remain the same, not because of some external connection between them, but because Clock A is identical to itself, clock B is identical to itself and clock A is identical to clock B. — RussellA

The law of identity denies the possibility that two distinct clocks, named as A and B, are identical. So your example, although referring to the law of identity, really violates it.

I don't believe so. Newton like others of his period was deist. Deists believed that God 'set the world in motion' but that thereafter it ran by the laws that Newton discovered. Hence LaPlace's declaration (LaPlace being 'France's Newton'), when asked if there were a place for the Divine Intellect in his theory, that 'I have no need of that hypothesis'. — Wayfarer

I've read a lot of Newton's material, and I think you misunderstand him. He clearly believed his laws of motion to be descriptive. He did not believe that he had discovered God-created laws which govern the world. This is very evident in his work, especially on optics. He was a very good scientist, looking to describe the natural world, and very respectful of the fact that anything he produced could be a mistake.

Therefore he clearly did not believe himself to be discovering divine laws, which would allow no possibility of mistake. Or would you think that there is an infinite number of laws out there to be discovered, and one set is "The Divine Set". If so, how would one distinguish "The Divine Set" of laws from the infinite other possibilities, when searching for these divine laws.

I don't understand your reference to LaPlace. It seems self-contradicting. If Newton believed that he had discovered divine laws, then clearly there is a requirement for Divine Intellect as creator of those laws. But this is not what scientists do. They do not seek to discover divine laws, they seek to describe the world. That is the point of the scientific method, a method to ensure what is known as "objective" descriptions. The scientific method gives no direction about prospecting for divine laws. That's more of a metaphysical interpretation of what the scientist does. A very faulty interpretation, I might add. -

RussellA

2.7kBut the issue is, how do these things, words in this example, exist in that medium between you and me? Is the concept of "matter" required to explain that medium? — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kBut the issue is, how do these things, words in this example, exist in that medium between you and me? Is the concept of "matter" required to explain that medium? — Metaphysician Undercover

Words must physically exist in some form in the physical space between where you exist and where I exist, otherwise we would not be able to exchange ideas.

===============================================================================

To say "I had no choice but to put my hand between the white and red ball" is not a good answer. It denies the usefulness of deliberation, which is not a good thing to do. — Metaphysician Undercover

In a deterministic world, you had no choice but to put your hand between the white and red ball.

Deliberation is part of a process that is determined in a deterministic world.

===============================================================================

The law of identity denies the possibility that two distinct clocks, named as A and B, are identical. So your example, although referring to the law of identity, really violates it. — Metaphysician Undercover

My main point is that the clocks A and B will continue to show the same time, not because of any external connection between them, but because of their particular internal structures. IE, there need not be a universal time in order for these two clocks to show the same time. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

The way to view it is that in quantum mechanics the statistics of complementary variables have to abide by uncertainty relations in all physical situations. If you change the physical situation in a way that allows it to behave differently, it still has to obey those uncertainty relations.

Measurements are physical interactions and they are designed to induce sharp correlations with the measured system which have to obey uncertainty relations. This is why disturbance occurs. Its not because measurements are special; the disturbing properties of measurement are just a special case of disturbing propeties that can occur for any physical interaction.

This assumes measurement is fundamentally about one physical system causally interacting with another physical system. — Wayfarer

Its hard to interpret this differently. You have a double slit scenario and you throw particles through the slits; they will form an interference pattern on the screen. Now you insert the measuring device in the scenario; the particles no longer show fringes but clumps. This is an unambiguous physical change in the behavior of a physical system.

The "disturbance" language already smuggles in a particular metaphysical picture - that there are definite physical properties in existence that are disturbed by measurement. — Wayfarer

But you can prepare systems to have definite properties and then disturb them. You can prepare light so that it has a specific, definite polarization in one direction; you can then out it through polarizers which will then evince disturbance of the systens properties.

In any case, the so called 'interaction-free measurements' are ways to get new information without getting 'positive' results. — boundless

But "interaction-free measurements" work because there is a physical change in the system behavior due to a change in the experimental context, analogous to closing a slit in the double slit experiment. -

Mww

5.4kI guess that for me Kant's (…) approach is incomplete…. — boundless

Mww

5.4kI guess that for me Kant's (…) approach is incomplete…. — boundless

With respect to D'Espagnat’s thesis on, as you say, “…‘reality beyond/before phenomena' has its own structure that is 'veiled' for us (and by studying the 'empirical world' we can know 'as through a glass darkly')…”, the only way it would work, that is, to have sufficient explanatory power, would be to re-define the structure of transcendental arguments beyond the Kantian norm. Otherwise, there is only contradiction.

Kant’s philosophy regarding empirical knowledge is complete within itself; anyone can call it incomplete when taken beyond the measure by which its completeness was already given.

Better to say D’Espagnat developed a more complete epistemic idealist theory grounded in transcendental realism, than to say Kant developed a less complete epistemic theory because it wasn’t. -

sime

1.2kA classical analogy for interaction free measurements, as in the quantum Zeno Elitzur–Vaidman_bomb_tester, can be given in terms of my impulsive niece making T tours of a shopping mall in order to decide what she'd like me to buy her for her birthday.

sime

1.2kA classical analogy for interaction free measurements, as in the quantum Zeno Elitzur–Vaidman_bomb_tester, can be given in terms of my impulsive niece making T tours of a shopping mall in order to decide what she'd like me to buy her for her birthday.

Suppose that she has my credit card for some reason (oops my mistake), and I take her to a shopping mall so that she can find something she would like for her birthday. If she finds what she wants, then on each iteration t of the mall there is a chance that she will succumb to temptation and use my credit card to buy the item for herself there and then, resulting in her feeling immediate guilt and confessing, such that we leave the mall there and then (outcome |1>, bomb exploded). If she is good and manages to resist temptation for T iterations, then she tells me what she would like for her birthday and we both leave happy (outcome |0>, bomb live). Else after T iterations she doesn't find anything she would like and we both leave the mall disappointed (outcome |1>, bomb dud).

- Whereas my niece and my credit card have a definite location, my money does not, and neither does her gift until as and when the credit card is used.

- Interaction free measurements aren't non-classical unless Bell's inequalities/Quantum contextuality are involved (and which are not involved in the above analogy). -

Janus

18kHowever, it seems to me that if the 'reality beyond/before phenomena' was structureless, it would not possible for us to give it a 'form'. — boundless

Janus

18kHowever, it seems to me that if the 'reality beyond/before phenomena' was structureless, it would not possible for us to give it a 'form'. — boundless

I made the same point myself earlier in the thread but it received no response―which is probably understandable.

Not sufficient to explain the commonality of experience. That's why Kant says there are things in themselves which appear to us as phenomena. Schopenhauer disagreed and claimed there cannot be things in themselves if there is no space and time (both of which are necessary for differentiation) except in individual minds. To posit an undifferentiated, unstructured thing in itself that gives rise to an unimaginably complex world of things on a vast range of scales is, to say the least, illogical. — Janus

Kant may have "gone too far" as you say―it depends on how you read him. There are realist interpretations of Kant―that is there are scholars who interpret him as thinking that things in themselves are mind-independently real, but unknowable as they are in themselves (and that by mere definition) and knowable only as they appear to us.

Anti-realists, anti-materialists, anti-physicalists have a vested interest in denying the reality of things in themselves, because to allow them would be to admit that consciousness is not fundamental, and, very often it seems, for religious or spiritual reasons they want to believe that consciousness is fundamental, especially if they don't want to accept the Abrahamic god. One can, without inconsistency, accept the Abrahamic god and be a realist about mind-independent existents. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWords must physically exist in some form in the physical space between where you exist and where I exist, otherwise we would not be able to exchange ideas. — RussellA

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWords must physically exist in some form in the physical space between where you exist and where I exist, otherwise we would not be able to exchange ideas. — RussellA

Of course, but the question is how. Do they consist of matter, or do they exist in some other way?

Deliberation is part of a process that is determined in a deterministic world. — RussellA

Sure, but if I have no choice as to whether or not I do something, isn't it illogical for me to deliberate? I mean deliberation requires a lot of effort, which is stressful, often difficult, annoying, and even frustrating. If it is something which is determined, by a deterministic world, then I'll just forget about making that stressful annoying effort. I'll just go with the flow, and let the deterministic world force deliberation upon me, if and when it must. If I believed in determinism I would not take up that painful and hypocritical position of deliberating voluntarily. Why would anyone, if they truly believed in determinism?

My main point is that the clocks A and B will continue to show the same time, not because of any external connection between them, but because of their particular internal structures. IE, there need not be a universal time in order for these two clocks to show the same time. — RussellA

I don't know about that, relativity theory says they won't necessarily show the same time, depending on external conditions. -

RussellA

2.7kOf course, but the question is how. Do they consist of matter, or do they exist in some other way? — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kOf course, but the question is how. Do they consist of matter, or do they exist in some other way? — Metaphysician Undercover

Words exist in a mind-independent world in two ways, in the same way that 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 exists in two ways.

They exist as physical matter, whether as electrons or the pixels 0 and 1, and they exist as spatial and temporal relations between these electrons or pixels.

Your mind perceives not only the pixels on your screen but also the spatial relations between these pixels on your screen

Even when not looking at your screen, these pixels and spatial relations between them exist on your screen.

===============================================================================

If it is something which is determined, by a deterministic world, then I'll just forget about making that stressful annoying effort. — Metaphysician Undercover

To forget about making an effort assumes free will. In a deterministic world, your decision to forget about making an effort has already been determined. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThey exist as physical matter, whether as electrons or the pixels 0 and 1, and they exist as spatial and temporal relations between these electrons or pixels. — RussellA

Wayfarer

26.2kThey exist as physical matter, whether as electrons or the pixels 0 and 1, and they exist as spatial and temporal relations between these electrons or pixels. — RussellA

Are you familiar with the modern philosophical expression 'the space of reasons?' The "space of reasons" is a concept developed by philosopher Wilfrid Sellars. It refers to the domain of rational thought where beliefs, judgments, and actions can be justified through reasons and evidence.

The key idea is that there's a fundamental distinction between two realms: the "space of reasons" (where we give and ask for justifications, make inferences, and engage in rational discourse) and the "space of causes" (the physical world of natural laws and causal mechanisms). When we're in the space of reasons, we're not just describing what happens, but explaining why something is justified or makes sense.

For example, if you believe it's going to rain, you're in the space of reasons when you point to dark clouds as your justification - not just as a physical cause of your belief, but as evidence that makes your belief rational. The space of reasons is essentially the arena of human rationality where we can evaluate whether our thoughts and actions are warranted.

Do you see the distinction being made between reasons and causes? -

RussellA

2.7kDo you see the distinction being made between reasons and causes? — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.7kDo you see the distinction being made between reasons and causes? — Wayfarer

I put my hand between the white ball and the red ball. If I have free will, then I have a reason. In determinism, there is a cause.

From Britannica - Reason

Reason, in philosophy, the faculty or process of drawing logical inferences.

Logic in a narrow sense is equivalent to deductive logic. By definition, such reasoning cannot produce any information (in the form of a conclusion) that is not already contained in the premises.

However, sooner or later, reason breaks down, as premises are assumed to be true, not proved to be true.

When asked "why did you put your hand between the white ball and the red ball?", at the end of the day it comes down to "no reason, because I wanted to". -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

A good account. Thanks.

I hope this is of some interest.

Berkeley has the problem that afflicts many philosophers who want to deny the existence of something. The kinds of thing that philosophers are interested in are such that to deny their existence seems to be to deny the existence of things whose existence is blindingly obvious. Wittgenstein’s private language argument is a case in point, and recent philosophy has been much concerned about Dennett and others who seem to claim that our perceptions are all illusions.I do not argue against the existence of any one thing that we can apprehend, either by sense or reflection. That the things I see with my eyes and touch with my hands do exist, really exist, I make not the least question. The only thing whose existence we deny is that which philosophers call ‘matter’ or ‘corporeal substance’. — Berkeley - Treatise 35

Berkeley here is claiming that this is an entirely technical debate and has no effect on common sense. No wonder his theory got tagged as “immaterialism”, which also means something that doesn’t matter. But he doesn’t mean that it does not affect anything of real importance. He thinks that to eliminate the concept of matter is to remove an important cause of atheism, scepticism and even socianism – and who could not think that those are important issues?

One of the reasons that it is so hard to discern what Berkeley is claiming is that he goes back on things that he has said. For example, he proposes that to exist is to be perceived (I don’t know what arguments he has to back up that claim, but let that pass). But he realizes later that in every one of his perceptions, there is an element that is not perceived – himself. He allows, therefore, that I am in fact able to infer my own existence from my perceptions. He denies that I can have an idea of my own, or any other, mind. I know them, he says, by their effects – not by an idea of them, but a “notion” of them.

(I think he means by “notion” something that we know, not directly by perception, but indirectly, by reflection and inference. I’m not clear how this related to “esse est percipi”.)

He indignantly rejects the inference that matter exists, on the ground that it is an unknowable substance underlying and causing our experience. Actually, the deeper reason is that he thinks that matter is inert and that inert things are incapable of causing anything. It’s a neat twist, I have to admit, but it is also a re-thinking and redefining of the concept of matter. He is in fact talking past all his opponents.

This is is final move. So what it all comes to is that incorporeal active substance or spirit replaces the inert substance matter.I do not argue against the existence of any one thing that we can apprehend, either by sense or reflection. That the things I see with my eyes and touch with my hands do exist, really exist, I make not the least question. The only thing whose existence we deny is that which philosophers call ‘matter’ or ‘corporeal substance’. — Berkeley Treatise 26

It is true that the idealism of Bradley, Green and Bosanquet fell out of favour. That was in the Hegelian tradition. But the sense-data theory of Ayer and the phenomenalism of Carnap was very much in the tradition of Berkeley.However, by the early 20th century, philosophical idealism fell out of favor — particularly in the English-speaking world -

Wayfarer

26.2kI hope this is of some interest. — Ludwig V

Wayfarer

26.2kI hope this is of some interest. — Ludwig V

Indeed, I did also mention that, to dispel the idea that Berkeley dismissed sensible objects as mere phantasms.

One of the reasons that it is so hard to discern what Berkeley is claiming is that he goes back on things that he has said. For example, he proposes that to exist is to be perceived (I don’t know what arguments he has to back up that claim, but let that pass). — Ludwig V

Notice that he means sensible things - actually, I prefer the term 'sense-able', as 'sensible' has a different meaning in everyday speech. So he's saying objects of perception exist in perception - if not yours or mine, then the Divine Intellect, which holds them in existence. You probably know this limerick but as it's a Berkeley thread, it's always worth repeating:

There once was a man who said “God

Must think it exceedingly odd

If he finds that this tree

Continues to be

When there’s no one about in the Quad.”

Dear Sir,

Your astonishment’s odd.

I am always about in the Quad.

And that’s why the tree

Will continue to be

Since observed by…

Yours faithfully,

God

What Berkeley denies is the existence of corporeal substance, where 'substance' is used in the philosophical, rather than day-to-day, sense: the bearer of predicates, that which underlies appearances. He claims that is an abstraction - which is a point I hope I made sufficiently clear in the OP.

As for the mind not being able to percieve itself, this is something I often repeat, because I believe it's manifestly true. The relevant passages in the Principles of Human Knowledge:

But besides all that endless variety of ideas or objects of knowledge, there is likewise something which knows or perceives them, and exercises divers operations, as willing, imagining, remembering about them. This perceiving, active being is what I call mind, spirit, soul, or myself. By which words I do not denote any one of my ideas, but a thing entirely distinct from them, wherein they exist, or, which is the same thing, whereby they are perceived; for the existence of an idea consists in being perceived. ...

And later (§89):

“From what has been said it is plain there is not any other substance than spirit, or that which perceives. But for the fuller understanding of this, it must be considered that we do not see spirits … we have no ideas of them. Hence it is plain we cannot know or perceive spirits, as we do other things; but we have some notion of our own minds, of our own being; and that we can have no idea of any spirit is evident, since it is not an idea. Spirits are things altogether of a different sort from ideas.”

Note again that 'substance' here is from the Latin 'substantia', originating with the Greek 'ousia'. So it could equally be said 'there is not any other kind of being than spirit', which sounds to me less odd than 'substance' in the context.

the sense-data theory of Ayer and the phenomenalism of Carnap was very much in the tradition of Berkeley — Ludwig V

Only insofar as all were empiricists - 'all knowledge from experience'. IN other respects, chalk and cheese. Ayer and Carnap would have found Berkeley's talk of spirit otiose, to use one of their preferred words. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWords exist in a mind-independent world in two ways, in the same way that 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 exists in two ways.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWords exist in a mind-independent world in two ways, in the same way that 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 exists in two ways.

They exist as physical matter, whether as electrons or the pixels 0 and 1, and they exist as spatial and temporal relations between these electrons or pixels.

Your mind perceives not only the pixels on your screen but also the spatial relations between these pixels on your screen

Even when not looking at your screen, these pixels and spatial relations between them exist on your screen. — RussellA

Let's consider "pixels". You say that there are pixels which have spatial relations between them. But a pixel, which is normally thought of as a fundamental element of a picture, is actually composed of smaller parts which have spatial relations. And if we think of "physical matter" in this way, we get the appearance of an infinite regress, because each time we find what looks to be the fundamental elements, we then find out that they can be broken down into further spatial relations.

There is a strong argument for the ideality of spatial relations. We use mathematical tools of numbers and geometry, which are concepts, and we try to represent the supposed independent reality with those concepts. Intuition tells us that reality cannot exist solely of spatial relations, there must be some material in these relations, so to the infinite regress may be avoided with the positing of fundamental particles, "matter". However, nature throws a curve-ball, and complicates everything with the fact that time is passing, and spatial relations are continually changing. Now, "spatial relations" may be replaced by "spatial activity".

So, the primary intuition was to believe that there must be some form of foundational matter, substance which exists in spatial relations that are expressed mathematically. However, the passage of time necessitates that we understand this as activity, and the supposed foundational matter appears so rapid, that it makes the activity of any proposed fundamental matter unintelligible.

Now we have a second possible intuition. Perhaps there is no fundamental matter at all, and the activity is simply the activity of space. What was represented as particles of matter existing in 'changing spatial relations', may actually be just 'changing spatial relations' without any real particles of matter. These 'changing spatial relations' are what is known as the field, and the wavefunction.

The developing problem, is that as described above, the "spatial relations" are ideal, conceptual mathematics and geometry. And, unless there is some form of substance existing, in these relations, we lose any form of physical realism, relying solely on Platonic realism, to understand these ideal features, fields and wave functions, as real. This is why space itself needs to be understood as real active substance. Traditionally, space was known to be an aether, and the waves of electromagnetism was understood as the activity of that aether. And this is what is missing from our current understanding.

We have removed the substance, fundamental matter, which is proposed as existing in active spatial relations, to understand the activity simply as active spatial relations. The supposed matter, particles, simply cannot exist in the contradictory relations represented by the mathematics. So the accurate representation is just mathematical relations. However, unless the substance of space is identified, and properly observed, all we have is a Platonic idealism within which these mathematical relations are the substance of the universe.

To forget about making an effort assumes free will. In a deterministic world, your decision to forget about making an effort has already been determined. — RussellA

That looks like an infinite regress in the making. You are telling me to forget about forgetting about making an effort, because whether or not you will forget about it has already been predetermined.

In effect, you are telling me to forget about having any freedom, because you don't have any. That might work on some people, but you can't pull the wool over my eyes. -

Outlander

3.2kIn effect, you are telling me to forget about having any freedom, because you don't have any. That might work on some people, but you can't pull the wool over my eyes. — Metaphysician Undercover

Outlander

3.2kIn effect, you are telling me to forget about having any freedom, because you don't have any. That might work on some people, but you can't pull the wool over my eyes. — Metaphysician Undercover

See this is interesting because, let us, say, take Pascel's "demon" (or whatever) where one knows what men cannot know. The Universe is, according to theory, constantly expanding, and as a result (or many results of said result) will, allegedly, succumb to "Heat Death."

This is a widely accepted scientific theory. Now, if we assume the idea or existence of this being or rather mindset of a being that either exists or can exist in another universe where the so-called "laws of physics" are different, even slightly. This fate can be skirted. At least in theory, and so, by definition, enters the territory of falsehood, despite it being a transient truth of one locale. No different than the rain forest is wet and the desert is dry. Wet and dry never become distinct concepts, simply our idea of the world around is simply is not quite all there is.

What I'm saying is, perhaps the speaker of the message is simply aware of the inevitable result of such, which, no matter how long it lasts (say X as freedom), it will inevitable turn into a certain state (say Y as lack of freedom).

Sure, he doesn't seem to offer much tangible evidence to that effect, but such is not required when it comes to hypothetical discussion or this flavor of philosophy.

In simple terms, say you're in a desert next to an oasis. The person is telling you that oasis, the water within, and as a result all life situated next to it that makes it unique from the barren desert-scape around it, is temporary. This is a fact. You consider what is temporary as a permanent concept, because, for all you know, and have ever known, it logically seems to be -- while the other person has seen that it is in fact, not. At least, that's a reasonable counter-argument to the aforementioned quote of yours. -

RussellA

2.7kIn effect, you are telling me to forget about having any freedom — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kIn effect, you are telling me to forget about having any freedom — Metaphysician Undercover

In a deterministic world, looking forwards in time, the earthquake off the coast of Cotabato in 1976 determined a tsunami in the Moro Gulf.

In a deterministic world, looking backwards in time, the reason for the tsunami in the Moro Gulf in 1976 was an earthquake off the coast of Cotabato.

You are at lunch and wonder whether you should have a glass of Merlot.

You reason it through. If you have a large glass then you will feel tired. If you feel tired then you may miss the train. If you miss the train then you may be stuck in the city. If you get stuck in the city then you will have to pay for a hotel. But you have no money on you. You therefore conclude that you will stick to a glass of water.

As with the Philippines example, the fact that you have a reason for having a glass of water does not mean that having a glass of water was not determined at the moment you wondered what you should drink.

The direction of reason is from the future to the past, even though the future is determined by the past. -

RussellA

2.7kAnd if we think of "physical matter" in this way, we get the appearance of an infinite regress, because each time we find what looks to be the fundamental elements, we then find out that they can be broken down into further spatial relations. — Metaphysician Undercover

RussellA

2.7kAnd if we think of "physical matter" in this way, we get the appearance of an infinite regress, because each time we find what looks to be the fundamental elements, we then find out that they can be broken down into further spatial relations. — Metaphysician Undercover

Not an infinite regress, as we eventually arrive at the (indivisible) fundamental particles and forces.

There are four fundamental interactions known to exist: Gravitational force, Electromagnetic force, Strong nuclear force, Weak nuclear force.

https://alevelphysics.co.uk/notes/particle-interactions/

===============================================================================

There is a strong argument for the ideality of spatial relations......................................The developing problem, is that as described above, the "spatial relations" are ideal, conceptual mathematics and geometry — Metaphysician Undercover

There is also a strong argument that ontological relations don't exist in the world but only the mind. As numbers and mathematics only exists in the mind (are invented not discovered), these relations are expressed in the mind mathematically.

FH Bradley made a regress argument against the ontological existence of relations in the world

From SEP - Relations:

===============================================================================Some philosophers are wary of admitting relations because they are difficult to locate. Glasgow is west of Edinburgh. This tells us something about the locations of these two cities. But where is the relation that holds between them in virtue of which Glasgow is west of Edinburgh?

This is why space itself needs to be understood as real active substance. — Metaphysician Undercover

Current scientific thinking seems to be that fundamental particles and forces exist in the world. Accepting that ontological relations between these fundamental particles and forces only exist in the mind, there is no necessity for space to be understood as a real active substance.

===============================================================================

Now we have a second possible intuition. Perhaps there is no fundamental matter at all, and the activity is simply the activity of space. What was represented as particles of matter existing in 'changing spatial relations', may actually be just 'changing spatial relations' without any real particles of matter. — Metaphysician Undercover

As I see it:

The fundamental particles and forces exist in the world as ontological Realism

The relations between these fundamental particles and forces exist in the mind as ontological idealism -

Apustimelogist

946Wittgenstein’s private language argument is a case in point, and recent philosophy has been much concerned about Dennett and others who seem to claim that our perceptions are all illusions. — Ludwig V

Apustimelogist

946Wittgenstein’s private language argument is a case in point, and recent philosophy has been much concerned about Dennett and others who seem to claim that our perceptions are all illusions. — Ludwig V

I don't think either of these philosophers claim that what you experience doesn't exist in some sense though. Dennett I believe is just refuting our conception of experience as representing something that transcends and is separate from, over and above, our biology. Wittgenstein is talking about how language is used, and I think it is more salient now than ever that his pointis correct given how LLMs are probably as good at talking about things like colour as we are. We can even learn things about colour from an LLM even though the LLM doesn't experience colours.

LLMs are demonstrating his beetle-in-box argument. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

Perhaps I should have explained properly. You are right, of course. Neither of them claims that what we experience doesn't exist. But the PLA is often treated as enormously paradoxical, as I'm sure you are aware. But Wittgenstein is only trying to demolish a philosophical myth, not deny that we can talk to ourselves. Again, Dennett is arguing that our perceptions are not what they seem to be, not that we don't have any.I don't think either of these philosophers claim that what you experience doesn't exist in some sense though. — Apustimelogist

Do you mean that they are capable of engaging in rational discourse without the benefit of human consciousness?LLMs are demonstrating his beetle-in-box argument. — Apustimelogist

Was he saying that relations don't really exist? Or just that they don't really exist in the physical world?FH Bradley made a regress argument against the ontological existence of relations in the world — RussellA

Quite so. I just wanted to suggest that even though Hegelian idealism was widely rejected, Berkeley was still remembered with approval in some positivist quarters.Only insofar as all were empiricists - 'all knowledge from experience'. IN other respects, chalk and cheese. Ayer and Carnap would have found Berkeley's talk of spirit otiose, to use one of their preferred words. — Wayfarer

I understand Berkeley as adopting a rather literal interpretation of substance and assigns it the role of "supporting (standing under) the existence of things". That was precisely what God was supposed to do - not only creating things, but maintaining them in existence. I'm sure you know about Malebranche and Occasionalism. Philosophers mostly seem to skate over Berkeley's project and its roots in the theology of the time. But, in a sense, it makes a nonsense of Berkeley's project to leave God out of it - not that he wasn't interested in science, as you point out.Note again that 'substance' here is from the Latin 'substantia', originating with the Greek 'ousia'. So it could equally be said 'there is not any other kind of being than spirit', which sounds to me less odd than 'substance' in the context. — Wayfarer

Oh, you certainly did make it clear. I'll take you word for it that he sees it as an abstracting. I rather think, though, that "bearer of predicates" is a translation into modern terminology. My point is only that, whatever exactly he is denying, he is clear that its conceptual role will be fill by the spiritual substance which is God.What Berkeley denies is the existence of corporeal substance, where 'substance' is used in the philosophical, rather than day-to-day, sense: the bearer of predicates, that which underlies appearances. He claims that is an abstraction - which is a point I hope I made sufficiently clear in the OP. — Wayfarer

That's trivially true. His problem is that once he has got people to grasp that he does believe that things do not exist unless they are perceived, they find wheeling in God to save himself from absurdity to be too little, too late.So he's saying objects of perception exist in perception - if not yours or mine, then the Divine Intellect, which holds them in existence. — Wayfarer

BTW I read somewhere - so it may not be true - that the second limerick was written by Berkeley himself. It was certainly published anonymously.

You were quite right to do so. I'm not sure what you are referring to. I wanted to stay near the heart of the matter, so had to be very selective, so it is not impossible that I failed to acknowledge what you actually said properly.Indeed, I did also mention that, to dispel the idea that Berkeley dismissed sensible objects as mere phantasms. — Wayfarer -

Apustimelogist

946Do you mean that they are capable of engaging in rational discourse without the benefit of human consciousness? — Ludwig V

Apustimelogist

946Do you mean that they are capable of engaging in rational discourse without the benefit of human consciousness? — Ludwig V

They are capable of intelligibly talking about experiences even though they don't even have the faculties for those experiences. An LLM has a faculty for talking, it doesn't have a faculty for seeing. The structure of language itself is sufficient for its intelligible use.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum