-

Wayfarer

26.2kLet's recall the point of the original post. It was that Bishop Berkeley's idealism was a reaction against the emerging scientific worldview which sought objectivity as the sole criterion of truth.

Wayfarer

26.2kLet's recall the point of the original post. It was that Bishop Berkeley's idealism was a reaction against the emerging scientific worldview which sought objectivity as the sole criterion of truth.

This was connected with the influence of the empirical philosophers, who said that all knowledge comes from (sensory) experience. It was also due to the decline of the 'participatory ontology' of scholastic philosophy, in which 'to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is.'

And finally, with Galileo and Locke's division of primary and secondary attributes, whereby the 'primary attributes' were the province of objective knowledge, and the secondary, how things appear or feel to us, relegated to the interior realm of subjectivity.

This is the origin of that distinctly modern form of consciousness, the Cartesian ego seeking to subordinate nature through science and technology. It permeates all of our awareness in today's world. -

J

2.5kWhat I don't think anyone can be at all certain about is as to what could be the metaphysical implications of such experiences. — Janus

J

2.5kWhat I don't think anyone can be at all certain about is as to what could be the metaphysical implications of such experiences. — Janus

Yes, my comments about certainty were meant to cover both the occurrence of the experience and the interpretation of it. So I'd call it highly likely, but by no means certain, that such experiences are "genuine" in that they do give access to a divine reality. Even using such a phrase, of course, takes us outside of philosophy entirely, in my opinion, though I know @Wayfarer thinks we can expand our understanding of what philosophy is and does so as to include it.

Note the qualifier, 'objective knowledge'. — Wayfarer

Right. I could say that a mystical experience is about something objective -- God or Divine Reality or whatever phrasing you like -- but only occurs subjectively. But the problem is how a subjective experience could provide evidence for sorting out the difference between some genuine objective reality and a mere psychological event, however powerful. In other words, my asserting the objective existence of what I'm experiencing doesn't make it so. How many such assertions would make it so? That's a complicated question, focusing on the blurred line between objectivity and intersubjectivity. A thousand mystics can all be wrong. Still, what we ideally want is an independent criterion that would tell us whether such a "genuine" experience is even possible. -

Constance

1.4kBut to understand why idealism is important, we need to be clear about what prompted its emergence in the early modern period, and what about it remains relevant. That is what I hope this brief essay has introduced. — Wayfarer

Constance

1.4kBut to understand why idealism is important, we need to be clear about what prompted its emergence in the early modern period, and what about it remains relevant. That is what I hope this brief essay has introduced. — Wayfarer

Simple, almost, to answer, but it does seem to be, as Heidegger said, the most remote from common sense, yet the most intimate in the midst of our being in the world. The reason why phenomenology persists is because it must, and it must because of the primordiality of phenomenality: It is impossible to observe anything but phenomena. And this deserves a dramatic, Period!

The reason why this is not understood is because it is embedded in some of the most difficult thinking there is; it goes beyond Kant into a labyrinth of neologistic language that most cannot or will not deal with. For me, to read Husserl throws the matter of our existence into a powerful indeterminacy that follows on the heels his neo Kantianism and leads to Heideggerian hermeneutics, and now all that is solid melts into air, philosophically. Hence the need for neologisms: for metaphysics was so burdened by centuries of bad thinking, and this thinking is embedded in language, and so the only way to remove this onto-theological core of metaphysics was to change the language of metaphysics, and bring ontology down from the heights of otherworldliness (Nietzsche partly inspired this, of course) into the finitude of actuality.

Anyway, what prompted its emergence is found in Kant, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, the Greeks, Hegel, etc., and what THIS is all about is, even prior to Husserl, the reduction-to-metaphysics discovered in an authentic analytic of what stands right before one's waking eyes. Note that this is just what Kant did to "discover" pure reason (those scare quotes are important): reduce ordinary experience to its logical structure, a structure that is there IN the foundational analysis of experience, and therefore not metaphysics at all---though we all know it really is THE most divisive metaphysics. One does not have to talk about noumena to see this: pure form Cannot be witnessed, only deduced. Deduced to what conclusion? Of course, the metaphysics of reason. Clearly, a big issue; one that divided philosophy in two. But while pure form cannot be witnessed and is hopelessly lost in mere groundless postulation (What is a ground regarding something that cannot be witnessed??), the world as it appears is no postulation at all. The appearance of appearing is as apodictically, well, appearing, as modus ponens. THIS is why phenomenology will not go away. It is certain, not merely likely, that when analytic philosophy learns to drop empirical science from its assumptions, anglo american thinking will turn to the phenomenon: the ONLY thing one has ever "observed" or can ever observe. -

Janus

18kYes, my comments about certainty were meant to cover both the occurrence of the experience and the interpretation of it. So I'd call it highly likely, but by no means certain, that such experiences are "genuine" in that they do give access to a divine reality. Even using such a phrase, of course, takes us outside of philosophy entirely, in my opinion, though I know Wayfarer thinks we can expand our understanding of what philosophy is and does so as to include it. — J

Janus

18kYes, my comments about certainty were meant to cover both the occurrence of the experience and the interpretation of it. So I'd call it highly likely, but by no means certain, that such experiences are "genuine" in that they do give access to a divine reality. Even using such a phrase, of course, takes us outside of philosophy entirely, in my opinion, though I know Wayfarer thinks we can expand our understanding of what philosophy is and does so as to include it. — J

Would you say that it is likely, if someone believes that certain kinds of altered states of consciousness give us access to a divine reality, that they were already inclined, most likely by cultural influences during their upbringing, to believe in a divine reality, and that others who do not have such an enculturated belief might interpret the experience as being a function of brain chemistry?

In other words, is not this world marvelous enough, if seen through fresh eyes? Wherefore the intuition of another world? Is it not more likely on account of a demand for perfection, and the surcease of all suffering and injustice and the introjection of cultural tropes that seem to promise those, than it is an unmediated intuition? -

J

2.5kWould you say that it is likely, if someone believes that certain kinds of altered states of consciousness give us access to a divine reality, that they were already inclined, most likely by cultural influences during their upbringing, to believe in a divine reality, and that others who do not have such an enculturated belief might interpret the experience as being a function of brain chemistry? — Janus

J

2.5kWould you say that it is likely, if someone believes that certain kinds of altered states of consciousness give us access to a divine reality, that they were already inclined, most likely by cultural influences during their upbringing, to believe in a divine reality, and that others who do not have such an enculturated belief might interpret the experience as being a function of brain chemistry? — Janus

Yes.

Wherefore the intuition of another world? — Janus

We know that such an intuition has been with humanity since there were civilizations, and no doubt before. Whether it's true or not, isn't really about one's predisposition to believe or disbelieve, wouldn't you agree?

Just to be clear, I don't think an argument from "common longstanding intuitions" can make the case. All it can do is provide evidence that the experiences under discussion have been given a mystical interpretation in many times and places -- along with plenty of non-mystical interpretations, I'm sure. Up until very recently most people had an intuition that the heavenly bodies revolved around the Earth. Well . . . nope. So anyone who doubts the validity of a longstanding intuition has every right to do so.

Again, this is why the topic is so recalcitrant to philosophical expression. I suppose we can do some work on the logic of "self-credentialing experiences," but that's not quite on the money. -

Janus

18kWe know that such an intuition has been with humanity since there were civilizations, and no doubt before. Whether it's true or not, isn't really about one's predisposition to believe or disbelieve, wouldn't you agree? — J

Janus

18kWe know that such an intuition has been with humanity since there were civilizations, and no doubt before. Whether it's true or not, isn't really about one's predisposition to believe or disbelieve, wouldn't you agree? — J

The problem is that the truth (or falsity) of such intuitions is not in any way definitively decidable. We can explain the universality of such intuitions in the moral context, as I said, as stemming from a demand that there should be perfection and justice. We can explain it in the epistemological context as being due to not having scientific explanations for phenomena. And we can explain it in the existential context as being on account of a universal fear of death. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI could say that a mystical experience is about something objective -- God or Divine Reality or whatever phrasing you like -- but only occurs subjectively. But the problem is how a subjective experience could provide evidence for sorting out the difference between some genuine objective reality and a mere psychological event, however powerful. In other words, my asserting the objective existence of what I'm experiencing doesn't make it so. How many such assertions would make it so? That's a complicated question, focusing on the blurred line between objectivity and intersubjectivity — J

Wayfarer

26.2kI could say that a mystical experience is about something objective -- God or Divine Reality or whatever phrasing you like -- but only occurs subjectively. But the problem is how a subjective experience could provide evidence for sorting out the difference between some genuine objective reality and a mere psychological event, however powerful. In other words, my asserting the objective existence of what I'm experiencing doesn't make it so. How many such assertions would make it so? That's a complicated question, focusing on the blurred line between objectivity and intersubjectivity — J

You may recall that this is the subject of my essay Scientific Objectivity and Philosophical Detachment. It is also a point made in this OP, that the word 'objectivity' only came into use in the early modern period. The background idea is that the pre-moderns had a very different sense of what is real. Their way-of-being in the world was participatory. The world was experienced as a living presence rather than a domain of impersonal objects and forces. In that context, the standard of truth was veritas - rather than objective validation. This state was realised through the emulation of the sacred archetypes rather than made the subject to propositional knowledge (per Hadot's Philosophy as Way of Life).

what prompted its emergence is found in Kant, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, the Greeks, Hegel, etc., and what THIS is all about is, even prior to Husserl, the reduction-to-metaphysics discovered in an authentic analytic of what stands right before one's waking eyes. — Constance

Thanks for your insightful comments! One of the books I've been studying the last couple of years is Thinking Being, Eric Perl. It helped me understand the sense in which metaphysics could be a living realisation, not the static religious dogma it has become. I've read parts of Heidegger's critique of metaphysics, but I'm not completely on board with his analysis. I think the flaw that he detects is that of 'objectification' - that philosophy errs in trying to arrive at an objective description of metaphysics, when its entire veracity rests on it being a state of lived realisation. (This is the subject of Perl's introductory chapter in the above book.)

You say this repeatedly, as if it were revealed truth, when in fact it’s simply the dogma of positivism: that only what can be scientifically validated can be stated definitively.The problem is that the truth (or falsity) of such intuitions is not in any way definitively decidable. — Janus

Religious orders have existed for millennia, during which countless aspirants have practiced and realized their principles. From the outside this may look like hearsay or anecdote, but that is because truths of this kind are first-person. They are not propositional or hypothetical, nor can they serve as scientific predictions.

As Karen Armstrong said

Religious truth is, therefore, a species of practical knowledge. Like swimming, we cannot learn it in the abstract; we have to plunge into the pool and acquire the knack by dedicated practice. Religious doctrines are a product of ritual and ethical observance, and make no sense unless they are accompanied by such spiritual exercises as yoga, prayer, liturgy and a consistently compassionate lifestyle. Skilled practice in these disciplines can lead to intimations of the transcendence we call God, Nirvana, Brahman or Dao. Without such dedicated practice, these concepts remain incoherent, incredible and even absurd.

The point isn’t that spiritual truths are “indecidable” in principle, but that they are not decidable by the methods of science. Their test is existential: whether practice transforms the one who undertakes it. -

Janus

18kYou say this repeatedly, as if it were revealed truth, when in fact it’s simply the dogma of positivism: that only what can be scientifically validated can be stated definitively. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kYou say this repeatedly, as if it were revealed truth, when in fact it’s simply the dogma of positivism: that only what can be scientifically validated can be stated definitively. — Wayfarer

Thanks for distorting what I've said yet again. I have never said that only what can be scientifically validated can be stated. It is obvious that we can state whatever we want to.

Instead I said that only in the case of statements whose assertions are either self-evident or demonstrable by observation can the truth or falsity be determined.

And Armstrong is wrong in my view...religious truth is not "a species of practical knowledge", it is religious practice which is a species of practical knowledge. There is no religious truth in any propositional sense.

Just as in science where the observed predictions of theories do not guarantee their truth, so it is with religious practice...that a practice may transform does not guarantee its truth. And further, the very notion of a true or false practice is inapt. Practices are efficacious or not, not true or false. -

Wayfarer

26.2kInstead I said that only in the case of statements whose assertions are either self-evident or demonstrable by observation can the truth or falsity be determined. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kInstead I said that only in the case of statements whose assertions are either self-evident or demonstrable by observation can the truth or falsity be determined. — Janus

Which is verificationism in a nutshell . I know you resent being described as positivist, but then you go ahead and make statements right out of the Ayer/Carnap playbook, so how else ought they to be described? The web definition of positivism is 'a philosophical system recognizing only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics and theism', which you frequently re-state.

There is no religious truth in any propositional sense. — Janus

The four ways of knowing: propositional knowing (knowing that facts are true), procedural knowing (knowing how to do something), perspectival knowing (knowing through a viewpoint), and participatory knowing (knowing through acting and being in an environment). -

Janus

18kWhich is verificationism in a nutshell . — Wayfarer

Janus

18kWhich is verificationism in a nutshell . — Wayfarer

No, it's not: verificationism is a theory in the philosophy of science. I've already said that scientific theories cannot be verified to be true, so I don't agree with verificationsim. I don't reject metaphysics; in fact I agree with Popper that, even thought the truth of metaphysical theses cannot be determined by either verification or falsification, they can provide a stimulus that may lead to important scientific results.

Popper himself acknowledges that scientific theories can only be definitively falsified, not verified. I don't believe they can even be definitively falsified. We believe they are true or not only on the grounds of predictive success and general plausibility. As to my attitude to metaphysics: metaphysical speculation is fun, and some of the idea can be inspiring for creative pursuits.

I keep asking you to explain how the truth of any metaphysical thesis could be determined, and you never even attempt to answer the question, which is telling; it seems to show that you are in a kind of denial...not wanting to abandon precious beliefs. It would help the discussion if you read more carefully, and curbed your tendency to jump to silly conclusions about what's being said.

We can verify simple everyday observations such as that plants usually grow better if you feed them with the appropriate fertilizer. There are millions of examples of such easily verified truths.

Yes I was already familiar with those conceivable modes of knowing, I formulated them myself before I ever came across them in Vervaeke's lectures.The four ways of knowing: — Wayfarer

Truth and falsity, in the sense I intended in this discussion are properties of sentences, or assertions, or propositions. How would you determine the truth of "consciousness is fundamental to reality"? I am not even sure what it means, let alone how I could find out if it true or not. I think you need to open your mind a little. -

Wayfarer

26.2kverificationism is a theory in the philosophy of science — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kverificationism is a theory in the philosophy of science — Janus

It is not! Verificationism is not specific to philosophy of science. It is a central tenet of positivism and was associated with the Vienna Circle and A J Ayer (reference).

So this statement:

I said that only in the case of statements whose assertions are either self-evident or demonstrable by observation can the truth or falsity be determined. — Janus

is verificationism, plain and simple. And if you add

even though the truth of metaphysical theses cannot be determined by either verification or falsification, they can provide a stimulus that may lead to important scientific results. — Janus

Then you're still saying the only criterion of factuality is science, again.

I keep asking you to explain how the truth of any metaphysical thesis could be determined, and you never even attempt to answer the question, which is telling; it seems to show that you are in a kind of denial — Janus

I spend lot of time addressing your objections. I write, publish and defend opinion pieces here and on Medium and will always attempt to address questions and criticisms. I have about the second most number of posts on this forum and a very large proportion of them are responses to criticisms.

What I observe of your modus operandi is that there are many questions in philosophy about which you will say there are no determinable facts. Then you'll say, because they're incapable of being determined, therefore nobody can answer them, therefore empiricism is the most plausible attitude.

How to test a 'metaphysical theory'? Just now Kastrup was interviewed by Robert Lawrence Kuhn, he suggests internal consistency, explanatory power, and parsimony would be good starting points. I would concur with that.

But as Karen Armstrong says, spiritual truth is a species of practical knowledge. Like swimming, we can't learn it in the abstract; we have take the plunge. We have to make it meaningful by engaging with it. And that can only be done first person.

How would you determine the truth of "consciousness is fundamental to reality"? I am not even sure what it means — Janus

Plainly! -

J

2.5kWe can explain the universality of such intuitions in the moral context, as I said, as stemming from a demand that there should be perfection and justice. We can explain it in the epistemological context as being due to not having scientific explanations for phenomena. And we can explain it in the existential context as being on account of a universal fear of death. — Janus

J

2.5kWe can explain the universality of such intuitions in the moral context, as I said, as stemming from a demand that there should be perfection and justice. We can explain it in the epistemological context as being due to not having scientific explanations for phenomena. And we can explain it in the existential context as being on account of a universal fear of death. — Janus

All true, if you mean "offer as possible explanations." But another way we can explain it is in the accuracy or correspondence-to-the-facts context -- that is, these intuitions are correct as to their source.

But . . . how do we determine which context, which putative explanation, is the right one? This is what you and @Wayfarer are thrashing out.

You may recall that this is the subject of my essay Scientific Objectivity and Philosophical Detachment. — Wayfarer

Yes, good piece of work.

the pre-moderns had a very different sense of what is real. — Wayfarer

Indeed. So we have the question, Is there anything to guide us in choosing between these different senses? The question lends itself to special pleading, as I'm sure you're aware: It's tempting, and convenient, to say, "Oh, when it comes to what is scientifically real, the pre-moderns were hopelessly wrong, but with spiritual reality the reverse is true; it's we who don't understand."

The world was experienced as a living presence rather than a domain of impersonal objects and forces. In that context, the standard of truth was veritas - rather than objective validation. — Wayfarer

Not sure this was across the board, but let's say it was. We're still left with asking, "OK, how well did they do, truth-wise?" Is there a meta-level from which such a question can be addressed? For me, this pushes us to the boundary of what philosophy can talk about.

they are not decidable by the methods of science. Their test is existential: whether practice transforms the one who undertakes it. — Wayfarer

And this illustrates why. Personal transformation is inaccessible to science, but nothing could be more important to the person himself or herself. The results of spiritual practice (including in my own life) form part of my reason for saying that the mystical revelation is "very likely" true. But I'm still not prepared to call my belief knowledge. Trying to be honest, I'm aware that I could be wrong, there could be other explanations. All I can do is assert that these other explanations look much less plausible to me than the traditional, spiritual explanations. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIndeed. So we have the question, Is there anything to guide us in choosing between these different senses? The question lends itself to special pleading, as I'm sure you're aware: It's tempting, and convenient, to say, "Oh, when it comes to what is scientifically real, the pre-moderns were hopelessly wrong, but with spiritual reality the reverse is true; it's we who don't understand." — J

Wayfarer

26.2kIndeed. So we have the question, Is there anything to guide us in choosing between these different senses? The question lends itself to special pleading, as I'm sure you're aware: It's tempting, and convenient, to say, "Oh, when it comes to what is scientifically real, the pre-moderns were hopelessly wrong, but with spiritual reality the reverse is true; it's we who don't understand." — J

There was plenty wrong about the pre-modern world, no question. But there's a definite historical trajectory. In the forum environment it's impossible to go into all of the details. For instance, I only discovered John Vervaeke's lectures in 2022, but his original 'Awakening from the Meaning Crisis' series comprises 52 hours of material! And that there really is such a crisis, I have no doubt, although it's never hard for the naysayers to say 'prove it' and then shoot at anything that's offered by way of argument. I understand that the kind of argument I'm presenting is an attempt to describe an aspect of this historical trajectory as it developed over centuries, but I'm trying to retrace the steps, so to speak.

As for 'pushing the boundaries of what philosophy can talk about', I do agree. But consider this passage from Thomas Nagel:

Plato was clearly concerned not only with the state of his soul, but also with his relation to the universe at the deepest level. Plato’s metaphysics was not intended to produce merely a detached understanding of reality. His motivation in philosophy was in part to achieve a kind of understanding that would connect him (and therefore every human being) to the whole of reality – intelligibly and if possible satisfyingly. — Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament

One of the aspects of the 'meaning crisis' is this sharp but often tacit division between religion and science. This manifests frequently as criticism of idealist arguments on the grounds that they're basically appeals to religious faith. But many of these criticisms are in turn grounded on a stereotyped model of religion, which in turn is based on the very history that produced 'the meaning crisis' in the first place. -

J

2.5kA thoughtful response. I have no opinion about the meaning crisis; my earlier comment was meant to point out that standards of truth, as they may vary from era to era, are themselves subject to critique from a viewpoint. So whether there's a way of evaluating a mystical experience that can call upon concepts of non-objective truth, or the kind of truth you describe as valid and important to the pre-moderns, is itself a matter that may be either true or false -- but according to which lights? "Veritas" vs. "objective validation" -- we appear to need a commitment to one or the other of these standards before being able to say which is more reliable, or more appropriate for a given question. Thus, the snake eventually swallows its own tail.

J

2.5kA thoughtful response. I have no opinion about the meaning crisis; my earlier comment was meant to point out that standards of truth, as they may vary from era to era, are themselves subject to critique from a viewpoint. So whether there's a way of evaluating a mystical experience that can call upon concepts of non-objective truth, or the kind of truth you describe as valid and important to the pre-moderns, is itself a matter that may be either true or false -- but according to which lights? "Veritas" vs. "objective validation" -- we appear to need a commitment to one or the other of these standards before being able to say which is more reliable, or more appropriate for a given question. Thus, the snake eventually swallows its own tail.

But this is an issue that pervades every philosophical discourse, not only talk of subjective experience.

Nagel, and you, are right about Plato and about how philosophy was conceived for many centuries. So if someone wanted to say, "Heck, if Plato wasn't a philosopher, than who is?" I couldn't object. Yet there is a different sense of philosophy as a developing discipline -- or if that's too biased, at least an evolving, changing one. I do think we've made progress, in the last 100 years or so, in understanding what can be meaningfully discussed within philosophy. It's a good thing that we've been able to set limits on our attempts to wrestle experience into the rational language of analytic philosophy. On my view, this still leaves plenty for language, and life, to do. (Not to mention Continental phil!) -

Janus

18kIt is not! Verificationism is not specific to philosophy of science. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kIt is not! Verificationism is not specific to philosophy of science. — Wayfarer

That's strictly true―I misspoke. What I had in mind was that it is a thesis in epistemology., and it is commonly, as applied to scientific theories, compared to and contrasted with Popper's falsificationism. the Wiki entry says:

Verificationism, also known as the verification principle or the verifiability criterion of meaning, is a doctrine in philosophy which asserts that a statement is meaningful only if it is either empirically verifiable (can be confirmed through the senses) or a tautology (true by virtue of its own meaning or its own logical form). Verificationism rejects statements of metaphysics, theology, ethics and aesthetics as meaningless in conveying truth value or factual content, though they may be meaningful in influencing emotions or behavior.[1]

Scientific statements (in the broadest sense as statements of what is observed) are along with tautologous statements are taken to be the only kinds of statements which can be definitively verified.

I am not a positivist in that I don't believe non-verifiable statements are meaningless. Apart from the observational aspect, the other aspect of science―the theoretical is not itself strictly verifiable.

Then you're still saying the only criterion of factuality is science, again. — Wayfarer

No, I'm saying the criterion of factuality is observability. How can be sure that a statement is factual if what it asserts is not observable? Following that reasoning a statement is factuality-apt, i.e. could be either a fact or not, if what is proposes is, at least in principle, checkable by observation.

You keep summoning the positivist bogey man, but this is an evasive tactic designed to discredit your interlocutor. I've asked you to cite one fact or piece of knowledge that is not based in observations of or about this world; that is not, in other words, based in human cognition of the world. Apparently you are both incapable of that, and incapable of admitting that you are incapable of that.

How to test a 'metaphysical theory'? Just now Kastrup was interviewed by Robert Lawrence Kuhn, he suggests internal consistency, explanatory power, and parsimony would be good starting points. I would concur with that. — Wayfarer

Not "how to test", but "how to evaluate".

All true, if you mean "offer as possible explanations." But another way we can explain it is in the accuracy or correspondence-to-the-facts context -- that is, these intuitions are correct as to their source.

But . . . how do we determine which context, which putative explanation, is the right one? This is what you and Wayfarer are thrashing out. — J

Can you explain what you mean by "these intuitions are correct as to their source"? I'm trying to thrash out how we should categorize what is knowledge and what faith. Wayfarer is more just thrashing about, reacting emotionally to what he apparently sees as personal attacks, as attacks on his beliefs. I'm not attacking the beliefs, but the presumption that those beliefs are demonstrably true. -

Wayfarer

26.2kYet there is a different sense of philosophy as a developing discipline -- or if that's too biased, at least an evolving, changing one. I do think we've made progress, in the last 100 years or so, in understanding what can be meaningfully discussed within philosophy. It's a good thing that we've been able to set limits on our attempts to wrestle experience into the rational language of analytic philosophy — J

Wayfarer

26.2kYet there is a different sense of philosophy as a developing discipline -- or if that's too biased, at least an evolving, changing one. I do think we've made progress, in the last 100 years or so, in understanding what can be meaningfully discussed within philosophy. It's a good thing that we've been able to set limits on our attempts to wrestle experience into the rational language of analytic philosophy — J

Sure, I'd agree with that. I'm constantly on the lookout for new ideas, and the general tenor of academic philosophy changes constantly. There's a huge sea-change going on, with 'consciousness studies' and Robert Lawrence Kuhn's 'Closer to Truth' and John Vervaeke's endeavours (plus the infinite backlog of things I haven't read yet.)

But I'll try and re-state the aim of the OP. It was prompted by an assertion that Scholastic philosophy was 'realist' and would have been critical of what we now call 'idealism' (although I can't even recall where I read that now!) But I felt it was an anachronistic criticism, because Scholastic philosophy was not at all 'realist' in the sense we now understand the word. They were realist with respect to universals, whereas nowadays, realism concerning universals is categorised as Aristotelian or Platonic and basically relegated to the margins of debate. Realism nowadays usually means objective realism. I am trying to argue that idealism, both in Berkeley and Kant, was a reaction against the emerging nominalist-empiricist framework that now dominates philosophy and culture. -

J

2.5kCan you explain what you mean by "these intuitions are correct as to their source"? — Janus

J

2.5kCan you explain what you mean by "these intuitions are correct as to their source"? — Janus

Yes, it wasn't very well put. I only meant that, in addition to the possible explanations you named, it's also possible that the universality of mystical intuitions is explained by their actually being what they claim to be, namely experiences of God or some transcendent consciousness.

. . . the presumption that those beliefs are demonstrably true. — Janus

I haven't followed every post between you and @Wayfarer today, so I'll just speak for myself. I don't think a statement like "I have had an experience of the Godhead" or "My third eye opened" or "I encountered Jesus and was born again" or any of the countless variants of this should be presumed to be "demonstrably true." Nor are they demonstrably false. It's not clear to me that they can be separated from 3rd-person/objective claims such as "God exists".

All I can say is, we're left with possible explanations, possible ways of assigning probability values to the statements under discussion. And we'll rate these probabilities differently, based on our own knowledge and experience -- just as we would for any topic that's tough to know about for sure. I see plenty of daylight between "My account of my mystical experience is demonstrably true" and "Here's what I think probably accounts for my experience." The latter seems unexceptionable to me. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kFor instance, I only discovered John Vervaeke's lectures in 2022, but his original 'Awakening from the Meaning Crisis' series comprises 52 hours of material! And that there really is such a crisis, I have no doubt, although it's never hard for the naysayers to say 'prove it' and then shoot at anything that's offered by way of argument. — Wayfarer

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kFor instance, I only discovered John Vervaeke's lectures in 2022, but his original 'Awakening from the Meaning Crisis' series comprises 52 hours of material! And that there really is such a crisis, I have no doubt, although it's never hard for the naysayers to say 'prove it' and then shoot at anything that's offered by way of argument. — Wayfarer

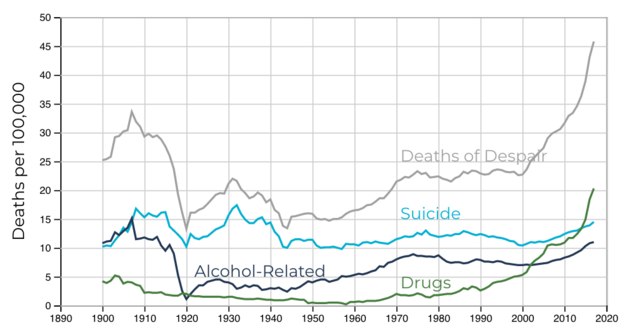

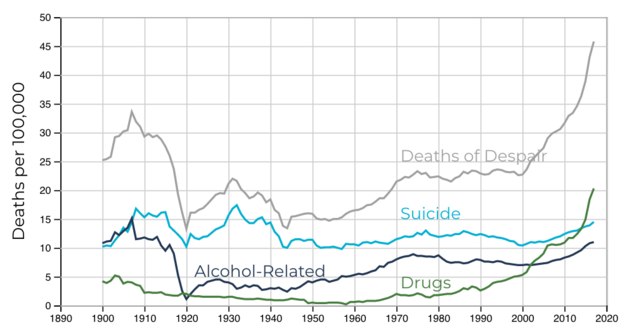

I've thought about this sort of thing for a bit, and I'm trying to put my finger on some patterns. For instance, there is a sort of "perennial problem" fallacy. It works like this: if a problem is always around—e.g., "people have always committed suicide and become addicts"—this is used as somehow precluding the idea that this problem could become particularly acute in a given epoch or place. But the driving causes of Russia's abysmal male life expectancy after the fall of the USSR show that this sort of thing can vary wildly, having the same level of effect as major wars. Or less dramatically:

I came across a different explanation recently as well. In the Problem of Pain, C.S. Lewis takes up the modern reduction of all virtues to kindness and the claim that our era is kinder than past eras. Perhaps it is so, although he does ask if kindness is really a virtue if it doesn't cost one anything. I think there is a valid point there in that we might be said to be coasting on past successes.

But either way, his more salient point was that, even if our own era excels in one particular virtue, it doesn't mean it excels in every virtue. For instance, even if we are kinder, this does not mean that we possess greater fortitude, greater prudence, greater courage, greater chastity, greater hope, greater temperance, etc. Even if our era was "the best" that still wouldn't mean that there would be nothing worthy of emulation in prior epochs. For, even if we are the most scientific and kind, it would still be the case that if we were also the most temperate and had the greatest fortitude things could be much better. I'd even say that it's possible that an increase in intellectual virtue and techne has helped paper over declines in other areas, or to set the stage for vice (just consider the cornucopia of addictive drugs unlocked by our innovations).

I think here about the Amish who, for all their faults (and they are many and severe) manage to outlive and build up greater wealth than their neighbors (despite huge household sizes to split inheritances), all whilst eschewing centuries of technological progress, largely due to an ability to foster a few key virtues.

Then there is the issue of framing. This article from the Guardian, which is a great reminder that propaganda takedowns are sometimes subtle (consider who they felt the need to focus on first and the title they chose) is a great example. It focuses on homesteading and a sort of ascetic way of life and explains it by saying:

The “paradox of choice” is the theory that humans, when offered too many options, become overwhelmed and unhappy. If liberal consumer capitalism is underpinned by the belief that individual autonomy and choice should be society’s highest values, then perhaps the trad movement is one response to the decision paralysis of modern liberal life.

Faced with a dizzying barrage of technological, social and consumer choices, some people prefer fewer options: duties rather than rights, constraints rather than freedoms, defined roles rather than elastic identities.

That narrowing is part of a larger reaction against modernity, a frustrated feeling that our secular technological age promised progress and instead brought loneliness, worsening material prospects and a numbing onslaught of social media, spam, porn, gambling, gaming and AI slop, with the cold hand of capitalism – or Satan, or both – extending further into our lives with every chime, buzz and click.

That is, the problem is almost that things are "too good" or at least "too free." But I wish a self-described expert in this area would at least offer up the way this sort of movement is justified in its own, and not only liberal terms. The internal interpretation there would not be that we have "too much freedom," but—in line with Plato, Epicetus, Rumi, etc.—that freedom requires virtue, and that these efforts help to foster virtue. It is rather consumerist neoliberalism that educates us in vice, and so deprives us of liberty. That is, you don't automatically become self-determining and self-governing by turning 18 and avoiding severe misfortune. It is rather, considerable work, and involves a sort of habit formation and training.

I wouldn't call this a fallacy so much as an inability to step outside a particular frame (in particular, a specifically modern notion of liberty). So, a group that is acting precisely to achieve greater self-determination and liberty is instead described as fleeing liberty for comfort (which is, ironically, how the decadence of modernity is often described as well). My point would be that both critiques have a good deal of teeth, but the critique of liberalism will probably tend to hit harder because its dominance makes it harder to escape (whereas fringe movements are contained within a volanturist system where membership is "at will.") -

Wayfarer

26.2kIt is rather consumerist neoliberalism that educates us in vice, and so deprives us of liberty. That is, you don't automatically become self-determining and self-governing by turning 18 and avoiding severe misfortune. It is rather, considerable work, and involves a sort of habit formation and training — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.2kIt is rather consumerist neoliberalism that educates us in vice, and so deprives us of liberty. That is, you don't automatically become self-determining and self-governing by turning 18 and avoiding severe misfortune. It is rather, considerable work, and involves a sort of habit formation and training — Count Timothy von Icarus

Totally. And I'm not holding myself up as an exemplar of one who has managed to accomplish that - in fact I'm rather driven by the gloomy awareness of the extent to which I am susceptible to being corrupted by the culture I've been born into. The 'inability to step outside the frame' is what I mean by learning to look at your spectacles and not just through them.

Incidentally as I introduced Vervaeke to the conversation, I will do him the courtesy of providing his statement of the problem in the introduction to the series:

We are in the midst of a mental health crisis. There are increases in anxiety disorders, depression, despair, suicide rates are going up in North America, parts of Europe, other parts of the world. And that mental health crisis is itself due to and engaged with crises in the environment and the political system. And those in turn are immeshed within a deeper cultural historical crisis. I called the meaning crisis. So the meaning crisis expresses itself and many people are giving voice to this in many different ways, is this increasing sense of bullshit. Bullshit is on the increase. It's more and more pervasive throughout our lives and there's this sense of drowning in this old ocean of bullshit. And we have to understand why is this the case and what can we do about it? So today there is an increase of people feeling very disconnected from themselves, from each other, from the world, from a viable and foreseeable future.

Let's discuss this. Let's work on it together. Let's rationally reflect on it. What can we do about the meaning crisis? These problems are deep problems that we're facing. Many people are talking about the meaning crisis, but what I want to argue is that these problems are deeper than just social media problems, political problems, even economic problems. They're deeply historical, cultural, cognitive problems, and we need to, we need to penetrate into them carefully and rigorously. Getting out of this problem is going to be tremendously difficult. It's going to require significant transformations in our cognition, our culture, our communities, and in order to move forward in such a difficult manner, we have to reach more deeply into our past to salvage the resources we can for such an amazing challenge.

I'll be talking about a lot of people who have spoken in in ways that will provide us the resources we need. We'll talk about ancient figures like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, Jesus of Nazareth, Siddhartha, Gautama, the Buddha, but we'll also talk about modern pivotal figures. We'll talk about people like Carl Jung. We'll talk about Nietzsche. We'll talk about Heidegger. We'll talk about current work being done by psychologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists. We're going to cover a broad range of topics. We're going to talk about shamanism and altered States of consciousness related a modern things like psychedelic experience, mystical experience. But we'll also talk about existentialism, nihilism. We'll talk about AI, artificial intelligence. What's that telling us? But also what can our evolutionary past tell us about how we wrestle with the meaning crisis. So this is a complex and difficult problem. There are no easy answers. We need to go through this very carefully and rigorously. We got to get clear about what the problem is and clear about what our answer could be. So I want to bring all of this together in a coherent and clear fashion so that we together can discover how to awaken from the meaning crisis. — Awakening from the Meaning Crisis (YouTube) -

J

2.5kScholastic philosophy was not at all 'realist' in the sense we now understand the word. They were realist with respect to universals, — Wayfarer

J

2.5kScholastic philosophy was not at all 'realist' in the sense we now understand the word. They were realist with respect to universals, — Wayfarer

Is this right? I don't know Scholastic philosophy very deeply, but I thought that the concept of intelligibility meant that we can know what is real in the physical world as well. -

Constance

1.4kThanks for your insightful comments! One of the books I've been studying the last couple of years is Thinking Being, Eric Perl. It helped me understand the sense in which metaphysics could be a living realisation, not the static religious dogma it has become. I've read parts of Heidegger's critique of metaphysics, but I'm not completely on board with his analysis. I think the flaw that he detects is that of 'objectification' - that philosophy errs in trying to arrive at an objective description of metaphysics, when its entire veracity rests on it being a state of lived realisation. (This is the subject of Perl's introductory chapter in the above book.) — Wayfarer

Constance

1.4kThanks for your insightful comments! One of the books I've been studying the last couple of years is Thinking Being, Eric Perl. It helped me understand the sense in which metaphysics could be a living realisation, not the static religious dogma it has become. I've read parts of Heidegger's critique of metaphysics, but I'm not completely on board with his analysis. I think the flaw that he detects is that of 'objectification' - that philosophy errs in trying to arrive at an objective description of metaphysics, when its entire veracity rests on it being a state of lived realisation. (This is the subject of Perl's introductory chapter in the above book.) — Wayfarer

The lived realization you talk about refers to Husserl's epoche. There are phenomenologists who take this reduction all the way down, apophatically, if you will, to an ontological revelation. I have always thought the quintessential phenomenologist to be the Buddhist, keeping in mind though that even the competent and committed meditator has to pass through, that is, undo and outright violate, the interpretative structures of understanding that have taken a lifetime to build, and while one may stand on an extraordinary threshold, the decisive move forward has to deal with these structures that always already make affirmation: the tree is still a tree, the clock a clock---the doldrums of ordinary experience that are the very temporal foundations of our being. This is Heidegger's dasein, Kierkegaard's hereditary "sin", the totality that is me-in-the-world. Heidegger takes one to water, so to speak, but does affirm the validity of drinking. To really do this, I am convinced one has to leave standard relations with the world behind, a monumental task. Psychologists will call this disassociation, a pathology. Radical insight is a radical existence in which it is the psychologist is now seen as dissociated, alienated. I don't read the Christian Bible much--read it once in a course called The Bible as Literature--but I do recall Jesus saying one must hate pretty much everyone to be a true devotee. Now, 'hate' is a problematic translation from the Aramaic, but even a tame reading tells us to set aside everyone (and everything), put them out of mind, dismiss them from thought and feeling. (Incidentally, I do read now and again, Tolstoy's Gospels in Brief, which Wittgenstein use to carry around wherever he went. Tolstoy was no fool.)

Anyway, it is like two very different worlds that are radically opposed, yet a unity, what Michel Henry calls ontological monism: in the being of beings, beings fall away, meaning one no longer sees a tree there, a fence post beside the tree, the sky above, and so on, for all of these categories of thought yield to what is "stable and absolute" and this can only be acknowledged in the phenomenological reduction: not simply a concept, but a consummatory experience.

Thanks for Eric Perl. I will give him a read. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI don't know Scholastic philosophy very deeply, but I thought that the concept of intelligibility meant that we can know what is real in the physical world as well. — J

Wayfarer

26.2kI don't know Scholastic philosophy very deeply, but I thought that the concept of intelligibility meant that we can know what is real in the physical world as well. — J

Nor do I, but the theme I'm exploring is more like a current in the history of ideas, which shows up in Scholastic philosophy. But what was 'real' to the scholastics, was not the physical world as such. When we say “physical world,” we usually mean what modern physics investigates—matter, energy, and their interactions. But for St. Thomas, there was no such concept as a self-subsisting “physical” realm. The world was composed of created beings, each a union of form and matter, whose being itself is dependent on God as ipsum esse subsistens (being itself). In that sense, he would not have recognized “the physical world” in the sense we do today.

Summa Theologiae I, q. 85, a. 1 (On whether our intellect can know material things)

“The intellect does not know matter except as it is under form.”

(intellectus non cognoscit materiam nisi secundum quod est sub forma)

Sensible Form and Intelligible Form:

Reveal“EVERYTHING in the cosmic universe is composed of matter and form. Everything is concrete and individual. Hence the forms of cosmic entities must also be concrete and individual. Now, the process of knowledge is immediately concerned with the separation of form from matter, since a thing is known precisely because its form is received in the knower. But, whatever is received is in the recipient according to the mode of being that the recipient possesses. If, then, the senses are material powers, they receive the forms of objects in a material manner; and if the intellect is an immaterial power, it receives the forms of objects in an immaterial manner. This means that in the case of sense knowledge, the form is still encompassed with the concrete characters which make it particular; and that, in the case of intellectual knowledge, the form is disengaged from all such characters. To understand is to free form completely from matter.

“Moreover, if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized. Intellectual knowledge is analogous to sense knowledge inasmuch as it demands the reception of the form of the thing which is known. But it differs from sense knowledge so far forth as it consists in the apprehension of things, not in their individuality, but in their universality.

“The separation of form from matter requires two stages if the idea is to be elaborated: first, the sensitive stage, wherein the external and internal senses operate upon the material object, accepting its form without matter, but not without the appendages of matter; second the intellectual stage, wherein agent intellect operates upon the phantasmal datum, divesting the form of every character that marks and indentifies it as a particular something.

“Abstraction, which is the proper task of active intellect, is essentially a liberating function in which the essence of the sensible object, potentially understandable as it lies beneath its accidents, is liberated from the elements that individualize it and is thus made actually understandable. The product of abstraction is a species of an intelligible order. Now possible intellect is supplied with an adequate stimulus to which it responds by producing a concept. — Sensible Form and Intelligible Form - From Thomistic Psychology, by Robert E. Brennan, O.P., Macmillan Co., 1941

The Cultural Impact of Empiricism

RevealFor Empiricism there is no essential difference between the intellect and the senses. The fact which obliges a correct theory of knowledge to recognize this essential difference is simply disregarded. What fact? The fact that the human intellect grasps, first in a most indeterminate manner, then more and more distinctly, certain sets of intelligible features -- that is, natures, say, the human nature -- which exist in the real as identical with individuals, with Peter or John for instance, but which are universal in the mind and presented to it as universal objects, positively one (within the mind) and common to an infinity of singular things (in the real).

Thanks to the association of particular images and recollections, a dog reacts in a similar manner to the similar particular impressions his eyes or his nose receive from this thing we call a piece of sugar or this thing we call an intruder; he does not know what is sugar or what is intruder. He plays, he lives in his affective and motor functions, or rather he is put into motion by the similarities which exist between things of the same kind; he does not see the similarity, the common features as such. What is lacking is the flash of intelligibility; he has no ear for the intelligible meaning. He has not the idea or the concept of the thing he knows, that is, from which he receives sensory impressions; his knowledge remains immersed in the subjectivity of his own feelings -- only in man, with the universal idea, does knowledge achieve objectivity. And his field of knowledge is strictly limited: only the universal idea sets free -- in man -- the potential infinity of knowledge.

Such are the basic facts which Empiricism ignores, and in the disregard of which it undertakes to philosophize. — The Cultural Impact of Empiricism, Jacques Maritain

How this relates to 'Idealism in Context'

The thesis is that the medievals operated within a participatory ontology — a “knowing by being,” where intelligibility arises through the interplay of form and matter, and ultimately through participation in God’s act of being. In this framework, “matter alone” was unintelligible; as Aquinas put it, “prime matter cannot be known in itself, but only through form” (per Eric Perl).

This was increasingly challenged by the emerging paradigm of modernity, which sought to secure knowledge through objectivity — facts conceived as mind-independent, accessible to a detached observer. The sense of separateness entailed by this paradigm was alien to the scholastic worldview.

Idealism arises in early modern philosophy as a reaction against this development. There are of course caveats: Berkeley converges with Aquinas in rejecting the idea of an unknowable material substrate, yet diverges in rejecting universals. Kant, meanwhile, re-interprets hylomorphism in transcendental terms, shifting form and matter into the structures of cognition. But in their different ways, both Berkeley and Kant resisted the notion of a self-subsistent physical domain, independent of mind altogether.

---------------

The lived realization you talk about refers to Husserl's epoche. — Constance

Quite. There is also a geneological relation between Buddhism and Pyrrhonic scepticism, purportedly owing to Pyrrho of Elis travelling to Gandhara (today's Kandahar in Afghanistan, but then a Buddhist cultural centre) and sitting with the Buddhist philosophers. See Epochē and Śūnyatā.

To really do this, I am convinced one has to leave standard relations with the world behind, a monumental task. — Constance

Renunciation, in a word.

The tree is still a tree, the clock a clock — Constance

'First, there is a mountain; then there is no mountain; then there is' ~ Dogen Zen-ji

'If one takes the everyday representation as the sole standard of all things, then philosophy is always something deranged' ~ Martin Heidegger, 'What is a Thing?' -

JuanZu

382With the benefit of hindsight, at least some of Berkeley’s philosophy remains plausible. In On Physics and Philosophy (2006), physicist Bernard d’Espagnat refers to Bishop Berkeley — not to endorse his immaterialism, but to acknowledge that quantum theory has unsettled the once-unquestioned assumption of an observer-independent reality⁸. Paradoxically, a scientific revolution formerly anticipated as the pinnacle of physical realism ends up reviving precisely the kind of metaphysical questions Berkeley posed in the early 18th century! — Wayfarer

JuanZu

382With the benefit of hindsight, at least some of Berkeley’s philosophy remains plausible. In On Physics and Philosophy (2006), physicist Bernard d’Espagnat refers to Bishop Berkeley — not to endorse his immaterialism, but to acknowledge that quantum theory has unsettled the once-unquestioned assumption of an observer-independent reality⁸. Paradoxically, a scientific revolution formerly anticipated as the pinnacle of physical realism ends up reviving precisely the kind of metaphysical questions Berkeley posed in the early 18th century! — Wayfarer

I have always been somewhat perplexed by this. The Copenhagen interpretation revives a strong idealism like that of Berkeley. My position, as seen elsewhere, attempts to rid quantum physics of this idealism, which implies rejecting the Copenhagen interpretation. There is a mentalism, or mental causation, which, in my opinion, must be eliminated from the interpretation of quantum physics. But such elimination requires naturalising the measuring apparatus. In other words, understanding that it is our measuring apparatus that interacts with this quantum reality and not our subjectivity. Our subjectivity cannot interact with, say, the box in which the cat is placed. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI take your point that we should not confuse subjectivity with the role of the measuring apparatus. Of course it is the detector, not personal awareness, that interacts with the system. But the question that persists — and this is what makes the problem metaphysical — is: why does the interaction only count as a measurement when it enters the domain of observables, that is, when it becomes information available to us?

Wayfarer

26.2kI take your point that we should not confuse subjectivity with the role of the measuring apparatus. Of course it is the detector, not personal awareness, that interacts with the system. But the question that persists — and this is what makes the problem metaphysical — is: why does the interaction only count as a measurement when it enters the domain of observables, that is, when it becomes information available to us?

In other words, the physics itself says that quantum systems evolve continuously according to the Schrödinger equation until a “measurement” occurs. We can naturalise the apparatus, but we have still not eliminated the conceptual distinction between interaction in general and the interaction that produces definite outcomes. This is why Copenhagen does not simply dissolve into realism: the transition from indeterminate states to determinate observations remains stubbornly tied to the framework of knowledge, including the observer - not just to physical process. That is the sense in which it transgresses objectivity.

That’s what I was getting at by mentioning Berkeley and d’Espagnat. Not that the ‘mind causes reality’ in a gross sense, but that the very structure of quantum theory reopens the question of how far reality can be described apart from the conditions of observation. That’s why Berkeley often crops up in these conversations: he represents one pole in the dialectic, so to speak. After all there’s plainly a resonance between Bohr’s ‘no phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is observed’ and ‘esse est percipe’. It is what caused Einstein to ask ‘does the moon not continue to exist when nobody is looking?’.

Mind you Bohr himself strenuously resisted any idea of subjectivity in the obvious sense. He didn’t say that consciousness collapses the wavefunction (that was Wigner, later, but even he then later abandoned the idea); Rather, Bohr insisted that what counts as a “phenomenon” in quantum mechanics is the indivisible whole of the system-plus-the-measuring-apparatus. The observer enters only insofar as we need a shared, classical description to record and communicate the outcome. But this is precisely what raises the philosophical tension: even while Bohr denied the role of subjectivity, his insistence that physics can only speak in terms of observables leaves open the question of how far quantum theory describes nature as it is, apart from the conditions of our access to it. In other words it calls the ideal of complete objectivity into question. -

JuanZu

382I take your point that we should not confuse subjectivity with the role of the measuring apparatus. Of course it is the detector, not personal awareness, that interacts with the system. But the question that persists — and this is what makes the problem metaphysical — is: why does the interaction only count as a measurement when it enters the domain of observables, that is, when it becomes information available to us? — Wayfarer

JuanZu

382I take your point that we should not confuse subjectivity with the role of the measuring apparatus. Of course it is the detector, not personal awareness, that interacts with the system. But the question that persists — and this is what makes the problem metaphysical — is: why does the interaction only count as a measurement when it enters the domain of observables, that is, when it becomes information available to us? — Wayfarer

Once we naturalise the measuring device, it becomes something external to subjectivity. In this sense, measurement is a natural process like any other in nature. It should be noted that our quantum physics experiments require isolation. That is why the measuring device breaks that isolation and what is in quantum coherence becomes decoherent. But that apparatus is part of the experiment's environment! This means that the measuring apparatus and non-subjective reality are identified.

For me, this is a sufficient explanation that frees us from possible idealistic interpretations of quantum physics. Measuring is a natural act that is identified with the external world. -

JuanZu

382

JuanZu

382

I wouldn't say they are unnatural. Rather, improbable. Something like a measuring device is not out of this world. That is, there is a reason why there is interaction with quantum states. A reason why they can be measured. There is an ontological continuity between the measuring device and that which is measured. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point isn’t that instruments are “out of this world,” but that they’re not just neutral parts of nature either. They’re artifacts manufactures to register specific events in a communicable and repeatable manner. That means they embody our intentions, and precisely there the epistemic cut reappears — between what simply happens in nature and what is meaningful as information. There's a really fundamental ontological divide there which you can't simply paper over by declaring instruments 'natural'.

Wayfarer

26.2kThe point isn’t that instruments are “out of this world,” but that they’re not just neutral parts of nature either. They’re artifacts manufactures to register specific events in a communicable and repeatable manner. That means they embody our intentions, and precisely there the epistemic cut reappears — between what simply happens in nature and what is meaningful as information. There's a really fundamental ontological divide there which you can't simply paper over by declaring instruments 'natural'. -

J

2.5kBut what was 'real' to the scholastics, was not the physical world as such. When we say “physical world,” we usually mean what modern physics investigates—matter, energy, and their interactions. But for St. Thomas, there was no such concept as a self-subsisting “physical” realm. — Wayfarer

J

2.5kBut what was 'real' to the scholastics, was not the physical world as such. When we say “physical world,” we usually mean what modern physics investigates—matter, energy, and their interactions. But for St. Thomas, there was no such concept as a self-subsisting “physical” realm. — Wayfarer

I'm sure this is true. But if we could translate our concepts for St. Thomas -- and I see no reason why he wouldn't be able to understand us -- and ask him whether, when we see an apple, we are seeing something that is really there, more or less as presented to our senses, wouldn't he say yes? That is the sort of realism I was suggesting the Scholastics accepted.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- What is the difference between subjective idealism (e.g. Berkeley) and absolute idealism (e.g. Hegel

- What does this philosophical woody allen movie clip mean? (german idealism)

- Idealism and "group solipsism" (why solipsim could still be the case even if there are other minds)

- Rationalism or Empiricism (or Transcendental Idealism)?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum