-

Michael

16.9kDo you mean the word-string "snow being green" or something else? — bongo fury

Michael

16.9kDo you mean the word-string "snow being green" or something else? — bongo fury

Something else.

Snow being green isn't a sentence. Snow being white isn't a sentence. Vampires being immortal isn't a sentence. -

bongo fury

1.8kSomething else.

bongo fury

1.8kSomething else.

Snow being green isn't a sentence. Snow being white isn't a sentence. Vampires being immortal isn't a sentence. — Michael

Do you mean that some alleged (truth-making) non-word-string corresponding to or referred to by the word-string "snow being white", or indeed by the word-string "snow is white", isn't a sentence?

I think that was @Luke's point, but fair enough. So you would clarify thus:

Although there may be times, like with (a), where the consequentisdoes correspond to a fact, — Michael

?

Or are you still unsure whether it's correct to call a (truth-bearing) sentence or proposition a fact? -

Michael

16.9kDo you mean that some alleged (truth-making) non-word-string corresponding to or referred to by the word-string "snow being white", or indeed by the word-string "snow is white", isn't a sentence? — bongo fury

Michael

16.9kDo you mean that some alleged (truth-making) non-word-string corresponding to or referred to by the word-string "snow being white", or indeed by the word-string "snow is white", isn't a sentence? — bongo fury

I mean exactly what I said; that snow being green isn't a sentence. What I'm unsure of is what snow being green is.

So you would clarify thus:

Although there may be times, like with (a), where the consequentisdoes correspond to a fact, — bongo fury

Here's a sentence:

a) Joe Biden is President

I would say that the subject of the sentence is a person. I wouldn't say that the subject of the sentence corresponds to a person.

So here's another sentence:

b) "snow is white" is true iff snow is white

Perhaps the consequent of (b) is a fact, similar to how the subject of (a) is a person. -

bongo fury

1.8kI wouldn't say that the subject of the sentence corresponds to a person. — Michael

bongo fury

1.8kI wouldn't say that the subject of the sentence corresponds to a person. — Michael

Well I would recommend it, in any discussion of semantics, as "subject" is notoriously ambiguous between word and object, and often clarified for example by use of "grammatical subject" versus "logical subject". (Which at least serves to flag up the issue.)

I mean exactly what I said; that snow being green isn't a sentence. — Michael

If you don't see how my clarification might prevent people from thinking you were talking about the word string "snow being green" not being a sentence, then I must suspect you are becoming enchanted by systematic equivocation. -

Michael

16.9kIf you don't see how my clarification might prevent people from thinking you were talking about the word string "snow being green" not being a sentence... — bongo fury

Michael

16.9kIf you don't see how my clarification might prevent people from thinking you were talking about the word string "snow being green" not being a sentence... — bongo fury

Given that I didn't use quotation marks it should be obvious. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention.

a) snow being green isn't a sentence

b) "snow being green" isn't a sentence

These mean different things. That should be obvious to any competent English speaker. -

Sam26

3.2kI didn't want to reply in your thread, since it's an exegesis, so I replied here.

Sam26

3.2kI didn't want to reply in your thread, since it's an exegesis, so I replied here.

Banno said the following:

"Tarski took that notion and applied it to truth, and showed that, just as there are always theorems that cannot be proved, there cannot be a definition of truth within that language. Another language is needed, or at least an extension of the language.

The proof takes a first-order language with "+" and "=", and assigns a Gödel number to every deduction, as in the incompleteness proofs. It then finds a Gödel number for a definition of truth, and shows that it is not amongst the list of Gödel numbers of the deductions. Hence, that definition is not amongst the deductions of the language.

In plain language, an arithmetic system cannot define arithmetic truth, for itself.

Hence it was apparent to Tarski that in order to talk about truth, one needed an object language and a metalanguage. This is what he developed in his definition of truth."

There seems to be something amiss here, viz., applying Gödel's incompleteness theory to the definition of truth. Tarski thinks that since there are theorems that cannot be proven within a system, that he can use this idea to create a meta-language, and thereby create a definition of truth outside our ordinary language (be it English, Italian, Spanish, etc). However, the question is, is this a misunderstanding of Gödel's theory. Gödel's theories apply to statements about number theory, so any mathematical theory that doesn't include statements about number theory are excluded from Godel's theories. So, there are limits to what Gödel is proposing. It seems a bit of a stretch, to say the least, to think Gödel incompleteness theory can be applied to the meaning of truth. I think that Tarski is stretching Godel a bit too far. -

bongo fury

1.8kThat should be obvious to any competent English speaker. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention. — Michael

bongo fury

1.8kThat should be obvious to any competent English speaker. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention. — Michael

I disagree. Never mind.

Perhaps the consequent of (b) is a fact, similar to how the subject of (a) is a person. — Michael

Well sure, but a consequent is a sentence (or proposition). So you now reject

I don't think it correct to say that the proposition is the fact. — Michael

as tiresome pedantry? Ok. Since you don't claim to be denying corresponding truth-makers for whole sentences, I shall be less suspicious of equivocation.

It is not a fact that snow is green. — Michael

Without truth-makers for whole sentences, this is unproblematic. It just means that " 'snow is green' is true" and "snow is green" share false instead of true as their common truth value.

And if you want more (rather than pure deflation) try

"True" applies to "snow is green" iff "green" applies to snow.

This talks about practices of classification.

c) unicorns are green

"True" applies to "unicorns are green" iff [more careful formulation, still false]

Fiction is literally false. Figurative truth translates usefully into literal truth about second-order extensions.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/556693 -

Michael

16.9kTarski does say in his 1933 paper:

Michael

16.9kTarski does say in his 1933 paper:

For the reasons given in the preceding section I now abandon the attempt to solve our problem for the language of everyday life and restrict myself henceforth entirely to formalized languages. These can be roughly characterized as artificially constructed languages in which the sense of every expression is unambiguously determined by its form.

So perhaps Tarski is right in referencing Godel. What's wrong is interpreting Tarski as having said something about the meaning of "true" in our natural language (at least with respect to his 1933 paper). -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Tarski's star student, Richard Montague, denied there was any difference between formalized languages and natural languages, and considered linguistics a branch of mathematics. For what it's worth. -

Michael

16.9kSomething else worth mentioning from The Semantic Conception of Truth:

Michael

16.9kSomething else worth mentioning from The Semantic Conception of Truth:

In fact, the semantic definition of truth implies nothing regarding the conditions under which a sentence like (1):

(1) snow is white

can be asserted. It implies only that, whenever we assert or reject this sentence, we must be ready to assert or reject the correlated sentence (2):

(2) the sentence "snow is white" is true.

Thus, we may accept the semantic conception of truth without giving up any epistemological attitude we may have had; we may remain naive realists, critical realists or idealists, empiricists or metaphysicians – whatever we were before. The semantic conception is completely neutral toward all these issues. -

RussellA

2.7kYou present an account of institutional facts, in which the direction of fit is word-to-world. and then jump to the non sequitur that all utterances are of this sort. They are not. — Banno

RussellA

2.7kYou present an account of institutional facts, in which the direction of fit is word-to-world. and then jump to the non sequitur that all utterances are of this sort. They are not. — Banno

I agree that most of the time I accept the names given to things by society, such as ships, tables, governments, etc. However there are occasions when there are no existing words that fit the bill. For example, to make a philosophic point, two years ago I made the performative utterance: "a peffel is part my pen and part The Eiffel Tower".

I agree that most of the time the direction of fit is world to word, but there are occasions whereby word to world is also required.

===============================================================================

What is truth ?

I perceive in my world my pen and the Eiffel Tower. My pen and the Eiffel Tower are facts in my world.

Along the lines of the Tractatus, it is immaterial as to whether I believe in Idealism or Realism. Regardless, I know that my pen and the Eiffel Tower are facts in my world.

In a performative utterance, I name my pen and the Eiffel Tower a "peffel". A performative utterance is in a sense a christening, such as "I name this baby Horatio". I record my performative utterance in a (metaphorical) dictionary.

Before the performative utterance, in my world are the facts my pen and the Eiffel Tower. After the performative utterance, in my world are the facts a peffel, my pen and the Eiffel Tower.

In Searle's terms, a performative utterance is an Institutional activity. A performative utterance creates new Institutional facts, whether it is the fact that the bishop always stays on the same coloured squares, or a peffel is part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower. Institutional facts require a social obligation, whether I am obliged to move the bishop diagonally, or my listener is obliged to acknowledge the sense of the word peffel when used in conversation.

Under what conditions is the statement "a peffel is part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower" true ? Its truth value can only be known if its meaning is first known. The meaning of a "peffel" may be discovered in the dictionary, such that "a peffel is part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower". Knowing the meaning of a "peffel", and knowing that my pen and the Eiffel Tower are facts in my world, the statement "a peffel is part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower" is true.

It is said that dictionaries are not all that useful as meaning changes, but (metaphorical) dictionaries are foundational to knowing the nature of truth. It is true that definitions may change with time, in that Art as Postmodernism didn't exist before the 1960's, but as definitions change, our knowing what is true changes. Our knowledge of what is truth is not a fixed thing.

Under what conditions is the statement "A is X and Y" true. First, its meaning must be known. The meaning of "A" may be discovered in the dictionary, such that "A is X and Y". Knowing its meaning, and knowing that X and Y are facts in my world - the statement "A is X and Y" is true.

Therefore, a linguistic statement is true when, not only, the subject has been defined in a performative utterance as having the properties given in the predicate, but also, the predicate exists as facts in the world.

IE, rather than "snow is white" is true iff snow is white, I would suggest that "snow is white" is true iff not only has "snow" been defined as having the property "white" but also snow is white.

===============================================================================

You present an argument that language is arbitrary, which in a sense it is, then jump to the non sequitur that truth is relative — Banno

Some aspects of language can be arbitrary, and other aspects can be relative.

I perceive something white in my world. I have a free choice as to what I name it. In a performative utterance I give it a name, I christen it "X". In a sense, my choice of "X" is arbitrary.

As regards "the truth is what I say it is", truth refers to the statement "snow is X" rather than the fact in the world that snow is X.

Situation one: I christen "snow" as "white".

"Snow is white" is true iff "snow" has been defined as "white" and snow is white.

Situation two: I christen "snow" as "black"

"Snow is black" is true iff "snow" has been defined as "black" and snow is white.

In a sense, the truth of the statement is relative to my arbitrary choice of the name I use when christening what I have perceived in my world. -

Tate

1.4kSomething else worth mentioning from The Semantic Conception of Truth:

Tate

1.4kSomething else worth mentioning from The Semantic Conception of Truth:

In fact, the semantic definition of truth implies nothing regarding the conditions under which a sentence like (1):

(1) snow is white

can be asserted. It implies only that, whenever we assert or reject this sentence, we must be ready to assert or reject the correlated sentence (2):

(2) the sentence "snow is white" is true.

Thus, we may accept the semantic conception of truth without giving up any epistemological attitude we may have had; we may remain naive realists, critical realists or idealists, empiricists or metaphysicians – whatever we were before. The semantic conception is completely neutral toward all these issues. — Michael

:up: -

RussellA

2.7kAn interesting puzzle, though, is how, relative to a language game, truth can be absolute as well as relative. — bongo fury

RussellA

2.7kAn interesting puzzle, though, is how, relative to a language game, truth can be absolute as well as relative. — bongo fury

Given the Sorites Paradox, we have a heap of sand. A heap is defined as "a large number of". Large is defined as considerable. Considerable is defined as large. Definitions become circular.

The word "heap" is as vague as any concept - love, hate, government, the colour red, tables, etc. Yet we have one word for something that is imprecise, for something vague yet is recognizable.

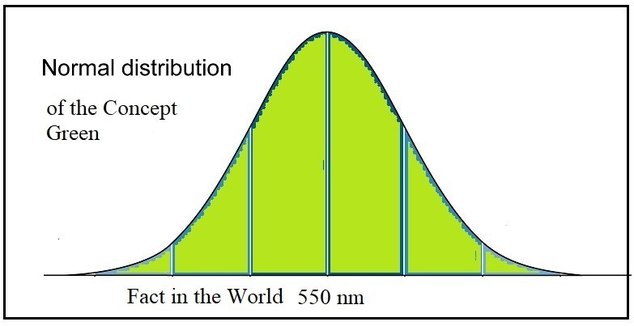

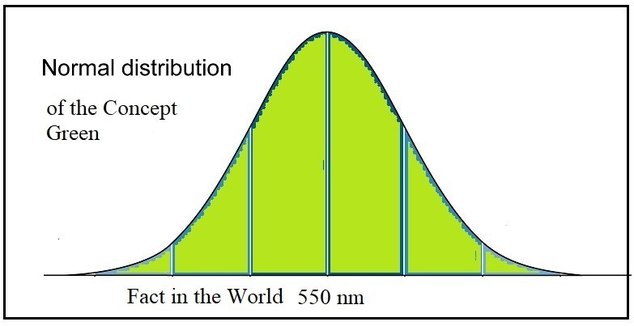

I suggest that the brain's ability to fix a single name to something that is variable is fundamentally statistical. For example, I am certain I see the colour green, I believe it is green, I am probably seeing green, I think it is green, it could be green, it may be green. Such statistically-based concepts could be readily programmed into a computer. Complex concepts may be developed from a set of simple concepts.

-

creativesoul

12.2kIt doesn't seem that either (3) or (5) can fully account for self-referential sentences. — Michael

I think the T schema only works with sentences that begin with a universal quantifier. I cannot make much sense of my saying that, but it seems to me that I'm just repeating something Davidson and Quine said during a discussion between them about Tarski's definition and disquotation model. -

bongo fury

1.8kA heap is defined as "a large number of". Large is defined as considerable. Considerable is defined as large. Definitions become circular. — RussellA

bongo fury

1.8kA heap is defined as "a large number of". Large is defined as considerable. Considerable is defined as large. Definitions become circular. — RussellA

Yes, although the circularity perhaps only reflects the fact that definitions are unnecessary. The game asks for judgements, but not reasons.

I suggest that the brain's ability to fix a single name to something that is variable is fundamentally statistical. — RussellA

Fair enough. My interest is more in the linguistic community's ability to fix the name. Recent research in the area is indeed statistical.

Such statistically-based concepts could be readily programmed into a computer. — RussellA

Or, even better, developed by evolutionary algorithms that simulate cooperative language games. The results are indeed similar to your picture, or mine here:

But, as such, they all fail the sorites test, which requires some perfectly absolute intolerance, as well as tolerance. Is my gripe. As discussed.

I mentioned this to you because you seemed to be wrestling with the tension between individual (Humpty Dumpty) judgements and general norms. And I think that's what the sorites puzzle is about. As your reply maybe supports. -

Janus

18kI don't quite understand your use of "contingent" here. If you ask someone to tell the truth about something that happened, and the person gives you an honest reply, there is no necessity which would allow you to conclude that the person's reply is an accurate portrayal of what happened. The person might have a faulty memory, as we all do to some extent. This produces the need to allow for all sorts of varying degrees of what you call accuracy, depending on what features of the particular occurrence you are asking the person to describe. — Metaphysician Undercover

Janus

18kI don't quite understand your use of "contingent" here. If you ask someone to tell the truth about something that happened, and the person gives you an honest reply, there is no necessity which would allow you to conclude that the person's reply is an accurate portrayal of what happened. The person might have a faulty memory, as we all do to some extent. This produces the need to allow for all sorts of varying degrees of what you call accuracy, depending on what features of the particular occurrence you are asking the person to describe. — Metaphysician Undercover

What could a truthful account of an event be if not an accurate portrayal of what happened? The question is not about how we can know whether an account is truthful or not. Taking your radical skeptical line we could never know. I could have witnessed the same event someone is giving an account of, and so be in a position to judge whether the account were truthful or not, but according to your line of reasoning, my memory might be faulty, which means I could never be in a position to judge the truthfulness of any account of anything.

But the point is we must understand what it would mean to be able to judge whether some account were truthful or not, in order to be skeptical about our ability to do so. -

hypericin

2.1kThree things must be distinguished:

hypericin

2.1kThree things must be distinguished:

1. The spoken/written sentence

2. The proposition the listener/reader derives from 1

3. The state of affairs relevant to 2.

Truthhood obtains to 2 alone. 1 is inherently ambiguous, and is not in itself true or false.

Are scrawlings on a page or vibrations in the air true? Absurd, this is an obvious category error. They are symbols, only their interpretations can be true or false. -

Janus

18k"The whole is greater than the sum of the parts" is true ≡ The whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Janus

18k"The whole is greater than the sum of the parts" is true ≡ The whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

To what does this correspond?

"Frodo walked in to Mordor" is true ≡ Frodo walked in to Mordor.

To what does this correspond?

"Frodo walked in to Sydney" is true ≡ Frodo walked in to Sydney.

To what does this correspond?

"No bachelor is married" is true ≡ No bachelor is married.

To what does this correspond?

"All bachelors are married" is true ≡ all bachelors are married.

To what does this correspond?

"This sentence is false" is true ≡ this sentence is false

To what does this correspond?

Ands so on. By the time you give an account of correspondence, there is nothing left. — Banno

The answer is that the whole formulations do not correspond to anything, but the underlying logic is that the quoted sentence on the left in each case corresponds to an actuality it represents, as it is used on the right, if the sentence is true.

"The whole is greater than the sum of its parts" corresponds, if true, to the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

"Frodo walked into Mordor" corresponds to Frodo walking into Mordor, as depicted in Lord of the Rings.

"Frodo walked into Sydney" does not correspond to anything since the fictional character Frodo was never depicted by his creator as walking into Sydney.

You get the picture, correspondence is most easily understood, it is the model we all use every day and the one exemplified by the T-sentence..You'll only confuse yourself if you try to overthink it. -

hypericin

2.1kP is true is just fancy talk for P. — Pie

hypericin

2.1kP is true is just fancy talk for P. — Pie

This is just not true. P paints a propositional picture. By stating P, in some languages and contexts, it might be assumed that the same speech act is also affirming the propositional picture as being true(whatever that means). In other languages or contexts it might be assumed that P is short for "consider P", "it might be that P", etc. -

Moliere

6.5kWhen we talk about truth, we're referring to what people believe. Some theories provide a better answer to the question of truth than other theories. I happen to think the correspondence theory works well.

Moliere

6.5kWhen we talk about truth, we're referring to what people believe. Some theories provide a better answer to the question of truth than other theories. I happen to think the correspondence theory works well.

Usually when people agree that a particular statement is true, they agree on some fact of the matter. In some cases we're just speculating about the truth, or we are just giving an opinion about what we think is true. In still more cases we may express a theory that X is true, as Einstein did with the general theory of relativity. It wasn't until Eddington verified Einstein's theory that we knew the truth of the matter. Here of course truth is connected with knowledge, not just an opinion or speculation.

If you want to learn what truth is, then study how the concept is used in a wide variety of situations, i.e., in our forms of life. Think about people disagreeing about political or economic views, they're disagreeing about the facts associated with these views. Most don't know enough to recognize what facts make their belief true or false, so their disagreeing over opinions, and some are willing to kill over their opinions, but I digress.

What's true can also refer to possible worlds, and to works of fiction. So, there can be facts associated with things that aren't even real. Anything we do is associated with some fact, and as such it can be associated with what we believe.

There is definitely the concept of truth, so it's not as though the concept doesn't exist, or that it doesn't have a place within our various linguistic contexts.

Insight is gained by looking carefully at the various uses of these concepts. The problem is that many people want exactness where there is none, at least not in some absolute across the board sense. There are some absolutes when it comes to truth, but those absolutes are relative to a particular context. — Sam26

I agree with your method, but I think it takes me elsewhere. I like where you start:

"When we talk about truth, we're referring to what people believe. "

But then I have to say that "better" or "well" looks too close to "true" :D -- As in, correspondence itself is also a fact, and our statements about correspondence are true due to that fact. That's consistent at least! But if it's not that, I wonder what value that isn't truth decides between the theories for yourself?

I think people agree to a fact, but I've been saying there's not much of a difference between a fact and a true statement -- that they are one and the same, and the story of correspondence is what creates a picture of some fact corresponding to the meaning of a statement believed. In the same way that we can say true things about Harry Potter, so we can say true things about truth.

Sometimes a person might be suspicious and go test a claim -- are the plums in the icebox after all? Here the method is "look in the icebox", and depending upon what you see you'll ascertain whether the person spoke truly or falsely. The meaning of true or false doesn't change because that's been well-entrenched by several hundred years of use. There's a definite history to the predicate "...is true". But our belief about the sentence "There are plums in the icebox" will change depending upon what we see. We will evaluate it to be true or false.

Was it true or false beforehand? Yes. That's exactly how we use the words "...is true" and "...is false". In the game of truth-telling, it's understood that the person can lie -- that what they say could turn out to not be the case if we go and check somehow. So we apply that game to individual statements and invent a metaphysics around it. But it started out as a social practice. It started with others, before myself. -

Banno

30.6kNot exactly. — Michael

Banno

30.6kNot exactly. — Michael

See

We have material adequacy:

For any sentence p, p is true if and only if ϕ

and we tie meaning down by sticking to one sentence, so that the meaning cannot be ambiguous. We name the sentence on one side, and use it on the other.

"p" is true if and only if p

...and hey, presto, we have a definition of truth. — Banno

It's not Tarski who pulls this stunt, but others after his work. -

Banno

30.6k"Snow is white" is not a fact, because facts are things in the world, and so while "snow is white" represents a fact, it is not a fact.

Banno

30.6k"Snow is white" is not a fact, because facts are things in the world, and so while "snow is white" represents a fact, it is not a fact.

— Banno

So this is what you now say.

"The cat is on the mat" is true ≡ The cat is on the mat

The thing on the right is a fact.

— Banno

In light of your new reflections, then, do you endorse the following clarification?

"The cat is on the mat" is true ≡ The cat is on the mat

The thing represented by the sentence on the right is a fact. — bongo fury

I dunno, Bong. You seem to me to just be repeating an argument I've already addressed a couple of times.

And it seems that others (@Michael) have tried to make the same point to you.

The thing represented by the sentence on the right is a fact. — bongo fury

It's clear that the thing on the right is not the name of a fact. Names do not have truth values.

AND again,

I. "Snow is white" is not a fact, because facts are things in the world, and so while "snow is white" represents a fact, it is not a fact.

II. That snow is white is not a fact, because facts are things in the world, and so while that snow is white represents a fact, it is not a fact. — Banno

You seem to be denying that, that snow is white is a fact. You want to say instead that, that snow is white only represents a fact. And I think that's not right.

Yours is perhaps the move criticised by Davidson in On the very idea.... -

Banno

30.6kI didn't want to reply in your thread, since it's an exegesis, so I replied here. — Sam26

Banno

30.6kI didn't want to reply in your thread, since it's an exegesis, so I replied here. — Sam26

Cheers, yes, that's the idea.

So Tarski's indefinability theorem has an odd conclusion, and yet it is an accepted, proven piece of formal logic.

Keep in mind that it applies to axiomatic systems. Tight little constructs that keep everything overly simple.

I think of such systems as sub-systems within natural languages. So we have an axiomatic system that cannot talk about the truth of it's sentences, a metalanguage that can talk about the truths of the object language but not about it's won truths, a meta-metalanguage that can talk about the truths of the object language and the metalanguage but not itself, and so on. And a natural language that can talk about all of them and more.

And this is where Gödel and derangement of epitaphs come in to play. Any rule can and will be broken to grow the language. -

Banno

30.6kThat should be obvious to any competent English speaker. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention.

Banno

30.6kThat should be obvious to any competent English speaker. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention.

— Michael

I disagree. Never mind. — bongo fury

Perhaps that is the problem. -

Michael

16.9kTarski does what you say only he makes it clear that this doesn't count as the definition of truth:

Michael

16.9kTarski does what you say only he makes it clear that this doesn't count as the definition of truth:

(T) X is true if, and only if, p.

We shall call any such equivalence (with 'p' replaced by any sentence of the language to which the word "true" refers, and 'X' replaced by a name of this sentence) an "equivalence of the form (T)."

Now at last we are able to put into a precise form the conditions under which we will consider the usage and the definition of the term "true" as adequate from the material point of view: we wish to use the term "true" in such a way that all equivalences of the form (T) can be asserted, and we shall call a definition of truth "adequate" if all these equivalences follow from it.

It should be emphasized that neither the expression (T) itself (which is not a sentence, but only a schema of a sentence) nor any particular instance of the form (T) can be regarded as a definition of truth. We can only say that every equivalence of the form (T) obtained by replacing 'p' by a particular sentence, and 'X' by a name of this sentence, may be considered a partial definition of truth, which explains wherein the truth of this one individual sentence consists. The general definition has to be, in a certain sense, a logical conjunction of all these partial definitions. — The Semantic Conception of Truth

Which authors disagree with Tarski? -

Banno

30.6kIt's not a disagreement, but a seperate argument.

Banno

30.6kIt's not a disagreement, but a seperate argument.

Tarski defines truth in terms of meaning, using all that satisfaction stuff.

But in this:

"p" is true ≡ p

...there can be no doubt that the meaning of p is held constant; that p is used on the right and mentioned on the left. (p cannot mean something other than it means.) So there is no need for satisfaction, or any other theory of meaning.

Hence it holds meaning constant, and so gives a definition of Truth. -

Michael

16.9kAnd again, from the 1933 paper:

Michael

16.9kAnd again, from the 1933 paper:

(5) for all p, 'p' is a true sentence if and only if p.

But the above sentence could not serve as a general definition of the expression 'x is a true sentence' because the totality of possible substitutions for the symbol 'x' is here restricted to quotation-mark names.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum