-

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Thanks. That summary is in agreement my own understanding of the Real/Ideal and Phenomenal/Noumenal dichotomy. But my question was about your characterization of Kant's "equivocation" of that neat two-value division of the knowable world*1. Of course, in philosophical discourse, that "interplay" can get complicated, to the point of paradox.Within this context, 'noumenal' means, basically, 'grasped by reason' while sensible means 'grasped by thesense organs'. In hylomorphic dualism, this means that nous apprehends the form or essence of a particular - what is really is - and the senses perceive its material appearance. That's the interplay of 'reality and appearance'. Again from the article on Noumenon: — Wayfarer

I have the general impression that both Plato (real/ideal) and Aristotle (hyle/morph) also divided the philosophical arena of discourse into Sensory Observations and Rational Inference. So, I was wondering if Kant had posited a different analysis of the Things & Dings that philosophers elaborate & logic-chop into such tiny bits of meaning. Physical things can be reduced down to material atoms by dissection. And Metaphysical dings (ideas about things), presumably can be analyzed down to conceptual atoms. But does the distinction between Physical & Meta-Physical remain in effect?

That said, your comment about Kant's "confusing equivocation" raised the question in my simple mind : is there a third (non-quibbling) Ontological category of knowledge, other than Phenomenal (sensory) & Noumenal (inference) : perhaps Intuition (sixth sense) that bypasses both paths to knowledge? Is a ding an sich Phenomenal or Noumenal or something else? :smile:

*1. Quote from this thread :

"I would agree with that description, although not with the equivocation with ‘ding an sich’. That is owed to Kant’s confusing equivocation of ‘thing in itself’ with ‘noumenal’ which actually have two different meanings."

___ Wayfarer

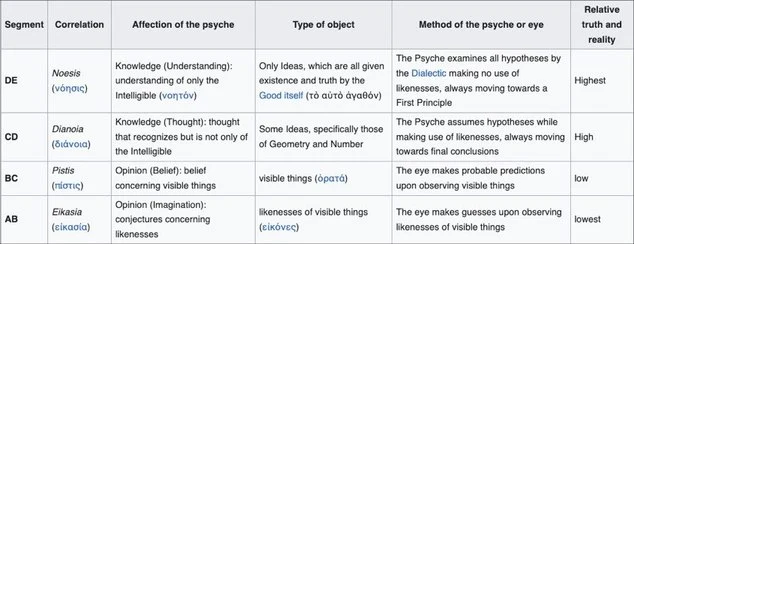

PS___ Post posting, I found this summary of Ways of Knowing. I don't know where it came from, or if it's even relevant to Aristotle's Metaphysical Ontology.

-

Paine

3.2k** ‘Pure actuality’ can be traced back to Parmenides vision of ‘what is’ as being above or beyond the change and decay of concrete particulars. As modified first by Plato and then Aristotle, ideas are eternal and changeless, in which particulars ‘participate’. Unlike Plato, Aristotle did not posit a separate realm of Forms but argued that the form and matter coexist in the same substance. However, he maintained that the highest forms of being, such as the unmoved mover, are pure actuality, embodying eternal and changeless existence. — Wayfarer

Paine

3.2k** ‘Pure actuality’ can be traced back to Parmenides vision of ‘what is’ as being above or beyond the change and decay of concrete particulars. As modified first by Plato and then Aristotle, ideas are eternal and changeless, in which particulars ‘participate’. Unlike Plato, Aristotle did not posit a separate realm of Forms but argued that the form and matter coexist in the same substance. However, he maintained that the highest forms of being, such as the unmoved mover, are pure actuality, embodying eternal and changeless existence. — Wayfarer

It is not only that "form and matter coexist in the same substance." The nature of change in the realm of coming to be and passing away is different than movement in eternal things because the latter are not subject to coincidental causes. The relationship between the 'acting' and the 'acted upon' requires a

specific understanding of the actual and the potential as emerge in beings:

The cause of movement’s seeming to be indefinite, though, is that it cannot be posited either as a potentiality of beings or as an activation of them. For neither what is potentially of a certain quantity nor what is actively of a certain quantity is of necessity moved, and while movement does seem to be a sort of activity, |1066a20| it is incomplete activity. But the cause of this is that the potentiality of which it is the activation is incomplete. And because of this it is difficult to grasp what movement is, since it must be posited either as a lack or as a potentiality or as an activity that is unconditionally such. But evidently none of these is possible. And so the remaining option is that it must be what we said, both an activity and not an activity |1066a25| in the way stated, which, though difficult to visualize, can exist. And that movement is in the movable is clear, since movement is the actualization of the movable by what can move something. And the activation of what can move something is no other. For there must be the actualization of both, since it can move something by having the potentiality to do so, and it is moving it by being active. But |1066a30| it is on the movable that the mover is capable of acting, so that the activation of both alike is one, just as the intervals from one to two and from two to one are the same, or as are the hill up and the hill down, although the being for them is not one. And similarly in the case of the mover and the moved. — Metaphysics, Kappa 9, translated by CDC Reeve

So, this "difficult to visualize" aspect of matter as potential being returns us to the beginning of the book:

These people, then, |985a10| as we say, evidently latched on to two of the causes we distinguished in our works on nature, namely, the matter and the starting-point of movement.91 But they did so vaguely and in a not at all perspicuous way, like untrained people in fights.92 For these too, as they circle their opponents, often strike good blows, but |985a15| they do not do so in virtue of scientific knowledge, just as the others do not seem to know what they are saying, since they apparently make pretty much no use of these causes, except to a small extent. — ibid. Alpha 4 -

Wayfarer

26.2khat said, your comment about Kant's "confusing equivocation" raised the question in my simple mind : is there a third (non-quibbling) Ontological category of knowledge, other than Phenomenal (sensory) & Noumenal (inference) : perhaps Intuition (sixth sense) that bypasses both paths to knowledge? — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2khat said, your comment about Kant's "confusing equivocation" raised the question in my simple mind : is there a third (non-quibbling) Ontological category of knowledge, other than Phenomenal (sensory) & Noumenal (inference) : perhaps Intuition (sixth sense) that bypasses both paths to knowledge? — Gnomon

In esoteric philosophy there are said to be forms of gnosis or Jñāna or direct insight. They're very difficult to assess for pretty obvious reasons, as esoteric philosophy is, well, esoteric. I sometimes have the intuition that there is a missing element in Kant's philosophy corresponding to an absence of this kind of insight, but I'm not able to really pinpoint or articulate it as after all we're dealing here with some of the most difficult questions of philosophy.

That table is from the wikipedia article on ‘the analogy of the divided line’ in the Republic. It is in the section adjacent to the Parable of the Cave. It’s certainly relevant, but it was Plato’s rather than Aristotle’s.

Thanks, that is a difficult passage, although something that comes to mind is Werner Heisenberg's appeal to Aristotle's 'potentia' as a way to understand the nature of the sub-atomic realm. See Quantum Mysteries Dissolve if Possibilities are Realities (although I won't comment further for fear of dragging the thread into the insoluble conundrums of modern physics, other than to say that said conundrums show that metaphysics is far from dead.) -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kAgain, the point is that we are discussing efficient, not final, causality and digressing into final causality only leads to confusion. — Dfpolis

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kAgain, the point is that we are discussing efficient, not final, causality and digressing into final causality only leads to confusion. — Dfpolis

The problem though, is that "house", referring to something not yet built, is a final cause. You refuse to acknowledge this, and keep trying to portray this final cause, the goal of building a house, a house being built, as an efficient cause. So your attempt to simplify the intentional action of building, to describe it as consisting solely of efficient causation, when final causation is obviously involved, produces a false representation of the activity.

"A house being built" refers to a project, an end, a final cause. The builder is affected by that project and has the passion to build. Therefore the builder building is the effect of that final cause which is the project of "the house" which is being built.

Since you apparently don't like this question, it occurs to me to ask you just what exactly you think a cause is for Aristotle. While I suppose you must know, it's not clear in your usage. And I think maybe you get it mixed up with a modern understanding of the word. Give it a try; doesn't have to be a treatise; a paragraph or two should be adequate for present purpose. — tim wood

I've grown accustomed to ignoring your questions which appear to be completely irrelevant. If you would explain to me why you are asking something which looks really stupid, like do I believe it is possible to build a house, and why you think this is relevant, I might see the need to answer it. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kit occurs to me to ask you just what exactly you think a cause is for Aristotle. — tim wood

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kit occurs to me to ask you just what exactly you think a cause is for Aristotle. — tim wood

I will answer this one. Aristotle describe four principal ways "cause" is used, material, formal, efficient, and final. Also he outlined two accidental uses, which are not to be understood as proper causes. These are luck and chance. -

Dfpolis

1.3k

Dfpolis

1.3k

It comes from Plato. In the Republic (509d–511e) he lays out the taxonomy of thought using the analogy of a divided line. The line is first divided into δόξα (opinion), reflecting the sensible world, and ἐπιστήμη (knowledge), reflecting the intelligible world. Each half is subdivided on the basis of clarity. Opinion is sub-divided into εἰκασία (conjecture/illusion), reflecting shadows and reflected images, and πίστις (belief/science), reflecting mutable bodies. Knowledge is partitioned into discursive thought (διάνοια) and understanding (νόησις). Discursive thought uses “images” (sensible reality, e.g. as in geometry) while understanding does not (510b).I found this summary of Ways of Knowing — Gnomon -

Wayfarer

26.2kRegarding the significance of teleology and its place in Aristotle's metaphysics, I happened on a very succinct explanation in a video talk by cognitive scientist Lisa Feldman Barrett. She simply says that teleology is 'an explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose which they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise'. That says a lot in very few words, as it demonstrates the sense in which reason also encompasses purpose for Aristotle, in a way that it does not for modernity.

Wayfarer

26.2kRegarding the significance of teleology and its place in Aristotle's metaphysics, I happened on a very succinct explanation in a video talk by cognitive scientist Lisa Feldman Barrett. She simply says that teleology is 'an explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose which they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise'. That says a lot in very few words, as it demonstrates the sense in which reason also encompasses purpose for Aristotle, in a way that it does not for modernity. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe efficient cause is his skills as a builder, the skills themselves and the skills as he possesses them, so yes, informally, he is. — tim wood

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe efficient cause is his skills as a builder, the skills themselves and the skills as he possesses them, so yes, informally, he is. — tim wood

"Efficient cause" refers to the particular action which leads to the existence of the item. But "the skills" refers to something general. Therefore the skills are not the efficient cause.

So the efficient cause of the house is the property, or art or skill, of the builder as a builder. Material cause not the material itself, but the property or capacity - or passion - of the material to be worked in an appropriate way. Formal, not the plans, but the quality of the plans which makes it possible to build from them. Final, the property, or capacity, of the thing built to be used as intended. — tim wood

Sorry tim, I just can't understand this at all. It's not the Aristotle that I know.

Let's try this: In as much as you say the house is the goal, the final cause, and you imply that before it is, it isn't, what then is the builder building? — tim wood

The builder is building a house. But a material thing in the condition of becoming, being created or produced, has no material existence until after it is produced. These are some of the issues which Aristotle dealt with in his discussions of "change", the difference between the prior condition and the posterior condition.

And there a regression here, because the implication - your implication - is that anything built as a final cause, not existing before it exists, cannot be built. — tim wood

The final cause is the house as a goal, an end, the intent, that is how Aristotle describes final cause, as "the end", and this signifies what we call the goal or objective. Take a look at Aristotle's example, the final cause of the person walking is the goal of health.

The goal, or end is the cause of the person's activities. The activities themselves are the efficient causes, as the means to that end. The person has choice, not only in the decision as to which ends are desired, but also in the determination of the means (efficient causes) required to produce the end. However, since the specified means are often seen as the only way to produce the desired end, there is often a logical necessity linking the means with the end.

So if (from above) the window was broken by Bob, Bob had been affected by the window and had a passion to break it? — tim wood

In the case of an intentional act, that is almost what I said, but not quite. Bob is affect by the goal, or end, which is to have the window broken. So he breaks it. His action is a passion caused by that goal or end (not by the window itself, but the goal of breaking it), as his action is the effect of that final cause. Why is this so hard for you to understand? Are you not affected by your goals? And does this affection not cause passion within you? Do you have any understanding of the concept of "affection" at all? -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Unfortunately, we can't see "purpose" in the non-self world with our physical senses, but we can infer Intention from the behavior of people & animals that is similar to our own, as we search for food or other necessities, instead of waiting for it to fall into our mouths. Some of us even deduce Teleology in the behavior of our dynamic-but-inanimate world system, as described by scientific theories. If there is no direction to evolution, how did the hot, dense, pinpoint of potential postulated in Big Bang theory manage to mature into the orderly cosmos that our space-scopes reveal to the inquiring minds of the aggregated atoms we call astronomers. Ironically, some sentient-but-unperceptive observers look at that same vital universe, and see only aimless mindless matter moving by momentum.Regarding the significance of teleology and its place in Aristotle's metaphysics, I happened on a very succinct explanation in a video talk by cognitive scientist Lisa Feldman Barrett. She simply says that teleology is 'an explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose which they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise'. That says a lot in very few words, as it demonstrates the sense in which reason also encompasses purpose for Aristotle, in a way that it does not for modernity. — Wayfarer

The current Philosophy Now magazine has several letters on the topic of Time. One says : "If time is subjective, an observer is needed to make the distinction between past & future, and so to turn a probabilistic quantum phenomenon into a known result." Another responded to Tallis' comment that "the most successful organism is the non-conscious cyanobacteria" with : "Humanity's domination of the planet is so extensive that evolution must be redefined." The next letter notes : "from the outside, reality is matter, from the inside, it's mind".

Aristotle knew nothing of gargantuan galaxies full of whirling worlds, or indeterminate quantum probability, or progressive novelty-creating evolution, or brainless bacterial objectives, but he could "see" that his primitive pre-industrial world was purposeful. "Everything has a function or purpose and its essential nature is to grow and achieve its purpose." https://open.library.okstate.edu/introphilosophy/chapter/__unknown__/ :smile:

Teleonomy : a sign of Aristotle's Final Cause : the End or Purpose

This essay brings to mind Terrence Deacon’s Incomplete Nature, FWIW. On what we observe as teleonomy: “…unrealized future possibilities appear to be the organizers of antecedent processes that tend to bring them into existence,…

https://medium.com/@mmpassey/this-essay-brings-to-mind-terrence-deacons-incomplete-nature-fwiw-83a7e2a4b1a7 -

mcdoodle

1.1k"Everything has a function or purpose and its essential nature is to grow and achieve its purpose." — Gnomon

mcdoodle

1.1k"Everything has a function or purpose and its essential nature is to grow and achieve its purpose." — Gnomon

This is to conflate two different ideas in Aristotle. What's usually translated as 'function' is 'ergon', the special nature of what is named, e.g. a knife cuts, humans engage in soul-based rational consideration. This is different to 'telos' or 'end', the purpose of an activity. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Thanks. Yet I think Aristotle did associate both ideas in his discussion of Natural Purpose.This is to conflate two different ideas in Aristotle. What's usually translated as 'function' is 'ergon', the special nature of what is named, e.g. a knife cuts, humans engage in soul-based rational consideration. This is different to 'telos' or 'end', the purpose of an activity. — mcdoodle

The "everything has a purpose" quote combines several words & meanings into a definition of Teleology*1 : essential nature (phusis) + work (ergon) => ultimate aim (telos). However, the universal Purpose (telos) of Nature is not the local purpose (ergon) of any particular element.

Instead of postulating Intelligent Design*2 though, he used more abstract & impersonal terms like First Cause & Final Cause. The initial Cause can also be interpreted as "design intent", which produces Essential Nature, which is processed by the teleological work of Evolution, to eventually result in the ultimate Goal : the Final Cause. Hence, Teleology is the Intentional Logic inherent in progressive Evolution.

Of course, Ari probably had only a rudimentary notion of Natural Progression*3, but his First Cause could do the Darwinian Selection, and the Formal Causes (natural laws) would produce the physical novelty (mutations) in the Material Cause (elements) necessary to fabricate the intended Final Form of Nature-in-general. Ari didn't specify, and we moderns still don't know, what that ultimate state will be. But we can, like Aristotle, recognize the signs of Intention (Prohairesis) in the progression of Nature from hot-dot to comfortably-cool-Cosmos. Physics (machine) needs Meta-Physics (intention) in order to evolve from Big Bang to Poetry to Philosophy. :smile:

*1. télos, lit. "end, 'purpose', or 'goal'") is a term used by philosopher Aristotle to refer to the final cause of a natural organ or entity, or of human art.

*2. Did Aristotle believe in intelligent design?

Which means that Aristotle identified final causes with formal causes as far as living organisms are concerned. He rejected chance and randomness (as do modern biologists) but unlike Dembski did not invoke an intelligent designer in its place.

https://philosophynow.org/issues/32/Design_Yes_Intelligent_No

*3. Aristotle's Evolution :

The concept of evolution is as ancient as Greek writings, where philosophers speculated that all living things are related to one another, although remotely. The Greek philosopher Aristotle perceived a “ladder of life,” where simple organisms gradually change to more elaborate forms.

https://www.cliffsnotes.com/study-guides/biology/biology/principles-of-evolution/history-of-the-theory-of-evolution -

Wayfarer

26.2kThis is to conflate two different ideas in Aristotle. What's usually translated as 'function' is 'ergon', the special nature of what is named, e.g. a knife cuts, humans engage in soul-based rational consideration. This is different to 'telos' or 'end', the purpose of an activity. — mcdoodle

Wayfarer

26.2kThis is to conflate two different ideas in Aristotle. What's usually translated as 'function' is 'ergon', the special nature of what is named, e.g. a knife cuts, humans engage in soul-based rational consideration. This is different to 'telos' or 'end', the purpose of an activity. — mcdoodle

However, Aristotle's fourfold causality - formal, final, material and efficient - was assumed to be operative at the level of organisms and in the activities of human agents such as builders, was it not?

A Brief Excursion into the History of Ideas.

There's a succint description of telos in an IEP article on Aristotle's 'telos', from which:

The word telos means something like purpose, or goal, or final end. According to Aristotle, everything has a purpose or final end. If we want to understand what something is, it must be understood in terms of that end, which we can discover through careful study. It is perhaps easiest to understand what a telos is by looking first at objects created by human beings. Consider a knife. If you wanted to describe a knife, you would talk about its size, and its shape, and what it is made out of, among other things. But Aristotle believes that you would also, as part of your description, have to say that it is made to cut things. And when you did, you would be describing its telos. The knife’s purpose, or reason for existing, is to cut things. And Aristotle would say that unless you included that telos in your description, you wouldn’t really have described – or understood – the knife. This is true not only of things made by humans, but of plants and animals as well. If you were to fully describe an acorn, you would include in your description that it will become an oak tree in the natural course of things – so acorns too have a telos. Suppose you were to describe an animal, like a thoroughbred foal. You would talk about its size, say it has four legs and hair, and a tail. Eventually you would say that it is meant to run fast. This is the horse’s telos, or purpose. If nothing thwarts that purpose, the young horse will indeed become a fast runner.

Notice that 'everything' in the above discussion seems to include only things made by humans (artifacts) and plants and animals. The concept is extended to the inorganic realm, in Physics, Book II, particularly chapters 1-3 and 8. This is where Aristotle argues that natural processes and objects have intrinsic purposes. For example, he discusses how natural elements like earth, water, air, and fire have natural places to which they move. This is where the now-infamous claim is made that stones 'prefer' to be nearer the earth. Earth moves downward, while fire moves upward, each seeking its natural position in the cosmos. This movement towards their natural places is considered their telos.

This is the aspect of Aristotelian physics that was overturned (or demolished!) by Galileo and the scientific revolution. Galileo, through his experiments and observations, demonstrated that the motion of inanimate objects could be explained without reference to inherent purposes or final causes. For instance, he showed that objects fall at the same rate regardless of their composition (when air resistance is negligible) and that an object in motion remains in motion unless acted upon by an external force, laying the groundwork for Newton's first law of motion (inertia).

This shift marked the transition from a teleological view of nature, where purpose and final causes were central, to a mechanistic view, where natural phenomena are explained through efficient causes and mathematical laws. The mechanistic approach focuses on the material and efficient causes, emphasizing the interactions and forces that bring about motion and change without invoking intrinsic purposes. The broader context was the corresponding demolition of the Ptolmaic cosmology and the earth-centred universe, the collapse of the great 'medieval synthesis'.

But then the pendulum swung too far the other way. From everything being 'informed by purpose', modern science declared that nothing is. In the physicalist view, all biological processes, including those that seem goal-directed, are ultimately reducible to physical interactions and can be fully explained by the laws of physics and chemistry. From this standpoint, teleological language (such as "purpose" or "goal") is generally seen as a shorthand for describing complex processes that can, in principle, be fully understood in non-teleological terms, and specifically in mechanistic terms. Never mind that in reality, machines are only ever built by intelligent agents - Newton's deist god was sufficiently removed from the action to be practicallyimperceptibleinsignficant. It was only a matter of time until God became 'a ghost in his own machine', so to speak. (This is the subject of Karen Armstrong's excellent 2009 book A Case for God.)

Anyways, teleology proved indispensable for biology, so it made a comeback under the neologism teleonomy, the Wiki article on which (attached) is replete with hair-splitting distinctions between 'actual' and 'apparent' intentionality (which, notice, is also the keyword that kick-started the entire phenomenological tradition.)

As Etienne Gilson noted, philosophy always seems to live long enough to bury its undertakers. -

Johnnie

33Per se causes bring out the effect through themselves. Per accidens causes are merely conjoined with the per se cause. So the the wisdom of Aristotle does not directly cause him to be hungry. It can only be an accidental cause of his hunger insofar as it for example makes him use his brain more.

Johnnie

33Per se causes bring out the effect through themselves. Per accidens causes are merely conjoined with the per se cause. So the the wisdom of Aristotle does not directly cause him to be hungry. It can only be an accidental cause of his hunger insofar as it for example makes him use his brain more.

This is from Physics book 2:

That which is per se cause of the effect is determinate, but the incidental cause is indeterminable, for the possible attributes of an individual are innumerable.

I can make an argument that per se causes can't possibly be identical with the effect (I thought it's obvious but ok):

First of all, it's a title of a chapter in Physics VII: "It is necessary that whatever is moved, be moved by another." Another is not identical. Unless you say that Aristotle says that beside the immediate mover there is yer another cause of an effect which is identical with the effect.

Second Aristotle admits chains of per se causes. Multiple things can't be identical. The prime mover is a per se cause of all movement. Are you to suggest that the prime mover is identical to every movement? That would be ridiculous in Aristotle.

Also the amount of people with their own completely ignorant interpretation is saddening. It's not you, you make sense and the essential/simultaenous distinction is subtle and it's a wide problem in the litterature). The definition you quoted concerns Scotus, not all scholastics definitely. Aquinas and Suarez wouldn't agree. And they're taken to be the orthodox Aristotellians, Scotus' doctrines are controversially Aristotellian.

As to the non--simultaneity of immediate cause and effect - ok I just found a passage in Aquinas' commentary to Posterior Analytics touching just on this issue:

But although the motion has succession in its parts, it is nevertheless simultaneous with its movent cause. For the moveable object is moved at the same time that the mover acts, inasmuch as motion is nothing else than the act existing in the moveable object from the mover, such that in virtue of that act the mover is said to move and the object is said to be moved. Indeed, the requirement that the cause be simultaneous with what is caused must be fulfilled even more in things that are outside of motion whether we take something outside of motion to mean the terminus of the motion-as the illumination of air is simultaneous with the rising of the sun--or in the sense of something absolutely immovable, or in the sense of essential causes which are the cause of a thing’s being.

It seems you're right - an immediate mover must be simultaneous with the actualization. But it's not identical. Also there are per se causes which are not simultaneous with the effect. (consider a transformation of an element, an efficient cause ceases to be once the effect is in actuality). -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

Werner's observation is interesting.

I directed my comment more at the objections I have made over the years addressing Gerson's argument about "naturalism" as an antipode to the eidetic.

You have made much of the difference between ancient and modern ideas of the physical. How comparisons of that sort are made rely heavily upon what is understood by specific text that talks about that sort of thing.

Challenging Gerson's reading of the text is not equivalent to challenging what Gerson makes of it. Without that distinction, we could all be talking about anything we like. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBob had been affected by the window and had a passion to break it? — tim wood

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kBob had been affected by the window and had a passion to break it? — tim wood

The important aspect to recognize in understanding Aristotle's teleological metaphysics, is that the goal, end, or objective, is intermediary between the human being and the material world. The human being only affects the material world through the means of intentions, goals, ends or objectives, and likewise, material world only affects the human consciousness through the intermediary which is the person's intention.

The idea of an intermediary is derived from Plato who solved the interaction problem of idealism through the introduction of a third aspect "passion", which is the intermediary between the mind and body. The well disposed, tempered individual, has control over one's body, directing it toward the good, through the medium of passion. However, in the the ill-tempered individual the role of passion is reversed, such that the body influences the mind's goals and objectives in a bad way, through the means of passion. The latter is the case in your example, when Bob's mind is affected by his passion he desires to break the window, and this is an ill-tempered act.

The nature of the intermediary is what Aristotle addresses in that part of Posterior Analytics which Df referred to 94-95. In the case of final causation the role of the intermediary is reversed from that of efficient causation.

94b 22-25Incidentally, here the order of coming to be is the reverse of what it is in proof through efficient cause: in the efficient order the middle term must come to be first, whereas in the teleological order, the minor, C, must first take place, and the end in view comes last in time. -

Wayfarer

26.2kYou have made much of the difference between ancient and modern ideas of the physical. — Paine

Wayfarer

26.2kYou have made much of the difference between ancient and modern ideas of the physical. — Paine

I’m very interested in history of ideas. That is not as vague a term as it sounds, it is an actual academic discipline, usually associated with comparative religion departments. The book which is said to have given rise to that discipline is The Great Chain of Being by Arthur Lovejoy (1936 - turns out to be rather a turgid read, but anyway…) I’m pursuing the theme of how physicalism became the ascendant philosophy in Western culture and what the changes were in ways of understanding that gave rise to that. Platonism and how it developed is obviously central to that.

For example - Werner Heisenberg’s adaption of Aristotle’s ‘potentia’ (as noted above). As it happens, Heisenberg was a lifelong student of philosophy, he was known for carrying around a copy of the Timeaus in his University days. His Physics and Philosophy and some of his other later writings are very philosophically insightful in my opinion.

I don’t want to expound on the minutiae of divergences between Aristotle and Plotinus, for example, as I’m not equipped to do so, and, as I said, I’m considering the issues at a high level. And I will generally defer on any close readings of the text, to those who have familiarity with them, although I might take issue with matters of interpretation from time to time. -

Dfpolis

1.3k

Dfpolis

1.3k

Thank you for your comments.Per se causes bring out the effect through themselves. Per accidens causes are merely conjoined with the per se cause. So the the wisdom of Aristotle does not directly cause him to be hungry. It can only be an accidental cause of his hunger insofar as it for example makes him use his brain more. — Johnnie

I did not discuss this distinction, which I agree with. I discussed the difference between simultaneous and time-sequenced efficient causality, which are called "essential" and "accidental" causes in the Scholastic tradition.

"All causes, both proper and accidental, may be spoken of either as potential or as actual; e.g. the cause of a house being built is either a house-builder or a house-builder building." (Physics III, 3, 195b4f).

...

"The difference is this much, that causes which are actually at work and particular exist and cease to exist simultaneously with their effect, e.g. this healing person with this being-healed person and that

housebuilding [20] man with that being-built house; but this is not always true of potential causes—the house and the housebuilder do not pass away simultaneously." (Physics III, 3, 195b16-21)

Please ignore claims that I am identifying causes and effects. I am not. What is identical is the action of A actualizing the potential of B and the passion of B's potential being actualized by A. Clearly, a builder building is not a house being built. Still, they are inseparable because there is no builder building without something being built, and vice versa .First of all, it's a title of a chapter in Physics VII: "It is necessary that whatever is moved, be moved by another." Another is not identical. Unless you say that Aristotle says that beside the immediate mover there is yer another cause of an effect which is identical with the effect. — Johnnie

No, but as the ultimate source of actualization here and now, the Prime Mover is inseparable from (not identical with) potential being actualized here and now.Are you to suggest that the prime mover is identical to every movement? — Johnnie

Some of Aquinas's proofs for the existence of God (in the Summa Contra Gentiles and in the Summa Theologiae) assume and require essential causality to work.The definition you quoted concerns Scotus, not all scholastics definitely. Aquinas and Suarez wouldn't agree. And they're taken to be the orthodox Aristotellians, Scotus' doctrines are controversially Aristotellian. — Johnnie

It is now generally acknowledged that St. Thomas is as much Neoplatonist as Aristotelian. The commentary tradition he received distorted Aristotle in an attempt to reconcile him with Plato.

I have read one book on Scotus and claim no expertise. I quoted the article on Scotus because that is what I could find with Google, but I believe I first learned the distinction from a Thomist author I can't recall in an article about Aristotle's proof of a prime mover.

I am not sure what you are trying to illustrate.(consider a transformation of an element, an efficient cause ceases to be once the effect is in actuality). — Johnnie -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe window is broken by Bob absent any intention on his part - not that that makes any difference - an accident, Bob need not even be aware the window is broken. — tim wood

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe window is broken by Bob absent any intention on his part - not that that makes any difference - an accident, Bob need not even be aware the window is broken. — tim wood

Then this example is irrelevant to what we are discussing, the intentional activity of building. Also, the noun "passion" is related to this activity, only as the emotion of the one carrying out the activity. There is no coherent meaning for "the passion of being built".

But then the pendulum swung too far the other way. From everything being 'informed by purpose', modern science declared that nothing is. In the physicalist view, all biological processes, including those that seem goal-directed, are ultimately reducible to physical interactions and can be fully explained by the laws of physics and chemistry. — Wayfarer

Plato's "tripartite soul", as described in The Republic, allows for causation in both directions, mind ruling the body, and body influencing the mind. The intermediary between mind and body is commonly translated as spirit, or passion. By Plato's description, virtue occurs when the passion or spirit is allied with the mind, in ruling over the body. However, poor disposition allows that the spirit may ally with the body, to overwhelm the mind, when the person is overcome by emotion or sensation. So the well-tempered individual rules the body with the mind through the medium of spirit or passion, while the ill-tempered has a mind which is often overwhelmed by passion, thereby having one's mind improperly moved by the appetites and sensations of the body.

Plato extends this principle by analogy to the existence of the State. The State is healthy when the relations between the three classes. rulers, guardians, and working class, is ordered such that rulers rule with good philosophical principles. The guardians, in honour, are subordinate to the rulers, and the trades and activities of the workers are governed by the guardians. There is a principle associated with each of the three classes, rulers-intellectual, guardians-honour, workers-material goods. In the corruption of the State described by Plato, the honour of the guardians becomes tainted, and they turn toward the money of the class associated with material goods, rather than staying true to the intellectual principles of the ruling class.

How this relates to the difference between "the physicalist view", and the "informed by purpose" view, is the reversal of causation which the physicalist view has imposed on us. Ever since Newton's first law was established as the base for understanding cause and effect, the cause of change has been understood as necessarily external to the body which is changed. This principle, which sets the foundation for determinism, excludes the possibility of the source of change being internal to the human body, in the way that free will, intention, and final causation, was traditionally understood. The role of "purpose" is thereby excluded from this view.

The modern scientific view holds that causation is always sourced externally. The acts of human sensation are described as the external world having an effect on the body. the body then has an effect on the mind, in a chain of efficient cause. You can see how this perspective allows only for the existence of the ill-tempered soul (by Plato's principles). The virtuous, well-tempered soul is described by causation in the other direction, final cause, with the mind ruling the body, and causing it to do what is good, rather than being caused to do whatever the external world forces it to do through efficient causation.

Please ignore claims that I am identifying causes and effects. I am not. What is identical is the action of A actualizing the potential of B and the passion of B's potential being actualized by A. Clearly, a builder building is not a house being built. Still, they are inseparable because there is no builder building without something being built, and vice versa . — Dfpolis

You are ignoring the middle term, C. Aristotle uses a middle term, and if you include it, it becomes evident that you have reversed the representation to make final cause appear as efficient cause. The action of A is caused by the goal, C, the intended end, "a house". A is the means to the end. And, B, "the house being built", is nothing other than the end being actualized by the activity A.

In the particular instance in which a house is being built, the builder building is a house being built. The two are exactly the same. This is why we need the third term, "the house", which refers to the intended end of the activity. Otherwise you are simply insisting that the more general statement "a builder building" is different from the more specific "a house being built". But this is just a semantic difference which provides no information relative to causation. -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

We have both quoted 1066 in this discussion. Perhaps 1046 provides the most succinct expression of active and passive potentiality:

For one kind is a potentiality for being acted on, i.e. the principle in the very thing acted on, which makes it capable of being changed and acted on by another thing or by itself

regarded as other. — translated by Barnes

In such cases, the potentialities of both the 'agent' and the 'patient' need to be actualized together for change to happen. The unity of the moment described at 1066 does not cancel the different kinds of potential that come into being:

In a sense the potentiality of acting and of being acted on is one (for a thing may be capable either because it can be acted on or because something else can be acted on by it), but in a sense the potentialities are different. For the one is in the thing acted on; it is because it contains a certain motive principle, and because even the matter is a motive principle, that the thing acted on is acted on ... for that which is oily is inflammable, and that which yields in a particular way can be crushed; and similarly in all other cases. But the other potency is in the agent, e.g. heat and the art of building

are present, one in that which can produce heat and the other in the man who can build. — ibid. 1046a19

While the house as it being built, each change is necessary as relates to what can be changed:

Since that which is capable is capable of something and at some time in some way –with all the other qualifications which must be present in the definition–, ... as regards potentialities of … [those things that are non-rational; e.g. the fire] ... when the agent and the patient meet in the way appropriate to the potentiality in question, the one must act and the other be acted on ... For the non-rational potentialities are all productive of one effect each. — ibid. 1047b35

What is possible to be made is bounded by the potentiality of all the components involved. The art involved brings about necessary changes through a series of different processes (plus accidental changes such as bonehead decisions and weather). When the house is completed, the result is just as necessary and accidental as it was the day it started. Those components do not share the telos of the builder. They are only what they are for. The house as a whole has come into being. The changes can stop. -

Leontiskos

5.6kThat is an interesting question contrasting the ancient against the modern. I don't know how to think about Gerson's thesis in that context. My retort was to say that the "transjective"t sounded like a case of "having one's cake and eating it too" that Gerson objected to. A compromise between "materialists" and "idealist"; A position upon the history of philosophy as practiced now combined with an interpretation of ancient text. — Paine

Leontiskos

5.6kThat is an interesting question contrasting the ancient against the modern. I don't know how to think about Gerson's thesis in that context. My retort was to say that the "transjective"t sounded like a case of "having one's cake and eating it too" that Gerson objected to. A compromise between "materialists" and "idealist"; A position upon the history of philosophy as practiced now combined with an interpretation of ancient text. — Paine

That's possible, but I understand Wayfarer's implicit source (John Vervaeke) to be using "transjectivity" to uphold Platonism and oppose naturalism.

The difference between Plotinus and Aristotle that I have argued for is not put forward with that design. The ideas seem different to me. — Paine

Good posts. I agree with what you say about Aristotle in them. I would have to go back to see what you've said about Plotinus. -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

I am not familiar with Vervaeke. Can you hook me up with a bit of text where he presents this view of Platonism? -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

I agree with your reading that passion is a compliment of action. I also agree that Aristotle uses grammar to illustrate the condition.

But I also think Aristotle is trying to introduce some views of causality that are counter intuitive. What makes the 'crushable' crushable belongs to the being as something that could happen anytime when it is in close proximity with the active being. The being-acted-upon is made actual as a result of its given potential together with the other being's potential to act. This leads to Aristotle arguing for a view he expresses as reached as a matter of no recourse, perhaps even reluctantly.

But the cause of this is that the potentiality of which it is the activation is incomplete.1234 And because of this it is difficult to grasp what movement is, since it must be posited either as a lack or as a potentiality or as an activity that is unconditionally such. But evidently none of these is possible. And so the remaining option is that it must be what we said, both an activity and not an activity |1066a25| in the way stated, which, though difficult to visualize, can exist. — ibid. 1066a20

I read this passage as completing the journey began in Theta 3:

There are some people—for example, the Megarians—who say that a thing is capable of something only when actively doing it, and that when not actively doing it, it is not capable. For example, someone |1046b30| who is not building is not capable of building, but someone who is building is capable if and when he is building, and similarly in the other cases. But it is not difficult to see that the consequences of this are absurd. — ibid. 1046b28

Getting from dispensing with one view out of hand to replacing it with a better one turned out to be a lot of work.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum