Comments

-

Is indirect realism self undermining?

Imagine a photograph taken of a dancer. It's just a frozen pose and not the dance. We are the most intensely temporal creatures we are aware of. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Where in my body is my concept of open government. — RussellA

Look in the dimension of time.

Can you summarize that concept in a sentence ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?As regards claim two, partly true. Some things I see I do know its name. — RussellA

What is needed is claims, propositions, premises --- though classification will often lead in that direction. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?If my belief that it will rain tomorrow isn't in my mind, how can I know that this is my belief. — RussellA

Now that you mention it, I think beliefs would largely (maybe usually ) function inferentially in the usual way of folk psychology. A guy on LSD jumps off a building, because (we speculate) he believed he could fly --even without articulating that belief. But we articulate in our attempt to explain.

Note that we attribute beliefs to dogs and cats too.

If you claimed to believe P, people could still argue you were lying. You might fear that you are lying to yourself. Or you could be very confident, say it out loud, etc. So it's a rich issue. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?meaning that concepts only exist in the minds of the individuals making up the public body — RussellA

Concepts don't exist in the head. They exist in the movements of the body, including the movements of mouth and hand and all the [ other kinds of ] action that claims are used to justify, explain, predict.

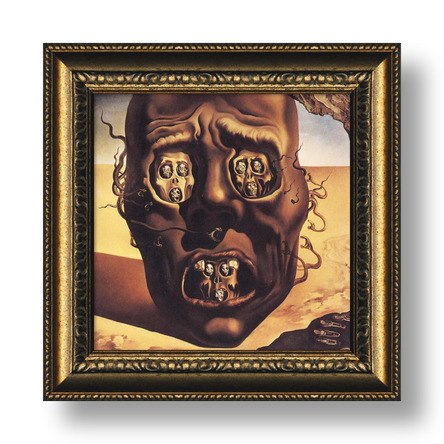

This is one of the problems with indirect realism. It's dualist ! You are trapped in your head. But I say we perform conceptuality, primarily in the time dimension, for we are the timebinding primate. What Hegel calls Geist ('spirit') is just complicated patterns in the Nature from which it emerged. What is called consciousness is, in my opinion, better understood as the being of the world for a [discursive] self. A 'conscious' person sees the world and not immaterial meanings and sensations, etc.

To me anyway that makes more sense, but I didn't start here. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Here's Brandom on Hegel:

Hegel denies the intelligibility of the idea of a set of determinate concepts (that is, the ground-level concepts we apply in empirical and practical judgment) that is ultimately adequate in the sense that by correctly applying those concepts one will never be led to commitments that are incompatible according to the contents of those concepts. This claim about the inprinciple instability of determinate concepts, the way in which they must collectively incorporate the forces that demand their alteration and further development, is the radically new form Hegel gives to the idea of the conceptual inexhaustibility of sensuous immediacy. Not only is there no fore-ordained “end of history” as far as ordinary concept-application in our cognitive and practical deliberations is concerned, the very idea that such a thing makes sense is for Hegel a relic of thinking according to metacategories of Verstand rather than of Vernunft.

All that he thinks the system of logical concepts he has uncovered and expounded does for us is let us continue to do out in the open, in the full light of self-conscious explicitness that lets us say what we are doing, what we have been doing all along without being able to say what was implicit in those doings. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

Some hold that idiolects in this sense do not exist or that the notion is useless or incoherent, but are nonetheless happy to use the word “idiolect” to describe a person’s partial grasp of, or their pattern of deviance from, a language that is irreducibly social in nature.

I'm happy with the bold part. In fact that's probably all of us as individuals. But we push toward a center. The philosopher as such manifests a truthbringing intention. I'm not sure that's the best way to put it, but there's a motive, a push, a project. It is deeply social, essentially outward and self-transcending.

Just as a coherent self is an infinite task, so is the community's co-articulation of the world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

I think it's cool that you looked into Brandom. I've put a fair amount of time into his work, but of course I've only used a few key concepts of his, for my own purposes. I don't feel constrained by my influences, naturally.

such beetles are necessary, but lie beyond the aperspectival limitations of social norms and communication. — sime

To me private concepts is an oxymoron, but I'm open to something like a continuum. Philosophers try impose upon current norms, usually by appealing to norms which are not currently being challenged. They want an eccentric candidate inference or world-disclosing metaphor to become widely recognized. If one thinks concepts get their meanings from claims, then concept modification will often involve using familiar concepts in new inferences, thereby mutating the concepts. We also have an expressive enough language to talk about concepts directly, and such claims might be accepted as explication (obvious upon hearing, etc.)

I personally avoid talking about 'pure' or 'internal' meaningstuff which is contained in expressions. I suggest that equivalence classes of expressions are a nice alternative to the idea of this meaningstuff. Different sentences can be used for pretty much the same purpose, so they have the same meaning (as use). Eccentric uses are advertised and defended by philosophers for admission as standard uses. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?If a belief can be justified only on the basis of another belief, and beliefs only exist in the mind, then there can be no connection of any kind between the mind and the world. This is more an argument for Idealism than Realism. — RussellA

You are forgetting uncontroversial or undisputed basic statements. We might all believe the same witness, and reason from her testimony, to justify some more complicated claim.

Personally I wouldn't put beliefs 'in the mind.' Language is worldly. It is marks and noises of a certain kind.

When I see the colour red, I don't believe that I see the colour red, I know without doubt that I see the colour red. I don't need to justify my belief as it is not a belief in the first place.

IE, the Indirect Realist doesn't need to justify what they perceive through their senses. — RussellA

Do you see claims through your sense organs ? I think not. You don't bother to justify claims to yourself unless you feel doubt. Others may or may not expect justification. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?This is another quote from that paper. Since Rorty was Brandom's advisor, we seem to be getting a younger version of inferentialism here. Note that concepts rather than claims are the focus. This was eventually fixed --- and needed to be --- because claims and not concepts function as premises and conclusions.

https://philpapers.org/archive/KOORLT.pdf

Rorty’s argument was that the Quine-Sellars combine poses an enormous problem for a representationalist empiricism which makes use of two claims that seem unproblematic but turn out to be enormously puzzling once submitted to scrutiny: the first claim being that simple ideas come into the mind in the form of nonpropositional awarenesses, the second claim being that these ideas once in

the mind somehow get converted into something that can stand in inferential relations to propositions in the mind. Lockean ideas had always tried to play the double role of representations of an outside world and justifications for other inner ideas. But explaining how ideas can in fact do this double work is a task that may be impossible. Even the most obvious counterexamples stemming from cultural variance, perceptual illusion, and even just plain ignorance are enormously difficult to explain away. The rain outside may cause me to believe that the Gods are conspiring against me, but that belief is not therefore justified, especially if my audience for justification in this case is a group of evidence obsessed meteorologists, or perhaps neurosis-analyzing psychiatrists). Sellars helps Rorty show that nothing except a conceptually-structured belief can count as a justification for another belief (thus the physical fact of rain by itself justifies nothing) – only concepts are capable of being justifiers. Quine helps Rorty show that our being caused to believe something does not for that reason alone justify that belief (thus the rain causing me to further faith the conspiracy by itself justifies nothing) – no concept by itself can be an unimpeachable justifier. Thus taken together, as Rorty showed us to take them, Sellars and Quine break the link between causation and justification at the heart of modern epistemology. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Then how can there be a public language about apples and the colour red if our private experiences of apples and the colour red are different. — RussellA

Concepts are public. Concepts are norms. How else could you even ask me that question with a sense of being entitled to an answer ? A tacit commitment to the philosophical situation is prior to every other issue. I touch on that in my new thread, if you want to join.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/14264/nothing-is-hidden -

Nothing is hiddenAren’t you putting the norms before the generating process that creates and continually modifies those norms? — Joshs

Time is one's [ the Anyone's ] self-confrontation. A generation is a bundle of adversarially cooperative persons -- a parallel but competitive computation/articulation of the real ?

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/229403462.pdf

Geist refers to the normative in general. As such reference to the spiritual is a reference to the normative; correspondingly talk of normativity is talk of Hegelian Spirit... In this view, Geist arises with intersubjectivity; Geist has intersubjectivity as its ground and could not exist outside of it.

I think spirit's norms have nature as their foundation and origin -- that they are modifications of nature, a timebinding dance of nature's legs.

always from a vantage that subtly reinvents the basis of the norm. A space of reasons is always particularized on the basis of each of its participants As to the questions of what is at stake and at issue, the ‘norm’ can’t answer these, becauseit is precisely the sense of space of reasons that is under question from the vantage of each participant and in each new context of use. That is why the contexts of norms are always only partially shared. — Joshs

I agree. Philosophy is something like outsiders pushing toward the inside, into the center. It's a will to establish claims, to be taken as authoritative, to be recognized, to install tomorrow's norms. It ought to be the bringing of a gift ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Here are some good points against indirect realism, IMO.

https://philpapers.org/archive/KOORLT.pdf

By giving a causal account of how ideas get formed in the mind as the result of the external world

pouring into us through the senses we can arrive at an epistemological account of how these ideas can be put together in knowledge. Causation here yields justification, or in Rorty’s description, “a quasi-mechanical account of the way in which our immaterial tablets are dented by the material world will help us know what we are entitled to believe” (1979, 143). The history of seventeenth century philosophy forwarded in Mirror has it that the legacy of modern philosophy is a Cartesian-Lockean metaphor in which minds are construed as representing machines whose units of representation are ideas.

...

What Sellars’s “Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind” helped Rorty to show was that a belief can be shown to be justified (or unjustified) only on the basis of another belief or set of beliefs. A belief cannot be shown to be justified (or not) on the basis of what Sellars mocked in his essay as “the unmoved movers of empirical knowledge” (Sellars 1956, 77). This led Sellars to the point that there is no way to draw a direct link between the supposedly immediate (or non-conceptual) givens of perception and the mediated (or conceptualized) takings of knowledge. For perceptual inputs (e.g., sensations) to be in any way relevant to processes of justification and hence of knowledge they must already be conceptual in form so as to occupy some place in what Sellars called “the logical space of reasons” (1956, 76). Sellars’s claim, upon inspection, is a rather modest one: every conclusion in belief stands in need of

reasons as supporting premises. Modesty, of course, is often a high virtue in philosophy. And in any event, its appearance can be deceptive. In this case, a modest point calls into question the very project of epistemological foundationalism. For what Sellars is suggesting is that as-yet-unconceptualized

perceptual inputs cannot play a determinative role in justificatory practices involving classificatory concepts. The Jamesian “blooming buzzing confusion” of raw sensation may find its way into our experience on occasion but it cannot play any direct justificatory role in so doing.

...

Perceptions are of course conceptually classifiable but not for that reason justifiers of any particular conceptual classification. Every perceptual given is always amenable to a multiplicity of conceptual takings – this is Quine’s thesis of ontological relativity or inscrutability of reference, made memorable in his example of the ‘Gavagai-Rabbit’ translation (Quine 1960, §7ff.). It follows that concepts by themselves do not yield justifications. Concepts are not, merely in virtue of being concepts, justifiers for any other concepts, even though (as Sellars showed) only a conceptually-laden belief can justify a conceptuallyladen belief. Quine’s claim also seems rather modest. But the view it leads to is the radical divorce of epistemology and ontology which follows from the insight that, as Rorty put it, “there is no such thing as direct acquaintance with sensedata or meanings which would give inviolability to reports by virtue of their correspondence to reality, apart from their role in the general scheme of belief”

(1979, 202). Rorty takes Quine to show that perceptions do not enter into us one at a time, but rather as part of complex webs of theory and practice such that any perception is always bundled together with many other perceptions as well as many other beliefs. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

OK, that was quite helpful.

I guess the delicate issue is whether the current scientific image (or any possible scientific image) makes sense as the Real which causes experiences of red apples. To me that 'image' would (in this context) just be more appearance, albeit organized conceptually in an impressive way.

I used to agree more with Kant, so I can relate. It's a tricky issue in any case. -

Nothing is hiddenWhat is the intention of the philosopher ? To impose a claim, establish as a premise for further use, stack one more brick on the tower. Is there a feeling of rightness ? One feels, in the light of norms taken to be given and authoritative, that a next step is justified. As Feuerbach might put it, it's like participating in a distributed computation, finding a consequence or disclosing metaphor, and reporting back to the blockchain.

-

Is indirect realism self undermining?If all Direct Realists are immediately and directly seeing the same world, on what grounds can they disagree about what they see. — RussellA

Different positions in space, different sense organs, different personalities. The 'directness' is the absence of intermediaries and not (and never was) the assumption of an identical response ('experience'). Two people can see the same apple differently. Joe is nearsighted. Jane is colorblind. They don't see individual images of the apple directly. They both see the apple directly, but differently. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

:up:It does not follow from the fact that different people have different accounts of what happened that they did not all watch the same set of events unfolding in real time. — creativesoul

Yes, and we can see it the grammar of the words. It's a different account of the same events. All of the accounts intend the same 'object.' But I'm just making conceptual norms explicit in saying so. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?It is through these respective worldviews that people 'see' the world. — creativesoul

:up:

Yes. We might use the metaphor of a distorting lens. I might claim that you are biased, and you might claim that I am. But we look at apples, not at images of apples. We intend and talk about apples, not images of apples. (Of course we can talk about images of apples as philosophers debating indirect versus direst realism.) -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

Correct me if I am wrong about your view :

Apples aren't red, because redness is in the brain.

============================================

But why do you believe in the apple in the first place ?

Why should you believe that shapes exist outside of the brain ?

Why believe in 3D space at all ?

Why believe that elementary particles (strings, etc.), mere ideas of the imagination, are not only outside the brain but 'under' all appearance as their truth and reality ?

If everything is image (mediated), it's all 'really' in the brain. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?If we have an indirect access to whatever that is that is not consciousness, then it seems we have a direct access to consciousness by comparison. In this set up consciousness is a real illusion which is indirectly related to whatever it is that is outside of consciousness, while consciousness itself is direct. — Moliere

:up:

This is the dualism I've been mentioning. The given is the image of the hidden.

But I say it's all on the same inferential plane, has to be to make sense. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I don't think that in reality you are a Direct Realist, but someone who has the position that the world exists fundamentally in language. — RussellA

The world is much more than language, yes, but I have to use language to reason about it --- and language discloses / articulates / shapes the world in certain ways. I walk into a men's restroom, not just some room. We largely live in our symbols.

My question to the Direct Realist is, if all observers are directly observing the same facts in the external world, then why do different observers make different judgements about the moment when one fact changes into a different fact. — RussellA

People can disagree about the world and be wrong about the world, but they are seeing and talking about the world and not their images of it.

Now one can invent a weird language of internal images, and physicists have talked of phlogiston and ether (both eventually abandoned as useless), so it's not a matter of wrong or right but of better or worse. -

Nothing is hiddenWould you say your view of rationalism is compatible with Donna Haraway’s? — Joshs

Haraway sounds reasonable in the quote, but my focus in more narrow. I am trying to articulate the relatively stable 'given' of philosophy. What does every philosopher as such at least tacitly presuppose ? I am unfolding the concept of philosopher, largely inspired by Heidegger, but with an inferentialist twist from Brandom.

Our situation is being-in-our-world-in-our-language-together, where language includes the logic thereof in terms of semantic and inferential norms. It's rationalism because I think doing philosophy always already assumes this situation, if only tacitly.

There are, according to the rationalists, certain rational principles—especially in logic and mathematics, and even in ethics and metaphysics—that are so fundamental that to deny them is to fall into contradiction. The rationalists’ confidence in reason and proof tends, therefore, to detract from their respect for other ways of knowing.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/rationalism

'Experience' enters the system in terms of statements which are accepted without being the conclusions of inferences. We can read off measurements from a machine or just sufficiently trust a witness. -

Nothing is hidden

Nice quote !It is only when immanence is no longer immanence to anything other than itself that we can speak of a plane of immanence. ~Deleuze — 180 Proof

I haven't seriously looked into Deleuze yet, but it sounds like what I'm also trying to get at.

All entities are linked (are meaningful!) inferentially ('structurally') , so they are on the same plane. -

Nothing is hidden

"A Social Route from Reasoning to Representing"

https://sites.pitt.edu/~rbrandom/Texts/A%20Social%20Route%20from%20Reasoning%20to%20Representin -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

I relate to the sense I think we all have of being behind our eyes. I also think awareness requires a functioning brain. But the redness of that distant apple is just as intuitive.

You call that experience of distant redness an illusion. What is this illusion ? How can the illusion, trapped in the brain, be of something red at a distance ? And why would shape not also be an illusion ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I can't see what "social norms governing inferences" amounts to — sime

Because you don't understand social norms governing inferences, I'm going to write a poem now about Frosty the Snowman (with help from Google's Bard.)

Frosty the Snowman,

Could dance and he could sing,

And he loved to play,

In the winter snow,

With all the children of the town.

Frosty the Snowman,

Was a friend to all,

And he brought joy,

To everyone he met,

Until the day he melted away.

Given that society rarely agrees upon anything — sime

Given !

Underestimate norms granted for take don't or semantic. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

Even if that redness is causally connected to the brain, I don't see why you need to put it in the brain. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?create the illusion — Michael

What is an illusion ? And why isn't it real ? Why does the redness that sure seems to stick on the apple not 'really' there ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?By convention sweet and by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention colour; in reality atoms and void. [Democritus, c. 460-370 BCE, quoted by Sextus Empiricus in Barnes, 1987, pp. 252-253.]

By convention also : atoms and void ! Fascinating this willingness to treat shape as real and so much else as not real...geometric-platonistic bias ? Why not the nose for the one true access to the Real ? Ah because we need eternal objects...and smells won't stay put. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

Why is conscious experience not real ? If it's (as you say ) made of strings/atoms, etc. ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?This is the illusion of conscious experience. It seems as if it extends beyond the body, which is physically impossible. — Michael

There's something iffy here. What is this illusion of conscious experience ? Are we back to dualism ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?My point from the start has only been that words like "red", "sweet", and "pain" refer to some characteristic of conscious experience, not to some property of the apple or fire. — Michael

I would still say that the apple is red. The point of 'nothing is hidden' (for me) is a rejection that everyday reality is a kind of appearance or paintjob on some Real that hides beneath.

I understand that we tend to explain something like the perception of redness in terms of the brain. That's fine. But the concept red tends to be applied to the objects. Since concepts are norms, I'd just appeal to how we tend to use the concept. -

Nothing is hiddenIn case anyone finds this helpful ( obviously I think this dude is brilliant).

https://sites.pitt.edu/~rbrandom/Texts%20Mark%201%20p.html

One of [ Kant's ] cardinal innovations is the claim that the fundamental unit of awareness or cognition, the minimum graspable, is the judgment. Judgments are fundamental, since they are the minimal unit one can take responsibility for on the cognitive side, just as actions are the corresponding unit of responsibility on the practical side... The “emptiest of all representations”, the “’I think’ that can accompany all representations” expresses the formal dimension of responsibility for judgments. Thus concepts can only be understood as abstractions, in terms of the role they play in judging. A concept just is a predicate of a possible judgment, which is why

The only use which the understanding can make of concepts is to form judgments by them.

For Kant, any discussion of content must start with the contents of judgments, since anything else only has content insofar as it contributes to the contents of judgments.

...

On the side of propositionally contentful intentional states, paradigmatically belief, the essential inferential articulation of the propositional is manifested in the form of intentional interpretation or explanation. Making behavior intelligible according to this model is taking the individual to act for reasons. This is what lies behind Dennett's slogan: "Rationality is the mother of intention". The role of belief in imputed pieces of practical reasoning, leading from beliefs and desires to the formation of intentions, is essential to intentional explanation—and so is reasoning in which both premise and conclusion have the form of believables. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The key thing is that internal entities exist, and our words refer to them. When the person with synesthesia talks about numbers have colours, he's referring to some characteristic of his conscious experience, i.e. his neurological response to certain stimulation. He's not referring to some object out in the world that you or I can pick up. — Michael

I don't see a problem with reference, but the reference is not the meaning. The concept is not some conventional tag on a physical or psychological entity.

To refer to an entity is commit oneself in a certain way. If I say that X is a round, I ought not say that X is a square. I should not contradict myself.

But an object is the kind of thing that can't contradict itself ( squareness excludes roundness ). -

Is indirect realism self undermining?So do you agree that social norms are generally a terrible way of inferring anything about an individual's behaviour? — sime

I radically disagree.

Social norms govern inferences in the first place. The situation is liquid enough, however, that an individual philosopher can get a new inference accepted / treated as valid. --- typically by using inferences which are already so treated along with uncontroversial premises. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?

I view philosophers as imposing themselves on their community's rational norms --necessarily in terms of those norms. Following Brandom, I focus on which inferences are treated as valid. I then look for the meaning of concepts within the inferential relationships of claims involving those concepts.

Ethics is first philosophy.

Claims, not concepts, are semantic 'atoms.'

To make a claim is to make a commitment. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Synesthesia is the perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway, e.g. seeing colours when sound stimulates the ears. — Michael

Yes. The key thing is that concepts of internal entities are still public norms. If Suzy claims to have synesthesia, then, all other things being equal, we'd expect her to be able to give an example.

Claims commit claimants to the implications of their claims. Selves are expected to avoid contradictions in the set of claims for which they are currently responsible. We can get lots of milage from this, I think. -

Nothing is hidden1

The world is all that is the case.

1.1

The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11

The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts.

1.12

For the totality of facts determines what is the case, and also whatever is not the case.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus

Why of facts and not of things ? Whatever W's intention, I read this as brilliant avoidance of a confusing break between sense and some senseless stuff to which sense is supposed to somehow refer. One can say everything is made of atoms. The world includes that fact (if it happens to be a fact). But the world itself is not atoms.

The world is not a thing, not an entity. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The person with synesthesia does describe numbers as having colours. — Michael

I think we can include an entity like synesthesia, but its meaning will be the role it plays in claims in inferences.

plaque flag

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum