Comments

-

Metaphysics DefinedMy point was not that we wouldn't share commonalities with other beings. My point is that how the world is perceived and understood depends not just on the characteristics of the thing being perceived but also on the characteristics of the perceiver.

— Andrew M

I'd say that how the world is perceived and understood depends entirely on the perceiver/understander. — tim wood

I'm not sure I understand you. Suppose Alice sees a bird fly by and land on a branch. She perceived the bird flying and then perceived it landing. The difference in those two cases is with the thing perceived (the bird) not the perceiver (Alice).

So that is an example where how the world is perceived and understood depends at least in part on the thing being perceived. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsIn ordinary use, there is an isomorphism between statements and the world, as captured by formulations such as "p" is true iff p. On that schema, we are mistaken when our statements don't reflect the way the world is.

— Andrew M

Do you mean you think that the T-schema actually exhibits or requires an isomorphism between the sentence p (or its quotation or both) and the situation affirmed? Or was this only, like "reflect", a figure of speech?

If the former, we can get down to brass tacks. — bongo fury

The isomorphism (i.e., equal form) is between the state of affairs and the statement, as abstracted from their concrete instances. For example, it is raining outside (the state of affairs) and Alice says that it is raining outside (the statement).

So I'm curious what it means, on your view, for a statement to be true.

— Andrew M

Unless you just mean, how do I generally get or assess my information (science, ideally), I don't see how you are expecting that not to sound metaphysical. — bongo fury

I'm asking how you use the term "true".

For example, I assume you believe there were dinosaurs roaming the Earth millions of years ago based on evidence such as the fossil record. Is your belief true because you have formed it based on that evidence?

Or is it possible, in principle, for your belief to be false? Suppose, unbeknownst to us all, the fossils happen to be fakes planted long ago by aliens for their nefarious purposes. On conventional use, your belief is true if and only if there were dinosaurs roaming the Earth millions of years ago. -

Metaphysics DefinedThe realist argument is that we perceive and understand the world as human beings. There is no view from nowhere.

— Andrew M

"

Thomas Nagel’s primary aim in his book The View from Nowhere is to explore the various philosophical puzzles that arise from the tension between the subjective and objective standpoint. The subjective standpoint is the personal perspective of an individual person; it is her view of the world “from the inside,” the world as she sees it; it is her own private window on the world, so to speak. The objective standpoint is the impersonal perspective a person adopts when she conceives of the world “from the outside,” not as it appears to her but as it really is. From the subjective standpoint, a person is at the center of her world; from the objective standpoint, she is simply one of many people who all see the world as she does. Thus, Nagel also characterizes the objective standpoint as “centerless”; someone who looks at the world objectively strives to take in “the view from nowhere.”

Nagel is convinced that the tension between the subjective and the objective standpoints surfaces in many of the enduring questions of philosophy.

"

I agree with him. That's what I was referrring to. Many of the arguments in this and other threads are based on the conviction that science delivers just such a view. — Wayfarer

I know. That conviction is wrong. :-)

Science is simply a natural extension of everyday experience.

If a subject/object framing leads to tension and philosophical puzzles (as it does do), then maybe it's the framing itself that is the problem. Compare with the tensions and philosophical puzzles that Cartesian Dualism gave rise to in the past. -

Metaphysics DefinedThe realist argument is that we perceive and understand the world as human beings. There is no view from nowhere.

— Andrew M

Given the attempted granularity of the discussion, I'd call this facile. It implies, for example, that all the means and methods for understanding natural science are founded/grounded in the being of human beings. Hmm. I guess when the aliens finally come to rescue us from our follies that we'll have nothing in common with them - yes?

Edit: Even jackasses like beer. — tim wood

My point was not that we wouldn't share commonalities with other beings. My point is that how the world is perceived and understood depends not just on the characteristics of the thing being perceived but also on the characteristics of the perceiver.

A familiar example that highlights this is color perception in animals.

The lesson is that whether we can generalize our claims (or not) is always an empirical question, since the perceiver is part of the context.

Carlo Rovelli makes a related point regarding mathematics:

If there is a ‘platonic world’ M of mathematical facts, what does M contain precisely? I observe that if M is too large, it is uninteresting, because the value is in the selection, not in the totality; if it is smaller and interesting, it is not independent of us. Both alternatives challenge mathematical platonism. I suggest that the universality of our mathematics may be a prejudice hiding its contingency, and illustrate contingent aspects of classical geometry, arithmetic and linear algebra. — Michelangelo's Stone: an Argument against Platonism in Mathematics - Carlo Rovelli -

Metaphysics DefinedIt's important to understand what Schopenhauer means by his 'vorstellung' (usually represented as 'representation'.) He's not saying, like Locke was saying, that ideas represent objects. Nothing like that. It's closer to saying that the whole cognitive act, our whole act of knowing, and what we take as the external world, is really a creation of the mind - and that this is what constitutes knowledge (see the first paragraph).

But that *doesn't* say that 'the world is all in your mind'. That perspective comes from thinking you can stand outside of this whole process. But you can't stand outside it, as we are that process of knowing. I know it's a very contentious claim and a difficult argument. — Wayfarer

The realist argument is that we perceive and understand the world as human beings. There is no view from nowhere. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsYou keep going cosmic.

When we point symbols at things we sort them, and present them a certain way. The way they are is how they are sorted. We use experiment and such like to decide the best choices of pointing.

Platonism says (after a process of cosmic reasoning) that our pointing must also reflect the way the things really are, and introduces more things (properties, similarities etc.) to create a new level of sorting. To correspond with the first. — bongo fury

In addition to the natural world, Platonism posits a separate and prior world of the Forms. So, yes, the natural world is then a shadow or reflection of that Ideal world. There are two levels of worlds, so-to-speak. But Nominalism, in rejecting that, says that the natural world just is one's ideas (or the relevant consensus opinion) about it. As illustrated by your comment in bold above.

But in ordinary and scientific usage (which assumes neither Platonism nor Nominalism), the natural world is separate and prior to our ideas about it. By conceptualizing it in that way, it is possible for our ideas about the natural world to be correct or mistaken in a way that isn't merely a function of consensus opinion at the time.

Which brings in the idea of truth. In ordinary use, there is an isomorphism between statements and the world, as captured by formulations such as "p" is true iff p. On that schema, we are mistaken when our statements don't reflect the way the world is.

So I'm curious what it means, on your view, for a statement to be true. Does it simply mean that you classify the statement as true (according to some specifiable criteria), and thus it is something that you can't be mistaken about (as long as it did meet that specifiable criteria)? -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsAnd while a re-presentation always depends on a prior presentation (i.e., the world precedes language),

— Andrew M

Do you mean, when we point symbols at things, it depends on the things being there (not necessarily there and then) to be pointed at? Or something more elaborate, like the choice of symbols depending on the choice of things? — bongo fury

The first. There needs to be something that we are talking about beyond the talk itself. At least, there does if we want our talk to be useful or meaningful.

As I read you, it seems that it is the talk itself that constitutes the world. You define 'planet', 'orbit', 'Sun', etc., logically prior to which there were no planets orbiting the Sun. As if the symbols bring those things into being.

Oh, ok. I thought the contrast quite noticeable. But of course as a nominalist I'm used to interpreting similarity talk in that way. I don't know about the typical reader. — bongo fury

Presumably because you make some sort of (metaphysical?) distinction between those two claims ("The planets Mars and Venus both orbit the Sun" and "They are similar in that respect").

So, its following by (some kind of) implication from the earlier claim about the orbits is incidental, and you would perhaps rather have claimed the similarity as a bald fact? Like a physical property, perhaps? And not as being in a particular respect? — bongo fury

As the word "similar" is normally used, if two things have the same characteristic (as in this case, that the planets Mars and Venus both orbit the Sun) then those two things are similar in that respect. I don't see that as a "bald fact", more a straightforward implication based on conventional language use.

Like a physical property, perhaps? — bongo fury

No, I don't think a physical/non-physical distinction is useful here.

And not as being in a particular respect? — bongo fury

As mentioned earlier, claims are made by people. So "in a particular respect" is implicit in any claim, i.e., a claim entails a human perspective. From Lexico: "perspective 2. A particular attitude toward or way of regarding something; a point of view." So that also applies to claims about planets orbiting the Sun. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysics"from outside":

You keep saying it's nonsense (and metaphysics) to say that "how the world is" is dependent on how we describe it. I keep saying it's nonsense (and metaphysics) to deny it. — bongo fury

Yes, I agree that that is what we both say. :chin:

You ask me to use language to represent a state of the whole world without language. I have to remind you that is impossible, and the best we can do in that direction is represent a state of a part of the world and assume that it is represented from outside of it.

"as meta":

On that basis, we might say plenty of things in an object language; but saying things is just hot air, and we will inevitably desire to say things about how the hot air relates to things in the specified part of the world. "F = ma" won't be enough, and we will want to say how the symbols map onto things. I mentioned that I was excluding "similar" from the likely vocabulary of an object language. — bongo fury

OK, perhaps our disconnect is that I'm just making natural language claims. I'm not making claims about meta- and object-languages, nor of being "outside" the world (or "outside" part of the world).

Put simply, we are all a part of the world that we are making claims about, whether they are everyday claims or scientifically-informed claims. There is no "outside". That's the Neurath's Boat aspect. And while a re-presentation always depends on a prior presentation (i.e., the world precedes language), those representations themselves become an aspect of the world that can be re-presented (i.e., we can also talk about language, or art, as a subject in its own right). Maybe the examples below will clarify this.

The planets Mars and Venus both orbit the Sun.

— Andrew M

Sounds like science. Plausible as talk in an object language. — bongo fury

I'm just making a natural language claim. Of course I make this claim thanks to scientific discoveries. But it's nonetheless a claim about the way the world is, no different than claiming that the cat is on the mat (if it is).

They are similar in that respect.

— Andrew M

Quite a contrast: we're chatting about perspectives and descriptions. — bongo fury

There's no contrast. I'm just making a further natural language claim which, in this case, makes explicit what is implicit in the earlier claim. I'm not talking about perspective and descriptions. I'm describing (a part of) the world from my perspective. Which is also what I was doing with the earlier claim about orbits. Again this is just a natural language convention. Claims are made by people. There is no escaping one's perspective to make a claim from the "outside".

They were also similar in that respect billions of years ago

— Andrew M

Mixing the two: sneaky! But realistic. I'm not suggesting object- and meta-language are ever perfectly separated, outside of semantic theory. — bongo fury

So I'm again just making a natural language claim.

Now it seems that you think that is false.

— Andrew M

Only in the same way that the similarity is false of the planets now: i.e. in any sense supposed independent of language. — bongo fury

Hopefully my responses above make my position clearer. -

Gettier Problem ContradictionIt occurred to me just now that a simplified definition along these lines might be that a justification has to be a valid argument that is more likely sound than not. — A Raybould

Yes. And if the argument is sound, then the person has knowledge. Obviously there is no guarantee of that since the conclusion or a premise could be false (unbeknownst to them). But that's the trade-off that has to be made for claims to be justifiable at all, and therefore for knowledge to be possible.

On the other hand, having a quantitative concept of justification seems to fit with the jury instruction to return guilty if the premise that the defendant committed the crime is true 'beyond reasonable doubt', and also with the phrase that 'extraordinary claims require extrordinary evidence'. — A Raybould

Yes, in some contexts the standard for justification is higher.

Here we have the disjunction of two propositions, neither of which are part of Smith's knowledge, so it seems reasonable to say that their disjunction is not known by Smith, either. — A Raybould

Works for me. -

Gettier Problem Contradiction:up: Good comments! The conditional approach seems reasonable to me.

-

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsI have a rockery, with no language inside it. — bongo fury

Good to start with a point of agreement! :-)

I'm happy to say that any similarity between any two parts of it is relative to the language used (from outside) to label the parts. I recognise the notion (of similarity) as meta to any physical or mechanical concepts. Maybe that is a sticking point, I don't know. Perhaps if we clarify the example we may find out. — bongo fury

Perhaps you could unpack what the phrases "from outside" and "as meta" are contributing in your above explanation.

Let's also consider one more example. The planets Mars and Venus both orbit the Sun. They are similar in that respect. They were also similar in that respect billions of years ago well before any life on Earth emerged to notice that similarity and develop language to describe it.

Now it seems that you think that is false. Or at least somehow depends on answers to questions about gardens. This seems to be the sticking point. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsWasn't the world prior to the emergence of life a world without language?

— Andrew M

Depends... Is my garden a world without language? And calling a part of it a tree is correct because it is, independent of language? — bongo fury

The answer doesn't depend on those questions. On conventional use, there was no language prior to the emergence of life.

So implicit conventions are a matter of fact? Or do you mean that no one reasonably could, considering your argument, persist in the opinion that a theory was speaking "the language of the universe"?

Not that I'm one of those; my point was that both positions are metaphysical (although possibly redeemable in terms of object- and meta-language), and usually dispensible. — bongo fury

Conventions, like road rules, could be different from what they are. A person doesn't have to follow conventions, but the question might arise as to whether they are saying something useful or merely confusing themselves and others.

Any theory that describes the universe is going to depend on human language. There's no implication that the universe itself would depend on human language.

But "how the world is, independent of our agreement", though a laudable consideration in some contexts, is metaphysical claptrap in most. Science is on Neurath's boat, remaking it from earlier versions of itself, not from something meta. — bongo fury

Neurath's boat works fine as a metaphor for how we investigate the world from within it, and how language evolves as we learn more. Again there's nothing there that implies that the world being investigated depends on our language (or our agreement) about it. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsBut clearly something has gone wrong, as the things that a language (or other symbol system) likens to one another clearly don't have to be contemporaneous with it. So of course we can agree on that. But it doesn't get us any nearer to the chimerical "world without language". — bongo fury

Wasn't the world prior to the emergence of life a world without language?

Too right. There won't be any fact of the matter of implicit conventions, of course, but one that seems to me to be just as widely asserted is that language presupposes a world already formed/carved/sorted in the terms of the language. (Don't blame me.) — bongo fury

Not "in the terms of the language". For example, scientific language changed as Newtonian mechanics was superseded by relativity and quantum mechanics, and will presumably continue to change in the future. But the world itself didn't change on account of humans using different language to talk about it.

That convention, both in science and in ordinary communication, has been useful.

The way out is to see that we are social animals who think and talk with symbols, whose wholly fictional connection to things is a matter we have to (and learn successfully to) constantly convince each other we are agreed about. Often we can agree that a word points at an abstraction, and often that is because doing so serves as a shorthand for reference to all of the more concrete instances abstracted from. — bongo fury

Then it seems your position precludes any rational basis for agreement. That is, people can agree on one fiction or another (per their preference), but not on how the world is independent of their agreement. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsDo you mean,

Now it seems to me that if two things are [not similarnon-similar in a sense of similarity] independent of language, then applying the same term to them doesn't make them similar.

— Andrew M

?

To the nominalist ("extreme" :lol: or not) this sounds metaphysical, although possibly redeemable in terms of object- and meta-language. Are you in the habit of saying "F=ma, independent of language"? Would you then mean independent of any language (the talk just got metaphysical but through no fault of nominalism), or just higher-level ones? — bongo fury

I meant it as shorthand for "independent of our linguistic propensities to apply the same term to them" as in the original Oxford Reference quote.

And, no, I wouldn't normally say "independent of language" because I understand it as an implicit convention in ordinary communication. That is, that language presupposes a world for language to be about.

For example, would you agree that two brontosaurus dinosaurs were similar in the sense of both having four legs before the emergence of human beings and human language?

If you mean,

Now it seems to me that if two things are [notnever] similar independent of language, then applying the same term to them doesn't make them similar.

— Andrew M

then of course the nominalist disagrees, and is interested in how language creates a similarity between the things. — bongo fury

So I'm unclear on how you would make sense of that project. It seems to require rejecting the convention I stated above, but for what purpose?

On the other hand, if two things are similarindependent of language, that doesn't imply the existence of a third entity for a language term to denote.

— Andrew M

But it does often coincide with use of a general term applying to both: a shared name (or adjective or verb). Then we are presented (sooner or later) with the opportunity to reinterpret the general term as singular, and with questions about how such a choice affects just what entities (e.g. a third one) are thereby implied. Platonist and nominalist might come down on either side of the choice as expected, but the modern nominalist is often prepared to be agnostic on the matter, since there is no fact about it, and because a singular reading (referring to a collective or whole or essence or quality) might be a shorthand for the general reading (referring distributively to all the individual instances). — bongo fury

I assume there is no empirical fact about it, in the sense of an observable difference. However there may be logical (or absurdity) arguments against one or the other of those choices. For example, the Third Man argument which is an infinite regress argument against Plato's Theory of Forms. -

Gettier Problem ContradictionNote that the average person knows nothing about JTB. And most of us, especially when not doing philosophy, normally use language conventionally. So Gettier didn't need to base his analysis on people's stated intuitions (which may well be weak), but on how people conventionally speak in the relevant scenarios. And you may be surprised at how much information you can extract from such an analysis.

Here's a possible scenario for Russell's clock (based on an earlier thread).

(1) Alice: What's the time?

(2) Bob: 3pm.

(3) Alice: How do you know?

(4) Bob: I looked at the clock just now

(5) Alice: Ah, OK.

(6) Carol: That clock is broken.

(7) Alice: Oh. So what time is it?

(8) Carol: I'll check the internet time clock ... It actually is 3pm.

(9) Alice: Really? (laughs) OK.

Note that the word "know" is only used once in that exchange. Yet an analysis shows, for Alice, a Gettiered JTB (at 5) and knowledge (at 9). -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsYes. The Platonist embellishes similarities as (capital-N, entity) Names, the Nominalist reduces similarities to (small-n, paper draft [*]) names. Neither side challenges that reclassification nor sheds any light on similarity.

— Andrew M

Yes, I know you think that outcome is inevitable, but I was wondering where, or if, you were finding any examples. — bongo fury

OK, you specifically mentioned Goodman. From Oxford Reference:

Goodman is associated with an extreme nominalism, or mistrust of any appeal to a notion of the similarity between two things, when this is thought of as independent of our linguistic propensities to apply the same term to them. — Oxford Reference - Quick Reference

Now it seems to me that if two things are not similar independent of language, then applying the same term to them doesn't make them similar.

On the other hand, if two things are similar independent of language, that doesn't imply the existence of a third entity for a language term to denote.

The issue in both cases is that similarity doesn't imply a name at all, whether in a Platonic or Nominal sense. -

Gettier Problem ContradictionArguably, to say that Smith lacks knowledge, Gettier needs a theory of knowledge based on which he can make such a claim, no? What's this theory is all I'm asking. — TheMadFool

Gettier didn't need a theory (beyond the JTB theory he was challenging), he just needed to be aware of people's ordinary use of the terms "know", "knowledge", etc. He was able to identify scenarios where people regarded a person's belief as true and justifiably held, but they didn't also regard it as knowledge (also subsequently shown experimentally across different cultures). Note that he wasn't the first to recognize this - see Russell's stopped clock case which is perhaps a more straightforward scenario.

That's the parallel of people observing Mercury's position and noticing that it wasn't where Newton's theory said it should be. Those people didn't have a better theory - that would have to wait until Einstein came along.

As for what a better theory might be, I think the "no false premises" approach is basically right (but note the possible objections at that link). -

Gettier Problem ContradictionUnacceptable for the reason that the Alice-Bob story still employs the JTB theory, the very theory that is supposedly wrong or incomplete. — TheMadFool

The Alice-Bob story is an everyday scenario where Bob forms his belief that it is raining for a legitimate reason (i.e., he justifiably forms his belief). That's the kind of scenario that a theory of knowledge is intended to describe, whether it's JTB or any other theory.

Now consider a planet orbiting a star. That can be described using Newton's theory of gravity. However it turns out that there are cases (such as with Mercury's orbit) where Newton's theory makes the wrong prediction.

Just as we can observe a planet's orbit, so we can observe how people use knowledge terms in everyday scenarios. In a Gettier scenario, JTB makes the wrong prediction (i.e., it predicts that Smith has knowledge whereas people don't regard Smith's belief as knowledge). -

Gettier Problem Contradiction1. What definition of justification is Gettier using? — TheMadFool

Just what you might expect in ordinary, everyday life. If Alice looks out the window and says it is raining outside then Bob, in the next room, has justification for believing it's raining outside. He doesn't need to also verify all the relevant premises that that belief is based on (e.g., that Alice isn't hallucinating, or that the water is not coming from a garden hose unbeknownst to Alice, etc.), which would be impractical.

2. We know for sure that Gettier is using the JTB theory to infer that Smith has a justified, true belief but there's another definition of knowledge that makes Gettier claim that Smith doesn't have knowledge. What is this "another definition of knowledge"? — TheMadFool

People's common intuitions about knowledge with respect to Gettier scenarios.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gettier_problem#Experimental_research -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsThe Nominalist, in their attempt to exorcise the Platonist spirits, can end up being a mirror-image or dual of the Platonist because of a deeper framing of the problem that neither side has recognized.

— Andrew M

In the fond imaginings of a third kind of philosopher, yes of course... or, do you have examples of such a mirror symmetry? — bongo fury

Yes. The Platonist embellishes similarities as (capital-N, entity) Names, the Nominalist reduces similarities to (small-n, paper draft [*]) names. Neither side challenges that reclassification nor sheds any light on similarity.

Lazerowitz does begin with the same too-easy claim, but then proceeds with a perfectly useful analysis that might as well call itself nominalist, like the Quine piece cited. (I'm still not sure you grasped the point of the quoted extract nor Lazerowitz's point about it.) So, examples of the alleged symmetry are lacking. — bongo fury

You can call it nominalist, but are you telling us any more than how you're classifying it? ;-) Quine is reclassifying general terms as names there because it's convenient for the logic he is developing. That's fine but it doesn't tell us anything about the ontology of the world, only about his preference.

What we do know is that in the course of our investigations of the world, we can identify similarities and differences in things. That's the natural home that those terms arise in and by which we then classify things (according to our various purposes). So classification itself depends on a prior notion of similarity and difference.

Which problem? The "problem" of universals? The modern nominalist exchanges that for a more interesting investigation into all of the implications of shared naming... — bongo fury

Lazerowitz's analysis is interesting and informative because he's investigating and forming a hypothesis about what philosophers are doing, not discussing how to classify similarity (per the Problem of Universals). More broadly, an investigation and analysis of how language is used in various contexts is also interesting and informative. But, as Wittgenstein notes (quote below), that is not Nominalism.

foundations of math, psychology of consciousness, theory of reference, theory of learning, logic of induction, semiotics etc

— bongo fury

Is the material world supposed lacking in resources for these investigations? — bongo fury

Per "material", yes, which is one side of a Platonic dualist framing that reiterates the reductionism implicit in Nominalism. Similarity, for Nominalists, reduces to just names. Which precludes even the possibility of investigation.

--

[*]We are not analyzing a phenomenon (e.g. thought) but a concept (e.g. that of thinking), and therefore the use of a word. So it may look as if what we were doing were Nominalism. Nominalists make the mistake of interpreting all words as names, and so of not really describing their use, but only, so to speak, giving a paper draft on such a description. — L. Wittgenstein, PI §383 -

Gettier Problem ContradictionWhat is the role of luck in Smith's situation exactly? Firstly, the fact that truth is a condition in JTB theory in addition to justification suggests that justification alone is not enough to establish truth - in other words, the necessity of truth as an extra condition implies a forethought that luck plays a part in knowledge, no? Otherwise, why include truth at all as part of knowledge in the JTB theory? If that's the case, Gettier hasn't actually noticed anything that wasn't there already. However, it's true that Gettier laid it [the problem of luck] wide open for all to see. — TheMadFool

The luck element is that some person other than Jones happened to fulfill the justification criteria. Smith's belief was true despite the false premise.

If Jones had got the job, then Smith's belief is attributed to his having met that standard of justification before forming his belief, not luck. The purpose of the justification condition is not to guarantee the truth, which would be impractical, if not impossible (and would make the truth condition redundant). It's instead to make sure that only people who have made an appropriate effort in forming their beliefs have knowledge attributed to them.

Secondly, when you say "Smith's reasoning depended on a false premise" aren't you also saying, as a consequence, that Smith's justification is flawed or, to make the long story short, Smith is actually unjustified? Doesn't that contradict the JTB theory and mean that Smith actually doen't have knowledge but not because of a reason other than failing to satisfy the conditions of the JTB theory as Gettier seems to be implying? — TheMadFool

No, that would just be using a different definition of "justified" to what Gettier is using. The case assumes that Smith is justified in believing that Jones will get the job and has ten coins in his pocket (which is a justified false belief and so not knowledge). So Smith is also justified in believing that a person with ten coins in his pocket will get the job (which is a justified, true belief but also not knowledge because it derives from the earlier false belief). -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsYou jest? (Forgive my irony failure if so.) — bongo fury

I was going for metaphor. :-) For the jest, see here...

The broader point is that it is easy to be mislead by language and there are plenty of examples of this in the history of philosophy. The irony is that it can happen to any of us even when we think we're attending to it. The Nominalist, in their attempt to exorcise the Platonist spirits, can end up being a mirror-image or dual of the Platonist because of a deeper framing of the problem that neither side has recognized.

So Lazerowitz's strategy here is to expose the roots of the problem itself, not take a side in the dispute.

In effect, the Platonist envisages another realm (of a less tangible sort) that they frame as part of a dual - the material and immaterial. The Nominalist applies their razor to the immaterial side of that duality (because ghosts, extravagence, etc.), but find they are left with an impoverished material world that provides no resources for solving the problem. So the dispute seems unresolvable and interminable.

But the root problem is not that the Platonist has constructed something out of whole cloth that needs to be excised. It's that they have reallocated some things away from their natural home.

Recognizing that dissolves the Problem of Universals - there's no longer a side that needs to be defended.

Wasn't Quine briefly gesturing to a nominalist translation of sets-talk in terms of shared naming before admitting sets as entities for the sake of exposition of the standard Platonism? And then wasn't Lazerowitz seeing the gesture as support for his proposal: where possible, and in a spirit of charity, read Platonists as positing universals as a shorthand for shared naming? — bongo fury

I think more than that, Lazerowitz claims that what the philosopher does "is concealed from himself as well as others" and even that philosophical views are the vehicles for expressing "unconscious fantasies". At the very least it's a call to self-awareness when we use language. -

Immaterial substancesAhhhhh okay no, I don't mean it is undetectable insofar as it is beyond our current or future technological capabilities. I mean it's coupling to all other fields is zero even in theory. That would be something new. — Kenosha Kid

Fair enough. It seems to me that belief can still be justified on balance of considerations. -

Gettier Problem ContradictionMy understanding of the problem is that Smith fails (1) — Kenosha Kid

That would be this:

Affirmations of the JTB account: This response affirms the JTB account of knowledge, but rejects Gettier cases. Typically, the proponent of this response rejects Gettier cases because, they say, Gettier cases involve insufficient levels of justification. Knowledge actually requires higher levels of justification than Gettier cases involve. — Responses to Gettier - Wikipedia

Whereas Gettier's intention was to setup the case such that Smith's belief was justified and true, but not knowledge. If Smith's belief were unjustified, the case wouldn't undermine the JTB account of knowledge. -

Immaterial substancesThat is a falsifiable proposition. — Kenosha Kid

Yes, but I'm not sure that's essential for justification. You might justifiably believe it will rain tomorrow based on the weather report. Turns out it doesn't in this case. But that doesn't mean that you can't justifiably believe weather reports in the future.

An undetected field doesn't seem like a ghost in the water tank. We've detected plenty of other fields - this particular one just happens to be beyond our ability to test for. The upside considerations of the theory would seem to outweigh this particular downside. -

Gettier Problem ContradictionIt's clear that:

1. Smith is justified in believing the person who gets the job has 10 coins in his pocket

2. It's true that the person who gets the job has 10 coins in his pocket is true

3. Smith believes that the person who gets the job has 10 coins in his pocket

In other words Smith has knowledge concerning the person who gets the job. — TheMadFool

No, what Gettier has shown here is that Smith can have a justified true belief, yet fail to have knowledge (since Smith's belief was true by luck). So there must be some other further condition required for knowledge. Gettier doesn't elaborate on what that further condition might be, but the problem here is that Smith's reasoning depended on a false premise, namely, that Jones would get the job. So a candidate fourth condition would be that knowledge doesn't depend on false premises. -

Immaterial substancesWe usually talk about such things in terms of justifiability. I'm particularly a hardliner on this, so I was wondering what it would take for me to believe in something that cannot be even indirectly experienced. — Kenosha Kid

No easy answer. But it seems to me justifiable just as believing the sun will rise tomorrow (or in a thousand years) is justifiable even though it hasn't been experienced. -

Yes, No... True, False.. Zero or One.. does exist something in the middle?I would like to ask if, in terms of truth, do we only have true or false, zero or one, yes or no, or does exist something else in the middle describing something between the two. — mads

I think as a general rule, the Law of Excluded Middle applies. But there can be exceptions, e.g., fuzzy logic, or loaded questions like "Have you stopped beating your wife?" -

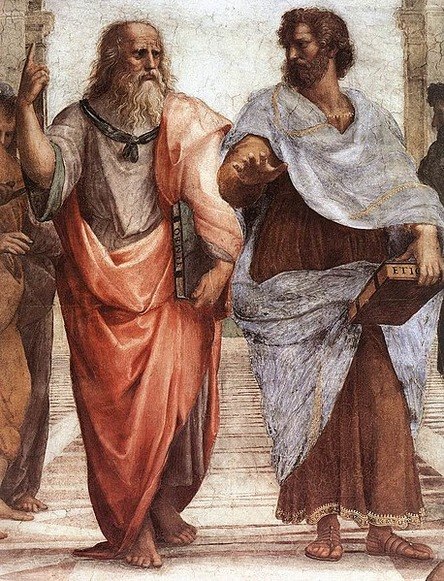

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsThe Existence of Universals (1946) — SophistiCat

Lazerowitz's reclassification hypothesis at the end of that paper seems apt for this thread. Which is the philosophical proposal that an abstract word, such as "horse", can be reclassified as a proper name for an abstract entity.

He gives an example of this from Quine:

It is convenient, however, to regard such general terms [ 'wise', 'city' ] as names on the same footing as 'Socrates' and 'Paris': names each of a single specific entity, though a less tangible entity than the man Socrates or the town Boston. — W.V. Quine, Mathematical Logic

Understood metaphysically, it opens up a whole new world that is otherwise hidden to the ordinary person. See, for example, Plato's Allegory of the Cave. -

Immaterial substancesOne reason might be that nothing has the property of coupling to the radion field (unlikely in this case), which made me wonder: if something like KK theory were formalised that predicted two new fields -- one detectable and detected, the other undetectable even in principle -- would the predictiveness and simplicity of the theory justify belief in something out there that we cannot possibly detect under any circumstances? — Kenosha Kid

Given its predictiveness and simplicity (and perhaps also its explanatory power), I think it would have to be a strong contender. That the field is undetectable doesn't imply it's not there, so the theory could nonetheless be true.

But given that it is a physical theory, shouldn't we expect the field to be coupled to other things in some way? Otherwise what would it be contributing to the theory?

If not, perhaps the theory would lend itself to different interpretations, similar to QM. Which I think would be an indication that the theory is still lacking in some respect. -

Immaterial substancesIf someone discovered a grand unified field theory that yielded:

all Standard Model fields exactly

one unknown material field (should couple to our material world)

one unknown immaterial field (should not couple to our material world)

such that no one of the above can be removed and the model stand, and if we then empirically verify the unknown material field (in, say, a particle accelerator), would that justify some credence in the immaterial one? I'm inclined to think it does. — Kenosha Kid

I find it difficult to envisage what an "unknown immaterial field" could be. If the GUT requires it, then isn't it then coupled to the world by virtue of that? Or perhaps you mean something like the Many Worlds interpretation of QM where the copies of you are undetectable - in a sense uncoupled from what is directly observable? -

Immaterial substancesit's instead part of the formal machinery

— Andrew M

where 'machinery' is a metaphor for a network of concepts and predictions that arise from them. — Wayfarer

Yes, and you can probably extract everyone's view of universals right there.

Contra Nominalism, reference frames aren't just in the mind or in language, they are a formal aspect of the world being investigated. And contra mathematical Platonism, they are not prior to or separate from the world. -

Immaterial substancesQuick defining of terms.

"Material" here is in the contemporary sense that if it is affected by and/or affects material things, it comes under the material world's purview (e.g. spacetime, electric fields, etc.) In short, if we can detect it, even indirectly, it gets classed as material. — Kenosha Kid

The idea of reference frames strikes me as material, as does the actual thing it represents. — Kenosha Kid

As you know, reference frames are a formalism that abstract over the systems they stand for. Physicists use that formalism to say that when you do this experiment, this outcome is predicted.

It is those observable systems that ground the formalism.

Now you're just saying that that grounding and use is what makes them material - physicists couldn't explain their experiments without them.

That's OK. But it doesn't quite fit your definition above. A reference frame isn't itself detectable, it's instead part of the formal machinery that physicists use to detect things. -

Sending People Through Double SlitsThis is not an argument from quantum theory, I gather, more a philosophical argument as to how quantum mechanics ought to be. — Kenosha Kid

It's a relational interpretation (which the paper uses, see for example reference [23] in the earlier quote referring to Rovelli's RQM).

The double slit experiment suggests that electron collapse at the slit only occurs if we attempt to observe it at the slit, e.g. if we put something in the way of the slit that causes earlier collapse, such as an electron detector. — Kenosha Kid

Right, the electron detector provides which-way information that collapses the electron superposition in the lab observer's reference frame.

But that doesn't imply anything about what happens in the electron's reference frame when there is no detector. On a relational view, since an interaction occurs at the slit, collapse occurs in both the electron and apparatus reference frames. But collapse doesn't occur for the lab observer since which-way information is not available in the lab-observer's reference frame. So collapse is reference frame-dependent. This is analogous to a Wigner's Friend experiment where a definite measurement event occurs in the friend's reference frame but remains in superposition in Wigner's reference frame. -

Sending People Through Double SlitsBut the electron doesn't 'go' in its rest frame, by lieu of a) it's its rest frame and b) its momentum is undefined. (That said, the paper isn't bothered about rest frames as much as un-superposed frames.) At any time, either slits already have a nonzero probability of being behind the electron. — Kenosha Kid

OK, but the puzzle is to account for what happens when the two apparatus slits go past the electron in the electron's rest frame.

If the apparatus remains in superposition when the slits go past the electron, then the apparatus should similarly remain in superposition when the back screen hits the electron. That is, no definite measurement event would ever occur in the electron's reference frame.

If a definite measurement event does occur at the back screen in the electron's reference frame then a definite measurement event should also have occurred at the slit. It seems to be a similar kind of physical interaction and so should be treated similarly.

As I see it, the electron does go through a specific slit in the electron's reference frame. That is consistent with the relational approach that the paper uses (see quote below), which is that whether a definite measurement occurs or not depends on the frame of reference.

We find that a quantum state and its features — such as superposition and entanglement — are only defined relative to the chosen reference frame, in the spirit of the relational description of physics [16–19, 23, 24]. For example, a quantum system which is in a well-localised state of an observable for a certain observer may, for another observer, be in a superposition of two or more states or even entangled with the first observer. — Quantum mechanics and the covariance of physical laws in quantum reference frames - Giacomini, Castro-Ruiz, Brukner -

Sending People Through Double SlitsAh, here's the preprint: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.07207.pdf — Kenosha Kid

Nice find. Also here's a brief media summary of that paper, aptly titled How does a quantum particle see the world?

Unfortunately the paper doesn't directly address the double-slit experiment. It seems to me that even if the apparatus is in superposition in the electron's reference frame, the electron still needs to go through one of the slits which is then effectively an interaction with the apparatus. However the which-way information is not available to the observer (since there are no detectors on the slits), so the process remains unitary in the observer's reference frame.

This is similar to the Wigner's friend thought experiment, where Wigner's friend makes a definite measurement while the process remains unitary from Wigner's perspective. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsIn the conventional story, it is explained to Gilbert that the University is the way the buildings are organized.

— Andrew M

Except that a university is also a social organization, and organizations are more difficult to be relegate to a name for a group of individuals, land and buildings, since the social structure has an important effect on society. — Marchesk

That's right. Gilbert is not a Nominalist in that story. -

Lazerowitz's three-tiered structure of metaphysicsIt's worth pointing out that the point here is that both the claims that universals do and don't exist are equally confused – that is, 'nominalism' is as much a metaphysical thesis in this sense as 'realism.' — Snakes Alive

You requested some stories about universals...

The stories all begin with Gilbert visiting Oxford and remarking that he had seen the colleges and the libraries, but was wondering where the University was.

In the Platonist story, the University resides in the realm of the Forms and the colleges and libraries are merely a dim reflection of that Ideal. Gilbert travels to the realm of the Forms and has a mind-bending experience. Eventually he comes back down to Earth to enlighten his fellow compatriots about the Ideal University.

In the Nominalist story, there is no University, only buildings in a desert landscape. Gilbert learns that the University is merely an arbitrary artifact of human language and thought. Gilbert wanders around in perpetual confusion, unable to find order or meaning in anything.

In the conventional story, it is explained to Gilbert that the University is the way the buildings are organized. Gilbert enrolls, earns a degree, and makes valuable contributions in the philosophy of language and mind. -

Newcomb's Paradox - Why would anyone pick two boxes?My question is why would anyone choose two boxes if the predictor is infallible? — Jacykow

They shouldn't. Since the predictor is infallible, there can only be two possible outcomes:

- player chooses box B only; box B contains $1,000,000

- player chooses both boxes A and B; box B is empty

I think what makes the paradox interesting is that it's not the case that by choosing both boxes the player will win $1,000 more than by choosing one box. That's the two-boxer intuition, but it doesn't apply here. So we might wonder how the world could be like that. And since only one of those two conditions can be true on conventional assumptions (i.e., either box B contains $1,000,000 or else it is empty) it further seems that the player doesn't have a real choice either.

However an alternative approach is to model the scenario using quantum entanglement. This is done by preparing two qubits in the following superposition state (called a Bell state):

|00> + |11>

That corresponds to the above conditions in Newcomb's paradox. The first qubit (i.e., the first digit of each superposition state) represents the player's choice: 0 for choosing box B only, 1 for for choosing both boxes. The second qubit represents the amount of money in Box B: 0 for $1,000,000, 1 for $0. So describing the superposition in terms of Newcomb's paradox:

|player chooses box B only; box B contains $1000000> + |player chooses both boxes A and B; box B is empty>

If the player chooses Box B only (i.e., measures 0 on the first qubit [*]), that collapses the superposition to:

|player chooses box B only; box B contains $1000000>

Thus, it is certain that box B contains $1,000,000. That is, when the second qubit is measured, it will be 0.

Similarly, if the player chooses both boxes A and B (i.e., measures 1 on the first qubit [*]), that collapses the superposition to:

|player chooses both boxes A and B; box B is empty>

Thus, it is certain that box B is empty. That is, when the second qubit is measured, it will be 1.

To say this in a different way, Newcomb's paradox is like flipping a pair of fair coins a thousand times where the result is always HH or TT, but never HT or TH. Classically, that is extremely unlikely. But using the above Bell state in a quantum experiment, the result is certain. So what makes the predictor infallible here is not that he knows whether the player will flip heads or tails. He instead just knows that the paired coin flips are always correlated. Similarly, the Newcomb predictor doesn't need to know what the player's choice will be, he just knows that the player's choice and the contents of box B will be correlated.

--

[*] Important caveat: In quantum experiments, the measurement of a qubit in superposition randomly returns 0 or 1. So on this model the player makes their choice, in effect, by flipping a coin. That is, they make a measurement on the first qubit which randomly returns 0 or 1. As a result of the entanglement, the predicted outcome from measuring the second qubit is certain.

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum