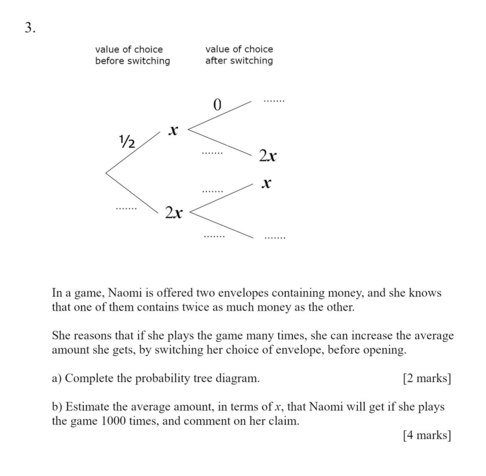

Comments

-

Why be moral?22% of people believe that eating meat is immoral and 88% don't. — Michael

10% are confused. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/14873/what-could-solve-the-hard-problem-of-consciousness/p1

With or without neuroscience we have the Chinese Room to thank for explaining that a proper semantics (skill in pointing words and other symbols at things in the world, as opposed to merely co-ordinating them with each other) is what makes the difference between a neural network having or not having consciousness. (I.e. between it tending or not tending to think it has a theatre in the head.)

That just leaves unsolved those other, truly hard problems of philosophy that you allude to. Time and so on. -

Would P-Zombies have Children?1. A p-zombie is physically identical to us except that it has no consciousness — Michael

So, physically identical except in respect of its lacking consciousness, possibly physical?

Or, physically identical but different non-physically, in respect of its lacking consciousness, presumed non-physical? -

Are words more than their symbols?

Touche.Everybody seems to think we're all the same. It's really hard to grasp that we aren't. — frank -

Are words more than their symbols?I get subtle movements, which could be described as shivers as you say. Is this what they mean by thinking in words or an inner monologue, where neither the act of speaking nor any actual words are involved? — NOS4A2

It's what they mean by "sub-vocalisation", at least.

There is nothing occurring that I could call a voice. — NOS4A2

Why not, if it resembles speech in respect of its graph of intensity against time?

Only some people have it. — frank

I think they are either confused by the unwarranted emphasis on sub-monologue to the exclusion of sub-dialogue (far more typical I expect) or they are reacting consciously or otherwise against the unwarranted inference to actual internal speech. -

Are words more than their symbols?Don't you have brain shivers that appear to rehearse likely conversations with other speakers?

I mean, don't you find your brain rehearsing the kinds of shivering by which it might recognise and respond effectively to other speakers' likely comments about views you hold? Shivers that tend to proceed with time-intensity envelopes fairly analogous to word-sounds?

So, I mean, monologues aside, don't you even have quote internal dialogues unquote? (Not actual ones, agreed. Probably.) -

How Do You Personally Learn?

As those cats would no doubt advise: the best possible method of learning is play, but at the same time it's crucial that newly acquired knowledge be consolidated through sleep. -

Poll: Evolution of consciousness by natural selectionDo you believe that billiard balls experience impacts in the same sense that football players experience impacts? — petrichor

In the more mundane of the two senses which you are right to separate, yes. (The sense of "undergo".) Balls and players both.

Are you sure that sense is irrelevant? Couldn't it be the ground of your incredulity here?

I can't imagine how, if there is actually no experience, there could be a situation where it nevertheless seems that there is an experience. — petrichor

That sense removed, aren't we left with

I can't imagine how, if there is actually no [theatre in the head], there could be a situation where it nevertheless seems that there is [a theatre in the head]. — petrichor

? -

Poll: Evolution of consciousness by natural selectionI have a hard time with eliminativism or illusionism. I can't imagine how, if there is actually no experience, there could be a situation where it nevertheless seems that there is an experience. — petrichor

Experience is undeniable, yes. But unconscious billiard balls can experience impacts, and unconscious computers can experience changes in state or configuration, analogous to our messier brain shivers.

What is deniable is that a shiver experienced by the brain is ever actually accompanied by a corresponding picture in the brain, or world in the brain. -

Is there a term for this type of fallacious argument?Well neither of these pages,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Is%E2%80%93ought_problem?wprov=sfla1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychological_nativism?wprov=sfla1

has the other in its See Also list, but I feel there might be a connection. -

Could we be living in a simulation?More generally, there is a literal world of difference between a matrix world in which real humans are immersed in a digital world that they believe is real, and a simulated world with simulated humans - — unenlightened

Then again, it's conceivable that simulated humans could be real AI's, immersed in a virtual digital world. Conceivably, they might be fooled.

(Though, more realistically, they would probably need to interact with a real environment in order to develop a proper semantics, and be fooled about anything, in what we ought recognise as a conscious, and hence relevant, way.)

I do agree that a literal world of difference remains, though, between that conceivable scenario, and simulation hypothesising (Bostrom et al), in which fictional worlds with fictional humans magically become real.

There can be no escape from the simulation for simulated persons, if such are possible, and since for them it is their only world, for them it is reality, and the programmer is God. — unenlightened

:100: :lol: -

Reading "The Laws of Form", by George Spencer-Brown.(you don't have to agree, I'm just giving shape to the way the axioms work with a familiar example.) — unenlightened

I get a different shape? More like, axiom 1 is about saying a thing (e.g. "Romeo!")... which, if you do it again, is only to reinforce that first statement (or state-naming!).

While, axiom 2 is about changing sides on the issue ("rather, thou art some other, that smell as sweet")... which, if you do it again, is only to undo that first change. And probably end up where it started.

Assertion and negation, basically? -

How ChatGPT works.A semantic grammar is a semantic syntax. So not necessarily a true semantics. Not necessarily joining in the elaborate social game of relating maps to territories. Not necessarily understanding. Possibly becoming merely (albeit amazingly) skilled in relating maps to other maps.

-

Is indirect realism self undermining?whether or not we should describe perception as "seeing representations" or "seeing the external world stimulus" is an irrelevant issue of semantics. It's like arguing over whether we feel pain or feel the fire. — Michael

So it's a crucial issue of semantics. Should the psychology admit internal representations, as well as external representations and internal brain shivers? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Yes. The broken leg is the trauma. The brain activity (or the mental phenomena it causes) is the pain. — Michael

Ok. The broken leg is trauma. The brain activity (the recognising the broken leg as an instance of trauma) is the feeling pain.

And yet as I said we can recognise trauma without "feeling pain" (e.g. congenital insensitivity to pain) — Michael

Sure. The associations effected by merely intellectual recognition of the trauma hardly overlap at all with the associations we are inclined to call "feeling pain", which are informed directly by stimulation of nerves in the site of the trauma.

and we can feel pain without recognising trauma (e.g. headaches). — Michael

Sure. We can recognise wrongly. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Hmm so you were distinguishing neural alarm from bodily trauma?

-

Is indirect realism self undermining?We don’t just associate pain with trauma; we feel pain in response to trauma. They are two separate things. — Michael

I'm suggesting the pain is the recognition of the trauma as an instance of a kind of thing, e.g. of trauma. It is the association. Sure it's separate from the trauma. It might be caused by the trauma. But not from or by the pain. It is the pain. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I don’t need a language to be in pain. Pre-linguistic humans had headaches. — Michael

They suffered the trauma. My car suffers trauma. And pain, but only metaphorically. They, though, probably also had enough symbolic ability to associate it with trauma in general. Which is how we suffer pain literally. Perhaps. Plausibly. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Sure. I'm not totally averse to saying that mental phenomena just is brain activity. What I'm averse to is the claim that being in pain has something to do with me saying "I am in pain" — Michael

But then, applying that to the snooker balls, you're averse to saying that seeing the ball as red has something to do with associating it with red surfaces generally? For example by reaching for the word "red". I thought you might be. Slightly surprised that you reply with "sure".

If you're not totally averse to that, though, how about that being in pain is associating the bodily trauma in question with bodily trauma in general? For example by reaching for the word "pain". -

Is indirect realism self undermining?would that be tantamount to accepting that gravity is mystical? — frank

There's mystical and there's mystical. There's an invisible pull between two bodies proportional to their masses, and there's a picture show in the head.

As for SDR, I'm not at all sure I'm on side with any brand of realism, inasmuch as they mostly seem to discuss the possibility of some kind of inner ghost making contact with the outer world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?You don't have to think of experience as a collection of ghosts, though. You can just note that you do see red, and leave it unexplained exactly how. — frank

That seems tantamount to accepting the ghost as ghost? Which could turn out to be appropriate, of course. I'm just pointing out an alternative. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?You put a red ball and a blue ball in front of me. I can see that one is red and one is blue. I don't need to do or say anything that you can interpret as me "seeing red" or "seeing blue". — Michael

But perhaps you need to have brain activity that succeeds in associating the red ball with red surfaces generally, and the blue ball with blue surfaces generally?

Having red or blue mental images in the brain, to meet that purpose, is kind of having a ghost in the machine.

Having the brain reach for suitable words or pictures, isn't. And, even better, it suggests a likely origin of our tendency to imagine that we accommodate the ghostly entities. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Again, you seem to fail to understand the use-mention distinction.

But this isn't the main point. — Michael

Perhaps yes it is, and no we don't fail. We, the people disputing the reality of private experience, understand that seeing colours is using (hence reaching for) words and pictures in order to mention (refer to, and thereby identify, classify, compare and order) visual stimuli.

This symbolic skill does tend to thrive on casual confusion of symbol and object, such as the kind usefully diagnosed as use-mention, but also (by the way, just saying...) the kind that confuses either symbol or object with brain shiver.

Without language, your target image might illicit responses that deserved classifying as a nascent form of recognition or comparison or classification of colours. Perhaps an animal would be reminded (as it were) of a face, in response to the whole set of local contrasts. But to imagine that all of the concentric rings would be identified as instances of separate classes of stimuli... That implies language, proper. -

Exploring the artificially intelligent mind of GPT4Searle argues that even though the person in the room can produce responses that appear to be intelligent to someone who does not understand Chinese, — Bot to Banno

Searle's requirement, to the contrary, that the room should convince even Chinese speakers, always seemed somewhat audacious. Until now?

While the person in the Chinese Room follows a static set of rules to manipulate symbols, GPT-4's neural network is capable of generalization, learning, and adaptation based on the data it has been trained on. This makes GPT-4 more sophisticated and flexible than the static rule-based system in the Chinese Room. — Bot to Pierre-Normand

Did Searle concede that the rules followed were static? If so, was 'static' meant in a sense contradicted by the present (listed) capabilities? I had the impression it would have allowed for enough development and sophistication as to lead exactly to those capabilities, which would be necessary to convince a semantically competent audience. For 'static' read 'statistical'?

Then GPT-4 is nothing not envisaged in Searle's account. -

Who Perceives What?When I see a photo of a tree, I indirectly perceive the tree, but directly perceive the photo, for example. — NOS4A2

Does the camera, producing the photo, directly perceive the tree?

Also.

Is it different for words? When you see the name "Fido", do you indirectly perceive the dog?

Or is it more relevant to ask: when you read a description of Fido, do you indirectly perceive the dog? -

Who Perceives What?

I'm not sure. I recall @Terrapin Station arguing for that kind of direct realism, and likening the alleged directness of his alleged mentalrepresentationsawareness to the fidelity commonly attributed to photos over and above hand-drawn painting. If I read him right.

I'm curious whether the OP's point is the same (boo) or different (hooray).

... Having now checked: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/297414

@Terrapin Station denies his awareness-picture-in-the-head is a representation-picture-in-the-head. I never quite saw the difference. Shame we can't ask him. -

Who Perceives What?Representations, what more can be/should be said about them? — Agent Smith

That they aren't in the head. -

Welcome Robot OverlordsChatGPT applies a statistical algorithm, — Banno

Exactly like a non-Chinese speaker using a manual of character combination to hold a conversation with Chinese speakers outside the room, without understanding it at all?

bongo fury

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum