Comments

-

Decidability and TruthQuestion 1) Can a statement be true or false if it is not possible to determine which it is, even in principle?

Statement 1) Since there is no evidence whether it is possible to determine the truth or falseness of the multiverse interpretation of QM, should that interpretation be given serious consideration as a scientific theory? — T Clark

There may be no evidence today determining the truth or falseness of the multiverse interpretation of QM, but there may be evidence next year. As @Philosophim wrote: "Maybe humanity will discover the truth about multiverse theory, and maybe they won't"

Question 1) refers to a proposition that it is not possible even in principle to determine whether true or false.

As it may be possible to determine whether the proposition "there is a multiverse" is true or false, it is therefore possible in principle to determine that the proposition "there is a multiverse" is true or false.

Therefore, question 1) has no bearing on statement 1).

(Although I am not sure everyone would agree that there is no evidence for a multiverse) -

What is it that gives symbols meaning?those things within an art work that draw us in and with which we make an emotional connection. — TheVeryIdea

On seeing Munch's Scream, the screaming face has an immediate emotional meaning.

But the screaming face also has a symbolic meaning, a symbol of of despair, which, when one reflects on it, may result in the remembrance of an emotion of despair.

The question is, when I look at The Scream, am I looking at an analogical representation having immediate emotional meaning or a symbolic representation having a cerebral symbolic meaning which may subsequently result in an emotional meaning. -

What is it that gives symbols meaning?one might expect everyone to have similar preferences — TheVeryIdea

Wikipedia Novelty Seeking writes - "In psychology, novelty seeking (NS) is a personality trait associated with exploratory activity in response to novel stimulation, impulsive decision making, extravagance in approach to reward cues, quick loss of temper, and avoidance of frustration. Although the exact causes for novelty seeking behaviours is unknown, there may be a link to genetics". This novelty gene is thought to appear in a portion of the human population, something that may explain the differences in our temperaments.

IE, as the worlds of art are fueled by a thirst for novelty, novel creations also carry their own aesthetic merit.

However other more complex symbology, which is often seen as operating at a higher level, is more intellectual and less evolutionary, less base-instinct and perhaps that is why we value it more. — TheVeryIdea

As every object has a temperature, every object is an artwork and has an aesthetic, but not all artworks are of the same quality, as not every object is of the same temperature.

Some artwork appeals to our simplistic nature, such as Bob Ross's Mountain with Lake, and some artwork appeals to our more sophisticated nature, such as Monet's Sunset in Venice.

Simple is different to simplistic, in that Matisse's Cut-Outs are simple, yet sophisticated.

However, the intellect is a product of evolution, meaning that even the most sophisticated aesthetic is still a product of evolution. -

What is it that gives symbols meaning?why some things make a connection with an audience and some don't — TheVeryIdea

Why does any sight, sound, touch, taste or smell give rise to a subjective emotion. Such as the sight of a sunset, the sound of a bird, the touch of velvet, the taste of wine or the smell of a rose.

The sight of a sunset may arouse in the observer an emotion of delight. Monet's Sunset in Venice may arouse in the observer an emotion of delight. The sunset has meaning to us because it gives us an emotion of delight.

Why would the sunset give us an emotion of delight. Perhaps such experiences are of either general or particular evolutionary benefit.

As described in the Wikipedia article Evolutionary Aesthetics - "Evolutionary aesthetics refers to evolutionary psychology theories in which the basic aesthetic preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success. Based on this theory, things like colour preference, preferred mate body ratios, shapes, emotional ties with objects, and many other aspects of the aesthetic experience can be explained with reference to human evolution"

IE, perhaps some things have emotional meaning because they offer either general or particular evolutionary benefit. Perhaps they offer an evolutionary aesthetic. -

COP26 in GlasgowComment by Professor Donald Clark:

COP coming to Glasgow. Leaders staying at Gleneagles Hotel & 20 Tesla cars (£100K each) bought to ferry them 75km back & forth. Gleneagles has 1 Tesla charging station, so Malcolm Plant Hire contracted to supply Diesel Generators to recharge Tesla’s overnight. Couldn't make it up. -

The definition of artWe can reduce life to moments of consciousness, and then what we are conscious of are the things we are interacting with — Pop

An important element of phenomenology that Husserl borrowed from Brentano is intentionality (often described as "aboutness"), the notion that consciousness is always consciousness of something. It is rooted in Brentano's intentionality, in that reality cannot be grasped directly because it is available through perceptions of reality that are representations of it in the mind. Thoughts, such as beliefs, are directed towards objects, ie, a thought doesn't exist alone.

(n) The problem is how to escape from the circularity. On the one hand, I am conscious of something (an apple) and I interact with it. On the other hand, I interact with something (an apple) and become conscious because of it.

Could Landauer's principle explain it? — Pop

Landauer's principle can be understood to be a simple logical consequence of the second law of thermodynamics. The second law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of isolated systems left to spontaneous evolution cannot decrease. Entropy is defined as a measure of randomness or disorder of a system.

(n) I see no connection between the randomness or disorder of a system and any consciousness resulting from such randomness or disorder.

interaction with them, is probabilistic — Pop

Interaction can be thought of in two ways. At a large scale the classical interaction between two billiard balls, and at a small scale the quantum interactions between elemental particles.

If the game of snooker is considered at the small scale, the theory is that an electron for example can have a non-zero probability of being in more than one distinct state, which is the definition of a superposition state, such that particles don’t have classical properties like “position” or “momentum”, but have a wave function, whose square gives us a probability of position or momentum. Defining "interaction" as that at the small scale, then the current theory does say that behaviour is probabilistic, in that quantum mechanics is non-deterministic because of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

(n) Yes, at a large scale, the system may be static, but at a small scale, the system is dynamic. But I see no connection between a dynamic system and any consciousness resulting from such dynamism.

So an interaction ( resonance )? Sounds like Enactivism to me? — Pop

It does. A quick internet search found an article within the National Library of Medicine by Ryan & Gallagher titled Between Ecological Psychology and Enactivism: Is There Resonance? In their abstract they write "Ecological psychologists and enactivists agree that the best explanation for a large share of cognition is non-representational in kind" and end with "We conclude with future considerations on research regarding the brain as a resonant organ"

(y) Yes, interaction, resonance and enactivism seem important aspects in explaining how the brain functions. -

The definition of artart being a subjective experience of an aesthetic...............This seems very prescriptive — Tom Storm

I think "art being a subjective experience" is uncontroversial. The question is, what kind of subjective experience. There are many possibilities - beauty, emotion, aesthetic, the expression of will, a mimetic, social comment, etc. However, my personal choice is "the aesthetic", but this is more my definition than a rule.

And does this mean that art can be any object which causes a mind to resonate aesthetically? — Tom Storm

Yes, it seems so to me. Art can be a novel by Cormac McCarthy, a song by Sade, the film Shooter, the design of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Pyramids, the 1989 Mercedes-Benz 300SL R107, a prawn, chilli and lemon tagliatelle, Einstein's concept of spacetime, etc.

As every object has a temperature, every object is an artwork and has an aesthetic. But that is when quality comes into the equation. -

The definition of artit is not art that we speak of but our consciousness of art — Pop

(y) Agree, of the three main epistemological approaches, Idealism, Indirect Realism and Direct Realism, I tend to Indirect Realism. In Indirect Realism, the external world exists independently of the mind, and we perceive the external world indirectly, via sense data. Our subjective experience is private, and even if the object remains the same, our subjective experience may change.

it is important to have definitions that we agree on — Pop

(y) Yes. It has been said that "definitions are not all that helpful". Accepting that language with definitions is difficult, language without definitions would be unworkable

If information is understood as evolutionary interaction — Pop

(n) We have a different definition of "information". I believe that you define it as the dynamic moment of interaction, whereas I define it as the static moment, whether between interactions or at the moment of interaction. For example, I would define "agcactctcacttctggccagggaacgtggaaggcgca" as information"

deterministic with a slight element of randomness — Pop

(n) A deterministic system cannot be random, unless one brings in free-will

Therefore interaction = information — Pop

(n) Considering the system "snooker game", there are periods when the snooker balls interact and there are periods when there are no interactions between the snooker balls. Therefore, in this particular system, not everything is an interaction.

yes beauty is in the eye of the beholder — Pop

(y) Until the eighteenth century, most philosophical accounts of beauty treated it as an objective quality. Augustine in De Veritate Religione asks explicitly whether things are beautiful because they give delight, or whether they give delight because they are beautiful. He emphatically opts for the second.

Even on the Forum, some still argue that "The observer only uses the act of perception over beauty, but the beauty is still there, regardless of the observer"

Though I'm with Kant, who wrote in The Critique of Judgement -

"The judgment of taste is therefore not a judgment of cognition, and is consequently not logical but aesthetical, by which we understand that whose determining ground can be no other than subjective. Every reference of representations, even that of sensations, may be objective (and then it signifies the real [element] of an empirical representation), save only the reference to the feeling of pleasure and pain, by which nothing in the object is signified, but through which there is a feeling in the subject as it is affected by the representation".

The difference is that, whilst beauty is also information, beauty is something the system experiences, whilst information is something the system interacts with and is created from. — Pop

The link between what the system experiences and what the system interacts with

David Hume in Moral and Political 1742 wrote "Beauty in things exists merely in the mind which contemplates them.". Is beauty in the thing independent of the observer, or as Hume wrote, in the mind of the observer ?

My strong belief is that there is a direct informative analogy between the observation of an object such as Window at Tangiers by Matisse and a resulting subjective aesthetic experience, and the ability of an opera singer to use their voice alone to shatter a wine glass.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oc27GxSD_bI

The wine glass shatters. Is it the pitch of the voice that causes the glass to shatter, or is it the shape of the glass that cause the glass to shatter ? It is in fact neither alone, but a resonance between the two, an interaction between the two. In order for the glass to shatter, the voice has to be of one particular pitch and the glass has to be of one particular shape. Resonance is an example of a deterministic cause and effect.

The experience of art requires both a particular artwork and a particular observer, not an artwork alone in the absence of an observer, and not an observer alone in the absence of an artwork. So where is beauty. Beauty cannot exist in an object in the absence of an observer, and beauty cannot exist in an observer in the absence of an artwork. Beauty is a "resonance" between the observer and the artwork.

IE, art happens, art being a subjective experience of an aesthetic, when an observer having a particular state of mind resonates with a particular objective fact in the world. -

The definition of artat the moment of interaction the wave function collapses giving rise to consciousness ?................Basically yes — Pop

Koch wrote "By postulating that consciousness is a fundamental feature of the universe, rather than emerging out of simpler elements, integrated information theory is an elaborate version of panpsychism"

Meaning of "integrated"

On observing a system, such as "an apple on the table" my consciousness about "an apple on the table" is integrated. IE, in that a conscious experience is unified and irreducible, in that seeing a blue book is not reducible to seeing a book without the colour blue, plus the colour blue without the book.

Meaning of "information"

Consciousness is specific. Each experience is composed of a specific set of phenomenal distinctions, a blue colour as opposed to no blue colour, no bird as opposed to a bird.

My consciousness is expressed by my "neural state"

a) On observing a system, for example, "an apple on the table", I am conscious of the information contained within the state "an apple on the table".

b) Suppose the system changes

c) On observing the new system, "no apple on the table", I am conscious of the new information contained within the state "no apple on the table".

In @Pop's terms:

1) "information causes a change in neural state"

2) "information is not something static, but something dynamic"

3) "information is the interaction of physical form"

In my terms:

1) The change in information causes a change in neural state.

2) Information is static, a change in information is dynamic.

3) As regards "information", the observer of the system is conscious of information about the system. As regards "interact", the physical form of the observed system interacts with the physical form of the brain's neural state - as a cue ball interacts with a snooker cue - a matter of deterministic cause and effect.

The problem of information as fundamental

Taken from John Searle's criticism of Tononi and Koch explanation of Integrated Information Theory

"We cannot use information theory to explain consciousness because the information in question is only information relative to a consciousness. Either the information is carried by a conscious experience of some agent (my thought that Obama is president, for example) or in a non-conscious system the information is observer-relative - a conscious agent attributes information to some non-conscious system (as I attribute information to my computer, for example)"

"Koch and Tononi wrote that "the photo-diode's consciousness has a certain quality to it", but the information in the photo-diode is only relative to a conscious observer who knows what it does. The photodiode by itself knows nothing. The information is all in the eye of the beholder"

Art, aesthetics and information

The observer may have information about a piece of art - painted by Andre Derain, dated 1905, titled The Drying Sails, sized 82 × 101 cm.

The observer must be conscious of the artwork in order to know information about it.

The observer has a subjective aesthetic experience when an artwork having a particular physical form interacts with a particular neural brain state - as a cue ball interacts with a snooker cue - a matter of deterministic cause and effect.

IE, as "beauty is in the eye of the beholder", then "information is all in the eye of the beholder". -

The definition of artSentient life is estimated to have evolved on Earth during the Cambrian period about 541 mya to 485 mya. The start of the Universe is estimated at about 13.8 billion years ago. Before sentient life evolved on Earth, physical objects changed with time - lava flowed down the sides of volcanos, rocks bounced down the sides of mountains, etc.

Is it valid to say that the interaction itself is information ?........Yes it is absolutely valid. You have posed a reformulation of Schrodinger's cat problem, which cannot be known until the box is opened. The wavefunction is probabilistic / potential information, when interacted with it's potential is collapsed to a point, which gives rise to a moment of clarity - which is consciousness — Pop

Does this mean that prior to the evolution of sentient life on Earth, if two rocks (or pebbles, atoms, elemental particles) hit each other, ie, interacted, then at the moment of interaction the wave function collapses giving rise to consciousness ? -

The definition of artI know what you mean, and I don't want to unnecessarily quibble about words, but the choice of word does have an effect.

but what is the source of self organization? — Pop

Yes, where is Force X ?

The problem of strong emergence would be reduced to that of weak emergence if we could discover the missing force acting on the neurons.

If we understand these interactions as information — Pop

In snooker, a cue ball hits a coloured ball at rest. I can describe the system before the interaction by knowing information about the position of interaction, initial cue ball speed and direction. I can describe the system after the interaction by knowing the information about the final cue ball speed and direction, coloured ball speed and direction.

There is information about the system before the interaction, and there is information about the system after the interaction.

Is it valid to say that the interaction itself is information ?

The sand dune can be described as a system, and the wind another system, and through interaction they self organize to a form. — Pop

Organising

1) I can organise books on a shelf - the books don't self organise.

2) A computer can organise numbers into increasing size - the numbers don't self-organise.

1) The snooker cue doesn't organise the final resting position of the snooker balls - the final resting position is a consequence of deterministic cause and effect.

2) The wind doesn't organise the final form of the particles of sand - the final form of the sand dune is a consequence of deterministic cause and effect.

3) Force X doesn't organise the final form of the neurons - the final form of consciousness is a consequence of deterministic cause and effect.

IE, organisation requires a rational process, whether that of a conscious person or that of a non-conscious computer, rather than be a consequence of a deteministic cause and effect

Self-organising

At the start of a game of snooker, a snooker cue hits a cue ball which hits a coloured ball, and eventually the snooker balls come to rest.

1) Is it valid to say that the snooker balls interacting with the applied force of the snooker cue have self-organised themselves into their final resting position ?

2) Is it valid to say that the particles of sand interacting with the applied force of the wind have self-organised themselves into their final sand-dune form ?

3) Is it valid to say that the neurons interacting with unknown "Force X" have self-organised themselves into their final conscious form ?

Conclusion

Once conscious, the conscious mind can then organise - books on a shelf etc

But, as consciousness is the consequence of deterministic cause and effect of Force X on neurons, consciousness cannot be the determinant in organising the final form of the neurons when interacting with Force X -

The definition of artemergent understanding — Pop

As you mentioned consciousness and emergence, I wonder if the sand dune analogy gives any insights.

If the observer is aware of the particles of sand, force of the wind on them and the resultant form of the sand dunes, they would explain the shape of the sand dunes as an example of "weak emergence". But, if the observer was only aware of the particles of sand and the resultant form of the sand dunes, they would explain the resultant shape of the sand dunes as an example of "strong emergence".

Following the analogy, the particles of sand are the neurons of the brain, and the resultant form of the sand dune is the mind/consciousness.

In practice, we observe a strong emergence of the mind/consciousness from the neurons of the brain. Perhaps we are missing a force acting on the neurons of the brain of which we are presently unaware. If we could discover this missing force, the mystical problem of strong emergence would become an understandable problem of weak emergence.

The obvious answer would be quantum entanglement, but I feel that most discussion about consciousness uses quantum mechanics either as obfuscation or obscurantism. -

The definition of artIt depends on what you understand information to be — Pop

Although slightly digressing, the following is relevant to "The Definition of Art".

As @Mark Nyquist noted, something that may be overlooked is the definition of the word definition.

On the one hand @Banno wrote "definitions are not all that helpful", but on the other hand

writes about InPhO that "the potential is extraordinary". Yet InPhO is founded on the definition. Barry Smith in the video How to Build an Ontology says that the three steps are 1) you create an ontology which in the simplest possible terms is a controlled vocabulary of labels, 2) you provide logical definitions for those labels so that you can compute using the labels and 3) and then you tag the data using those terms typically you tag the data with URI's addresses

Without definitions, communication would be impossible. If I asked someone to pass me the salt, and they did not know the meaning of salt, rather than tell them to read Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky, a more useful approach would be to say that salt is a white crystalline substance that gives seawater its characteristic taste and is used for seasoning or preserving food.

It is true as you say that "It depends on what you understand information to be", in that sometimes the same word can mean different things to different people, but without the "principle of charity" communication would become impossible.

Perhaps the reader should treat the writer's words and phrases more like idiomatic expressions than literal descriptions. Often a phrase has a meaning independent of the words used, as "in my job interview I had to jump through hoops", where neither jumping nor hoops were involved.

I fully accept the concept behind Kant's "synthetic a priori", though disagree with the word synthetic being used in combination with the word a priori, in that I have decided to treat synthetic a priori more as an idiomatic expression that a literal description. Similarly with "I have understood information to be equal to interaction" and "I am an evolving process of self organisation". As idiomatic expressions I fully agree with them, even if I may have a different opinion as to the particular choice of words, ie, information and self organisation. -

The definition of artIn short it makes no sense to think of an organism absent of it's environment — Pop

(y) Totally agree.

This seems similar to Kant's concept of the "synthetic a priori". Kant wrote in Critique of Pure Reason - "The objects we intuit in space and time are appearances, not objects that exist independently of our intuition (things in themselves). This is also true of the mental states we intuit in introspection; in “inner sense” (introspective awareness of my inner states) I intuit only how I appear to myself, not how I am “in myself”. (A37–8, A42)

This approach also seems similar to evolutionary aesthetics and ethics, where the basic aesthetic and ethical preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success. A topic initiated by Charles Darwin's The Descent of Man and developed by Herbert Spencer.

Enactivism and the analogy of the sand dune

A particle of sand is subject to forces from other sand particles and the wind, meaning that the dynamic interaction between the sand particles and wind brings about the formation of sand dunes. The sand dune evolves because of an dynamic interaction between the particles of sand and their windy environment. The sand dune cannot be understood absent from its environment. The movement of any particular particle of sand is determined by the forces acting on it from surrounding particles of sand and the wind, a deterministic cause and effect. The particles are organised into sand dunes by the physical nature of each particle and the wind acting on them.

IE, the particles of sand may be thought of as the brain's neurons, and the the sand dune may be thought of as the conscious mind. As enactivism proposes that the mind/consciousness has arisen from a dynamic interaction between the neurons of the brain and its environment, we could also say that enactivism also proposes that the sand dune has arisen from a dynamic interaction between the particles of sand and its windy environment.

Information about a thing is an extrinsic property of the thing

The evolution of a sand dune is driven by a complex set of wind forces on a complex set of particles of sand. A single mass may be expressed in terms of information, weight, location, etc. A single force can be expressed in terms of information, direction, strength etc, but such information is an extrinsic property of the force rather than an intrinsic property. Therefore, any effect of the force is not determined by any information that can be expressed of the force. Therefore, the evolution of the sand dune is determined by the forces and particles of sand, not by any information that may be expressed of the forces or of the particles of sand.

IE, evolution cannot be driven by information -

The definition of art(y)An artwork is an object produced with the intention of giving it the capacity (for some person somewhere, at some time) to satisfy the aesthetic interest. — Tom Storm

-

The definition of artThen the art interacts with an observer, and as you point out, this is an inextricable interaction of a consciousness acting upon the artwork and in turn artwork acting upon the consciousness of the observer. It makes no sense to try to separate this interaction in enactivism. — Pop

The word "interact" seems problematic.

Someone observes an artwork, the person becomes conscious of the artwork and the artwork becomes part of the person's consciousness. How can the person consciously interact with the artwork when the artwork is now already part of the person's consciousness. It is not as if one part of the person's consciousness is being conscious of another part of the same person's consciousness.

IE, how can consciousness interact with itself. -

The definition of artLots of questions.

Are you someone who thinks art has a responsibility? — Tom Storm

No. Neither Derain nor Derain's La Rivière bear any responsibility, no more than an apple sitting on a table bears any responsibility. Though the Derain provides an opportunity.

What the Derain does give is a glimpse that there is something deeper and more profound than what is seen on the superficial surface of shapes and colours, of a figure walking past a house next to a river. The painting achieves this using an aesthetic form of pictographic content. What is hidden is not explained, but what is explained is that there is something hidden.

The aesthetic of art is what separates an airport novel from a Hemingway. Superficially,The Old Man and the Sea is a simple story of Santiago, an ageing experienced fisherman, but concealed beneath the words is a complex allegorical commentary on all his previous works.

We are muggles innocently walking along Diagon Alley, unaware of a hidden and mysterious and magical world just out of our reach, hidden by many powerful spells of concealment, seemingly lacking a key. But with art we do have the key. The key is our innate a priori ability to experience aesthetic form, an ability to discover pattern in seeming chaos, enabling the search and discovery of new understanding and knowledge.

Does your perspective risk a subjectivist aesthetic? — Tom Storm

I have the subjective experiences of seeing the colour red, hearing a grating noise, tasting something bitter, smelling something acrid, perceiving aesthetic form. These are not risks to my perspective, these are what I am.

Modernist (capital M) work like Braque's Cubism has an aesthetic too, but is it beautiful? Cannot something which is 'ugly" (however you define this) not also provide a profound aesthetic experience? — Tom Storm

Exactly. Aesthetic is used as an adjective and as a noun.

Aesthetic as an adjective is the study of beauty.

But beauty as a noun surely has a different meaning to aesthetic as a noun. For example, taking the examples of Picasso's Guernica 1937, a moving and powerful anti-war painting, and Bouguereau's 1873 Nymphs and Satyr, mythological themes emphasising the female human body

Dictionary definitions generally agree that aesthetic as a noun means a set of principles governing the idea of beauty, such as "modernist aesthetics" and beauty as a noun means qualities such as shape, colour, sound in a person or thing that gives pleasure to the senses.

Both the Picasso and Bouguereau are important paintings and have aesthetic values. Whilst the Bouguereau may be said to give pleasure to the senses, the Picasso certainly doesn't.

IE, it follows that the aesthetic must be more than being concerned with beauty.

how does one go about identifying what counts as the aesthetic and what does not? — Tom Storm

There are numerous definitions of the aesthetic, from non-utilitarian pleasure to truth. Articles about aesthetics generally conflate aesthetic with beauty. As an aesthetic object can be ugly, the aesthetic and beauty are two different concepts. Therefore, looking at the Wikipedia article on aesthetics, for example, and removing any conflation between aesthetic and with beauty one is left with the following text:

It examines aesthetic values often expressed through judgments of taste

The word aesthetic is derived from the Greek, pertaining to sense perception.

In practice, aesthetic judgement refers to the sensory contemplation or appreciation of an object (not necessarily a work of art)

Judgments of aesthetic value rely on the ability to discriminate at a sensory level.

Aesthetic judgments may be linked to emotions or, like emotions, partially embodied in physical reactions

.It is said, for example, that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".

It may be possible to reconcile these intuitions by affirming that it depends both on the objective features of the beautiful thing and the subjective response of the observer.

Classical conceptions emphasize the objective side of beauty by defining it in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.

Aesthetic considerations such as symmetry and simplicity are used in areas of philosophy, such as ethics and theoretical physics and cosmology to define truth, outside of empirical considerations

Summarising the above - when observing a particular object in the world using the senses of sight, hearing, etc, and experiencing a particular subjective emotion or feeling brought on by a judgement that the parts of the object are combined in the right proportion to make a harmonious whole, then this is the aesthetic. In my terms, the aesthetic is a discovered unity within an observed variety.

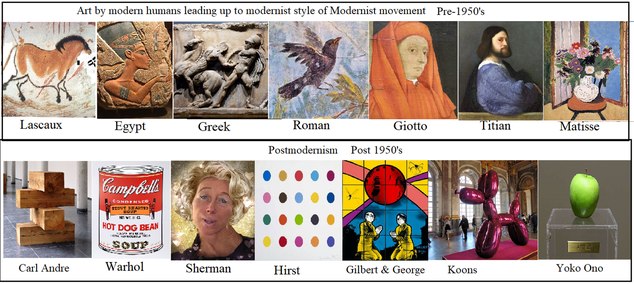

Is all post-modern art free of aesthetic merit ? — Tom Storm

Postmodernism included art, beauty and aesthetics in their attack on contemporary society and culture. As yet, there is no unified postmodern aesthetic, but remain disparate agendas, as discussed in Hal Foster's The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture.

As every object has a temperature, but not to the same degree, every object is an artwork, has beauty and has an aesthetic, but also not to the same degree. Even though Monet's Waterlily and a train timetable have an aesthetic, a Monet Waterlily has a greater aesthetic merit than a train timetable.

As the postmodernists have no agreed definition of the aesthetic, it is difficult to say whether or not postmodernism has an aesthetic of merit.

As regards my understanding of the modernist concept of the aesthetic - a discovered unity within an observed variety - postmodernism is free of modernist aesthetic merit, mainly because it has been a deliberate act on the part of the postmodernists to remove any modernist aesthetic.

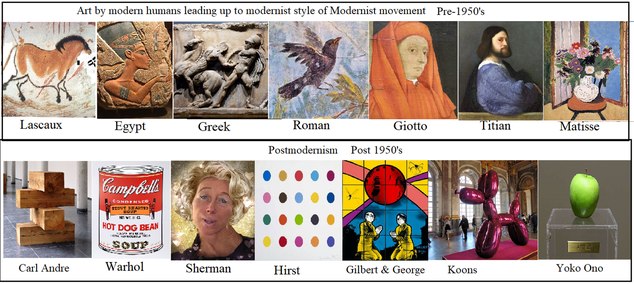

Can you clarify how you would apply your modernist perspective to pre-modern era work? Say a Titian. — Tom Storm

Sentient life is thought to have started during the Cambrian Period, 541 mya to 485 mya and modern humans evolved from archaic humans 200,000 to 150,000 years ago.

It seems clear to me that the pre-1950 examples of art have features in common, and these features are different to the post 1950's examples. In fact, the pre 1950's examples could have been created by the same artist. As regards representation, pre 1950's is pictographic and post 1950's is symbolic. As regards aesthetic form, pre 1950's exhibit a distinct aesthetic quality whilst post 1950's minimise aesthetic quality.

The modernist style of the Modernist movement goes back to at least to the Lascaux cave paintings, painted by modern humans about 20,000 years ago. IE, the modernist style is not new, but is a feature of modern human art. -

Language and OntologyFrege.......Santa Claus and psychologism, — Shawn

Adding background for my own benefit.

Psychologism and anti-psychologism

Frege, founder of logicism, attacked psychologism in his book The Foundations of Arithmetic

Psychologism is where psychology plays a central role in explaining some non-psychological fact in the world and where the observer interprets events in the world in subjective terms. Anti-psychologism, aka logical realism, is the position that the nature of logical truth does not depend on the contents of human ideas but exists independently of human ideas

It seems that psychologism is similar to David Dummett's Anti-Realism, where external reality is hypothetical and is not assumed and the truth of a statement rests on internal logic. Anti-psychologism seems similar to Realism, the truth of a statement rests on its correspondence to an external independent reality independent of beliefs.

It also seems that Frege's anti-psychologism requires that relations have an ontological existence in the world, in that tables, apples, mountains exist independently of any observer.

Internal and external relations

There is a distinction between internal relations and external relations. Internal relations are necessary in that the properties of a thing are essential to the existence of the thing. For example, a table composed of parts, a table top and legs. If the parts were removed then the table would cease to exist. External relations are contingent, in that whether a table is in a garden or in a living room does not affect the existence of the table.

However, FH Bradley argued against external relations using a regress argument, such that either a relation R is nothing to the things a and b it relates, in which case it cannot relate them, or, it is something to them, in which case R must be related to them. In other words, a table top may be above table legs, but where exactly does the relation "above" exist. There is no information in the table top that it is above table legs, there is no information in the table legs that they are below the table top and there is no information in the space between them that there is a table top at one end and table legs at the other.

I see no metaphysical difference between internal relations and external relations. There may be an internal relation between a table and the table top, but at the same time, there is also the external relation between the table top and the table. Wittgenstein discusses something similar in para 59 of Philosophical Investigations - "A name signifies only what is an element of reality. What cannot be destroyed; what remains the same in all changes."—But what is that?....................We see component parts of something composite (of a chair, for instance). We say that the back is part of the chair, but is in turn itself composed of several bits of wood; while a leg is a simple component part. We also see a whole which changes (is destroyed) while its component parts remain unchanged. These are the materials from which we construct that picture of reality"

Frege and Santa Claus

Frege's attack on psychologism seems to me to suggest that Frege supported the idea that relations have an ontological existence in the world. But for me the problem remains, as pointed out by Bradley, exactly where in the world are these relations ? I can appreciate that the parts table top and table legs exist in the world and are spatially separate, but I cannot accept that "above" has an independent existence in the world.

IE, if Frege supported anti-psychologism, it follows that he must have supported the idea that relations have an ontological existence in the world. Therefore, not only must he have believed that the parts of Santa Claus have a real existence in the world, plump, white-bearded, red-suited, etc, but also that the relations between these parts have a real existence in the world, meaning that a Santa Claus consisting of real relationship between real parts must have a real existence in the world. -

The definition of artAre you going by an account of aesthetics rooted in modernist theory, or are you just using the terms as you see them apply? — Tom Storm

I am distinguishing between modernism and Modernism, whilst defining modernism as art that includes aesthetic quality.

Some reference material includes aesthetics as part of the definition of Modern Art and some don't. Generally they don't. For example, the Tate UK description of Modernism doesn't mention the aesthetic. The V&A article on "What was Modernism" mentions beauty. The Wikipedia article on Modernism has a small reference to aesthetics.

And yet there is The British Journal of Aesthetics which promotes debate in philosophical aesthetics and the philosophy of art.

However, it seems to me that the aesthetic is the primary dividing line within art as discussed today.

Even though not central to contemporary articles on Modern Art, I would argue that every important artwork pre-1960 had aesthetic quality, from the Lascaux cave paintings, through Egyptian, Greek and Roman art, from medieval religious art to Impressionism.

Whereas, I would also argue that no important Postmodern art since the 1960's has had aesthetic quality, partly due to Postmodernism's deliberate exclusion of any aesthetic.

IE, within modernism are many different approaches, as with postmodernism, but for me the primary dividing line within art is the presence or absence of the aesthetic. -

Language and OntologyThe process of determining their commitment as ontological entities seems important to say as clear as possible, that they are a fiction. — Shawn

The fictional "Santa Claus" has an ontological existence,

The name "Santa Claus" exists within fiction, fiction exists within language, language exists within the physical structure of the brain, the brain exists as part of the world and is not separate to it, meaning that "Santa Claus" does have an ontological existence in the world.

Where "Santa Clause" exists depends on the ontological nature of relations

The question as to whether relations between parts has an ontological existence in the world is not agreed.

Wittgenstein in para 60 of Philosophical Investigations discusses composite objects composed of parts in relation to each other.

The mind is only able to contemplate a fictional character - Santa Claus, unicorns, Bart Simpson, etc - if the mind already has priori knowledge of the real parts that make up the mereological whole. For example, Santa Claus may be a fictional character, but its parts are known a priori as having ontological existences in the world - plump, white-bearded, red-suited, jolly, old, man, Christmas presents, children. IE, the mind cannot invent parts for which it does not already have a priori knowledge.

Either relations don't have an ontological existence in the world or they do.

If they don't, then relations exist only in the mind and not the world. Such that tables, being a relation between a table top and table legs, don't exist in the world but only in the mind. Similarly, Santa Claus, being a relation between plump, white-bearded, etc doesn't exist in the world but only in the mind.

If they do, then not only tables but Santa Claus exists in the world as mereological objects

Admittedly the parts of Santa Claus are physically separated, but then so are the table top and the table legs, which combine to form a table, and so are the broomstick and the brush in Wittgenstein's example, which combine to form a brush. The parts combine into a "simple" whole. And the "simple" whole ontologically exists in the world.

It could be argued that one problem with mereological objects that every possible combination of parts becomes an object, such that my pen and the Eiffel Tower becomes a "peffel". However, it is in the nature of the mind to name only those mereological objects that it finds pragmatically useful, discarding the uselessness of the concept "peffel" for the usefulness of the concept "table". Therefore, human vocabulary is a mirror of those concepts that the human pragmatically requires in order to evolve within the world.

IE, if relations don't have an ontological existence in the world, Santa Claus only exists in the mind. But if relations do have an ontological existence in the world, then Santa Claus exists in the world. -

The definition of artThe information is not so much in the brick, but in the fact that a person who has total freedom to do as they like, chooses to put a brick on a pedestal. — Pop

Perhaps this remains the sticking point, in that I tend to Modernism whilst you may be leaning towards Postmodernism. Both valid as definitions of art, but different.

Within Postmodernism, an artist has total freedom to create whatever object, concept, performance they want for it to be called art.

Whereas in Modernism, regardless of the definition of art, some objects have artistic value and some don't, where someone who makes an object with artistic value is an artist and someone who makes an object lacking artistic value isn't an artist.

IE, personally, I don't agree with the Postmodernist definition of art, because the words art and artist lose all meaning, as everything can be art and everyone can be an artist. -

Language and Ontologywhy is this such a prominent feature of language to posit an ontology for Pegasus or Santa Claus? — Shawn

Perhaps this is what Wittgenstein was talking about in para 58 of Philosophical Investigations, where I think he is saying that a name such as "Santa Claus" is part of the language game, not an ontological part of the world. -

The definition of artYou are highlighting that the observer interprets the artwork entirely in terms of their own consciousness — Pop

(y) Yes, "art work is information about............consciousness".

But the only consciousness I have ever known is my own. I assume there are other consciousnesses out there in the world, but I may be wrong, I will never know. Even if there are consciousnesses out there other than my own, I will never have any consciousness of a consciousness that is not my own.

IE, as art is information about consciousness, and the only consciousness that I know exists is my own, art can only be information about my own consciousness.

information has a chronological progression. It is causal, — Pop

(y) Yes, information flow is chronological.

As regards Postmodernism, there is no information within a brick that gives the viewer information about the state of mind of Carl Andre. As regards Modernism, there is no information within a painting of a sombre scene whether the artist was in a sombre or happy mood when they painted it. -

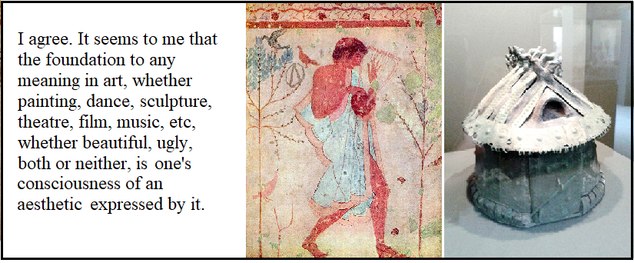

The definition of artSo art expresses the same "self organization" that ordered form in the universe expresses — Pop

The figurine is an object that can be described as art, was made by a consciousness, where consciousness is a result of some kind of self-organisation, can be described as information and expresses something to the observer.

When someone observes information, the information can only express something to the observer if the observer can make sense of the information, can see patterns in the information, in that the information is not chaotic. IE, information by itself cannot express anything to the observer until the observer is able to see patterns in the information.

The patterns the observer is able to see is a function of the observer's mind, the observer's consciousness, and is not a function of whatever caused the figurine to come into existence.

IE, seeing art in the figurine is an expression of the observer's consciousness rather than any history prior to the creation of the figurine.

(y) This doesn't affect the idea that art is information about the conscious self-organising mind, it just moves the mind from the maker of the object to the observer of the object. -

The definition of artwhat can be inferred about the mind activity that made the work, from the work alone — Pop

(y) Anything about art is interesting.

(y) As regards, Integrated Information Theory, I tend to panprotopsychism as an explanation rather than panpsychism.

There is a flow of information - but in what direction ?

I agree that art, especially the aesthetic in art, is a fundamental expression of human consciousness, and art is information, but the question is, in what direction is this information flowing ?

The answer is different for Modernism and Postmodernism

In Modernism, which uses aesthetic form of pictographic representation, as soon as the artist has completed the artwork, the artwork takes on a meaning independent of the artist.

In Postmodernism, which uses symbolic representation, the meaning of the artwork remains tied the artist.

There is a difference between the "maker artist" and the "observer artist"

You write (quote 1) "to explore what can be inferred about the mind activity that made the work" and (quote 2) "you would have to ask the person deeming one object art, and the other one not.....................in an ideal setting we should be able to infer a lot of their mind activity from the clues provided in what they choose as their art".

Quote 1) is about the maker of the artwork as artist. Quote 2) is about the observer of the artwork as artist. Generally writings about art don't make the critical distinction between the person who made the artwork and the person who recognises an object is an artwork. My position is that there is no fundamental, philosophical, metaphysical difference between the "observer artist" and the "maker artist". The person who sees an object and recognises it as an artwork is as much an "artist" as the person who made the artwork. The only differences are practical, in that the "maker artist" has certain skills that the "observer artist" doesn't.

This skill that has taken many years to learn separates the "maker artist" from the "observer artist". The person who appreciates the artistic quality of a Van Gogh has the same artistic appreciation as Van Gogh himself, the difference being that Van Gogh had a profound skill and technical ability in the making of an artwork, whether conscious or instinctual, that most people can never approach.

IE, the difference between an admirer of a Van Gogh and Van Gogh himself is not of artistic sensibilities but of technical skill.

Postmodernism

In Postmodernism, information must flow from the artist that made the artwork to the observer of the artwork, and such information must flow separate to the artwork.

For example, Carl Andre's Bricks, where the meaning of the brick as a symbol cannot be discovered in the symbol itself, but only in the mind of the maker of the artwork.

Modernism

You write "to explore what can be inferred about the mind activity that made the work". I would argue that it is impossible to discover from a Modernist artwork anything about the mind of the maker of the artwork for the following reasons:

1) Some artworks have two or more makers, such as the collaborative work of Ruth Lozner and Kenzie Raulin. To which mind does the artwork have insight into ?

2) Some artworks are ambiguous, such as Monet's St Lazare Station. Is Monet referring to progress in the 20th C or the interplay of light onto physical objects ?

3) Some artworks have no artist makers, only observer artists, for example Warhol's Brillo Box

4) The same artist may paint in completely different styles, such as Van Gogh's early and late period.

5) Different artists may have painted in the same style, such as the Fauves. Vlaminck having a reputation as a loudmouth, troublemaker, and womanizer, whilst Matisse had a conservative appearance and strict bourgeois work habits.

6) The same artist, such as Briton Riviere, may paint a scene of despair Fidelity or of joyful humour Geese

7) Picasso painted Guernica at his home in Paris away from the bombings in Spain, whilst Monet painted Water lilies to the sounds of war.

8) An atheist may paint a religious scene, as Francis Bacon's Crucifixion and the Pope, whilst a religious person may paint a secular scene, such as Caravaggio

9) Interpretation of an artwork is open to debate. Robert Frost's The Road Not Taken is popularly generally taken as a poem about hope, success, and defying the odds, whereas it is in fact the opposite.

10) A contemporary performance of a Mozart piano sonata uses a different type of piano to that used by Mozart, meaning that the modern concert goer is hearing a different sound to that intended by the composer, meaning that a modern performance cannot be expressing what was in the composer's mind.

IE, there is a practical impossibility for the observer to discover links from the artwork into the mind of the artist.

Summary - information cannot flow from the maker of the artwork to the observer via the artwork.

The direction of flow of information is a crucial consideration in art.

In Modernism, which uses aesthetic form of pictographic representation, as soon as the artist has completed the artwork, the artwork takes on a meaning independent of the artist. Information flows between the maker of the artwork and the artwork, between the artwork and the observer of the artwork, but cannot flow from the maker of the artwork to the observer via the artwork.

In Postmodernism, which uses symbolic representation, the meaning of the artwork remains tied to the artist. Information flows between the maker of the artwork and the artwork, and from the maker of the artwork to the observer of the artwork by-passing the artwork entirely, but cannot flow from the maker of the artwork to the observer via the artwork. -

The definition of artBefore it is art, it has to be deemed to be art. — Pop

Suppose a person is conscious of the information arriving through their senses from two objects in the world.

For what reasons would that person deem one object to be art and the other object not art ? -

The definition of artWe now know definitively that all art is information - since information is fundamental. The only question that then remains for art is - information about what? And the obvious answer is consciousness. — Pop

(y) I can see that Integrated Information Theory and Peirce's Theory of Pragmatic Information would be relevant to the meaning of art, and should therefore be considered.

I walk along a path and see a few blown pieces of coloured paper on the ground, making a shape that appeals to me. I pick them up, put them in a frame and hang it on my wall. One year later, happening to visit MoMA, I notice exactly the same image as on my wall, but titled Matisse CutOut. As the two artworks are identical, the artistic quality of the artwork must be independent of whatever created it. I don't care whether the artwork was created by a 20 year old or a 80 year old, was French or Peruvian, had a headache or was worried about paying the rent, in that whatever created the artwork is irrelevant in the recognition of the object as an artwork.

It is true that i) to be conscious is to be conscious of something, ie, intentionality ii) consciousness creatively organises information iii) the observer of the artwork is conscious of receiving information from the artwork, shapes, colours, relationships, etc.

@Pop - i) "art work is information about the artist's consciousness" ii) "art conveys.........the consciousness of the artist" iii) "art's function is to express our consciousness". Summarising, the artwork expresses the consciousness of the artist.

But an actuary table is not art, and a Matisse CutOut is art. Therefore there must be a conscious act of determining what is art and what isn't. If whatever created the object is irrelevant in the recognition of the object as an artwork, and the object itself cannot determine that is an artwork, then the conscious act of determining the object as an artwork must be in the observer.

But the observer only knows that the object is an artwork by recognizing it as an artwork, regardless of the intentions of whatever made the object.

IE, looking at the object as an artwork is an expression of the ability of the observer to recognize an object as an artwork, rather than any expression of the observer's ability to look into the mind of whatever made it. -

The definition of artThey have an information theoretic running through them, which I am in the process of understanding. — Pop

For my own knowledge:

Is Norbert Wiener's 1950 The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society relevant to your position - where art is just a part of patterns of information within the world ?

Also, is the article Dissecting landscape art history with information theory 2020 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America relevant to your position - whose approach at a meta-narrative is that of a quantitative understanding of a landscape painting rather than a qualitative one ? -

The definition of artI think art is to grounded in the aesthetic, and the aesthetic is to be grounded in affect. — Constance

@Constance "Calling an eclair sweet is certainly not a priori"

(y) True. As further described by post-Darwinian "evolutionary aesthetics" and "evolutionary ethics", humans are born with certain innate abilities, in that the brain is not a blank slate. The contemporary word "innate" serves the same purpose as Kant's 18th C word "a priori".

There is a certain ambiguity in the phrase "a priori knowledge". On the one hand it can mean a priori knowledge of the subjective experience of the colour red, sweet taste, aesthetic form, etc. On the other hand it can mean that some people have a genetic predisposition to certain skills and abilities, whether being naturally good at languages, mathematics, people skills, dance, football, etc, where such innate knowledge is not of the goal itself - but an instinctive understanding of how to achieve the goal

IE, it is a priori knowledge of how to achieve a goal rather than a priori knowledge of the goal itself.

@Constance "visual form may elicit the aesthetic...........form itself is not aesthetic"

@Constance "Affect is..............the essential feature of art"

@Constance "I think art is to grounded in the aesthetic, and the aesthetic is to be grounded in affect"

(y) I agree. Clive Bell proposed the concept of "Significant Form", where "There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless" and "lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions".

Commentators write "the origin of the aesthetic emotion is within the object itself", but such explanations are ambiguous. Someone observes an object, and there is something about the particular form of the object that induces an aesthetic experience in the mind of the observer. The thing to note is that the object only has a form that is significant to the observer, not that the object has a significant form that is independent of any observer

IE, "significant Form" exists in the observer, not the object observed.

@Constance "This brings the issue to Wittgenstein and why he refused to talk about ethics and aesthetics"

(y) Wittgenstein wrote in TLP 6.421 "It is clear that ethics cannot be put into words. Ethics is transcendental".

In a sense Wittgenstein refused to talk and ethics and aesthetics, but as Bertrand Russell wrote in the introduction to the Tractatus "Mr. Wittgenstein manages to say a good deal about what cannot be said, thus suggesting to the sceptical reader that possibly there may be some loophole through a hierarchy of languages, or by some other exit".

In a letter to Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein complained that the British philosopher did not understand the main message of theTractatus. He explained that “the main point is the theory of what can be expressed by propositions—i.e., by language . . . and what cannot be expressed by propositions, but only shown; which, I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy”

But in practice, philosophers have made reasonable livings from teaching and writing books about aesthetics and ethics, so it cannot be as clear cut as Wittgenstein suggests.

It is interesting fact that I know for certain that my private subjective experience of the sweet taste of an eclair and aesthetic form are the same as yours, as much as I know that there is a cup of tea on the table in front of me.

So how is it that communication using language is possible, using public words such as sweetness of taste and aesthetic form, where such public words refer to private subjective experiences that can never be described in words.

So how do I know for certain that my private subjective experience of aesthetic form is the same as your private subjective experience of aesthetic form, when the only thing they have in common is the public word "aesthetic form".

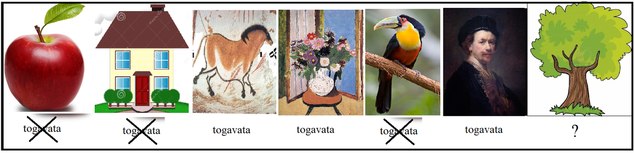

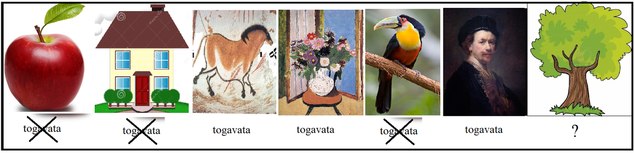

Using only six pictures, I believe the meaning of "togavata" would be generally understood, sufficient to be able to classify the final picture on the far right as either "togavayat" or not "togavata"

IE, I cannot describe my private subjective experience of "togavata", yet I can relatively easily communicate my private subjective experience of "togavata" by attaching a public word to it.

Language is thereby able to communicate private subjective experiences by linking public words to them, thereby allowing language to be used to communicate private subjective experiences, whether aesthetic form, sweetness of taste, the pain of a headache, etc.

IE, Wittgenstein could have sensibly talked about aesthetics and ethics by linking public words to his private experiences of them. -

The definition of artCan you identify a critic or writer who embodies this view — Tom Storm

In particular - Professor Denis Dutton.

In general - "Evolutionary Aesthetics".

Professor Dutton talks about "The Art Instinct" at www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-Di86RqDL4 -

The definition of art(a priori knowledge).. .....This post is not relevant to the discussion — T Clark

Since at least the Lascaux cave paintings 17,000 years ago, beauty and aesthetics have been considered part of the essence of the meaning of art, part of the "definition of art".

Sentient life is born with certain innate "a priori" abilities. We are able to know the subjective experience of the colour red, a bitter taste, an acrid smell, the pain of a headache, as well as aesthetic form. These subjective experiences don't need to be taught in school.

In Western philosophy since the time of Immanuel Kant, such knowledge, acquired independently of any particular experience, has been known as "a priori knowledge".

IE, any discussion of art needs an understanding of aesthetics, which in its turn needs an understanding of "a priori knowledge". -

The definition of art(a priori knowledge)............"You're stretching the meaning of those words to match reality. — T Clark

In a sense I am stretching the meaning of the words a priori and knowledge within the phrase "a priori knowledge".

But in the case of the phrase "a priori knowledge", it is the phrase as a whole that has meaning rather than the particular words within it. It is the same as if I said "In my job interview I had to jump through hoops", where the concept "jump through hoops" is not determined by the particular words jump, through and hoop. Or if a said "Mary is a breath of fresh air" or "John flew off the handle". In the same way, expressions such as "a priori knowledge", "synthetic a priori" and "transcendental idealism" are more idiomatic expressions than literal descriptions. The phrase "a priori knowledge" then becomes a key phrase when used in search engines conveniently leading to more extensive explanations, such as in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy or Wikipedia.

IE, "a priori knowledge" is an idiomatic expression and is only a guide to the concept rather than a literal description of it. -

The definition of artVan Gogh — Pop

(y) If only in real life were there Doctor Henry Black's who were present in art museums explaining to the passing public the importance of the paintings they were looking at. -

The definition of art"art." — T Clark

@T Clark - "There are also definitions that are of very little use" (y)

@T Clark - "Keeping in mind that "aesthetic" actually has an accepted meaning - Concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty"

Not exactly.

Aesthetic as an adjective is the study of beauty.

But beauty as a noun surely has a different meaning to aesthetic as a noun. For example, taking the examples of Picasso's Guernica 1937, a moving and powerful anti-war painting, and Bouguereau's 1873 Nymphs and Satyr, mythological themes emphasising the female human body

Dictionary definitions generally agree that aesthetic as a noun means a set of principles governing the idea of beauty, such as "modernist aesthetics" and beauty as a noun means qualities such as shape, colour, sound in a person or thing that gives pleasure to the senses.

Both the Picasso and Bouguereau are important paintings and have aesthetic values. Whilst the Bouguereau may be said to give pleasure to the senses, the Picasso certainly doesn't.

IE, it follows that the aesthetic must be more than being concerned with beauty

@T Clark - "I've always hated this idea - that we can't explain sight to a blind person"

I know the subjective experience of colours in the visible light spectrum, red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, blue, violet. It seems that reindeer can also see the colour ultraviolet, which is useful to them in spotting lichens that they can eat.

The trick is, can you explain to me in words the subjective experience of the colour ultraviolet !

@T Clark - three cords and the truth. (y)

Exactly. Matisse's Cut-outs are some of my favourite artworks, minimal yet sophisticated.

@T Clark - value may be as much or more important than pattern. (y)

@T Clark - We are born with inborn instincts for certain ways of processing the world, learning about it...................We are born with the equipment to collect sensory input and the processing ability to interpret and use it" (y)

I agree.

I wrote "Humans have a priori knowledge", and I agree that my use of the word "knowledge" may be problematic, but I stick with it

"Knowledge" is defined as "facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject" which seems fair enough.

1) Our inborn instincts could be said to include "facts, information and skills"

2) Our "experience and education" has been acquired through billions of years of evolution rather than the schoolroom.

3) As regards innate "theoretical or practical understanding" of the colour red say, "understanding" may be defined as the capacity to apprehend general relations of particulars and the power to make experience intelligible by applying concepts. Then it must be the case that the brain has the innate capacity to apprehend general relations of particulars and does have the innate power to make experience intelligible.

IE, I stick with the concept of "a priori knowledge" -

The definition of artThe artwork is a mirror of the spirit — Constance

If this were part of the Stanford University undergraduate progam in philosophy, it would be costing me $58,000 a year - so I can't complain at $40 a year.

There is no correct definition of art

The definition "art is a bottle of Guinness" is as correct as any other. Definitions are determined by Institutions and the majority of interested people.

Various definitions of art

@Constance - "Art has this, I say. It is called the aesthetic"

@Constance - "The question of art lies with one question: is there anything that is both the essence of art, what makes art, art, and absolute?"

My personal definition of visual art is aesthetic form of pictographic representation

Definitions of the aesthetic

@Constance - "As to Beauty, I don't think, frankly, Hutcheson has a clue"

I would define the aesthetic as unity in variety, along the lines of Hucheson. Hucheson is giving an objective definition of the aesthetic, not attempting to describe the subjective experience.

I can describe objective facts about the colour red - seen in strawberries, sunsets, etc, has a wavelength of 625 to 700nm. I can also describe objective facts about the aesthetic - unity in variety, observed in a painting by Matisse, a book by Cormac Mccarthy, a song by Sade, etc. But I can never describe the subjective experience of the colour red or the aesthetic to someone who can never experience the colour red or aesthetic. However, I can use language to communicate my subjective experience of the colour red or aesthetic to another person who has also experienced the colour red or aesthetic.

IE, language can communicate general things about subjective experiences but can never communicate the particular subjective experience.

Aesthetics has value of two kinds

@Constance - " in aesthetics and ethics, there is value. Value is non cognitive"

The aesthetic can have two kinds of value, and these two meanings of value are independent of each other.

1) Value as the regard that something is held to deserve, the judgement of good or bad, in that the aesthetic of a Rembrandt is better than the aesthetic of a child's crayon sketch.

2) Value as a numerical measure, magnitude, quantity. Note that aesthetic value is not binary. It is not the case that an object either has an aesthetic or doesn't. As every object has a temperature , objects may have different temperatures. As every object has an aesthetic, different objects may have a different degree of aesthetic value.

Judgement of value as regards good or bad

The good of the aesthetic may exist in either the observer or the world.

@Constance "Wittgenstein thought that Good was divinity, and I think this problematically right"

My belief is that the source of the Good is human pragmatism

1) As regards the observer, the judgement of the Good certainly exists in the observer

2) As regards the world, the question as to whether morality exists in the world independent of any observer is open to debate. Moral realism says that morality does actually exist, and it exists in a knowable, universal way. Moral subjectivism claims that morality is not real or universal, and it does not exist outside the mind.

Judgement of value as regards degree

The degree of aesthetic may exist in either the observer or the world

1) As regards the observer, the judgment of degree certainly exists in the observer.

2) As regards the world, if the aesthetic is unity in variety, meaning a particular relationship of parts to the whole, the question as to whether relations ontologically exist in the world or merely attributions made by conscious entities and expressed in language is open to debate.

Evolution explains why we have the aesthetic

@Constance - "Evolution has always been uninformative, anyway, for it could never explain meaning, aesthetic, ethical"

@Constance "Evolution, at this level, says nothing"

In the world is chaos. Sentient life is able to survive and evolve by its innate and intellectual ability to discover patterns within this seeming chaos, ie, by discovering unity in variety. In other words, humans have an aesthetic sensibility. Evolution does not explain what the aesthetic is, but evolution does explain why the aesthetic originated in sentient life.

The brain has evolved in the world to be able to survive within the world.

Human a priori knowledge is that knowledge necessary to survive in the particular world we find ourselves in. It would follow that a sentient life evolving in a different world, whether hotter, silicon based or higher gravity, would have different a priori knowledge suitable for that different world. Rorty and the neo-pragmatists accept a mind-independent reality, whilst maintaining that this world can never be knowable. The human develops beliefs and habits which allow them to adapt to their environment with success. If humans had no a priori knowledge we would be back at Hume's problem of inference regarding the observation of a constant conjunction of events. This is the problem Kant attempted to solve with his concept of the synthetic a priori.

IE, the truth is a matter of perspective. Rather than as the neo-pragmatists propose, humans can only make sense of the world by applying reason to what they observer through their senses, it is more the case that sentient life, not separate to the world but as a part of it, have evolved innate a priori knowledge of the world. Such a priori knowledge allows them an understanding of the world even before experiencing it through their senses.

Our conscious mind has transcendent connection with the world bypassing the senses

@Constance - "Art may be an open concept, utterly, but it is grounded in the pragmatic authority of our times"

@Constance - "for to speak of a world of which we are a part is to speak of something not witnessable"

@Constance - "Rorty and others deny that knowledge can in any way align with "reality" at the foundational level"

@Constance - "The real issue lies in meta-aesthetics/ethics: what is the Good?.............The understanding is pragmatic, I claim, which is why the aesthetic cannot be spoken"

Sentient life, including humans, are born with certain innate knowledge - such as the colour red, bitter tastes, acrid smells, what is hot to the touch, the pain of a headache, as well as the aesthetic. In line with Kant's view, a priori intuitions and concepts provide a priori knowledge, which also provides the framework for a posteriori knowledge. This a priori knowledge does not need to be taught, in that the brain is not a blank slate when born. IE, children don't need to go to school to learn how to have the subjective experience of the colour red.

But this is particular knowledge, in that I am not able to imagine an bitter taste independent of experiencing through my senses an object in the world that gives me the subjective experience of a bitter taste. This a priori knowledge is about the possibility of being able to experience a particular subjective experience, not the subjective experience itself. The point is that this a priori knowledge of the possibility of experiencing a particular subjective experience exists in the brain prior to any observation of the world through the senses.

IE we have a priori knowledge of certain subjective experiences prior to ever experiencing them through our senses, in that we can speak of a world which we have not witnessed.

Summary

Art is important because it is aesthetic form of representative content. The aesthetic is important because it is an innate foundational ability of sentient life to discover patterns in a seemingly chaotic world. Art is therefore an outward expression of the innate character of the brain and conscious mind. -

The definition of artfor Rorty, this world is "made, not discovered" — Constance

Sentient life is not just an observer of the world but is a part of the world

The human observer does not lead an existence separate to the world. The human is an integral part of the world, and has been part of an evolutionary process stretching back at least 3.7 billion years - a synergy between all parts of the physical world, of matter and force, between nature and life.

IE, the human is not an outside observer of the world, but part of the world.

The pragmatist view is only half the story

The pragmatist holds the position that the purpose of our beliefs as expressed in language is not to understand the true nature of reality existing on the other side of our senses, but to succeed in whatever environment we happen to find ourselves. As with Kant's synthetic a priori, we make sense of the world by imposing our a priori concepts onto the world we observe

However, the human observer does not have a separate existence to the reality of any world external to their senses, but is an intrinsic part of reality. The observer is part of the world and the world is part of the observer, they are one and the same.

As the observer is part of reality, then any beliefs the observer has about the reality of logic, aesthetics, ethics, space, time, etc must also be an inherent part of reality itself.

Rather than we make sense of a reality external to our senses by imposing our a priori concepts onto it, part of reality makes sense of itself through a priori concepts.

IE, the pragmatist holds the position that the human observer only has an indirect contact with reality through the senses, whereas in fact, the human observer's knowledge also comes from being in direct contact with reality, being an intimate part of reality.

The question as to whether the aesthetic exists in the object observed the other side of the sense or within the observer disappears, as the reality on the other side of the senses is the very same reality as within the observer, in that there is only one reality. The aesthetic within the world and the aesthetic within the observer are one and the same, as any aesthetic in the sentient life is exactly the same as the aesthetic in the world from which it evolved over billions of years. IE, The word "aesthetic" only exists within human language, which only exists within humans, which exist within the world, meaning that "aesthetics" must exist in a world within which humans exist.

As I see it, the aesthetic is an abstract expression of the human ability to discover pattern in seemingly chaotic situations, to discover uniformity in variety, an invaluable trait in evolutionary survival. As Francis Hutcheson wrote in 1725: “What we call Beautiful in Objects, to speak in the Mathematical Style, seems to be in a compound Ratio of Uniformity and Variety; so that where the Uniformity of Bodys is equal, the Beauty is as the Variety; and where the Variety is equal, the Beauty is as the Uniformity”.

For me, important visual art requires aesthetic form of pictographic representation. As expressed by Hegel, formal quality is the unity or harmony of different elements in which these elements are not just arranged in a regular, symmetrical pattern but are unified organically together with a content of freedom and richness of spirit (though for me not a content of the divine).

Summary

In summary, the pragmatists are making the mistake of not taking into account the fact that because we are in intrinsic part of the world, this world "is also discovered, as well as made". -

The definition of artWhen art is undefined it fragments — Pop

An object can only have value if first defined. An object defined as a ship that sinks on first entering the water can rightly be said to be no good as a ship. The same object defined as a submarine that sinks on first entering the water may rightly be said to be good as a submarine.