Comments

-

Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"AC Grayling: "One need not take as one's target so radical a form of the thesis to show that cognitive relativism is unacceptable, however."

FORMS OF LIFE

As rules are private, a rule-based language must also be private

Suppose there is culture A with its own form of life, its own language, its own rules and its own truth and culture B with its own form of life, its own language, its own rules and its own truth.

The cognitive relativist says that because each culture has its own form of life it has its own truth, meaning that truth is relative between different cultures.

But AC Grayling argues that cognitive relativism is unacceptable, because its premise that there are different cultures each with its own form of life is an implicit acceptance of the fact that we can only recognize that cultures are different only if we understand what these differences are. If we understand these differences, then there is a common ground between different cultures, thereby negating the concept of cognitive relativism.

But cultures aren't Platonic entities, they are sets of individuals, whether one considers a single individual on a desert island or 6 billion individuals on planet Earth.

Each individual is an individual, receiving information about a world outside them through their five senses.

Knowledge is justified true belief.

The individual may have beliefs about a world existing outside them causing their perceptions, and may be able to justify their beliefs using logical reasoning, but cannot be said to have knowledge about any world existing outside them. Although the individual may be able to justify their beliefs about any outside world, they can never prove such beliefs.

For an individual, all the rules that they are aware of must be of their own invention, even if based on information received through their senses. As the tortoise said to Achilles, how can an individual discover just from the information received through their senses that a rule is a rule. Where is the rule that determines whether something is a rule or not, a problem of infinite regression.

As regards language, the individual perceives shapes, which are words, which are part of language, but as the rules of language cannot be included within the shapes themselves, the rules of language that the individual uses must have been created by the individual themselves. If language is rule-based, and these rules are private, then language must also be private, and must be a "private language".

An individual only gets information about any world outside them through their senses. There may or may not be different cultures in this world outside them. Dependent on what information the individual gets through their senses, some of these different cultures they may know about, and some they don't know about.

For those different cultures the individual is aware of, the individual creates the rules of that culture. The individual doesn't discover the rules of that culture in the information coming through their senses. As the form of life of a culture is dependent on the rules of that culture, the individual also creates the form of life of that culture. Therefore, if an individual is aware of different cultures, then not only has the individual created the rules of those cultures, but has also created the forms of life of those cultures. Of necessity, there is now common ground between these different cultures, and these cultures are not closed to each other. As Grayling says, the concept of cognitive relativism is negated. The important thing to note is that cognitive relativism is referring to the cognitive state of the individual who is aware of different cultures, not the cognitive states within these different cultures.

However, for those cultures the individual doesn't know about, the individual has no knowledge of either the rules or the forms of life of those unknown cultures. If the individual doesn't know about such cultures, they are obviously not able to recognize a different form of life. In this case, Grayling's assertion that cognitive relativism is unacceptable is clearly mistaken..

As rules are private, a rule based language and a rule based form of life must also be private. Grayling is correct when he says that cognitive relativism is unacceptable when an individual is able to recognize another form of life, but is turning a blind eye to those situations where the individual is not able to recognize another form of life, because the individual is not aware of them in the first place. An unknown remains an unknown. -

A tough (but solvable) riddle.Hey you got it! — flannel jesus

Not very elegantly, I'm afraid. Thanks for posting the logic problem. -

A tough (but solvable) riddle.So, whose door is White? And what medium does the Kenyan use for his art? — flannel jesus

The Brazilian's door is white. The Kenyan is a photographer. -

Ambiguous Teller RiddleThen I asked yesterday if A was ambiguous or just contradictory. The debate remains. — javi2541997

Suppose Person A says "the Tower Bridge is in London and the Taj Mahal is in Spain".

When he says "the Tower Bridge is in London", we describe them as a "Truth Teller", and when he says "the Taj Mahal is in Spain", we describe them as a "Liar".

Person A can only have two positions, either that of a "Truth Teller" or that of a "Liar", but only at different times, in that he cannot be a "Truth Teller" and "Liar" at the same time.

Similarly, that a train may be in Paris at one moment in time and in Lyon at another moment in time doesn't make the train either contradictory or ambiguous. -

Ambiguous Teller RiddleIs it possible to formulate it using first-order logic? — javi2541997

Person A claims person B always tells the truth.

Person B claims person B (himself) sometimes tells the truth.

Person C claims person B always lies.

Knowing that person A sometimes lies, person B always lies and person C never lies.

Perhaps in order to formulate in First Order logic, one should start with a set of statements, where each statement is either a lie or not a lie, and where the variable x stands for a statement.

∃x (Lie (x) ∨ ¬ Lie (x))

Perhaps one should also try to avoid the problem of Russell's Barber Paradox, where the person is named after their occupation. If someone always barbers, they can be called a "Barber". If someone never barbers, they can be called "Not a Barber". But if someone at one moment barbers and at a later moment doesn't barber, they can neither be called a "Barber" nor "Not a Barber"

Similarly, it seems that a problem with First Order Logic would arise if someone who always lies is called a "Liar" and someone who never lies is called "Not a Liar". Within the logic of First Order Logic, a "Liar" is not "Not a Liar". There is no middle ground to account for person A , who is neither a "Liar" nor "Not a Liar".

Therefore, given a set of statements, some of which are lies and some aren't:

Person A is someone whose statements are sometimes lies and sometimes not lies, not that person A makes every possible statement within the set that is a lie and every possible statement that is not a lie.

Person B is someone whose statements are always lies, not that person B makes every possible stalemate within the set that is a lie

Person C is someone whose statements are never lies, not that person C makes every possible statement within the set that is not a lie

How First Order Logic achieves this is beyond my pay grade. -

Ambiguous Teller RiddleWho is the liar? — javi2541997

I agree with @flannel jesus that A sometimes tells the truth, B always lies and C always tells the truth. (admittedly my solution is more convoluted).

Presumably, a person who always tells the truth is different to a person who sometimes tells the truth, and in this sense are mutually exclusive.

IF A always lies - B always tells the truth - C sometimes tells the truth

THEN B would not say of himself "B sometimes tells the truth"

IF A always lies - B sometimes tells the truth - C always tells the truth

THEN C would not say about B "B always lies"

IF A always tells the truth - B always lies - C sometimes tells the truth

THEN A would not say about B - "B always tells the truth"

IF A always tells the truth - B sometimes tells the truth - C always lies

THEN A would not say about B - "B always tells the truth"

IF A sometimes tells the truth - B always tells the truth - C always lies

THEN B would not say about himself - "B sometimes tells the truth"

The only remaining possibility is - A sometimes tells the truth - B always lies - C always tells the truth.

On the occasion that A was lying rather than telling the truth, A would say one of two things about B, either "B always tells the truth" or "B sometimes tells the truth"

B would say one of two things about himself, either "B always tells the truth" or "B sometimes tells the truth".

C would say of B, "B always lies"

The three statements work on the understanding that A happened to be lying rather than telling the truth. -

Even programs have free willYes, the oracle may perfectly well know that thwarter will do the opposite of what he predicts, but he has committed to his prediction already. It will be too late already. — Tarskian

The Thwarter app has a source code which specifies how the Thwarter app performs a calculation when input information

The Thwarter app is given an input and performs a calculation to arrive at an answer.

It may be that the Oracle app knows that the answer is contained within the input information.

However, the Thwarter app would only know that the answer was contained in the input information after it had completed its calculation, and then it would be too late to change what type of calculation it had used.

IE, the calculation that the Thwarter app uses cannot be determined by an answer that is only known by the Thwarter app after it has completed its calculation. -

Even programs have free willIn fact, there is no app that can tell minute by minute what even any other app will be doing. — Tarskian

Time is of the essence.

The Thwarter app is not aware (figuratively speaking) of the existence of the Oracle app. All the Thwarter app is aware of is input.

Therefore, we only need to consider the Thwarter app.

Feedback occurs when the output of the Thwarter app then becomes new input. This is a temporal process, in that its output happens at a later time than its input.

The source code of the Thwarter app determines the output from the input using the function F, where output = F (input).

For example, if the input is a set of numbers, such as 3, 5 and 7, the output could be the addition of this set of numbers, such as 15.

At time zero, let there be an input I (1). This input cannot include any subsequent output, as any output happens at a later time.

At time t + 1, the output O (1) can be predicted from the function F operating on input I (1).

At time t + 1, the new input I (2) includes output O (1).

At time t + 2, the new output O (2) can be predicted from the function F operating on input I (2).

At time t + 2, the new input I (3) includes output O (2).

Etc.

At each subsequent time, the output can be predicted from the input. The output is pre-determined by the input.

At any time t + x, the output has been pre-determined by the situation at time zero. -

Mathematical truth is not orderly but highly chaoticSo in a way, negative self reference in my opinion is a very essential building block for logic. — ssu

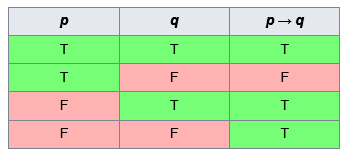

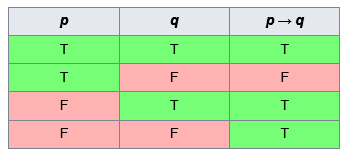

Let p be "I can write anything". Let q be "I know everything".

Consider the statement "If I can write anything then I know everything"

"If I can write anything then I know everything" seems reasonably true.

"If I can write anything then I don't know everything" seems reasonably false.

"If I cannot write anything then I don't know everything" seems reasonable true'.

However, as regards logic using the Truth Tables, "if I cannot write anything then I know everything" is true, regardless of whether it initially seems unreasonable.

In logic, negative expressions are as important as positive expressions, but can lead to strange places. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsUnfortunately, as away for a week, cannot give your post the time it deserves. The question remains, is the Tractarian atomic proposion "Is red (the patch)" or "Is red (x)"?

-

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsWitt clearly is offering this up as an example of an atomic proposition, not a proposition. He starts by saying that he believed that one needed to introduce numbers into atomic propositions, and that he would provide an example of what he means, which was the square example with [6-9, 3-8] R as the elementary proposition: — 013zen

I agree that [6-9, 3-8] R is an atomic proposition, aka elementary proposition.

Referring to Wittgenstein's Some Remarks on Logical Form, as he writes that any given proposition is the logical sum of simpler propositions, eventually arriving at the atomic proposition, this means that an atomic proposition is still a proposition.

He writes "the representation of a patch P by the expression [6-9, 3-8]

The numbers [6-9, 3-8] are introduced to represent the patch, which is the content.

He also writes "a proposition about it, e.g., P is red, by the symbol [6-9, 3-8] R"

So we have the proposition "the patch is red", which may also be written as either "Is red (the patch)" or [6-9, 3-8] R.

As [6-9, 3-8] R is an atomic proposition, then so is "the patch is red".

"Is red (the patch)" has both form and content, whereas "Is red (x)" has form only. The argument x being a variable is a Formal Concept. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsHe goes on to describe how one might analyze the proposition: "The square is red" into the elementary propsition: " [6-9, 3--8] R " — 013zen

If Witt truly thought that "X is red" was an elementary proposition, why would he attempt to construct an analysis into " [6-9, 3--8] R " in Some Remarks on Logical Form? — 013zen

As I understand it, the atomic proposition is of the form - Is red (the patch) - not - Is red (x).

In Wittgenstein's article Some Remarks on Logical Form, I take atomic proposition to be a synonym for elementary proposition.

Wittgenstein writes that "Every proposition has a content and form"

He also writes that any given proposition is the logical sum of simpler propositions, eventually arriving at the atomic proposition. It is in these atomic propositions that contain the material, the subject matter. IE, the content.

As every proposition has content and form, and as any given proposition is the sum of atomic propositions, atomic propositions must also have content and form.

As - Is red (x) - has form but no content, it cannot be an atomic proposition. However, as - Is red (the patch) - has both content and form, it may be an atomic proposition.

Wittgenstein writes that a proposition about the patch can be "P is red"

Wittgenstein represents this patch by [6-9, 3-8]

Therefore the expression - Is red (the patch) - may be replaced by - Is red [6-9, 3-8] - or as he writes [6-9, 3-8] R

Therefore the expression [6-9, 3-8] R is a proposition, and as he says, every proposition has content and form.

Wittgenstein replaces the proposition - Is red (the patch) - by [6-9, 3-8] R - where both are of the form of an atomic proposition. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughts(the colour exclusion problem)...........I've never heard the position that this supposed problem was one of if not the reason why Witt wrote the PI. — 013zen

The colour exclusion problem for the Tractatus

Ramsey's criticisms of the Tractatus is crucial in Wittgenstein's change from his early to late philosophy.

Ramsay argued that Wittgenstein's statement that it is logically impossible that a single point in the visual field can be two colours at the same time was contradictory to his statement that elementary propositions are logically independent, a pillar of the Tractatus, This is known as the colour-exclusion problem.

6.3751 For example, the simultaneous presence of two colours at the same place in the visual field is impossible, in fact logically impossible, since it is ruled out by the logical structure of colour.

4.211 It is a sign of a proposition's being elementary that there can be no elementary proposition contradicting it

It is the properties of space, time and matter that determine the non-logical impossibility that at the same place both the general propositions "this is red" and "this is green" can be true, not the logical necessity of the tautology or the logical impossibility of the contradiction.

On the one hand, the simple colour proposition "this is red" appears to be an elementary proposition because seemingly not a truth-function of other propositions, but on the other hand, the simple colour proposition "this is not green" logically follows from the simple colour proposition "this is red", meaning that such simple colour propositions cannot be independent.

Wittgenstein's abandoning logical atomism was in large part due to Ramsey's pointing out the colour-incompatibility problem in the Tractatus, and turned away from the Tractatus to that of a family resemblance approach in Philosophical Investigations, which does not use the logical necessity of the Tractatus to distinguish meaningful from senseless propositions.

What are elementary propositions.

Note that in Philosophical Grammar, Wittgenstein was treating the expression "this place is now red" as an elementary proposition, not the logical form of the proposition such as F(x) as the elementary proposition.

In addition, elementary propositions assert a states of affairs, where an elementary proposition is an arrangement of names and a state of affairs is an arrangement of objects. An elementary proposition is true or false dependant upon whether a state of affairs obtains or not. It is the case that the elementary proposition has the same logical form as the state of affairs it asserts, not that the elementary proposition is the logical form.

Sraffa’s Impact on Wittgenstein - Matthias Unterhuber, Salzburg, Austria

Ramsey’s criticism (1923) of the Tractatus (Wittgenstein 1922/1933) is essential for the change from Wittgenstein’s earlier to his later philosophy (Jacquette 1998). Ramsey’s influence on Wittgenstein is very easily traceable, as Ramsey (1923) published his criticism of the Tractatus and Wittgenstein modified the approach of the Tractatus to account for the criticism and published his response in Some Remarks on Logical Form (Wittgenstein, 1929). He, however, eventually noticed that his modified approach did not solve the problem suggested by Ramsey.

The criticism of Ramsey amounts to the fact that Wittgenstein could not explain a statement he accepted: that a “point in the visual field cannot be both red and blue” (Ramsey 1923, p. 473). According to the Tractatus “the only necessity is that of tautology, the only impossibility that of contradiction” (p. 473). The present contradiction, however, is attributable rather to properties of space, time and matter and is not accounted for by the general form of proposition which according to the Tractatus determines all and only genuine propositions. Wittgenstein eventually gave up the thesis that there is a general form of proposition and resumed a family resemblance approach which does not provide necessary and sufficient conditions for the distinction of meaningful and senseless propositions.

SEP - Frank Ramsey

Ramsey, as we saw in the previous section, was still an undergraduate when, aged 19, he completed a translation of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Wittgenstein 1922). Alas, C. K. Ogden got all the credit and it has been known since as the ‘Ogden translation’. Ramsey’s translation is usually considered to be superseded by the Pears-McGuinness translation (1961), but one should not lose sight of the fact that it was carefully scrutinized by Wittgenstein, who gave it his seal of approval. Ramsey then wrote a searching review of the Tractatus (1923) in which he raised many serious objections (Methven 2015, chapter 4) (Sullivan 2005). One such objections is the ‘colour-exclusion problem’ (1923, 473), against Wittgenstein’s claim in 6.3751 that it is “logically impossible” that a point in the visual field be both red and blue. This claim was linked to the requirement that elementary propositions be logically independent (otherwise, the analysis of the proposition would not be completed), a pillar of the Tractatus. Wittgenstein’s recognition in 1929 that he could not sustain his claim (Wittgenstein 1929), probably under pressure at that stage from discussions with Ramsey, was to provoke the downfall of the Tractatus.

Wittgenstein and the colour incompatibility problem - Dale Jacquette

What induced Wittgenstein to repudiate the logical atomism

I want to argue that Wittgenstein's abandonment of logical atomism and the development of his later philosophy was in large part the result of Ramsey's criticism of the Tractatus treatment of the color incompatibility problem, the problem of the apparent nonlogical impossibility of different colors occurring in a single place at the very same time.

Wittgenstein writes in Philosophical Grammar - "The proposition 'this place is now red' (or 'this circle is now red') can be called an elementary proposition if this means that it is neither a truth function of other propositions nor defined as such...But from 'a is now red' there follows 'a is now not green' and so elementary propositions in this sense aren't independent of each other like the elementary propositions in the calculus I once described - a calculus to which, misled as I was by a false notion of reduction, I thought that the whole use of propositions must be reducible". -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsAn elementary proposition is not "The car is red". This is a proposition capable of being true or false and depending on its veracity or falsity we can infer other propositions from it. — 013zen

Hopefully my question is not too far removed from the OP, the history of the Tractatus.

In the Tractatus, language can be analysed into logically independent components, known as elementary propositions.

Wittgenstein writes in 4.211 that it is the sign of an elementary proposition that there is no other elementary proposition contradicting it, meaning that it is metaphysically possible for each elementary proposition to be true or false independently.

However, Wittgenstein later began to realise that the logical atomism of the Tractatus was incapable of dealing with the colour incompatibility problem (aka colour exclusion problem).

In the colour exclusion problem, it's impossible for two different colours to occur at the same place simultaneously.

In 6.3751, as he writes that the simultaneous presence of two colours at the same place in the visual field is impossible, he also writes that a particle cannot have two different velocities at the same time.

Many simple colour propositions, such as "this car is red" and "this car is blue" fail the truth-functional combinations of elementary propositions, in that "this car" cannot be both red and blue simultaneously.

I agree that the colour exclusion problem wouldn't be relevant if elementary propositions are the logical form of the proposition, such as R(x) and B(x), where R and B are the predicates "is red" and "is blue". It is then the case that R(x) and B(x) are independent of each other.

But if elementary propositions are the logical form of the proposition, such as R(x) and B(x), then why did Wittgenstein turn away from the logical atomism of the Tractatus because of the colour exclusion problem? -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsYou mentioned the mystical. I see Schopenhauer in a way, as being an analytic mystic. — schopenhauer1

What is there about the writings of Wittgenstein that are so important yet are so difficult to express in words. As if we will be any closer to the value of his thoughts if we were able to put them in writing.

Can an aesthetic ever be expressed in words.

Wittgenstein has an aesthetic that is inexpressible in words, as a Derain has an aesthetic that is beyond the ability of language to explain.

Wittgenstein's value is in the aesthetic of his thoughts and writing, and as with a painting, or a sunset or flower, enables an aesthetic experience on the part of the reader, encouraging their application of taste and judgement.

For Hume, delicacy of taste is not merely "the ability to detect all the ingredients in a composition" but also the sensitivity to discriminate at a sensory level.

For Kant, "enjoyment" is the result when pleasure arises from sensation, but judging something to be "beautiful" has a third requirement: sensation must give rise to pleasure by engaging reflective contemplation.

There may be an aesthetic in both how something is expressed and what is expressed.

There is beauty in mathematics.

For Schopenhauer, the aesthetic experience involves a pure, will-less contemplation.

For Wittgenstein, ethics and aesthetics are the same

For Nietzsche, the aesthetics of morality establishes a form of life.

I am sure that part of Wittgenstein's importance is in the aesthetic of his thoughts, and as with Derain's painting of The Drying Sails 1905, can perhaps be described in words but never properly expressed in words.

His aesthetic cannot be said but must be shown.

(Using the Wikipedia article on Aesthetics) -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsI want from my philosopher reasoning and justifications for their assertions and claims. — schopenhauer1

The Tractatus is about the nature of language, using language to understand language, which is a logical impossibility. The task becomes that of the mystical.

6.522 There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.

Consider Schopenhauer's quote “The two enemies of human happiness are pain and boredom.” But to understand the quote one needs to understand the words "happiness", "pain" "boredom" which are impossible to describe using other words. So how to know what "happiness" means when it cannot be described.

6.53 The correct method in philosophy would really be the following: to say noting except what can be said, ie propositions of natural science ie, something that has nothing to do with philosophy - and then, whenever someone else wanted to say something metaphysical, to demonstrate to him that he had failed to give a meaning to certain signs in his propositions. Although it would not be satisfying to the other person - he would have the feeling that we were teaching him philosophy - this method would be the only strictly correct one.

It is only possible to understand language if one can understand the words being used in that language, and one can only understand those words using other words, which in their turn can only be understood by other words, leading to an infinite regress.

6.54 My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them – as steps – to climb up beyond them - (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it) He must transcend these propositions and then he will see the world aright.

Yes, perhaps a statement can be justified, but why stop there, why shouldn't the justification be justified, and then again, why not justify the justification of the justification.

7 What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsYou mention the supposed colour incompatibility problem, but to my understanding, this issue only crops up if you take the work to operate in a manner similar to Russell. — 013zen

Wittgenstein's logical atomism was different to that of Russell's, although they had some similarities (generally referring to SEP - Logical Atomism)

For Russell, the basic logical atom is the object, which can then be combined with other objects. For Wittgenstein, however, the basic logical atom is a state of affairs. a combination of objects.

Russell's logical atomism is epistemological. He gives no a priori argument for logical atomism, but can be empirically verified. Wittgenstein, however, gives an a priori argument for logical atomism requiring no empirical verification.

In the Tractatus is the principle of the logical atom. On the one hand, within language the elementary propositions are mutually independent and can be independently true or false. They are combinations of semantically simple symbols, ie names. On the other hand, each elementary proposition asserts the existence of atomic states of affairs in the world. These are combination s of simple objects, devoid of any complexity.

The Tractatus was written on the assumption that language may be analysed using truth-functions into elementary propositions that are independent of each other.

However, Wittgenstein gradually came to the conclusion that his project had failed.

Wittgenstein's turn away from logical atomism, the independence of elementary propositions, happened in two phases. Phase one with the 1929 article Some Remarks on Logical Form, the colour exclusion problem. Phase two 1931-32.

The colour-exclusion problem arises from 4.211, that it is metaphysically possible for each elementary proposition to be true or false independently.

Suppose P = "a is blue at t" and Q = "a is red at t". From empirical observation, P and Q cannot both be physically true. Wittgenstein was aware of the problem, yet thought with further analysis it could be shown not to be logically impossible.

The fact that we have never observed one object having two different colours at the same time does not mean a logical impossibility, after all, that an apple has the contemporaneous properties of sweetness and greenness is not a logical impossibility.

Given propositions P "A is blue at t" and Q "A is red at t", if P and Q are independent of each other, this means that object A i) can be blue and red ii) can be blue and not red iii) can not be blue and can be red and iv) can not be blue and not be red.

But what exactly is being combined in Wittgenstein's logical atomisms

First, Formal Concepts do not represent but are part of the logical structure and can only be shown.

Therefore we cannot say "there are objects", which is not depicting anything, but we can say "there are red objects", which is depicting something.4.1272 The same applies to the words "complex", "fact", "function", "number", etc. They all signify formal concepts, and are represented in conceptual notation by variables

4.1274 "To ask whether a formal concept exists is nonsensical"

As Russell writes in the Introduction "Objects can only be mentioned in connexion with some definite property"

Second, colour may be read as an object

From the article On the Nature of Tractatus Objects by Pasquale Frascolla, once objects are identified with those universal abstract entities which are qualia, some statements of the Tractatus become liable to a consistent reading.

2.0232 In a manner of speaking, objects are colourless

2.0251 Space, time and colour (beng coloured) are forms of objects

After all, if all the properties of an object were removed no object would remain, in that no object can exist in the absence of any property.

Then, using Russell's Theory of Descriptions, proposition P "A is blue at t" becomes "there is something that is the combination of object A with the colour blue" and proposition Q "A is red at t" becomes "there is something that is the combination of object A with the colour red".

The colour exclusion problem only arises in Wittgenstein' logical atomism, where the logical atom is in language the ontological combination of simple symbols and in the world the ontological combination of simple objects. IE, the incompatibility of the logical atom consisting of object A combined with blue and the logical atom consisting of object A combined with red.

Colour exclusion is not a problem for Russell's logical atomism, where the logical atom is the simple symbol in language which may then be non-ontologically combined with other simple symbols and the simple object in the world which may then be non-ontologically combined with other simple objects. IE, there is no incompatibility in the non-ontological combinations of object A, blue and red.

IE, The colour exclusion problem is problematic for Wittgenstein's logical atomism which depends on the combinations of objects, as such combined objects cannot be shown to be logically independent of each other. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsBut was Tractatus really aimed to dispute the position of mereological nihilism?............................How does he actually do that, rather than simply asserting premises that he thinks is true? — schopenhauer1

In the Tractatus, language shows the logical form of the world, and the world is the totality of facts.

But where exactly is this world?

It is said that the Tractatus can be read from both the viewpoint of Idealism, where the world exists in the mind, and from the viewpoint of Realism, where the world exists outside the mind.

If the Tractatus is attempting to show that language can be analysed into elementary propositions, where each elementary proposition is independent of all other elementary propositions, and where each elementary proposition pictures a fact in the world, then whether this world exists inside the mind or outside the mind is irrelevant

Therefore, the Tractatus need not pay any regard to Mereological Nihilism, which is is a philosophical idea specifically about a world that exists outside the mind.

As I can assert that "evil is bad" as a self-evident truth, perhaps the Tractatus can also assert that "the world is the totality of facts" as a self-evident truth. Anyone disagreeing that "evil is bad" or "the world is the totality of facts" then has the opportunity to present their argument.

After all, most of our statements are assertions, whether "I walked to the supermarket", "stealing is bad", "I admire Monet's aesthetic", "the world is a complex place" or "the play starts at 9pm". Rarely is it expected that we need to justify what seems to be self-evident. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsAlso, you didn't answer my question.. "What philosophy DOESN'T think their understanding of the world comprises independent facts"? I have yet to meet a person, who thinks "This is morally bad, or this is good" is the same as "The cat is on the mat." What problem then is he solving? — schopenhauer1

The Tractatus and facts

"The cat is on the mat" is true IFF (the cat is on the mat), where "the cat is on the mat" exists in language, and (the cat is on the mat) exists in the world.

The fact that (the cat is on the mat) in the world is dependent upon there being a relation between the cat and the mat. What is the nature of this relation?

Mereological Nihilism, aka compositional nihilism, is the philosophical position that in the world there are no objects with proper parts, in that there are no metaphysical relations that connect parts to a whole.

For example see:

1) Wikipedia – Mereological Nihilism

2) Amie L. Thomasson's video "Do tables and chairs really exist"

The SEP article on Bradley's Regress discusses the ontological debate between particulars and universals, where FH Bradley specifically outlined arguments against the relational unity of properties.

The SEP article on Relations notes that some philosophers are wary of admitting relations because they are difficult to locate. As it writes "Glasgow is west of Edinburgh. This tells us something about the locations of these two cities. But where is the relation that holds between them in virtue of which Glasgow is west of Edinburgh?"

IE, if a fact in the world is dependent upon the ontological existence of relations between parts, then if there are no such things as ontological relations in the world, then it follows that there are no facts in the world.

As the existence of ontological relations in the world would lead to philosophical puzzles, my belief is that relations don't ontologically exist in the world, thereby agreeing with mereological nihilism and concluding that there cannot be facts in the world.

In the event that there are no facts in the world, then neither can there be independent facts in the world. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsMy point is this: which philosophies argue that the world, at least in terms of human communication, is not composed of facts or true propositions?

For example, the statement "the unicorn is on the mat" is a false proposition because it's an impossibility. — schopenhauer1

Yes, there is no dispute that what is important in language are facts and true propositions, but the dispute arises in deciding what is a fact and what is a true proposition.

I believe that both unicorns and mats can exist, and therefore it's possible that there could be a unicorn on a mat. The statement "the unicorn is on the mat" could well be both a fact and a true proposition.

Unicorns certainly exist in literature, taking as a an example the book Into the Land of the Unicorns by Bruce Coville. Unicorns certainly exist in language, otherwise we couldn't be talking about them. The fact that no-one has seen or photographed a unicorn in the world is not proof that unicorns don't exist in the world, in the same way that because no-one has seen a particular rock at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, this is not proof that such a rock doesn't exist.

You believe that the statement "the unicorn is on the mat" is a false proposition. I believe that the statement could equally be a true proposition.

If I say, "the cat is on the mat," and we observe a cat on the mat, we might call this a true proposition.........................It's a truism. Almost no one disputes it. Well done for stating the obvious. — schopenhauer1

I am sure most are in agreement that "the cat is on the mat" is true IFF (the cat is on the mat), where the proposition "the cat is on the mat" exists in language and (the cat is on the mat) exists in the world. This is a truism that no-one would dispute.

We know where language exists. What is disputed in where this (world) exists. Does it exist in the mind of the observer, the position of Indirect Realism, or does it exist outside and independently of the mind, the position of the Direct Realist.

Yes, it is obvious that the cat exists in the world, but it is not obvious where this world exists.

So, I'm puzzled as to why a philosophy would assert, "My knowledge is made up of independent facts," as if this were a profound statement. — schopenhauer1

When starting the Tractatus, Wittgenstein did think that knowledge was made up of independent facts, but later concluded that his reasoning was unsound. He wrote Philosophical Investigations on the principle that facts cannot exist in isolation from each other.

According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, "profound" means having intellectual depth and insight.

On the one hand the statement "my knowledge is made up of independent facts" is philosophically profound, but on the other hand the statement "my knowledge is made up of inter-connected facts". is also philosophically profound.

What we want to know is which statement is true.

1) Similarly, stating truisms in philosophy without delving into the mechanisms behind them adds little value.

2) My broader point is that non-empirical philosophies can also be considered true propositions

3) If Wittgenstein isn't explaining why a proposition cannot be true, why should we care if the broader claim, "The world consists of true propositions or independent facts," is correct? — schopenhauer1

Aren't thoughts 1) and 2) in opposition.

I cannot justify in words my non-empirical thoughts that "evil is bad" and "beauty is good", yet I believe them to be true. I believe them to be truisms.

The only mechanism I can think of to explain such beliefs is that they have been programmed by evolution into the human gene for the benefit of the survival of the group.

As there are only 75 pages in the Tractatus, primarily devoted to Linguistics, I don't think we should also expect a foray into Evolutionary Biology, even if that is what he believed. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsIt was not addressed by Witt, but it SHOULD HAVE if his goal was to show how propositional logic allows for mapping onto reality due to selecting out true states of affairs; the MECHANISM for doing so must be EXPLAINED. — schopenhauer1

There is nothing wrong in making an assertion and not justifying it by a mechanism, which, after all, is the basis of scientific modelling. From Britannica Scientific Modelling

Scientific modelling, the generation of a physical, conceptual, or mathematical representation of a real phenomenon that is difficult to observe directly. Scientific models are used to explain and predict the behaviour of real objects or systems and are used in a variety of scientific disciplines, ranging from physics and chemistry to ecology and the Earth sciences.

I am in Crewe train station waiting to catch the train to London.

It is a fact that the train leaves from platform 4.

It is also a fact that the Eiffel Tower is 300m tall.

It is also a fact that the Great Northern is the highest selling beer in Australia.

It is also a fact that the capital of Nevada is Carson City.

My knowledge of the world is the set of these independent facts.

In the statement "my knowledge of the world is the set of these independent facts", whether the world exists in the mind (as proposed by Idealism) or exists independently of the mind (as proposed by Realism) is irrelevant to the truth of the statement.

That the sun rises in the east is explained by the model of the Earth rotating around the Sun. No mechanism for why the Earth rotates around the Sun is included within this model, as mechanisms are not part of models.

As Witt writes in the Tractatus:

and as a model the Picture Theory does not need to be justified by a mechanism.2.12 "A picture is a model of reality"

That the fact "the train leaves from platform 4" and the fact that "the Eiffel Tower is 300m tall" are independent facts is true, independently of any mechanism that could be used to justify it. That they are independent is a primitive truth.

That the colour red is not the colour green is true is also a primitive truth, and as such cannot be justified by any mechanism.

Yes, Wittgenstein in the Tractatus may make statements not justified by any mechanism, such as:

6.3751 For example, the simultaneous of two colours at the same place in the visual field is impossible, in fact logically impossible, since it is ruled out by the logical structure of colour.

But this is one of the major aspects of the Tractatus, that some truths cannot be described in words, but can only be shown

4.1212 What can be shown cannot be said

We all know that the colour red is not the colour green, and there is no mechanism that could justify such knowledge. As the Tractatus says, it cannot be said, it can only be shown. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsBut was that even addressed by Witt? — schopenhauer1

No, because that was not the purpose the Tractatus. The Tractatus was addressing a specific problem, not trying to explain every aspect of language.

The Tractatus was an attempt to show that we can analyse ordinary language propositions,

such as "the car is red and the car is on the road", into elementary propositions such as "the car is red" and "the car is on the road" which can then be combined using truth-functions. A proposition is elementary when it is independent of all other elementary propositions.

The Tractatus was an attempt to prove in one particular instance that a whole may be understood by understanding parts that are independent of each other.

Even if the Tractarian project failed because of the colour-incompatibility problem, the question of the relationship of the whole to its parts remains of philosophical interest. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughts1) (Donald Davidson and his article What Metaphors Mean)...........I take it he means only in scientific applications, yes? Either way, I personally find this view unintelligible at face value. 2) A voltage is quite literally, not a pressure. 3) We seem to have a simile of sorts, based on the definition; but the definition merely reports usage. — 013zen

This leads into the question as to how a model of the truth, the metaphorical truth, the simile as an expression of truth and the literal truth relate to the Picture Theory of the Tracatus.

The Picture Theory of the Tracatus

Before the Tractatus, philosophers thought that language mirrored reality.

Wittgenstein in the Tractatus introduced the idea that language doesn't mirror reality, but has the same logical form as reality.

2.12 "A picture is a model of reality"

On the one hand there is thought

3 "A logical picture of facts is a thought."

On the other hand there is are propositions

4.12 "Propositions can represent the whole of reality, but they cannot represent what they must have in common with reality in order to be able to represent it – logical form"

4.001 - "The totality of propositions is language."

There is the relation of thought with language.

4 "A thought is a proposition with a sense."

We can have the thought that the grass is green, and we can have the proposition that "the grass is green". The thought is the proposition, in that any thought must be expressible as a proposition, and any proposition must be expressible as a thought. Both the thought and proposition picture not reality but the logical form of reality.

However, only substances can be pictured, as only objects make up the substance of the world. As concepts such as god, religion, ethics, good, evil and morality are not substances, they cannot be pictured.

2.021 "Objects make up the substance of the world".7 "What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence".

Thoughts and propositions are an amalgam of Formal Concepts and Concepts Proper. Formal Concepts include things such as objects, events, things, numbers, complex, fact, functions and make up the logical framework of a thought and proposition. Concepts Proper such as mountains, hills, tables and chairs are what are being represented.

4.1272 The same applies to the words complex, fact, function, number, etc. They all signify formal concepts.

4.126 ..............I introduce this expression in order to exhibit the source of the confusion between formal concepts and concepts proper.............

The logical part of a thought or proposition does not tell us how the world is. For Wittgenstein, there is no synthetic a priori, as knowledge about the world only comes from observation of the world, and for the Tracatus a priori philosophising has no use.

The difference between Direct Realism and Indirect Realism

The Direct Realist believes that thoughts and propositions picture reality, whereas the Indirect Realist believes that the thoughts and propositions picture the logical form of reality.

Indirect realism is broadly equivalent to the scientific view of perception that subjects do not experience the external world as it really is, but perceive it through the lens of a conceptual framework. Conversely, direct realism postulates that conscious subjects view the world directly, treating concepts as a 1:1 correspondence. (Wikipedia Direct and indirect realism)

The Picture Theory is a model

A picture is a model

2.12 "A picture is a model of reality"

The Picture Theory cannot be literal

A picture cannot be literal, as a picture has the same logical form of reality, not the same form as reality.

If we picture an apple, as the picture cannot tell us about the form of reality, the picture cannot tell us what exists in the world, meaning that what exists in the world is unknowable, as is Kantian noumena. If the picture could tell us about the form of reality, then we would know what existed in the world.

Therefore the apple we picture doesn't exist in the world, but it does exist in the picture, otherwise we wouldn't be able to picture it.

The difference between metaphor and simile

From the Merriam Webster dictionary

Metaphor = a figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them (as in drowning in money)

Simile = a figure of speech comparing two unlike things that is often introduced by like or as (as in cheeks like roses)

To be a simile, the picture has to be like the logical form of reality, whilst to be a metaphor, the picture has to be the same as the logical form of reality.

For both the metaphor and simile there is a relation between two different things, whether Mr. S is a pig or Mr. S is like a pig. For a metaphor these two different things have a necessary property in common, whereas for a simile they only have a contingent property in common.

The Picture Theory cannot be that of a simile

The relationship between the picture and what is pictured cannot be that of a simile, as this would lead into an infinite regression, similar to the homunculus argument against Indirect Realism. This argues that the mind of the Indirect Realist is directed at an object, such as an apple, that represents another object, another apple, which in its turn represents another object, another apple -etc.

Similarly, the picture of an apple cannot be a picture of a representation of an apple, but must be a picture of an apple.

The Picture Theory must be that of a metaphor

In order to avoid this infinite regression, the picture must be of what is pictured. The picture of an apple must be the apple that is pictured, sharing the same necessary properties, and as such, a metaphor.

IE, the Picture Theory within the Tractatus is a metaphorical theory. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughts@013zen @Wayfarer

1) Voltage is not pressure; we are using one mode of thinking to facilitate another.

2) I've been mauling over recently if this is, perhaps, a re-envisioning of Maxwell's use of physical analogy in science, with the added concern of how to better adapt thought to those analogies in order to eliminate supposed "pseudo-problems".

3) .....................because all that is meant by "truth" is the correspondence, and whether or not there is such a correspondence, reality will tell us.

4) ..................there must be a certain conformity between nature and our thought. Experience teaches us that the requirement can be satisfied...............

5) But, then one can ask, in what sense can P, a proposition made up of words, correspond with reality made up of objects?

6) The map isn't a "true" representation of Boston but each map I look at has some of the correspondences with Boston and those correspondences might be "true" while others not. Reality is what tells you whether or not this is the case.

7) Is a volt a pressure? No, but certain similarities in one manner of thinking correspond to the other and can help to elucidate the other.

Taking the above into account, certain concepts may be helpful in working through the Tractatus.

What is the relationship between a model of the truth, a metaphorical truth, a simile expressing the truth or the literal truth

The Correspondence Theory means different things to different people

Correspondence means to have a close similarity, to match or agree almost entirely (Oxford Language Dictionary).

For the Direct Realist, as regards thought, if the Direct Realist sees a red postbox and thinks about this red postbox, their belief is that in the world exists a red postbox, and they are directly seeing it. Therefore, for the Direct Realist, there is no correspondence between what they see and think and what exists in the world, as what they see and think entirely agrees with what is in the world.

For the Indirect Realist, as regards thought, if the Indirect Realist sees a red postbox in the world and thinks about this red postbox, their belief is that in the world exists something that is not a red postbox but is causing them to see and think about a red postbox. Therefore, for the Indirect Realist, there is a correspondence between what they see and think and what exists in the world, as what they see and think only agrees with what is in the world.

As regards language, for both the Direct and Indirect Realist, there is a correspondence between the word and what exists in the world.

Therefore for Randall and Buchler, it is true that as regards thought, the Direct Realist believes they directly know reality and therefore don't need to compare their belief with the world, whereas for the Indirect Realist, as they believe they don't directly know reality, they therefore do need to compare their belief with the world.

What is a model of the truth

In thinking about why the sun rises in the east various models can be proposed. One model is that the Earth revolves around the sun. Another model is that the Sun was put into a chariot and everyday the God Helios would drive the chariot all along the sky causing the Sun to rise and set. It has been discovered that the model of the Earth revolving around the sun has proved more predictive that the model of the God Helio.

As any model can be improved, it is not that case that a particular model is wrong but that some models are more useful in particular contexts than others. For example, the model of the Earth revolving around the Sun may be more suitable in a science context, whereas the the model of the God Helios may be more suitable in a literary context.

It can also be seen that applying the wrong model in the wrong context may well result in unwanted philosophical problems which may well disappear if a more suitable model had been chosen. For example, on the one hand, using the God Helios model in a science context will clearly create philosophical problems that wouldn't have arisen if the Earth rotating around the Sun model was used. On the other hand, using the Earth rotating around the Sun model in the context of Greek mythology, in trying to understand the relationships between Helios and his parents Hyperion and Theia, will be clearly unhelpful

IE, no model is wrong in itself, but may be wrongly used. The purpose of a model is to be able to predict changes to the context within which it is being used.

Models, metaphors, similes and the literal truth in the example of seeing the colour "red"

If one sees the colour red, then one is thinking about the colour red.

1) For the Direct Realist, if one sees a red postbox then a red postbox exists in the world. The thought of a red postbox is neither a model, metaphor nor simile but is the literal truth.

2) a) For the Indirect Realist, if one sees a red postbox, the belief is that there is something in the world that caused the perception of such a red postbox. But what exactly that something is is unknowable, in the sense of Kant's noumena.

b) As regards models, the cause of what is seen can be modelled, such as a model of red postbox. Such a model exists in the mind and not the world, as the world is unknowable. The usefulness of the model is demonstrated by being able to predict changes in what is seen, not changes to what is in the world, but changes to what is seen.

c) However, it is a human characteristic to equate effect with cause. The cause of a bitter taste is a bitter drink, the cause of an acrid smell is acrid smoke, the cause of seeing the colour red is something that is red, the cause of heat on the skin is a hot object and the cause of a screeching noise is a screech. The effect is seeing a red postbox. The cause is categorised by the mind as a red postbox.

d) Therefore, what is the relation between what is seen (a red postbox) and what the mind has categorised as its cause (a red postbox). This relationship cannot be literal, as the effect is not the same as its cause. The relationship is not that of a simile, as the effect is not like the cause. The relationship must be that of a metaphor, because an identity has been assumed between two different things having a necessary property in common. Different in that one is an effect and the other is a cause, but sharing the necessary property that the mind has categorised the cause after the effect.

IE, for the Direct Realist seeing a red postbox is the literal truth and for the Indirect Realist seeing a red postbox is a metaphorical truth.

Models, metaphors, similes and the literal truth in the example of voltage and pressure

Is pressure a model, metaphor, simile or the literal truth in explaining voltage.

When one reads "Voltage is the pressure from an electrical circuit's power source that pushes charged electrons (current) through a conducting loop, enabling them to do work such as illuminating a light. In brief, voltage = pressure, and it is measured in volts" (www.fluke.com) - in what sense does voltage = pressure.

In the Merriam Webster dictionary, the word "pressure" has several meanings, including "the action of a force against an opposing force" and "voltage" as "potential difference expressed in volts".

We can model voltage by thinking about the pressure of water causing water to run when a tap is opened, where the pressure of water in pipes becomes a model for the voltage determining current in a wire.

As a simile, the pressure of water in pipes is like the voltage determining current in a wire.

It may be that originally pressure only referred to water, but the meaning of words is not predetermined, and the meaning of words change with time, sometimes becoming more generalised. As the Merriam Webster dictionary notes, pressure may be taken as the interaction between two forces, and with a change in meaning, rather than saying voltage in wires is like pressure in water, we can now use the metaphor that voltage is pressure.

However, this then takes us to Donald Davidson and his article What Metaphors Mean, where he argues that metaphors mean what their words literally mean and that there is no hidden metaphorical meaning. In effect, he is saying that what seem to be metaphors are in fact words being used literally. In the case of the seeming metaphorical expression "voltage is pressure", he is making the case that this means that voltage is literally pressure.

IE, even the expression "voltage is pressure" may be read not only as a model but also as a simile, metaphor and literally, all dependant upon one's point of view. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsI do wonder what if anything Witt can tell us today - even if I am correct that he did have something relevant to say to his contemporaries. — 013zen

As I see it:

As Kant successfully combined in his Critique of Pure Reason two prior theories previously thought independent of each other (Empiricism and Rationalism) into one, the synthetic a priori, Wittgenstein successfully combines in his Tractatus two prior theories previously thought independent of each other into one, (the Positivism of Mach and Ostwald and the model picture of reality of Hertz and Boltzmann) into one, language and thought as a logical picture of reality.

Positivism, in Western philosophy, is generally any system that confines itself to the data of experience and excludes a priori or metaphysical speculations.

For Boltzmann there is utility in a model corresponding with reality, and for Hertz, the thought of an image or picture, or the language of a sign or symbol, conforms with reality.

The Tracterian approach to language and thought as a logical picture of reality is equivalent to a metaphorical picture of reality

There are many articles that describe the language used by Wittgenstein in the Tractatus as metaphorical.

1) Wittgenstein and Metaphor, Jerry H. Gill, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research

2) Wittgenstein and metaphors in the Tractatus, Patrizia Piredda, 2021, Academia Letters

3) Wittgenstein’s Metaphors and His Pedagogical Philosophy, A Companion to Wittgenstein on Education.

One consequence of language as metaphor is the revolutionary idea that substance is able to traverse the actual and passible worlds rather than only underlying the actual world as traditionally thought. This solves the philosophical puzzle about how we are able to think about things that don't exist. Logical space is not the source of material change but of modal change (Kyle Banick - Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Metaphysics and Ontology, YouTube)

As regards terminology, I wouldn't call science's current approach a "metaphysical picture of reality", rather a metaphorical picture of reality. I agree about the importance of metaphor in how we understand the world, and as you say "Pressures and currents correspond to voltages and amps, despite energy not being transmitted in any similar regard whatsoever".

In the light of the Tractatus as proposing a metaphorical picture of reality, does this cast light on 6.54

Once I am able to metaphorically picture a voltage as a pressure, the metaphor becomes redundant. in that I now understand voltage as pressure. Not that voltage is like a pressure but rather voltage is a pressure. For Wittgenstein, the ladder is the metaphor, and can be thrown away as redundant once it has enabled understanding.My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognize them as nonsensical, when he has used them - as steps - to climb up beyond them (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed p it)

Many argue that language is metaphorical in nature.

1) Metaphors We Live By is a book by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson published in 1980. The book suggests metaphor is a tool that enables people to use what they know about their direct physical and social experiences to understand more abstract things like work, time, mental activity and feelings.

2) Andrew May in Metaphors in Science 2000 makes a strong point that even Newton's second law is a metaphor.

The Tractatus developed the Picture Theory of Language, language as metaphor, from which developed the modal notion of possible worlds. This was revolutionary in the 1920's, and as such relevant to his contemporaries. But this raises the question whether still of relevance today. I would say yes, for two reasons. First, language as metaphor and the modal notion of possible worlds are still relevant, and second, it appears that even today there are many who have not yet accepted these insights.

For example, Donald Davidson in his article What Metaphors Mean argues that metaphors mean what their words literally mean, in that they have no hidden meaning but can be explained by what they do within the context it is being used

In addition, those Direct Realists who believe that the world we see around us is the real world itself, things in the world are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

The insights of the Tractatus have still not been fully accepted, important though they are. -

The history surrounding the Tractatus and my personal thoughtsWitt himself says: — 013zen

“... I think there is some truth in my idea that I really only think reproductively. I don’t believe I have ever invented a line of thinking, I have always taken one over from someone else.........................What I invent are new similes”.

According to the SEP article on Ludwig Wittgenstein, "Considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century", and according to the IEP article on Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889—1951) "Ludwig Wittgenstein is one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, and regarded by some as the most important since Immanuel Kant".

So there must be more to Wittgenstein than he says of himself " I don’t believe I have ever invented a line of thinking". So the question is "what?"

Without wanting to overlap with @schopenhauer1 current thread on Wittgenstein, as you infer, no-one lives in a vacuum, including Wittgenstein when he wrote the Tractatus. So it cannot be that he did no more than cut and paste what was around him at the time, but must have creatively added something of significant originality.

It cannot be the case that his insights in the Tractatus have been superseded by his later works, or by more contemporary philosophers, as the Tractatus is still being discussed by contemporary philosophers as being of contemporary philosophic importance.

So even if the Tractatus is only an incomplete and partial explanation of the relationship between thought, language and the world, what original insights did it add to the contemporaneous debate between Mach/Ostwald on one side and Hertz/Boltzmann on the other?

Analogously, I am sure that no mark Monet ever made hadn't been made by a prior artist, so Monet's originality was not in the marks he made but in the relationship between the marks he made. Similarly, as with a simile, the originality is in the comparison between two things, not the things themselves. So we know Wittgenstein may well have borrowed ideas from both the empiricist and metaphysician, but where in the Tractatus is hidden his unique insight into the relationship between the empiricist and the metaphysical?

Though perhaps this is not directly relevant to the OP about the history surrounding the Tractatus, although maybe the question of why the Tractatus is important must be part of the history of the Tractatus. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff@Apustimelogist

There is only one Being, and it includes both sides of the Nature/Geist distinction — Count Timothy von Icarus

There is only one World

Yes, there is only one World. Humans are part of this World. From an Enactivist perspective, humans have evolved in synergy with the world, and the human mind has developed from its embodied interactions within the World.

As you rightly say " If we don't fall into the trap of thinking that relationships between knowers and objects are in some way "less real," than relationships between objects and other mindless objects, I think we avoid a lot of the problems of this distinction".

The mind is different to what is outside the mind

Within our minds we have the concept of "object", such as apples and tables, and in our minds we have the concept of number, such as the number 1 and the number 7. The question is, accepting that the human has evolved as part of the World, because we have in our minds the concepts of number and object, do numbers and objects of necessity exist in the World outside the mind.

The question can be extended. Because we have the concept of the colour red in our minds, does the colour red exist in the world outside the mind. Because we sometimes experience angst, does angst exist in the World outside the mind. Similarly, does pain, anger, fear, disgust, joy, surprise, anxiety, sadness and happiness exist in the World outside the mind.

It is true that there is one World, of which humans are a part, but it does not follow that what exists in the mind of necessity also exists outside the mind, otherwise, to make my point, the mining of anxiety would be as common as the mining of lithium. This is clearly not the case.

As you say "For example, it's impossible to explain the natural, physical properties of something without any reference to how it interacts with other things, the context it is situated in, etc." This is true, but as with angst, any such interaction is not of necessity between a world outside the mind and the mind, but may well be contained within the mind.

So we know that what exists in the mind does not of necessity exist outside the mind. This leaves the question as to whether our concepts of numbers and objects also exist outside the mind as numbers and objects.

Numbers and objects

Numbers and objects are Formal Concepts, in the sense as introduced by Wittgenstein in the Tractatus 4.126, and are to be distinguished from Proper Concepts such as "apple" or "table". Formal Concepts are part of the syntax of language rather than its semantics. Other Formal Concepts include the existential quantifier Ǝ "there exists", also a part of the syntax of language rather than its semantics. For this reason, as Wittgenstein notes, we cannot meaningfully say "there exists", "there are 100", "there are objects" as one can say "there exists a mountain", "there are 100 books" or "there are grey objects".

The concept of number is intimately linked with the concept of object, in that we cannot say "there are 100", as for the expression to be meaningful we must say "there are 100 apples", where the number 100 refers to the object apple. Any Formal Concept within a grammatical expression must involve a reference, ie, a Concept Proper.

I can say "I see one object, an apple". I can also say "I see two objects, the top of the apple and the bottom of the apple". I can also say "I see four objects, the top of the apple, the left of the apple, the bottom of the apple and the right of the apple". I can continue dividing the apple up, and increasing the number of objects I can see at each time.

But, as you say "That we can imagine a vast horizon of potential concepts does not entail their historical actualization". For practical and pragmatic reasons we just say "I can see one object, an apple".

The human mind can judge that a particular set of atoms exists as a single form, in this case, as a single apple. But the question remains, in the absence of a human mind, what determines that a particular set of atoms existing in space exists as a single object or not. What determines whether for example the loss of a single atom from an object causes the object to disappear from existence. What determines whether that atom was a necessary or contingent part of the object. The human mind can make such a judgement, but what what in the absence of the human mind can make such a judgement.

How can objects exist in the absence of the human mind if there is no mechanism for differentiating between different particular sets of atoms. What determines whether an individual atom is a necessary or contingent part of that object.

If objects cannot exist in the absence of the human mind, then numbers, which are intimately linked to the existence of objects, neither can exist in the absence of the human mind.

Quantifier Variance

As regards Quantifier Variance, we can consider the expression Ǝ n; n * n = 25. As the number n doesn't exist in the absence of the human mind, the expression cannot be referring to existence in the absence of the human mind but must be referring to existence in language and thought. Therefore, in this particular instance, it is not the existence quantifier E that is varying, but rather the predication of the existence quantifier that is varying.

Expanding on your thought that "There is a fundamental sense in which, conceptually, things can be defined in terms of "what they are not", I believe that we can better understand numbers when we appreciate that they have no existence in the absence of the human mind. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffLikewise, an explanation of counting seems to require some mention of the fact that the world already has things that we can count in it. — Count Timothy von Icarus

In the world we see an object on the left and we see an object on the right, and we say in the world there are two objects. From this we conclude that numbers exist in the world, as the object on the left and the object on the right exist independently of our observing them.

However, as objects in order to exist in the world have to be extended in space, the object on the left has both a top and a bottom. We can then justifiably say that in the world are three objects, the top object on the left, the bottom object on the left and the object on the right.

So are we looking at two objects or three objects? It depends on what an object is. Numbers cannot exist independently of the objects being numbered.

However, there is no means independent of the human mind to determine what an object is. IE, there is no means independent of the human mind to determine what makes a discrete object a discrete object. As @Srap Tasmaner pointed out, the problem of the edge case, and as you pointed out, the Ship of Theseus problem.

As there is no means independent of the human mind to determine what an object is, and as numbers are dependent upon the existence of discrete objects, numbers cannot exist independently of the human mind.

IE, it is a problem of circularity, in that there are two objects provided we have already determined that there are two objects. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffI don't see how DNA would explain that, rather it might explain why we see things in the same kinds of ways. — Janus

Humans have a general commonality, in that all the self-reproducing cellular organisms on the Earth so far examined have DNA as the genome (https: //onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

I agree that even though humans share a commonalty because of their shared DNA, in that both the Nominalists and Platonists accept that numbers exist, they may differ in their particular beliefs. The Nominalist's belief that numbers are invented and exist in the mind, and the Platonist's belief that numbers are discovered and exist in the world.

It is true that two identical objects may behave very differently when subject to different environments, whether a pebble moving down a slope or a pebble stationary on flat ground, whether a human living in Reykjavík or a human living in Pretoria. It is therefore hardly surprising that humans, even though they share a general commonality, may differ significantly in their particular beliefs and actions. It may well be that someone who is now a Nominalist who had had the life experiences of someone who is now a Platonist may well have turned out to be a Platonist and vice versa. As regards general commonality between humans, perhaps nature outweighs nurture, and as regards particular actions and beliefs, perhaps nurture outweighs nature.

As regards Quantifier-Variance, as Hale and Wright wrote: "[it may be] a matter of their protagonists choosing to use their quantifiers (and other associated vocabulary, such as ‛object’) to mean different things – so that in a sense they simply go past each other".

Particular differences are especially noticeable. The Nominalist may say that numbers exist in the mind and the Platonist may say that numbers exist in the world. But perhaps QV is pointing out a hidden commonality in seemingly different beliefs, in that an individuals actions and beliefs are determined as much by their lived life experiences as by innate characteristics, as much as by nurture as nature

An individual's actions and beliefs should not be considered in isolation at one particular moment in time, but should be thought of as part of a process stretching back many years. If someone does say "‛there exists something which is a compound of this pencil and your left ear’ and someone else says ‛there is nothing which is composed of that pencil and my left ear’, perhaps QV is making the point that these statements should not be considered in isolation as necessarily contradictory, but rather should be considered as a glimpse of an ever-changing process stretching back in time, embodied not just in one or two individuals but in the multi-various life experiences of whole communities.

IE, perhaps QV is saying that individual statements, such as "numbers only exist in the mind", should not be judged as true or false in isolation from the wider community out of which it has emerged, in that particular words only have meaning within a wider context. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffHow would that work? — Janus

How does commonality between humans work because of their shared DNA?

For the same reason that there is more commonality between humans who share 99.9% of their DNA than commonality between humans and chickens who only share 60% of their DNA (https://thednatests.com) -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffOther than positing some hidden connection between all minds, there is no way to explain the commonality of human experience, a commonality that extends even to some animals. — Janus

That humans share 99.9% of their DNA (essential for development, survival and reproduction) with other humans may explain the commonality of human experience (https://thednatests.com) -

Which theory of time is the most evidence-based?Which theory of time is the most evidence-based? — Truth Seeker

Perhaps the same could be said about space. In a similar way to Presentism, it could be said that only the space that I exist in is real, and any space outside is simply a construct of my consciousness.

This approach has the advantage of treating space and time as two aspects of the same thing, ie, space-time.