Comments

-

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaHard to make an argument without the text but I would say my reading here of Chapter IV is a start—basically Austin is saying philosophy made up the idea of perception (as an assumption to fill a place in an argument based on our errors and mistakes), and we have other ways of judging everything that is supposed to do.

-

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaAs I see it, the problem is only "manufactured" if we buy into the idea that there is only one correct way to think about it. Otherwise, you just have different ways of thinking and talking about perception. — Janus

I'm saying, along with Austin, that there is no correct way to consider "perception" because philosophy did not think about it, as in look into how it would work and whether anything else was actually resolving those issues. Philosophy created a boogyman to slide in the only kind of answer it would accept, certain knowledge. The book is attached above in one of my posts if you care to discuss. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @J @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997 @Ciceronianus @frank @wonderer1@Janus

Sec V: I’m going to point out again the importance here to Austin of context and standards.

[With a blue imagine and blue wall, or bent pencil in water or just a bent pencil] we may say the same things ('It looks blue', 'It looks bent', &c.), but this is no reason at all for denying the obvious fact that the 'experiences' are different. — Austin, p. 50

This is going to be confusing for some of you maybe as he is not using “experience” as something only we have (thus putting it in quotes, as if Ayer would say this is some process of the mind), but these are two different situations (the "context" is different), and that we would judge them separately based on the different associated standards, and not simply by “direct or not”. Philosophy wants to treat everything the same without regard for the surroundings, or, as Austin puts it, the “extraneous” and “attendant” “concomitants” (accompaniments).

Next Ayer and Price try to argue that, if we are deluded, two things must be indistinguishable (that we have no way of judging between direct or indirect, thus why they claim we can only see sense data). But this is to ignore that we might not be using, or aware of, criteria to differentiate, as with tea experts, art critics, or eloquence.

Perhaps I should have noticed the difference if I had been more careful or attentive; perhaps I am just bad at things of this sort (e.g. vintages); perhaps, again, I have never learned to discriminate between them, or haven't had much practice at it. — Austin, p. 51

And so philosophy is jumping to conclusions without even investigating our various standards and not taking into account any kind of context. “[The] conclusion [we always see sense-datum] is practically assumed from the very first sentence of the statement of the argument itself.” p.47 “[We are asked to] concede the essential point [‘perceptions’ are always present] from the beginning.” Id.

Why would philosophy want an answer that only fits two standards and is abstracted from any context? Why would it want "perception" and "sense data" to come between us and the world? (These are rhetorical questions.) -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaIs he dismantling anything or merely presenting a different way of thinking about it. — Janus

He is not presenting a different way of thinking (another answer or theory) about this (manufactured) problem of direct or indirect access (and all the related philosophical manifestations). He is showing us how things work to make it clear that the philosopher created this distinction (with pre-defined reasons for a certain answer). So, yes, he is dismantling, and not only the entire framework, but showing how errors in these related activities are normally resolved in different ways (showing that skepticism is not an issue for philosophy with just one face). He does also have important things to say, about: our variety of activities, the role of context, the different criteria for judgment of each thing, etc. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia...I still feel the classic account of indirect perception which has been around from the time of Plato is more reasonable. — Corvus

...where he discusses difference in usage of the words "looks" "seems" and "appears" ...was more like English semantic chapter rather than Philosophy... — Corvus

Well I'll leave you to it, only to say that taking these points as a matter of "semantics" is due to underestimating that he is dismantling the "classic account of indirect perception" from Plato through Descartes and as it remains these days, with Ayer as only one proponent but with the same reasons and same means. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

It is not a different interest. It was just part of the explanation why perceptions are indirect. Austin's first page of the book is about direct and indirect perceptions. — Corvus

Philosophy created the idea of "perception" and the idea that they are "indirect" (as with Hume's appearance, Plato's shadows, etc.). That people imagine science can explain these particular phantasms is just where science is barking up the wrong tree in trying to solve the mistakes of philosophy. Again, that is not to say there are not things to learn about the brain, just not these things to solve a problem philosophy mistakenly created.

Austin is simply investigating Ayer's creation of the distinction in dismantling the whole framework of direct/indirect as well as "perception". I can go over any of the text you take to lead to that conclusion. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @J @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997 @Ciceronianus @frank

We need to get past the picture of a process called "perception". If nothing else, Austin has shown that this is a figment that is simply manufactured by philosophy.

(emphasis added)Anyway, pointing out the eyes as a medium for visual perception is not such a nonsensical statement. — Corvus

"Perception" is just a catch-all for: seeing, looking, identifying, grouping, judging, etc. (as well as, elsewhere: thinking, understanding, intending, etc.) in order for philosophy to frame the issue as a specific type of singular problem. But all these other things are not internal processes, but are each separate activities (like actions) that are done by public mechanics (standards) that allow for rectifying errors and debate (see Sec. IV).

I think he accepts that perception involves a fair amount of interpretation. — frank

He would say that we do not each have "our perception" and then we debate those, but that the things we interpret are publicly judged by standards that we share. And so "interpretation" is a public process of argument taking into consideration that we have to apply those standards. By Austin's method, we would understand "interpretation" by looking at the kinds of things we say about what we "interpret", as in commenting about a painting (which is a thing we are interpreting), or making explicit the implications of a text (which is a skill, again, involving some thing, say, like a rule, or a someone's hand gestures),

[Eyes as a medium for visual perception] could be actually a legitimate scientific statement. — Corvus

Now to say we have brains and they allow us to have senses, like vision, smell, touch, and we can study those, is an entirely different matter than our public practices. In doing philosophy we are not doing science, although as much as science imagines a mysterious process of "perception" that it can know, it is taking a fantasy of philosophy and treating it like a biological conundrum.

But also, whatever science learns about the brain is not going to resolve the issues of philosophy like skepticism of our relation to the world and each other (which creates the need for something to solve that "problem", here, by "direct perception". Or, when finding philosophy can't have the immediate or certain "knowledge" it desired (as a prerequisite), it does not admit the whole framework was wrong, but makes it about an imagined failing of our nature and creates "indirect perception" (appearances, etc.).

obviously there are objects and the perceiver in this issue — Corvus

But, having taken all that down a peg, this is just to say that you are not me, and I am not the world (because the world is not in my head, however "indirect", causing yours to be a different world). I do have personal tastes, interests, desires, commitments, guilt, motivations, etc. These are not wrapped up in a single theoretical conceptualization of "my perception".

When you are asked how a car works, could you explain the workings of cars without going into the explanations on how the engine, steering and gear works? — Corvus

Austin is explaining how looking, seeing, etc. work. If science wants to study what happens to the brain when these things are going on, then that is just a different interest, but these practices are not discrete functions or processes of the brain (though the brain does do other stuff). -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @J @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997 @Ciceronianus @frank

Part of the difficulty is understanding the significance of what he says. It is too easy to trivialize "ordinary language". — Ludwig V

I tried to take a stab at this confusion above in saying Austin is not taking the views of the common person to address the concerns of philosophy (to say they conflict). He is employing a new (old) method that by looking at what we ordinarily say (in the course of business) shows (is evidence, but not “empirical” @javi2541997) that we have way more standards then philosophy’s singular standard (direct or not). It is not that our ordinary activities solve philosophy’s problems, but only show that philosophy turned our concerns into a problem it created only able to be solved by a particular (direct, objective, scientific) solution, however mysterious (and so Austin is deconstructing metaphysics @javi2541997).

But I think that is a reaction to the difficulty of seeing what one might do next in philosophy. So much is being dismantled that the landscape can seem to be a desert. Bringing the nonsense in philosophy to an end is one thing. But bringing philosophy to an end is something else. Whatever motivates philosophy has certainly not gone away. — Ludwig V

This method is to draw out our ways of judging (which we rarely examine), in the same way Socrates did, but without jumping to (starting with really) the standard that we must end up with a type of knowledge that fixes the precipitous conclusions that philosophy imagines (skepticism, relativism) because it does not take into account the ordinary ways we have of resolving our errors and conflicting cases. This doesn’t finish philosophy but only shows that we can disagree on rational terms where philosophy did not think it was capable only because it set the standard for rationality up front.

Wittgenstein will echo that this method “seems only to destroy everything interesting, that is, all that is great and important? (As it were all the buildings, leaving behind only bits of stone and rubble.)” #118 But he will focus on the outcome that we now have a clear view, that there is a value in the discovery. The work on morality, other minds, etc. are each different, and continue. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaIs that consistent with me using a cup to trap a spider?

People surely have the ability to see ways of using things, in ways no one has before. So surely what we 'see' is more than just previously recognized linguistic and usage associations? — wonderer1

But “creative” problem solving and “imaginative” ways of using things are based on the fact that we have had practices like holding in cups, trapping things, pacifism, etc. and not a matter of “seeing” as if it were attached to vision. But, yes, our practices are not closed off from innovation. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @J @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997 @Ciceronianus @frank

I wanted to point out that part of the confusion here is that we (and most everyone in philosophy in general) do not take what Austin is doing as revolutionary and radical as it is. He is not offering another theory to explain “perceiving” or something to replace it. He is claiming that the problem that everyone is arguing about how to solve is made up; that the whole picture that we somehow interpret or experience remotely (through something else--sense perception, language, etc.) or individually (each of us) is a false premise and forced framework.

It might appear that Austin is just being snobby about words or is only making a claim that language is the right filter for the world, etc. But his method (as with Wittgenstein) is to set out what we say and do about a topic as evidence of how that thing actually works. That is to say, he is learning about the world. For example, in examining what we say and do about looking, he is making a claim about how "looking" works, the mechanics of it. “Seeing” something is not biological—which would simply be vision—and neither is judging, identifying, categorizing, etc. (“perception” is a made up thing, never defined nor explained p. 47). . Austin is showing us that “seeing” is a learned, public process (of focus and identification). “Do you see that? What, that dog? That’s not a dog, it’s a giant rabbit; see the ears.”

So, again, he is not saying we experience the world directly or indirectly--he is throwing out the entire picture of us (here) and the world (there) that leads to that distinction. This, for some, is very hard to wrap their heads around because it means letting go of a fixed, certain world, even, as is the case here (and with Kant), when we can’t or don’t know it.

As examples:

"It’s a shame Austin doesn’t wade into any of these problems …and is content to split-hairs on rather trivial matters, like an entire lecture on the word 'real'."

"there is not much significance in delving into the differentiation of direct and indirect perception because from my point of view, all perceptions are somehow indirect from the minimal perspective that for any human perception, it will happen via proper and relevant sense organs"

“sense organs are not the final perception location in the process, then they have to be the medium passing the sensed contents into the final location i.e. the brain”

“I think perspective - subject and object - is based on two main categories: the external, which essentially treats all things as objects and ignores the subject” -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @J @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997 @Ciceronianus

Having gotten through Lecture IV: this is an example of where Austin takes a deep-dive into the differences between ordinary "uses" of words that philosophy takes as terms for a special purpose, but I think Austin somethings buries the point of all this. ("uses" here are the different "ways in which 'looks like' may be meant and may be taken p.40)

I'm going to take a stab at putting the dots together, but I do think the way he talks about it (below) needs to be accounted for. I take him to be showing how different uses (of like or seems) each have different things that matter to us about them, different ways we judge them, including: whether they are analogous or divergent 36 whether evidence is used 37 that there are different kinds of evidence 39 sometimes only needing a "general impression" 39 what "complications are attributable" 39 what they "well might be mistaken for" 42

I take these various standards and features to show that there are many different means of judging, rather than only whether we see it (directly) or do not see it; which is the point at which philosophy adds something in-between, like "sense-data", because then the standard can be unqualified across instances, locations, and everything sensed. But just because we can make a mistake does not mean we have to interpret sensations as always open to explanation by faulty sensors, as errors can be corrected because there is "nothing in principle final, conclusive, irrefutable about anyone's statement" and that I can "retract my statement or at least amend." 43

There is also, again, that judging these cases is different in different contexts, or that there needs to be a correct context, such as: "particular" and "special circumstances" and "suitable contexts" 39 that we need to look at the "full circumstances of particular cases" 39 or that how it is used will "depend on further facts about the occasion of utterance;"

I also want to note that these means of judgment are "our normal interests" 38 in these things, because it opens the question of what philosophy's interests are in its one standard (directness) without regard to instance or context which I take as the desire to "rule out uncertainty altogether, or every possibility of being challenged and perhaps proved wrong."

And to internalize our possibility of failure makes it a problem with me ("my" perception), or with humanity (some faculty or process), but Austin is claiming that our standards and circumstances that frame how these issue play out means that "I am not disclosing a fact about myself" because "the way things look is, in general, just as much a fact about the world, just as open to public confirmation or challenge, as the way things are. p 43 (emphasis added). How can it be only your perception when what you see incorrectly can be pointed out by me? -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia“Pure sensation” or “qualia” or whatever term you prefer is what we call the unabstracted perception, the unconceptualized sensation specific to one setting and one time. We then go on to “see X” based on what we’ve learned about how to see. I think Austin considers this issue of “seeing as . . .” later in the book. — J

The point about abstraction is a note on Austin's method. If we ignore all the uses of a term in all its various contexts (as Austin brings back), then we narrow our understanding of, say, "direct" and "material objects", etc. and our picture becomes unconnected from our lives.

But I may not be understanding you. How does any of this problematize sensing? — J

The fact that we make mistakes, mis-identify, are tricked, and all the other things Austin explores, should point (as Austin does) to the ordinary ways by which we resolve those issues. Philosophy turns these instances into a intellectualized "problem" which underlies all cases, thus unconnected from our procedures and familiarity, because it can then have one solution, here "direct perception", or "qualia". -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaI was just responding to the other members queries on the points. You got to give out your points as clearly as possible, if you had one, when asked, don't you? :) — Corvus

I was not intending to suppress discussion. It just helps me to respond to the text and how we are interpreting that, which is what I am trying to focus on discussing--not "my" points, but Austin's--which I see as different than just expressing our views on this issue. But, feel free. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

He quibbles throughout, but then says that, according to the argument from illusion, sense-data is perceived directly. — NOS4A2

the argument from illusion is intended primarily to persuade us that, in certain exceptional, abnormal situations, what we perceive—directly anyway—is a sense-datum

This is confusing, but if we break it down: they are trying (but fail) to persuade us that we only can "directly" perceive sense datum, because of the problems brought up in certain circumstances which they want to say creates a problem with perception. This is not an admission by Austin that we perceive things directly, but simply stating the argument they are making in creating the indirect/direct distinction. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

-

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaAustin intimates somewhere, all perception is direct. — NOS4A2

Austin is specifically tearing down philosophy's framing of the issue as both direct or indirect. As he says:

"It is essential, here as elsewhere, to abandon old habits of Gleichschaltung, the deeply ingrained worship of tidy-looking dichotomies. I am not, then-and this is a point to be clear about from the beginning-going to maintain that we ought to be 'realists', to embrace, that is, the doctrine that we do perceive material things (or objects)." p.3 -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaMy problem is that I can't imagine what direct perception would be. Isn't this part of what we need to recognize here? If nothing could count as direct perception, then the idea that perception is actually indirect doesn't make sense. The problem is the move from "some perception is indirect" to "all perception is indirect". — Ludwig V

But I agree that setting this issue aside enables us to understand what is going on here better, even though I'm not entirely sure that the last word has been said here. (I have in mind Cavell's idea that the idea of a last word on scepticism is a mistake.) — Ludwig V

He’s not done yet, for sure. But the argument is that discussions about indirect perception make sense, but not as thought of in contrast to direct perception. Which means we don’t need the idea of sense data at all. It would just be “perceiving” but I believe the next move is that we don’t even understand what “perception” is (if we talk about sense perception, what is direct touch? direct smell? etc.)

Does such a position [with qualia] involve believing in sense-data? — J

The argument for sense perceptions, or data, and qualia (and appearances, and particulars) have in common that we are problematizing sensing in a particular way—by abstraction from any setting—and creating one answer because we believe there is always a problem (and that we want to buffer ourselves from the possibility of any). However, Austin has just shown that the problems we have with sensing are ordinary and resolvable at the ground level, so both the abstraction from any case, and the generalization to all cases is unnecessary. There is more. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @“J” @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997

Having finished Lecture III, I noticed that Austin continues to bring up normal cases. This is part of his method, but he only hints at it. At p. 31 though, he says that “we must remember what sort of situation we are dealing with.” (Emphasis added) Wittgenstein will insist on the importance to philosophy of “command[ing] a clear view” PI #122 and of the need for a “particular” p.188, “wider” #539 “great variety of” p. 181, or even “imagined” context and will remind us to “Remember that…” #33, 88, 161, 167, 217, 269, p. 191, p. 207, or to “remember actual cases…”; #147 and #591, as “In what sort of context does it occur?” P. 188.

The situation we are to put these claims into, and what we are remembering about the context of those situations, are the “public” “standard procedures” p. 24 and “normal occurrences” or “normal find[ings]” with which we are “familiar” p. 26. I think he gets at why when he says we see “exactly what we expect” (emphasis added) because our common expectations are what we see, only to have them disappointed. It is philosophy that makes it a disappointment with (our) “perception”. (Do we bring the disappointment inside of us to have control? As then we might be able to make sure we don’t fail again?).

As he showed in the case of deception, we only recognize the odd case against normal ones. P. 11. You are only able to be surprised by an illusion because you were normally expecting something else. Thus why it is important to put these claims into a situation and context to see what the normal procedures, standards, expectations, implications, and findings are for that kind of thing (delusion, mis-identification, deception, etc.). Wittgenstein will call these ordinary criteria.

One question could be: what about this method is important? (other than having someone set out an example and I actual say.. “oh yeah, he’s right”), but the more interesting question is why philosophy wants to abstract from any context and our ordinary means of judgment? but that is not under discussion here. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaBut my biggest puzzle is what would count as direct perception. — Ludwig V

Austin’s point of showing how “indirect” perception actually works is to show that in no instance is it the opposite of what we imagine direct perception would be the perfect case of. So if we set aside the problem of direct or indirect, we can look and identify the actual mistakes we make in seeing something, identifying something, or whatever else is supposed to fall under the imagined process of “perceiving” something (more than just simply vision). “…it seems that what we are to be said to perceive indirectly is never—is not the kind of thing which ever could be—perceived directly. P. 19. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno @“J” @Ludvig @Corvus @javi2541997

I forgot to tag people in my above post, but I also wanted to bring attention to Sec. 3 on page 9 where Austin comments that philosophers like to point out that they are noticing something that ordinary people do not; that philosophy is more aware, smarter, etc. And, yes, philosophy's job is to reflect and reveal what we don’t normally consider everyday. And Austin seems to breeze by this, at least for now. But I want to point out that, yes, there are problems, and mistakes, and falsehood, and ignorance, etc. and that philosophy is trying to record that fact. The only problem is that philosophy starts with simplifying the problem (to perception, appearance, etc.) and forcing a single answer (something "real", "objective"), rather than what Austin is doing here which is to examine how our failings are varied and thus have various ordinary ways in which we account for them. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@Banno

I think it needs to be reiterated that Austin is peeling away the logic of assuming mistakes about seeing things are evidence of a generalized problem with the faculty of our senses or something “after” that, as in “when something is amiss (that his 'senses are deceiving him' and he is not 'perceiving material things')” p 9

One of the problems he sees is that philosophy takes it that perceiving always works the same way as perceiving objects rather than all the ways we see, and thus the different ways we have trouble (other than just with our senses) seeing “people, people's voices, rivers, mountains, flames, rain-bows, shadows, pictures on the screen at the cinema, pictures in books or hung on walls, vapours, gases-all of which people say that they see or (in some cases) hear or smell, i.e. 'perceive'. Are these all 'material things'?” P. 8

Again, just because we have problems simply means in each case there is a separate logic of ordinary error. But the philosopher wants to group all the different errors into one problem (with perception) with one answer: flawed “Perception” compared to say “reality”. As Austin says, "...there is no neat and simple dichotomy between things going right and things going wrong; things may go wrong, as we really all know quite well, in lots of different ways-which don't have to be, and must not be assumed to be, classifiable in any general fashion." Such as something wrong with our ability to perceive anything at all (which we should also keep in mind is only one example of philosophies desire to create a problem as one kind of thing, as with: appearances, beliefs, subjective, morality, etc.) -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

Oh no need to apologize. It’s just I can’t do two things at once. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

I don’t know what you are quoting; I was referring to Austin’s lecture, which is what we are reading. I thiink it would be getting ahead of ourselves to take into considerations other readings before we attempt our own or even have a clear view of what he is saying at way, as he is only collecting evidence and has not gotten to why the philosopher wants to have a generalized problem with everything we see all the time “already, from the very beginning” p. 8. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaYes, I was somewhat concerned not to present Wittgenstein's view. — Banno

I’ll leave him out of it; only complicate things. One book at a time. But, come on…

“It is a matter of unpicking… fallacies… which leaves us, in a sense, just where we began.” P. 5

“…we may learn … a technique… for dissolving philosophical worries…” Id. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaBasically, I think that reality does exist objectively. — javi2541997

There is a part in this (very small) lecture where he addresses “real” and “reality”. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaPerception is far more than just to say, what I see is "real", and that is it. The aftermath of perception is more complex, deep, rich and meaningful in human perception. — Corvus

If we read on, perception is used as a straw man for any problems in the “aftermath of perception”, but “seeing” a table is to identify something as a table, which is judging whether something is a table, or, say, a bench (that we somehow mis-identify as a table) and not a matter “after” perception, but I’m getting ahead of the text. “…our senses are dumb… [they] do not tell us anything, true or false. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaDo you mean that it would be more accurate to say "roughly correct" or "very good approximation of the actual shape"? — J

I’m saying that “correct” is made up as a part of the “perception” of “actual” because the real issue is the identification of the table, judging whether it is a table or a bench, and thus “roughly” a table is a rock with a board on it. But I jump ahead I think; I’m going to read along. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia[Arguments against Ayer] 4. …it is also implied, even taken for granted, that there is room for doubt and suspicion” - Austin — Austin

For how can I go so far as to try to use language to get between pain and its expression? — Witt, PI 245

Can't we imagine a rule determining the application of a rule, and a doubt which it removes—and so on? But that is not to say that we are in doubt because it is possible for us to imagine a doubt. — Wittgenstein, PI#84 -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia@“J” @“Jamal”

I was thinking @“Banno” that I’ll just follow along in the book and ask when there’s something I never got about this, and then we can all make the most sense out of what he’s saying before we jump to judging the argument. -

Austin: Sense and Sensibilia

I really hate being misquoted — Jamal

OOHH.... that is entirely my bad. I was rushing and crammed your sentence in with Russell's, probably among other errors. Apologies. And if I ran roughshod over your point or concerns, I jumped the gun a bit on assessing them I'm sure. I'm just a little excited to have anyone talking about this book. -

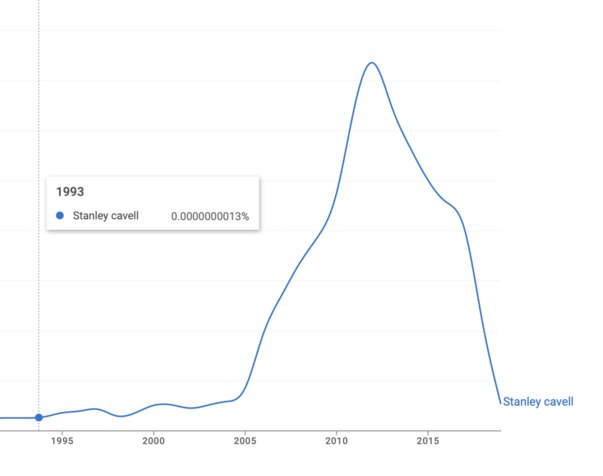

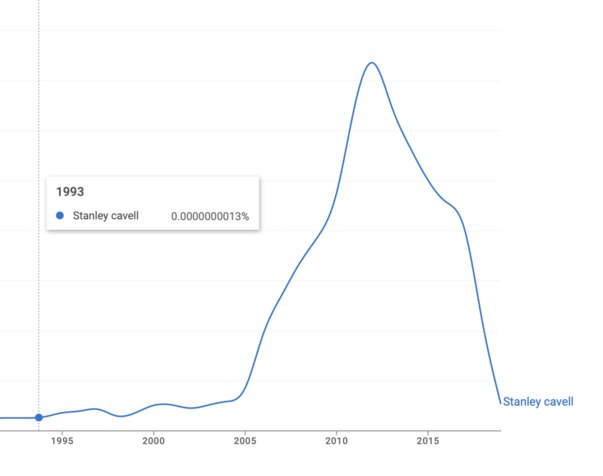

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaA quick look at Austin's book ngram shows continuous, perhaps even exponential, growth. — Banno

There goes my degree. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaOne of my favorite books @Banno, thanks for doing this (good luck).

There's the bit where you say it and the bit where you take it back. — Austin

"What we should figure out, is knowledge... well, we tried. Then virtue!... nope, not that either." Plato

"Let's start with the thing-in-itself; and then set it over here behind this wall." Kant

"I exist! Or, if that's okay with you God." Descartes

"I see it! No, wait, that's only its appearance." Hume

His target is the idea that we only ever see things indirectly. — Banno

I think Austin is wrong to quibble about the terms “direct” and “indirect”, because both succinctly describe the relationship between perceiver and perceived as it pertains to the arguments for and against realism…. But in terms of realism, “directly” and “indirectly” describe the perceptual relationship between the man and everything he perceives, which includes the periscope, the air, the clouds, etc. — NOS4A2

He’s investigating how we see something directly by looking at the actual cases when we do, and then how we see something indirectly through different examples, to show that philosophy made up the problem of realism. I think the book might be interesting to you.

This talk of “not directly perceiving objects” makes me wonder, not for the first time, who Austin believed he was arguing against. Did he think that Idealism in general, or versions of Kantianism in particular, entailed such a view? I don’t think that’s a very charitable interpretation of what I take Kant and others to be saying — J

Wittgenstein will look further into why philosophy created a problem with sense perception, belief, appearance, subjectivity, etc., but Austin is taking down everybody’s problematizing of the issues which led to metaphysics and justified true belief and Ayer’s Atomism and Positivism and qualia, etc. because they all have in common that they want everything to work one way that allows for absolute universal, generalized, proven, predictable, etc., knowledge. There’s a reason we get stuck on logical/emotive, true/false, knowledge/belief, etc. and that is because we are only looking at one version that is resolved one way, as, in the case of perception:

The reason is simple: "There is no one kind of thing that we perceive, but many different kinds" — Banno

Austin - Sense and Sensibilia 1962; Wittgenstein - Philosophical Investigations 1958. They never met, but they should have. Wittgenstein will look at how we think a bunch of things work, like language, and rules, seeing, identifying color, etc., and decide there is not one way we judge how things work, but many different ways.

[Looking at false dichotomies like direct/indirect] is a standard critical tool for Austin, used elsewhere to show philosophical abuse of "real". — Banno

In A Plea for Excuses, he will label this “The Importance of Negations and Opposites” in a discussion of freewill based on looking at action—using another tool of Austin’s, which is to look at how something works by looking at how it doesn’t work, how it goes wrong; in the case of action, by looking at how we excuse it, qualify it, renounce it, etc.—he actually looks at how voluntary and involuntary are so different it doesn’t make sense to manufacture the issues as: was that done freely (voluntarily)? or was it determined (involuntarily)?

(emphasis added by Nickles)And it is certainly true that we construct the correct shape from a multiplicity of individual "takes." …In Russell's sense of "real" -- a perception that corresponds fortuitously to an actual shape — J

(emphasis added by Nickles)The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known. If there are any directly perceived objects at all for Russell, they are sense data, not tables — Jamal

I can’t recommend reading this book more; Austin will have a lot to say about philosophy’s use of these words. Austin causes us to reconsider why philosophy creates a problem so it can solve it (@J why is the shape “correct” and “actual”, and not just roughly? - @jamal what does perception have to be immediate and direct in order to ensure? (spoiler!: it’s because we only want to answer one way, to one standard.)

talk of deception only makes sense against a background in which we understand what it is like not to be deceive. — Banno

Elsewhere he will say, basically, "intention" only makes sense (compared to imagining it as a cause) when someone does something "fishy" against a background in which we have ordinary, shared expectations. As in, "Did you intend to run that light?"

But notice that the contrast between philosophers and ordinary folk is borrowed from Ayer. — Banno

I just want to add that a common confusion is that Austin's method is pitting regular ol' common-sense people against esoteric philosophers, or as if “ordinary” was popularity—just taking a study, as if his philosophy was sociology. The common folk are all of us together who work within Wittgenstein's various criteria that are “ordinary” only compared to the single "prefabricated, metaphysical" criteria of certain, justified knowledge that philosophy uses. -

Austin: Sense and SensibiliaI wasn't able to find a free PDF. If you have access to one, you might link it here. — Banno

Attached is a PDF of the book Sense and Sensibilia.

Come on and get me Oxford. I got a sandwich and a gun. -

Rhees on understanding others and Wittgenstein’s "strange" peopleI do not know in advance how deep my agreement with myself is, how far responsibility for the language may run. — Minar's paper

What does "agreement with myself" mean? — Luke

This is a lot in one sentence, but I know what Minar is trying to get at. Our language reflects our interests and judgments (as Wittgenstein sees), and, so, in a sense, reflects who we are (by default—see my discussion about the self and conformity). If I am to use language responsibly, then, in saying something, I consent to be judged by it, for its criteria to be what matters to me. However, at a point (in time I argue elsewhere), my consent to be spoken for by language, as Minar says, “may run” out. This is to break with my culture, to stand against it, “adverse” (Emerson says in Self Reliance) to what language demands that we answer for; that I refuse to be determined by the shared judgments we make from it.

“If language really were a technique, then…. there would be no connexion between philosophy and scepticism. You should not understand what was meant by the notion of the distrust of understanding.”

— Rhees, as quoted in Minar's paper

I take the argument here to be that if language were a technique then there should be perfect understanding and no room for scepticism or doubt. — Luke

Yes, that is the implication. To say we “should not understand what was meant [by skepticism]” is a bit dramatic, fanciful. To make this more pedestrian, if traditional philosophy had its way, then what I say would be certain to you if I only mastered language. I would have control of the “meaning” of what I say, as if there were something in me, say, “my understanding” (or “intention”, or “thought”) which only fails because language is flawed, not able to capture my unique specialness, or I am just not good enough at it, when it is really the other way around. I am only as much as I capture in language (or action); but I don’t just either do that or not, because my expressions are mine to own (or not), as if they were my promise. Thus I can continue to make them intelligible, ask they be forgiven, take them back as poorly said, attempt to weasel out of the consequences of their inherent implications, etc. -

Rhees on understanding others and Wittgenstein’s "strange" peopleHow can Cavell reject the thesis of skepticism - that we do not know the world or other minds with certainty - while also claiming that skepticism is a natural possibility which results from having language? [that] the "truth of skepticism" is not a metaphysical dissatisfaction with knowledge, but is instead an expression of "the urge to transcend the human". — Luke

Minar is accurate and tells the story with all the parts, but it’s lacking in paraphrasing, unpacking Cavell’s terms of art. I am impressed and thankful you read the paper though and these are exactly the right questions to ask. I think how I put this to @Bano here might be a good start.

Summarizing that story, out of our fear of the other, philosophy created an intellectual problem of doubt about them that knowledge could then try to solve (with metaphysics, etc.), when the skeptic is right that there is no fact of the other (or ourselves) to know that will resolve our worries. But Wittgenstein sees that this truth is only because our relation to others (the mechanics of it, the grammar) is not through knowledge resolving our doubts about them, but that it is part of our situation as humans that we are separate, that our knowledge of the other is finite. But the implications of that are simply that the ordinary mechanics of our relation to others is not one of, here, knowing “their understanding”, but of accepting or rejecting them; that their otherness is at times a moral claim on us, to respond to them (or ignore them), to be someone for them. Thus “the urge to transcend the human”, in our ordinary lives, is to avoid exposing ourselves to the judgment of who we are in how we relate to others. In the case of understanding, by only wanting to treat what others say as information we simply need to get correct, rather than acknowledge their concerns and interests, and have ours be questioned. To put it that this is the “result of having language” is the picture of something like that what we say has a “meaning” that stands alone from who we will be judged to be in having said it, rather than it expressing us, allowing who we are to be read through it. -

Rhees on understanding others and Wittgenstein’s "strange" peopleI am a little unclear what you mean by "Wittgenstein's strange people", but based on the cited paragraph, it could mean people who you may find difficult to understand. — Richard B

Sorry, the sentence before (which I have also referred to) and the passage from p 223 of the PI, 3rd, in its entirety (emphasis in the original) is:

“If I see someone writhing in pain with evident cause I do not think: all the same, his feelings are hidden from me.

We also say of some people that they are transparent to us. It is, however, important as regards this observation that one human being can be a complete enigma to another. We learn this when we come into a strange country with entirely strange traditions; and, what is more, even given a mastery of the country's language. We do not understand the people. (And not because of not knowing what they are saying to themselves.) We cannot find our feet with them.” -

Rhees on understanding others and Wittgenstein’s "strange" people

One area I believe we can agree on is Wittgenstein's pointing out the importance "of natural actions and reactions that come before language and are not the result of thought."…

'You say you take care of a man who groans, because experience has taught you that you yourself groan when you feel such-and-such. but since in fact you don't make any such inference, we can abandon the argument from analogy' (Zettel, 537) — Richard B

Yes, we do not know the other because we infer them from our experience. But we do not know the other because of our shared history of actions and reactions either—we do not know the other. As I have been saying, the “natural actions and reactions” to others are the particular mechanics of our relation. Thus, it is no longer a “problem” to be solved by knowledge, by analogy or otherwise. Part of the workings of our natural actions and reactions to the other is that sometimes we can’t predict them, we aren’t sure they will agree with us, follow us, remain consistent to our expectations of them, etc. We sometimes cannot find our feet with them, understand them. This is not a philosophical problem; it is part of the human condition. So, instead of intellectually trying to “solve” or minimize it, we are simply trying to make explicit the (unspoken) ordinary criteria we live with for what counts in terms of getting to know someone.

Antony Nickles

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum