-

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas"Odd, how again folk will do anything to avoid actually reading the text that is the very topic of the thread.

-

A Case for Moral Anti-realismA sharp question.

The main motivation against moral realism, especially around here, is the naturalism that takes scientific fact as the only sort of truth worthy of the title. The notion has a strong place in pop science culture, and comes to us mainly from the logical empiricists, Ayer and Carnap and so on. They denigrate moral language as not based on scientific reality, and by extension seek to mark ethical statements as not truth-apt; as being mere opinion or taste or some such, and hence (somewhat inconsistently) as being neither true nor false.

This motivation was clear in the present thread. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism

-

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI can’t find my way to truth in this. — Tom Storm

But you have your foundational principles - that is, you take them to be true. Hence you are a moral realist.

How you justify that belief is over to you, and irrelevant to whether you are a moral realist or not. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI guess the same way I justify aesthetic taste. — Tom Storm

I'm not asking you to justify your moral stance, but to explain how it can be not true. In aesthetic terms, you claim would have to be that despite, say, liking sugar in your morning coffee, you do not think it true that "Tom likes sugar in his morning coffee".

Yep. Another way to say this is that there is broad intersubjective agreement as to what is true....there’s broad intersubjective agreement about many matters based on a shared human experience — Tom Storm

Good. Now if you are a moral realist, you would say that "we should not cause suffering" is true. If you reject moral realism, you somehow have to maintain that we should not cause suffering, and yet deny that "we should not cause suffering" is true.I am happy with a foundational principle such as, we should not cause suffering... — Tom Storm

Gets complex, doesn't it. It's hard to have a foundational principle that is not true.

What you have brought ought here is that the justification is a seperate issue to the truth of the proposal. The point has been made several times throughout this thread, by a few of the more well-versed folk, but some are deaf to it. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI know where I stand on some moral questions — Tom Storm

So you know where you stand on moral questions, but you do not consider those statements that set out that stance to be true?

How can that be made coherent? You know things that are not true?

Again, moral realism is simply the view that there are true moral statements. Are you sure you reject this? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismIn the Philpapers survey, 2020, just under 70% accepted or leaned towards moral cognitivism.

62% leaned toward moral realism.

Not as high as for external word realism, but perhaps enough to show our anti-realist and non-cognitivist friends hereabouts that they might have missed something. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI'll repeat the simple point that I am not here attempting anything like a coherent, complete theory of ethics, but simply pointing out that there are true moral statements.

Those who have disagreed have either claimed that it is false that one ought not kick puppies for fun, or engaged in the special pleading that despite common usage it is neither true nor false.

Neither reply is tenable. -

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas"

The quote is Ryle, not I; so it's not I who does not say. One charitably presumes that here, in the first chapter, he is setting a direction, on which he continues in the remainder of the book.And why is that? You do not say. — Fooloso4

There's something disingenuous about launching into a critique in your first post. You seem to be treating an introductory remark as if it were the whole proposal.

But further, your critique looks misplaced.

It seems from this that you think making a category error as carving stuff up wrong. I hope it's clear from the SEP article that it's more about taking a term from one category and misapplying it in another. It's not failing to clearly differentiate between colour and texture, but "the number two is blue". The "pat rejoinder" is to attempt to apply Ryle's own processing to himself, while apparently misunderstanding what that process is.Ryle is making his own version of category mistake when he attempts to cleanly and neatly divide things along the lines of categories, as if cutting along the inherent joints of things rather than in conformity to some disciplinary practice. — Fooloso4

We might here agree to set aside these relatively pedantic issues and continue with the next lecture. -

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas"Well, earlier in the paragraph is writ: "I have said that when intellectual positions are at cross-purposes in the manner which I have sketchily described and illustrated, the solution of their quarrel cannot come from any further internal corroboration of either position." It is apparent that biology and physics, melded into biophysics, are not at cross-purposes. It seems to me somewhat crude to take the one example to undermine Ryle's point when there are others at hand that serve him better. We might better understand his work if we are a bit more charitable.

The SEP article I linked shows the history of the approach Ryle adopted, presenting numerous examples where "intellectual positions are at cross- purposes", so it's not as if this never happens. Spotting category mistakes is part of the analytic toolkit.

Isn't launching into a criticism based on a single example from the introduction somewhat premature? The danger is that we trot out the pat rejoinders rather than pay attention to the text at hand. If it is your first time reading Ryle, then let's read Ryle. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?The flowers are Potentilla erecta, which have four true petals.

-

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas"I must be missing your point; nothing in that is about "cross-disciplinary studies such as biophysics".

-

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas". But cross-disciplinary studies such as biophysics seems to contradict this. — Fooloso4

Then perhaps he is on about something else. -

Reading Gilbert Ryle's "Dilemmas"Thank you, .

As the engram shows, Ryle was well thought of in the Sixties and Seventies, but has scarcely dimmed since then. He occupies a singular place in the history of Philosophy, as what is misleadingly known as Ordinary Language Philosophy moved through considerations of intentionality into the recent work on Consciousness and Philosophy of Mind. Ryle is a progenitor of this path, his main contribution being the book The Concept of Mind, in which he coined the term "Ghost in the machine" and developed the philosophical notion of the "category mistake".

But here we have a discussion of what might loosely be called "domains of discourse", where what we have to say about a topic, considered in one way, is utterly at odds with what we have to say when we consider the very same topic in another way. We would talk of one having responsibility what one does, until we talk about what caused us to act, and responsibility no longer enters into the issue. We would talk about what we see or hear, until we talk about the physiology of perception, and cease to mention seeing and hearing, instead talking or nerves and physics. How can this be? -

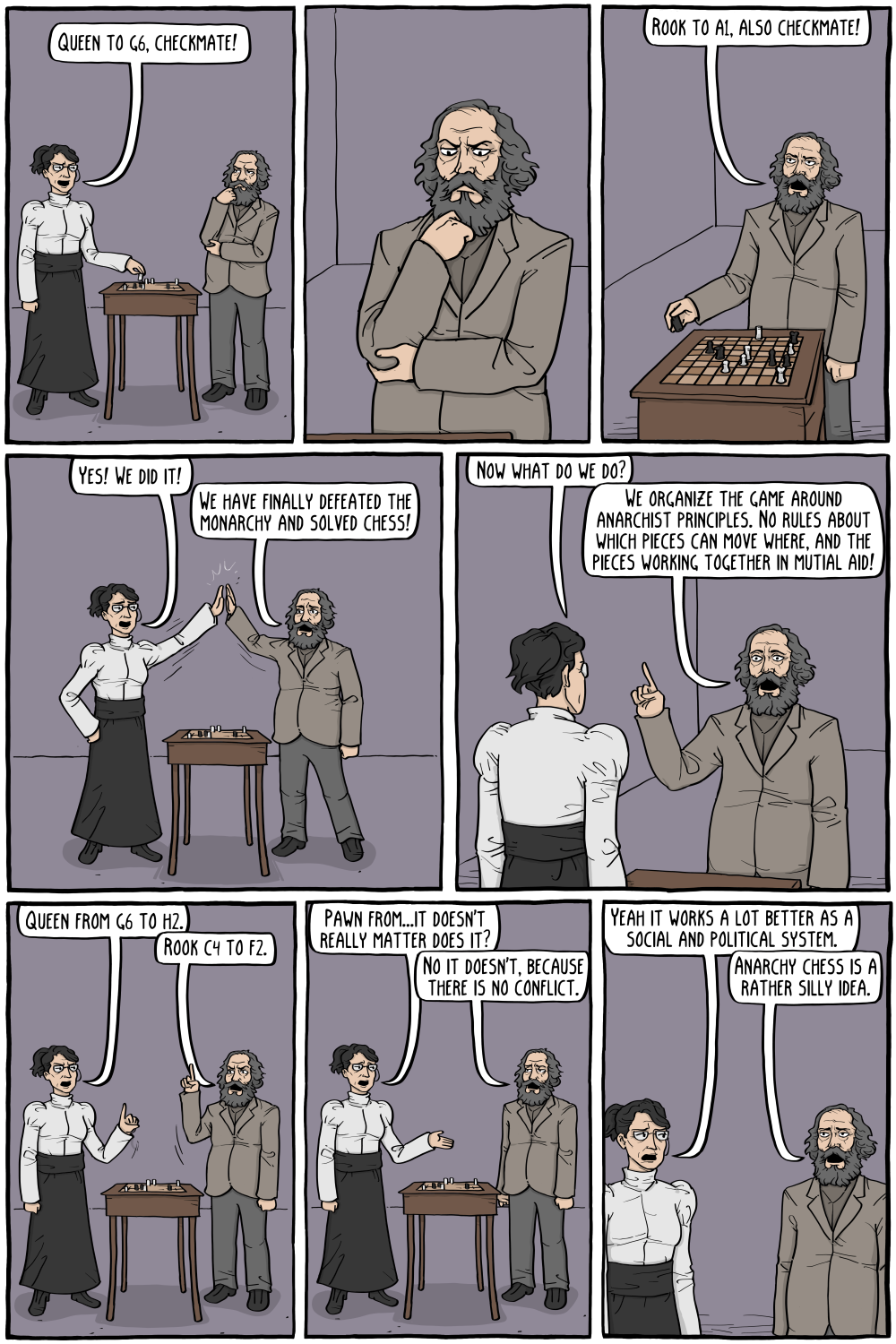

A Case for Moral Anti-realismPropositions about the rules of chess may be true or false. The rules of chess may not be. Try harder. — hypericin

Is "The player with the white pieces commences the game" true, false, or not truth apt? Or are you going to claim that "The player with the white pieces commences the game" is a proposition about the rules of chess, not a rule of chess?1.1 The game of chess is played between two opponents who move their pieces alternately

on a square board called a ‘chessboard’. The player with the white pieces commences the game. A player is said to ‘have the move’, when his opponent’s move has been ‘made’. — FIDE Laws of Chess

It's true, because if it were not, we could not form an argument such as

- The player with the white pieces commences the game.

- Fred has the white pieces.

- therefore Fred commences the game.

This thread has degenerated to imbecility. Have fun. :roll: -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismAgain, that describes how people talk about truth but it doesn't in and of itself tell you if something is true or truthapt. — Apustimelogist

Well, it was good enough for Tarski, Davidson and one or two others.

Nothing - any more than something stops someone from starting with g as 10m/s/s. Either way, they may find it difficult to maintain consistency. What makes it true that "g is 9.8m/s/s" is exactly that g is 9.8m/s/s.So what stops someone from starting from a different assumption about whether one ought to cause suffering? — Apustimelogist

Its very easy, you can talk about it in terms of things like goals, actions, their consequences and reason using them instead. People do it every day concerning the things they want to do and the ends they want to realize to decide what behaviors they want to do. — Apustimelogist

How do you set out the "ends they want to realize " without an evaluation? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismYes, something along those lines. Any theory that requires differing senses of truth is to my eye dubious. I'd apply Searle's analysis, using status functions - "counts as" sentences. Moving along a diagonal "counts as" a move in chess, and so on. No need to re-think truth in order to play chess, which strikes me as a huge advantage.

I suspect neither of our interlocutors have the background to follow this discussion. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism

Well, "one ought not kick puppies for fun" will be true if and only if one ought not kick puppies for fun.What makes it true? — Apustimelogist

That's about all one can say, but I suspect you will not be happy with it. You probably want to ask how we know it is true, and my own answer is that it's a consequence of the hinge proposition that one ought so far as one can avoid causing suffering. And we "know" that to be true. With all the usual considerations invovled in hinge propositions.

Can you show how one does that if normative statements have no truth value?Its very easy to reason about normativity in terms of some kind of means-ends analysis. — Apustimelogist -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismHis point, though, is that the rules taken as a whole, or the game taken as a whole, are apparently not truth-apt: — Leontiskos

Yes, I saw that. I can't see how one could play chess if he were right. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism:rofl: Oh, I see - taking the turn of phrase literally.

So you think "One ought not kick puppies for fun" is neither true nor false? Or do you think it false? -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismEven if the rules of chess cannot be true... — Leontiskos

...and what I said above applies here too. If the rules of chess are neither true nor false, then they cannot be used in deductions such as:

- One wins if one places one's opponents King is checkmate

- Leontiskos placed his opponents king in checkmate.

- Therefore Leontiskos wins.

Is this what is being suggested? If the major premise is neither true nor false, no one can win. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism...you are perceiving truth in it... — AmadeusD

I've no idea what that might mean. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realismI'm going to repeat the two objections to the idea that value statements do not have truth value.

First, it seems that they do have truth value. So "one ought not kick puppies for fun" is a valuation. And it gives every appearance of being true. Therefore there are true valuations.

Second, if valuations are not the sort of thing that can be true, then they cannot be used in deductions or explanation. If "Banno likes Vanilla" is not true, then it cannot be used to explain why Banno usually buys vanilla ice cream and vanilla milkshakes. If "One ought not keep slaves" is neither true nor false, then it cannot be used to reach conclusions such as

- One ought not keep slaves

- Alice keeps slaves

- Alice does what one ought not do.

And so on. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

I think we talked about this before. Error depends on things mostly being right.Could not everything be in error — Tom Storm

Arriving at the truth is adopting a belief. Belief and truth are different things. I think we looked at this before. Propositions are true, or not: P is true. Propositions are believed, or not, by people. Tom believes that P is true. Most statements are true or false regardless of their being apprehended or understood.But is not truth finally something we have to arrive at via apprehending and understanding? — Tom Storm

Folk hereabouts fumble that difference.

And some truths are contingent - that I just and a flat white - others not so much - that a flat white is a flat white. -

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implications

There's a need for precision in the language used in situations such as this.I do not see what my eyes see. — Art48

So one reply is that your eyes don't see - you see, using your eyes. Your eyes are a part of you.

Similarly, it's not that your mind process the information and presents it to you - as if your mind were not you - as you say with "my mind processes the light reaching my eyes and presents me with the image I do see".

Your eyes, the various parts of your optic nerves, the visual cortex - it's clearer to say these are the parts of your body you use to see rather than that saying that they produce the image you see, as if they were seperate from you. This helps avoid thinking in terms of the homunculus. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

A better answer is the obvious point that there are different ways of using an expression such as "I see the flower". I supose we might feel sympathy for those who cannot see flowers.What do we mean when we say "I see X"? — Ciceronianus -

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implications

Ok, so let's set it out clearly.The argument is in the OP. — Art48

- Suppose two "perspectives" - first person and third.

- Posit that we cannot know what causes our sensations.

- Supose first person accounts to be "more certain" than third person accounts.

- Conclude that one doesn't see what one's eyes see.

Now I don't follow that. The argument is incomplete.

Contrary to your first assumption, we do often - although not always - know the source of our sensations. For example, the source of your sensation of this sentence is this sentence.

And it is a common supposition in the sciences and in law that third person accounts, being depersonalised, are better than first person accounts. That they are objective. We can be more confident about observations that can be repeated by others.

So I remain unconvinced.

You seem to be saying that if we accept inconsistency, then we can no longer do logic.

Ok, but isn't a better conclusion that we ought not accept inconsistency? Conclude that not everything is relative?

And it doesn't address the invalidity of "...since we cannot think without using our mind, therefore whatever we think cannot claim any truth". -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?So the issue becomes how to consolidate the two...

The answer is in the difference between belief and truth. What you believe, in your terms, is down to "apprehend and understand our world subject to frames of reference and emersion... in the human experience". Notice this is about what we apprehend and understand, not about what is true.

What we apprehend and understand can be in error. One might apprehend the flower as having three petals, despite it having four. In which case, the flower has four petals regardless of what is supposed. -

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implicationsThere is a rather slight argument supposing that because we sometimes see illusions, we therefore never see reality.

And yet, the one proposing this argument is certain that they see the illusion.

But of course no one here would propose anything so silly. -

A Case for Moral Anti-realism~~ Your posts would improve if you were to use "preference" in preference to "taste".

-

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implications

You can see that the argument is invalid. It says "A, therefore B".My conclusion is that, since we cannot think without using our mind, therefore whatever we think cannot claim any truth, any reality, any objectivity. — Angelo Cannata

But it also contradicts itself, if it claims to be true; since if it is true, then we cannot claim it to be true.

So it doesn't seem right. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?

Yeah, all that guff and misrepresentation. How many petals does the flower have? I say four. Your answer?

I don't agree. The flower has four petals regardless of what you suppose. That we see, feel, count or believe that it has four petals is incidental, post hoc.There is no flower with four petals , or any other visually identifiable object, until we first establish these relational interactions between ourselves and the world. — Joshs -

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implicationsOk, so if that's not your conclusion, what is?

-

The Adelson Checker Shadow Illusion and implications

What is the argument?But I don’t see a flaw in the argument. — Art48

Consider, if you can, that you are aware of the situation. You understand that the two squares that look to be different shades are the same shade, and that this has been done in order to construct a picture of a partially shaded checkerboard.

The supposedly problematic central square is the shade it would be if we were looking at a real floor with one of the light checks in shadow.

There is no problem here, just a demonstration of how perceptions work.

So what is your argument?

You suppose two "perspectives" - first person and third. You posit that we cannot know what causes our sensations, despite the evidence to the contrary. You supose first person accounts to be "more certain" Then of a sudden you jump to "I do not even directly experience physical sensations".

There's no connection here between premise and conclusion.

Banno

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum