-

A Wittgenstein CommentaryNot so. The colour green is the propensity of an object to preferentially reflect light of wavelength 550nm approx. — unenlightened

Yes, some objects in the world have the propensity to preferentially reflect light of wavelength 550nm.

Humans have defined the wavelength of 550nm as green. Then where does green exist? Although a wavelength of 550nm can exist in the world, green can only exist as part of a human definition, and human definitions can only exist in the mind, not the world.

The wavelength of 550nm could equally well have been defined as violet. There is nothing in the world outside the mind that is able to determine whether a wavelength of 550nm is green or violet. Only in the human mind can it be determined that a wavelength of 550nm is green and not violet.

As the colour of the wavelength 550nm can only be determined by the mind, the colour green can only exist in the mind. -

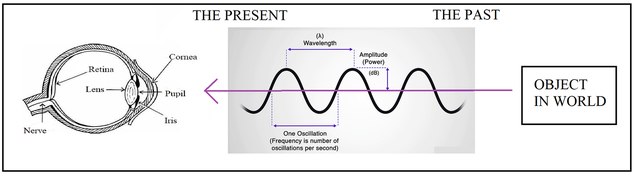

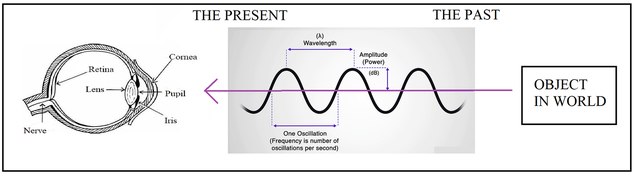

A Wittgenstein CommentaryI passed it by, because you have just explained perfectly precisely how an observer sees a past event, which any astronomer can confirm as perfectly normal and universal.. — unenlightened

Exactly, the fact that the event is in the past means that the the observer cannot see the event directly, only indirectly, which is the position of Indirect Realism. Another argument against Direct Realism.

The eye detects light and distinguishes the wavelength and this is how the information is 'conveyed'. — unenlightened

Exactly, "beauty is in the eye of the beholder". The colour green exists in the mind, not the world, which is the position of Indirect Realism. Yet another argument against Direct Realism. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryWe use the same word for the radiation and its source; perhaps that observation might help folk see the light? — unenlightened

Yes, that is the problem. If a wavelength of 550nm enters the eye originating from an object in the world, in common language we say "I see a green object".

As you said yourself "There is no such thing as green light because light is not visible; there are green sources of light and green reflectors of light."

This is the problem with Direct Realism, which believes that the world we see around us is the real world itself, where things in the world are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

This is why I wrote "The problem is that the light emitted from the object happened at a time before entering the eye, and the philosophical question for the Direct Realist is how is it possible for an observer to directly see a past event?"

Another problem for the Direct Realist is, if it is true that the object has an the intrinsic colour of green, how does the information that the object is green get to the observer, if the means of getting the information to the observer, the wavelength of 550nm, carries no information about colour. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryNo one sees light, it is not visible. — unenlightened

The general opinion is that humans can see light, for example:

Wikipedia: "Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye."

National Geographic Society: "Visible light waves are the only wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum that humans can see"

BBC: "Everything we can see is because of how our eyes detect the light around us."

NASA: "All electromagnetic radiation is light, but we can only see a small portion of this radiation—the portion we call visible light." -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryIn the meantime, I will stick with the runner beans that are green, and maintain that they and their greenness are in the garden and not in my eyes which are greyish blue, nor in my mind which is quite clear — unenlightened

The observer sees green light (ignoring for the sake of argument that this wavelength after entering the eye becomes an electrical signal that travels up the optic nerve to the brain).

This green light has been caused by something in the world. The light left the object before being seen by the observer.

The observer directly sees the green light as it enters the eye, and not the green light as it was emitted from the object, as the light emitted from the object was emitted at a time prior to entering the eye. An observer cannot directly see an event that happened in the past, only an event in the present.

As many causes of green light are possible, and as the observer has no direct knowledge of the cause of the green light, the observer's belief that the cause were runner beans can only be indirectly inferred from the other senses, such as touch, smell and taste.

We understand reality by using multiple measurements to abstract out the same pattern. This is known as Construct Validation in psychology. This raises the question as to how we know when a concept is real, how do we know the nature of reality. To establish something as real, we need a set of qualitatively different measurements which converge, which is what the senses do. The senses provide five qualitatively distinct reports, and if they converge one presumes that this constitutes reality. This convergence of the senses is how we define reality.

That the cause of the green light were runner beans cannot be directly known by sight alone. All that is possible is a justified belief from the rational combination of different senses that the cause of one's seeing green light were green runner beans.

The problem is that the light emitted from the object happened at a time before entering the eye, and the philosophical question for the Direct Realist is how is it possible for an observer to directly see a past event? -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryI use my eyes, personally. The runner beans I can see through the window here are green with orange-red flowers. The runner beans are in the garden. What I cannot see, because my eyes do not point the right way, is into my mind. So I confess I do not know how my mind distinguishes things. I distinguish colours using my eyes, though; I'm fairly sure of that. — unenlightened

In perceiving runner beans, the Direct Realist would say that what we see exists in the world, where things in the world are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence. The Indirect Realist would say that our conscious experience is not of the real world itself but of an internal representation, where our ideas of the world are interpretations of sensory input derived from a real external world.

Science tells us that a wavelength of 550nm travels from the runner beans to our eyes, where an electromagnetic wave is an oscillation of electric and magnetic fields and its wavelength is the distance between two adjacent crests.

How can a wavelength of 550nm have an intrinsic colour, and if wavelengths have an intrinsic colour, what would be the intrinsic colour of a radio wave having a wavelength of 3 metres ?

I'm also pretty sure I do not look at my sensations to see what colour they are, because I would need special eyes in my my mind that I do not think I have. And even supposing I did, they would surely require eyes in the mind's eye to examine the sensations produced, and those eyes would also need eyes to look at their sensations etc, ad infinitum. — unenlightened

I agree, which is my argument that it is more the case that "I am sensations" rather than "I have sensations".

From Wikipedia Homunculus Argument

If there is a homunculus looking at sensations, these sensations must be in the homuncules' head. But how does the homunculus see sensations inside its own head. It can only be if there is a second homunculus within the first homuncules head looking at the sensations within the first homuncules head. But then we have the same problem, how does the second homuncules see sensations inside its own head.

A dualist might argue that the homunculus inside the brain is an immaterial one, such as the Cartesian soul. A non-dualist might argue that a life form is indivisible from its environment, such that the mind is not separate from its sensations, but rather the mind is the set of its sensations.

A dualist would need to explain how a mind separate to the body can affect the body. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryI prefer to say that sensations are not the kind of thing that has colour. The sensation of green is no more green than the sensation of big is big, or the sensation of having made a mistake is a mistake. — unenlightened

The sensation of green is a different thing to the sensation of big, so the expressions "the sensation of green is green" and "the sensation of big is big" cannot be equated. We directly sense the colour "green", but we don't directly sense the adjective "big". Whereas "green " is a direct sensation, "big" is not a direct sensation.

In the mind are sensations. The question is, how does the mind relate to its sensations. Either the mind is separate to its sensations, such that "I have sensations" or the mind is its sensations, such that "I am my sensations".

You say "I prefer to say that sensations are not the kind of thing that has colour.", then how do you explain the relationship between the mind and its sensations.

I am a good deal more than the set of my sensations. — unenlightened

It may well be that you are a Substance Dualist, having the belief that the mind and body are fundamentally distinct kinds of substances. If so, what kind of substance do you think the mind is, and how does it causally affect the body, a different substance altogether.

But do you see the difficulty of your diagram, that recreates colours 'in the mind'; it would require someone to be looking at the mind, to see what colour things were in there. That is the recursion we really need to avoid — unenlightened

Yes, that someone is the person having the mind in the first place.

And the way to do it is to leave colours where they are, in leaves and flowers and stuff, and let all the 'mind-stuff' including sensations be colourless and featureless electrochemical shenanigans, or moving spirit, or some such. — unenlightened

If a sensation is colourless, then how do we know that objects in the world, such as leaves and flowers, have colours at all. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryI prefer to say that sensations are not the kind of thing that has colour. — unenlightened

It is normal to say "I have the sensation of green", as it is normal to say "I have a book"

But "I have a book" means that "I" and the "book" are independent of each other, in that the "book" exists independently of "me".

Grammatically, as "I" and the "book" are independent of each other, then it would follow that "I" and "the sensation of green" are independent of each other.

Yet this cannot be the case, as "I" am no more than the set of my sensations. My sensations are what comprise "me".

It would follow that it would be more correct to say that "I am the sensation of green".

This avoids the infinite regression problem which would happen if "I" am separate from my sensations, yet my sensations exist within "me". -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryBut if I were to ask you what colour the sensation of colour was, you might wonder what I meant — unenlightened

A large object is large. A circular object is circular. A green sensation is green.

As being circular is not independent of a circular object, being green is not independent of a green sensation.

Therefore, the sensation of green is green. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryIt seems to me that the sensation of colour has no colour; it takes place in the dark. — unenlightened

In my dreams, which take place in the dark, I can have the sensation of colour.

Whether in a dream or waking, if there is nothing to sense then there cannot be a sensation, ie, a sensation cannot be of nothing.

As a sensation cannot be of nothing, the sensation cannot be independent of what is being sensed, ie, the sensation is what is being sensed.

Therefore, if what is being sensed is colour, as the sensation is what is being sensed, then the sensation itself is colour. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryIn fact he does not even support indirect realism, consider PI 304, “The conclusion was only that nothing would serve just as well as a something about which nothing could be said.” An indirect realist would not say this. They would say that there are “somethings” and these somethings are private sensations and we have much to say. — Richard B

Wittgenstein is not saying that there is a "nothing". He is saying that there is a "something", but within the language game, this "something" drops out of consideration.

As regards "object and designation", the object is the intentional content, the private subjective feeling, such as pain and the designation is the public name used in a language game, such as the word "pain"

Wittgenstein in PI 304 writes that the sensation of pain is a definite "something" and attacks those who say that the sensation of pain is a "nothing". He writes that it is only within the context of a language game that this "something", this pain, drops out of consideration.

"But you will surely admit that there is a difference between pain-behaviour accompanied by pain and pain-behaviour without any pain?"—Admit it? What greater difference could there be?—"And yet you again and again reach the conclusion that the sensation itself is a nothing"—Not at all. It is not a something., but not a nothing either!"

Wittgenstein PI 304 continues that within the language game, as this "something", the object of pain, drops out of consideration, then "nothing" would serve just as well. This is obviously nonsense, because if there was "nothing" in the first place, then there wouldn't be anything to drop out of consideration. If there was "nothing" in the mind, there would be no language. In fact, there would be no humans as we know them.

"The conclusion was only that a nothing would serve just as well as a something about which nothing could be said. We have only rejected the grammar which tries to force itself on us here."

Wittgenstein continues in PI 304 that language doesn't function by directly linking object with designation, by directly linking the private sensation of pain with the public name of "pain", which happens to be the Direct Realist's position.

"The paradox disappears only if we make a radical break with the idea that language always functions in one way, always serves the same purpose: to convey thoughts—which may be about houses, pains, good and evil, or anything else you please."

Wittgenstein writes in PI 293 that language functions by publicly naming things in the world, and it may well be the case that everyone has a different private subjective feeling, a different "beetle" in their box.

"If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word "pain" means—must I not say the same of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly? Now someone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case!——Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.—Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box."

I agree that Wittgenstein studiously avoids taking any philosophical position, however, his Beetle in the Box analogy is a good argument against Direct Realism and for Indirect Realism. -

A Wittgenstein Commentarybut what can true color even mean here ? — plaque flag

Where does colour exist

I agree. It comes down to a matter of opinion.

The Direct Realist would say that as we directly see the world around us, things in the world, such as colours, are perceived immediately rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

The Indirect Realist would say that our conscious experience is not directly of the world itself, but is an internal representation of an external world. This external world is real and is the cause of our sensations, but as an effect does not need to be the same as the cause, what we sense is an effect that does not of necessity need to be of the same kind as its cause in the world.

The Direct Realist would therefore say that if we see a red object, then in the world there exists also a red object. The Indirect Realist would say that if we see a red object, all we can say is that our sensation has been caused by something in the world. But as an effect is not of necessity the same as its cause, then the cause in the world must remain unknown. In Kant's terms, a thing in itself.

As an Indirect Realist, I cannot know that colours don't exist in the world but my belief is that they don't.

Wittgenstein's Beetle in the Box supports Indirect Realism

Wittgenstein's support for the Beetle in the Box analogy indicatives his support for Indirect rather than Direct Realism.

Wittgenstein in PI 293 wrote about an unknown beetle:

Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.

If Direct Realism was correct, given a beetle in the external world, I would directly perceive this beetle. Other people would also directly perceive the same beetle. As everyone looking at the beetle would have the same intentional content, everyone would know everyone else's intentional content. Everyone would know that their private perception was the same as everyone else's, contradicting Wittgenstein's private language argument, and contradicting PI para 272 where he wrote that nobody knows another person's sensations:

The essential thing about private experience is really not that each person possesses his own exemplar, but that nobody knows whether other people also have this or something else. The assumption would thus be possible—though unverifiable—that one section of mankind had one sensation of red and another section another.

Wittgenstein's Beetle in the Box is an argument against Direct Realism. -

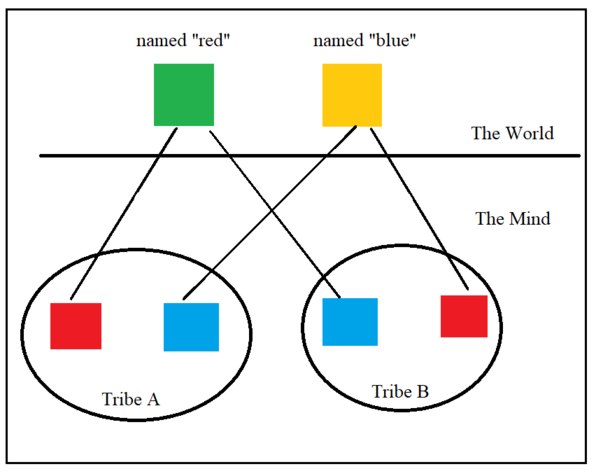

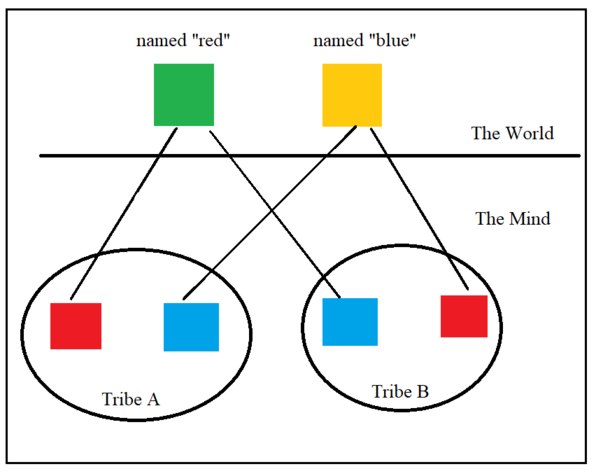

A Wittgenstein CommentaryFor simplicity sake let us assume we are in a world with just two colors, red and blue. In my tribe, we learned when we see a red object we call it “red” and when we see a blue object, we call it “blue”. One day we travel to an island and we meet another tribe that surprisingly has a very similar language like ours with the exception that when they see a red object they call it “blue” and when they see a blue object they call it “red”. — Richard B

In the world are two objects. One has been named "red" and the other has been named "blue". No-one knows the true colours of these two objects. However, let them be green and orange for the sake of argument.

For Tribe A to see a red object does not mean that the object they are seeing is red, it just means that they see the colour red when looking at the object named "red",

Similarly, for Tribe A to see a blue object does not mean that the object they are seeing is blue, it just means that they see the colour blue when looking at the object named "blue".

Similarly for Tribe B.

As you say, these two Tribes can still carry on a sensible conversation, because the objects have been named, regardless of any private subjective experiences. This is Wittgenstein's "Beetle in the Box". -

Sensational ConceptualityI think she can — plaque flag

If Mary can talk about not only the concept of colour but also what it feels like to perceive colour, then, in your own words, how would you describe your perception of the colour violet to a person who cannot see colours. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryThe nearsighted person sees the same ball as the colorblind person with 20/20 vision. And this is the same ball that the blind person can talk about. — plaque flag

I agree that Mary can talk about the concept of colour, ie "colour is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though colour is not an inherent property of matter, colour perception is related to an object's light absorption, reflection, emission spectra and interference"

But can Mary talk about what it feels like to perceive colour ? -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryYou talk of wavelengths a moment ago, and I presume you rely on the public inferential aspect of the concept. But it's hard to imagine how you could have a private sense of wavelengths without being immersed in a culture that uses this meaningful token in inferences (explanations.) — plaque flag

True. On the one hand, how can I have the private sense of things by description, such as democracy, the 1969 Moon landing, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Machu Picchu, wavelengths, atoms, Julius Caesar, etc. Such description can only be through language, and language requires being part of a society that uses language.

But on the other hand, I can have the private sense of things by acquaintance, such as feeling pain, smelling a rose, tasting coffee, hearing laughter and seeing a colour. Such acquaintance is independent of language, and doesn't require being part of a social group.

How is it possible to understand a wavelength when I only know it through description as "the distance between successive crests of a wave, especially points in a sound wave or electromagnetic wave."

Any whole that is only known by description can only become understandable if the parts are known by acquaintance.

First, as I already know by acquaintance the following parts - the distance between two things, the crest of a wave, a point and a sound - I can remove them from the description, leaving the unknown terms successive, especially and electromagnetic.

Successive is defined as following one another. Especially is defined as singling out one thing over all others. Electromagnetic is defined as relating electric currents and magnetic fields.

Second, as I already know by acquaintance the following parts - one thing following another, one thing taking prominence over another thing, the pain from touching a cattle electric fence and the movement of a compass needle in a magnetic field - I can remove them from the description.

In such as fashion, a whole only known by description may be reduced to component parts known by acquaintance. This allows me the private sense of wavelength, independent of language, and independent of any language-using society. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryWe learn what “red” is by being expose to red objects and judging similarly. What goes on inside is irrelevant to the meaning of the concept “red”. Private experiences of “blue” and “red”? No. — Richard B

I agree. But I think it is important to distinguish words in inverted colours such as "red" from those not in inverted commas, such as red. Otherwise it will be difficult to distinguish between what exists in language and what exists outside of language, whether in thought or the world.

For example, going back to Davidsons theory of meaning, whereby “‘Schnee ist weiss’ is true if and only if snow is white.”. "Schneee ist weiss" is within the object language, and snow is white is within the metalanguage, such that if and only if snow is white then the proposition "snow is white" is true.

Could it be that I have no experience of what we would call “color” but some other experience of a “private” kind? But what could that be and could it ever be communicated? — Richard B

I agree. When you see a "red" object your private subjective experience may be of the colour blue. But it is impossible for anyone other than yourself to know. But the fact that it is impossible to communicate to another person your private subjective experience, does not mean that you haven't had a private subjective experience.

This idea of “private meaning” is tempting but ultimately vacuous compared to where that idea of “meaning” has its life, among a group of language users talking about a shared reality. — Richard B

If you had no "private meaning", if you never had any private subjective experiences, if you never felt pain, saw a colour, smelt a rose, tasted coffee or heard laughter, then one could say that this would be a vacuous life. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryNietzsche in other passages gives Kant hell for making the real world (this one) an illusion. — plaque flag

However, one also reads in the Edinburgh Research Archive that Nietzsche was probably an anti-realist, whereby any external reality is hypothetical and not assumed.

Interpretations of Friedrich Nietzsche often suggest that he is some form of anti-realist, i.e. he does not affirm objective scientific truth or understanding of the world. Nietzsche advocates a viewpoint known as perspectivism, which may seem to cement this anti-realist interpretation, insofar as it emphasises the perspectival nature of understanding. Similarly, Justin Remhof interprets Nietzsche as an object constructivist, i.e. that objects within the world are constructed by human concepts, and this also seems to align neatly with anti-realist interpretations. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryI think the intentional concept has to include the public structuralist aspect of meaning, but that their can be a private founded aspect of meaning made possible by this public aspect. — plaque flag

Let's use the example in Wittgenstein's PI 1 of the colour red.

In the world is an object emitting a wavelength of 700 nm that society has named "red".

Bertrand's private mental image is unknown to us, but suppose when he sees an object emitting a wavelength of 700 nm his private mental image is of green. Similarly, Russell's private mental image is also unknown to us, but suppose when he sees an object emitting a wavelength of 700 nm his private mental image is of blue.

For both Bertrand and Russell, when seeing a wavelength of 700nm, there is a private meaning and a public meaning. For Bertrand, the private meaning is experiencing an intentional content of green and the public meaning is having seen a colour named "red". For Russell, the private meaning is experiencing an intentional content of blue, and the public meaning is having seen a colour named "red".

The private meaning is associated with the public meaning, but the private meaning is not included within the public meaning.

It is the same with Aristotle's Categories, where the categories may be associated with each other even though independent of each other. For example, in the sentence "there are four rocks", where "four" is quantity and rocks is substance.

Private meaning is not made possible by public meaning. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryLikewise, the beetle-in the box argument wasn't made to deny the semantic importance of intentional content, but to stress how social customs, such as the custom of physical language, have evolved to facilitate the expression of intentional content. — sime

As I understand the "Beetle in the Box" - in the world, suppose there is something that has been named by society a "beetle".

When looking at this "beetle", Bertrand actually has the private mental image of an ant, and Russell has the private mental image of a bee. Bertrand can never know Russell's private mental image, and vice versa.

Yet both Bertrand and Russell can have a sensible conversation about "beetles", even if their intentional contents, their private mental images, are different.

Within the language game, private mental images drop out of consideration as irrelevant. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryIn my view, the scientific image is valued because it describes this world and not something hidden under or behind it. — plaque flag

The language of science also has metaphorical value

An interesting topic that leads into the nature of language. It can be argued that language, including the language of science, is more metaphorical rather than literal.

The scientific image is also valued not because it is able to directly describe the reality of the world but because it allows humans a metaphorical understanding of what cannot be literally understood through the use of metaphor.

Metaphors are commonly used in science, such as: evolution by natural selection, F = ma, the wave theory of light, DNA is the code of life, the genome is the book of life, gravity, dendritic branches, Maxwell's Demon, Schrödinger’s cat, Einstein’s twins, greenhouse gas, the battle against cancer, faith in a hypothesis, the miracle of consciousness, the gift of understanding, the laws of physics, the language of mathematics, deserving an effective mathematics, etc.

Andrew May in Metaphors in Science 2000 makes a strong point that even Newton's second law is a metaphor

"In his article on the use of metaphors in physics (November issue, page 17), Robert P Crease describes several interesting trees but fails to notice the wood all around him. What is a scientific theory if not a grand metaphor for the real world it aims to describe? Theories are generally formulated in mathematical terms, and it is difficult to see how it could be argued that, for example, F = ma "is" the motion of an object in any literal sense. Scientific metaphors possess uniquely powerful descriptive and predictive potential, but they are metaphors nonetheless. If scientific theories were as real as the world they describe, they would not change with time (which they do, occasionally). I would even go so far as to suggest that an equation like F = ma is a culturally specific metaphor, in that it can only have meaning in a society that practices mathematical quantification in the way that ours does. Before I'm dismissed as a loopy radical, I should point out that I'm a professional physicist who has been using mathematical metaphors to describe the real world for the last twenty years!"

As Nietzsche wrote “We believe that when we speak of trees, colours, snows, and flowers, we have knowledge of the things themselves, and yet we possess only metaphors of things which in no way correspond to the original entities.” -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryWithin this familiar (life-)world, we enrich our knowledge of everyday entities by adding scientific entities which are inferentially entangled and semantically dependent on those everyday entities — plaque flag

A nice, almost poetic explanation of Indirect Realism.

I'd say we learn how to conceptualize and discuss a pain and a color that is just there, mostly nonconceptually, as a kind of overflow of any mere intending or labeling of it. — plaque flag

In Kant's terms, we conceptualize our intuitions. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryLately it looks to me that structuralist approaches to meaning (meaning as use, perhaps as inferential role) are illuminating but maybe leave something out — plaque flag

If Structuralism focuses on the way that human experience and behaviour is determined by various structures external to the individual, then it is suffers from the same problem as Behaviourism.

I don't learn how to feel pain as a result of the social world I may happen to live in, but suffer pain, am able to see the colour red, feel anger, etc because of Innatism, in that the mind is born with already-formed ideas, knowledge, and beliefs.

Meaning may be use within a form of life, as Wittgenstein said, but meaning is also in part determined by the fact that we are not born as blank slates. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryYes, Rouse was heavily influenced by Wittgenstein. — Joshs

It seems that the post-modernism of the French post-structuralists in the 1970's can also be traced back to the Wittgenstein's investigation into the limits of language and language in the 1950's. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryJoseph Rouse — Joshs

There are similarities between Rouse's postmodern view that we can never get outside our language and Wittgenstein's view, as a possible anti-realist or linguistic idealist, that the meaning of a word is determined by the language itself rather than any transcendent reality.

Wittgenstein wrote in PI 43 "For a large class of cases—though not for all—in which we employ the word "meaning" it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language."

As Joseph Rouse wrote about a postmodern view of science - "we can never get outside our language, experience, or methods to assess how well they correspond to a transcendent reality" -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryThere are other ways of thinking about the relation between mind and world than in terms of the binaries realist vs anti-realist or empiricist vs idealist. — Joshs

What other ways are you thinking of, of how the subjective mind of colours, pains, fears and hopes relates to the objective world of rocks, mountains, supernova and gravity. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryFurthermore, the existence of the particulars is neither strictly in the mind nor in the world. It is in the relational practices that make linguistic meaning dependent on the enacting of material configurations through our engagement with the social and non-human world. — Joshs

Wittgenstein writes that the meaning of a word exists in the relation between the mind and the world.

PI 43. For a large class of cases—though not for all—in which we employ the word "meaning" it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.

Wittgenstein may well be either an anti-realist or idealist

From the IEP article on Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889—1951)

Wittgenstein’s place in the debate about philosophical Realism and Anti-Realism is an interesting one. His emphasis on language and human behaviour, practices, etc. makes him a prime candidate for Anti-Realism in many people’s eyes. He has even been accused of linguistic idealism, the idea that language is the ultimate reality.

Anti-realism is a belief opposed to Realism, which contends that there are things that exist mind-independently.

If Wittgenstein is in fact either an anti-realist or idealist, where there is no mind-independent world, then as for Wittgenstein the meaning of a word is in its relation between mind and world, and as for Wittgenstein the world exists in the mind, then it follows that for Wittgenstein, the meaning of a word must also exist solely in the mind. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryWhereas my interest is in showing that things which look the same are really different — Fooloso4

As Wittgenstein said, board games and card games may not have anything in common, but they do have similarities, which he calls "family resemblances".

PI 66. Consider for example the proceedings that we call "games". I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all?—Don't say: "There must be something common, or they would not be called 'games' "—but look and see whether there is anything common to all.—For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that.

PI 67. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than "family resemblances"; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way.— And I shall say: 'games' form a family. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryConcepts in the mind pick out categories in the world — javi2541997

Given that concepts in the mind pick out categories in the world, the question is, which came first, the concept in the mind or the category in the world.

Either i) first there are concepts in the mind which then pick out categories in the world or ii) concepts are created in the mind by picking out categories in the world.

Which better explains the world, Innatism or Behaviourism.

For the Innatist, we are born with certain concepts, and then use these concepts to discover categories in the world, such as the category table. For the Behaviourist, there are categories in the world that we discover in order to create concepts in the mind, such as the concept table

Where does the essence of the table exist - as innate concepts in the mind or Platonic Forms in the world.

Where do family resemblances exist - in the mind or in the world. -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryMany human concepts family resemblance categories rather than classical concepts (Aristotelian). — javi2541997

Wittgenstein's and Aristotle's categories have different purposes, in that they are trying to achieve different things.

Aristotle's categories are trying to divide the world into features that are independent of each other, for example, organic vs non-organic, where something exists vs when it existed, the properties of an object vs what the object can do using these properties, etc.

Wittgenstein on the other hand is concerned with finding those words within language that may not be thought as independent of each other, such that chess and football fall within the same category of game.

Aristotle would not have an interest in the difference between chess and football as such difference does not contribute to our understanding of how the word is divided into independent categories, whereas Wittgenstein would have an interest in the difference as they are both part of the same category of "game".

Aristotle is using categories to discover differences, whereas Wittgenstein is using categories to discover similarities. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?The question is "do the noumena exist and do the noumena cause appearances?" Not do "appearances have causes?" — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree that when sleeping and dreaming, appearances have not been directly caused by things external to the mind. The question is that when awake, is it also the case that appearances have not been caused by things external to the mind. An Idealist would say yes, a Realist would say no.

Regarding Idealism, it is either the solipsism of my mind or Berkeley's mind of God. I exclude the first possibility as I doubt I wrote War and Peace. I exclude the second possibility because of Occam's razor, in that there being no God is a simpler explanation than there being one.

This leaves Realism, in that there is a world outside the mind, and appearances can be caused by things external to the mind.

It's a false dichotomy to claim that rejecting noumena means rejecting the reality external world. — Count Timothy von Icarus

If it is possible for there to be an external world without things in themselves, what would make up this world ?

To say the noumena IS accessible in that is must be the cause of appearances is to beg the question. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think a Direct Realist would say that things in themselves are directly accessible, whereas an Indirect Realist would say that they are only indirectly accessible. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Nevertheless, isn't Kant making an assumption by saying there are "things in themselves"? This includes plurality, how do we know if there is such a thing? — Manuel

For two reasons, common sense and textual.

Common sense

What kinds of objects are things in themselves.

From A29 of CPR: For in this case that which is originally itself only appearance, e.g., a rose, counts in an empirical sense as a thing in itself, which yet can appear different to every eye in regard to colour.

From A272: Of course, if I know a drop of water as a thing in itself according to all of its inner determinations, I cannot let any one drop count as different from another if the entire concept of the former is identical with that of the latter.

By common sense, does anyone not believe in the existence of roses, drops of water, houses, camels, trucks, etc. Would anyone crossing a busy road and seeing a truck bearing down on them actually think that the truck, the thing in itself, doesn't exist in reality but only as a figment of their imagination. Wouldn't everyone make sure they quickly got out of the way. Doesn't everyone believe in that things in themselves exist independently of their own thoughts of them.

Would Kant have not worked at the University of Königsberg for 15 years if he thought that the thing in itself, the University, only existed in his imagination and not in reality.

Can anyone argue from common sense that Kant was not a Realist.

He was clearly not a Direct Realist, as the Direct Realist believes they have direct and immediate knowledge of the thing in itself.

His philosophy, as @mww writes "Matter, as such, cannot have a name, which is a representation derived from the synthesis of conceptions, hence given from thought, not sensation" is that of Indirect Realism, the view of perception that subjects do not experience the external world as it really is, but perceive it through the lens of a conceptual framework.

Textual evidence for the existence of the thing in itself

Kant makes numerous statement against the charge of Idealism.

In the CPR Anticipations of Perception, sensation can be understood both as stemming from the object of experience as well as the thing in itself. This duality may only be understood if the transcendental is distinguished from the empirical. Kant's Theory of Affection allows for two different explanations, though together make a coherent whole account of human knowledge.

It would be a mistake to conclude that because a thing in itself remains indeterminate it cannot exist. Common sense tells us that there is something behind an appearance, even if we don't know what it is.

Kant wrote in A536 of the CPR that appearances must have grounds that are not appearances.

If ... appearances are not taken for more than they actually are; if they are viewed not as things in themselves, but merely as representations, connected according to empirical laws, they must themselves have grounds which are not appearances. The effects of such an intelligible cause appear, and accordingly can be determined through other appearances, but its causality is not so determined. While the effects are to be found in the series of empirical conditions, the intelligible cause, together with its causality, is outside the series. Thus the effect may be regarded as free in respect of its intelligible cause, and at the same time in respect of appearances as resulting from them according to the necessity of nature.

We know that objects of experience, although they are mere appearances, are given to us. If the appearance has not been generated by the knowing subject, then an external cause must exist, even if the external cause is unknowable. The thing in itself allows for the very possibility of appearance.

There are many passages in the Fourth Paralogism where the thing in itself is declared as the cause of appearance, and even in the Second Analogy, the thing in itself is described as the source of affection.

Summary

Kant is clearly a Realist, and in today's terms an Indirect Realist. Kant's Theory of Affection

may be read as not only that sensation stems from the object of appearance but also from the thing in itself, not a contradictory position, but two parts of a coherent whole. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Paul Davies............by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers — Quixodian

Science tells us the Universe began about 13.8 billion years ago, and life began on Earth about 3.8 billion years ago.

Is Davies saying that as the Universe can only exist if there are observers to observe it, life must have begun 13.8 billion years ago. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Don’t be a pillock — Jamal

Pillock, a stupid person. I will have to remember to use that term in the future on the Forum. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?I was just correcting your anglocentric assumptions. — Jamal

In what way is my belief that humans across the world subjectively perceive colour in a similar way Anglo-centric ? -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Note that this is just cultural. Russians have no word for blue*. Light and dark blue, goluboy and siniy, are seen as different colours, as different as red and orange. — Jamal

I can only speak from general knowledge, but whilst I agree that colour has different linguistic and social meaning between different cultures, I don't agree that humans within different cultures would not have the same subjective perception of different wavelengths.

The Wikipedia articles on Color and Color Terms writes that whilst English has 11 basic colour terms, other languages have between 2 and 12. How the spectrum is divided into distinct colours linguistically is a matter of culture and historical contingency. Colours have different associations in different countries and cultures.

Even though a Russian and a Scot have different linguistic terms for colours, if you showed the Scot and the Russian the three wavelengths of 420nm, 470nm and 700nm, my belief is that they would both agree that there was a common feature between 420nm and 470nm but not between 420nm and 700nm

IE, colour perception is not just cultural, it is human, common across different cultures. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Colour is not wavelength — Metaphysician Undercover

If what I've read on this is accurate the human can distinguish about 10 million colours, although for simplicity we don't have many different names for them. — Janus

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. A typical human eye will respond to wavelengths from about 380 to about 750 nm The average number of colours we can distinguish is around a million.

English has 11 basic colour terms: black, white, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, orange, pink, purple, and grey.

It is part a problem of terminology. On the one hand, a wavelength of 420nm is a different colour to a wavelength of 470nm, but on the other hand, even though we can distinguish them, we perceive them both as the single colour blue.

The interesting question is how we can perceive the wavelengths of 420nm and 470nm as two different things yet at the same time perceive them as a single thing. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Kant sometimes oscillates between the "thing-in-itself" and "things in themselves", and these, obviously, are different in an important respect, in that one presupposes individuation, the other does not. — Manuel

It seems "things in themselves" refer to several objects of experience, whilst "thing in itself" refers to one object of experience.

From the CPR:

B xxvi Yet the reservation must also be well noted, that even if we cannot cognize these same objects as things in themselves, we at least must be able to think them as things in themselves.

A30 For in this case that which is originally itself only appearance, e.g., a rose, counts in an empirical sense as a thing in itself, which yet can appear different to every eye in regard to colour.

From the SEP article on Kant's Transcendental Idealism, Prauss (1974) notes that, in most cases, Kant uses the expression “Dinge an sich selbst” rather than the shorter form “Dinge an sich”. He argues that “an sich selbst” functions as an adverb to modify an implicit attitude verb like “to consider”. He concludes that the dominant use of these expressions is as a short-hand for “things considered as they are in themselves”

I guess the whole point is that we don't know that there are things in themselves, only that we believe that there are. The "selbst" indicates a mental attitude to something rather than the physical state of something. -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Do we have in mind noumenon in a negative sense or in a positive sense? — Manuel

Although Kant distinguished between positive noumena and negative noumena, as he didn't think positive noumena were possible, because they would require intellectual knowledge of a non-sensible intuition, the term noumena is assumed to mean a negative noumena, aka thing-in-itself, aka Dinge an sich selbst . -

What is the "referent" for the term "noumenon"?Also: being a realist does not preclude being an idealist — Count Timothy von Icarus

It depends what is being meant by realism and idealism. It comes down to definition, which are difficult to pin down, especially when there was even a thread on the Forum titled "Definitions have no place in philosophy". The SEP articles on Idealism and Realism are a start.

===============================================================================

Dorrien: Kant postulated a self-sufficient noumenal realm set apart from everything belonging to the phenomenal realm — Count Timothy von Icarus

A sensible acknowledgement that for the 10 billion years before life began on Earth, there was possibly no phenomenal realm.

===============================================================================

Dorrien: Kant’s Platonism, however, stood in the way of dealing with anything real — Count Timothy von Icarus

In another passage Hamann attacks Kant for elevating Reason into a universal Platonic ideal rather than being something grounded in a specific language and cultural context. An unwarranted criticism, in that a philosopher should not to be forced to make judgements unduly swayed by short term pressures from the particular society that they happen to live in.

===============================================================================

Kant realized that his critics would say the same thing about the thing-in-itself, but he needed the idea of the noumenon to account for the given manifold and the ground of moral freedom. The idea of a thing-in-itself that is not a thing of the senses is not contradictory, he assured — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is still a problem that Indirect and Direct Realism grapples with 200 years after Kant's death.

===============================================================================

Like Fichte, Hegel wants to find out how basic categories have to be understood, not just how they have in fact been understood. This can only be discovered, he believes, if we demonstrate which categories are inherent in thought as such, and we can only do this if we allow pure thought to determine itself—and so to generate its own determinations—“before our very eyes” — Count Timothy von Icarus

There is no problem of self-reference in Kant. It is not the case that thoughts can only be about thoughts.

For Kant, we think about objects of sensible intuition using the categories. The category doesn't determine what particular object is being thought about, although it is true that the categories limit what particular objects can be thought about.

It is true that the fact that I have the ability to see the colours red and green but not the colour ultra-violet does limit me in which colours I can see, but it does allow me to distinguish between the colours (of sensible intuition) that I am able to see.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum