-

The ineffableAnd if you are defending a physicalist view about the world, then the thesis is just untenable, unless you can explain epistemic connectivity between brains and objects in a physicalist setting with out abandoning physicalism itself. — Constance

Form and content, brains and minds

Is the mind and brain a Cartesian duality or a phenomenological unity. What is the relationship between the brain as form and the mind as content. If a Cartesian duality, how can the form access the content. If a phenomenological unity, how can the form be the content.

Protopanpsychism as the link between the form of the brain and the content of the mind

Consciousness is the hard problem of science. Whether consciousness exists outside the brain as some ethereal soul or spirit or can be explained within physicalism as an emergence from the complexity of neurons and their connections within the brain, protopanpsychism is not the belief that elemental particles are conscious, rather that they have the potential for consciousness that only emerges when elemental particles are combined in some particular way.

As an analogy with gravity, the property of movement cannot be discovered in a single object isolated from all other objects, but may only be observed when two objects or more are in proximity. In a sense, the single isolated object has the potential for movement, but doesn't have the property of movement. The property of movement emerges when two or more objects are in proximity with each other.

Similarly, the property of consciousness could never be discovered by science or any other means by observing a single neuron, yet the property of consciousness emerges when more than one neurons are combined in a particular way.

Protopanpsychism breaks Cartesian dualism by enabling both the brain and the mind to come under the single umbrella of physicalism. The content of the brain and the conscious mind emerges from the form of the physical brain.

If the mind and brain are two aspects of the same thing, and are part of a physicalist world, then this explains the epistemic connectivity between mind and brain.

Aristotle and the link between form and content

Aristotle's "four causes" were i) material cause , ie the bronze, ii) the formal cause, ie the statue of Hercules, iii) the efficient cause, ie, the sculptor and iv) the final cause , ie, the purpose of honouring Hercules. The formal cause is the form, the final cause is the content.

For man-made objects, the final cause is not problematic, in that the maker of the statue has made the decision, but for natural objects, purpose may be debated. What purpose do mountains serve, what purpose do humans serve, what is the purpose of anything.

Aristotle denied that purpose came from a divine maker, but rather that purpose was immanent in nature itself . IE, the purpose whether of mountains or humans existed within their very form, ie, content is form.

Purpose necessitates a holistic approach. As Aristotle wrote "we must think that a discussion of nature is about the composition and being as a whole, not about parts that can never occur in separation from the being they belong to". As Frege wrote in 1884, "Only in the context of sentence does a word have a meaning’. Frege's principle establishes contextualism. Individual words have no meaning or value unless they are understood within the context of a sentence, a reaction against the atomization of meaning.

Teleology is the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise, in that the purpose of humankind has been determined by neither something in the past nor something in the future, but by the existent present. A change in form inevitably results in a change of purpose. As Jonathan Lear wrote " "real purposefulness requires that the end somehow govern the process along the way to its own realization - it is not, strictly speaking, the end specified as such that is operating from the start: it is form that directs the process of its own development from potentiality to actuality".

The purpose of something in the world, its content, may be said to be determined by the nature of its essence, in other words, its form.

Heidegger and the link between form and content

The value of a Derain is in its aesthetic of representations. The form holds both the aesthetic and the representational content.

Heidegger wrote The Origins of the Work of Art between 1935 and 1960, whereby the "origin" of an artwork is that from which and by which something is what it is and as it is, its essence. The artwork has a mode of being that it is the artwork itself. The origin of an artwork is the artwork itself. An artist may have caused the artwork, but it is the artwork that has caused the artist. The artwork determines what the artwork will be, not the artist. The artist is just a facilitator. Art as the mode of being makes both the artist and artwork ontologically possible. Art unfolds the artwork. The artwork has a life of its own, independent of any maker. Heidegger's phenomenology emphasises the artwork as "Being", as he said "back to the things themselves".

On the one hand, to appreciate art one must start with an understanding of what art is, yet on the other hand we can only appreciate art from the work itself. A paradox described by Plato as "A man cannot try to discover either what he knows or what he does not know. He would seek what he knows, for since he knows it there is no need of the inquiry, nor what he does not know, for in that case he does not even know what he is to look for". This is a circle only broken by an innate and a priori knowledge of Kantian pure and empirical sensible intuitions, of space, time and the categories of quantity, quality, relation, modality.

An artwork has Being and is its own Origin, yet we can understand art from our innate and a priori knowledge of aesthetics and representation that precedes ant experience of art. We can understand the aesthetic form and representational content as a single unity of apperception as a holistic synthesis of form and content.

But on the issue of ineffability, I also think there is nothing precluded in this regarding novel and extraordinary experiences in which there is an intimation of deeper, more profound insights about our Being here. — Constance

Language is metaphor

In language is the syntax of form and the semantics of content. Language is a set of words. A word is a physical object that exists in the world, as much as a mountain exists in the world.

Words refer to, represent, are linked to, corresponds with either another object in the world or a private subjective experience, such that "mountain" is linked to mountain or "pain" is linked to pain.

A metaphor directly refers to one thing by mentioning another and asserts that what are being compared are identical and clarifies similarities between two different ideas.

As mountain is being referred to by mentioning "mountain", as pain is being referred to by mentioning "pain", as it is asserted that the reference of "mountain" is identical with mountain, as it is asserted that the reference of "pain" is identical with pain, as the similarities between "mountain" and mountain, "pain" and pain are being clarified, then the linkage between a word and what it refers to fulfil all the requirements of a metaphor.

The word as an object is different to what it refers, meaning that any linkage between the word and to what it refers is metaphorical. As language is metaphorical, all our understanding through language is metaphorical: evolution by natural selection, F = ma, the wave theory of light, DNA is the code of life, the genome is the book of life, gravity, dendritic branches, Maxwell's Demon, Schrödinger’s cat, Einstein’s twins, greenhouse gas, the battle against cancer, faith in a hypothesis, the miracle of consciousness, the gift of understanding, the laws of physics, the language of mathematics, deserving an effective mathematics, etc

Words are symbols that refer metaphorically. As a metaphorical link can be created between any known object in the world and a word or any known private subjective experience and a word, any known object in the world or known private subjective experience can be expressed in language, meaning that in language, nothing that is known is ineffable.

Conclusion

As language is metaphorical, and as every known object in the world or known private subjective experience can be expressed in metaphorical terms, everything that is known can be said, whether concrete concepts such as mountain, abstract concepts such as pain, non-existents such as “The present King of France is bald.”, negative existentials such as “Unicorns don’t exist.”, identities such as “Superman is Clark Kent.” or substitutions such as “Taylor believes that Superman is 6 feet tall.”

Only that which is unknown cannot be put into words. Only that which is unknown is ineffable. If it is known, it can be put into words and is expressible. -

The ineffableRussellA adopts a referential theory of meaning. — Banno

In the referential theory of meaning, words mean what they refer to in the world. Words are like labels attached to things existing in the world, in that the word "mountain" refers to the object mountain.

However, as I see it, not only is a mountain an object in the world, but also the word "mountain" is an object in the world (setting aside exactly what objects are).

During (metaphorical) public performative acts establishing meaning, any set of objects in the world may be linked. For example, "mountain" may be linked to mountain, "mountain" may be linked to "awesome" and mountain may be linked to river.

As the referential theory of meaning only allows words such as "mountain" to be linked with objects such as mountain, because my theory of meaning allows not only words such as "mountain" to be linked to other words such as "awesome" but also objects such as mountain to be linked to other objects such as river, I don't adopt the referential theory of meaning.

One advantage of my theory of meaning is that it allows the word "horse" to be linked with the phrase "horn projecting from its forehead", overcoming one of Russell's and Frege's objections against the referential theory. -

The ineffableWhat are you tryin to justify? — Constance

I believe that there are limits to what language can explain about the word because of the intellectual limits of the human brain, in that language cannot transcend the mind. Language doesn't have a power that is not given to it by the mind.

You will have to turn to phenomenology, which is about the Totality of our existence, and not just an aggregate of localized arguments that is found in analytic thinking. — Constance

Perhaps neither the anti-reductionist Phenomenology nor the reductionist Cartesian method can be used by themselves. Both lead to problems. The Cartesian method suffers from treating the world as a set of objects interacting with each other. Phenomenology suffers from rejecting rationalism, relying on an intuitive grasp of knowledge, and free of intellectualising.

Taking the analogy of art, a complete understanding of a Derain requires both an intellectualism of the objects represented within the painting and an intuitive grasp of the aesthetic artistic whole. IE, a synthesis of both the Cartesian and the Phenomenologist. -

The ineffableAre you making a claim here? — Richard B

Yes, I was making a claim that our private subjective concepts of a particular word cannot be the same, in that it is impossible for them to be the same, although they may be similar.

I can never know my claim is true, as I cannot put myself into someone else's mind. I believe my claim is true from observations of other people's behaviour, but I can never know. It is an inference.

On the other hand, how would it be possible for anyone to know that their private subjective concept of a particular word was the same and not just similar to someone else's? -

The ineffablePhysical limitations of the brain; what an interesting assumption — Constance

If there were no intellectual limitations to the brain, I could have understood Tarski's Semantic Theory of Truth by now.

Hemmingway likely never intended any allegorical reading of his work — Constance

The Old Man and the Sea as Christian allegory

This chasm, how do you know about it? — Constance

If knowing is a justified true belief, I don't know there is a chasm. I believe there is and I can justify my belief that there is. I infer there is, but I don't know there is as I don't know whether or not my belief is true. -

The ineffableThis is what many folk (perhaps ↪Constance?) think analytic philosophy suggests. That could not be further from the truth. From at least Russell's theory of descriptions, philosophy has whole-heartedly rejected this idea, and with good reason: If "mountain" is a label to a set of private subjective experiences in each of us, we are never, when discussing mountains, talking about the same thing. But meaning is public. Better to talk of use. — Banno

Words are public yet meaning can be private

A word is a public object

Words are public objects. They only have a use because they are public objects that enable communication between individuals. They exist as public objects in speech and text. As objects, they physically exist in the same way as apples, mountains, etc. I can observe the word mountain in the world as can everyone else. The value of language is that the words it uses are public.

The meaning of words is inferential

Public words are given public meaning in public performative acts. As noted by Davidson, T-sentences are laws of empirical theory. Someone says "snow is white" and points to snow is white. Knowledge of language is extensional to the words themselves. Someone points to a mountain and says "mountain" several times. From Hume's concept of constant conjunction, the observer may infer that "mountain" means mountain. The meaning of words must always remain inferential, in that even if someone points to a mountain and says "mountain" one hundred times, the hundredth and first time they may point to a mountain and say "hill"

Yet my concept of "mountain" cannot be the same as anyone else's. My concept has developed over a lifetime of particular personal experiences, as is true for everyone else. A Tanzanian's concept of "mountain" must be different to an Italian's concept of "mountain". My concept of "mountain" is private and subjective, inaccessible to anyone else in the same way that my experience of the colour red is private, subjective and inaccessible to anyone else.

But it is also true that society has determined that "mountain" means "an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock." The meaning of "mountain" has been expressed in a set of other words, all of which as words are public objects observable by different individuals.

Yet the same problem arises, in that my concept of each of these words cannot be the same as anyone else's. For example, a Tanzanian's concept of "steep" must be different to an Italians' concept of "steep". What "steep" means to me must be different to what it means to anyone else

Ultimately, I learnt the meaning of new words inferentially, which is a private and subjective experience.

It is true that most individuals within a society have similar concepts for the same public words, but then again, this is only an inference. An inference is a private and subjective belief. A belief that I can justify, but can never know to be true.

Communication uses public words

However, the fact that the meaning of any pubic word is private and subjective is no barrier to communication between people. Communication is about the public word, not the private meaning.

Taking a simpler example, assume there are five red apples on the table, publicly labelled in a prior performative act "five", "red" and "apples". My private subjective experience of "red" may be green, your private subjective experience of "red" may be blue, but our private subjective experience is irrelevant in the language game of being asked to pass over the "red" apple. Even though I experience green, I will pass over the "red" apple. Even though you experience blue, you will also pass over the "red" apple. Our private subjective experiences "drop out" of the act of passing over the "red" apples.

"Red" means the public colour of the apple, even if it privately means green to me and blue to you. Words only have meaning if they can be used to change the state of the world, ie, meaning as use.

Bertrand Russell's Theory of Descriptions

Meaning as public

Bertrand Russell wrote On Denoting, which later became the basis for Russell's "Descriptivism", whereby proper names are really "definite descriptions". Kripke described Russell's Theory of Descriptions in order to critique it, which I believe would be as follows:

1) When I hear the name "mountain", I believe that "mountain" is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock.

2) I believe that this set of properties picks out "mountain" uniquely.

3) If most of the properties are satisfied by one unique object then "mountain" refers to mountain

4) If most of the properties are not satisfied by one unique object then "mountain" doesn't refer to mountain

5) I learn that "mountain" has the properties elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock.

6) Knowing that "mountain" has these properties, when observing these properties, I know that it is a "mountain"

The word "mountain" describes the properties elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock, similarly "steep" denotes steep, "elevated" denotes elevated etc. "Mountain" means an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock, "steep" means steep, "elevated" means elevated, etc

All these things exist as physical objects in the world. Words such as "mountain" physically exists, objects such as mountains physically exist. They all exist in a public space, observable by any individual. Meaning has been established in a public performative act, as Kripke says by a christening, as Davidson says by pointing. Society has determined that "mountain" means mountain. In this sense meaning is public.

Meaning as private

Yet language couldn't exist without the mind of an observer of such a public world. Neither "mountain" nor mountain have meaning independent of an observer. What "mountain" or mountain means to me is unique to me, private and subjective to me, not accessible to anyone else but me. But as can be seen with the example of the five red apples, private subjective meaning is no barrier to public communication.

Conclusion

So which is correct. Is meaning public or private. In a sense both, in that in a public performative act a mountain in being christened a "mountain" establishes that "mountain" means mountain. And yet meaning does not exist independent of any sentient observer, whereby both "mountain" and mountain mean something different to every different individual. -

The ineffableBut this just puts the burden on the term "objectify" — Constance

Words objectify what they refer to

A word such as "mountain" is a physical thing as much as a mountain is a physical thing. The "mountain" is as much an object as the mountain. Somehow, "mountain" means mountain, is linked with mountain and corresponds with mountain. The "mountain" came after the mountain, in that "mountain" has only existed for less than 100,000 years whereas mountain has existed for at least 4 billion years.

As the "mountain" came after the mountain, as the "mountain" is an object, as the "mountain" somehow relates to the mountain, in that sense, the "mountain" has objectified the mountain.

Sartre had this concept of radical contingency: when we encounter the world, the world radically exceeds what language can — Constance

The world exceeds our ability to explain it

The limits of our concepts

I have learnt the concept of "mountain". On arriving in Zermatt for the first time, the reality of mountains far exceeds my concept, but on leaving, my concept will probably have changed, hopefully giving me a better understand of the nature of mountains. Yet no matter how much my understanding improves, my understanding of the true nature of mountains will always remain insignificant. Metaphorically, my understanding of a mountain will be that of a horse's understanding of the allegories in Hemingway's The Old Man and The Sea, not because of a lack of trying, but because of the natural limitations of its brain. I am sure that if a superintelligent and knowledgeable alien race arrived on Earth, and tried to explain the true nature of time and space, we wouldn't have the foggiest idea of what they were saying. Not because we didn't want to know, but because of the physical limitations of our brain.

Sartre and existence

If knowledge and understanding is limited by the inherent structure of our brain, and similarly our use of language, then it follows that there will be a natural limit in our understanding of the reason for our own existence. In Sartre's terms, the "for-itself" may exist without ever finding a reason for its own existence. Existing without any justification or explanation, which is, for Sartre, a tragic existence. Without an explanation for our own existence, to exist is to simply be here. One experiences a groundlessness, existing without ever knowing why. An existence that is accidental and subject to chance, We may search for meaning, but ultimately there is no meaning in "being-in-itself", as there is no meaning in the world waiting to be discovered.

The limits of language

Language is a product of the brain, and is therefore limited by the brain. If our understanding is limited by the brain, then what can be achieved by language must also be limited. Language cannot be used to escape the "for-itself". Language can only mirror our limited understanding of the world, a world that radically exceeds that which can be explained in language. The chasm between the world and what can be explained in language is insurmountable because of the limited nature of the brain

Language as a mirror of the intellect is limited in its description of the world by the limits of the intellect, which is limited by the physical structure of the brain. Consequently, our understanding of the world is more about how the world appears to us, rather than how it actually is. -

The ineffableIs language so inhibitive? — Constance

Words objectify what they are referring to. "Morality" identifies morality as a thing, "mountain" identifies mountain as a thing. This is how language works, and this is how we can use language to communicate

But as you say "If God were actually God, and this was intimated to you in some powerful intimation of eternity and rapture that was intuitively off the scales, would language really care at all?" No, language wouldn't care. I don't need language to have the private subjective experience of morality or a mountain. Humans experienced these things pre-language.

On the one hand, language imposes restrictions on what can be said. My understanding of a "mountain", my concept of "mountain" has grown over a lifetime of individual experiences, and is certainly different to your understanding and concept of "mountain", built up over a lifetime of very different experiences. Yet we both use the same word when using language to communicate, seemingly inhibiting what we can say.

For me, the word "mountain" is a label to a set of private subjective experiences. A single word can label a set of experiences. A single word is an object that refers to a set of experiences. When I think of a word as a label I am thinking not of a single thing but of a set of experiences linked to that word. When I think of a word I am thinking of the set of things that that word refers to

When we use the same word in conversation, we will be thinking of very different sets of experiences, but providing we have agreed beforehand with the definition that "A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock.", although our language may restrict what can be said, it doesn't restrict what we can think.

A word can be a label for a complex set of objects, facts, events, feelings, etc, but when I think of a label such as "morality", "mountain" etc, I am not thinking of the label but the set of things that the label is attached to. The fact that a label can be attached to a set of things means that there is some similarity between the things, it does not mean that the things cannot also be different.

As Elizabeth Barrett Browning put it “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways”. "I love thee to the depth and breadth and height my soul can reach, when feeling out of sight for the ends of being and ideal grace. I love thee to the level of every day’s most quiet need, by sun and candle-light. I love thee freely, as men strive for right. I love thee purely, as they turn from praise. I love thee with the passion put to use in my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith. I love thee with a love I seemed to lose with my lost saints. I love thee with the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose, I shall but love thee better after death."

"Love" is a thing, but I don't think of it as one thing, I think of it as labelling the vast set of things that it encompasses. Language is not that inhibiting. -

The ineffableBy referring to "the nature of morality" you identify it as a thing, and so are trapped into thinking of it as if is one. Why should we do that? — Ciceronianus

It is the nature of words to objectify what they are referring to, to identify as a thing, whether it be "mountain", "pain", "searching" or "wanting".

If a philosopher wanted to understand a topic, such as morality, without objectifying it, then they would have to use something other than words. Philosophers use language because there is no other way. The alternative is not even to try, and that would be a dead end. -

The ineffableWord use doesn’t literally mean “changing the state of the world — Joshs

Words and action

I will have to change what I previously wrote, from " A particular word may have a set of meanings. The set of meanings doesn't change with context" to "A particular word may have a set of meanings to me. The intended meaning depends on the particular context. The set of meanings may be modified after a new experience."

I can enter a new situation not knowing the meaning of a word, for example "jiwe". Within the situation I learn the meaning of the word. The key is, as Wittgenstein wrote in the Tractatus 4.1212 "what can be shown, cannot be said" and as @Banno said "but something is done, when we talk; some agreement or coordination is reached, and novel uses of language derive from mundane uses." I learn the meaning of "jiwe" by the merchant saying "jiwe" and pointing to a stone. To learn a word needs some kind of action.

Once I have learnt the meaning of a word, once I have a concept behind the word, the next time I enter a similar situation I will be more prepared. As you say, "It is reference (memory, expectation, anticipation) modified by context, which is another name for ‘use’ or ‘forms of life’ or ‘language games’ in Wittgenstein’s sense". Almost certainly the concept I had when I entered the situation will be modified by the new experience. I may have a concept of an "apple", but after watching a program on growing apples in the Western Cape, I will definitely modify my concept. My concept of "apple", of any word, is continually changing with new experiences. What is not possible, when entering a new situation, is to be able to dismiss presuppositions and assumptions. To have, as @Constance discusses, an "innocent eye". As Gombrich said "reading an image, like the reception of any other message, is dependent on prior knowledge of possibilities; we can only recognize what we know.’ As Goodman said, ‘The innocent eye is blind and the virgin mind empty.’ The viewer is cognitively active and can never be passive. As you rightly say " Pure reference is impossible. It is reference (memory, expectation, anticipation) modified by context, which is another name for ‘use’ or ‘forms of life’ or ‘language games’ in Wittgenstein’s sense."

Once I have learnt the meaning of words, the only purpose of my words is to change the state of the world in some way. If words didn't have an affect on the world, then language would serve no purpose, and there would be no language. I say, "one coffee please", or pass me the apple, or "where is the apple" because I want a change in the state of the world. I say "hello", or "Kant is the most important philosopher", or "I am tired" because I want to change the state of mind of the person I am talking to leading to a change in the state of the world. The only purpose of words is to lead to an action

I experience a novel situation, and new experiences inevitably modify my understanding of the meanings of words. In entering a coffee house and saying, "one coffee please" and being asked "mocha frappuccino or vanilla latte?", my concept of what coffee is changes at that moment in time. The purpose of my asking "one coffee please" hasn't changed, my goal is still to be given a coffee. My goal hasn't been changed, even though the context of my interaction with the barista has changed. The next time I enter the coffee house, having my concept of coffee modified by my past experience, I may well ask for a mocha frappuccino. Again, with a new interaction with the barista, I may well gain new knowledge and again modify my concept of coffee.

Words only have meaning if they can be used to change the state of the world, ie, meaning as use. -

The ineffableI would say no, if you mean arriving at all-inclusive definitions of that they are; treating them as objects which can be definitively described, objects of knowledge if you will. — Ciceronianus

It would obviously be impossible to arrive at an all-inclusive definition of morality (for example). All we can do is strive to use words to better understand the nature of morality, surely not a futile philosophical undertaking. -

The ineffableBut there are things that we cannot express in words well, or accurately, or adequately and using words to express them (which we do all the time; which philosophers do all the time) is futile and worse "bewitching" as Wittgenstein might say — Ciceronianus

But isn't it just those things that we cannot express well in words, such as justice, ethics, morality, honour, wisdom, etc, that are exactly those things which we should strive to express well in words? -

The ineffableIt's quite easy to talk about the fact that bees and butterflies can see ultraviolet, ie, clearly not ineffable, yet can anyone actually describe what ultraviolet looks like.

-

The ineffableIdentical form does not always have identical content. — javra

I should have explained myself better, in that a particular word may have a set of meanings. For example "blue" = {the colour blue, the emotive state blue}. I am thinking of the content of the word "blue" as the set of meanings, not that meaning used in a particular context.

all words have intersubjective meanings — javra

Yes, the word "grass" means something very different to a South African than an Icelander because of their very different life experiences, yet they can both have a sensible conversation about "grass" because of its inter-subjective meaning. They can talk about the "top level" meaning rather than any "fine-tuned" meaning. -

The ineffableWords don’t have meanings as context-independent categories — Joshs

I should have been clearer about distinguishing between the different meanings of a particular word and a particular meaning of a particular word.

A particular word may have a set of meanings. The set of meanings doesn't change with context, although the intended meaning of the word is dependent on context. For example, "blue" = {the colour blue, the emotive state blue }

The set of meanings of a particular word is the foundation of a language. The set remains the same, even if the context changes. If I didn't know the set of meanings of words prior to encountering a new situation, I wouldn't know which word should be used. The set is independent of context, and pre-exists a particular context.

For Wittgenstein words don’t refer to objects, they enact forms of life. — Joshs

If I walked into a Tanzanian builder's yard and said "jiwe moja tafadhali", I know that uttering this particular sound will achieve my goal of being given a stone. The sound only has meaning in enacting a form of life. It has no meaning if not able to change the state of the world in some way. Yet the sound does refer to an object, because if it didn't refer to an object, a "jiwe", the merchant wouldn't know what I wanted. Words both enact a form of life and refer to objects. -

The ineffableAmazing how you can share the experience of a complicated gymnastic routine just by watching. — jgill

Why do people attend gymnastic competitions in their millions to watch gymnastic routines if not to share the experience of the gymnast. The visitor may not have the same skill as the gymnast in performing a gymnastic routine, but they can share in the experience.

Why would anyone go to a gymnastic competition, read a novel, attend a pop concert, the theatre, see a movie, visit an art gallery, etc, if the experience left them cold, if they felt nothing, if they couldn't share in the experience of the artist? -

The ineffableAnd I’m with the later Wittgenstein , who argues that there is no such thing as a word outside of some particular use; for a word to be is for a word to be used, and word use is always situational, contextual and personal — Joshs

I agree as well with the later Wittgenstein, in that language is a set of language games, where the purpose of language is to do something, change the world in some way. Meaning as use. It could be standing in front of a cave and saying the magical phrase "open sesame" or it could be walking into a Tanzanian builder's yard and saying "jiwe", where saying "jiwe" will achieve my goal of being given a stone. Saying "jiwe" in a Tanzanian builder's yard is one possible language game.

It is not the case that "jiwe" achieves my goal, it is the performative act of saying "jiwe" that will achieve my goal.

As you say, the context in which a word is used is crucial, but context is independent of whatever meaning a word may have. If I walked into a Parisian cafe and said "jiwe" I may get strange looks. If I said "jiwe" in a language class I might get top marks.

Wittgenstein talked about meaning as use, but this cannot mean that the meaning of a word changes dependant upon how it is being used in a particular context, but rather, the purpose a word is being used for changes with the context.

If the meaning of a word changed with context, language would have no foundation, and there would be the problem of circularity. I wouldn't know what a word meant if I didn't know the context, and I wouldn't know the context unless I knew the meaning of the word.

A stone may be used as a hammer. A stone may be used as a door stop. The meaning of "stone" is independent of any use it is put to. A stone being used as a hammer means that the nail will be driven into the wood. A stone being used as a door stop means that the door will remain open.

The way that the word is being used has a meaning and changes with context. The meaning of the word doesn't change with context. -

The ineffableQuote: "It's not easy to talk about something that can't be expressed in words."

Bertrand Russell in the Introduction to the Tractatus wrote "Mr. Wittgenstein manages to say a good deal about what cannot be said, thus suggesting to the sceptical reader that possibly there may be some loophole through a hierarchy of languages, or by some other exit. The whole subject of ethics, for example, is placed by Mr. Wittgenstein in the mystical, inexpressible region. Nevertheless he is capable of conveying his ethical opinions."

When going to the library and seeing the number of books on religion, ethics, morality, art, etc, one can only conclude that it is in fact very easy to talk about things that cannot be expressed in words.

I cannot express my private subjective experience of the colour red in words, for example, yet have no difficulty in talking about it.

As Bertrand Russell asked, where is the loophole.

In language are three rule-governed domains, form, content and use. Form includes the rules that govern how sounds are combined, rules that govern how words are constructed and rules the govern how words are combined into sentences. Content is the meaning of words and sentences. Use is the pragmatic skill of combining form and content to create functional and socially appropriate communication.

It must be the case that identical form has identical content, such that the proposition A "the bird is blue" has the same content as proposition B "the bird is blue". Therefore, if I know the content of proposition A then I also know the content of proposition B.

Therefore, generalising, if I know forms A and B, if form A is identical to form B, if I know the content of form A then I also know the content of form B.

I am human form A and I know its contents, my private subjective experiences. I observe human form B. As human form B shares more than 99% of its DNA with me, has descended from the same woman who lived in Africa between 150,000 and 200,000 years ago, and has, to all intents and purposes, the same human form as me, I can infer with almost absolute certainty that I know their contents, their private subjective experiences.

Human form B does not need to express their private subjective experiences in words for me to have an almost absolute belief that their private subjective experiences are the same as mine.

Perhaps this is the loophole that Bertrand Russell was looking for.

We can talk about that which cannot be expressed in words, because having the same form, we have the same content. -

The ineffableActions constitute much of what is ineffable. — jgill

It depends on how ineffable is defined

The Britannica Dictionary defines ineffable as "too great, powerful, beautiful, etc., to be described or expressed". The Merriam Webster Dictionary as "incapable of being expressed in words, indescribable". The Free Dictionary as " Incapable of being expressed; indescribable or unutterable".

Whilst the private subjective experience of pain cannot be described in words, it can be expressed in action, such as quickly pulling my hand away from a hot radiator. -

The ineffableEvery use of the word stone provides us with a different sense of meaning of ‘stone’. — Joshs

A stone has an uncountable number of potential uses. It can be used to hammer in a nail, be used in a game to skip over water when thrown, be used as a paperweight, keep open a door, to build the walls of a house, to construct a foundation, as ballast in a ship, etc.

If every different use of a stone gave us a different meaning of stone, then there would be an uncountable number of definitions of "stone"

I'm with @Banno who wrote "Nowadays a property is considered essential if and only if it belongs to the individual in question in every possible world." -

The ineffablesometimes, we do know the private, subjective experience of others — Moliere

If I touch a radiator, sometimes I notice that I quickly pull my hand away, grimace, put my hand into cold water and experience a pain. If I see someone else touch the same radiator, quickly pull their hand away, grimace and put their hand into cold water, I can infer with great certainty that they have felt the same pain.

Although we cannot put our private subjective experiences into words, we can put them into actions. Accepting Thomist philosophical axiom 7.7 "The same causes in the same circumstances produce always the same effects", it follows that our identical actions had an identical cause. As the proverb says, “action speaks louder than words”.

Ineffable is defined as "too great or extreme to be expressed or described in words". It may be that a private subjective experience cannot be described in words, however, as it is said that "words are actions", it could also be said that "actions are words", in which case putting our private subjective experiences into actions is a form of language, and therefore not ineffable. -

The ineffableContinuations obviously aren't the whole story, nor even necessarily part of the story for there are problems, but they seem useful in conveying the open-ended, counterfactual and inferential semantics of terms as well as accommodating the differing perspectival semantics of individual speakers. — sime

I think we are saying the same thing.

Continuation

I know very little about the concept of "continuation" in computing, other than it gives a programming language the ability to save the execution state at any point and return to that point at a later point in the program, possibly multiple times.

I understand "continuation" as the ability to return to the same instruction or idea multiple times. Using an analogy, when hiking through a hot desert, I must continually refer to a note that says "drink water".

However, I don't understand its relevance to the situation of Bob experiencing the colour white when looking at his white socks.

Observer dependent and independent properties

Going back to the question as to whether the strong flavour of coffee is an observer dependent property or an observer independent property, I would suggest that the fact that coffee has a strong flavour is an observer independent property.

The light emitted by the socks has been labelled in the English-speaking world as "white". It could well have been that a different word had been chosen, for example "green", but in the event "white" was chosen.

However, when I see "white" light, I may in fact have the private subjective experience of the colour red, and you may have the private subjective experience of the colour green. We will never know, as it is impossible for me to put my private subjective experience into words, as it is impossible for anyone to put their private subjective experience into words.

Public communication

But our private subjective experiences are irrelevant as regards communication using language. Even if I experience the colour red, I can talk about the "white" socks. Even if you experience the colour green, you can also talk about the "white" socks.

We could have a sensible conversation about the "white" socks, even though our private experiences were different.

In this sense, the public label "white" is observer independent. As regards language, "the socks are white" is true regardless of anyone's private subjective experience.

The fact that private subjective experiences of public objects are ineffable doesn't prevent sensible conversations about these public objects. -

The ineffableWhat something ‘is’ defines a use — Joshs

I don't see that there is a necessary link between what something "is" and any use that something may have, in that something may exist and yet have no use.

A stone is defined as a "hard solid non-metallic mineral matter". Stone may be used as a building material, but even if it isn't, it still remains a stone.

Coffee may be drunk, but even if never drunk, it would still be coffee.

A person is something, and if it is true that "what something "is" defines a use", then people would have no value outside of what use they had. -

The ineffableSo in your opinion, 'dark brown' and 'strong' are observer independent properties of coffee that everyone can point at? — sime

Definitions don't need to be observer independent. For example, the Cambridge Dictionary defines beauty as "the quality of being pleasing, especially to look at, or someone or something that gives great pleasure, especially when you look at it"

I agree that one only knows that coffee has a strong flavour after drinking it, in that the drinker reacts to the taste of the coffee. But even so, is it still not the case that the coffee has a strong flavour, not that the coffee causes a strong flavour? The drinker of the coffee discovers a property of the coffee. -

The ineffableSo if a person's reaction to a coffee-stimulus is of type (stimulus -> r), then the effect of coffee on that person is by definition implicitly included in the public definition of "coffee", in spite of the fact the public definition of coffee does not know about or explicitly include that person reaction — sime

Meaning is use

If people had no use for coffee, then there wouldn't be a word for coffee, and the word "coffee" wouldn't be used in language. However, as people do have a use for coffee, there is a word for coffee, and the word "coffee" is used in language.

Definitions

The fact that people have a use for coffee means that the presence of coffee causes things to happen. However, coffee is not defined by what it may cause to happen, coffee is defined by what it is, a dark brown powder with a strong flavour.

Causation

"Coffee" would still be coffee even if it didn't cause anything to happen. But if that were the case, "coffee" would not be a word in language. It is not the coffee that is causing the person to act, it is the person's desire to drink coffee that is causing the person to act, such as getting out a cafetière.

Meaning

"Coffee" means coffee, a dark brown powder with a strong flavour. "Coffee" doesn't mean that a person will act, the desire to drink coffee means that a person will act. -

The ineffableOne puzzle is how can we talk about something that cannot be put into words. Another puzzle is how can we talk about something that can be put into words.

Words exist as physical objects in the world, otherwise we wouldn't be able to talk about them, ie "word objects".

We can talk about concrete things such as apples, tables, mountains, books, and we can talk about abstract things, such as beauty, wisdom, truth, sadness. Abstract things exist in the mind, not the world. But even concrete things exist more in the mind than the world. For example, my concept of an apple has evolved over a lifetime of particular experiences, and with new knowledge is constantly changing. The concept of a city-dweller will be different to that of a farmer. The concept of a South African will be different to that of an Icelander. Our concept of the same object may be similar, but it can never be the same.

Therefore, everything we talk about, all our concepts, whether abstract or concrete, are more private than public. My concept of an aesthetic may be different to yours, but then again your concept of apple is more than likely to be different to mine.

Because word objects such as "love" and "apple" exist in the world and are simple and unchanging, I can be certain that other observers of the same word object will experience the same private concept. This is not the case with objects such as love and apple, which are complex and changing, meaning that I can be certain that other observers of the same object will not experience the same private concept.

Language is powerful because the words it uses are public. The fact that members of a society share the same private concept of public word objects, even if they don't share the private concept of the meaning of these public words, allows communication within a social group.

A word object in the world is only given meaning when linked to another object in the world. The word object "maison" has no meaning until linked to the object house. Within society such linkages are undertaken by either common usage over a long period of time or performative christenings by those accepted as authorities by the society.

Once a linkage has been made in the world between a word object such as "maison" and an object such as house, even though different individuals may probably have different private concepts of the object house, they will probably have the same private concept of the public word object "maison". Communication is then not about different private concepts of public objects but is about the same private concepts of public word objects.

For example, five apples may be labelled "red". I may in fact have the private experience of a green colour when looking at them. You may have the private experience of a blue colour. If I am asked to pass over the "red" apples, I will pass over the same apples as you, even though we have different private experiences of the colour "red". Successful communication is possible even if our private concepts of an object are different as long as the object in the world has been given a public label, ie, society has formally linked an object in the world to a word object in the world. -

The ineffableI can put the form of something into words even though I may not be able to put its content into words

Private feelings cannot be expressed in words: pain, anger, the colour red, the sound of a screech, an aesthetic experience, etc.

It is true that I cannot observe someone and experience their private pain, their anger, their experience of the colour red, etc, but I can observe their public interaction with the world.

Every different private feeling results in a different public interaction with the world: fear causes flight, anger causes attack, pain causes flinching, awe causes stillness, etc. Although I cannot observe someone's private feelings, I can observe their public interaction with the world, and I can infer that different public interactions with the world have been caused by different private feelings.

I can observe a particular effect and can infer a particular cause. I can observe someone flinching, infer that something particular caused the flinching, and name the cause "pain". The word "pain" is a label attached to the inferred cause of a particular effect, not a description of "pain". I can talk about "pain" as the inferred cause of a particular effect, although I cannot talk about what caused the effect.

The content of "pain" cannot be put into words, as the private feelings of another person, but the form of "pain" can be put into words, as the inferred cause of an observable effect in the world. I can put into words the public form of something even though I cannot put its private content into words.

Expressible form and ineffable contents are not mutually exclusive. -

Grammar Introduces LogicWell now, suppose our three-dimensional, holographic reality is a boundary to a higher four-dimensional reality with an inherent logic that transcends spacetime! What does that do to Boolean Logic? Aha! The perplexing strangeness of quantum mechanics. — ucarr

Similarly, if we lived in a spatially 2D universe, we would observe things appear and disappear for no logical reason. Yet, because we live in a spatially 3D universe, such appearances and disappearances are logically explainable.

Would it follow that, although we believe we live in a spatially 3D universe (ignoring the ten dimensions of Superstring Theory), the fact that some things appear illogical is evidence that in fact we are living in a spatially 4D universe.

The following example, attributed to the 14th C French philosopher Jean Buridan, illustrates the limits of logic. Consider the proposition "Someone at this moment is thinking about a proposition and is unsure whether it is true or false". Is it true or false?

You can’t be sure it’s false, because someone in Australia might be thinking, for example, about the Riemann Hypothesis, establishing the truth of which is an unsolved mathematical problem. But if you are unsure, then the proposition in that case is true, so you have established it and you aren’t unsure. Therefore, the proposition must be true: and yet as far as any of us know you might be the only person in the world who is thinking about a proposition at this moment, and you are not unsure of the truth of that proposition, because you have just established that it is true.

As Tarski showed, language is semantically closed, so even logic is limited by a self-referentiality. -

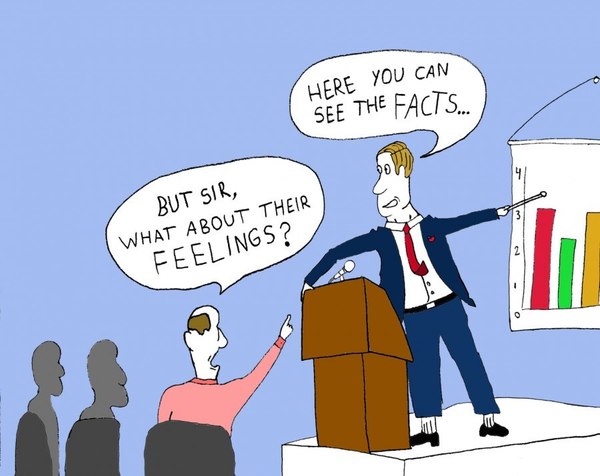

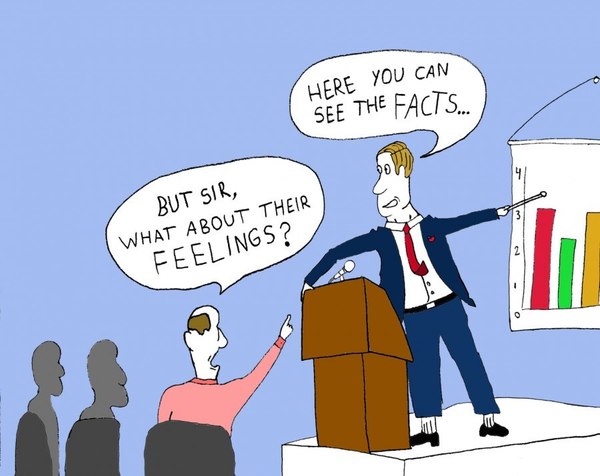

Grammar Introduces Logic@ucarr @Athena

The battle between facts and feelings.

The relationship between facts and feelings

There are various combinations:

1) I feel something but have no facts to support it. I feel that the other political party is a threat to democracy but have no facts to back up my feelings.

2) I have the facts but have no feelings about them one way or another. I know that the elephant can eat as much as 200kg of plants in a single day, but such factual knowledge is of no importance to me.

3) I feel something and have the facts to back them up. I feel that Modernist art is more artistically important than Postmodernist art, and can present facts that justify my belief.

4) Sometimes facts and feelings are coexistent. My feeling of a pain is a fact, my emotion about an aesthetic is a fact and my conscious awareness of the colour red is a fact.

A logical language may express the illogical ideas.

Language is founded on grammar and grammar is intrinsically logical. A language that was not logical would be incomprehensible. However, language using a grammar that is intrinsically logical may be used to express ideas that are intrinsically illogical: "When the day becomes the night and the sky becomes the sea, When the clock strikes heavy and there's no time for tea. And in our darkest hour, before my final rhyme, she will come back home to Wonderland and turn back the hands of time." A word such as "Wonderland" may have a logical sense even though it may not refer to any logical fact in the world.

Education requires both facts and feelings

Education without both facts and feelings is doomed to failure. We may admire Monet's The Magpie 1868 for its aesthetic and representational brilliance, but the painting becomes more memorable when we know that in the same year he wrote “I must have undoubtedly been born under an unlucky star. I’ve just been turned out without even a shirt on my back from the inn in which I was staying. My family refused to help me any more. I don’t know where I’ll sleep. I was so upset yesterday that I was stupid enough to hurl myself into the water. Fortunately no harm was done.” Effective communication rests on an appropriate mix of facts and feelings. Ineffective communication happens when one or the other is ignored.

Deconstruction of text

It is unfortunately common today for mainstream media to put their audience into a certain emotional frame of mind using only those facts that support their point of view. Taking a specific example, if at a particular moment in time five facts supporting Brexit have been discovered and five against, it would not be unexpected for the BBC to publish one for and four against, and protest that they only publish the facts, which is true. Such is an example of Derrida's concept of presence and absence, where a text must be deconstructed in order to arrive at a correct interpretation.

Deconstruction of metaphysics

Similarly in the philosophical aspect of metaphysical dualistic oppositions, where an hierarchy is established that privileges one thing over another. Certain logic is built on the metaphysical claim that internal/external, absence/presence, is sharply and clearly defined, such as the Law of Non-Contradiction. Here, both A and not A cannot be true. But this assumes A and not A are external to each other. But in reality, this is never possible. If A is a proposition, can A ever be free of the proposition not A. "I am in Paris" means that "I am not in Marseilles", "I am not dead", "Me not someone else", etc, but it must be the case that the meaning of "I am in Paris" includes the meanings "I am not in Marseilles",etc. The truth and meaning of of proposition A "I am in Paris" must include all those propositions not A.

Summary

Effective communication requires both feeling and facts and using a language that is fundamentally logical yet can express ideas that are far from logical. -

Grammar Introduces Logic@ucarr @Athena

Logic and grammar

There was no magical moment when non-human animals became human animals.

I cannot imagine a magical moment when one day animals communicated without language, had instinct without logic, were without conscious cognition of concepts, lacked any sense of morality and the next day were able to communicate with language, had reason with logic, had conscious cognition of concepts and thought about the moral implications of their actions. It seems more sensible to assume a gradual evolutionary change between animals with lower intellectual abilities to animals with a higher intellectual abilities, a process lasting millions of years.

Humans must have an innate ability to perceive what is logical

In order to perceive the colour red, I must have the a priori ability to perceive red. Humans cannot perceive the infra-red as they have no innate a priori ability to perceive infrared. Similarly, for a human to understand logic they must have a pre-existing innate ability, an ability already existing in non-human animals. It would be logically impossible for an animal to be able to perceive something of which they no innate a priori ability to perceive.

The definition of language

The Britannica defines language as "a system of conventional spoken, manual (signed), or written symbols by means of which human beings, as members of a social group and participants in its culture, express themselves" If language is defined as something used by humans, then I agree that animals don't have language. But as a cursory search on the internet brings up numerous example discussions of non-human animal language, then I cannot accept any definition of language that does not include both human and non-human animals. Of course, human language is far more complex than non-human language, but this is a difference in quantity not quality.

Grammar is logical

Traditional logic is based on grammar, such as all men are mortal, Socrates is a man, therefore, Socrates is mortal. The validity of an argument depends on the relationship between subject and predicate, meaning that if you don't know what a subject and predicate are, then you cannot determine the validity of the argument. Traditional logic depends on knowing the parts of speech. Parts of speech such as categoramatic words, nouns such as men, mortal and Socrates and syncategorematic words, such as verbs, adjectives and adverbs. Parts of speech such as quantity, such as how much, how many and quality, such as intelligent, honest. Parts of speech such as prepositions such as against, on top of and conjunctions, such as and, but, although. To learn grammar requires one to learn logic, to have the logical skill of analysis and synthesis, how to make distinctions and how to see resemblances.

The natural world is logical

Life has evolved in synergy with the natural world over 750 million years, not independently, but as a single unity. Life has been dependent on its survival because of its intimate relationship with the world in which it lives. Logic is intrinsic in the world and logic begins in the space-time of the world. For example, an object A is object A, object A is not object B, if object A is to the left of object B then object B is to the right of object A, if object B is added to object A then there are two objects, if there are three objects and one is removed then two objects remain. The logic humans use is founded on the logic they discover in the world. Onto this fundamental logic discovered in the natural world that is known instinctively, innately and a priori, a more complex logic may be developed within language, such as the study of arguments, inductive and deductive logic, syllogisms, propositional logic, first order logic etc.

How to discover the nature of reality using a semantically closed language

The question is how can language serve as a basis of a metaphysical philosophy that enquires about the nature of reality, of what is universal and necessary. As Tarski observed, language is semantically closed, yet the nature of reality is external to the language that is attempting to discover it. As Wittgenstein said in the Tractatus, "what can be shown, cannot be said". As David Hume showed our knowledge is not absolute but based on inference, where all we can say is that after observing the constant conjunction between two events A and B for a duration of time, we become convinced that A causes B.

Understanding using language can only be metaphorical

It seems that the best we can achieve in our understanding of the nature of reality is our use of language as metaphorical, in that all we can really say, as it were, is that There Are More Stars In The Universe Than There Are Grains Of Sand On Earth. -

Another logic question!The argument (taken from Fred Bieser — KantDane21

It would be easier if you gave a link to the source, as premise one doesn't make any sense

and premise two is ungrammatical. -

form and name of this argument?Another route would be to note that Kant is apparently making a point about cognition — Srap Tasmaner

The OP proposes: "Either all cognition is cognition of appearance, in which case there can be no cognition of noumena, or there can be cognition of the noumenon, in which case cognition is not essentially cognition of appearance"

I am unsure whether the intention is to put the above passage into first order logic as it stands independently of Kant or into first order logic such that it agrees with Kant's philosophy.

Because it seems that the above passage does not agree with Kant's philosophy, in that he wrote in Critique of Pure Reason: "we can have cognition of no object as a thing in itself, but only insofar as it is an object of sensible intuition, i.e. as an appearance."

Of course, as an exercise it can still be put into first order logic regardless of Kant's philosophy.

As an aside, even though Kant argued that there can be no cognition of noumena, there can still be cognition about noumena, as this thread attests. -

Grammar Introduces LogicOur disagreement seems to be about what logic has to do with thinking foolishly or logically. — Athena

-

Grammar Introduces LogicBird sounds and language are not the same thing. — Athena

There is language and Language

Lakna Panawala's article What is the Difference Between Humans and Animals Brain makes sense to me.

She wrote:

1) The main difference between humans’ brain and animals’ brain is that humans’ brain has a remarkable cognitive capacity, which is a crowning achievement of evolution whereas animals’ brain shows comparatively less cognitive capacity.

2) Humans are more intelligent due to their increased neural connections in the brain while animals are comparatively less intelligent due to fewer neural connections.

3) Humans’ brain has the ability of complex processing such as conscious thought, language, and self-awareness due to the presence of a large neocortex while animals’ brain has a less ability of complex processing.

I find it hard to believe that there was a magical moment when one day there was no language and the next day there was language. Surely, language has developed over a long period of time.

Lakna wrote that humans have more ability of complex processing than non-human animals, not that non-human animals don't have any ability of complex processing. She wrote that complex processing includes conscious thought, language and self-awareness.

@ucarr used the division language-general of non-human animals and language-verbal of humans. Another terminological division could be between language of non-human animals and Language of humans, where language with a capital L is defined as language practised by humans. If this were the case, then I would agree that non-human animals don't have Language, although I would still argue that non-human animals do have language.

Every living thing communicates in some way. To be able to communicate requires a means of communication. Language is a means of communication.

Non-human animals communicate using non-verbal signals, bees dance, hummingbirds use visual displays, etc. Humans communicate using both non-verbal and verbal communication, smiling, crying, speaking, writing, etc.

The Britannica defines human language as a system of conventional spoken, manual (signed), or written symbols by means of which human beings, as members of a social group and participants in its culture, express themselves.

Wikipedia defines animal language as communication using a variety of signs, such as sounds and movement.

In summary, both non-human animals and humans communicate using language. Non-human animal language is non-verbal, human language is both non-verbal and verbal. -

Grammar Introduces LogicOut of interest who says crows don't have language? — Benj96

My response to @ucarr presented a hypothetical, not my belief that crows don't have language.

@ucarr had previously written: "Language and logic are synonyms. This boils down to saying you can’t practice cognition outside of language".

If it is true as I believe that the crow is using cognition, and if it is true as @ucarr wrote that it is not possible to cognize outside language, then it would follow that crows must have language. -

form and name of this argument?(1) is valid — Srap Tasmaner

I cognize something x. Cognition is a higher level function of the brain. I can cognize about x both as an appearance and a noumenon.

As regards cognition, then why not A → (~B ˄ B) ?

This also follows the two-aspect interpretation of Kant's Transcendental Idealism. -

form and name of this argument?"Either all cognition is cognition of appearance, in which case there can be no cognition of noumena, or there can be cognition of the noumenon, in which case cognition is not essentially cognition of appearance" — KantDane21

As regards cognition, it is not a case of either-or, in that I can both cognize about appearance and cognize about noumena, such that P ˄ Q is possible.

Cognizing about an appearance and cognizing about something that caused the appearance are not mutually exclusive.

Although I can cognize about the concept of noumena, because, by the definition of noumena, I can never perceive noumena in the world, I can never cognize about particular noumena. -

form and name of this argument?cognition — KantDane21

Perhaps "perception" would be a more suitable word than "cognition" in this situation. Cognition implies an active act of manipulating concepts. Perception implies a passive observation.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum