-

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

Yes, quite so. Two my eyes, this debate looks like a microcosm for idealism vs realism. But with a difference, that in some sense it is for real. But then I ask myself How is that possible unless reality and our ideas are really in conflict? We have come up with some new ideas - wavicles, entanglement, etc - and no doubt more will be required.

It's quite simple really. From one point of view, the teams on the field are separate entities; from another, they are a unity - together, they are a fight, or a match. (From a third point of view, each team is made up of 11 individuals.) Each pair of shoes is a unity of two individual shoes. I don't see a problem here.I may be making myself misunderstood. The error I mean is to treat the "observer" as in a separate world from the "observed." They're not one and the same, though. — Ciceronianus -

J

2.4kI don't see a problem here. — Ludwig V

J

2.4kI don't see a problem here. — Ludwig V

The problem, I think, comes when we ask which of these points of view (if any) reflect how the world really is. Is there any way to make the case that some points of view are ontologically privileged? -- that is, that they describe the world more accurately than their competitors? -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

Take a weather map, a geological map and a road map of the same territory. They are not competitors, and they describe different aspects of the world. The question of which is the most accurate doesn't apply. They are all about truth, but not about the same truth. The question which is the best map depends on the context - what you are doing, what your interests are.The problem, I think, comes when we ask which of these points of view (if any) reflect how the world really is. Is there any way to make the case that some points of view are ontologically privileged? -- that is, that they describe the world more accurately than their competitors? — J

Some puzzle pictures can be taken in more than one way. Again, those questions don't arise - the interpretations are not in competition with each other.

The territory and the picture are such that they can be represented in more than one way. That's the reality. There's no way to make a choice.

On the other hand, I'm not at all sure that the "interpretations" model applies to this debate. Some form of realism seems to me much more satisfying than anti-realism or idealism. The latter seems to be make far too much of our limitations and failing to recognize that our senses and our language are very powerful tools. -

Janus

18kThe irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental.

Janus

18kThe irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

That's a new one to me.The irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, then seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental. — Janus -

J

2.4kThey are all about truth, but not about the same truth. — Ludwig V

J

2.4kThey are all about truth, but not about the same truth. — Ludwig V

Yes. This invites a couple of responses:

First, are some truths more "natural" or "about the world" than others? It is true, for instance, that several stars, when grouped together, make a constellation. But that is so because of something we humans do. It is not actually a feature of the natural world (using a common sense of what is natural).

Second, how far can this be pushed? See Ted Sider's ideas about "objective structure." His "grue" and "bleen" people divide up the visual world in a bizarre way, yet everything they say about it is true. Sider argues, and I agree, that nonetheless they are missing something important about how the world really is.

The irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims — Janus

Interesting point. In general, I think scientific realism had better include some truths about the role of consciousness -- it would be drastically incomplete otherwise. But what are these truths? Stay tuned . . . -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kThe irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental. — Janus

I’ve been studying Michel Bitbol on philosophy of science, and he sees many of these disputes as arising from a shared presupposition: treating mind and matter as if they were two substances, one of which must be ontologically fundamental. In that sense, dualists and physicalists often share two assumptions—first, that consciousness is either a thing or a property of a thing; and second, that physical systems exist in their own right, independently of how they appear to us.

On Bitbol’s reading, quantum theory supports neither position. It doesn’t establish the ontological primacy of consciousness conceived as a substance—but it also undermines the idea of self-subsisting physical “things” with inherent identity and persistence. What it destabilises is the very framework in which “mind” and “matter” appear as separable ontological kinds in the first place.

Because both dualism and materialism tacitly treat consciousness as something—a thing among other things—while also presuming that physical systems exist independently of observation, the observer problem then appears as a paradox. The realist question becomes: what are these objects really in themselves, prior to or apart from any observation?

This line of thought aligns closely with what has humorously been called Bitbol’s “Kantum physics”—a deliberate play on words marking the Kantian dimension of quantum theory. Just as Kant argued that we know only phenomena structured by our cognitive faculties, Bitbol argues that quantum mechanics describes the structure of possible experience under the conditions of measurement. It is less a picture of an observer-independent world than a framework specifying how observations arise from our experimental engagement with it.

See The Roles Ascribed to Conscousness in Quantum Physics (.pdf) He's also done a set of interviews with Robert Lawrence Kuhn recently.

-

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

This is a real problem. I don't know the answer and perhaps there isn't one - or not just one. In this case, we should compare constellations with another case. I suggest the solar system as being an actual feature of the world. ("natural" just makes additional complexity). These cases could also usefully be compared with the sun. My first instinct is to say that the solar system is maintained by a collection of what we call "laws of nature". The sun falls into the class of concepts of objects (medium-sized dry goods is not particularly helpful in this case, but indicates what I have in mind).It is true, for instance, that several stars, when grouped together, make a constellation. But that is so because of something we humans do. It is not actually a feature of the natural world (using a common sense of what is natural). — J

I agree with you. My first stab at identifying what is missing is that this notion of truth is very thin. It is neither use nor ornament. It consequently doesn't have a future in our everyday language. I don't rule out the possibility of concepts like these finding a use somewhere some day. On the other hand, I'm a bit doubtful whether "how the world really is" is a useful or usable criterion for what we are trying to talk about.Second, how far can this be pushed? See Ted Sider's ideas about "objective structure." His "grue" and "bleen" people divide up the visual world in a bizarre way, yet everything they say about it is true. Sider argues, and I agree, that nonetheless they are missing something important about how the world really is. — J

I had a look at the article you linked to. It's very promising, so I've saved it. The concluding paragraph has a lot going for it.

The first task is to clarify the sense of "fundamental" in this context.The point of metaphysics is to discern the fundamental structure of the world. That requires choosing fundamental notions with which to describe the world. No one can avoid this choice. Other things being equal, it’s good to choose a set of fundamental notions that make previously unanswerable questions evaporate. There’s no denying that this is a point in favor of ontological deflationism. But no one other than a positivist can make all the hard questions evaporate. If nothing else, the choice of what notions are fundamental remains. There’s no detour around the entirety of fundamental metaphysics. — 'Ontological Realism' - Theodore Sider -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

We certainly a conception of mind vs matter that not only distinguishes them, but shows their interdependence - co-existence in the same world. The concept of categories was supposed to do this, but it seems to me to posit them as separate without explaining their unity.On Bitbol’s reading, quantum theory supports neither position. .... What it destabilises is the very framework in which “mind” and “matter” appear as separable ontological kinds in the first place. — Wayfarer

That's the beginning of a diagnosis of the problem. But it doesn't help much in trying to resolve it. Your realist question doesn't help either. Trying to describe objects "in themselves" apart from any observation is like trying to pick up a pen without touching it.Because both dualism and materialism tacitly treat consciousness as something—a thing among other things—while also presuming that physical systems exist independently of observation, the observer problem then appears as a paradox. The realist question becomes: what are these objects really in themselves, prior to or apart from any observation? — Wayfarer -

J

2.4k. . . an actual feature of the world. ("natural" just makes additional complexity). — Ludwig V

J

2.4k. . . an actual feature of the world. ("natural" just makes additional complexity). — Ludwig V

It's the familiar problem of trying to find terminology that isn't hopelessly vague and/or controversial. "Actual feature" is fine with me, though "actual" has some of the same issues as "natural." But short of coining new terms and defining them precisely, what's to be done?

My first stab at identifying what is missing is that this notion of truth is very thin. It is neither use nor ornament. It consequently doesn't have a future in our everyday language. — Ludwig V

I agree, we can mount a pragmatic case for why certain uses of "truth" are to be preferred. Sider is coming at it slightly differently; he wants to say that our usual construals of how the world is are useful because they're true, not vice versa -- but the problem is, truth isn't enough. What the grue and bleen people say is also true. Your idea about "thin truth" is on this wavelength too, I think. Sider brings in the idea of fundamental truths, truths that are about "objective structure" -- the latter phrase I find problematic, but surely he's right that there are orders of truth, some more fundamental than others to understanding. It's not enough just to say something true -- we want the true things we say to create a picture we can also understand.

I'm a bit doubtful whether "how the world really is" is a useful or usable criterion for what we are trying to talk about. — Ludwig V

Sure, same point as above. What the hell do we call it? An approximation would be "the world without perspectives or observers" but that description is starting to sound almost quaint. But are we ready to abandon the difference between "making a mistake" and "getting it right"? If these two possibilities still make sense, then whatever marks the difference is what we mean by "how the world really is" -- not much help, is it.

the choice of what notions are fundamental remains. There’s no detour around the entirety of fundamental metaphysics. — 'Ontological Realism' - Theodore Sider

This seems particularly important to me. If you say "There are no fundamental notions," you have nonetheless made an important statement about what is and isn't fundamental.

What it destabilises is the very framework in which “mind” and “matter” appear as separable ontological kinds in the first place. — Wayfarer

Yes. If we can find a way to re-stabilize this so that "mind" and "matter" still refer, but not to irreconcilable ontological kinds in the ways that now seem unavoidable, we'll have come far. -

Janus

18kThat's a new one to me. — Ludwig V

Janus

18kThat's a new one to me. — Ludwig V

That doesn't tell me anything much. Do you have anything more to add?

Interesting point. In general, I think scientific realism had better include some truths about the role of consciousness -- it would be drastically incomplete otherwise. But what are these truths? Stay tuned . — J

I'm not sure what you mean by "scientific realism", but the study of consciousness seems to be irrelevant to most of the hard sciences, and we do have cognitive science and psychology to deal with consciousness, among other things. I'm not sure it qualifies as a science, but we also have phenomenology.

I’ve been studying Michel Bitbol on philosophy of science, and he sees many of these disputes as arising from a shared presupposition: treating mind and matter as if they were two substances, one of which must be ontologically fundamental. In that sense, dualists and physicalists often share two assumptions—first, that consciousness is either a thing or a property of a thing; and second, that physical systems exist in their own right, independently of how they appear to us. — Wayfarer

I don't see it as a question of substances. I think that way of thinking is anachronistic. We don't need to talk about 'physical vs mental'. Existence or being is fundamental. First there is mere existence of whatever, then comes self-organized existence (life) and with that comes cognition. Self-organized existents are able, via evolved existent structures known as cells and later sensory organs composed of cells to be sensitive to both the existents which constitute the non-living environment and of course other living existents that share the environment with them. Science shows us that the ability to model that sensitivity has evolved to ever-increasing levels of complexity and sophistication, with a major leap coming with the advent of symbolic language.

Is consciousness a thing? Not if you mean by 'thing' 'an object of the senses'. Digetsion is not an object of the senses either yet consciousness, like digestion, can be thought of as a process, and processes may be referred to as things.

On Bitbol’s reading, quantum theory supports neither position. It doesn’t establish the ontological primacy of consciousness conceived as a substance—but it also undermines the idea of self-subsisting physical “things” with inherent identity and persistence. What it destabilises is the very framework in which “mind” and “matter” appear as separable ontological kinds in the first place. — Wayfarer

I agree that quantum theory supports neither position (re fundamental substances). I don't agree that it undermines the idea of self-existing things, meaning things that exist in the absence of percipients. I also don't think it has anything say about mind and matter being different ontological kinds, as that is merely a matter of categorization. They are different kinds of things, since matter is thought of as constitutive and mind is thought of as perceptive. Matter is thought of in terms of particles or building blocks, whereas mind is thought of as a process. I don't see that QM dispenses with the idea of building blocks at all, although obviously the old 'billiard ball' model is no longer viable. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't agree that it undermines the idea of self-existing things, meaning things that exist in the absence of percipients. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't agree that it undermines the idea of self-existing things, meaning things that exist in the absence of percipients. — Janus

That precise point is written all over the history of quantum mechanics. The customary dodge is 'well, there are different interpretations' - but notice this also subjectivises the facts of the matter, makes it a matter of different opinions. If you don't see it, you need to do more reading on it. The fields of quantum physics are in no way 'building blocks', which is a lame attempt to apply a metaphor appropriate to atomism to a completely different conceptual matrix.

The whole debate between Bohr and Einstein, whilst very technical in many respects, is precisely about the question of whether the fundamental objects of physics are mind-independent. This has already been posted more than once in this thread, but it still retains relevance:

From John Wheeler, Law without Law:

The dependence on what is observed upon the choice of experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the view that the universe exists "out there", independent of all acts on observation. In contrast Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it givs us. Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word “phenomenon”. In today's words Bohr’s point – and the central point of quantum theory – can be put into a single, simple sentence. "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed ) phenomenon”.

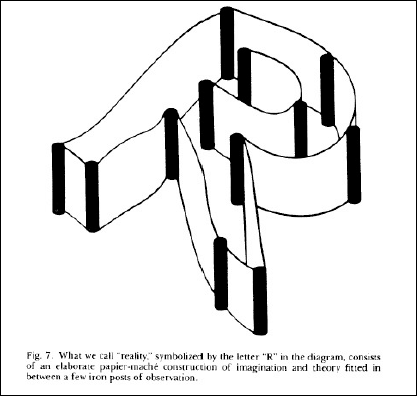

‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

A clear a statement of 'the mind created world', as I intended it, as you're likely to find anywhere. -

Janus

18kThat precise point is written all over the history of quantum mechanics. The customary dodge is 'well, there are different interpretations' - but notice this also subjectivises the facts of the matter, makes it a matter of different opinions. If you don't see it, you need to do more reading on it. The fields of quantum physics are in no way 'building blocks', which is a lame attempt to apply a metaphor appropriate to atomism to a completely different conceptual matrix. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kThat precise point is written all over the history of quantum mechanics. The customary dodge is 'well, there are different interpretations' - but notice this also subjectivises the facts of the matter, makes it a matter of different opinions. If you don't see it, you need to do more reading on it. The fields of quantum physics are in no way 'building blocks', which is a lame attempt to apply a metaphor appropriate to atomism to a completely different conceptual matrix. — Wayfarer

I don't have the time to search for specific citations to present, but I know from having watched many interviews with Quantum Physicists that the idea of particles as real entities is still a live option. So, I asked Claude, and this is the answer I received:

Hi Claude, I wonder if you can tell me what the consensus is today in Quantum Mechanics as to whether fields are composed of particles?

This is a fascinating question that remains actively debated among physicists and philosophers of science. There isn't a firm consensus, but rather several competing views:

The main perspectives:

Fields as fundamental - Many contemporary physicists and philosophers view fields as real, continuous entities, while particles are merely useful approximations in specific contexts

In this view, what we call "particles" are actually excitations or disturbances in underlying quantum fields.

Particle ontology - Some defend a moderate form of object realism with respect to particle-like entities, particularly when distinguishing between quantum field theory as a framework versus specific theories like the Standard Model.

Mixed or functionalist approach - Some recent proposals argue for a mixed ontology of particles and fields, suggesting both are legitimate descriptions that serve different functional roles in the theory.

Key challenges to a particle interpretation:

The evidence weighs against viewing fields as "composed of" particles in any simple sense. The number of particles and their energy-momentum are not invariant in curved spacetimes, particularly in the presence of black holes, while what remains invariant is the energy-momentum of the fields

MDPI. This suggests fields are more fundamental.

Current state of debate:

The question remains philosophically complex. As of 2024, there's active debate about whether this is even the right question to ask - some argue we should focus on how particles and fields function consistently within quantum field theory rather than which is "more real."

In any case even if energy fields are fundamental, and matter and energy are equivalent, and fields exist, then it follows that something exists independently of minds if QM is actually showing us something about objective reality. On that view embodied minds and bodies and entities of all kinds as well as perception and thought itself would also be "excitations in a field".

The other point is that, if you think science shows us only things as they are apparent to us, then the idea of independent existents cannot be ruled out on that view. You might say that all we know is that there appear to us to be independent existents, but what appears to us cannot answer the question as to what is independently of us and so we cannot know whether there are or are not such entities.

I am not interested in defending one view or the other, but only in establishing what can, with intellectual humility and honesty, be said.

As to the Wheeler diagram, it says nothing about whether the ways in which the world can be divided up are more or less in accordance with the actual structure of the world. -

J

2.4kI'm not sure what you mean by "scientific realism", but the study of consciousness seems to be irrelevant to most of the hard sciences — Janus

J

2.4kI'm not sure what you mean by "scientific realism", but the study of consciousness seems to be irrelevant to most of the hard sciences — Janus

By "scientific realism," I meant to denote the common-or-garden-variety conception of science. It may be flawed or dead wrong at the quantum level, but we all know it works at most other levels. And by "works," I only mean that it generates predictions that prove remarkably accurate, and at the same time provides us with a powerful measure for what it means to be right or wrong about the physical world.

So, could there be such a practice that, taken all in all, didn't include a theory of consciousness? I don't see how. You're right that, in any given hard science, we may not need that theory; we can assume the fact of consciousness. But if our goal is to give a complete account of what there is, then to leave consciousness out would be laughable. This tells me that we're still in early days of forming such an account. You say that we have cognitive science and psychology to deal with consciousness, and in a way we do, but neither field provides a grounding theory of what consciousness is, or why it occurs. Like the hard sciences, consciousness is accepted as a given (or, for some, deflated or reduced or denied).

So, one of the most extraordinary and omnipresent facts about the world -- that many of its denizens have an "inside," a subjectivity -- still awaits a unified theory. I know many on TPF doubt that science can provide this. I'm agnostic; let's wait and see. -

Janus

18kBut if our goal is to give a complete account of what there is, then to leave consciousness out would be laughable. This tells me that we're still in early days of forming such an account. You say that we have cognitive science and psychology to deal with consciousness, and in a way we do, but neither field provides a grounding theory of what consciousness is, or why it occurs. Like the hard sciences, consciousness is accepted as a given (or, for some, deflated or reduced or denied).

Janus

18kBut if our goal is to give a complete account of what there is, then to leave consciousness out would be laughable. This tells me that we're still in early days of forming such an account. You say that we have cognitive science and psychology to deal with consciousness, and in a way we do, but neither field provides a grounding theory of what consciousness is, or why it occurs. Like the hard sciences, consciousness is accepted as a given (or, for some, deflated or reduced or denied).

So, one of the most extraordinary and omnipresent facts about the world -- that many of its denizens have an "inside," a subjectivity -- still awaits a unified theory. I know many on TPF doubt that science can provide this. I'm agnostic; let's wait and see. — J

I'm a little inclined to be on the side of thinking that a unified theory is impossible, but I'm not adamant about it. It seems to me that we understand things via science by being "outside" them, by being able to analyze and model them in accordance with how they present themselves to us. I don't find it plausible that how they present to us is determined by consciousness, but I think it is more reasonable to think that it is determined by the physical constitutions of our sensory organs, nervous system and brain, as well as by the actual structures of the things themselves.

The problem with trying to model consciousness itself is that it is the thing doing the modeling, and we cannot "get outside of it", so we seem to be stuck with making inferences about what it might be from studying the brain being the best we can do, or going with what our intuitions "from inside" tell us about its nature. -

Punshhh

3.6k

Punshhh

3.6k

This is what I was talking about in the other thread, (Cosmos created mind), I am interested in developing ways to break out of this straight jacket. But I don’t have the philosophical language to ground it in digestible philosophy. It just comes across as fanciful wishful thinking.The problem with trying to model consciousness itself is that it is the thing doing the modeling, and we cannot "get outside of it", so we seem to be stuck with making inferences about what it might be from studying the brain being the best we can do, or going with what our intuitions "from inside" tell us about its nature.

I see two initial problems, firstly the problem of how a mind can talk about itself with itself and not be convinced that it’s impossible to do it impartially, or that it’s an insurmountable stumbling block.

Secondly how we break out of the state that the world presents us with to some kind of objective starting point, or foundation.

In mysticism (my brand of mysticism) the first problem is covered extensively with a series of processes and practices. But which comes across to a philosopher as dogmatic spirituality, or wishful thinking.

Secondly I have developed a series of conceptual tools by which one can break out of the straight jacket of the world being the way it presents to us. Which again comes across to philosophers as woo woo, spirituality, or wishful thinking.

Yes, but the physical constitutions themselves are parts of the structures of the things themselves. Even the mind, via the brain, as used in our day to day thinking is shaped, framed by these structures. Sooner, or later we have to start considering something that isn’t shaped in this way, in consciousness, but is nevertheless shaped by other as yet unrecognised structures. This is usually described as the soul, although I prefer to describe it as the higher mind.*I don't find it plausible that how they present to us is determined by consciousness, but I think it is more reasonable to think that it is determined by the physical constitutions of our sensory organs, nervous system and brain, as well as by the actual structures of the things themselves.

Unless we go there, no one is going to make any progress on putting together a unified theory.

* by higher mind, I mean a part of our mind that is recognised as conceptually free, or independent of the mind clothed in the world that we inhabit mostly in day to day life. Like a kind of Platonic region, concerned with pure thought, being etc. -

J

2.4kThe problem with trying to model consciousness itself is that it is the thing doing the modeling, and we cannot "get outside of it", so we seem to be stuck with making inferences about what it might be from studying the brain being the best we can do, or going with what our intuitions "from inside" tell us about its nature. — Janus

J

2.4kThe problem with trying to model consciousness itself is that it is the thing doing the modeling, and we cannot "get outside of it", so we seem to be stuck with making inferences about what it might be from studying the brain being the best we can do, or going with what our intuitions "from inside" tell us about its nature. — Janus

I always feel somewhat dimwitted when I read this objection. It's clearly cogent and important for many who think about consciousness. Yet I can't see the force of it. Why can't a conscious mind model consciousness? Why would it be necessary to "get outside of" our own mind in order to do it? Perhaps even more significantly, why is "modeling" even necessary? Why do we need "intuitions from the inside"? Why can't we just explain it, without worrying about whether we can somehow experience our explanation at the same time? We explain many things that are inaccessible to us. We don't need the experience of being a planet in motion in order to explain planetary motion. Why is consciousness different?

To summarize my questions: Why can't subjectivity be explained objectively? Why conflate explanation with experience? You can't experience your subjectivity objectively, true, but why would that be necessary in order to explain subjectivity in general?

As I say, there must be something obvious here I'm not seeing. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThis is from Adam Frank, one of the co-authors of The Blind Spot of Science (alongside Marcello Gleiser and Evan Thompson.) Frank is a professor of astrophysics at Rochester University. But he's also a longtime Zen practitioner, and in this excerpt, he talks about the strengths and weaknesses of the ideal of objectivity in philosophy and science. My bolds.

Wayfarer

26.1kThis is from Adam Frank, one of the co-authors of The Blind Spot of Science (alongside Marcello Gleiser and Evan Thompson.) Frank is a professor of astrophysics at Rochester University. But he's also a longtime Zen practitioner, and in this excerpt, he talks about the strengths and weaknesses of the ideal of objectivity in philosophy and science. My bolds.

The verb “to be” is something that science doesn’t really know how to deal with. What has happened is that scientists have often ignored it and tried to pretend that it doesn’t exist. They’ve sort of defined it away, and that’s actually fine for some problems—doing that has actually allowed science to make a whole lot of progress. For instance, if you’re just talking about balls on a pool table, fine: you can totally get the Observer out of it. But there is a whole class of problems that are at the very root of some of our deepest questions, like the nature of consciousness, the nature of time, and the nature of the universe as a whole, where doing that (taking the Observer out) limits you in terms of explanations, and it’s really bound us up in a lot of ways. And it has really important consequences, both for science, our ability to explain things, but also for the culture that emerges out of science.

In order to remove the Observer you have to treat the world as dead, you know? One of the things that for me is really important is to move away from like words like “the Observer” and focus on experience. Because part of the problem with experience is that it’s so close to us that we don’t even see it. And it’s only in contemplative practice that you really have to deal with it. …

Physicists are in love with the idea of objective reality. I like to say that we physicists have a mania for ontology. We want to know what the furniture of the world is, independent of us. And I think that idea really needs to be re-examined, because when you think about objective reality, what are you doing? You’re just imagining yourself looking at the world without actually being there, because it’s impossible to actually imagine a perspectiveless perspective. So all you’ve done is you’ve just substituted God’s perspective, as if you were floating over some planet, disembodied, looking down on it. And, so, what is that? This thing we’re calling objective reality is kind of a meaningless concept because the only way we encounter the world is through our perspective. Having perspectives, having experience: that’s really where we should begin. — Adam Frank, Astrophysicist and Zen Practitioner

-

Janus

18kI see two initial problems, firstly the problem of how a mind can talk about itself with itself and not be convinced that it’s impossible to do it impartially, or that it’s an insurmountable stumbling block. — Punshhh

Janus

18kI see two initial problems, firstly the problem of how a mind can talk about itself with itself and not be convinced that it’s impossible to do it impartially, or that it’s an insurmountable stumbling block. — Punshhh

But people can talk about their minds―we do it all the time. But we do so from the perspective of how things seem to us. And how all things in that context seem to me may not be how they seem to you―even though there will likely be commonalities due to the fact that we are both human.

Individually we inhabit the inner world of our own experience―yet that experience is always already mediated by our biology, our language, our culture, our upbringing with all its joys and traumas. Our consciousness is not by any means the entirety of our psyche. There can be no doubt that most of what goes on in us is below the threshold of awareness. If Jung is right there is a personal unconscious and a collective unconscious, that some recent theorists believe is carried in the DNA―like a collective memory.

I don't know if you have heard of Iain McGilchrist, but his neuroscientific investigations have led him to believe that the right hemisphere drives the arational intuitive synthetic mode of consciousness and the left the rational analytic mode. His ideas are presented in The Master and His Emissary. It makes intuitive sense to me, but it is (at this stage at least) obviously not a falsifiable theory of the human mind, and even if it were it still wouldn't answer the deepest questions about the relationship between the mind and the brain.

In any case if his picture is right, when we try to force the "right' mode of understanding into the 'left' mode of thinking we inevitably lose the creative "livingness" of our intuitive understanding. The rational left mode demands logical validity, and intersubjective confirmability, as is the case with science, but our individual intuitive understandings cannot be experienced by others―they have their own, and so the attempt to develop an overarching theory seems to be doomed to fail.

That doesn't mean there cannot be expressions which evoke sympathetic responses by those of like mind of course―but I think that's the best we can hope for. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt makes intuitive sense to me, but it is (at this stage at least) obviously not a falsifiable theory of the human mind, and even if it were it still wouldn't answer the deepest questions about the relationship between the mind and the brain. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kIt makes intuitive sense to me, but it is (at this stage at least) obviously not a falsifiable theory of the human mind, and even if it were it still wouldn't answer the deepest questions about the relationship between the mind and the brain. — Janus

The point of falsifiability is not that it's the gold standard for all true theories. The point is only that it allows for the distinction between genuine empirical theory and pseudo-theories. The original examples that Popper gave were Marxism and Freudianism - very influential in his day and often regarded as scientific — when, he said, they could accomodate any new facts that came along. But conversely, that doesn't mean that rationalist philosophy of mind can't be true, because it is not empirically falsifiable. That is to regard empiricism as the sole criterion of validity, which wasn't how the distinction was intended by Popper.

I've noticed and read about McGilchrist but haven't taken the plunge - too many books! But I'm totally sympathetic to what I take to be his orientation. -

Janus

18kThe point of falsifiability is not that it's the gold standard for all true theories — Wayfarer

Janus

18kThe point of falsifiability is not that it's the gold standard for all true theories — Wayfarer

Falsifiability and confirmability are the gold standards for scientific observations, hypotheses and some scientific theories, and I was discussing the possibility of a scientific theory of mind or consciousness.

So, for example, Take the thesis that all swans are white, it will be falsified by discovering one swan of another colour. On the other hand in the case of the opposite thesis that not all swans are white, it will be verified by discovering one swan of another colour.

The other consideration when it comes to theories of mind or consciousness, is that we develop them natively in terms of how mind and consciousness intuitively seem, and the ways in which that seeming is mediated by culture, language and biology itself seem too nebulous and complex, as well as different in individual cases, to be definitively unpacked.

Also there is the general incommensurability of explanations given in terms of reasons and explanations given in terms of causes.

But conversely, that doesn't mean that rationalist philosophy of mind can't be true, because it is not empirically falsifiable. — Wayfarer

It's not a matter of strictly rational, i.e. non-empirical, theories being true or false, but of their being able to be demonstrated to be true or false. Even scientific theories, as opposed to mathematical and logical propositions and empirical observations, cannot be strictly demonstrated to be true. "Successful" and thus accepted theories are held provisionally unless observations which cannot be fitted into their entailments or that contradict them crop up. -

J

2.4k

J

2.4k

Physicists are in love with the idea of objective reality. I like to say that we physicists have a mania for ontology. We want to know what the furniture of the world is, independent of us. — Adam Frank, Astrophysicist and Zen Practitioner

This is a good point. But doesn't it apply to any attempt at an objective viewpoint, not to viewing consciousness especially? If I understand the point that @Janus and yourself and others are making, there's supposed to be something different and special about the problem when it comes to consciousness. Frank seems to be saying that all objective reality is "kind of a meaningless concept" -- that we delude ourselves about attaining God's perspective. That may be. But I want to understand why there's a special problem about subjectivity, viewed as a phenomenon we all know to be as real as anything else, and therefore want to understand.

But people can talk about their minds―we do it all the time. But we do so from the perspective of how things seem to us. And how all things in that context seem to me may not be how they seem to you―even though there will likely be commonalities due to the fact that we are both human. — Janus

My response here is similar: Yes, there is a problem about perspective, and whether how things seem to me will be the same as how things seem to you. But why isn't this just as much of a problem for understanding trees as it is for understanding consciousness? We'll always struggle to find commonality of perspective. The result may be called objective, or intersubjective, or merely agreed-upon, but we recognize that it is very different from "J's opinion" about something. Don't we want something similar, in the end, as we inquire into consciousness?

It seems, again, to come down to a difference between experience and explanation. I can never experience your subjectivity, but why would that mean I can't explain how it comes about? -

Janus

18kBut why isn't this just as much of a problem for understanding trees as it is for understanding consciousness? — J

Janus

18kBut why isn't this just as much of a problem for understanding trees as it is for understanding consciousness? — J

The reason is that if we are standing in front of a tree we can point to its features and we will necessarily agree. I say it has smooth bark, and if I and you are both being honest we must agree. I say the leaves have toothed margins, and again we must agree. I say the trunk diameter at base is 400 mm, that the leaves are compound or that they they single but opposite, and again we must agree if we are being honest. If we are suitably trained we will agree as to what species the tree is, and if one of us or both or not we can refer to a guide to tree species and identify the tree. We can agree even about more imprecise aspects, such as that it has a dense canopy or not, a columnar form or a wide-spreading form and so on.

It seems, again, to come down to a difference between experience and explanation. I can never experience your subjectivity, but why would that mean I can't explain how it comes about? — J

If you study the brain you can theorize about how it comes about, but that theory will never be provable, as is the case with most, if not all, scientific theories. The difficulty will be to explain why mind or consciousness seems intuitively to be the way it seems, and how could we ever demonstrate whether or not that "seeming" is veridical or not? It seems to me that whether it is veridical or not is the wrong question because the seeming stands on its own as what it is and cannot be compared with anything else. To try to do so seems like it would be a kind of category mistake. -

J

2.4kThe reason is that if we are standing in front of a tree we can point to its features and we will necessarily agree. — Janus

J

2.4kThe reason is that if we are standing in front of a tree we can point to its features and we will necessarily agree. — Janus

I understand what you're saying . . . but is it really so different? We are both "standing in front of" consciousness. We can point to its features. We may not necessarily agree, but I think that's too strong anyway, when it comes to trees. We're likely to agree that the bark is smooth, but maybe not. We're much more likely to agree about something measurable, such as the tree's diameter. But again, compare with consciousness: We'll probably agree that each of us conscious at the moment. I'll describe what happens when I imagine something; you'll compare and contrast. I describe how I tell the difference between a memory and a fiction, and you may well agree. We may find that perceptual experiences are necessarily the same. Etc. Is it really so unlike talking about a tree? We seek a common perspective.

Ah, but surely the big difference is that it's the same tree for you and me, but not the same consciousness. Hmm. Are we sure about that? Or to put it another way: If I have a sample of substance X before me, and describe its features, and you have a sample that may well be substance X as well, and you describe its features, and the descriptions match up -- are we going to end the discussion by saying, "But of course we can't be sure we're both really talking about the same thing"? I don't think so. Surely the burden of argument would go the other way: If my subjectivity is indeed not the same thing as yours (other than numerically), explain why not. What might cause such an odd circumstance to arise, given that we're both human beings who understand each other quite well, when it comes to consciousness-talk?

The difficulty will be to explain why mind or consciousness seems intuitively to be the way it seems, and how could we ever demonstrate whether or not that "seeming" is veridical or not? — Janus

Yes, this is important. A genuine explanation of consciousness has to do more than explain how it coincides with brain activity, and why such activity is required -- thought that's a hard enough task. It also needs to explain why subjectivity is the way it is, or (as you prefer) the way it seems to us. And yes, the fact that we can put the question either way leads to your puzzle of whether, in this case, it makes any sense to even separate what seems from what is veridical.

But . . . couldn't we raise all the same questions about any phenomenon? The trees seem a certain way to us; but are they really that way? It's not clear what sense to make of such a question. Similarly, conscious experience tout court seems a certain way to us; but is subjectivity really that way? I don't know where to take that. All I know is that the question appears, to me, the same one we could ask about any of our experiences. The fact that it's about consciousness itself doesn't change that -- or at least I don't see how. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut doesn't it apply to any attempt at an objective viewpoint, not to viewing consciousness especially? — J

Wayfarer

26.1kBut doesn't it apply to any attempt at an objective viewpoint, not to viewing consciousness especially? — J

Notice that Adam Frank specifcally refers to broad philosophical questions: 'there is a whole class of problems that are at the very root of some of our deepest questions, like the nature of consciousness, the nature of time, and the nature of the universe as a whole.' My reading is that in all these cases, we're thinking about something that can't be treated in an objective manner, because we're not outside or apart from what we're thinking about.

We are outside of or apart from the subjects of the natural sciences. As Frank says, 'billiard balls' - and a whole bunch more, up to and including space telescopes - all of these are matters of objective fact. Less so for the social sciences and psycbolpgy. Perhaps not at all for philosophy.

The phenomenology I'm reading is very much concerned with this, but reference to it is hardly found in English-language philosophy. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt's not a matter of strictly rational, i.e. non-empirical, theories being true or false, but of their being able to be demonstrated to be true or false. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.1kIt's not a matter of strictly rational, i.e. non-empirical, theories being true or false, but of their being able to be demonstrated to be true or false. — Janus

The only way the veracity of philosophical arguments is demonstrable is through their logical consistency and their ability to persuade. But they can't necessarily be adjuticated empirically. Case in point is 'interpretations of quantum physics'. They are not able to be settled with reference to the empirical facts of the matter. -

Janus

18kThe only way the veracity of philosophical arguments is demonstrable is through their logical consistency and their ability to persuade. But they can't necessarily be adjuticated empirically. Case in point is 'interpretations of quantum physics'. They are not able to be settled with reference to the empirical facts of the matter. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kThe only way the veracity of philosophical arguments is demonstrable is through their logical consistency and their ability to persuade. But they can't necessarily be adjuticated empirically. Case in point is 'interpretations of quantum physics'. They are not able to be settled with reference to the empirical facts of the matter. — Wayfarer

Exactly, that is just what I'm always saying in my discussions with you. The only point I would challenge would be that persuasiveness could be thought to be a good measure of veracity. The question would be "persuasive to whom?".

In any case the point about arguments (presuming logical consistency which really says nothing about truth) that are not decidable in any terms other than persuasiveness is that their ability to elicit belief or disbelief is a subjective matter. Again that says nothing at all about the truth or falsity of such an argument.

When it comes to beliefs that cannot be proven or empirically demonstrated to be true or false, a better measure, which could perhaps be empirically investigated, might be whether or not holding such a belief was beneficent or maleficent in terms of inducing flourishing and happiness or stagnation and unhappiness. But again, that might depend heavily on the diverse dispositions of different individuals. -

Janus

18kIf my subjectivity is indeed not the same thing as yours (other than numerically), explain why not. What might cause such an odd circumstance to arise, given that we're both human beings who understand each other quite well, when it comes to consciousness-talk? — J

Janus

18kIf my subjectivity is indeed not the same thing as yours (other than numerically), explain why not. What might cause such an odd circumstance to arise, given that we're both human beings who understand each other quite well, when it comes to consciousness-talk? — J

Interesting question. Given that the brain is the most complex thing known, our consciousness may possibly be very different, but it's impossible to determine other than by subjective reports, and given the generality of sharing the same language differences might be glossed over.

In any case we were discussing, not how consciousness seems to us, but whether or not it is conceivable that there could be a completely satisfying explanation as to how the brain produces consciousness (if it does). By contrast we have a very good model of how seeds develop into trees, but even there there are gaps. No one really knows how DNA could have a blueprint that alone determines morphology, and that is an interesting area currently being investigated by Michael Levin, who proposed the ingression of intelligence from what he calls a platonic space that is not a part of the physical world. The truth of such an idea would seem to be impossible to determine though...like, for example the multiverse hypothesis.

But . . . couldn't we raise all the same questions about any phenomenon? The trees seem a certain way to us; but are they really that way? — J

As you go on to say, it's hard to make sense of such a question. And the same could be said about how consciousness seems. At least with the tree we have well researched, cogent models that explain how it reflects light, which enters the eye...and so on...you know the story. On the other hand we say we know how consciousness seems, and give accounts of that, but how can we tell whether language itself is somehow distorting the picture via reification? How would consciousness seem to us if we were prelinguistic beings? That's obviously a rhetorical question.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum