-

The Great Whatever

2.2k

The Great Whatever

2.2k

Merely because we know some truth, namely that we are mistaken? Or is this the stronger claim that we must perceive real things in some sense to know that we are mistaken at some point (by comparing what is real to what we thought we perceived)? If the latter, this seems not to hold, since we can know we're mistaken, because our claims are internally contradictory or stifled by internal evidence having nothing to do with having any veridical perceptions, yet we might still never have any veridical perceptions (and even possibly know this).

I don't think the argument from illusion even has anything to do with the OP. It's just a mistake I made about what TGW was saying. — Mongrel

I think I mistook what was meant by 'argument from illusion.' -

Mongrel

3kOr is this the stronger claim that we must perceive real things in some sense to know that we are mistaken at some point — The Great Whatever

Mongrel

3kOr is this the stronger claim that we must perceive real things in some sense to know that we are mistaken at some point — The Great Whatever

I think any argument for indirect realism is going to assume internalism: one can only be said to know P if one has access to some justification for P.

Where P is "The pencil looks bent, but it's not.", the justification is probably an empirical/rational combo. Could there be a purely rational justification for knowing one's fallibility?

I think Hume would say no. No ontological argument can be purely apriori. I think Leibniz would say yes. Old-school rationalism always orbited divinity. I think the contemporary version would be some sort of panpsychism.... so if you believe in purely rational justifications for ontological statements... you probably already think the universe has the character of a dream. -

jkop

991

jkop

991

You have the same problem because ocular phenomena are hardly less representational than sense-data.you still have to come up with an explanation for hallucination, claiming that it's a real perception not of sense-data, but of a misleading ocular phenomenon, or something like that. But then we just have the same problem, rewritten without sense data: how do we know that all of our perceptions are not just of these misleading ocular phenomena and not of what we think they are? — The Great Whatever

It is not an ocular phenomena that we see in the case of an illusion but the real behaviour of light, as in refraction, or real shaded shapes, as in Mach-bands. In Mach-bands we see grey shapes as they are, but exaggerate the contrasts between the greys. The exaggeration is a use of the greys that we see, a way to organize them, but which is incorrectly passed for something present in our eyes or minds, yet absent somehow. But absent things are not present, neither in your eyes, nor inside your head. A memory of something absent does not possess parts of what it is a memory of.

In the case of hallucinations nothing is seen. The hallucinatory experience is not an impression evoked by, nor referring to, some synaptic screw-up; it is the screw-up that is experienced directly. Like the mind's organization of Mach-bands the mind attempts to make sense of the hallucinatory mess caused by drugs, disease, fatigue etc., by evoking "perceived" things despite their absence, hence 'hallucination'. It is simply incorrect to pass hallucinations for perceptions. -

Janus

17.9kI think Hume would say no. No ontological argument can be purely apriori. I think Leibniz would say yes. Old-school rationalism always orbited divinity. I think the contemporary version would be some sort of panpsychism.... so if you believe in purely rational justifications for ontological statements... you probably already think the universe has the character of a dream. — Mongrel

Janus

17.9kI think Hume would say no. No ontological argument can be purely apriori. I think Leibniz would say yes. Old-school rationalism always orbited divinity. I think the contemporary version would be some sort of panpsychism.... so if you believe in purely rational justifications for ontological statements... you probably already think the universe has the character of a dream. — Mongrel

This is a really nice point, well explained, Mongrel. 8-) -

The Great Whatever

2.2kIt really doesn't matter. Now the question is just about whether you're seeing merely light or the object.

The Great Whatever

2.2kIt really doesn't matter. Now the question is just about whether you're seeing merely light or the object.

If you say you see nothing in a hallucination, then the question is just whether for any case you are really seeing anything or not, since the same experience can be one of seeing something or seeing nothing, and you aren't able in principle to distinguish between the two.

None of these rhetorical moves are ever going to work, because they all have the same structure. -

jkop

991Now the question is just about whether you're seeing merely light or the object. — The Great Whatever

jkop

991Now the question is just about whether you're seeing merely light or the object. — The Great Whatever

Your question makes no sense, because when we see the object we also see the light it reflects, not either light or the object. We can also see emitted light without seeing an object, e.g. a flashlight, that emits it.

Hallucinations are hardly as recalcitrant, continuous, and non-detachable as the objects of veridical cases of perception. The existence of sense-data is not disvovered by having experiences, they're blindly assumed in the representationalist doctrine according to which we never see objects and states of affairs directly.the same experience can be one of seeing something or seeing nothing, and you aren't able in principle to distinguish between the two. — The Great Whatever

They work when you let go of representational perception. Also direct realists account for dreams, imagination, illusions, hallucinations etcNone of these rhetorical moves are ever going to work, because they all have the same structure — The Great Whatever

. -

The Great Whatever

2.2kYour question makes no sense, because when we see the object we also see the light it reflects, not either light or the object. We can also see emitted light without seeing an object, e.g. a flashlight, that emits it. — jkop

The Great Whatever

2.2kYour question makes no sense, because when we see the object we also see the light it reflects, not either light or the object. We can also see emitted light without seeing an object, e.g. a flashlight, that emits it. — jkop

I was only responding to the way you worded your post.

Hallucinations are hardly as recalcitrant, continuous, and non-detachable as the objects of veridical cases of perception. — jkop

The whole point is that you don't know that, because you haven't antecedently figured out that all, or any particular, perception is not an illusion.

The existence of sense-data is not disvovered by having experiences, they're blindly assumed in the representationalist doctrine according to which we never see objects and states of affairs directly. — jkop

It doesn't matter. Your arguments will not go through whether sense data are assumed or not, or whether they're real or not. What is blind, if anything, is the realist assumptions you are making. -

Michael

16.8kAlso direct realists account for dreams, imagination, illusions, hallucinations etc — jkop

Michael

16.8kAlso direct realists account for dreams, imagination, illusions, hallucinations etc — jkop

The point that's being made is that those things that we consider to be veridical experiences might actually be as false or as misleading (or however you want to phrase it) as dreams, illusions, hallucinations, etc. -

jkop

991

jkop

991

Look, there is no need to first figure out what a veridical perception should look like; perceptions are not somehow comparable representations from which we'd know whether a current perception isn't an illusion. The real object that you perceive looks as it is, not like something else, and unlike illusions the real object won't suddenly appear or disappear as you move around it etc.. It is not difficult to identify whether something passed for an object of perception is an illusion or a real object that one sees.. . you don't know that, because you haven't antecedently figured out that all, or any particular, perception is not an illusion. — The Great Whatever -

jkop

991

jkop

991

..and that point arises from the false assumption that there exists something (e.g. sense-data, phenomena etc.) by way of which all things are experienced. It explains away the possibility of things being experienced as they are, and thus it muddles up perception of real things with dreams, illusions, hallucinations etc..The point that's being made is . . . — Michael -

The Great Whatever

2.2kAgain, you don't know that, because you don't know which experiences are illusory versus veridical to begin with.

The Great Whatever

2.2kAgain, you don't know that, because you don't know which experiences are illusory versus veridical to begin with. -

The Great Whatever

2.2kNo it doesn't. As I already showed, the problem doesn't arise from a representational view of perception, nor from the existence of sense data. A direct realist must also admit that he can be mistaken about what he sees. If during a hallucination one sees nothing, then he does not know for any given experience whether he is seeing something or nothing, unless he antecedently assumes what was to be shown.

The Great Whatever

2.2kNo it doesn't. As I already showed, the problem doesn't arise from a representational view of perception, nor from the existence of sense data. A direct realist must also admit that he can be mistaken about what he sees. If during a hallucination one sees nothing, then he does not know for any given experience whether he is seeing something or nothing, unless he antecedently assumes what was to be shown. -

apokrisis

7.8kIn Mach-bands we see grey shapes as they are, but exaggerate the contrasts between the greys. The exaggeration is a use of the greys that we see, a way to organize them, but which is incorrectly passed for something present in our eyes or minds, yet absent somehow. But absent things are not present, neither in your eyes, nor inside your head. A memory of something absent does not possess parts of what it is a memory of. — jkop

apokrisis

7.8kIn Mach-bands we see grey shapes as they are, but exaggerate the contrasts between the greys. The exaggeration is a use of the greys that we see, a way to organize them, but which is incorrectly passed for something present in our eyes or minds, yet absent somehow. But absent things are not present, neither in your eyes, nor inside your head. A memory of something absent does not possess parts of what it is a memory of. — jkop

Don't Mach bands both strengthen and weaken the case for idealism?

They strengthen it in proving there are perceptual illusions we "can't wake up from". We can't unsee the Mach bands even if we believe (from the neuroscience) they are psychologically constructed. So reality is a perceptual illusion (well, perceptual process) from the get-go.

And we know that from colour perception too. What we experience resembles "nothing" about the stimulus.

On the other hand, Mach bands, colours and other perceptual illusions are utterly reliable in their usefulness. They do tie us to the world in what seems like a pragmatically factual fashion. We wouldn't really want to "wake up" if they are a dream as the evolutionary efficiency of our discriminatory abilities is also something we can believe in.

Dreams and other hallucinatory states are by contrast unreliable states of perception and not useful in any known fashion. It is not hard to see them as dysfunctional (although dreaming causes few problems as it is not remembered and the body is normally paralysed so we can't act on our visions).

So in being fictional - or rather symbolic - the brain's perceptual illusions are desirable precisely because they are idealistic rather than realistic. They begin the business of action-oriented conception from the get-go, right out at the retina or cochlear.

The homuncular "we" who is suppose to be watching the raw data as it eventually makes its way to "display central", the theatre of consciousness, has already been replaced by the mental habit which is a useful interpretation or model baked in as neural wiring. Right out at the eyeballs, the essential business of "not seeing reality" has started. Instead we are already "seeing", or conceiving, of shapes, motions, colours, sounds, scents - the "signs of things".

In short, the whole idealism vs realism debate gets hung up on the presumption that something veridical or representational is going on, when what is really going on is something functional or enactive.

So in this context, thank God for Mach bands. Reality is already unseeable except in terms of conceived signs. And also thank God for waking up. Our system of signs can't be fooled for long. In its functionalism, it has the means to sort its passing confusions out.

The whole point is that you don't know that, because you haven't antecedently figured out that all, or any particular, perception is not an illusion. — The Great Whatever

I thought the point was that hallucinations and dreams can be judged retrospectively. The long-run can be properly contrasted to the merely intermittent even in a purely internalist perspective.

Of course if what is at stake is whether reality can ever truly be known - even merely as a recalcitrant fact - then of course doubt is always possible about anything, if simply only because that is how intelligibility must work. To fully believe, there must be doubt to demonstrably dismiss.

Although here again pragamatism steers us back to the embodied view. Verbal doubt - claiming a formal possibility - is one thing. But real doubt is a real reluctance to act.

Again, the functional is what matters, the veridical is not a true concern here. -

Punshhh

3.5kAs I see it what the OP is thinking of is not whether idealism or realism is indicated, or supported. But rather the possibility that we, the personal self, might through some unknown, or veiled mechanism in our reality be able to be switched, or transferred to another reality, rather like we seem to be when we have a dream.

Punshhh

3.5kAs I see it what the OP is thinking of is not whether idealism or realism is indicated, or supported. But rather the possibility that we, the personal self, might through some unknown, or veiled mechanism in our reality be able to be switched, or transferred to another reality, rather like we seem to be when we have a dream.

I don't think an idealist ontology is required for this, there could just as well be "real" structures in our existence which are a mechanism for this to happen. For example a mechanism for the process of the transmigration of souls, enabling our "self" to be reborn in a newborn after our death. Or the mechanisms employed by enlightened beings to inhabit more than one place at a time, or walk between worlds, times. -

Michael

16.8k..and that point arises from the false assumption that there exists something (e.g. sense-data, phenomena etc.) by way of which all things are experienced. It explains away the possibility of things being experienced as they are, and thus it muddles up perception of real things with dreams, illusions, hallucinations etc.. — jkop

Michael

16.8k..and that point arises from the false assumption that there exists something (e.g. sense-data, phenomena etc.) by way of which all things are experienced. It explains away the possibility of things being experienced as they are, and thus it muddles up perception of real things with dreams, illusions, hallucinations etc.. — jkop

You're not addressing what's being said. You understand the conceptual difference between perception of real things and dreams/illusions/hallucinations/etc. The point being made is that we might not be having the former right now; only the latter. We might be trapped in the Matrix, we might be brains in a vat, we might be dreaming, etc. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe whole idealism vs realism debate gets hung up on the presumption that something veridical or representational is going on, when what is really going on is something functional or enactive. — Apokrisis

Wayfarer

26.1kThe whole idealism vs realism debate gets hung up on the presumption that something veridical or representational is going on, when what is really going on is something functional or enactive. — Apokrisis

I think your understanding is more aligned with the 'embodied cognition' approach of Maturana and Varela - that we're embedded in the 'umwelt', and we're actually continuous with it, in that brain/mind/body/environment, is a whole, whereas representative realism depicts 'the world' as something separate to 'mind', which somehow sunders reality at a non-existent joint. That is said by them to manifest as 'Cartesian anxiety' (also here.)

--

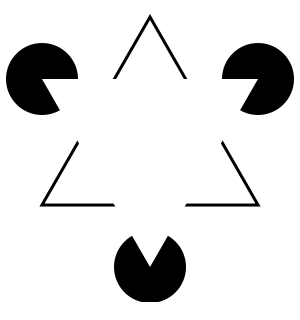

It's interesting to reflect on the notion of delusion as 'attributing wrong significance to what is seen', in contrast to illusion, which is 'seeing something which is not there'. This is a typical illusion:

Whereas a delusion is more deep-seated and harder to represent. (Think, for instance, of Trump's delusion of competence, and the delusion of those who also believe in his delusion.) Delusion is not something that can be easily represented, in the same way that an illusion can - in fact if you wanted to represent a delusion pictorially, you would have to couch it in some kind of symbolic or abstract form, rather than depicting an illusion per se.

I think, perhaps, those philosophies that depict worldly life as illusory, actually mean 'delusive'. For instance Hindu philosophy depicts worldly life as 'maya', which has the connotation of 'illusion' but which I think really means something more like 'a magic show' - like a drama in which the actors have forgotten that they are actually actors and so are mistaking the stage for reality. -

jkop

991the problem doesn't arise from a representational view of perception, nor from the existence of sense data. — The Great Whatever

jkop

991the problem doesn't arise from a representational view of perception, nor from the existence of sense data. — The Great Whatever

Then, despite your denials, it is obviously assumed that his experience represents either something or nothing, and that the object of his hallucinatory experience would be some element of the experience itself, i.e. sense-data, generated by synaptic screw-ups.If during a hallucination one sees nothing, then he does not know for any given experience whether he is seeing something or nothing, unless he antecedently assumes what was to be shown. — The Great Whatever

Direct realists don't make those assumptions about the nature of perceptions or experiences, so the epistemological problem is not the same.

In the illusion of a white triangle in Wayfarer's post above we see black shapes on a white background as they really are, and make use of what we see, perhaps by entrenched habits of how to organize what we see. We don't see the white triangle as it is not there, but we evoke an experience by organizing the things we do see, and confuse the evoked experience with an experience of seeing a triangle. -

The Great Whatever

2.2kThen, despite your denials, it is obviously assumed that his experience represents either something or nothing, and that the object of his hallucinatory experience would be some element of the experience itself, i.e. sense-data, generated by synaptic screw-ups. — jkop

The Great Whatever

2.2kThen, despite your denials, it is obviously assumed that his experience represents either something or nothing, and that the object of his hallucinatory experience would be some element of the experience itself, i.e. sense-data, generated by synaptic screw-ups. — jkop

Not at all. You merely must rather see something or nothing, which you have already admitted. -

Janus

17.9kWhat is blind, if anything, is the realist assumptions you are making. — The Great Whatever

Janus

17.9kWhat is blind, if anything, is the realist assumptions you are making. — The Great Whatever

I think what you are failing to see is that realist assumptions are not made on the basis of a belief that one possesses any knowledge of the "ultimate nature of things" or anything like that, but simply on the basis that when something is available to perception in common, that is when something is publicly available, then it is classed as real, in the sense of being concrete, and is understood to be logically independent of any particular percipient.

This is not to deny that I cannot know things like "I am thinking now" or "I am seeing X right now" without any body else being able to know that. The fact that I am thinking right now is undoubtedly the most concrete of experiences. But if I question whether I am really thinking, but am not instead merely dreaming that I am thinking; the distinction has no logical purchase because if I dream I am thinking then I must be thinking. But on the other hand if I question whether I am really seeing, but may not merely be dreaming that I am seeing, the distinction does, in accordance with the most fundamental qualities of our experience of dreaming and waking, have logical purchase.

So, we cannot genuinely escape the experience of seeing, and of knowing that we are seeing, things external to us, things that are not produced within our body/minds. Without that fundamental experience, our experience would not be experience at all, but would be unintelligible. The fact that it is possible in an attenuated, merely 'in principle' logical sense that I could be mistaken is irrelevant because if I am asked to give an account of how such an experience could be mistaken, any account I might be able to give always relies on the assumption of the reality of the external world, or at least of some external reality. -

apokrisis

7.8kI think what you are failing to see is that realist assumptions are not made on the basis of a belief that one possesses any knowledge of the "ultimate nature of things" or anything like that, but simply on the basis that when something is available to perception in common, that is when something is publicly available, then it is classed as real, in the sense of being concrete, and is understood to be logically independent of any particular percipient. — John

apokrisis

7.8kI think what you are failing to see is that realist assumptions are not made on the basis of a belief that one possesses any knowledge of the "ultimate nature of things" or anything like that, but simply on the basis that when something is available to perception in common, that is when something is publicly available, then it is classed as real, in the sense of being concrete, and is understood to be logically independent of any particular percipient. — John

Yes, the reason this debate is the hardiest of all perennials is that many simply do want to make absolutist claims. Or at least, have the strong desire to get as close as possible to that position

Then you are putting the middle-ground case for a pragmatic or epistemic realism, as against an ontic or naive realism. That is, all we can know in the end is that we seem to be talking about (and reacting to) the same things in the same ways.

And this is also a pragmatic or epistemic idealism in that it likewise rejects solipsism as credible belief. Instead we start already at the level of building belief based on the presumption of the existence of other like-minded minds. :) -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

Yes, I agree, in fact I don't think the very notion of 'ideas' can be intelligible without the assumption of things about which to have 'ideas', the natures of which are independent, not of thinking itself, but of any and all particular thoughts.

Also, i think naive realism does not consist in any absolutist claims, for the simple reason that I doubt that many naive realists would have thought their position through to such claims, and if they have then they would have realized that such claims are impossible to ground. So a considered naive realism is simply based on the fundamental logic of the experienced differences between waking and dreaming, veridical perception and hallucination.

The things we perceive publicly and reliably every day are 'really there' simply by virtue of the self-evident fact that they are reliably available for anybody to perceive. That's all it means to say something is really there with all its reliably perceptible qualities. Further metaphysical claims about structure or constitution do not contradict this naive realism, because whatever might be the final explanation for why and/or how things are really there for us, it cannot change the fact that they are. -

jkop

991It is trivially true that one either sees something or nothing, also in the case of hallucinations. It is not difficult to know whether one sees something or hallucinates.

jkop

991It is trivially true that one either sees something or nothing, also in the case of hallucinations. It is not difficult to know whether one sees something or hallucinates. -

apokrisis

7.8kSo a considered naive realism is simply based on the fundamental logic of the experienced differences between waking and dreaming, veridical perception and hallucination. — John

apokrisis

7.8kSo a considered naive realism is simply based on the fundamental logic of the experienced differences between waking and dreaming, veridical perception and hallucination. — John

A considered naive realism sounds oxymoronic. Do you simply want to avoid tagging yourself a pragmatist here?

That's fine, but pragmatism does come with its more specific commitments and the question is whether there is something in that which you dispute.

Also Wayfarer's phantom triangle seems still a good test of what folk actually believe. In what sense does it really exist - either as reality or idea?

All neurotypical humans would be expected to see a glowing bounded triangle that is "not really there".

So the naive realist has no problem counting cows in a field, or sitting on chairs that are physically present. But then they also have no problem thinking the cows are actually coloured, or the chairs are actually "solid stuff". This is why their realism is naive. It ignores a division by flip-flopping from objective to subjective ontic commitments without even realising it.

Gestalt illusions like Kanizsa's Triangle are nicely poised right at that critical divide. And so it becomes revealing exactly what answer the realist can give. Everyone sees the triangle. Everyone can have the neurological trickery explained. How should this combination of definite experience and inescapable trickery be resolved as a model of epistemology, a putative theory of truth?

This is where naive realists change the subject. But idealists also fail to do it justice on the whole. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

A considered naive realism does sound somewhat contradictory, granted. Of course a considered realism cannot be a truly naive realism, because in being considered it is no longer naive; but it might posit just the same as naive realism does; you know that there are objects that exist with all their qualities, independently of our individual minds. Of course their qualities, understood as perceptions, cannot be independent of perception, to say that would be to say something oxymoron; if not outright moronic.

I really can't see the issue with the triangle illusion apo, it exists as an image on a screen or on paper or as something, whatever doesn't really matter, that reliably gives us the impression of a triangle,but is not seen as a fully delineated triangle. In the same way an oak exists as an oak or as a cellular structure or as a molecular or atomic structure that is reliably seen as an oak.

What sort of pragmatist commitments do you have in mind that you think I might want to argue with? -

apokrisis

7.8kI really can't see the issue with the triangle illusion apo, it exists as an image on a screen or on paper or as something, whatever doesn't really matter, that reliably gives us the impression of a triangle,but is not seen as a fully delineated triangle. — John

apokrisis

7.8kI really can't see the issue with the triangle illusion apo, it exists as an image on a screen or on paper or as something, whatever doesn't really matter, that reliably gives us the impression of a triangle,but is not seen as a fully delineated triangle. — John

Yet you see an edge that is not physically there to complete the impression of a triangle. So there is now delineation that is a real visual difference and a delineation that is only a visual idea.

Whatever your epistemology, it must account for such a contrasting state of affairs within the one general point of view.

Naive realism is now to pretend there is no fact of the matter. So what does considered realism want to say? -

Janus

17.9kYet you see an edge that is not physically there to complete the impression of a triangle. So there is now delineation that is a real visual difference and a delineation that is only a visual idea. — apokrisis

Janus

17.9kYet you see an edge that is not physically there to complete the impression of a triangle. So there is now delineation that is a real visual difference and a delineation that is only a visual idea. — apokrisis

The difference between real delineation and the visual suggestion is that the first produces an actual image of a triangle, and the second produces a mere impression, that is the second does not produce an actual image; so the fact that the two different situations produce two different visual phenomena seems to be what you would expect and does not seem to me to indicate any problem or paradox that needs addressing. -

apokrisis

7.8kThe difference between real delineation and the visual suggestion is that the first produces an actual image of a triangle, and the second produces a mere impression, — John

apokrisis

7.8kThe difference between real delineation and the visual suggestion is that the first produces an actual image of a triangle, and the second produces a mere impression, — John

So in the first case, the self actually sees a representation, in the second, the self merely imagines that it sees this? Hmm.... -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

I am still not quite sure what you are getting at. When I look at the 'illusion' shown in Wayfarer's last post it is almost as though I can see the edges of the white triangle on the white background. I say "almost", though because when I look closely there are no edges there, which of course there couldn't be since it is just white on the same shade (presumably) of white.

It's no secret that the mind can sort of 'fill in' details where they 'normally' would be to produce a kind of impression. But you're not actually seeing the edges of the triangle except where there is black and white contrast. This is another example of an independently real phenomenon produced reliably by the action of visual data on human perceptual systems; and as such it supports the idea that something real independently of our individual perceptions, thoughts and minds is going on, something we do not fully understand and have no conscious control over. To admit this is not to admit idealism though, because idealism claims that percepts are not merely mediated and added to, but entirely constituted by, ideas. -

Michael

16.8kit supports the idea that something real independently of our individual perceptions, thoughts and minds is going on, something we do not fully understand and have no conscious control over. To admit this is not to admit idealism though, because idealism claims that percepts are not merely mediated and added to, but entirely constituted by, ideas. — John

Michael

16.8kit supports the idea that something real independently of our individual perceptions, thoughts and minds is going on, something we do not fully understand and have no conscious control over. To admit this is not to admit idealism though, because idealism claims that percepts are not merely mediated and added to, but entirely constituted by, ideas. — John

Epistemological idealists and other anti-realists can accept this, too. Their claim, though, is that the categories and kinds that we are familiar with and talk about are not categories and kinds that apply to these independently real things but to things as perceived, and which we then, as a matter of pragmatism (and often ontological naivety) project onto the independently real things as part of our world picture (as if things have a look even if they're not being looked at).

These independently real things are the noumena of Kant, the causally independent things of Putnam's internal realism, and so on.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum