-

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k

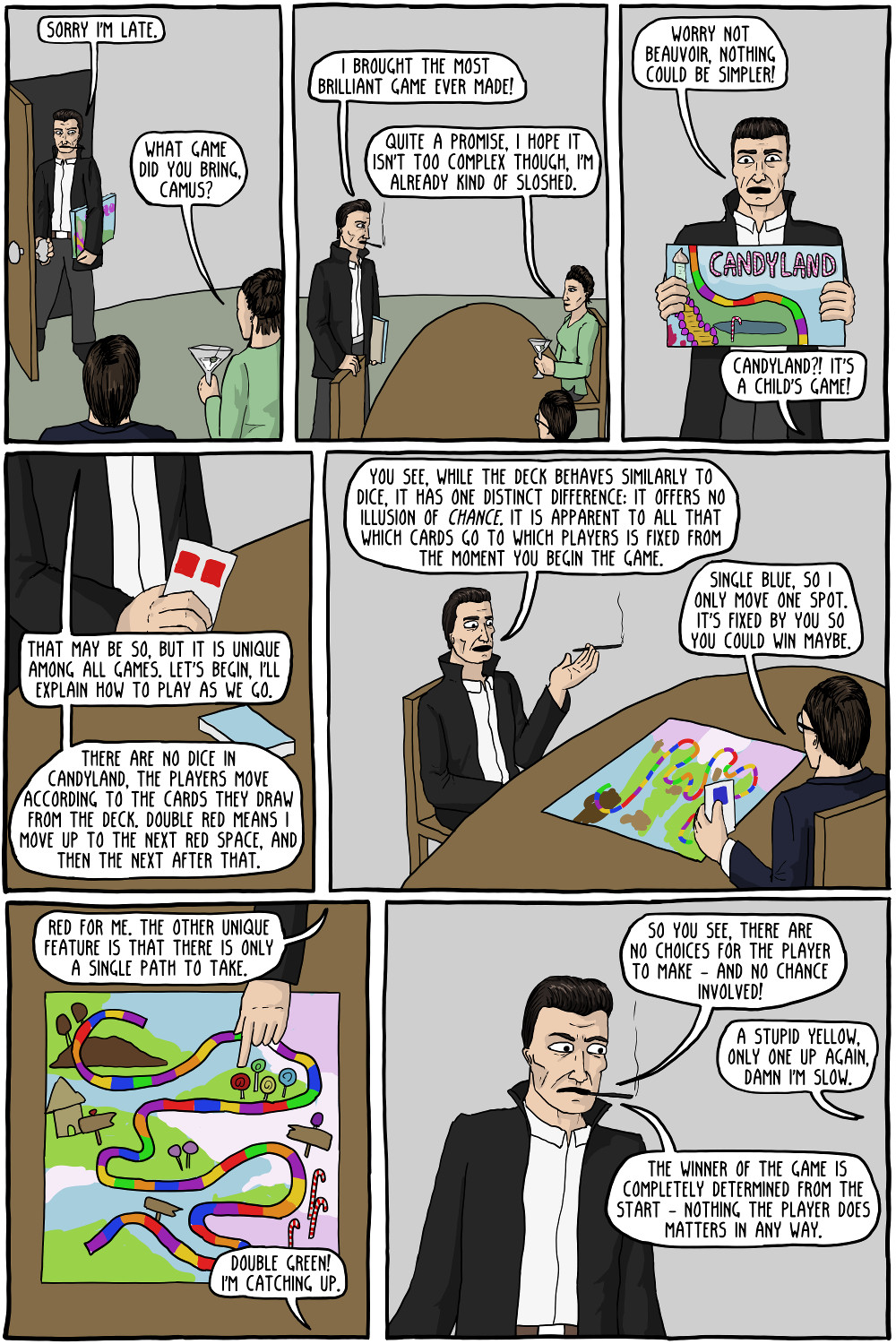

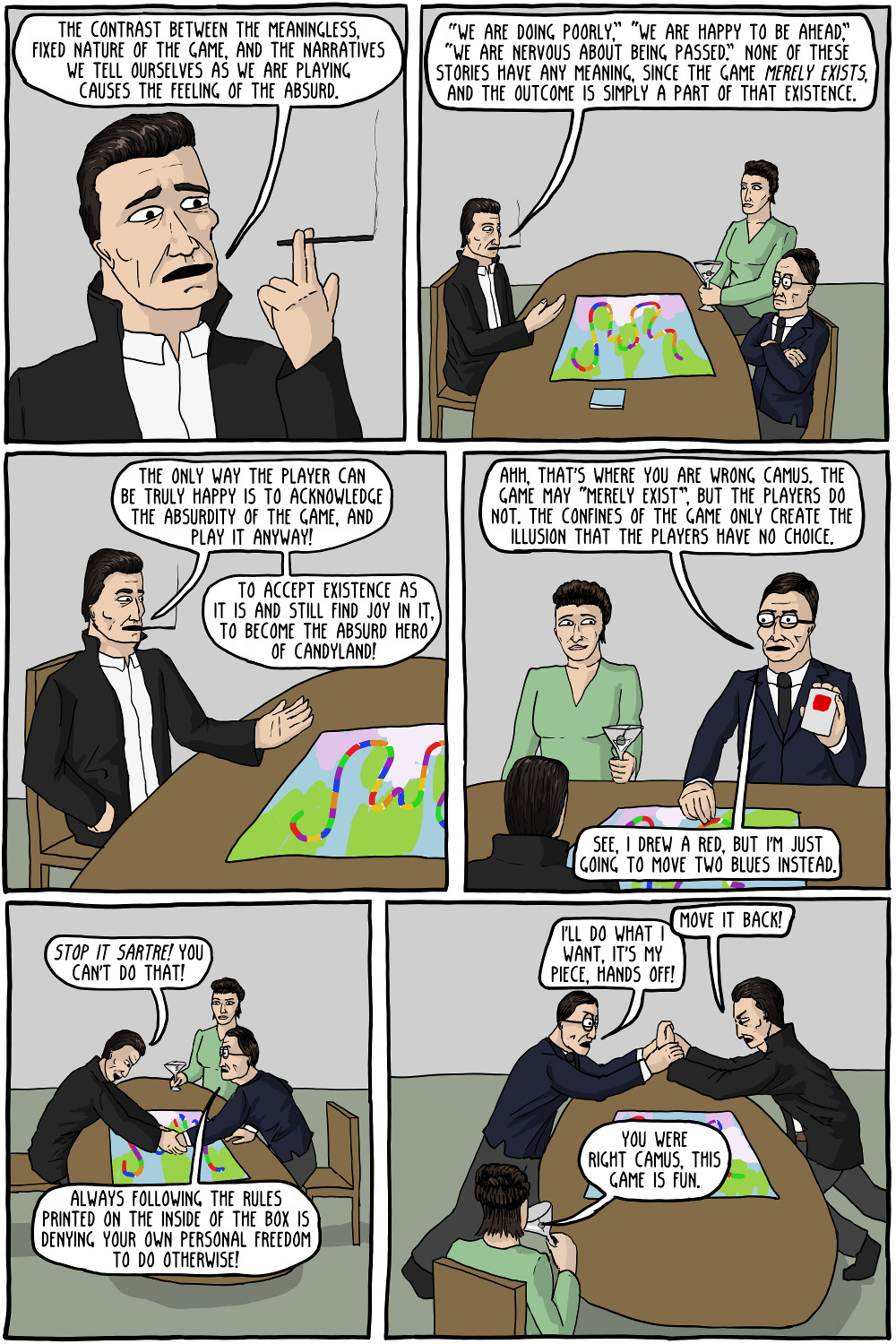

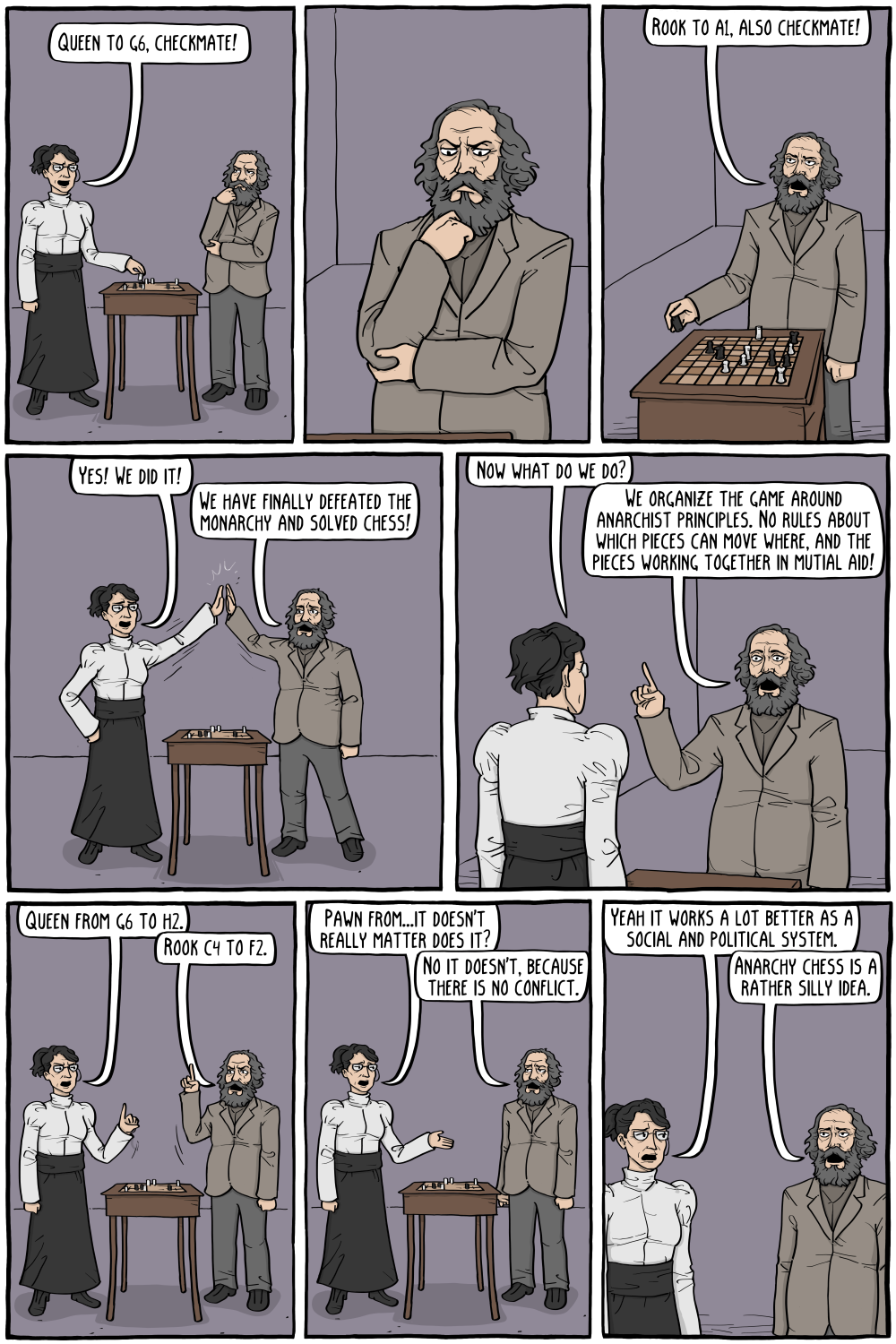

I can see how chess would be a useful example to hypericin's position. I think the problem is that chess is a voluntary activity, whereas morality is not ().

For example, you got out of bed this morning because you believed that the proposition, "I ought to get out of bed," was true. On my reckoning that is a moral judgment, pertaining to your own behavior. Is the reasoning that grounds that moral judgment purely hypothetical, with no reference to, or support from, objective values or 'oughts'? I really, really doubt it. When people make decisions they do so on the basis of the belief that some choices are truly better than others, in a way that goes beyond hypothetical imperatives. After all, in real life a hypothetical imperative needs to be grounded in a non-hypothetical decision or imperative in order to take flesh. -

Banno

30.6kYes, something along those lines. Any theory that requires differing senses of truth is to my eye dubious. I'd apply Searle's analysis, using status functions - "counts as" sentences. Moving along a diagonal "counts as" a move in chess, and so on. No need to re-think truth in order to play chess, which strikes me as a huge advantage.

Banno

30.6kYes, something along those lines. Any theory that requires differing senses of truth is to my eye dubious. I'd apply Searle's analysis, using status functions - "counts as" sentences. Moving along a diagonal "counts as" a move in chess, and so on. No need to re-think truth in order to play chess, which strikes me as a huge advantage.

I suspect neither of our interlocutors have the background to follow this discussion. -

Banno

30.6kAgain, that describes how people talk about truth but it doesn't in and of itself tell you if something is true or truthapt. — Apustimelogist

Banno

30.6kAgain, that describes how people talk about truth but it doesn't in and of itself tell you if something is true or truthapt. — Apustimelogist

Well, it was good enough for Tarski, Davidson and one or two others.

Nothing - any more than something stops someone from starting with g as 10m/s/s. Either way, they may find it difficult to maintain consistency. What makes it true that "g is 9.8m/s/s" is exactly that g is 9.8m/s/s.So what stops someone from starting from a different assumption about whether one ought to cause suffering? — Apustimelogist

Its very easy, you can talk about it in terms of things like goals, actions, their consequences and reason using them instead. People do it every day concerning the things they want to do and the ends they want to realize to decide what behaviors they want to do. — Apustimelogist

How do you set out the "ends they want to realize " without an evaluation? -

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, something along those lines. Any theory that requires differing senses of truth is to my eye dubious. I'd apply Searle's analysis, using status functions - "counts as" sentences. Moving along a diagonal "counts as" a move in chess, and so on. No need to re-think truth in order to play chess, which strikes me as a huge advantage. — Banno

Leontiskos

5.6kYes, something along those lines. Any theory that requires differing senses of truth is to my eye dubious. I'd apply Searle's analysis, using status functions - "counts as" sentences. Moving along a diagonal "counts as" a move in chess, and so on. No need to re-think truth in order to play chess, which strikes me as a huge advantage. — Banno

Quite right. Your post about chess-deductions made me thing of something similar, where any restrictions on the movement of the pawn depend on whether the pawn "counts as" a chess piece or just a piece of carved wood, and statements about chess pieces will have different truth conditions than statements about pieces of carved wood.

But if you and @hypericin engage one another on these points I will be interested to look on. -

hypericin

2.1kWe are apt to speak about the truth of an artifact according to the goal of the artist. So if there is a horse drawing competition, the drawing that most resembles a real horse will be the winner, and will be deemed truest. Or a carpenter's square is true when it achieves an exact 90° angle. — Leontiskos

hypericin

2.1kWe are apt to speak about the truth of an artifact according to the goal of the artist. So if there is a horse drawing competition, the drawing that most resembles a real horse will be the winner, and will be deemed truest. Or a carpenter's square is true when it achieves an exact 90° angle. — Leontiskos

You are just playing with words. This is not the same meaning as the "true" we are discussing.

This is really the whole of your argument, and it is nothing more than an assertion. Moreover, it is an assertion I have already addressed (↪Leontiskos). Feel free to engage that post. — Leontiskos

H If moral claims aren't true by virtue of moral rules/systems/etc, what are they true by virtue of? Is "one mustn't hurt cats" a brute fact, just as "one mustn't hurt dogs"? Or is there some rule they flow from?

And is everything that follows rules a tautology? The world, being orderly, must seem be a very tautological place to you.

You are saying that all truth is formal, deriving from axioms, and where axioms are not truth-apt so conclusions are not truth-apt (in the strong sense). — Leontiskos

I never said that. Moral claims may indeed be true, but only in that they are true representations of the moral system within which they operate. Just as propositions about chess may be true representations of the rules of chess, or not.

At the end of the day you just think prescriptions cannot be true or false, no? It is not that R is systematic/doctrinal/axiomatic, but rather that it is prescriptive. If all you are saying is that prescriptions are not truth-apt, then all that talk about systems and axioms led me to misunderstand your position. — Leontiskos

My point is to challenge the idea that

* people make moral propositional claims

- therefore

*moral propositional claims are truth-apt

- or

*everyone is running around making mistakes.

My argument is that there is a third way: people make propositional moral claims, but they are claims within systems of ideas, not claims about the world. And that you can make true or false, therefore truth-apt claims within systems of ideas which themselves may be true, false, not truth apt at all, or nonsensical.

The moral rules/systems I have in mind aren't necessarily prescriptions. They may be something like, "all sentient life has value". Indeed, I believe this. But, how do I know it? What tells me it is true? If it were false, how would I know it? How do I reality test it? How did I or anyone discover this fact? These are the questions that seem to bedevil any moral proposition, and it is in this sense that they aren't truth-apt: not only do we not know they are true, we don't even know what knowing they are true, or knowing they are false, looks like. -

hypericin

2.1k

hypericin

2.1k -

Michael

16.8kHow does one discover and verify such brute facts? — hypericin

Michael

16.8kHow does one discover and verify such brute facts? — hypericin

That is the key question that moral realists need to answer. Kant, for example, believed that this could be done using what he called pure practical reason, leading him to the categorical imperative.

Presumably you meant "...why there is something..." — hypericin

No, my point is that if moral facts are brute facts then there is no answer to the "why". But it is reasonable to ask the realist to prove "that" there are brute moral facts. -

Michael

16.8kThe problem is that's doesn't lead to the moral realism as a conclusion if you're a deflationist. — frank

Michael

16.8kThe problem is that's doesn't lead to the moral realism as a conclusion if you're a deflationist. — frank

My understanding of moral realism is that it is the theory that some moral propositions are true in such a way that if everyone believes that they are false then everyone is wrong.

Why can't a moral realist believe this and also be a deflationist? -

frank

19kMy understanding of moral realism is that it is the theory that some moral propositions are true in such a way that if everyone believes that they are false then everyone is wrong.

frank

19kMy understanding of moral realism is that it is the theory that some moral propositions are true in such a way that if everyone believes that they are false then everyone is wrong.

Why can't a moral realist believe this and also be a deflationist? — Michael

A moral realist can believe that and be deflationist. The point is, she started out a moral realist. She did not arrive there by way of argumentation.

The argument in question (that moral statements are truth apt) just has no force to persuade. If you're a moral realist, it's probably because it fits your psychological makeup. There is no argument for it. -

Michael

16.8kI'm a little confused. Are you saying that moral sentences aren't truth-apt or are you saying that moral sentences being truth-apt does not entail moral realism?

Michael

16.8kI'm a little confused. Are you saying that moral sentences aren't truth-apt or are you saying that moral sentences being truth-apt does not entail moral realism?

I'm not sure who would argue for the latter. Moral sentences being truth-apt also allows for error theory and moral subjectivism.

I'm also unsure of the relevance of being a deflationist. Even if one is a correspondence theorist or a coherence theorist it is still the case that moral sentences being truth-apt also allows for error theory and moral subjectivism. -

Bob Ross

2.6k

Bob Ross

2.6k

If you agree that there is a relevant difference between ice cream preference and not wanting babies to be tortured, then what is the difference!? How does a taste become justifiably imposable?

I answered this in detail in my response, and you can even find it in the quotes you have of me in your response. I said that the difference is that I care about it enough to impose it on other people, just like how you care enough about upholding moral facts to force that value down my throat.

You say, "This is a taste, but I do not treat it as a taste."

But I never said this. I would strongly urge you, with all due respect, to read my responses more carefully. I elaborated in detail how they are both tastes and are not different with regards to that...but whether it is considered ‘reasonable’ to impose is going to depend, since it is subjective, on how much the person cares about it—and I gave the analogy in axiology that commits you to the same line of thinking.

You claim they are tastes, but you treat them as laws. This is irrationality at its finest.

If by ‘law’ you mean ‘moral facts’, then you have simply misapprehended everything I have proposed so far. If by ‘law’ you just mean a ‘subjective moral judgment that commits the person to trying to universalize a desire’, then obviously I agree with that. However, the irrationality you refer to only holds water if you are speaking about ‘law’ in the former sense, not the latter.

Onto the irrationality:

It is irrational to impose tastes

Why? What’s irrational about it? Show me a contradiction, whether that be logical, actual, or metaphysical. I don’t think you can: you just projecting your sentiment that we shouldn’t impose tastes as if it ‘irrational’.

Likewise, you refuse to respond to my hypothetical that I have presented now multiple times and I am starting to think you may realize it undermines your point here; otherwise, I don’t know why you keep evading it. Respond to the hypothetical.

it is irrational to hold that there are non-objective truths

I never made this claim. Again, I think a lot of this is just misunderstandings on your side, and perhaps I am just not conveying it good enough: it is a fact that I believe, I disapprove, of torturing babies, but that is not a moral fact. The moral judgment is enveloped in the belief, which is an upshot of my psychology and physiology, that is a projection my thinking and not something which latches onto a fact about the world. You seem to be thinking that I am saying that if I believe that one shouldn’t torture babies that it is true: this is ambiguous: it is not true that ‘one should not torture babies’ because it is it true that ‘I believe one should not torture babies’. There is no truth of the matter about ‘one should not torture babies’, since there is no fact of the matter. But it is entirely possible for “I believe ...” to be true for me and false for you since it is an indexical statement. So where’s the irrationality in this? Show me a contradiction.

it is irrational to treat two alike tastes entirely differently

Sort of true. If they are identical, then sure I agree. But they aren’t. You are assuming we should treat them the same because they are within the same category, but that doesn’t make them identical. I care much more for one taste than another, then it rationally makes sense to prioritize the former over the latter. Show me the contradiction.

it is irrational to claim that rationality is a subjective matter

What makes something rational is not subjective in the sense that we get to make them up. What is ‘rational’ is tied to epistemology, which is operated under the context of ‘if one wants to know the world, then they should...’ (type hypothetical imperatives) and, thusly, within that context there are objectively better ways to know the world and, extensionally, better ways to be rational. I never claimed that the term ‘rationality’ was grounded in subjectivity: I think that it is, more or less, about ‘aligning oneself with reality in thought and action’.

When faced with a contradiction in your thinking you try to defend it, and seven more pop up.

You have not come up with a single valid contradiction yet. Give me two propositions which I affirm and demonstrate the contradiction or incoherence with them. -

frank

19kAre you saying that moral sentences aren't truth-apt or are you saying that moral sentences being truth-apt does not entail moral realism?

frank

19kAre you saying that moral sentences aren't truth-apt or are you saying that moral sentences being truth-apt does not entail moral realism?

I'm not sure who would argue for the latter. Moral sentences being truth-apt also allows for error theory and moral subjectivism. — Michael

Moral statements being truth apt doesn't entail moral realism. If I hold that the truth predicate merely serves a social function, I can accept the truth aptness of moral oughts without any metaphysical implications. I may also reject scrutability of reference, so I don't think "ought" refers any more than any other word. This doesn't interfere with truth aptness. -

hypericin

2.1kThat is the key question that moral realists need to answer. Kant, for example, believed that this could be done using what he called pure practical reason, leading him to the categorical imperative. — Michael

hypericin

2.1kThat is the key question that moral realists need to answer. Kant, for example, believed that this could be done using what he called pure practical reason, leading him to the categorical imperative. — Michael

But then it is no longer a brute fact, no? The categorical imperative explains why one ought not to X. Or are you saying the categorical imperative itself is the brute fact, for Kant. -

hypericin

2.1kFor example, you got out of bed this morning because you believed that the proposition, "I ought to get out of bed," was true. On my reckoning that is a moral judgment, pertaining to your own behavior. — Leontiskos

hypericin

2.1kFor example, you got out of bed this morning because you believed that the proposition, "I ought to get out of bed," was true. On my reckoning that is a moral judgment, pertaining to your own behavior. — Leontiskos

Generally not. "I ought to get out of bed because otherwise I will be late for work" is not a moral judgement, it is purely pragmatic. Only something like "I ought to get out of bed because I shouldn't be lazy" approaches a moral claim.

I don't follow your point. Making moral claims seems voluntary, one is under no obligation to make them. And I don't see why voluntary/necessary is an important distinction in this discussion. -

Apustimelogist

946

Apustimelogist

946

For example, you got out of bed this morning because you believed that the proposition, "I ought to get out of bed," was true. On my reckoning that is a moral judgment, pertaining to your own behavior. — Leontiskos

Well, I would call it a normative judgement rather than moral judgement, but maybe thats a tangential point.

Is the reasoning that grounds that moral judgment purely hypothetical, with no reference to, or support from, objective values or 'oughts'? I really, really doubt it. — Leontiskos

I don't agree. "I ought to get out of bed" is not independent of the context. Sure, you can incorporate the context and say "I ought to get out of bed in x context" but then that leads me to ask why I ought to get out of bed in x context. I don't see how such a reason cannot depend on my personal desires and personal goals.

I will then end up asking the question: "why ought I perform behaviors that fulfil my goals?". I see no putatively objective statement about the world that makes it true that "I ought to fulfil my goals". I may want to fulfil my goals but I don't see why that means I ought to behave in accordance to what I want. Yes, it may seem a little strange or irrational (to most people) if I don't act in accordance to my own goals but I don't see why those consequences mean I ought to fulfil my goals. So what if it is strange or seems to be irrational to others? Attempts to establish why I shouldn't behave irrationally just seem to appeal to the same kinds of normative statement at the beginning of this paragraph: " I ought to fulfil my goals" or "I ought to do what I want".

Just giving such normative statements as a brute fact doesn't seem good enough justificafion for me because there is nothing stopping someone from starting from different assumptions and believing a different kind of contradictory normative fact. Neither is there any fact of the world that will distinguisg which of the contradictory normative facts are actually true. It seems to come down to subjective intution and my views of neuroscience and cognition do not give me any reason to believe that such subjective intuitions have any link to some objective reality in regard to normative oughts.

When people make decisions they do so on the basis of the belief that some choices are truly better than others, in a way that goes beyond hypothetical imperatives. — Leontiskos

I don't doubt this since there are many examples of these people in these threads but I think thats beside the point. Someone believing that one is performing choices that are objectively good or bad doesn't give necessarily give me reason to think those beliefs are in some sense veridical, especially when some people might not share those beliefs. When I try to directly examine reasons for there to ve objective oughts as I have just done in the last section, I do not come up with any reason that they actually exist.

After all, in real life a hypothetical imperative needs to be grounded in a non-hypothetical decision or imperative in order to take flesh — Leontiskos

I am not totally sure what you mean here but I am guessing you mean that these imperatives need to be grounded in the kinds of prior assumptions like "I ought to fulfil my goals" which I could not find any objective basis for in a previous section of this post.

Probably far too liberal useage of italics in this post, unfortunately. -

hypericin

2.1kI agree with that. It could be that error theory of moral subjectivism are correct. — Michael

hypericin

2.1kI agree with that. It could be that error theory of moral subjectivism are correct. — Michael

Or there could be no such true brute facts such as the categorical imperative. Or, such ultimate moral propositions may not be truth-apt, while everyday moral claims, being claims about such ultimate propositions, are perfectly truth apt. -

Michael

16.8kOr there could be no such true brute facts such as the categorical imperative. Or, such ultimate moral propositions may not be truth-apt, while everyday moral claims, being claims about such ultimate propositions, are perfectly truth apt. — hypericin

Michael

16.8kOr there could be no such true brute facts such as the categorical imperative. Or, such ultimate moral propositions may not be truth-apt, while everyday moral claims, being claims about such ultimate propositions, are perfectly truth apt. — hypericin

That would be moral subjectivism?

Although I would argue against moral subjectivism on the grounds that when we make moral claims we don't usually think of ourselves to be just expressing a subjective opinion. This is why there is such a strong disagreement. When I say that X is good and you say that X is bad, you don't tell me that it might be good for me; you tell me that I'm wrong.

Rightly or wrongly we mean to assert an objective moral fact, and as such it must be that either moral realism or error theory is correct. -

Apustimelogist

946Well, it was good enough for Tarski, Davidson and one or two others. — Banno

Apustimelogist

946Well, it was good enough for Tarski, Davidson and one or two others. — Banno

Well every single opinion is good enough for someone even if has valid criticisns so I don't really see what this statement contributes any defence.

Nothing - any more than something stops someone from starting with g as 10m/s/s. Either way, they may find it difficult to maintain consistency. What makes it true that "g is 9.8m/s/s" is exactly that g is 9.8m/s/s. — Banno

Well then you have not given an argument. Giving an argument would be giving me some evidence that "g is 9.8m/s/s" or the equivalent for some moral statement.

How do you set out the "ends they want to realize " without an evaluation? — Banno

I assume by this you mean that statements like "Banno likes Vanilla" supposedly cannot be true.

"Banno likes vanilla" is very different from "Banno ought to eat vanilla" though. "Banno likes vanilla" is not a normative statement, it is a fact about states of the world insofar as you are a component of the world and "liking" is a state of your being. There is nothing wrong with that.

At the same time, I don't see why people can't reason using normative statements even if those statements don't necessarily have objective truth values. I don't see why the fact that I can reason with them implies objective truth, similarly to rules in chess.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum