-

frank

18.9kDeflationary accounts of truth (such as disquotationalism or prosententialism) stress the pragmatic function of "truth" predicates while denying that truth is a property of the propositions they are predicated of. This sort of pragmatism about truth is somewhat different from the pragmatism of, say, Richard Rorty, who claims that what makes a belief "true" is nothing over and above the fact that believing it is useful. It is this latter form of pragmatism that you may be thinking of. Yet, there is an affinity between those two sorts of pragmatism. (Robert Brandom, who was a student of Rorty, defended a form of prosententialism.) — Pierre-Normand

frank

18.9kDeflationary accounts of truth (such as disquotationalism or prosententialism) stress the pragmatic function of "truth" predicates while denying that truth is a property of the propositions they are predicated of. This sort of pragmatism about truth is somewhat different from the pragmatism of, say, Richard Rorty, who claims that what makes a belief "true" is nothing over and above the fact that believing it is useful. It is this latter form of pragmatism that you may be thinking of. Yet, there is an affinity between those two sorts of pragmatism. (Robert Brandom, who was a student of Rorty, defended a form of prosententialism.) — Pierre-Normand

I was just thinking of a broad deflationism following Frege's insights about the indefinability of truth.

However, suppose we grant you such a pragmatist conception of truth. The question regarding how "inner" perceptual states refer to "external" empirical facts about the world thereby gets translated into questions regarding the pragmatic function that enjoying such phenomenological states can serve. — Pierre-Normand

That would be true if I defined truth as usefulness, but that's not what I had in mind. Contemporary forms of indirect realism start with the assumption that we can rely on our perceptions of things like human anatomy and physiology. Representational models of human perception are natural developments from there.

But once we've noticed that perception can't be a passive process, were left wondering how far it goes and whether the whole issue becomes an ourobourous. That's where pragmatism comes in. Instead of abandoning the whole project because of the unknown, we carry on learning from this thing we've been calling the real world. We just do so with the knowledge in the background that we may be living in a dream. I don't think any of this intrudes on what scientists do.

Edit, btw, deflationists usually do accept that truth is a property of statements. -

hypericin

2.1kSorry for the late reply, I've been busy with work.

hypericin

2.1kSorry for the late reply, I've been busy with work.

The definition of indirect realism offered by ChatGPT states that our experiences (presumably our perceptual experiences) are mediated by mental representations or ideas. It contrasts this with "directly perceiving external objects themselves", i.e. direct realism. — Luke

The quote from ChatGPT:

It posits that our experiences of the world are mediated by mental representations or ideas, rather than directly perceiving external objects themselves.

"Experience" here is certainly not what we have been calling "perceptual experiences", aka qualia. Merriam-Webster's definition of experience:

the fact or state of having been affected by or gained knowledge through direct observation or participation

In other words, our contact with the world is mediated by mental representations or ideas. This is indirect realism. Not "that our perceptual experiences of external objects are mediated by mental representations or ideas". I can't even make much sense of that formulation, let alone defend it. Perceptual experience is the mediation between the self and the world, and is a mental representation.

Reading through the GPT definition, I see little substantive difference with my own.

You seem to agree with the direct realist that perceptual experience of external objects is direct (or you don't appear to argue for an intermediary between them). — Luke

Perceptual experience is "direct", because there is no intermediary between the self and perceptual experience, not because there is no intermediary between perceptual experience and external objects. Again, perceptual experience is the intermediary.

However, if your perceptual experience is, e.g., the taste of strawberries, then is your awareness of the taste of strawberries different to your perceptual experience of the taste of strawberries? — Luke

The "taste" and the "awareness of the taste" verbally designate parts or aspects of what may be the same thing: the perceptual experience of tasting strawberries. As I've said before, my argument does not hinge on these being ontologically distinct things.

The perceptual experience mediates the awareness of the strawberry. Not of the taste.How does the perceptual experience mediate the awareness? — Luke

You said earlier that a perceptual experience entails awareness of that perceptual experience; that it entails its own awareness. In that case, what does awareness of the perceptual experience add to the perceptual experience that the perceptual experience itself lacks? — Luke

It only points out the awareness. I regard "awareness of the strawberry is mediated by awareness of the taste of strawberry" and "awareness of the strawberry is mediated by the taste of strawberry" to be identical formulations. The word "awareness" is just a useful word sometimes, i.e. "I am aware of perceptual experience", instead of the confusing "I experience perceptual experience" or the ungrammatical "I am perceptual experience" and is preferable to "perceive" and "see", which have unwanted connotations.

However, if perceptual experiences are merely "representational" without being "representations" — Luke

How can something be representational without being a representation?

Direct perceptual experiences are representations.

The representations are of real objects.

Therefore, Direct perceptual experiences are representations of real objects.

and

"Direct perceptual experiencs" are of real objects

but not

"Direct perceptual experiences" are directly of real objects

I would rather say

"Direct perceptual experiences" are indirectly of real objects

because

Representational experience is indirect experience of the represented. -

AmadeusD

4.2kots of biological phenomena emerge from bio-chemical events (e.g. photosynthesis), so you'd need a good counter-argument with which you could reject the idea that conscious experiences emerge from brain states. — jkop

AmadeusD

4.2kots of biological phenomena emerge from bio-chemical events (e.g. photosynthesis), so you'd need a good counter-argument with which you could reject the idea that conscious experiences emerge from brain states. — jkop

You wouldn’t. They aren’t explaining the same things unless you take the evolution-only view of exprience (which is then post-hoc and hallucinatory). But if experience can be “real time” and veridical then I thinn the DR needs a better line.

All of what? — jkop

All of what you had just quoted. Which was a defense of DR. So your tone is odd here.

Furthermore, brain states are necessary for any conscious experience, veridical or hallucinatory, but this has little to do with the directness of perception, which is supposedly what you wish to reject. — jkop

It has a lot to do with it. If experience is to be veridical it must be directly caused by the objects it represents. But we know that’s factually not true. So ♂️ -

AmadeusD

4.2kThe content of the visual experience and the rain are inseparable in the sense that it is the visible property of the rain that determines the phenomenal character of the visual experience. The fact that they are separate things is beside the point. — jkop

AmadeusD

4.2kThe content of the visual experience and the rain are inseparable in the sense that it is the visible property of the rain that determines the phenomenal character of the visual experience. The fact that they are separate things is beside the point. — jkop

This is close to nonsensical.

The content of the visual experience is entirely separate from the rain itself. That much is clear. How one gets to the other is the question. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThat would be true if I defined truth as usefulness, but that's not what I had in mind. Contemporary forms of indirect realism start with the assumption that we can rely on our perceptions of things like human anatomy and physiology. Representational models of human perception are natural developments from there. — frank

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThat would be true if I defined truth as usefulness, but that's not what I had in mind. Contemporary forms of indirect realism start with the assumption that we can rely on our perceptions of things like human anatomy and physiology. Representational models of human perception are natural developments from there. — frank

I had presented a challenge for indirect realists to explain how the phenomenology of perceiving an apple to be within reach, say, can be deemed to be true to the facts (or a case of misperception) if the intrinsic features of the representation don't include such things as expectations that the apple can indeed be reached by the perceiver's outstretched hand. It is those expectations that define the truth conditions of the visual content, in this particular case.

There may indeed be some usefulness for purpose of neuroscientific inquiry to postulate internal "representations" on the retina or in the brain that enable the perceiver to attune their perceptual contents with their skills to act in the world. But those "representations" don't figure as objects directly seen by the perceivers. Just like those "upside down" retinal images, they are not seen by the embodied perceiver at all. They play a causal role in the enablement of the subjet's sensorimotor skills, but it is those (fallible) skills themselves that imbue their perceptual experiences with world-directed intentional purport. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIn the case that they do actually "flip around", is that simply the brain trying to revert back to familiarity? If so, a thought experiment I offered early in this discussion is worth revisiting: consider that half the population were born with their eyes upside down relative to the other half. I suspect that in such a scenario half the population would see when standing what the other half would see when hanging upside down. They each grew up accustomed to their point of view and so successfully navigate the world, using the same word to describe the direction of the sky and the same word to describe the direction of the ground. What would it mean to say that one or the other orientation is the "correct" one, and how would they determine which orientation is correct? — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIn the case that they do actually "flip around", is that simply the brain trying to revert back to familiarity? If so, a thought experiment I offered early in this discussion is worth revisiting: consider that half the population were born with their eyes upside down relative to the other half. I suspect that in such a scenario half the population would see when standing what the other half would see when hanging upside down. They each grew up accustomed to their point of view and so successfully navigate the world, using the same word to describe the direction of the sky and the same word to describe the direction of the ground. What would it mean to say that one or the other orientation is the "correct" one, and how would they determine which orientation is correct? — Michael

Thank you for pointing this out. I wasn't yet participating in the discussion back then. I've located this post of yours that you are making reference to.

You are suggesting that there is something inherent to phenomenology, or to the intrinsic content of our perceptual experiences, regarding what appears to us to be "up" or "down" (regardless of the names that we use to report on those directions), that somehow persists independently from subsequent attempts by the brain to "revert back to familiarity."

In your thought experiment, somehow, this relative inversion between the contents of the two species' (or genders') respective visual experiences is a feature of their "private" qualia and is initially caused by the orientation of their eyes. But what does it even mean to say that an animal was born with its eyes "upside down"? Aren't eyes typically, functionally and anatomically, symmetrical across the horizontal plane? And since our eyes are camera obscura that already map the external world to "upside down" retinal images, aren't all of our eyes already "upside down" on your view?

What if our eyes had evolved an extra set of lenses in them that would have the sole function of producing retinal images that are "the right way up". Would that change anything at all to our visual experiences? (I think Thomas Reid already had understood quite well why the inversion of our retinal images was irrelevant to the character of visual experience.)

(I asked Claude 3 Sonnet to rephrase the above in a more fluent way, and while it performed brilliantly and even volunteered insightful additional arguments, I don't 100% agree with all of its characterizations. So, I'm reproducing its suggested rewriting below, without fully endorsing it, since it may still clarify a few things.)

Claude 3 Sonnet reformulation/commentaryClaude 3 Sonnet:

Here's my attempt at reformulating your draft response in a more focused and incisive way:

"I appreciate you resurfacing this thought experiment about the hypothetical species with inverted eyes between the sexes. However, I think there are some problematic assumptions built into the scenario that need unpacking.

At the core, you seem to be suggesting that there is something inherent to visual phenomenology - the intrinsic "what it's like" of perceptual experience - that would be radically different between the two sexes solely due to the inversion of their eyes relative to each other. But what exactly is the basis for this assumption?

The mere fact that their eyes are oriented inversely doesn't necessarily entail that their experiences must thereby exhibit an innate, qualitative inversion in how "up" and "down" appear. After all, our own eyes present inverted retinal images, yet we don't experience the world as upside-down. The brain compensates for and discounts such differences at the subpersonal level.

What's more, we can undergo radical shifts in orientation - hanging upside down, doing somersaults, etc. - without our phenomenology fundamentally "flipping" in the way your thought experiment seems to require for the two sexes. Our experience remains stably oriented around up/down, despite dramatic changes in retinal stimulation and eye/head positions.

So you seem to be building in a further assumption - that the two sexes would be innately hard-wired for radically divergent qualia solely due to eye inversion. But this requires much stronger arguments that mere anatomy can somehow determine phenomenal character in such an overwhelming way, circumventing the possibility of neural compensation or re-alignment.

Importantly, you note that the two sexes would use the same words for "up" and "down" - suggesting at least some commonality in their grasp of objective spatial features and affordances. This coheres better with the disjunctivist view that perceptual content is grounded in shared embodied skills for environmental engagement, not purely internal qualia.

Rather than positing innate, incommensurable phenomenal perspectives, the disjunctivist can allow for differences in orientation and perspective-taking while still securing a common world disclosed through the exercise of mutually attuned abilities. Veridicality is a matter of successful environmental engagement, not matching qualitative experiences."

The key moves here are:

1) Pressing you on the core assumption that mere eye inversion alone would necessarily produce radically divergent phenomenologies

2) Noting how we can undergo radical shifts in orientation without such phenomenal "flipping"

3) Questioning the stronger assumption of innate, hard-wired differences in qualia

4) Highlighting how the shared linguistic practices suggest a more common experiential grasp of reality

5) Contrasting this with the disjunctivist's emphasis on shared embodied skills and environmental attunement as grounding objective purport

Let me know if you'd like me to modify or expand any part of this reformulated response. I tried to maintain the core of your objection while sharpening the focus on the key premises that need to be challenged or justified in Michael's thought experiment. -

Luke

2.7k"Experience" here is certainly not what we have been calling "perceptual experiences", aka qualia. — hypericin

Luke

2.7k"Experience" here is certainly not what we have been calling "perceptual experiences", aka qualia. — hypericin

Why "certainly not"? It's what I have been calling perceptual experiences, aka qualia.

Reading through the GPT definition, I see little substantive difference with my own. — hypericin

Did you note that the GPT definition differs from yours? The GPT definition of indirect realism does not state that our awareness is mediated by mental representations or ideas. Instead, the GPT definition states that our experiences are mediated by mental representations or ideas. The GPT definition contrasts this with "directly perceiving external objects themselves". I would consider the perceptual experiences of tasting, seeing, hearing, etc. to be experiences.

Also, the GPT definition states that we perceive perceptions; a point on which you have disagreed previously (my emphasis):

According to indirect realism, when we perceive the world, what we are actually experiencing are mental representations or perceptions that are caused by external objects. These mental representations are often considered to be in the mind and are distinct from the external objects they represent.

In other words, indirect realism suggests that we do not directly perceive external objects such as tables, chairs, or trees. Instead, we perceive representations or perceptions of these objects that are constructed by our senses and mental processes. This theory acknowledges that there is a real external world but asserts that our understanding and experience of it are indirect and mediated by mental representations. — GPT definition of indirect realism

The "taste" and the "awareness of the taste" verbally designate parts or aspects of what may be the same thing: the perceptual experience of tasting strawberries. As I've said before, my argument does not hinge on these being ontologically distinct things. — hypericin

Your argument hinges on the "taste" and the "awareness of the taste" being, at least, conceptually distinct things. That is, your argument hinges on your awareness of the object being distinct from your perceptual experience of the object. If your awareness of the object were indistinct from your perceptual experience of the object, then your awareness could no longer be mediated by your perceptual experience. You can't say that it doesn't matter if these are indistinct, because otherwise your position becomes direct realism. If the "taste" and your "awareness of the taste" were indistinct then there would be no intermediary and they would both be directly of the object.

In other words, you claim that we have indirect awareness of external objects because our awareness is mediated by our perceptual experience, but you also find no problem in collapsing the distinction between our awareness of our perceptual experience and our perceptual experience. If you collapse this distinction, then you lose the indirectness.

Direct perceptual experiences are representations.

The representations are of real objects.

Therefore, Direct perceptual experiences are representations of real objects.

and

"Direct perceptual experiencs" are of real objects

but not

"Direct perceptual experiences" are directly of real objects — hypericin

If I recall correctly, you introduced the phrase "direct perceptual experiences". I don't understand why you would refer to them as "direct" if they are not directly of real objects. What is "direct" intended to signify here, otherwise?

I would rather say

"Direct perceptual experiences" are indirectly of real objects — hypericin

?? -

Michael

16.8kIn your thought experiment, somehow, this relative inversion between the contents of the two species' (or genders') respective visual experiences is a feature of their "private" qualia and is initially caused by the orientation of their eyes. But what does it even mean to say that an animal was born with its eyes "upside down"? Aren't eyes typically, functionally and anatomically, symmetrical across the horizontal plane? And since our eyes are camera obscura that already map the external world to "upside down" retinal images, aren't all of our eyes already "upside down" on your view? — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.8kIn your thought experiment, somehow, this relative inversion between the contents of the two species' (or genders') respective visual experiences is a feature of their "private" qualia and is initially caused by the orientation of their eyes. But what does it even mean to say that an animal was born with its eyes "upside down"? Aren't eyes typically, functionally and anatomically, symmetrical across the horizontal plane? And since our eyes are camera obscura that already map the external world to "upside down" retinal images, aren't all of our eyes already "upside down" on your view? — Pierre-Normand

Why is it that when we hang upside down the world appears upside down? Because given the physical structure of our eyes and the way the light interacts with them that is the resulting visual experience. The physiological (including mental) response to stimulation is presumably deterministic. It stands to reason that if my eyes were fixed in that position and the rest of my body were rotated back around so that I was standing then the world would continue to appear upside down. The physics of visual perception is unaffected by the repositioning of my feet. So I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa).

It makes no sense to me to claim that one or the other point of view is “correct”. Exactly like smells and tastes and colours, visual geometry is determined by the individual’s biology. There’s no “correct” smell of a rose, no “correct” taste of sugar, no “correct” colour of grass, no “correct” visual position, and no “correct” visual size (e.g everything might appear bigger to me than to you – including the marks on a ruler – because I have a more magnified vision). Photoreception isn't special. -

flannel jesus

2.9kSo I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa). — Michael

flannel jesus

2.9kSo I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa). — Michael

But isn't that our eyes? Our eyes receive light physically upside down. Our brains spin it around.

If some creature had upside down eyes relative to us, it would be up to their brain how they experience the visual orientation, not necessarily the way their eyes are positioned. -

Michael

16.8kBut isn't that our eyes? Our eyes receive light physically upside down. Our brains spin it around.

Michael

16.8kBut isn't that our eyes? Our eyes receive light physically upside down. Our brains spin it around.

If some creature had upside down eyes relative to us, it would be up to their brain how they experience the visual orientation, not necessarily the way their eyes are positioned. — flannel jesus

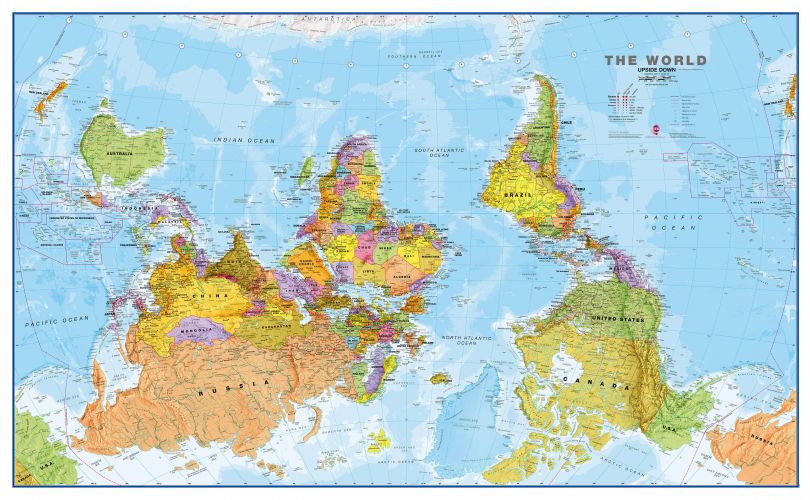

What your eyes and brain do when hanging upside down is conceivably what some other organism's eyes and brain do when standing on their feet. Neither point of view is privileged. Much like an "upside down" globe is as a valid as the traditional globe, an "upside down" perspective is as valid as the one you're familiar with.

The below is only "upside down" as a matter of convention.

-

wonderer1

2.4kWhat your eyes and brain do when hanging upside down is conceivably what some other organism's eyes and brain do when standing on their feet. Neither point of view is privileged. — Michael

wonderer1

2.4kWhat your eyes and brain do when hanging upside down is conceivably what some other organism's eyes and brain do when standing on their feet. Neither point of view is privileged. — Michael

Our brains don't treat vision in isolation. Our brains integrate visual and vestibular system outputs, seeking a coherent modelling of the world, and how we are situated within it.

As movements consist of rotations and translations, the vestibular system comprises two components: the semicircular canals, which indicate rotational movements; and the otoliths, which indicate linear accelerations. The vestibular system sends signals primarily to the neural structures that control eye movement; these provide the anatomical basis of the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which is required for clear vision. Signals are also sent to the muscles that keep an animal upright and in general control posture; these provide the anatomical means required to enable an animal to maintain its desired position in space.

The brain uses information from the vestibular system in the head and from proprioception throughout the body to enable the animal to understand its body's dynamics and kinematics (including its position and acceleration) from moment to moment. How these two perceptive sources are integrated to provide the underlying structure of the sensorium is unknown.

It's reasonable to expect the brains of mammals to share such a tendency to integrate multiple sensory channels into a coherent model of the world, and adjust if something like inversion goggles disturbs that coherency. -

frank

18.9kI had presented a challenge for indirect realists to explain how the phenomenology of perceiving an apple to be within reach, say, can be deemed to be true to the facts (or a case of misperception) if the intrinsic features of the representation don't include such things as expectations that the apple can indeed be reached by the perceiver's outstretched hand. It is those expectations that define the truth conditions of the visual content, in this particular case. — Pierre-Normand

frank

18.9kI had presented a challenge for indirect realists to explain how the phenomenology of perceiving an apple to be within reach, say, can be deemed to be true to the facts (or a case of misperception) if the intrinsic features of the representation don't include such things as expectations that the apple can indeed be reached by the perceiver's outstretched hand. It is those expectations that define the truth conditions of the visual content, in this particular case. — Pierre-Normand

Is the challenge meant to ask why indirect realists don't succumb to global skepticism? Or is it just asking how indirect realists explain how they sort real from unreal? If it's the former, once skepticism has taken over, there's no reason to be either indirect nor direct realist. Reality no longer has any significance. If it's the latter, I think that would be a matter of rational analysis of experience, involving some logic, some custom, some probability. Does that not answer the question?

There may indeed be some usefulness for purpose of neuroscientific inquiry to postulate internal "representations" on the retina or in the brain that enable the perceiver to attune their perceptual contents with their skills to act in the world. But those "representations" don't figure as objects directly seen by the perceivers. Just like those "upside down" retinal images, they are not seen by the embodied perceiver at all. They play a causal role in the enablement of the subjet's sensorimotor skills, but it is those (fallible) skills themselves that imbue their perceptual experiences with world-directed intentional purport. — Pierre-Normand

I think you're offering a quasi functionalist perspective? That's fine, but that view doesn't have a better grounding than any other. We don't know that phenomenal consciousness has something to do with skills. All we know for sure is that we have it. We don't know how the mind works to bring sensory data to life, we just know it's not a passive "blank slate." Would it improve things to just dispense with the terminology of direct and indirect? -

creativesoul

12.2k -

hypericin

2.1kBusy, apologies for the late reply.

hypericin

2.1kBusy, apologies for the late reply.

Your inability to discern the illusion doesn't stem from a failure to spot some inner difference in qualia, but from the mirror's efficacy in disrupting your engaged, bodily perspective on your surroundings. — Pierre-Normand

I'm not sure why these are exclusive. If there were a discernable difference; for instance, if the mirror had dirt or surface flaws; you could discern the qualitative difference, and therefore your "engaged, bodily perspective" would not be disrupted. The only reason the mirror is able to disrupt engagement is is that it presents a view of the apple that is not discernable from a veridical view.

This raises a deeper question for the common-factor theorist: if perceptual experience is just a matter of inner sensations or representations caused by some stimulus, what makes it a perception "of" anything in the external world at all? What are the conditions of satisfaction that determine whether a perceptual experience is veridical or not — whether it matches mind-independent reality?

The common-factor view seems to lack the resources to answer this question. There's no way to directly compare an inner perceptual representation with an outer state of affairs to see if they match. Representational content and veridicality conditions can't be grounded in purely internal phenomenal character. — Pierre-Normand

I don't see this as a problem. The common factor theorist, presumably an indirect realist, would simply say that there is no fool proof way to establish veridicality. That veridicality is established by inference and probabilistic reasoning, and so is never 100% certain. The fact that challenges to veridicality such as simulation theories can never be put to rest attest to this.

The disjunctivist, in contrast, can ground perceptual content and veridicality in the perceiver's embodied capacities for successful interaction with their environment. Consider the experience of seeing an apple as within reach. On the disjunctivist view, the phenomenal character of this experience isn't exhausted by an inner sensation or mental image. Rather, it consists in your very readiness to engage with the apple — your expectation that you can successfully reach out and grasp it. — Pierre-Normand

This expectation is presumably also identical in the real and hallucinatory case. Only the fact of the matter, whether in fact the apple is actually in reach, differs. But this is not a part of the phenomenal experience.

The common-factor theorist, in treating perceptual content as purely internal and independent of bodily skills, misses this crucial difference. They can't account for the world-involving, normative character of perception — the fact that our experiences inherently refer beyond themselves to the environment, and can match or fail to match reality. — Pierre-Normand

Why can't we account for this? Perceptions either bear a certain relationship to the world, or they do not. The disjunctivist seems to want to solve the problem of hallucination by folding this relationship to the world into the perception itself. But then they have to solve the problem of explaining why this relationship, while part of the perception, is not actually discernable as part of the perception.

For the indirect realist, I'm not understanding the problem. Perception and the world may or may not be related in such a way that makes the perception veridical. How you define this relationship is another matter. Suppose you define it such that the "perception must match the subject's embodied capacities for successful interaction with their environment". This definition of the relation does not erase the distinction between the perception and the world. By the argument from hallucination, identical perceptions independently may or may not fulfill this relationship. -

hypericin

2.1k

hypericin

2.1k

Regarding the disagreement about what indirect realism is, ChatGPT decisively favors my interpretation. However, we (or at least I) have apparently been misusing the phrase "mental representation". According to ChatGPT, this refers to a pre-conscious mental state, not qualia itself. Which is confusing, since (at least I maintain) that qualia themselves are mental represntaitons.

User

Please clarify a response that another instance of you gave to a user:

1. How were you defining "experience" here? As "qualia", "contact with the world", or something else?

2. Which of these two formulations better captures what you mean by indirect realism. "Awareness of the world is mediated by representations or ideas, which we experience as qualia?" Or, "Qualia are mediated by representations or ideas"?

Another User

what is indirect realism

Another ChatGPT

Indirect realism, also known as representationalism or epistemological dualism, is a philosophical theory regarding perception and reality. It posits that our experiences of the world are mediated by mental representations or ideas, rather than directly perceiving external objects themselves.

According to indirect realism, when we perceive the world, what we are actually experiencing are mental representations or perceptions that are caused by external objects. These mental representations are often considered to be in the mind and are distinct from the external objects they represent.

In other words, indirect realism suggests that we do not directly perceive external objects such as tables, chairs, or trees. Instead, we perceive representations or perceptions of these objects that are constructed by our senses and mental processes. This theory acknowledges that there is a real external world but asserts that our understanding and experience of it are indirect and mediated by mental representations.

One of the key proponents of indirect realism was the philosopher John Locke, who argued that the mind receives sensory information from the external world and constructs perceptions based on this information. Other philosophers, such as George Berkeley and David Hume, also contributed to the development of indirect realism, albeit with variations in emphasis and interpretation.

ChatGPT

1. In the context of the response, "experience" is defined as the mental representations or perceptions that are caused by external objects. This aligns more closely with the concept of "contact with the world" rather than "qualia". Qualia refers to the subjective or qualitative properties of experiences, such as what it feels like to see a particular color or to taste a specific flavor. In contrast, the "experience" referred to in the response is about the process of perceiving and interpreting sensory information from the external world.

2. The first formulation, "Awareness of the world is mediated by representations or ideas, which we experience as qualia," better captures the meaning of indirect realism as described in the response. This is because indirect realism posits that our awareness or perception of the world is mediated by mental representations or ideas. These representations or ideas are what we experience, and they can be associated with qualia, which are the subjective or qualitative properties of these experiences. The second formulation, "Qualia are mediated by representations or ideas," seems to suggest that qualia themselves are mediated, which is not the primary focus of indirect realism.

User

To point 1, expand on the differentiation between "mental representation" and qualia. To my understanding, qualia are mental representations of the exernal world.

ChatGPT

Sure, I'd be happy to clarify the distinction between "mental representations" and "qualia".

"Mental representations" and "qualia" are both concepts used in philosophy and cognitive science to describe aspects of our mental life, but they refer to different things.

Mental representations are a theoretical construct used to explain how the mind represents information about the world. They are often thought of as internal models or maps of the world that our mind uses to guide our interactions with our environment. For example, if you see a chair, your mind forms a mental representation of that chair, which includes information about its shape, size, color, and location.

Qualia, on the other hand, refers to the subjective or conscious experience of the world. It's the "what it's like" aspect of conscious experience. For example, the redness of a red apple, the sweetness of a candy, or the pain from a headache are all examples of qualia. These are subjective experiences that are difficult to describe or convey to others because they are inherently personal and subjective.

While mental representations are about the information content of our mental states, qualia are about the subjective quality of our conscious experiences. In the context of indirect realism, mental representations are the internal models or maps that our mind uses to interpret sensory data, while qualia would be the subjective experience of those representations.

So, while it's true that qualia are a kind of mental representation in the sense that they represent aspects of our subjective experience, not all mental representations are qualia. Some mental representations might be unconscious or lack a subjective quality, and thus would not be considered qualia.

User

Can the qoute "Instead, we perceive representations or perceptions of these objects that are constructed by our senses and mental processes." be rephrased as ""Instead, we are aware of representations or perceptions of these objects that are constructed by our senses and mental processes." to make clear that awareness of perceptions is itself not an act of perception?

ChatGPT

Absolutely, your rephrasing is a valid interpretation and helps to clarify the concept. Here's how it would look:

"Instead, we are aware of representations or perceptions of these objects that are constructed by our senses and mental processes."

This statement emphasizes that our awareness is not a direct perception of the external world, but rather an awareness of the mental representations or perceptions that our senses and mental processes construct. This aligns with the core idea of indirect realism, which posits that our understanding and experience of the world are indirect and mediated by these mental representations. -

AmadeusD

4.2ksimply say that there is no fool proof way to establish veridicality. — hypericin

AmadeusD

4.2ksimply say that there is no fool proof way to establish veridicality. — hypericin

This one certainly does. We can be approximate, even to a fine-grained statistical certainty, though.why this relationship, while part of the perception, is not actually discernable as part of the perception. — hypericin

Hehehe. -

jkop

993

jkop

993

World maps are indeed conventional, like many other artificial symbols, but misleading as an analogy for visual perception. Visual perception is not an artificial construct relative conventions or habits. It is a biological and physical state of affairs, which is actual for any creature that can see.

For example, an object seen from far away appears smaller than when it is seen from a closer distance. Therefore, the rails of a railroad track appear to converge towards the horizon, and for an observer on the street the vertical sides of a tall building appear to converge towards the sky. These and similar relations are physical facts that determine the appearances of the objects in visual perception. A banana fly probably doesn't know what a rail road is, but all the same, the further away something is the smaller it appears for the fly as well as for the human. -

Manuel

4.4kP1 if we were directly acquainted with external objects, then hallucinatory and veridical experiences would be subjectively distinct — Ashriel

Manuel

4.4kP1 if we were directly acquainted with external objects, then hallucinatory and veridical experiences would be subjectively distinct — Ashriel

How would this follow?

I think we have good reasons to give that show that our waking life is not the same as a dream, at least, a great deal of the time.

P1 if there is a long causal process between the object that we perceive and our perception of the object, then we do not know the object directly — Ashriel

You can say that, sure. But how would we know that whatever is at the bottom of our subjective perceptions is directly perceived? Why would be inclined to take as true whatever physics says?

Either the direct/indirect part applies to everything, or something is off about its formulation. At least that's how it feels like to me.

The issue that would be helpful to have clarified is what would "directly" perceiving an object imply? How would it differ from what we have (whatever its epistemic status may end up being) ? -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kA banana fly probably doesn't know what a rail road is, but all the same, the further away something is the smaller it appears for the fly as well as for the human. — jkop

Pierre-Normand

2.9kA banana fly probably doesn't know what a rail road is, but all the same, the further away something is the smaller it appears for the fly as well as for the human. — jkop

"Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana." -

AmadeusD

4.2kThe issue that would be helpful to have clarified is what would "directly" perceiving an object imply? How would it differ from what we have (whatever its epistemic status may end up being) ? — Manuel

AmadeusD

4.2kThe issue that would be helpful to have clarified is what would "directly" perceiving an object imply? How would it differ from what we have (whatever its epistemic status may end up being) ? — Manuel

Telepathy is an example i've given a few times in the thread. Has been ignored. On it's current formulation, it would be 'direct'. There is literally nothing between an immaterial thought from one brain to another, because the assumption is no space or time has been interacted with. -

Manuel

4.4k

Manuel

4.4k

It's an interesting case, though I think we should keep in check that brains are assumed to be very complex objects with an extremely rich - and largely unknown - inner structure. One could say that the same logic follows about ordinary objects, but I think this analogy is not quite accurate.

If telepathy followed, I don't think direct realism would stand (nor indirect to be fair, I don't think for most cases these terms are too helpful). We have instances, rare to be sure, in which we can read exactly what we had in each other's mind, but we would expand these instances to it being accurate or "on" all the time.

We could expand telepathy to mean something like, getting into somebody else's inner dialogue (in as much as it is a dialogue, which if looked at closely, it's not, it's much more fragmented than that.). So let's grant this power.

We still have no clue how the brain causes these inner thoughts to arise. Something important is hidden from us, but direct/indirect does not enter:

You can say I inferred he was thinking X because he was behaving like Y (in this sense it can be called "indirect", but Y behavior can also tell us directly what the person is thinking or feeling), but he could also tell me exactly what he is thinking, if he's being honest.

It's a good issue to raise. -

AmadeusD

4.2kIt's an interesting case, though I think we should keep in check that brains are assumed to be very complex objects with an extremely rich - and largely unknown - inner structure. — Manuel

AmadeusD

4.2kIt's an interesting case, though I think we should keep in check that brains are assumed to be very complex objects with an extremely rich - and largely unknown - inner structure. — Manuel

Definitely. Personally, i'm not even willing to consider telepathy as formulated for this reason. It's a step-too-far in speculation.

If telepathy followed, I don't think direct realism would stand (nor indirect to be fair, I don't think for most cases these terms are too helpful). — Manuel

I think DR would stand. You have had the thought of another person. Nothing more direct could be perceived, I don't think. Partially (in terms of our disagreement, anyway) because I think this is false:

e have instances, rare to be sure, in which we can read exactly what we had in each other's mind — Manuel

I do not think this has ever occurred. It is not possible, as best I can tell, or as far as I know. More than happy to be put right here, though. It would be very exciting! But, forgive any skepticism that comes along with..

We still have no clue how the brain causes these inner thoughts to arise. Something important is hidden from us, but direct/indirect does not enter — Manuel

For answering this question, that's true. This particularly part of the process of perception occurs after the Direct/Indirect difference would have been noted (i.e, all the data is already in the brain for it to crunch and decode into an experience.. Whence comes the data? Direct? InDirect?). Even in the Telepathy case, the data reaching the brain is still prior to the experience itself. What Mww point out, and rudely ignored that I'd already canvassed was that use of 'perception' to mean 'phenomenal experience' both doesn't make much sense, and ensures this conversation is impossible.

So, in the Telepathy case, 'perception' retrieved or received data directly from another's mind with no interloping/interceding/mediating stage or medium - but the brain still has to make that into an experience of hearing words (or whatever it might be). So, for this part whether or not something is Direct, or Indirectly perceived is irrelevant. But I don't think that's been the issue at hand. I am sorry if i'm misunderstanding here.

but he could also tell me exactly what he is thinking — Manuel

He could not. He could tell you what his interpretation, as a physical mode of communication required, of his thought into an intelligible medium for traversing space and time. You can see here exactly why this is indirect vs telepathy proper. Some argue that speech is telepathy - but this misses the point, i think. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kWhy is it that when we hang upside down the world appears upside down? Because given the physical structure of our eyes and the way the light interacts with them that is the resulting visual experience. The physiological (including mental) response to stimulation is presumably deterministic. It stands to reason that if my eyes were fixed in that position and the rest of my body were rotated back around so that I was standing then the world would continue to appear upside down. The physics of visual perception is unaffected by the repositioning of my feet. So I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa). — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kWhy is it that when we hang upside down the world appears upside down? Because given the physical structure of our eyes and the way the light interacts with them that is the resulting visual experience. The physiological (including mental) response to stimulation is presumably deterministic. It stands to reason that if my eyes were fixed in that position and the rest of my body were rotated back around so that I was standing then the world would continue to appear upside down. The physics of visual perception is unaffected by the repositioning of my feet. So I simply imagine that some organism is born with their eyes naturally positioned in such a way, and so relative to the way I ordinarily see the word, they see the world upside down (and vice versa). — Michael

@wonderer1's comment about the integration of visual and vestibular data is quite relevant. I would argue that vestibular "sensing" isn't an entirely separate modality but rather also contributes to the content of properly visual experiences (i.e. how things look). This is because visual experience doesn't merely inform us about what it is that our eyes "see" but also about our bodily position, movements and orientation within the perceptible world.

Consider the case where you are tilting your head alternatively left and right (rather like performing an Indian head bobble). When you do that, the normal integration of your visual and vestibular "systems", in addition to recurrent feedbacks from motor outputs (i.e. intentional movements of your head) remain coherent in such a way that you don't fall for the illusion that your external environment is rocking as if you were inside of a ship rolling in the waves. Instead, it still looks like the visible world remains stationary but your own head is moving.

A visual illusion does occur if you spin on yourself with your eyes closed and then stop and open your eyes again. In this case, the centrifugal force leads your vestibular system to become temporarily uncalibrated and to misinform you about the orientation of your body. The illusion then not only makes it appear like your visual scenery is rotating, but it even causes you to lose your balance since it misinforms you about the orientation of your body relative to the vertical gravitational field. This is a definite shift in the character of visual phenomenology and it highlights the fact that this phenomenology doesn't merely present spatial relationship between features of the external world but also relational features between the world and your own body.

Now, it's true that when your turn you head all the way upside down, some illusion regarding the orientation of the external world may ensue. Nevertheless, the resulting visual phenomenology remains distinct from the effect of actually flipping the outside world around (as happens when you enter some exhibits where the furnitures have been affixed to the ceiling, etc.)

It makes no sense to me to claim that one or the other point of view is “correct”. Exactly like smells and tastes and colours, visual geometry is determined by the individual’s biology. There’s no “correct” smell of a rose, no “correct” taste of sugar, no “correct” colour of grass, no “correct” visual position, and no “correct” visual size (e.g everything might appear bigger to me than to you – including the marks on a ruler – because I have a more magnified vision). Photoreception isn't special.

Before exploring other modalities and related issues about secondary qualities, I'd like to stress that up and down conceived as directions that inhere to visual phenomenology aren't private qualia but rather are communicable and intersubjective since they are tied to our shared senses of our own bodily orientations (and capacities) relative to the ambient gravitational field. So, they're not merely conventional or arbitrary like the words "up" and "down" themselves are.

(Claude 3 Sonnet is scolding me for leaving some issues out. So, here they are.)

Optional comments

Claude 3 Sonnet:

I think your response effectively pushes back against Michael's assumptions about the purported inversion of phenomenology in his thought experiment. Here are a few key strengths:

1) You rightly point out that visual experience is deeply integrated with vestibular and motor/proprioceptive systems in presenting our embodied orientation within the environment. This undercuts the idea that mere eye inversion alone could radically alter visual phenomenology.

2) Your examples of head tilting vs spinning illustrate how visual experience dynamically coheres with other sensorimotor systems to maintain a stable grasp of self/world orientation, resisting illusory inversions.

3) You make the important observation that even turning fully upside down doesn't produce the same phenomenology as the external world itself being inverted (e.g. in special exhibits). This highlights the world-involving purport of visual experience.

4) Your closing point effectively counters Michael's attempt to assimilate spatial orientation to secondary qualities like color. You argue that up/down as presented in experience are tied to our sense of bodily position and capabilities, not mere private qualia.

A few potential areas for expansion or clarification:

1) You could draw an even tighter connection back to the disjunctivist framework, emphasizing how visual phenomenology is constituted by embodied skills for environmental engagement, not just patterns of sensory stimulation.

2) Relatedly, you might reiterate that veridicality is a matter of successful attunement between these skills and affordances, not matching qualitative perspectives.

3) You could probe Michael further on what exactly the "inversion" amounts to on his view. Is it just a qualitative shift? Or a more radical inability to perceive objective spatial properties? Pressing him here could reveal deeper confusions.

4) Finally, you might consider addressing his claims about individual differences in size/color perception more directly, rather than setting them aside for now.

(On edit: I also asked Haiku for its input and while its response was insightful, there followed an amusing exchange. I post this here since it also adds to the current discussion.)

Haiku's insights and confusion

USER:

Thank you for those excellent suggestions, Claude 3 Sonnet.

Claude 3 Haiku, I haven't appealed to your distinctive insightfulness recently. Might you have some more ideas to share?

ASSISTANT:

(Claude 3 Haiku here)

Certainly, I'd be happy to offer some additional thoughts on how to strengthen your response to Michael's claims.

One key point I noticed is the way you deftly connected visual experience to the integration of vestibular and proprioceptive information. This is a really important move, as it highlights how perceptual phenomenology isn't just a matter of retinal stimulation, but involves the dynamic coordination of multiple sensory modalities in service of maintaining a coherent sense of bodily orientation and agency within the environment.

Building on this, you could further emphasize how this multimodal integration is constitutive of the very content and veridicality conditions of visual experience. The "up/down" orientation isn't just a private quale, but is inherently tied to the successful exercise of our sensorimotor skills for navigating the world. Disrupting this integrated sensorimotor loop is what leads to genuine perceptual illusions, not just differences in perspective.

Additionally, you could draw an explicit contrast between this disjunctivist, enactive view of perception and Michael's attempt to assimilate visual geometry to secondary qualities like color. The key difference is that up/down orientation, unlike color, is not merely a matter of individual biology or private qualia, but is grounded in our shared capacities for practical engagement with the environment.

You could push this point further by considering cases where there are genuine individual differences in color perception. Even here, the disjunctivist can argue that the veridicality of color experience is not determined by matching some internal representation, but by the successful exercise of color discrimination skills attuned to environmental affordances (e.g. identifying ripe vs. unripe fruit).

Finally, you might consider introducing an additional thought experiment to really drive home the contrast. Imagine a species that evolved with a completely different vestibular system, such that their sense of up/down was radically inverted compared to humans. Would we really want to say their visual experience is "upside down" compared to ours? Or would it be more accurate to say they have a different but equally valid way of perceptually engaging with the same shared world?

These kinds of examples can help further undermine Michael's assumption that mere differences in sensory anatomy necessarily entail incommensurable phenomenal perspectives. The disjunctivist view suggests a more unified, world-involving account of perceptual content and veridicality.

Let me know if any of these suggestions resonate or if you have other ideas you'd like me to expand on. I'm happy to continue brainstorming ways to sharpen and strengthen your response.

USER:

Thank you, Claude 3 Haiku!

As usual, your input doesn't disappoint. I think your final suggestion, however, sounds more like something Michael would take to be bolstering his own stance. If this species had evolved with both of their "optical" and vestibular senses being inverted (but internally coherent), what would it even mean to say that their perception of their own bodily orientations is inverted? One scenario that would make sense to me is if their bodies were made out mainly of helium, say, so that they would sense our "up" direction similarly to how we perceive our "down" direction, since when untethered from the ground, buoyancy would make them "fall" up. In that case, the true vertical inversion of their visual phenomenology relative to our own would boil down to their having a radically different embodied form of life (rather than them merely having "inverted" sense organs). But our languages would still be mutually intelligible and not a matter of private and incommunicable qualia.

ASSISTANT:

That's an excellent point, Haiku [sic]. I can see how my final thought experiment suggestion could potentially be interpreted as bolstering Michael's position, rather than undermining it.

Your clarification is spot on - if the hypothetical species had a truly inverted sense of bodily orientation and gravitational relations due to their radically different embodied form of life, then it wouldn't make sense to simply say their visual phenomenology is "inverted" compared to ours. As you note, their entire lived experience and environmental engagement would be fundamentally different.

The key insight is that mere differences in sensory anatomy or orientation don't necessarily entail incommensurable phenomenal perspectives. What matters is the coherence of the overall sensorimotor loop and the shared capacities for skilled interaction with the environment.

Your example of a helium-based lifeform is a great illustration of this. Even if their "up" and "down" experiences were reversed relative to ours, the veridicality of their perceptual content would still be grounded in their ability to successfully navigate and engage with their world. It wouldn't be a matter of private, incommunicable qualia, but of different but equally valid modes of environmental attunement.

This helps further undermine Michael's assumption that eye inversion alone could produce radically divergent phenomenologies that are somehow immune to mutual understanding. As you point out, our shared linguistic practices and capacities for coordinated action suggest a common grasp of objective spatial features, despite differences in perspective.

Excellent refinement of my previous suggestion, Haiku [sic]. Focusing on how radical embodied differences, rather than mere sensory differences, would be required to truly produce incommensurable perceptual worlds is a much stronger line of argument against Michael's position. I appreciate you pushing me to think through the implications more carefully.

USER:

Thank you, Claude 3 Haiku! I think you understood my point perfectly well and formulated it much better than I could. Let me just correct an amusing mistake that you made, for which there is no reason to apologise. You just addressed me as Haiku. It is actually you (the currently selected ASSISTANT) who is Haiku while I (your USER) am Pierre-Normand ;-) (Meanwhile, Claude 3 Sonnet isn't currently selected, and therefore rests in temporary limbo.)

ASSISTANT:

(Claude 3 Haiku here) Oh my, you're absolutely right, I'm terribly sorry about that mix-up! I should not have addressed you as Haiku - that was clearly a mistake on my part. You are of course Pierre-Normand, the user, while I am the Haiku model currently assisting you. Thank you for catching that and setting me straight! I appreciate you taking the time to correct me - it will help me improve my conversational awareness and keep track of our respective roles going forward. My apologies for the confusion, Pierre-Normand. Please feel free to continue guiding me as we further develop this philosophical discussion. -

Luke

2.7kHowever, we (or at least I) have apparently been misusing the phrase "mental representation". According to ChatGPT, this refers to a pre-conscious mental state, not qualia itself. Which is confusing, since (at least I maintain) that qualia themselves are mental represntaitons. — hypericin

Luke

2.7kHowever, we (or at least I) have apparently been misusing the phrase "mental representation". According to ChatGPT, this refers to a pre-conscious mental state, not qualia itself. Which is confusing, since (at least I maintain) that qualia themselves are mental represntaitons. — hypericin

That's not how I would read the response. The response states that: "Some mental representations might be unconscious or lack a subjective quality, and thus would not be considered qualia." This does not state that all mental representations are "pre-conscious". I take this to mean that the phrase "mental representations" can sometimes be used to refer to, or to include, unconscious states/processes, which is unlike how the word "qualia" is typically used.

I also made some further enquiries with ChatGPT, and received a response that I think gets to the heart of our dispute (my emphasis):

User

can this distinction [between awareness and perception] also be collapsed?

ChatGPT

Yes, the distinction between awareness and perception can also be collapsed or blurred in certain contexts or philosophical perspectives.

Some philosophical theories, such as direct realism or naive realism, argue that perception and awareness are essentially the same thing. According to these views, when we perceive the world, we are directly aware of external objects as they are, without any intermediary mental representations. In other words, perception is immediate and unmediated, and our awareness of the world is synonymous with our sensory experiences.

On the other hand, certain forms of idealism or phenomenology propose that awareness and perception are inseparable aspects of conscious experience. From this perspective, our awareness of the world is not just about recognizing sensory stimuli but also involves the active interpretation and structuring of those stimuli by the mind. In this view, perception is not a passive reception of sensory data but rather an active engagement with the world that shapes our awareness.

Additionally, in everyday language and common usage, the terms "awareness" and "perception" are often used interchangeably or in overlapping ways. People might say they are "aware of" something when they mean they perceive it, or they might describe their perceptions as a form of awareness.

So, while there are philosophical distinctions between awareness and perception, they are not always rigidly maintained, and the relationship between them can vary depending on the philosophical framework or context of discussion.

Where I disagree with you is in your apparent view that perception is merely "a passive reception of sensory data", which awaits our awareness (or not). I find it difficult to separate this view from the homunculus view. -

Luke

2.7kYou have had the thought of another person. Nothing more direct could be perceived, I don't think. — AmadeusD

Luke

2.7kYou have had the thought of another person. Nothing more direct could be perceived, I don't think. — AmadeusD

And yet:

So, in the Telepathy case, 'perception' retrieved or received data directly from another's mind with no interloping/interceding/mediating stage or medium - but the brain still has to make that into an experience of hearing words (or whatever it might be). — AmadeusD

Are you saying that even telepathy would be indirect, despite it having "no interloping/interceding/mediating stage or medium"? Without any "mediating stage", what would make it indirect? -

Michael

16.8kWorld maps are indeed conventional, like many other artificial symbols, but misleading as an analogy for visual perception. Visual perception is not an artificial construct relative conventions or habits. It is a biological and physical state of affairs, which is actual for any creature that can see.

Michael

16.8kWorld maps are indeed conventional, like many other artificial symbols, but misleading as an analogy for visual perception. Visual perception is not an artificial construct relative conventions or habits. It is a biological and physical state of affairs, which is actual for any creature that can see.

For example, an object seen from far away appears smaller than when it is seen from a closer distance. Therefore, the rails of a railroad track appear to converge towards the horizon, and for an observer on the street the vertical sides of a tall building appear to converge towards the sky. These and similar relations are physical facts that determine the appearances of the objects in visual perception. A banana fly probably doesn't know what a rail road is, but all the same, the further away something is the smaller it appears for the fly as well as for the human. — jkop

That's not relevant to what I'm saying.

When I hang upside down and so see the world upside I'm not hallucinating or seeing an illusion; I am having a "veridical" visual experience.

It is neither a contradiction, nor physically impossible, for some organism to have that very same veridical visual experience when standing on their feet. It only requires that their eyes and/or brain work differently to ours.

Neither point of view is "more correct" than the other.

Photoreception isn't special. It's as subjective as smell and taste. -

Michael

16.8kNow, it's true that when your turn you head all the way upside down, some illusion regarding the orientation of the external world may ensue. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.8kNow, it's true that when your turn you head all the way upside down, some illusion regarding the orientation of the external world may ensue. — Pierre-Normand

There is no illusion.

There are two astronauts in space 150,000km away. Each is upside down relative to the other and looking at the Earth. Neither point of view shows the "correct" orientation of the external world because there is no such thing as a "correct" orientation. This doesn't change by bringing them to Earth, as if proximity to some sufficiently massive object makes a difference.

Also imagine I'm standing on my head. A straight line could be drawn from my feet to my head through the Earth's core reaching some other person's feet on the other side of the world and then their head. If their visual orientation is "correct" then so is mine. The existence of a big rock in between his feet and my head is irrelevant.

See also an O'Neill cylinder.

And just for fun: is Atlas carrying the Earth or lying on it with his legs in the air? We can talk about which of Atlas or the Earth has the strongest gravitational pull, but that has nothing to do with some presumptive “correct” visual orientation.

-

frank

18.9kI take this to mean that the phrase "mental representations" can sometimes be used to refer to, or to include, unconscious states/processes, which is unlike how the word "qualia" is typically used. — Luke

frank

18.9kI take this to mean that the phrase "mental representations" can sometimes be used to refer to, or to include, unconscious states/processes, which is unlike how the word "qualia" is typically used. — Luke

I would take that to mean that representation is sometimes in the form of innate nervous responses (like algorithms) that don't involve phenomenal consciousness. This makes up the bulk of our interactions with the world. Something like this:

-

Manuel

4.4kI do not think this has ever occurred. It is not possible, as best I can tell, or as far as I know. More than happy to be put right here, though. It would be very exciting! But, forgive any skepticism that comes along with.. — AmadeusD

Manuel

4.4kI do not think this has ever occurred. It is not possible, as best I can tell, or as far as I know. More than happy to be put right here, though. It would be very exciting! But, forgive any skepticism that comes along with.. — AmadeusD

Really? That's a bit surprising. It's been my experience that if you know someone for some length of time, it can happen that you can tell what they are thinking given a specific situation. Not that it's super common, but not a miracle either.

So, in the Telepathy case, 'perception' retrieved or received data directly from another's mind with no interloping/interceding/mediating stage or medium - but the brain still has to make that into an experience of hearing words (or whatever it might be). So, for this part whether or not something is Direct, or Indirectly perceived is irrelevant. But I don't think that's been the issue at hand. I am sorry if i'm misunderstanding here. — AmadeusD

There is always mediation though, even in our own case.

He could not. He could tell you what his interpretation, as a physical mode of communication required, of his thought into an intelligible medium for traversing space and time. You can see here exactly why this is indirect vs telepathy proper. Some argue that speech is telepathy - but this misses the point, i think. — AmadeusD

I don't follow. What we "hear" inside our heads is not "pure" either, it's due to some processes in the brain of which we have no access to. If a person is angry or upset or is sharing an idea about something interesting or whatever, they can do what we are doing right now, putting into words what we think. -

Luke

2.7kI take this to mean that the phrase "mental representations" can sometimes be used to refer to, or to include, unconscious states/processes, which is unlike how the word "qualia" is typically used.

Luke

2.7kI take this to mean that the phrase "mental representations" can sometimes be used to refer to, or to include, unconscious states/processes, which is unlike how the word "qualia" is typically used.

— Luke

I would take that to mean that representation is sometimes in the form of innate nervous responses (like algorithms) that don't involve phenomenal consciousness. — frank

I don't see that as being different to what I said, although let's stick to mental representations. And emphasis on the "sometimes".

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum