Comments

-

The Phenomenological Origins of MaterialismInteresting and thoughtful OP. :up:

Hence, the common sensibles of size, shape, quantity, etc. get considered "most real." We can see this in Galileo, Locke, etc. with the demotion of color to a "less real" (merely mental) "secondary quality," while shape and motion, etc. remain fully real "primary quantities." — Count Timothy von Icarus

We can also see how some people strive to remove the echo of the senses from this way of thinking, to make mathematics more abstract and thus, presumably, "more objective." For instance, LeGrange's 18th century mechanics textbook proudly announces that it uses no diagrams or drawings, only formulae. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Apparently there are two modern emphases you are bringing out. One is an emphasis on common sensibles, and the other is an emphasis on mathematics and mathematicization. What's curious is that they seem opposed. The first tends towards materialism and the second tends towards Platonism, and yet both flow in a special way out of the modern period.

I am not sure how to reconcile those two strands. If they are left unreconciled then the modern period appears schizophrenic, torn between an emphasis on common sensibles and an incompatible emphasis on mathematicization. Is there a ready way to reconcile the two? To reconcile thesis 1 and thesis 2? Or am I incorrect in thinking that they are opposed? -

What is real? How do we know what is real?- Crap, I was hoping you would be preoccupied with your essay contest. :razz:

Further, we don't begin with a solid foundation and build outwards. Rather I'd use the plant metaphor that we begin with a seed which, when nurtured in the proper environment, slowly takes roots to the soil and becomes something solid. — Moliere

But how is a seed not a solid foundation? That seems to be precisely what a seed is. From an edit:

It's as if Aristotle gives a theory of seed germination and growth, and in response you say, "I think you just have to throw seeds and see what happens." — Leontiskos

So rather than beginning with the certain I'd say we make random guesses and hope to be able to make it cohere in the long run. — Moliere

Aristotle is well aware that most people have no method, and just throw seeds randomly, hoping to stumble upon something or another. He just doesn't think such a person will produce reliable fruit.

I'd say it's on par with "From the more certain to the less certain" — Moliere

It's just a part of Aristotle's account in the Posterior Analytics. I use it because it is so uncontroversial.

I don't think that follows at all. I think that what this says is that Leontiskos can't understand how someone could think that sensibility and intelligibility are important unless they are not skeptics, rather than that one doesn't begin with skepticism. — Moliere

It follows as long as you understand what skepticism is. If one holds and presupposes that reality is intelligible, then they are not skeptical of that proposition. If they say, "Oh, well I am skeptical of X even though I believe and presuppose it entirely," then they are equivocating on the word 'skepticism'. This is but one example of moving from the more certain to the less certain. The "more certain" is that reality is intelligible. You are again captive to Aristotle's knowledge even without realizing it.

At the time one could reasonably, though falsely, believe they had reviewed "all the sciences" such that they could reasonably make inferences about "all of reality at its most fundamental". — Moliere

Not sure why you think someone has to review every scientific paper, for example. Seems an odd idea.

Aristotle, though he did not have access to all science, could feel confident that he'd responded to all the worthwhile arguments so that he could link science to metaphysics.

The sheer volume of knowledge today makes it so that Aristotle's procedure can't be carried out. So one's metaphysical realism can't be on the basis of science insofar that we are taking on a neo-Aristotelian framework -- it's simply impossible to do what Aristotle did today with how much there is to know. — Moliere

Okay, so this is the new argument, <If we do not read and survey every scientific claim, then we cannot be metaphysical realists (or else we can't connect science to metaphysics)>. Again, pretty clearly invalid. Or else, I am still in no way sure how you are getting from the premise to the conclusion. Why must a metaphysical realist read and review every scientific claim?

I'd start with Popper, at least, so falsification follows the form of a modus ponens. — Moliere

I'm not sure what it means to say that falsification follows the form of a modus ponens. Does Popper say this somewhere?

But then I'd say that in order to falsify something you have to demonstrate that it is false to such a degree that someone else will agree with you. — Moliere

Anyone at all?

Furthermore I don't think that for falsification to take place that the next theory which takes its place will be true or even needs to be demonstrated as true. — Moliere

So X can falsify Y even when X is not true?

I would say that there is truth and falsity, and then there are also beliefs about propositions, namely that they are true or false. Falsification can be viewed from either angle, but both are interconnected.

I think TPF probably needs a thread addressing the deep problems with an intersubjective approach to truth, given how many people here are captive to it. We can falsify an individual's belief, but only if the content of that belief itself has a truth value (apart from any particular individual). -

What is real? How do we know what is real?The purpose of using names isn't to demonstrate what I've read and understood, but to refer to a shared body of knowledge between speakers. So when I say "Aristotle", I presume you understand Aristotle well enough and modern science well enough to be able to put together the dots that teleology and modern science, especially of the enlightenment era, are in conflict.

I switched to divisibility because the example is as good as the teleological one -- namely, I don't know if Lavosier, on a personal level, might have believed there was some kind of teleology behind water, but the whole enlightenment project basically rejects teleology in favor of efficient causation for its mode of explanation -- this is one of the primary reasons people reject Enlightenment era materialism and go in various ways. — Moliere

So again, Aristotle's teleology does not contradict Lavoisier's chemical claim, whereas the idea that water is indivisible does contradict that chemical claim. So one argument is valid and the other is not. It is helpful that you switched over to a valid argument and left the invalid argument behind.

There is nothing about Lavoisier's claim that commits him to an anti-teleological view. The idea that Lavoisier lived in an age that often rejected teleology is not a real argument in favor of the idea that Lavoisier's chemical formula contradicts Aristotle's teleology, much less that the current state of affairs accepts the idea that one entails the other.

I think all it takes to grow in knowledge is to plant seeds and see what happens. — Moliere

I think that is so vague as to be saying nothing at all, and in this it causes many problems. I don't think you are even presenting a theory of knowledge growth here. It's as if Aristotle gives a theory of seed germination and growth, and in response you say, "I think you just have to throw seeds and see what happens."

But noting here: even our notions of "falsification" are at odds. So perhaps we cannot appeal to falsification in our back-and-forth, because even this is being equivocated in our dialogue. — Moliere

Well I know exactly what I mean by falsification. Do you know what you mean? Or is it a vague term that allows one to affirm all sorts of things, depending on what they prefer?

To say what's at stake: I don't think science delineates what is real. I also think that the project towards finding essences using the sciences is doomed to fail -- the big difference between Aristotle's and our day is the sheer amount of knowledge that there is. In Aristotle's day it probably seemed like a reasonable project to begin with the sciences and slowly climb up to a great metaphysical picture of the whole.

But any one scientist today simply can't have that perspective. Looking at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ their tagline on the front page states "PubMed® comprises more than 38 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books."

Aristotle could review all the literature that was in his day and respond to all his critics and lay out a potential whole. But he didn't have so many millions of papers or forebears to deal with. And I'd be more apt to look to the Gutenberg Press to explain this difference.

But this is only if we treat metaphysics as exactly the same as science, too. That was Aristotle's goal, but it need not be metaphysics goal. I'm more inclined to think that these metaphysical ways of thinking are ways of dealing with the sheer amount, the multiplicity, that one must consider to make a universal generalization. The generalizations, rather than capturing a higher truth, is a way of organizing the chaos for ourselves. — Moliere

Well, is there an argument here? And is it valid? The basis of any such argument is something like <There are more scientists and scientific papers today; therefore metaphysical realism cannot be true>. But as with many of your posts, I have no idea how you got from your premise to your conclusion. It seems pretty clear to me that scientists today are trying to understand the world, just as Aristotle was trying to understand the world. Both reject the idea that truths about reality could contradict one another, and therefore both seem to have a unified idea of science. I'm not sure how more scientists and more scientific papers in any way invalidates these propositions.

It is odd to say that it is false. If it is "good enough" to begin understanding, then it simply cannot be wholly false. If it is wholly false then it is not good enough to begin understanding. — Leontiskos

Another terminological difference. I tend to think attributions of "not wholly false" or "not wholly true" can be reduced to a set of sentences in which the name is sometimes the predicate and sometimes not the predicate, — Moliere

That's fine. My point still holds.

So what I see is that skepticism, rather than security, is the basis of knowledge. Jumping out into the unknown and making guesses and trying to make sense of what we do not know is how new knowledge gets generated — Moliere

As above, I don't think this is a theory. Note too that if one thinks "guess and try to make sense" is a viable approach, then they already hold to the idea that reality is intelligible and sensible. They are not starting from skepticism.

I think your construal of AW and LW is such that they look like they agree more than they do not agree. — Moliere

Sure, and we could add in your new thesis about indivisibility to complicate the picture, but my general point will still hold.

Aristotle's concern is philosophical and scientific, and he lives in an era where his project is feasibly both philosophical and scientific. He has a much wider theory of water that conflicts with the enlightenment, mechanistic picture of H2O which Lavoisier is credited with determining. I think of hisLavoisier's work primarily as a scientist because his work as a scientist was in improving analytic methods, and it was due to his care towards precision that he was able to demonstrate to the wider scientific community the ratio of Hydrogen to Oxygen you get with electrolysis. So maybe there's some philosophical work of his I do not know, but I'd say this work fits squarely within the scientific column, even if we don't have strict definitions to delineate when is what. — Moliere

I'm not sure why Lavoisier's claim that water is composed of H2O should not be considered philosophical. In this Lavoisier is involved in a truth claim of metaphysical realism. Similarly, the modern rejection of teleology is a metaphysical truth claim. It's not like there is some clear separation between philosophy and science.

And, likewise, Kripke is making a point about whether essences can be made viable in the 20th century after they had been largely abandoned by contemporary philosophy (even if there are other traditions which keep them). So he's a philosopher, but if science turns out to be wrong about the whole H2O thing his points will still stand(EDIT:or fall) regardless. — Moliere

I don't think your last sentence is true, namely the inference. Kripke's work depends on scientific claims. He could adapt his claims to something like, "If water is H2O then water is necessarily H2O," but he apparently wants to say more than "if". More, he is presupposing that some such "scientific" relations are demonstrable and existent, even if the relation between water and H2O turns out to be false. If all such "scientific" relations turn out to be false then Kripke's points will not stand. -

What is faith

Yep. :up:

And note here that the whole crux is the coherence of intersubjective approaches to truth. Is something made true because lots of people believe it? Or do lots of people believe it because it is true? Or is truth something else entirely, such that something can be true even if lots of people do not believe it?

The intersubjective analysis is of course highly dependent on the sample. When and where the sample is taken will largely determine whether some proposition is intersubjectively held. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?When these assumptions lead to paradox, we get "skeptical solutions" that learn to live with paradox, but I'd be more inclined to challenge the premises that lead to paradox. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I would say that with @J the problem is much deeper than that. Note that when he spoke of “true sentences” J was just borrowing a word out of Banno’s mouth. Banno would probably be willing to argue for the thesis that truth is the property of sentences, but J would not.

Pared down, J’s philosophical vice is that he won’t argue for any thesis at all. He will only stand on the sidelines and watch others philosophize as he comments from afar. For example, the closest he will get to arguing for “Stance Voluntarism” is to cite a paper by Chakravartty and a paper by Pincock and then critique Pincock (who argues against stance voluntarism). The idea that J himself believes in stance voluntarism and therefore should offer arguments in its favor would not occur to him.

The skepticism about truth and falsity is part of it, and that has been duly noted, but perhaps deeper is the methodological approach where one is unwilling to take upon themselves the burden of an argument for some real and substantial conclusion. Strange as it may seem, you will not find anything in any of J’s threads or posts akin to, “I believe X is true and here are my arguments for it.” And it is extremely odd to constantly cast doubt and contradict others without ever offering a stance of your own.

There are many facets to this. One is that people who believe only in intersubjective agreement don’t know how real arguments work, given that “truth” is in that case only about persuasion and then a majority vote. Thus rhetoric and the casting of doubt become the highest intellectual feats. But for most people these various facets and symptoms can be remedied by a desire to offer arguments for their beliefs and to be transparent about those arguments.

If one has the desire to provide arguments for their beliefs then they will in time move beyond mere doubt-casting and rhetoric, and begin to learn the art of reason. They will try to give arguments for their beliefs, they will stumble, they will revise their approach and/or their beliefs, and they will improve. But the person who is not even trying to give arguments for their beliefs is in quite the pickle, in that they deprive themselves of not only success, but also failure and improvement. Perhaps they even come to convince themselves that they have no beliefs at all, and neither should anyone else. Misology is the danger here, and in a surprisingly developed form. The remedy is to look at the discussion, recognize the beliefs one holds which are at stake in that discussion, and then to be willing to offer reasons and arguments in favor of those beliefs. To engage in discussions without possessing that willingness is deeply problematic. -

Beyond the PaleThis flows back to whether or not you require every mental action to be a judgement. — AmadeusD

I require every judgment to be a judgment, and I gave my definition of judgment <here> by following the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Nowhere in that definition is the claim that every mental act counts as a judgment. I noted that you are free to offer a different definition of judgment.

I do not - so, on my view this is a recognition only. I have simply taken what I've been told "We're here!" and run with it. I've not assessed it in any way (other than to pick up which words were aimed at me... is that hte judgement you mean? That's what Im calling recognition, to be clear). — AmadeusD

I think we're circling back to this and the conversation that followed:

I think assessing against a rubric requires judgment. If you need a 10-foot pipe and you examine two possible candidates, you are inevitably involved in judgments, no? — Leontiskos

You can say, "Oh, I only recognized that the first pipe was 10 feet long and the second was not," but in no way does this fail to count as a judgment given the definition I have laid out. The same holds with, "Recognizing that I have arrived at my destination." How did you recognize that if not by judging that the Google Maps voice told you that you arrived?

If you think recognizing that X is true involves no judgment, then you are denying the Oxford definition I have provided. Do you have an alternative definition?

This is analogous: I judged my condition, the surgeon and medical advice, and the prognosis to go under the knife (or, anaethesia as you note). In the former, I could literally be unconscious, and be schluffed out of the car, and I'd still be wherever I actually was, regardless of whether it was 'correct'. Is it just that I am conscious you're wanting to hang something on, in that example? — AmadeusD

I raised the example because I believe it to be disanalogous. In the Google Maps scenario you must judge that you have arrived. In the anesthesia scenario you need not judge that you should wake up. In that case you are literally woken up by someone else. In that case no volitional act is required, judgment or otherwise.

I agree that there are differences between recognizing that you have arrived at your destination, and deciding to take a taxi cab. But both are judgments given the definition I have provided. I don't think it makes sense to say, "I knew that I arrived but I did not judge that I arrived." When philosophers talk about judgment this is what they are talking about.

I don't quite think this is available to us, so I'm happy with that. — AmadeusD

Okay, but it seems that many of your complaints have to do with a lack of watertight reasoning due to vague definitions (e.g. "moral," "right," "judgment," etc.).

Correct. But I've designed a scenario where I am not engaged in the prior activity, in terms of judgement. I can judge that hte crash fucking sucked, but I made no attempts to divert, or incur a crash. — AmadeusD

It seems like you are saying that you might get in a crash and regret the crash, and then when someone asks you why you got in a crash, you could reasonably answer, "Oh, I didn't know I wasn't supposed to crash when driving. I make no attempts to avoiding crashing." That seems patently unreasonable, no? This all goes back to my claim:

To decide when to turn your steering wheel with your eyes closed in relation to the instructions you are hearing is a judgment — Leontiskos

The process here is something like, "I hear the instruction telling me to turn left, and then I turn left." For some reason you want to remove all judgment from that action, as if Google Maps turns the steering wheel for you and you do nothing at all. Or as if you put yourself on autopilot and cease to be an intermediating agent between Google Maps and the car. None of that seems reasonable. It seems pretty straightforward that when carrying out instructions one is engaged in judgments, even if they are subordinated to a proximate end and infused with an intention of trust. -

What is faithIt seems to me that the "ultimate concern" of any life governed by self-reflection is the basic ethical question "how should I Iive?" Could there be strictly empirical evidence available to guide me in answering that question? — Janus

Why would one suppose that either Tillich's "ultimate concern" or else the question "how should I live" are not guided by empirical evidence?

Here is your syllogism:

1. All science is X

2. No religion is X

3. Therefore no religion is scientific

In this case your X is "empirical." Elsewhere you have tried different X's. None of them seem to be sound. -

Positivism in Philosophy- It's pretty interesting to ask about the relation between Positivism and Pragmatism. They seem to be cousins, and at least some pragmatists are positivists who jumped ship when it began to sink.

-

Should we be polite to AIs?- :lol:

- I think folks who see AI as conscious and believe we owe it moral obligations are confused. Nevertheless, one might be "polite" to inanimate things for other reasons, for example, in the same way that they are respectful with a hammer. -

Positivism in PhilosophyMy position is that Pooper's (!) revision allows Positivism to be sustained until falsified, meaning it will survive contingent upon there being no facts falsifying it. — Hanover

So Popper talks about what "can be falsified," which is a possibility claim. It is a claim about falsifiability. Given that anything at all can be "sustained until falsified," it would follow that anything at all fulfills Popper's claim, construed in that way, which in turn would make that claim vacuous. Popper is asking whether it is able to be falsified, not whether it has been falsified. I think @Janus was struggling with this same distinction recently.

Note too that if something is not falsifiable then it obviously won't ever be falsified and this is another reason why the "has been falsified" consideration is not helpful. In that sense checking whether something has been falsified is precisely beside the point for Popper. If it has been falsified, then for Popper it is a scientific theory. In that case it passes his test of falsifiability. Popper's targets are those theories which have not been falsified and can never be falsified (because they are unfalsifiable).

(It is interesting to ask whether Popper's work remains within or moves beyond Positivism. I suspect that @Wayfarer might say that Popper's response is a kind of extension of Positivism.)

What makes it fail, as I alluded to, might be the lack of predictive value in such things as economic and psychological theories. That is the blow to Positivism I'd think meaningful, less so internal inconsistencies in its logic. That is, the proof is in the pudding of how it works. — Hanover

That looks like a pragmatic consideration, which is rather different than Popper's consideration. Popper's notion of falsifiability is separate from a notion of whether "it works." Non-empirical theories might work very well, depending on one's aim. The Logical Positivists would do well to reflect on how well their non-empirical theory succeeded in achieving their aims, and what those aims really were.

(Revised to clean up the argument.) -

Positivism in PhilosophyI'd suggest, from what you've written, that positivism does not fail under the Popper revision of falsifiability you've described. — Hanover

So you are claiming that under Popper's thesis "that a scientific theory is one that can be falsified by empirical evidence," Logical Positivism and its Verification Principle meet the criteria required to be counted as a scientific theory? How so? How is the Verification Principle able to be falsified by empirical evidence?

-

An interesting and useful thread, . :up: -

What is real? How do we know what is real?I don't believe that Aristotle was falsified by Lavoisier.

Falsification is a much more complicated maneuver than disagreement on fundamentals. Disagreement on fundamentals -- such as whether water is an element or not, or whether water is composed of atoms or not -- don't so much falsify each other as much as they both make claims that cannot both be true at the same time. This is because they mean different things, but are referring to the same object. — Moliere

If you believe that Lavoisier said something true, and that it contradicts Aristotle, then you are committed to the idea that Lavoisier has falsified Aristotle. You can't claim that and then simultaneously say that Lavoisier has not falsified Aristotle. So your reasoning throughout the thread to the effect that Lavoisier caused Aristotle's assertions to be false is sensible, given those conditions.

I would say with respect to reasoning about reality -- deciding "What is real?" -- the PNC is not violated, of course, but they can't both be true either. Water is either a fundamental element which does not divide further into more fundamental atoms, or it is a composition of other more fundamental elements and so does divide further, or something else entirely — Moliere

Okay, sure. Water cannot be divisible and indivisible. This is a true contradiction. Yet this is the first time I've seen you presenting Aristotle as a proponent of indivisibility. Earlier you were talking about teleology.

Again, if Lavoisier proved that water is divisible and Aristotle held that it is indivisible, then Lavoisier has falsified Aristotle. But this is different from what we were discussing earlier:

I think you've presented a canard of "teleology," but let's accept it for the sake of argument. Does "water is H2O" contradict "Water wants to sit atop Earth"? It looks like Lavoisier did not contradict Aristotle even on that reading. — Leontiskos

-

The thinkers are very far apart from one another in terms of time, who they are talking to, the problems they're trying to address, and so forth, and yet are talking about the same thing -- at least I think so. So the variance between the two can only be accounted for by looking to the meanings of the terms, which in turn is how we can come to understand how people have made inferences about fundamental matter in the past, and thereby can serve as a kind of model for our own inferences. — Moliere

Good, I agree. :up:

What water is seems to me more of scientific than philosophical question, but then I know that barrier is another bit where we're likely not in agreement, since for Aristotle the question of science and philosophy isn't as separate. His whole philosophy has large parts dedicated to ancient science and he's making use of philosophical arguments. — Moliere

There is no strict division between philosophy and science. Aristotle is generally referred to as a scientist, perhaps the first, and yet this does not disqualify him as a philosopher. Srap just deleted a great post on this in J's new thread, focusing on psychology and phenomenology ...lol.

is my most recent post to you, by the way. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?Yes, there are true sentences. — J

And do people who contradict those sentences hold to falsehoods? Do false assertions exist? Or have we managed a world where there are truths but no falsehoods? You seem to dance around these simple questions continually.

And if you are to say, "No, they probably just have a different context, and are not really contradicting anything at all," then do you have an actual method for determining when someone has contradicted a sentence and when they "hold to a different context/stance"? Because if you don't have such a method then I'm not sure how it is substantive to claim that they probably have a different context.

It's hard, perhaps, to take on board the idea that context is what allows a sentence to be true at all. If a Truly True sentence is supposed to be one that is uttered without a context, I don't know what that would be. — J

Psychologizing ad hominem is pretty easy. "It's hard, perhaps, to take on board the idea that some people are right and some people are wrong. If a Truly True sentence is supposed to be one that is immune to contradiction, I don't know what that would be. Given that people purport to disagree all the time, it would be pretty amazing if no one were actually disagreeing." -

Epistemic Stances and Rational Obligation - Parts One and Twoand thus undermine a stance's construal as "upstream" from facts and matters of ontology. — fdrake

Good post. The vagueness of a "stance" strikes me as a big problem, and this point about cordoning stances off from their downstream "effects" is a good example of that.

I would prefer Aristotle's Rhetoric or Newman's Grammar of Assent. In the Rhetoric Aristotle talks about "enthymeme," by which he means a "shooting from the hip" sort of argument (as one would be likely to hear when a politician tries to make a point given a very short bit of time). That sort of argument can hit or miss depending on the background conditions of one's hearers. Even Pincock's abductive reasoning would be a form of "enthymeme" for Aristotle.

The trouble with "enthymeme" is that it is a kind of per accidens argument. It is like tossing a hand grenade into the fray and hoping you hit someone. For this reason the phenomena surrounding that sort of argument isn't scientifically precise or predictable. Chakravartty can only pretend that a study of that sort of argumentation is scientific by talking about "stances" and pretending that he has some relatively precise notion of what he means by a "stance." He almost certainly does not. This tends to make his thesis vacuous, like the certitude that neither Alice nor Bob are irrational in their preferred sample size. -

Epistemic Stances and Rational Obligation - Parts One and TwoThis is sort of an interesting thread. I can see how it intersects with your interests, @J. Note that I am arriving from the citation in .

But I’ll cut to the chase and say that I think the argument as a whole can be defeated simply by denying the characterization of what a stance voluntarist does. Pincock’s language includes phrases such as “no reason that obliges them,” “not adopt[ing] their realist stance on the basis of any reasons that reflect the truth,” “no connection to the truth,” and “not appropriately connected to the truth.” These all-or-nothing characterizations can only hold water if we accept Pincock’s idea that a theoretical reason must result in rational obligation. (I should point out that the first phrase, “no reason that obliges them,” would be conceded by Chakravartty. But he would not concede that there are no theoretical reasons that could have a bearing, or influence the decision – merely that they don’t result in rational obligation, and that others could have different reasons for their stances, or weight them differently.)

As we know, Pincock maintains that the stance voluntarist has no theoretical reasons of any sort for their adoption of a stance. For Pincock, only “desires and values” can form the basis for (voluntarily) adopting a stance. Once again, if we look back at Chakravartty’s description of how he understands an epistemic stance, this seems to be a misreading: — J

Let's construe Pincock's argument as saying that, "Chakravartty has no reason to adopt one stance rather than another, when choosing among the subset of stances which are rational." This looks to be the most charitable interpretation, and it precludes the response that, "Choosing one stance involves 'rational choice' because one can produce reasons in favor of that stance."

Suppose all possible stances are represented by the set {A, B, C, ..., X, Y, Z}. And suppose that Chakravartty's set of "rationally permissible" stances is {A, B, C, D} (and therefore 4/26 stances are rationally permissible). Given this, my construal of Pincock's argument pertains to "choosing among the subset of stances which are rational," i.e. {A, B, C, D}. Chakravartty can say that he has a reason to adopt C rather than F, and that he has a reason to adopt C simpliciter, but he apparently cannot say that he has a reason to adopt C rather than D (which is what he needs to say if he is to properly answer Pincock).

This way of construing Pincock's argument has much to recommend it, given that it is in line with what is traditionally understood as "voluntarism." Namely, voluntarism posits that the choice in question is traced to the will rather than the intellect, such that one might explain their choice by saying, "I did it because I wanted to, not because I was rationally guided to do so." *

I think Chakravartty tries and fails to address this difficulty in section 3. We can boil it down with the dichotomy, "Either you have a reason for your choice or you don't" (where the voluntaristic answer that "I wanted to" does not count as a reason). Does Chakravartty have a principled (all-things-considered) reason to choose C and reject D? Apparently he can't have a principled reason, because if he did then D would not be "rationally permissible" (for him). The whole rationale for voluntarism—including stance voluntarism—is that the subset of rationally permissible stances ({A, B, C, D}) are equally rational, and are therefore immune to rational predilection. Voluntarism entails that a decision between C and D is not rationally adjudicable.

This constitutes an internal problem for Chakravartty, because at the end of his paper he assumes he is still entitled to the general idea that we should "encourage others... to see things our way":

To add to this dialogue the assurance that “I, not you, possess a uniquely rational epistemic stance” adds nothing of rhetorical or persuasive power. In contrast, to endeavor to elaborate, to explain, to scrutinize, and to understand the nature of opposing stances (to engage in what I call “collaborative epistemology”)—and to encourage others, when our own stances appear to pass the tests of consistency and coherence, to see things our way, upon reflection—is to do our best. There is no insight into epistemic rationality to be gained by demanding more than this. — Chakravartty, 1314

This is a nice moral sentiment, but it isn't rationally coherent. If the voluntarist claims that the subset of rationally permissible stances are not rationally adjudicable, then he is not rationally permitted to "encourage others" to drop their D and adopt his C, given that there are, by definition, no compelling reasons to choose C over D. He must restrict his stance-disagreements to those interlocutors who hold to one of the 22 stances which are not rationally permissible.

If Chakravartty wants to coherently "encourage others to see things his way," then he must reject his own voluntarism. He doesn't need to be an ass about it, but he must hold that, "My epistemic stance is more rational than yours." If he doesn't hold that then he has no grounds to try to convince his interlocutor to reject D and adopt C. If he is a true voluntarist then he would not argue against the stance of someone who holds to one of the four rationally permissible stances.

* Note that voluntarism signifies choice or will, but if the "values" that Pincock characterizes are inherited rather than chosen then everything I say here still follows. Any non-rational predilection for C will result in the same problem, whether that predilection is based on will, inheritance, or anything else. As long as Chakravartty cannot hold to A, B, C, and D all at the same time, he will be forced to possess one rationally permissible stance rather than another, yet without having a reason that counts as a worthy reason to choose among that subset of stances. Thus Pincock's point about the realist will also apply to Chakravartty himself, who sees himself to hold C rather than A, B, or D, for no good reason at all. This creates a deep incoherence between the non-rational stance and the "rational" effects that flow out of it. @fdrake is correct to note that the stance cannot be cordoned off in this way. In real life when someone notices that they have no good reasons to hold C, they simply stop holding it and end up trying to hold to the four rationally permissible stances equally.

(For the record, I find both authors to be rather confused, especially Pincock. So I'm not throwing in with Pincock. Pincock is using "rational obligation" in a softer sense than Chakravartty recognizes, but given that Pincock is clear about his usage the misunderstanding is on Chakravartty (unless the draft Chakravartty read was substantially different than the published paper). If Chakravartty thinks he possesses some coherent distinction between 'rational choice' and 'rational obligation', then the onus is certainly on him to make that distinction clear. It seems to me that he relies heavily on ambiguous and undefined terms, including "rational obligation.") -

What is real? How do we know what is real?The straightforward denial of truth, e.g. moral anti-realism, actually seems less pernicious to me here. Reason simply doesn't apply to some wide domain (e.g. ethics), as opposed to applying sometimes, but unclearly and vaguely. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, I agree. The straightforward denial of truth is certainly more transparent and coherent than the equivocal re-definition of truth.

As reason becomes a matter of something akin to "taste" it arguably becomes easier to dismiss opposing positions out of hand. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. This happened right in this thread, when @Moliere claimed that because Aristotle views water "teleologically" and Lavoisier views it as H2O, therefore Lavoisier has falsified Aristotle. Moliere—who it seems to me does not have a great grasp of the PNC—imputed contradiction where none exists. Often it is the case that if people had a better understanding of the PNC they would see that there is less disagreement than they suppose. The PNC is a remarkably mild principle. It allows an enormous amount of space for reason to play. -

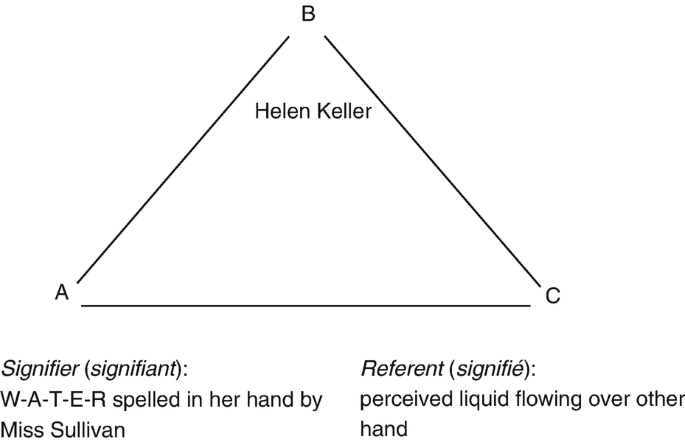

What is real? How do we know what is real?Percy emphasises that though Keller had felt water before, she lacked the symbolic framework—the naming of water via language—until that pivotal moment. — Banno

Yes, hence my whole point that the water goes before the 'water'.* Without some contact with water the sign 'water' has nothing to signify.

We'll have to disagree here. — Banno

If you want to say that dogs "understand" water and you want to take issue with the Aristotelian approach, then the first thing to do is to get clear on the difference between canine "understanding" and human understanding.

* At the very least, causally -

In a free nation, should opinions against freedom be allowed?The performative contradiction is in performing a democratic act by someone who perforce rejects democracy. — SophistiCat

But why assume they reject democracy? Maybe they say, "I think democracy is the wrong system for our nation; I will vote against it; I hope the vote succeeds and the nation is no longer democratic; if the vote does not succeed I will abide by the decision."

To say that it is a performative contradiction for a society to vote itself out of democracy is to reify a democracy into a being of its own. The reification is fictional; the democracy does not destroy itself; rather, citizens are opting for a different form of government.

Given that democracies can legally disband themselves via amendments to the legal charter, do you think that provision means that the charter is itself self-contradictory? Surely there is a difference between, say, legally disbanding a contract and illegally disbanding a contract. One can honor the terms of a contract while simultaneously seeking that it be dissolved. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?Ah, I think I see the misunderstanding. You're using "pluralism" and "relativism" interchangeably and synonymously, where I'm drawing a distinction. Do you think I shouldn't do so? Pluralism, as I understand it, allows different epistemological perspectives, with different conceptions of what is true within those perspectives. It also encourages discussion between perspectives, including how conceptions of truth may or may not converge. Relativism (about truth) would deny even this perspectival account as incoherent. (A very broad-brush picture of a hugely complicated subject, of course.) — J

Classically, if X is true then everything which contradicts X is false. Since both pluralism and relativism reject this notion, the person who wants to avoid truth claims is aligned with pluralism and relativism (at least so far as this consideration goes).

Similarly, if one wants to oppose pluralism or relativism, the most straightforward way is to say, "There are truths and the principle of non-contradiction holds." We could adapt @Count Timothy von Icarus' challenge to you as follows: If this standard way of opposing pluralism and/or relativism is unavailable to you, then on what grounds do you disagree with pluralism and/or relativism?

(We could ask whether pluralism entails relativism, but the simpler approach is to focus on relativism itself and leave pluralism on the back burner.)

As Spinoza said, "Omnis determinatio est negatio." -

What is real? How do we know what is real?I was just thinking of more straightforward examples, like if we had never seen an animal, nor any picture or drawing, it could still be described to us. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Like, "Water is transparent"? It seems like my example is an instance of this, but I am certainly open to other concrete examples.

It may be confusing that I used the word "sensible" . I was using it metaphorically. The point was not that we cannot have an indirect understanding of water, say, through a proposition about transparency.

The causal priority of things is needed to explain why speech and stipulated signs are one way and not any other. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, I agree.

I think that's a difficulty with co-constitution narratives as well. They tend to make language completely sui generis, and then it must become all encompassing because it is disconnected from the rest of being. I think it makes more sense to situate the linguistic sign relationship within the larger categories of signs. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think someone might say the chicken came before the egg, and another person might say that they know of a chicken that came from an egg. As you say, the priority is causal. The claim is not that no chickens come from eggs.

Co-constitution, especially in the context of my discussion with Moliere, looks to be a quibble. Even in the case of language acquisition it usually isn't true. For example, a child's first words are never co-constituted with the reality they signify.

But the point I was making with Moliere is <If one does not have familiarity with water, then they will not be able to use the sign 'water' successfully>. ("Successfully" is a better word than "sensibly.") Both Aristotle and Lavoisier are assuming that the substance water has a precedence to our understanding of it, and that is the key. If there were no external substance of water then @Moliere's argument would hold good. In that case there would be no adjudicability between Aristotle and Lavoisier.

But learning to drink and wash is itself learning what water is. There is no neat pre-linguistic concept standing behind the word, only the way we interact with water as embodied beings embedded in and interacting with the world. Our interaction with water is our understanding of water. — Banno

The problem here is that it commits you to the idea that dogs and ducks understand water, when in fact they don't. Walker Percy's study of Helen Keller vis-a-vis his own deaf daughter bears out the fact that Helen's understanding of water was not present until she was seven years old—long after she had been interacting with water. Interaction is not understanding; language does aid understanding; but one will not be able to successfully use the sign 'water' if they have no familiarity with water (either directly or indirectly). It can be said that the sign and the sign-user emerge simultaneously, but it remains true that the signified is causally prior to the sign, in much the same way that the non-sign-user (e.g. Helen before she was 7) is prior to the sign-user (e.g. Helen after she reached age 7). Much of this goes back to the quote. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?But is that right? That "Water before word" or "Word before water" exhausts all the possibilities? — Banno

But this is a strawman. No one has said that there must be a temporal precedence between encountering water and encountering the word 'water'. The point is that one does not use a word like 'water' correctly if they have no familiarity with water, and yet one can certainly have familiarity with water without having familiarity with the word 'water'. There is a causal precedence between water and 'water', not a temporal one (although in most cases one will encounter water before encountering 'water'). -

What is real? How do we know what is real?- Right... I guess I would need you to set out the thesis that you believe to be at stake. I wrote that post with your emphasis on falsehood in mind. You have this idea that Lavoisier must have falsified something in Aristotle. The whole notion that we can grow in knowledge presupposes that we have something which is true and yet incomplete, and which can be built upon.

For myself it seems that if we accept a realist metaphysics, and our meanings change, then we have to accept the very real possibility that most of what we know is false -- that it's "good enough" to begin with setting out a problem or understanding something... — Moliere

It is odd to say that it is false. If it is "good enough" to begin understanding, then it simply cannot be wholly false. If it is wholly false then it is not good enough to begin understanding.

If I know something about water, and then I study and learn more about water, then what I first knew was true and yet incomplete. It need not have been false (although it could have been). Note, though, that if everything I originally believed about water was false, then my new knowledge of water is not building on anything at all, and a strong equivocation occurs between what I originally conceived as 'water' and what I now understand to be 'water'.

For Aristotle learning must build on previous knowledge. To learn something is to use what we already know (and also possibly new inputs alongside).

I agree that Aristotle would accept and expect this -- but I don't think he'd predict what's different. — Moliere

Right. He knows that there is more to be learned about water even though he does not know that part of that is H2O.

But then, in comparing the meanings between the two, it doesn't seem they mean the same thing after all... even if they refer to the same thing, roughly. — Moliere

Right, good. Let's just employ set theory with a set of predications about water:

- Aristotle: Water: {wet, heavy unlike fire}

- [Call this AW]

- Lavoisier: Water: {wet, heavy unlike fire, H2O}

- [Call this LW]

On this construal Lavoisier's understanding of water agrees with Aristotle in saying that water is wet and heavy unlike fire, but it adds a third predication that Aristotle does not include, namely that water is composed of H2O.

What is the relation between AW and LW? In a material sense there is overlap but inequality. Do Aristotle and Lavoisier mean the same thing by "water"? Yes and no. They are pointing to the same substance, but their understanding of that substance is not identical. At the same time, neither one takes their understanding to be exhaustive (and therefore AW and LW do not, and are not intended to, contradict one another).

Now the univocity of the analytic will tend to say that either water is AW or else water is LW (or else it is neither), and therefore Aristotle and Lavoisier must be contradicting one another. One of them understands water and one does not. There is no middle ground. There is no way in which Aristotle could understand water and yet Lavoisier could understand it better.

If one wants to escape the problematic univocity of analytical philosophy they must posit the human ability to talk about the same thing without having a perfectly identical understanding of that thing. That is part of what the Aristotelian notion of essence provides. It provides leeway such that two people can hit the same target even without firing the exact same shot, and then compare notes with one another to reach a fuller understanding. - Aristotle: Water: {wet, heavy unlike fire}

-

In a free nation, should opinions against freedom be allowed?To agree democratically to abolish democracy seems like a performative contradiction. When I elect a party different to the one you want I haven't taken away your freedom, and your party can always win the next election. But a democratic vote to abolish democracy, if it were not supported by everyone, would illegitimately abolish the freedom of those who opposed it. If absolutely everyone agreed to abolish their freedom then it might be okay, but then what about those yet to reach voting age? — Janus

Unless you want to say that democratic votes require unanimity, they do not illegitimately abolish the freedom of those who voted differently.* In a majoritarian democracy a majority consensus is required; in a super majority democracy a super majority consensus is required; in a unanimous democracy a unanimous consensus is required. There is simply no reason why a democratic consensus must be unanimous in order to be valid. I would say that if a democracy cannot be democratically disbanded then it is not a democracy at all. But of course democracies can be democratically disbanded, in most cases according to the formal rules of the democracy itself.

If a democracy votes to disband itself, then the last act of that democracy is the act of disbanding. The act of disbanding is a democratic act. There is no performative contradiction here; there is just a majority of people who decide to order their political arrangement differently.

* In all likelihood you are conflating democracy with liberalism and particularly with a governmental defense of natural rights. But the idea of unalienable rights is not democratic - it does not flow from democracy. In fact it is undemocratic in the sense that it places a constraint on the democratic principle. Democratic rights are always alienable. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?- I don't think anything you said followed from anything I said, which seems standard at this point. You've gotten to the point where you're not even reading posts.

-

What is real? How do we know what is real?Yes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water." Familiarity with water is a precondition for familiarity with the English sign "water." — Leontiskos

I agree as a rule, although the tricky thing is that one might indeed become familiar with something first through signs that refer to some other thing. We can learn about things through references to what is similar, including through abstract references. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'm not so sure. What would an example be? That we become familiar with transparency, and because water is transparent our familiarity with transparency is therefore familiarity with water?

I would say that familiarity with transparency is not itself familiarity with water. Nevertheless, someone could say, "You don't know what water is, but you know what transparency is, and you should trust me when I tell you that water is transparent." We can learn something about water through this sort of trust (and philosophy is always built on faith of this kind), but on my view this counts as "familiarity with water" (via someone who has knowledge). Once even that sort of second-hand familiarity is in place the English sign "water" is available to us, at least in a limited sense. Still, this won't work if our source has no familiarity with water.

(I suppose I am also presuming that the one who takes on faith the claim that water is transparent is also differentiating between water and 'water', and is thus aware that their source is making use of a sign.)

And the difference between these two models lies in the question: in the second model, what is signified: the object, or an interpretation called forth by the sign (the meaning)? That seems to be the essence of the question here to me. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is good. I would only add that Walker Percy's simplified triadic model may be helpful in a place like TPF, given that even skeptics are generally able to admit that not every sign-user has an identical understanding of every sign:

---

- :up:

I would simply want to ask @J what his telos is. What is his aim? Truth? Pluralism? The moral avoidance of strong knowledge claims (which might create conflict)? And if he is aiming at multiple different things, then the question is whether those various aims are mutually consistent.

For example, his claim that he is not a relativist (and that he believes in truth) is somewhat at odds with his conviction that strong truth-claims are morally problematic. Perhaps he solves the riddle by defining truth as intersubjective agreement, but the difficulty there is that we all know that there is a difference between intersubjective agreement and truth, and that we are even at times morally obliged to disregard or even oppose the falsehood represented by the intersubjective agreement.

At the end of the day I would simply say that although we must avoid injustice, nevertheless it is not unjust to affirm what one believes to be true (at a general level). Even with something like racism, it is not unjust when it is in earnest, as some of the cases that Daryl Davis engaged demonstrate. One must be mindful of the ways in which they engage others, but to earnestly believe that something is true is never unjust. One might even avoid pronouncing a truth for the sake of some communal good, but it does not follow that one should not hold the thing as being true. The reason the left frets over this sort of thing is because they conflate per se and per accidens causality and implication. -

How do we recognize a memory?My only objection here would be to ask whether this happens fast enough to constitute the complete explanation of recognizing a memory. — J

A good way to approach this is through shape recognition. If I present you with a triangle or a square, will you be able to recognize the shape immediately, without discursive reasoning? Presumably you can. But a young child who is learning their shapes apparently cannot do this. They have to do things like take wooden blocks and see whether they fit in differently shaped empty spaces. They engage in empirical exercises and eventually come to better understand the notion of shape, which in turn grows into shape recognition.

We might ask, "Is the recognition of a shape a discursive or a non-discursive act?" The answer is both or neither. We actually have the ability to "automatize" complex processes into simple acts, and the fallibility of the act follows the fallibility of the process (i.e. we can also automatize false or invalid processes). Life is complex, and not everything is like this, but it seems to me that memory recognition probably is (yet in an inevitably more complex manner).

(It may be worth noting that this "automatization" is different than intellection.) -

What is real? How do we know what is real?In order to talk about what is real we need to know what it is we mean by "What is real?" -- this would be before any question on essentialism. In order to talk about what water is we have to be able to talk about "What does it mean when we say "Water is real", or "Water has an essence"? or "The essence of water is that it is H2O"?" — Moliere

Yes, in a way, but I think reality comes first. I think we have to have some familiarity with water before we have any sensible familiarity with "water." Familiarity with water is a precondition for familiarity with the English sign "water."

We can't really deal with any dead philosopher without dealing with meanings -- the words have to mean something, rather than be the thing they are about. — Moliere

I think the key here is that when Lavoisier says, "Water is H2O," he could be saying two different things:

M: "Water is H2O, and if anyone, past or future, says anything else about water, they are wrong."

N: "Water is H2O, and there are all sorts of other true things that can be said about water."

You seem to take Aristotle to have said something like (M), but that's not generally what a scientist means when they say, "Water is such-and-such." If all scientists are saying things like (M) then there can be no growth in knowledge and therefore Aristotle's approach is wrong. But given that scientists are usually saying things like ( N) there is no true barrier to growth in knowledge - either individually or communally.

Whether they falsify one another or not is different from whether they mean the same thing. I don't think they do, but are probably talking about the same thing in nature. I do, however, think you have to pick one or the other if we presume that Lavoisier and Aristotle are talking about the same thing because the meanings are not the same. The lack of falsification is because the meanings are disparate and they aren't in conversation with one another, and they aren't even doing the same thing. — Moliere

Much of this is right, but again, the crucial point you are failing to recognize is that neither Aristotle nor Lavoisier mean that anyone who does not mean what they mean must therefore be wrong. That is a very strange reading. No one is claiming to have a complete and exclusive understanding of water.

It's the difference in meaning that raises the question -- if the thing is the same why does the meaning differ? — Moliere

Because learning occurred and knowledge grew. Lavoisier knows more about water than Aristotle did. Aristotle would expect this to be the case for later scientists. -

How do we recognize a memory?Yes. My only objection here would be to ask whether this happens fast enough to constitute the complete explanation of recognizing a memory. But as T Clark and I were discussing, this stuff can happen very quickly beneath conscious awareness. — J

Sure, for example:

In a more general sense I think it is important to recognize that contextual situatedness can be intuited in a moment. One does not need to survey, analyze, and engage in induction in order to understand whether something tends to be contextually situated and integrated within increasingly large spheres of influence. — Leontiskos

You might do this very quickly and automatically. — Leontiskos

In general I would say that the mind is not as discursive and time-bound as our age tends to believe. I think this is probably a huge underlying issue on the forum, not unrelated to intuition and intellection.*

I think I agree with this, but let me clarify: "not allowed to survey anything [else]" means you could look at the photographs but, per impossibile, not allow any associations to form in your mind? And "contextually inform" means respond as we normally do, with a fully functioning mind? If so, then yes, this seems right. — J

Yes, that's right, such as the example I gave where you are not allowed to let the pixels coalesce into an image of your mother.

The thesis is that the photograph from the party you attended will possess a different "contextual situatedness" than the photograph from the party you did not attend, and that this is why you remember the one but not the other.

What is your own theory of memory recall or memory recognition?

* Edit: But if you want to think about the fallible "mark" of a memory, this is how I would approach that:

The intentional stance with which we approach a memory may give it a "pastness" color that even dyes it either temporarily or indelibly. If this is right then a confabulation probably becomes more solid each time someone surveys it and (falsely) views it as a memory. — Leontiskos -

What is real? How do we know what is real?either the thing has both meanings — Moliere

I would say that things don't have inherent meanings (at least for philosophy). I think you are still conflating metaphysics with linguistics. Throughout this post you talk a lot about "meanings," but essentialism is not about what words mean, it is about what things are.

1. The essentialist would be likely to say that water is H2O (or that water is always H2O).

1a. The essentialist would say that the term “water” signified H2O before 19th century chemistry. — Leontiskos

In (1) the essentialist is talking about a thing, water. In (1a) the essentialist is talking about a sign, "water." You are still talking about the meaning of signs, such as "water," at different times throughout history.

Neither Aristotle nor Kripke are merely talking about what a word-sign means.

For myself it seems that if we accept a realist metaphysics, and our meanings change, then we have to accept the very real possibility that most of what we know is false — Moliere

I've already pointed out that Lavoisier's discovery did not necessarily falsify what came before:

↪Moliere - Okay, great. And for Aristotelian essentialism this is taken for granted, namely that we can know water without knowing water fully, and that therefore future generations can improve on our understanding of water. None of that invalidates Aristotelian essentialism. It's actually baked in - crucially important for Aristotle who was emphatic in affirming the possibility of knowledge-growth.

This means that Lavoisier can learn something about water, in the sense that he learns something that was true, is true, and will be true about the substance water. His contribution does not need to entail that previous scientists were talking about something that was not H2O, and the previous scientists generally understood that they did not understand everything about water. — Leontiskos

When Lavoisier talks about water he is talking about a thing, not a word-sign. He is interested in the reality of water itself. -

How do we recognize a memory?Yes, it's hard to know what is typical here. Perhaps I'm given to daydreaming! For whatever reason, the "unannounced or contextless memory" phenomenon is common for me, which is probably why I got curious in the first place about how we recognize a memory. — J

Yes, fair enough.

Or another metaphor: Let's say a memory is situated within its causal nexus in the same way as a rock that has been thrown. There it sits, on the ground, having been thrown. Another rock, nearby, is so situated as a result of having been excavated around. So, different causal stories and contexts, but we couldn't tell which was the case just by looking at the rock, or at least not readily. That's the question I was raising -- would the memory (rock #1) still be recognized as a memory if the only thing that differentiated it from an image (rock #2) was its causal context? — J

When I used the term "causal nexus" I was careful to make it secondary, after the more primary sense of "contextually situated." After thinking about your conversation with Count Timothy and the way you view causality in a very specific sense, I somewhat regretted using the idea of causality at all.

So the first thing I would say is that a causal nexus is not merely a causal history, although it could include that. The second thing I would say is that for someone like yourself who has a very specific understanding of causality (i.e. efficient causality), it would probably be better to talk about contextual situatedness.

How is a memory contextually situated? Some ways come to mind: via chronology and via the associations noted (sensual, proprioceptive, intellectual, teleological...). Like a spider's web, if you pull on one thread the whole thing starts to move, because it is a part of an integrated whole. We know what it's like to pull on that sort of thing as opposed to pulling on the silk thread of a larvae. It's different.

Regarding your rocks, a static image or snapshot will tend to lack context. If you see two photographs of two different Christmas parties, and you are not allowed to survey anything other than the two photographs, then it will not be possible to determine whether you were at one of the parties. Only if you are allowed to contextually inform the photographs will you be able to recognize one or both. For example, if you are allowed to recognize a subset of pixels as the image of a person, and you are allowed to recognize the image of the person as the image of your mother, then you can begin to contextualize and make sense of the photograph. Then you will be able to contextually situate the scene from the photograph within your own memory and decide whether or not you were present at the party. But the possibility of remembering will be impossible insofar as we limit ourselves to a contextless datum, whether it be a set of pixels, or a static photograph, or a randomly presented image. A memory is a part of a whole, and parthood cannot exist without context. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?Certainly, discussions of logic and the form of arguments and discourse can inform metaphysics. But I think the influence tends to go more in the other direction. Metaphysics informs logic (material and formal) and informs the development of formalisms. This can make pointing to formalisms circular if they are used to justify a metaphysical position. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that's exactly right. I think the reason Analytic philosophy likes "possible worlds" is because its reified formalism is logically manipulable in a very straightforward way. On that single criterion it is better than Aristotelian essentialism. But in no other way is the notion of "possible worlds" more helpful or intuitive or functional then the notion of "essence." The common person will use the latter and hardly ever use the former. The claim that "possible world" means something substantive relies on circular reasoning. The notion of possibility is entirely impotent without some undergirding metaphysics. -

What is faithFacts are supported by evidence, faith is not. By 'evidence' I man 'what the unbiased should accept'; that is what being reasonable means. — Janus

This is what I spoke to in the .

We all hold beliefs for which there can be no clear evidence. To do so is not irrational, but those beliefs are nonrational, not in the sense that no thoughts processes are involved, but in the sense that the thoughts are not grounded in evidence. — Janus

And this is what I spoke to in the last section of that post.

For most people, myself included, to believe X is true without possessing evidence for X being true is irrational. You don't think it is. Now I do not want to adopt your premise arguendo, and the reason I don't want to do that is because the premise is not generally accepted by others in the thread. I think it would be misleading for me to adopt that premise arguendo, because both myself and the many anti-theists would see it as accepting, arguendo, the premise that faith is irrational.

not in the sense that no thoughts processes are involved, but in the sense that the thoughts are not grounded in evidence. — Janus

There are epistemological problems here, and they center around the question of what the difference is between evidence and (subjectively) justificatory "thoughts." I think this problem runs deep in the thought of strong coherentists such as yourself. has targeted this problem in some detail.

But let me lay out a very common Christian approach to the issue you raise. The idea is that there are reasons and arguments that are undeniable (i.e. demonstrations proper), and then there are other kinds of reasons, which incline one towards a conclusion but do not demonstrate the conclusion undeniably (or "beyond any shadow of a doubt"). We could call these latter reasons defeasible reasons. An act of faith relies upon inferences and reasons that are defeasible and not undeniable (or indefeasible). But note that a defeasible reason does count as evidence, at least if we are to use "evidence" in the way that it has been used throughout human history. Faith involves rational underdetermination; the motives of credibility do not force the mind to believe. (Note that what I say here is technical, and must be read with precision.)

(This is why Christians believe that faith cannot be coerced; because motives of credibility are not demonstrations. Or more straightforwardly, because salvation involves the will and not only the intellect.) -

Beyond the PaleNo. I decided to trust the app. It tells me - I obey the relayed information. Note that I could be in Guam. But i judged the app to get me to wherever you live. — AmadeusD

Sure, you can decide (judge) that the app is to be trusted. Sort of like how you can trust a taxi cab driver to get you to your destination. Still, at the end of your journey you still have to judge that the app or cab driver is telling you that you have arrived (even though you are trusting them at the same time).

A case where no subordinated judgment occurs would be when you go under general anesthesia for surgery, simply trusting that you will wake up on the other side. Waking up is not a judgment, and so in that case there is only one act of trust-judgment. You are trusting that the judgments of others will cause you to wake up.

Yes, I can see why too. But I think jdugement should be a little more circumscribed to capture how it is used. — AmadeusD

Similar to "moral," philosophical definitions of "judgment" are going to be more precise and encompassing than colloquial definitions. That's why I used the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. If we go with colloquial definitions then we will run into things like the Sorites paradox mentioned earlier, and the reasoning will not be watertight. We can do that if we like, but then we no longer have a warrant to complain that the reasoning isn't watertight. If we want watertight reasoning then we must abandon vague definitions.

Nah, that's input-> output in this scenario. If I crash, I crash. — AmadeusD

It would be rather strange for someone to try driving somewhere and not care if they crash. To crash would be to fail to achieve your goal, and therefore you are generally always trying not to crash when you are driving somewhere. -

How do we recognize a memory?Leontiskos talked about context and I think that is a better way of putting it than how I did. Everything in the mind is cross-connected. Memories are not stored in one place. They are connected with other memories of the same or similar events, places, and times. Those connections are non-linear - they're not organized in the same manner we might organize them if we did it rationally, chronologically, or functionally. — T Clark

Yes, I think that's a good way of putting it. A memory has a kind of organic embeddedness, a bit like a single strand of a spider's web.

Maybe we could try to approach this from the negative: what's the difference between not being able to imagine something, and not being able to remember something?

For me, what I expect to be lacking with a memory is a good deal more specific than what I'm lacking when I'm trying to imagine something. A gap in the memory is usually surrounded by other memories: there's something very specific that's not there. Meanwhile not being able to imagine something indicates a lack of experience - it's more fuzzy. It feels like the difference between closing in on something, vs. casting out for something. — Dawnstorm

This seems like a fruitful way to approach the question. :up:

I'm asking about the experience of having a memory come to mind. (To keep it manageable, let's say it's an unbidden mental performance that comes up at random, as I go through the day.) — J

I think it's worth noting that this is a very specialized question, at least if what I say is correct (namely that "memories don't generally arrive unannounced" and unelicited).

This is probably true, but is the kind of differentiation such that it would be recognizable in experience? I'd like to see more discussion of this. — J

Well, to continue with the "strand in a spider's web" metaphor, I think it is recognizable. I think a strand-within-a-web is recognized as different from a strand-without-a-web.

You could think of this in terms of navigability. We can navigate from a strand in a web to other parts of the web, whereas we cannot navigate from a strand-without-a-web. Or at least it is much harder. And I don't need to go through a lot of discursive exercises in order to know the difference if I am standing on a strand.

I think modern (Cartesian) philosophy has a desire for clarity which obscures the capacity of the mind for recognizing this sort of contextual situatedness. The notion of navigability is not a binary, not a crystal-clear marker. That's why I said that certain kinds of dreams can be very discombobulating (because they possess their own contextual situatedness, navigability, integrity, duration, sovereignty, etc.). Or in other words, it is hard for the modern to say what they are looking for even after they admit that they are not looking for infallible certainty.

Consider a corollary. It is sometimes claimed that in the moments before death people can have extremely long, detailed, and coherent dreams. If someone had one of these dreams, and it managed to mimic the resolution and duration and complexity of an entire life, then how would the person discern which "experience-narrative" was their real life and which was the dream? On my theory, they couldn't (or else it would be very hard), because each experience-narrative possesses its own robust contextual situatedness. On the other hand, when waking up from a superficial dream we find that it is much harder to "inhabit" that space as real, given its arbitrary contextual boundaries. -

RIP Alasdair MacIntyreCheers to MacIntyre.

Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him.

I hadn't heard that he was declining. -

What is faithThat hope and love are intertwined in faith indicates that its function has to do with human bonding rather than salvation. — praxis

This is a good example of an assertion with no attached argument. I'm not sure why you would think this. An argument would provide me with some insight.

Why should salvation require faith? — praxis

Are you at all familiar with Christian theology? Or the Reformation polemics? I'm not sure where your starting point is. -

What is faithWhat do you think that implies? — praxis

Here is the quote in context. It seems pretty transparent:

So what I am saying above is, when I think of religious faith, I think of moms and dads loving their kids. The point being love.

Many on this thread, when they think of religious faith seem to think only of Abraham attempting murder, terroists bombing schools, etc. — Fire Ologist

Here is a quote from the OP of the whole thread:

6) Finally, why do Christians argue whether faith must have hope and love in order to cause salvation? Are not those three things always intertwined together? — Gregory -

How do we recognize a memory?Yes, this "pastness" may be the very thing I'm calling the "feature" of an alleged memory, by which we recognize it as such. But I'm asking further -- what is it? What is the experience of pastness? — J

I'm not convinced that it is a mark so much as a kind of intuitional inference.

Suppose you can see the future. A "thick image" comes to your mind. It could be a memory of the past, a foreseeing of the future, a memory from a dream, or a mere mental image. You know that it is not a present experience, in the sense of an experience of the actual world that will in turn form a memory.

If the thick image arrives unannounced you will basically decide which it is through a process of elimination (and determining when a memory is indexed requires the same sort of process). You might do this very quickly and automatically. But memories don't generally arrive unannounced. Usually we call them up on purpose or else they are elicited by an intelligible association or cue. Because memory access is not random, there is usually a reliable process to sort out the different categories of "thick image" (i.e. things involving the depth I noted earlier). The intentional stance with which we approach a memory may give it a "pastness" color that even dyes it either temporarily or indelibly. If this is right then a confabulation probably becomes more solid each time someone surveys it and (falsely) views it as a memory.

Leontiskos

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum