Comments

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsHeh. The normally reserved New York Times has dropped all pretense of impartiality:

Trump lies in the White House briefing room, and the networks pull the plug.

President Trump broke a two-day silence with reporters to deliver a brief statement filled with lies about the election process as workers in a handful of states continue to tabulate vote tallies in the presidential race. — NYT

I browse NYT regularly (usually just morning briefing Europe), and I've watched with mixed feelings their evolution from the first time when they dropped the L-bomb (there was an article from an editor at that time, explaining why they thought it was appropriate to say that Trump lied, as opposed to using a more neutral word) to this. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsMy early prediction (from before the pandemic) was that Trump would win reelection with a bigger margin (winning the popular vote as well). The sad thing is that in all likelihood, the main reason he isn't doing so well now is that the pandemic happened at the worst possible time for him. And what is hurting him is not his administration's incompetent and erratic handling of the response, but the fact that when times are hard - and they would have been hard even with the best possible response, for a number of reasons - people tend to allocate some blame to those at the top, regardless of how much or how little they are actually responsible. Any leader would have lost popularity after nine months of misery and at the height of the second (or is it third?) wave of the pandemic.

-

What would a mantis shrimp see through a telescope pointed at the cosmos?Yeah, we don't even know all that much about how animal eyes work - color resolution, etc. We have some idea, but there is considerable uncertainty there. As for vision at the level of cognition, my guess is that we know much less than that. And what we can learn would be expressed in the language of neuroscience or psychology, which isn't the same as conveying "what it feels like."

-

What would a mantis shrimp see through a telescope pointed at the cosmos?Yes, we are well aware of that. Even ordinary photo-video media (film, digital sensors) don't have the same light sensitivities as the human eye, and that has long been known and accounted for in various ways. But while in a consumer photo camera, for example, you want maximum fidelity to human perception*, when it comes to scientific imaging we have been sensing far outside the human range, and for a long time. Radio telescopes, for example, have been around since 1930s (says Wiki). On Earth we also use a wide spectrum of EM radiation, magnetic fields, ultrasound, electron beams, gravity sensors and other creative sensing techniques.

* Fun fact: digital cameras include an infrared filter, without which they would be picking up IR light. If you have an old digital camera that you aren't afraid to break, you can try and remove it yourself - and presto, you can now take pictures in the infrared spectrum! -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionI am not sure. The motivation for the Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory is to have a time-symmetric formulation of classical electrodynamics, right? Both Type I and Type II absorptions are symmetric, but I don't see why you have to have both, and not just Type I. Type I is just an interpretation of classical electrodynamics, since it is formally equivalent to it. Type II constitutes a net new addition to the theory, for which we have no evidence.

Of course, if it could be tested and confirmed, that would be quite remarkable. Cramer says (referring to earlier analyses) that if both types occur, one of them is expected to dominate - presumably, Type I in our case. But that still leaves a possibility of some Type II absorptions. Do you think it's likely that they would have gone unobserved/unnoticed all this time? How difficult would this be to test? -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionI was just rereading part of the paper on type II emission and absorption events, which are interesting. If we take the emitter to be atom 1, the absorber to be atom 2, and the emission to be a photon, from the lab frame it appears as a photon (its own antiparticle) from the origin is absorbed by atom 1 (the emitter) and then, seemingly unrelatedly, atom 2 emits a photon of the same energy, which continues forever.

If the distance between the two atoms is L, the time between perceived absorption and emission (actually emission and absorption) will be L/c. So if type II is possible, it ought to be detectable experimentally in principle, though in practice it would be hard if the phenomenon is limited to CMB radiation (assuming that's all that could constitute a photon from the origin).

What's more interesting is the idea that causal relationships between events can be apparently unmediated in principle. — Kenosha Kid

I wonder why he thinks that Type II emission is equally possible as Type I. Type I is an interpretation of a well-studied phenomenon (emission/absorption of EM radiation), while it takes work to explain away Type II. What's the rationale in proposing it? Just a general preference for symmetry? -

How do I get an NDE thread on the main page?Well, Sam put a good deal of work into his posts, and he actually made philosophical points, not just jee-whiz, isn't it special. He was a crackpot and his arguments were crap, but that's for others to decide.

-

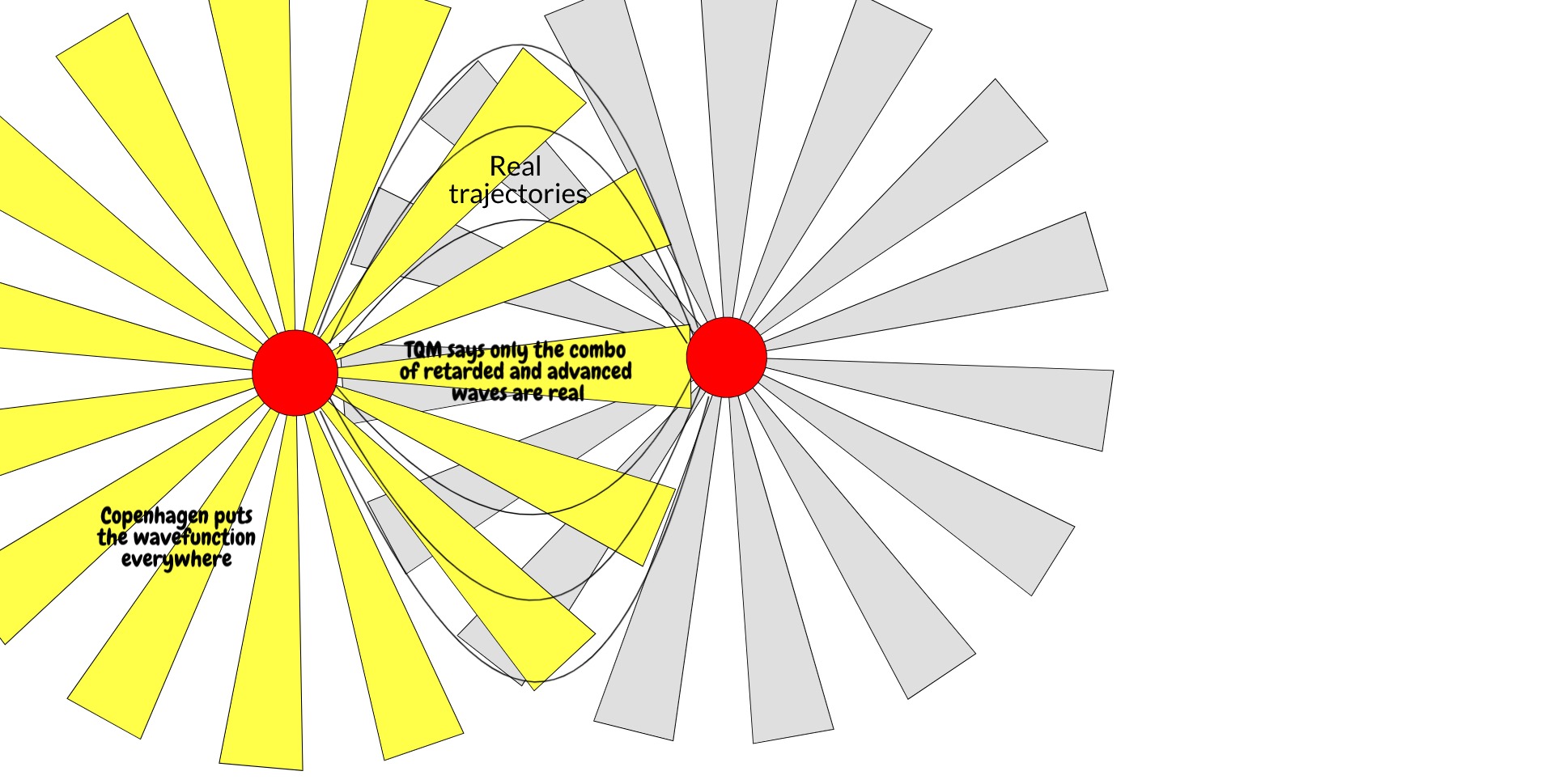

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionIn TI the electron is still essentially its wavefunction, right until its inglorious end. So it will go through both slits, interact with itself, etc. The twist is that there are two interacting wavefunctions - retarded and advanced. You can go with Feynman path integral formulation for the wavefunctions (as I think would be @Kenosha Kid's choice), but that is detachable from TI itself.

It being a wave (waves) takes care of some well-known interpretational challenges that trade on the wave-particle ambiguity, like delayed choice and quantum eraser. That said, some challenges have also been proposed that are specific to TI, such as the quantum liar experiment. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and Transactionthere are a number of alternative relativistically invariant wave equations, at least one of which is first order in time — SophistiCat

But also first order in space, I think? So the four solutions (advanced spin up, advanced spin down, retarded spin up, retarded spin down) reduce to two (advanced and retarded). — Kenosha Kid

He mentions a "relativistic Schrodinger equation," which has has a (P2 + m2)1/2 term.

Sure, but scattering also obeys the Pauli exclusion principle, so there must be two holes: one for the scattering electron to go to, and one for the scattered electron to go to (see the Feynman diagram in the OP). And those scattered electrons can scatter again, each requiring two holes, and so on and so forth. So it's a proliferation of backwards hole emission and transmission events. — Kenosha Kid

Does the incoming electron always scatter on another electron? If it's a solid that it interacts with, wouldn't it be something more complicated? Anyway, let's run with the assumption that in any type of interaction the electron is constrained by the requirement of having a (potentially infinite) chain of suitable boundary conditions.

No, because the probability distribution of the incident electron will still multiply the probability distribution of acceptor sites. — Kenosha Kid

Not if there is only one available site - in this case the electron wavefunction becomes irrelevant. The electron wavefunction removes at most a measure-zero amount of potential interaction sites, so without loss of generality we can assume that for any incoming electron, every point on the screen is available before we consider the conditions at the screen. But if the conditions at the screen are such that only one site is available, then that is what will dictate the actual distribution of impacts, not the electron wavefunction.

In case of "not many" available sites, the impacting distribution will factor in, but it will be smeared. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and Transactionsome relativistic formulations of the wavefunction equation have two solutions: w and its complex conjugate w* — SophistiCat

All, I believe. — Kenosha Kid

I was hedging because in his 1980 Phys. Rev. D paper Cramer writes that for particles with spin other than 1/2, e.g. bosons, there are a number of alternative relativistically invariant wave equations, at least one of which is first order in time. I don't think he considered the full QFT formulation though.

The advanced wave must be similarly causal but in reverse. For an advanced wave to be emitted from a particular point on the screen (describing an electron hole in reverse), that point must be capable of doing so. Otherwise the retarded wavefunction depiction of the electron leaving the cathode is unjustified in the first place. — Kenosha Kid

Are there really any absolutely forbidden points of interaction? Instead of being absorbed, can't the electron scatter instead?

In the case of both microstate exploration and decoherence, the precise state changes constantly. An electron on the screen which might forbid an incident electron at time t might not be present at time t'. A particular configuration of scatterers that would destroy the wavefunction at time t might permit it at time t'.

The signature pattern of the double slit experiment is not one event but many thousands. What we see then is not just the value of the probability density of the electron, but also the statistical behaviour of the macroscopic screen. Over a statistical number of events, the pattern must be independent of changes in the precise microstate of the screen. — Kenosha Kid

So let's consider a limiting case where exactly one spot on the screen is available for interaction at any one time - an advance electron hole, as it were. This is what you hypothesize might indeed be the case, right? We can fairly assume that such points are uniformly distributed over the surface of the screen*. If the availability of electron holes imposes an absolute constraint on where an interaction can occur, then instead of the interference pattern we should see just that - a uniform distribution.

* Or in any case, we can't expect their distribution to coincide with the amplitude of the incident wave.

I think it's more economical than parallel universes. — Kenosha Kid

Well, if I understand correctly, the Everett interpretation is characterized more by what it doesn't do - arbitrarily impose a collapse - than by what it does, so in a way it's hard to be more economical than that (although it does ditch those advanced solutions. Hm... could you combine the two?...) But I didn't mean to imply that parsimony and fidelity to the formalism are the only or the most important criteria in evaluating philosophical interpretations. I am rather ambivalent on that point. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionSo I went back to Cramer's papers from 1980s onward in an attempt to gain a better understanding of the transactional interpretation. I think I managed to unconfuse myself a bit regarding the "orthodox" TI, but I am still not sure about your take on it.

The core of the theory is an emission-absorption process, such as when two atoms exchange energy or (as in your presentation) an electron is emitted and later absorbed by a solid. (I think scattering is handled similarly, but I haven't looked into it yet. There is also an issue of weakly-absorbed particles, such as neutrinos, which may not have a future boundary; I know that Cramer has looked into this, but I haven't.)

The process is initiated by a "transaction" between the emitter and the absorber, which is described by the following reversible pseudo-time sequence:

- The emitter produces two half-amplitude waves: a retarded wave going in the forward time direction and an advanced wave going in the backwards time direction (with a negative

energyenergy eigenvalues and phase-shifted by 180 degrees). - The absorber is "stimulated" by the retarded wave from the emitter (offer wave) and also produces a pair of half-amplitude waves going in opposite time directions. The advanced wave from the absorber (confirmation wave) reaches back in time towards the emitter.

- When there are multiple potential absorbers, they all produce confirmation waves with amplitudes proportional to the amplitude of the offer wave. The absorber is selected randomly, with the probability of selection weighted by the square of the amplitude - this is where the Born rule comes into play.

- Once the emitter and the absorber "handshake" (which is sometimes described by another pseudo-process, which I haven't investigated), the "tails" of the wavefunctions going back in time from the emitter and forward in time from the absorber cancel out, as are the imaginary parts of the waves between them, leaving only the superposed real parts of the offer and confirmation waves. To any observer this will look as if a wave traveled from the emitter to the absorber.

(I hope I got this right.)

The above is offered as an interpretation of the standard quantum mechanics formalism, rather than some additional physics. The steps do not describe a causal time sequence of events - they merely serve a pedagogical purpose.

The rationale for the interpretation comes from the fact that, as KK mentioned, some relativistic formulations of the wavefunction equation have two solutions: w and its complex conjugate w*. But complex conjugation is equivalent to time reversal (although it also implies negative frequency, energy and charge) - hence the advanced wave that is produced alongside the retarded wave in TI. Plus the Born rule, etc. - the conjugate of the wavefunction is ubiquitous in the formalism.

It is interesting that both the TI and the Everett MWI start from similar philosophical positions. Both are realist about the wavefunction (in contrast to Copenhagen). Both are offered as minimalistic interpretations that do nothing more than take the math seriously (as Sean Carroll, an Everettian, puts it). "From one point of view, the transactional interpretation is so apparent in the Schrodinger-Dirac form of the quantum-mechanical formalism..., that one might fairly ask why this obvious interpretation of the formalism had not been made previously" (Cramer). But they still end up in very different places. To me it seems like TI goes further out on a limb than MWI. I am uncomfortable about the pseudo-causal narrative of the "transaction." But perhaps the more profound aspects of the interpretation escape me.

This bit I don't understand though:

Because the electron's birth and death are the true boundary conditions of its wavefunction! And here we turn to relativity. The relativistic wavefunction is of the form [E−V]2=[p−A]2+m2. This puts time and space on equal footing (both energy and momentum are squared), requiring knowledge of the particle at two times, not just one. — Kenosha Kid

Whether it's the non-relativistic Schrodinger equation (which has only a retarded solution) or a suitable relativistic equation (which has both), the equation alone does not determine where and how the absorption/measurement will happen - hence the "measurement problem." I am not sure what point is being made here specifically about the relativistic equation.

(The Schrodinger equation can be produced as a non-relativistic limit of a more general relativistic formulation. How then do two solutions reduce to one? Turns out that two versions of the Schrodinger equation are equally valid reductions: the other one has only an advanced solution.)

Now, as for the "not many worlds" interpretation:

There is no guarantee here that this will eventually reduce the number of intersections with the screen to 1. But we are a long way from the original Copenhagen picture of an electron that might be found anywhere. I expect that, if we could solve the many-body Dirac equation for the universe (well, it would have to be some cosmologically-consistent generalisation of it), it probably would resolve to 1 intersection. — Kenosha Kid

I still don't see how this can be. Boundary conditions are, by definition, local. And yet when we do experiments like quantum interference, we find that the measurements depend mainly on the incident wave. Why aren't results confounded by such strong dependence on the boundary conditions? - The emitter produces two half-amplitude waves: a retarded wave going in the forward time direction and an advanced wave going in the backwards time direction (with a negative

-

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionHey, just to let you know, I want to think on this some more, don't want to reply just for the sake of saying something.

-

Midgley vs Dawkins, Nietzsche, Hobbes, Mackie, Rand, Singer...All I can see from your quotes is that Mary Midgley is dissing someone you don't like. If that is what turns you agush... meh. May as well listen to a rap battle or something.

Genes cannot be selfish or unselfish, any more than atoms can be jealous,

elephants abstract or biscuits teleological.

I mean, this is just stupid. I trust there is more to what she says, but you are not selling it well. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

U.S. intelligence agencies warned the White House last year that President Trump’s personal lawyer Rudolph W. Giuliani was the target of an influence operation by Russian intelligence, according to four former officials familiar with the matter.

The warnings were based on multiple sources, including intercepted communications, that showed Giuliani was interacting with people tied to Russian intelligence during a December 2019 trip to Ukraine, where he was gathering information that he thought would expose corrupt acts by former vice president Joe Biden and his son Hunter.

The information that Giuliani sought in Ukraine is similar to what is contained in emails and other correspondence published this week by the New York Post, which the paper said came from the laptop of Hunter Biden and were provided by Giuliani and Stephen K. Bannon, Trump’s former top political adviser at the White House. — WaPo -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionFrom the overlap integral of the retarded wavefunction with the advanced wavefunction:

In transactional QM, this is the very meaning of the Born rule. — Kenosha Kid

But this only gives the "real paths" of the electron once the "boundary condition" on the other end is fixed, i.e. once the measurement already happened at the back screen. This doesn't explain any actual data though: we have no independent knowledge of those "real paths" besides what the interpretation tells us. What we have from experimental setup and observation are just the boundary conditions, the origins of the retarded and the advanced wavefunctions. And while we fix the former by our setup, all we know about the latter in advance is:

When a particle moves from event (r,t) to (r',t'), it still does so by every possible path (Feynman's sum over histories). If you sum up every possible r' at t' and normalise, you recover the wavefunction at t'. — Kenosha Kid

which is no more than what vanilla QM tells us and doesn't explain the really interesting bit, i.e. the measurement problem. And isn't that what we really want from an interpretation?

So what mechanism fixes the forward boundary condition?

Ah, I see. This is deeper than I'd realised. Simply multiply whatever complex number by whatever physical unit: we never see that. I see I have 10 fingers and that I'm 5.917 feet tall, but I have never weighed (12 + 2i) stone. — Kenosha Kid

Well, of course, if you take something that is usually represented by a scalar, such as height or weight, then a real number will be optimal as a mathematical representation. But take something like stress, for example, and you'll want a tensor or a vector at the least. (Although if you really set your mind to it, you can map a quantity of any dimensionality to any other dimension. You can map 6-tuples to scalars and back - it'd just be horribly impractical.)

I'm getting confused now between ontologically real and real as in has no imaginary component. — Kenosha Kid

Yeah, I suspected as much.

The OP holds that the complex wavefunction is an ontic description -- or fair approximation to such -- of how particles propagate through space and time as we represent them. How we describe the relationship between time and space is intrinsically complex, just from straight relativistic vector calculus, which happens to be the language quantum field theory is written in. There are other languages for describing relativity that can do away with the imaginary number and it may well be that in future we can generalise QFT in a similar way; such an endeavour would be part of a general relativistic quantum mechanics. So I don't hold the complex wavefunction to be an ontic description of the particle itself, rather it encodes the ontology of the wavefunction in our spacetime representations accurately, e.g. encodes information vital for doing the physics. — Kenosha Kid

Fair enough. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionAs I read your reply I realized that I didn't really understand the OP :confused: So let me try another question to see if that helps a bit: How does your (transactional?) interpretation recover the Born rule? How do you get the interference stripes in the double slit experiment? Unless I misunderstood again, it seems like you were saying that real-world constraints (availability of holes, etc.) should cut down on indeterminism and perhaps completely eliminate it in the limit. But then we have to believe that these constraints just happen to conspire to produce results consistent with the probability distribution?

But these aren't physical either. It is simply that complex exponentials are much easier to manipulate than individual sines and cosines. — Kenosha Kid

Well, exactly. You can reproduce all complex-valued math without recourse to imaginary numbers or complex exponentials - it would just be more work. But then I don't understand why you insist that

But no complex quantity can be physical in itself, i.e. we can't observe it in nature. — Kenosha Kid

Complex quantities are no more and no less physical than real quantities, tensors, vectors, and whatnot. They are all mathematical objects.

That's actually not an uncontroversial statement. The wavefunction is frequently referred to epistemologically as the total of our knowledge about a system. The OP basically states that it encoded more ignorance than knowledge. — Kenosha Kid

he wavefunction can be written as a real function multiplied by a complex phase defined everywhere (this is trivial: a complex number has magnitude and phase). The phase is important for interference effects, but makes no difference when it comes to observables. The former is why I believe in an ontic wavefunction, and the latter is why the wavefunction might be considered epistemic. — Kenosha Kid

Sorry, you seem to be making a distinction without a difference here. Both the amplitude and the phase are essential for encoding our knowledge about the system. So if that makes the wavefunction real in a broad sense (which is fine by me), then the whole of it has to be real, not just the amplitude. -

Penrose Tiling the Plane.You are overthinking it. I haven't looked at the video, but the wiki on Penrose tiling explains the sense in which the pattern doesn't repeat: it just means that the entire tiling doesn't possess translational symmetry. If you shift it by some amount in some direction, you can never get the same picture - unlike patterns printed on fabrics, wallpapers, etc. The connection with numbers like pi is that those numbers are irrational, which means that their decimal expansion also does not include an infinite periodic part (semi-infinite in this case).

If you can identify a repeating part in a pattern, you can just do sort of a variable substitution, designating that repeating part as one super-tile. Then the entire tiling is simply that one super-tile repeated infinitely in all directions, like squares on a chessboard or hexagons in a honeycomb. With an aperiodic tiling you cannot do that. -

Objective beauty provides evidence towards theism.I hope to provide an argument that utilizes the prime principle of confirmation to show that objective beauty provides evidence in favor of the hypothesis of theism over that of atheism. — Daniel Ramli

Collin's so-called prime principle of confirmation notoriously provides spurious support. Collins tries to repair it with an injunction against ad hoc hypotheses. Whether or not that is a successful strategy for Collin's argument, your argument doesn't even attempt it: your God hypothesis is blatantly ad hoc, i.e. it presupposes everything you need to make your probability as high as you want it to be. -

Determinism, Reversibility, Decoherence and TransactionThat was a nice presentation and an interesting discussion. Thanks for putting in the effort!

I was thinking about what you said about the asymmetry of boundary conditions, e.g.

This does not put time and space on equal footing. The solution requires knowledge of u at one time and two places. These are generally derived from physical considerations, e.g. where the electron wavefunction must vanish: two positions where the wavefunction is zero at one time: generally the start. — Kenosha Kid

[The relativistic wavefunction] puts time and space on equal footing (both energy and momentum are squared), requiring knowledge of the particle at two times, not just one. This is why in relativistic quantum theories, we do not proceed by specifying an initial state, time-evolving it forward, and asking the probability of spontaneously collapsing to a particular final state. Rather, we have to specify the initial and final states first, then ask what the probability is. — Kenosha Kid

The true boundary conditions — Kenosha Kid

Mathematically, of course, any consistent set of boundary conditions is on equal footing with any other. And in any case, rather than solving a boundary value problem by time-evolving a wavefunction (forward and/or backwards), we can equivalently solve a least action problem, which obviates the question of where to start and where to end, since we are doing it everywhere at once. Which makes me wonder about the physical significance of all this, and particularly your main take-away about determinism.

The "trick" of putting some of the boundary conditions ahead in time makes the point a rather trivial one. Another way to state it would be to note that if there is a fact of the matter about the way the world is going to be at some future time, then there is nothing indeterminate about it. Well, of course.

I am also going to take a little issue with this:

This idea of the absolute square is important. It is how we get from the non-physical wavefunction to a real thing, even as abstract as probability. Why is the wavefunction non-physical? Because it has real and imaginary components: u = Re{u} + i*Im{u}, and nothing observed in nature has this feature. The absolute square of the wavefunction is real, and is obtained by multiplying the wavefunction by its complex conjugate u* = Re{u} - i*Im{u} (note the minus sign). Remembering that i*i = -1, you can see for yourself this is real. We'll come back to this. — Kenosha Kid

I wouldn't agree with the statement that the wavefunction is non-physical because it has a complex component. We can represent uncontroversially real entities with complex functions, as you are no doubt aware (e.g. the electromagnetic field in classical electrodynamics, and generally any 2D model where complex representation is expedient). Perhaps your thinking here is prompted by the QM formalism of observables - linear operators that, when applied to the wavefunction, produce real values that correspond to measurements (of position, momentum, and other attributes of a quantum state). But if only measurements are real, then nothing about the wavefunction as such is real, not even its absolute square: a probability density is not a measurement.

Anyway, this is probably a diversion (or not - you tell me). I myself don't regard the question of what there is as important. I take a theory as a whole, with all its ontological furniture, as real (enough) to the extent that it does a good (enough) job. -

On Learning That You Were Wrong and Almost Believing ItWe get attached to our beliefs - that's the main reason we hang on to them in the first place, regardless of their epistemic virtues or lack thereof. We rarely question what we are long used to hold true, and when we do for the sake of form, we rarely admit actual doubt into our hearts. Still, our noetic structures are not impregnable fortresses, and every once in a while a secure belief begins to crumble. But it won't go easily. Unlike logical systems, our minds are not so brittle - they can tolerate some amount of inconsistency.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The latest Times investigation into the president’s tax data and other records found that more than 200 companies, special-interest groups and foreign governments had patronized Mr. Trump’s properties, funneling in millions of dollars, while reaping benefits from him and his administration.

“As president, Mr. Trump built a system of direct presidential influence-peddling unrivaled in modern American politics,” writes an investigative team that has been covering the president’s finances and taxes for almost four years. — New York Times

Key Findings -

Is there a quantum dimension all around us where we can't measure matter?Orbitals are distributions, charge density clouds. They are smeared across the entire universe, but their density peaks in the vicinity of the nucleus, and away from its maxima it rapidly decays to almost nothing.

In any case, this doesn't say anything about measurement. -

Stove's Gem and Free WillI've not heard of this, do you have any names or reading to suggest? — Isaac

Here is one representative (I think - I am no kind of expert) example, with some thoughts on x-phi: Joshua Shepherd, The Folk Psychological Roots of Free Will (2017). This paper has a larger survey of recent experimental work: Esthelle Ewusi-Boisvert, Eric Racine, A Critical Review of Methodologies and Results in Recent Research on Belief in Free Will (2018). -

Stove's Gem and Free WillIn retrospect, I think you are right that determinism is neither here nor there in the issue of moral responsibility and free will. — Olivier5

It is relevant to the extent that the starting point for Strawson's thesis is the old debate on the compatibility of personal responsibility/free will with determinism. But he argues that indeterminism is no better than determinism in this respect. He is looking for "ultimate" responsibility in a reductive sense; with this framing a person can never be "ultimately" responsible, because the buck will always pass to something else (because he already prejudged that it should!) - whether it is a prior state of the universe + deterministic dynamics or chance events.

Responding in the thread while claiming not to be involved is a performative contradiction :razz: You have no obligation to respond just because you are mentioned, but there's no need to be rude. -

Stove's Gem and Free WillIndeed, and 'complicated' is certainly right, but is it that you think such a notion of free-choice need be abandoned for that reason? Or are you more in favour of rolling up one's sleeves and getting stuck in nonetheless? — Isaac

It depends on what one expects the result of such an inquiry to look like. Moral philosophers traditionally tend to look for simple, universal principles in a theory, modeling it, more-or-less, on fundamental physics. I am skeptical that such simple, exceptionless organizing principles could underlie most humanistic notions, such as responsibility or freedom, so to me the more obvious approach would be more in the line of stamp collecting than grand theorizing. This approach is characteristic of the relatively new field of experimental philosophy ("x-phi"), which uses the methods of sociology and experimental psychology to study "free will" and such as aspects of human attitudes and behavior, and then offers modest generalizations that do not go too far beyond the available evidence.

I'm sometimes required to help plead for judicial leniency on the grounds of a person's upbringing or environment. The basis for such action is that somewhere in this muddle we (those involved at the time) can agree that such influences were outside of the person's preferred choices. — Isaac

Oh, interesting. Yes, that's just the sort of example that I had in mind (and how such attitudes can vary, change, be contested, etc.) -

How to improve (online) discourse - a 10 minutes guide by HirnstoffI was going to respond, but I see that this thread has since been taken over by an argument that spilled over from elsewhere. An object lesson of a failure of online discourse, I suppose.

-

How to improve (online) discourse - a 10 minutes guide by HirnstoffThis guy already joined this forum and posted his video a little while back. But I agree, such appeals are pointless and have never had any actual impact.

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillI wasn't so much complaining about a derail. It just seems that you (or maybe just Olivier) are itching to have this discussion - so why not have a dedicated topic for it? That would invite wider participation.

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillCan one of you guys start a thread on determinism/indeterminism, instead of hijacking other threads? (I have the damnedest time making OPs, but I might contribute if there is one.)

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillWhat intrigues me is the expression "what we've been talking about all this time is not what we thought it was". I'm afraid I can't quite make sense of this. A word has to mean what we (community of language users) think it means doesn't it? Could you perhaps rephrase? — Isaac

I was thinking of folk theories, as in folk physics or folk theory of mind - intuitive or conditioned but unschooled understanding of how some aspect of the world works. Such folk theories have a deeper purchase on how we think and interact than just language (if indeed language is just language). And a name like free will can stand in for such a folk theory.

That's not to say that folk theories are inherently deficient. For example, when it comes to moral responsibility (and, to an extent, free will, although as I noted, here things are more muddled), my position is that a "folk theory" is all there is to it. It is just what we personally and popularly believe it is - there isn't anything deeper or truer than that. (Sure, we could look into psychological, sociological, evolutionary, etc. explanations, but those would be explanations of how we historically came to have these particular beliefs about moral responsibility, rather than a better understanding of what moral responsibility really is or should be.)

But for other things - physics, mind - we can indeed gain a better understanding than what we can learn by consulting our intuitions or popular beliefs.

What really matters morally is the difference between having one's actions driven by desires an thoughts one considers one's own, and having one's hand forced by the unwanted desires of others, or desires and thoughts one does not consider one's own (psycho-pathology). All of this can be dealt with without having to send a single electron through any slits! We just don't need to know, in most cases, anything about ultimate cause, we only need go a few steps back and see if such causes are still within or outside of what we consider ourselves. — Isaac

This is where things get complicated. What we hold an individual to be accountable for vs. what we consider to be an external cause can vary quite a bit. Strawson stakes out an extreme position where everything is caused externally, deprecating personal responsibility. No one (outside of philosophy) actually does that, of course, but there is still a lot of variability and inconsistency here. Answers can vary by culture, by individual, and even by how the question is asked or primed. For example, how much does one's upbringing matter? Life experiences? Genetics? Family, nation, race? Do you leave them outside the personal boundary as external causes/influences or not? -

If there is a Truth, it is objective and completely free from opinionYou could just put a link to your blog in your profile, as others do, instead of billboarding it on your user name.

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillYeah, I can't really stand "...therefore X doesn't exist" conclusions (where X is some common feature of our language). I think, 'well what on earth have we all been talking about all this time then?'. — Isaac

Sometimes you may want to conclude that what we've been talking about all this time is not what we thought it was, or that it's just not a well-formed concept, and we may be better off leaving it alone than trying to precisify it with philosophy. I've been drifting towards such a conclusion with respect to free will, especially after looking at some sociological research.

My previous position was to treat free will as something that is real, insofar as people treat it as real: they refer to it, they evaluate their and other people's behavior based on whether they think they exercised their free will. They even appeal to it in a court of law. But it seems that, going by the actual use, the concept of free will is heterogeneous and inconsistent. More importantly, those aspects of free will that matter to us - responsibility being foremost - can be dealt with on their own, with no reference to free will. That is, if you want to consider whether we are morally responsible in such and such circumstances (e.g. when our actions are physically determined by an earlier state of the universe), why not just talk about that? Why confuse matters by bringing up something that no one is quite sure about?

It should be said that in The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility paper and some other related works Strawson does specifically talk about moral responsibility, rather than free will. And he starts his entry on Free Will in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy with these words:

‘Free will’ is the conventional name of a topic that is best discussed without reference to the will. It is a topic in metaphysics and ethics as much as in the philosophy of mind. Its central questions are ‘What is it to act (or choose) freely?’, and ‘What is it to be morally responsible for one’s actions (or choices)?’ These two questions are closely connected, for it seems clear that freedom of action is a necessary condition of moral responsibility, even if it is not sufficient. — Strawson, RET

In the rest of the article he mainly talks about the second question, i.e. the question of moral responsibility. -

Compatibilism Misunderstands both Free Will and Causality.Where is the university? All you've shown me are buildings and grounds and students and faculty and books and equipment. Where in all of that is the university you promised to show me? — Pfhorrest

This went right over his head, I am afraid. -

Compatibilism Misunderstands both Free Will and Causality.LOL Radin. I knew that he was a crackpot, but that was more from the way reasoned more than anything else. Makes sense though.

-

Newton's InconsistencyIt's a common knowledge that Newton's predominant interests throughout his life (judging by the expenditure of time and ink) were esoteric religious studies and alchemy, and that he was a rare jerk.

If that's your trump card in support of your confused OP, I think you should quit while you're ahead. -

Compatibilism Misunderstands both Free Will and Causality.Another apriorist giving this dead horse yet another beating.

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum