Comments

-

Differences that make no difference(sorry for my absence; the thread was intended for general discussion in any case)

There are a few kinds of propositions.

p = all swans are white

might once have been thought true, until black swans were found. Known evidence was consistent with p, yet anyone might have claimed ¬p without deriving a contradiction. p at least seemed truth-apt, however useless the claim may seem.

Sagan's garage dragon is another kind of claim, or at least further evidence-immune. It seems impossible to differentiate whether the existential claim is true or false. Perhaps it's possible to discover a means by which to find the dragon, or lure it to make it's presence known? :) (Neutrinos, first found in 1955 by Cowan and Reines, can be rather difficult to deal with.)

p = there's an invisible spirit/ghost that keeps an eye on you at all times

could be further along this path. Can't think of any evidence that specifically differentiates p and ¬p.

I guess there's broad agreement that solipsism isn't particularly dis/provable (in a purely deductive sense). Or take whatever other incompatible -isms you fancy, doesn't matter in this context.

It's trivial to immunize claims (as alluded to by Sagan). At what point do such claims become differences that make no difference (if they do)? -

Order from ChaosSo, at large, there's energy dispersion in the universe towards heat death (an equilibrium in an expanding universe), countered temporarily in some locales due to blazing suns that radiate energy (cf the fluctuation theorem), energy that can be temporarily accumulated (locally) due to photosynthesis. Great conditions to get some biological evolution going (while it lasts anyway). (Y)

But, when we look close enough, we find both chaos and order, and whatever in between, in the universe. Universality is a great example of a kind of emergence, with no particular intervention or guidance as such.

Still, we're not nature-omniscient. Atoms, for example, are not idealized bouncing billiard balls. We don't know atoms or whatever exhaustively.

Teleological evolution seems a bit like predestination (though more than 99% of all species ever having walked the Earth are now extinct). I find it oddly self-elevating to think of (what we know of as) life, or consciousness (as we know it) perhaps, as some sort epitome or pedestal of what might come about naturally in the universe. Why...? -

Order from ChaosIt seems there may be a sharpshooter or two among us here.

If we suppose all kinds of monkeys typed away at random for who knows how long, then they might produce Much Ado About Nothing after a good long while (21157 words). They might equally produce all the same letters and punctuation in some other order, rendering gibberish in English, or maybe even something syntactically correct in some other language. And they might produce whatever other poetry or nonsense or a scientific masterpiece for that matter.

Yet, beforehand, each of all those productions had equal probability of being produced by the monkeys. It just so happens that we like Shakespeare (well, some do), and so we attribute some special significance to that particular production (which presently has a probability of 100% of existing). Of course Shakespeare wrote in a more specific context than our hypothetical monkeys. It's easy enough to find nonsense produced by humans as well.

If you had a 1000 monkeys, and typewriters, I think you would get a whole lot of broken typewriters with shit on them — Wayfarer

:D Comment made my day. -

This Debunks Cartesian DualismThe holographic principle have been hijacked by some folks out there. :-}

- Quantum woo (RationalWiki article)

- You Aren't Living in a Hologram, Even if You Wish You Were (Ryan F Mandelbaum; Gizmodo; Jan 2017)

-

This Debunks Cartesian DualismI had to look that one up. Learned something new today. (Y)

lead someone down the garden path = mislead, deceive, hoodwink, or seduce

Source: Wiktionary

lead sb up the garden path = to deceive someone

Source: Cambridge Dictionary -

This Debunks Cartesian Dualism

-

This Debunks Cartesian Dualism, let me rephrase that: don't expect @Wayfarer to apologize for Donald Trump's bruise the next day, if he slapped him in a dream. ;)

-

This Debunks Cartesian Dualism, don't expect me to apologize for your bruise the next day, if I slapped you in a dream. :D

-

This Debunks Cartesian DualismDoesn't the atheistic monist have to deal with the same question of when consciousness (i.e. that something extra) begins and ends during a life cycle? — Hanover

I'm thinking everyone does (a/theist mon/dualist)... I don't think anyone have a really comprehensive understanding of mind (per se). That said, there are simple characteristics we do know.

Some emerging research:

- Mind-reading program translates brain activity into words (Ian Sample; The Guardian; Jan 2012)

- Scientists Use Brain Waves To Eavesdrop On What We Hear (Peter Murray; Singularity Hub; from the Public Library of Science (PLoS) Biology; Feb 2012)

- Neural Decoding of Visual Imagery During Sleep (Horikawa, Tamaki, Miyawaki, Kamitani; Science AAAS; Apr 2013)

- Researcher controls colleague’s motions in 1st human brain-to-brain interface (Rajesh Rao, Andrea Stocco; University of Washington; Aug 2013)

- Brain decoding: Reading minds (Kerri Smith; Nature; Oct 2013)

- Mind-Reading Computer Instantly Decodes People's Thoughts (Tia Ghose; LiveScience; Jan 2016)

-

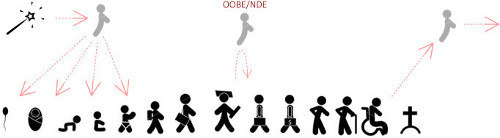

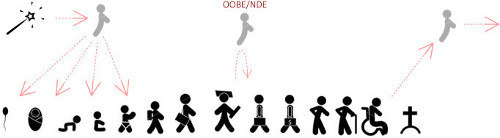

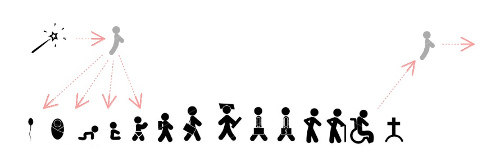

This Debunks Cartesian DualismHey, a truly humorous depiction of an entire philosophical stance. Nice! — javra

Probably the wand that gives it a humorous flair. :)

There are any number of oddities though.

When is this extra stuff installed?

What difference does it make?

What the heck is this extra stuff anyway?

Did Neanderthals have it? Homo erectus? Homo ergaster? Bats? -

This Debunks Cartesian Dualismthere are literally millions of consistent reports of people having experienced out-of-body experiences that can be objectively verified — Sam26

A wee tiny detour?

You don't find it the slightest suspicious that out of body / near death experiences somehow report seeing something, even though their eyes were safely back in their body...?

Alien abduction stories at least report seeing with their eyes.

We tend to explain phantom pain, synesthesia and confabulation a bit more down-to-Earth, for example. -

Idealism pollThe PhilPapers Surveys turned out rather differently:

External world: idealism, skepticism, or non-skeptical realism? non-skeptical realism · 82% (760/931) other ················· 9% (86/931) skepticism ············ 5% (45/931) idealism ·············· 4% (40/931)

What gives? -

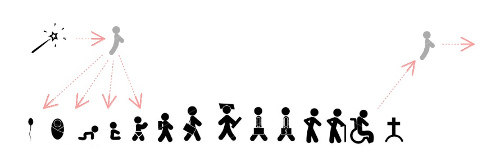

This Debunks Cartesian DualismSeems that religious substance dualism adds something extra, something entirely independent, to our lives:

Can this sort of thing be justified? -

Idealism pollA trap, ?

There's no objection to there being a perceiver, just that the perceived is the perception.

Or, put differently, that the experienced is always the experience.

Or, that everything (literally) is mind stuff, where mind is the likes of experiences, qualia, thinking, love/feelings, headaches, self-awareness, consciousness.

Seems that, in an ontological sense, an experience is part of the experiencer when occurring.

The experienced, on the other hand, may or may not be. -

Idealism poll@Wayfarer, so the Moon and I exists independently of your perception thereof?

- the perception is not always the perceived (Searle and others)

- my experience of you is not you (non-solipsism)

- the experience is not always the experienced (non-idealism)

-

The Survival of the Fittest Model is Not the Fittest Model of EvolutionNatural selection is just a nice story, without a shred of evidence, that appeals to those seeking fitter and not fitter. — Rich

Really?

Would you like to pitch biological evolution (roughly as currently understood) against creationism over in the science (or religion) department?

I'll open a new post referring to your claim, if asked, and if you promise to show evolution the door (or justify your claim I mean). Might include a poll.

Per se, abiogenesis is a hypothesis, and evolution is established. -

The pros and cons of president TrumpIn fact, I did call the police one time when I got my place attacked in the UK and guess what - they came in 2 days, and ended up doing almost nothing, just saying how sorry they were... I think the state bureaucracy is actually really bad and crippling many of these services. For example, I remember healthcare used to be quite horrible in the UK (massive waiting times) - although it was free. — Agustino

You know, I've noticed something vaguely analogous in big business. Monetary resources go up and down, left and right, and can depend on who-knows-what. North Korea testing nukes and missiles is just one example, with an odd ripple effects. When monetary resources go down, some managers tend to leave (you know, the grass always seem greener on the other side), and people on the floor are let go with no backfills, etc. However, when that happens, the work load does not change (at least not proportionally), meaning that existing employees suddenly have more to do. Eventually some things may get dropped as a result, with lots of resistance, complaints, all that. :)

An analogy in society could be cutting down resources for police, or any supporting public/governmental areas, or something subsequently requiring more police resources. Tax cuts tend to mean something gets dropped, and it may not be readily clear what implications there are. Personally, I pay for civilization with taxes (to paraphrase someone I don't recall), and I certainly don't mind doing so. Do we need 3 cars? No, we have 1, and public transportation is fine. In the US it seems an election could be won by promising tax cuts, and meanwhile there are plenty kids on street living in poverty. That's kids for crying out loud. Kids that could end up taking up police resources for that matter. It's ridiculous.

I don't think it's a secret that cooperation, a civilized society, can accomplish a lot more than some scattered (para-anarchistic?) locals. No, government isn't some abstract "evil entity" "over there"; it's a serving body of it's society. -

Existence is not a predicate, well, when I was in the US, I wanted to shake Superman's hand for a job well done and all that, but came up empty handed.

The good folks at the comic con told me my best bet is getting written into a comic book, and that's it.

How disappointing. :)

, I'd say we auto-presuppose that anything that exists is self-identical.

We sort of have to; trying the contrary leads no where.

-

Existence is not a predicate[...] is confusing for everyone. — Srap Tasmaner

Hm. Seems reasonably clear to me.

For something to be real, it have to exist.

For something to exist, it doesn't have to be real. Like Superman or other imaginary things.

Do you have a simpler understanding or use of the words? -

Existence is not a predicateFictional things don't exist, but fictions do. — unenlightened

That's roughly along the lines of how I use the words.

Say, Superman exists, but just isn't real.

But, exists is not a primary predicate. — Owen

Right.

(Y) I'll go with that.

In brief, something like:

- existence is not a logical predicate (∃ is not just another φ)

- existence can be used as a linguistic predicate

-

Post truthLet's be clear that "My freedom ends at the tip of your nose" is an injunction, not an observation. — Banno

Also nicely expressed by The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789:

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the enjoyment of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law. -

Post truthAnd I'm sorry to say, but I think JornDoe has you pretty well nailed. It's only that I do detect an element of actual philosophical insight, that causes me to bother persisting with you. — Wayfarer

My spider-sense gave me the impression of an "any means to my end" sentiment. Agustino would possibly go for some specific theocracy over democracy. -

Post truth:D @Agustino, for some reason I picture you as some combination of opportunist, evolution-denier, anti-vaxxer, geocentrist, young Earth creationist, flat Earth'er, Moon-landing-denier, conspiracy theorist, proud supernaturalist, wannabe rebel, arrogant troll, misogynist, non-empathetic mental barbarian, with imaginary friends in higher places.

-

Towards the Epicurean trilemma@Michael, deductively alone? No, it's:

• limited option: there is unwarranted suffering — evident (Y)

• comprehensive option: all suffering is warranted — justified? justifiable? (N)

But of course it can easily get more complicated. According to some there is indeed such a heaven, except it extends to humans only, well, and if that's Jesus' hangout, then he supposedly suffered, or so their story goes, ... And some always want to get into the semantics, sometimes warranted means deserved, sometimes unwarranted means useless or just preventable, ...

suffering ... is ... just a fact of life — Michael Ossipoff

(Y) Could perhaps even be accounted for in terms of biological evolution. Maybe the rest is overthinking it, or a kind of reification.

Anyway, tossing 1 out renders the remainder a different inquiry altogether. No given warrant of any kind, just what's found by (empathetic) humans. -

Towards the Epicurean trilemmaHow does 6 follow from 2, 3, and 5? — Michael

Observation tells us what's already considered unwarranted suffering. Don't think you'll find many doctors claiming that "the child missing out and suffering due to cancer" is warranted, or that all suffering is warranted. What's considered warranted suffering could, for example, be a kid having uncomfortable dental work done. Is it justifiable that all suffering is warranted? -

Towards the Epicurean trilemmaWhat is "heaven"? Or do you mean that heaven is equivalent to freedom from suffering? — Cavacava

In this context, heaven could be anything free of suffering.

Of course there's an implicit assumption that such a heaven exists, which (to me) seems like the weakest part of the argument. -

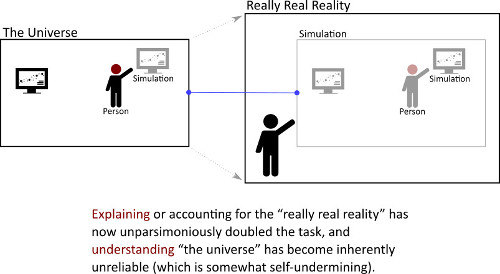

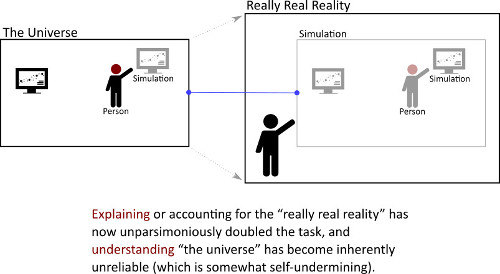

What makes an infinite regress vicious or benign?One variety of vicious infinite regress could be when trying to justify some proposition, p, and justifying p is done with (or requires) a different proposition, p1, which, in turn, depends on p2, ..., ad infinitum, where pn diverges.

Divergence could, for example, mean never approaching anything in particular (which also has a specific technical meaning in mathematics).

If explaining a claim is deferred to explaining a larger claim, which, in turn, is deferred to explaining an even larger claim, ad infinitum, then you've likely hit a vicious infinite regress, i.e. a non-explanation to begin with.

On the other hand, if all propositions/claims can be shown to collapse into one (like pn+1 = pn), for example, then it's not a vicious infinite regress. -

The Cartesian ProblemThe body runs itself. — Michael Ossipoff

Sure. Consciousness occurring is a kind of "running", to use your terminology. If you're out, unconscious, have been put under by anesthetic or whatever, then that kind of "running" isn't occurring. You may come to, though, as long as the body has retained sufficient (structural) integrity.

The separate “consciousness” is Spiritualist fiction. — Michael Ossipoff

I don't think my take presumed or implied anything supernatural or spiritual in particular. At least I don't think there's any requirement to invoke such things, even though we don't self-comprehend exhaustively. -

Question for non-theists: What grounds your morality?rational autonomy — Brian A

(Y)

We generally like freedom and dislike harm (including other animals), and that can, and do, inform judging actions in terms of morality.

Which hardly are matters of arbitrary, ad hoc opinion, not mere whims of the moment; who ever called liking freedom or disliking harm random or discretionary anyway?

If you require myths and commands to understand that, then there's a good chance you're a bit scary. :)

The objective versus subjective thing is misleading from the get-go. -

The Cartesian ProblemNo, that's Dualism. — Michael Ossipoff

Not substance dualism, though. Unless you think of space/objects and time/processes as substances? I just think of them as different aspects of the same world, perhaps like memories, inertia, gravity, what-have-you, are aspects of the world that we can differentiate, but not in an incommensurate fashion. The rock in the driveway isn't conscious. My neighbor is (for the most part, at least when I run into them). -

Omniscience is impossible, you found us! Welcome to. And what the heck took you so long? :)

-

The Cartesian ProblemAs I was saying before, you're using Dualism with a different meaning. You're using it to mean the absence of one-ness with our surroundings.

...whereas the academic Western Dualists use "Dualism" to mean a dissection of the person (the animal) into body and Mind, two distinct substances or entities. ...a belief in Mind as something separate from the body. — Michael Ossipoff

Sorry, my bad for being unclear, I didn't mean to describe old-school substance dualism à la Descartes — supposedly independent, real "substances" — res cogitans (thinking substance, mental) versus res extensa (extended substance, material).

Rather, I meant to account for the apparent dualism monistically, e.g. self versus other, as simply being due to (self)identity, while still taking Levine's explanatory gap serious.

All the self stuff together already is what our cognition is — our self-awareness, 1st person experiences, thinking, etc (when occurring) — and is ontologically bound by (self)identity, which sets out mentioned partitioning. We're still integral parts of the world like whatever else, interacting, changing, albeit also individuated.

So, cutting more or less everything up into fluffy mental stuff and other material stuff is misleading from the get-go; monism of some sort is just fine, and perhaps a better categorization is that mind is something body can do, and body is moved by mind, alike, which (in synthesis) is what we are as individuals. Whatever it all is. -

Cosmological Arg.: Infinite Causal Chain Impossible@noAxioms, you're right, I was thinking more generally in terms of those uhm "larger-world" hypotheses. Something like ...

- modal realism (possible worlds)

- many worlds (quantum mechanics)

- multiverse (e.g. ensemble, M-theory, brane collisions)

-

The Cartesian ProblemBut I’m not mixing separate things. I’m just not unnecessarily separating, dissecting, the animal (including us humans) into artificially separate body and Consciousness. — Michael Ossipoff

That was the point (sort of). :)

What choice do we have but the usual local 1st person perspective? There's no self-escape, no becoming whatever else. We're already, always bound by identity, which sets the stage for "dualistic" (or "partitioned") thinking, like this one:

- self: mind, consciousness, self-awareness, feelings, map-making, ...

- other: the perceived, the modeled, the encountered, the territories, ...

Hence Levine's explanatory gap. The troubles begin when taking this to mean substance dualism:

Watch. I decide consciously to raise my arm, and the damn thing goes up. (Laughter) Furthermore, notice this: We do not say, "Well, it's a bit like the weather in Geneva. Some days it goes up and some days it doesn't go up." No. It goes up whenever I damn well want it to. — Searle- Source: Our shared condition — consciousness, John Searle, TEDxCERN

-

Cosmological Arg.: Infinite Causal Chain ImpossibleHow is this hypothesis backed up? Because if the other universes are undetectable, then I am guessing that it was not brought up from empirical data. Then was it deduced somehow? — Samuel Lacrampe

It apparently fell out of some interpretations of quantum mechanics, and later some string theories.

Quantum mechanics is well-established, string theories aren't. -

The Cartesian ProblemOur thinking is already "dualistic", as expressed ontologically by all things being just themselves, and not anything else, including our (individuated) selves versus whatever else.

As mentioned by , there's nothing contradictory in that, except when messing up anything with anything else, self with other, ...

Maybe "'partitioning' thinking" is better wording, e.g. self-awareness versus not-self/other.

We're still part of the same world, along with whatever else, though. -

Is Atheism Merely Disbelief?Bare-bones definitions could be something like:

- atheism is absence of theism, or disbelief therein, hence the leading 'a'

- an atheist is a human that can be characterized by atheism

Of course most or all humans harbor beliefs of whatever kind.

In the case of atheists, I guess that could then be anything but theism.

I just tend to get a bit suspicious when discussions like this come up, because often enough they're attempts to shift the burden of proof.

jorndoe

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum