Comments

-

Cosmos Created MindIf you have any comment on this brief passage I included from Kant, then I will discuss it. Other than that I have no further comment at this point.

If we take away the subject or even only the subjective constitution of the senses in general, then not only the nature and relations of objects in space and time, but even space and time themselves would disappear, and as appearances they cannot exist in themselves, but only in us — Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, B Edition, B59

I’m not trying to be uncharitable but your responses while intelligent and well articulated show some pre-commitments that need to be made explicit. -

The Mind-Created WorldThe question would be "persuasive to whom?". — Janus

Hopefully to the person one is trying to persuade. But relativism does seem impossible to avoid. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt's not a matter of strictly rational, i.e. non-empirical, theories being true or false, but of their being able to be demonstrated to be true or false. — Janus

The only way the veracity of philosophical arguments is demonstrable is through their logical consistency and their ability to persuade. But they can't necessarily be adjuticated empirically. Case in point is 'interpretations of quantum physics'. They are not able to be settled with reference to the empirical facts of the matter. -

The Mind-Created WorldBut doesn't it apply to any attempt at an objective viewpoint, not to viewing consciousness especially? — J

Notice that Adam Frank specifcally refers to broad philosophical questions: 'there is a whole class of problems that are at the very root of some of our deepest questions, like the nature of consciousness, the nature of time, and the nature of the universe as a whole.' My reading is that in all these cases, we're thinking about something that can't be treated in an objective manner, because we're not outside or apart from what we're thinking about.

We are outside of or apart from the subjects of the natural sciences. As Frank says, 'billiard balls' - and a whole bunch more, up to and including space telescopes - all of these are matters of objective fact. Less so for the social sciences and psycbolpgy. Perhaps not at all for philosophy.

The phenomenology I'm reading is very much concerned with this, but reference to it is hardly found in English-language philosophy. -

Cosmos Created MindI think in a sense there is a kind of category error in your arguments in that keep framing them against the wrong target — Apustimelogist

It's also possible you don't see the target. -

BanningsThat poster said a few weeks ago s/he wanted to be banned for some reason, but then kept posting. My impression was that s/he was a thoughtful contributor, but not very well-versed. Maybe wrestling with some existential angst, which online philosophy isn't necessarily going to be a cure for.

-

The Mind-Created WorldIt makes intuitive sense to me, but it is (at this stage at least) obviously not a falsifiable theory of the human mind, and even if it were it still wouldn't answer the deepest questions about the relationship between the mind and the brain. — Janus

The point of falsifiability is not that it's the gold standard for all true theories. The point is only that it allows for the distinction between genuine empirical theory and pseudo-theories. The original examples that Popper gave were Marxism and Freudianism - very influential in his day and often regarded as scientific — when, he said, they could accomodate any new facts that came along. But conversely, that doesn't mean that rationalist philosophy of mind can't be true, because it is not empirically falsifiable. That is to regard empiricism as the sole criterion of validity, which wasn't how the distinction was intended by Popper.

I've noticed and read about McGilchrist but haven't taken the plunge - too many books! But I'm totally sympathetic to what I take to be his orientation. -

The Mind-Created WorldThis is from Adam Frank, one of the co-authors of The Blind Spot of Science (alongside Marcello Gleiser and Evan Thompson.) Frank is a professor of astrophysics at Rochester University. But he's also a longtime Zen practitioner, and in this excerpt, he talks about the strengths and weaknesses of the ideal of objectivity in philosophy and science. My bolds.

The verb “to be” is something that science doesn’t really know how to deal with. What has happened is that scientists have often ignored it and tried to pretend that it doesn’t exist. They’ve sort of defined it away, and that’s actually fine for some problems—doing that has actually allowed science to make a whole lot of progress. For instance, if you’re just talking about balls on a pool table, fine: you can totally get the Observer out of it. But there is a whole class of problems that are at the very root of some of our deepest questions, like the nature of consciousness, the nature of time, and the nature of the universe as a whole, where doing that (taking the Observer out) limits you in terms of explanations, and it’s really bound us up in a lot of ways. And it has really important consequences, both for science, our ability to explain things, but also for the culture that emerges out of science.

In order to remove the Observer you have to treat the world as dead, you know? One of the things that for me is really important is to move away from like words like “the Observer” and focus on experience. Because part of the problem with experience is that it’s so close to us that we don’t even see it. And it’s only in contemplative practice that you really have to deal with it. …

Physicists are in love with the idea of objective reality. I like to say that we physicists have a mania for ontology. We want to know what the furniture of the world is, independent of us. And I think that idea really needs to be re-examined, because when you think about objective reality, what are you doing? You’re just imagining yourself looking at the world without actually being there, because it’s impossible to actually imagine a perspectiveless perspective. So all you’ve done is you’ve just substituted God’s perspective, as if you were floating over some planet, disembodied, looking down on it. And, so, what is that? This thing we’re calling objective reality is kind of a meaningless concept because the only way we encounter the world is through our perspective. Having perspectives, having experience: that’s really where we should begin. — Adam Frank, Astrophysicist and Zen Practitioner

-

Cosmos Created Mindmetaphysical naturalism

— Wayfarer

By which you mean exactly what? — 180 Proof

Exactly as defined:

Metaphysical naturalism is a philosophical worldview that holds only natural elements, principles, and forces exist, and the supernatural does not. It is an ontological claim about the composition of reality, asserting that the universe is a unified whole that can be explained by natural laws and processes, such as those studied by science. This perspective excludes the possibility of deities, spirits, miracles, or supernatural intervention.

Einsten's question was unwarranted. — AmadeusD

Who are you to say? Einstein's question was 'does the moon continue to exist when nobody is looking at it?' He had very good reasons to ask that question, which is still highly relevant. That it could have been called into question by physics itself is highly significant.

To focus on one thing: I indeed believe that I am an objective existent- an element of mind-independent actual reality. — Relativist

My response is that you are an “objective existent” only when viewed from a perspective other than the first-person. Your own conscious existence is accessible to you only first-personally, and even then not in the same way you know where your car keys are. To say of yourself “I am objectively existent” is already to adopt a third-person stance toward your own being and then retroject it into the first-person. In other words, you are importing the conditions under which others know you into the conditions under which you exist for yourself—and that distinction is precisely what the claim glosses over.

From the first-person standpoint, one does not encounter oneself as an “object in mind-independent reality” at all, but only as immediate subjective awareness. The moment you describe yourself as an “objective existent,” you have silently shifted to a third-person perspective—precisely the standpoint from which you appear as an object among others.

my position is that ontology can be entertained (and beliefs can be justified) in spite of the phenomenology and logical necessity of a perspective that your essay focuses on. — Relativist

The term “ontology” is important in disciplines like computer science, where it names a formal scheme for classifying components within a system, and in biology, where it underwrites taxonomies of genera and species. But that is not what ontology originally meant in philosophy. As Aristotle makes clear in the Metaphysics, ontology is not the classification of beings within a given framework, but inquiry into being qua being.

So when you say that ontology can be pursued “in spite of” the phenomenological and perspectival conditions my essay focuses on, what you are really doing is presupposing precisely what philosophical ontology is meant to examine: namely, the conditions under which objectivity, mind-independence, and even “being a thing” are first made intelligible to us.

(I’d also add that there is a strong tendency in modern analytic philosophy to deny that there even can be a “first philosophy” in Aristotle’s sense—no inquiry into being qua being, only local ontologies tied to particular sciences or formal frameworks. But that denial is itself a substantive metaphysical commitment, not a neutral methodological choice. Or rather, it often amounts in practice to projecting the methods and representational constraints of the special sciences onto the domain of reality as such—thereby quietly substituting a methodological limitation for an ontological conclusion.)

You literally just referred to the "real world". Further, you acknowledged there is a mind-independent reality in your essay when you said: "there is no need for me to deny that the Universe is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind." — Relativist

You're insisting that you 'understand what I mean' but your remarks tend to undermine that. There are empirical facts, of that I have no doubt. But:

If we take away the subject or even only the subjective constitution of the senses in general, then not only the nature and relations of objects in space and time, but even space and time themselves would disappear, and as appearances they cannot exist in themselves, but only in us — Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, B Edition, B59

At the same time, Kant also acknowledges the role of empirical fact in his reckonings, saying that he is at once an empirical realist and a transcendental idealist (ref.)

It is logically possible that some elements of our mental image of the real world are true- that they correspond to the actual, real world. You don't confront this possibility, but this doesn't stop you from judging that physicalism (which is a world(model)) is false. I do regard this as a flaw in your essay, because you include no reasoning for the judgement. — Relativist

I am not saying that the world is illusory, nor that none of our representations correspond to reality. I do know where my car keys are! My claim is different: that what we call the “objective world” has an ineliminably subjective foundation—that objectivity itself is constituted through perspectival, experiential, and cognitive conditions. In that sense, the world is not “self-existent” in the way naïve realism supposes; it lacks the kind of intrinsic, framework-independent reality we ordinarily project onto it.

This is not a denial of realism in the sense of stable, law-governed regularity, but a rejection of the stronger metaphysical thesis that the world, as described by physics, exists exactly as it is described, wholly independent of the conditions of its intelligibility (i.e. 'metaphysical realism'). And in fact, modern physics—especially quantum theory—has undermined the idea of observer-free, self-standing physical reality. Hence Einstein's question!

You keep pressing me to affirm some alternative “substance” to take the place of the physical—some immaterial stuff, or “mind as substance.” But that is precisely what I am not doing. My critique targets the shared presupposition of both physicalism and substance dualism: that ultimate reality must consist of self-subsisting things. What I am questioning is that very framework, not merely substituting one kind of substance ('mind') for another ('matter'). That is still the shadow of Cartesian dualism. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?Roombas have "drives", to clean. — hypericin

But they don't heal, grow, reproduce, or mutate. Agree that it's very hard to determine what is or isn't sentient at borderline cases such as viruses (presumably not) or jellyfish and so on.

Somewere I once read the aphorism that 'a soul is any being capable of saying "I am"'. i rather liked that expression. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?I would like to think that the sentience of beings other than human is not something for us to decide. Whether viruses or archai or plants are sentient may forever remain moot, but that anything we designate with term 'being' is sentient is a part of the definition (hence the frequent Buddhist reference to 'all sentient beings'.)

-

Cosmos Created MindNo, it's not because of my acceptance of mind-independent objects. It was because of the words you used*. Can you understand why "mind is foundational to the nature of existence" sounds like an ontological claim? This is the root of what I referred to as equivocation. You don't fully cure this with the disclaimer (i.e. the text I underlined in the above quote) because you are discussing "judgements we make about the world" - and here, you appear to be referring to the real world. Then again, maybe you're referring to "judgements we make about the mind-created world(model)". I'm sure you aren't being intentionally equivocal, but your words ARE inherently ambiguous. Own this- they're your ambiguous words! Don't blame the reader for failing to disambiguate the words as you do. Rather, you should refrain from using terms like "world" and "nature of existence" to refer to the content of minds. It's easily fixed, just as I did when revising "mind-created world" to 'mind-created world(model)" — Relativist

You say I should distinguish between "judgements about the world" and "judgements about the mind-created world(model)." But this is precisely the distinction I'm arguing cannot be coherently maintained.

When you speak of "the real world" that my judgements are about, you're already conceptualizing it, referring to it, bringing it within intelligibility. The "real world" you have in mind—the one you want to contrast with my "model"—is itself always already a conception. You cannot step outside all conceptualization to point at what lies beyond and say "that's what I really mean."

This isn't ambiguity on my part. It's the recognition that there is no meaningful way to refer to "the world" apart from how it shows up within some framework of intelligibility. Not because mind creates or invents the world, but because "world," "object," "tree," "exists"—all these terms only have content within a cognitive framework.

You want me to say: "Here's my model, and there's the real world my model is about." But I'm saying: the "real world" in that sentence is still part of your conceptual apparatus. You're not escaping the framework; you're just pretending you have.

So no—I won't adopt your terminology, because it presupposes the very thing at issue: that we can meaningfully refer to a "real world" wholly independent of cognition, and then compare our "models" to it. We cannot. Every comparison is already within cognition.

This incidentally harks back to an earlier discussion about correspondence in respect of truth.

the adherents of correspondence sometimes insist that correspondence shall be its own test. But then the second difficulty arises. If truth does consist in correspondence, no test can be sufficient. For in order to know that experience corresponds to fact, we must be able to get at that fact, unadulterated with idea, and compare the two sides with each other. ...When we try to lay hold of it, what we find in our hands is a judgement which is obviously not itself the indubitable fact we are seeking, and which must be checked by some fact beyond it. To this process there is no end. And even if we did get at the fact directly, rather than through the veil of our ideas, that would be no less fatal to correspondence. This direct seizure of fact presumably gives us truth, but since that truth no longer consists in correspondence of idea with fact, the main theory has been abandoned. In short, if we can know fact only through the medium of our own ideas, the original forever eludes us; if we can get at the facts directly, we have knowledge whose truth is not correspondence. The theory is forced to choose between scepticism and self-contradiction. — Blanshard, Brand - The Nature of Thought,1964, v2, p268

But none of this is an argument that 'we don't know anything about the world'. It's an argument to the effect that our knowledge of world has an ineliminably subjective pole which does not show itself amongst the objects of cognition, but inheres in the way that objects are known by us. Again, you think that by saying that, I'm claiming that the world is all in the mind or the content of thought. I'm not claiming that, but I'm saying that positing of anything that exists entirely independently of the mind is mistaken, because our cognitive appropriation of the object is necessary for us to say anything about it.

As noted, understanding necessarily entails perspective, and perspective does not entail falsehood. — Relativist

I didn't say that perspective entails falsehood. I said that perspective is necessary for any proposition about what exists, and that only the mind can provide that perspective. Physicalism wants to assign inherent reality to the objects of cognition, as if they are real apart from and outside any cognition of them. But if they're apart from and outside cognition, then nothing can be said. Objects being independent of individual subjectivity is a methodological practice, but then transposing that to the register of 'what exists' becomes metaphysical naturalism, which is of a piece with physicalism.

I have mentioned I published The Mind Created World on Medium three weeks before ChatGPT went live, in November 2022 (important, in hindsight). A couple of weeks back, I pasted the text into Google Gemini for comment, introducing it as a 'doctrinal statement for a scientifically-informed objective idealism' (hence Gemini's remarks about that point.) You can read the analysis here. I take Google Gemini as an unbiased adjuticator in such matters.

And I do know how non-obvious this idea is, due to the 'naturalism which is the inherent disposition of the intellect' as Bryan Magee puts it in Schopenhauer's Philosophy. He says it is something that can only be ameliorated with a considerable degree of intellectual work, 'something akin to the prolonged meditative practices in Eastern philosophy'.

Lastly, the book I refer to in that OP, is Mind and the Cosmic Order: How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why this Insight Transforms Physics, Charles Pinter. Pinter was a professor of mathematics, all his other books are on that subject (he's since died, he published this book at a very great age. Regrettably, it hasn't received much attention, as he wasn't an insider in the philosophy profession.) But this book is grounded in cognitive science and philosophy, discussing many of the issues we're talking about here. And I don't regard the argument I put forward in Mind Created World as at odds with science in any sense - only with metaphysical naturalism, which is a different matter.

And that really, really is all I have to say for now. I am engaged in other writing projects and need to give them the time and attention they deserve. Thank you once again for your questions and criticisms. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?Upthread somewhere I linked to an Evan Thompson paper 'Could All Life be Sentient'? He says, briefly, that it's an undecideable question, because it's too hard to specify exactly where in the process of evolution sentience begins to emerge. But he says it's an open question, and an important question, one that hasn't been settled. It's also a question in phenomenology of biology, as 'phenomenology' is specifically concerned with the nature of experience from the first-person perspective.

One of the ground-breaking books (which Thompson cites) is Hans Jonas The phenomenon of life: toward a philosophical biology. Dense book, too hard to summarise, but well worth knowing about. One of the gists is that the emergence of organic life is also the emergence of intentional consciousness, even at very rudimentary levels of development. Like, nothing matters to a crystal or a rock formation, but things definitely matter to a bacterium, because it has skin (or a membrane) in the game, so to speak. It has the drive to continue to exist, which is something only living things exhibit. And that it plainly tied to the question of the nature of consciousness (if not rational sentient consciousness of the type humans exhibit.) -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?There's no third person without the first person. Modern science began by the bracketing out of the subject. Another of my potted quotes:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, Pp 35-36 -

Cosmos Created MindI am not positing 'metaphysical beliefs'. I am pointing out the inherent contradiction in the concept of the mind-independent object.

— Wayfarer

You made these assertions that apply to ontology:

1. Mind is foundational to the nature of existence

2. To think about the existence of a particular thing in polar terms — that it either exists or does not exist — is a simplistic view of what existence entails. In reality, the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it."

Both of these pertain to ontology (metaphysics). By stating them, you are expressing something you believe. Hence, they reflect metaphysical beliefs.

There is no "inherent contradiction" in the concept of a "mind independent object", but I think I understand why you say this: "object" is a concept - an invention of the mind. But this overlooks the possibility that there is a real-world referrent for the "objects"; and that there are good reasons to believe this is the case (irrespective of whether you find these to be compelling) — Relativist

The reason I'm not making an ontological statement, is because I've already stated 'Adopting a predominantly perspectival approach, I will concentrate less on arguments about the nature of the constituents of objective reality, and focus instead on understanding the mental processes that shape our judgment of what they comprise.'

You, however, will interpret that as an 'ontological statement' because of your prior acceptance of the reality of mind-independent objects. Mind-independence is your criterion for what must be considered real. That is why I say at the outset that a perspectival shift is required.

I'm not saying that 'objects are an invention of the mind' but that any idea of the existence of the object is already mind-dependent. What they are, outside any cognitive activity or idea about them, is obviously unknown to us. What 'an object' is, outside any recognition of it by us, is obviously not anything. Neither existent, nor non-existent. (That I take as the actual meaning of Kant's 'in-itself' although he spoiled it by calling it a 'thing', as it hasn't even really reached the threshold of any kind of identity.)

But does "nature of existence" refer to the mind-independent (billions of years old) real world that you acknowledge? Whether or not your inclined to talk about it, the real world is something we can talk about, and we can talk about its "nature". That's an integral part of ontology. — Relativist

"though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle."

I accept that, at the outset, as an empirical fact. So I'm not denying it. What physicalism wants to do, though, is to say that the Universe with nobody in it is 'the real universe' (which is the same as 'the unseen object' or the 'mind-independent object'). Physicalism forgets that the mind provides the framework within which any ideas about the universe (or anything whatever) are meaningful.

RevealThe fundamental absurdity of materialism is that it starts from the objective, and takes as the ultimate ground of explanation something objective, whether it be matter in the abstract, simply as it is thought, or after it has taken form, is empirically given—that is to say, is substance, the chemical element with its primary relations. Some such thing it takes, as existing absolutely and in itself, in order that it may evolve organic nature and finally the knowing subject from it, and explain them adequately by means of it; whereas in truth all that is objective is already determined as such in manifold ways by the knowing subject through its forms of knowing, and presupposes them; and consequently it entirely disappears if we think the subject away. Thus materialism is the attempt to explain what is immediately given us by what is given us indirectly. All that is objective, extended, active—that is to say, all that is material—is regarded by materialism as affording so solid a basis for its explanation, that a reduction of everything to this can leave nothing to be desired (especially if in ultimate analysis this reduction should resolve itself into action and reaction). But we have shown that all this is given indirectly and in the highest degree determined, and is therefore merely a relatively present object, for it has passed through the machinery and manufactory of the brain, and has thus come under the forms of space, time and causality, by means of which it is first presented to us as extended in space and ever active in time. From such an indirectly given object, materialism seeks to explain what is immediately given, the idea (in which alone the object that materialism starts with exists), and finally even the will from which all those fundamental forces, that manifest themselves, under the guidance of causes, and therefore according to law, are in truth to be explained. To the assertion that thought is a modification of matter we may always, with equal right, oppose the contrary assertion that all [pg 036]matter is merely the modification of the knowing subject, as its idea. Yet the aim and ideal of all natural science is at bottom a consistent materialism. The recognition here of the obvious impossibility of such a system establishes another truth which will appear in the course of our exposition, the truth that all science properly so called, by which I understand systematic knowledge under the guidance of the principle of sufficient reason, can never reach its final goal, nor give a complete and adequate explanation: for it is not concerned with the inmost nature of the world, it cannot get beyond the idea; indeed, it really teaches nothing more than the relation of one idea to another. — Arthur Schopenhauer, World as Will and Idea

If I challenge you, which tree are you talking about, you will say, 'I don't know, any tree.' But you and I both have ideas of the tree already in mind, which allows us to converse. What is the 'real' tree, outside any conception or experience of it - that is an abstraction which has no meaning. At that point it become an empty word, a stand-in for 'any object'. And the 'billions of years old universe' is reckoned in units which we derive from the annual rotation of the earth around the Sun. When you speak of it, you already have that unit in mind. Remove any idea of perspective or 'years' and then what do you see?

What this whole argument is about is, as Schopenhauer states clearly, is the 'subject who forgets himself'. That is precisely what physicalism does - it 'abstracts away' the subject from the so-called objective measurement of the primary attributes of bodies, and then tries to understand itself as a product of those objective entities that it has abstracted itself away from in the first place. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?I don't see that as different to what I'm saying. So I don't agree that I'm not in agreement. :-)

-

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?And it seems to me that one simple explanation of this is that the notion is incoherent. — Banno

It's incoherent for the exact reason that this thread was created months ago! Even designating 'the quality of lived experience' as 'quale' or 'qualia', automatically transposed the entire discussion to the wrong register. It suggest that there is some such thing or state - which there is not. The quality of experience, 'what it is like to be', is always first-person, prior to any discussion. You will invariably try and drag the discussion in the direction of what can be expressed in terms of symbolic logic, but 'what it is like to be' can't be accomodated within that framework, for the simple reason that it is not objectively real. That is what this whole thread is about. That said, there is no 'hard problem of consciousness' at all. The whole reason for Chalmer's polemic is to show up an inevitable shortcoming of third-person science. Once that is grasped, the 'problem' dissappears. But it seems extraordinarily difficult to do!

Chalmers basically said that there is nothing about physical parameters – the mass, charge, momentum, position, frequency or amplitude of the particles and fields in our brain – from which we can deduce the qualities of subjective experience. They will never tell us what it feels like to have a bellyache, or to fall in love, or to taste a strawberry. The domain of subjective experience and the world described to us by science are fundamentally distinct, because the one is quantitative and the other is qualitative. It was when I read this that I realised that materialism is not only limited – it is incoherent. The ‘hard problem’ of consciousness is not the problem; it is the premise of materialism that is the problem. — Bernardo Kastrup -

The Mind-Created WorldI don't agree that it undermines the idea of self-existing things, meaning things that exist in the absence of percipients. — Janus

That precise point is written all over the history of quantum mechanics. The customary dodge is 'well, there are different interpretations' - but notice this also subjectivises the facts of the matter, makes it a matter of different opinions. If you don't see it, you need to do more reading on it. The fields of quantum physics are in no way 'building blocks', which is a lame attempt to apply a metaphor appropriate to atomism to a completely different conceptual matrix.

The whole debate between Bohr and Einstein, whilst very technical in many respects, is precisely about the question of whether the fundamental objects of physics are mind-independent. This has already been posted more than once in this thread, but it still retains relevance:

From John Wheeler, Law without Law:

The dependence on what is observed upon the choice of experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the view that the universe exists "out there", independent of all acts on observation. In contrast Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it givs us. Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word “phenomenon”. In today's words Bohr’s point – and the central point of quantum theory – can be put into a single, simple sentence. "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed ) phenomenon”.

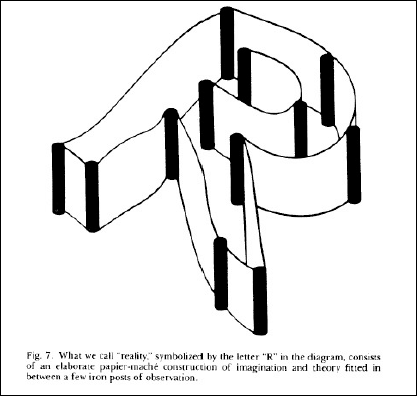

‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

A clear a statement of 'the mind created world', as I intended it, as you're likely to find anywhere. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?But are qualia real without consciousness?

— Wayfarer

Can you set out how this might work? What are you suggesting? — Banno

I'm suggesting that in the context of philosophy, 'qualia' are defined as subjective and first-person in nature. Look it up.

I think an issue with Chalmer's 'Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness' is just that problems are there to be solved, whereas the nature of consciousness (or mind) is a mystery. 'A mystery is a problem that encroaches upon itself because the questioner becomes the object of the question' as Gabriel Marcel put it. It's also not a 'brute fact' - being consciously aware is prior to the knowledge of any facts. Infants are consciously aware, with almost no grasp of facts. -

First vs Third person: Where's the mystery?seeing colours - having qualia - is not constitutive of consciousness. — Banno

But are qualia real without consciousness? Qualia are first person as a matter of definition.

So we agree consciousness is not a thing. But I don't see how calling it a "subjective experience" is at all helpful in explaining what it is. — Banno

Perhaps it is not something that can be, or must be, explained. That's what makes it a hard problem! -

Banning AI AltogetherThis non-paywalled article in Philosophy Now is worth the read in respect of this topic. Presents the 'no' case for 'can computers think?' Rescuing Mind from the Machines, Vincent Carchidi. If if you don't agree with the conclusions, he lays out some of the issues pretty clearly.

-

Cosmos Created MindYou had pointed to your essay after I challenged your justification for your metaphysical beliefs — Relativist

I am not positing 'metaphysical beliefs'. I am pointing out the inherent contradiction in the concept of the mind-independent object. It's actually physicalism that is posing a metaphysical thesis (and a mistaken one.)

As for 'the constituents of objective reality', I said in the essay, I leave that to science, whilst also saying 'I’m well aware that the ultimate nature of these constituents remains an open question in theoretical physics' - which it does.

My challenge to physicalism is that it posits that there are objects that exist independently of any mind or act of observation. Physicalism doesn't just say "physical things exist"—it says they exist as determinate objects with specific properties prior to and independent of any cognitive relation. But "determinate object with specific properties" is already a description that presupposes a framework of conceptual articulation. The physicalist wants to stand outside all frameworks and describe what's there anyway—but that move is incoherent. You cannot meaningfully refer to "the mind-independent object" without already employing the cognitive apparatus you're trying to transcend.

This isn't a rival metaphysical thesis. It's pointing out that the foundational claim of metaphysical realism—that objects exist as determinate things-in-themselves wholly apart from cognition—cannot be coherently formulated.

:ok: -

The Mind-Created WorldI have an essay on it I’m trying to get published. If it is I’ll provide a link if you’re interested.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThe irony enters when those, who generally take science to have only epistemic or epistemological, and not ontological, significance, nonetheless seek to use the results of quantum physics to support ontological claims, such as that consciousness really does, as opposed to merely seems to we observers to, collapse the wave function, and that consciousness or mind is thus ontologically fundamental. — Janus

I’ve been studying Michel Bitbol on philosophy of science, and he sees many of these disputes as arising from a shared presupposition: treating mind and matter as if they were two substances, one of which must be ontologically fundamental. In that sense, dualists and physicalists often share two assumptions—first, that consciousness is either a thing or a property of a thing; and second, that physical systems exist in their own right, independently of how they appear to us.

On Bitbol’s reading, quantum theory supports neither position. It doesn’t establish the ontological primacy of consciousness conceived as a substance—but it also undermines the idea of self-subsisting physical “things” with inherent identity and persistence. What it destabilises is the very framework in which “mind” and “matter” appear as separable ontological kinds in the first place.

Because both dualism and materialism tacitly treat consciousness as something—a thing among other things—while also presuming that physical systems exist independently of observation, the observer problem then appears as a paradox. The realist question becomes: what are these objects really in themselves, prior to or apart from any observation?

This line of thought aligns closely with what has humorously been called Bitbol’s “Kantum physics”—a deliberate play on words marking the Kantian dimension of quantum theory. Just as Kant argued that we know only phenomena structured by our cognitive faculties, Bitbol argues that quantum mechanics describes the structure of possible experience under the conditions of measurement. It is less a picture of an observer-independent world than a framework specifying how observations arise from our experimental engagement with it.

See The Roles Ascribed to Conscousness in Quantum Physics (.pdf) He's also done a set of interviews with Robert Lawrence Kuhn recently.

-

Cosmos Created MindThe real world object (rock, tree...) exists irrespective of our ever having perceived it — Relativist

This is the whole point at issue. I've given my reasons in detail, if you can't see them, so be it, (although it might be noted that AI has no trouble understanding them). But I see no point in responding further, I'll leave it at that. -

Cosmos Created Mind‘Does the moon continue t exist when nobody is looking at it?’ Einstein asked Abraham Pais.

Why do you think he asked that question? -

Cosmos Created MindWell said!

you still have provided no justification for the ontological claims I highlighted:

.....

- that the supposed ‘unperceived object’ neither exists nor does not exist. Nothing whatever can be said about it. — Relativist

My claim arises in response to the familiar objection: if idealism is true, does an object cease to exist when no one is perceiving it? Berkeley famously answered this by invoking God as the perpetual perceiver. I’m not taking that route.

My point is more basic and logical than theological. If you take any object — this rock, that tree — and ask, “Does it exist when unperceived?” you have already brought it into cognition. To refer to it, designate it, or even imagine its absence is already to posit it as an object for thought. The very act of asking the question places the object within the space of meaning and predication.

So when I say that an unperceived object neither exists nor does not exist, I am not saying that objects go in and out of reality. I am saying that outside all possible cognition, conception, designation, or disclosure, there is nothing of which existence or non-existence can be meaningfully asserted. You cannot truthfully say “it exists,” because existence is never encountered except in disclosure. But you also cannot say “it does not exist,” because there is no determinate object there to which the predicate “non-existent” could attach.

Accordingly, existence and non-existence are not free-floating properties of a reality wholly outside cognition; they are predicates that arise only within the context of intelligibility. Outside that context, nothing positive or negative can be said at all. It's not a dramatic claim. -

Cosmos Created MindAgain: Demonstrate how "cognition" is "more fundamental" than whatever is (i.e. nature) that embodies "acts of understanding". A 'Machine in the Ghost'? (pace Bishop Berkeley) — 180 Proof

That's confused. What I'm saying is that cognition is a constructive and active process. The mind is not a blank mirror which simply reflects or receives what is already there. It is continually interpreting and synthesising whatever it perceives into its internal world-model. That is enactivism and embodied cognition. So I'm saying, that process of cognition and assimilation is what is truly fundamental - not the ostensible primitives of physics. I'm arguing that the world that we perceive as separate and apart from ourselves is in that sense a mental construct (Vorstellung in Schopenhauer.) And that 'objectivism' forgets this, and imagines that it sees the world as it would be with no observer in it. That is the argument in a nutshell. -

Cosmos Created MindThis is an unjustified statement: you have provided no basis to claim reality has a mental aspect. — Relativist

But you do understand when you say this, you are assuming that the world is mind-independent - that reality is outside of us, and our mental picture is inside our minds. This, to you, is so obvious that it can't be questioned - but it is what I am calling into question.

The view I’m defending is closer to a cognitivist idealism than to any denial of science or of an external world. The claim is not that reality is “mental stuff,” but that what we know as a world — objecthood, existence, lawfulness, measurability — is intelligible only through the constructive activity of brain/mind. The mind is not a mirror of nature, as if there were mind here and world there as two independently existing domains. Mind and world are co-arising, not separable in that way. Because, how would you know what the world is, without mind?

So when you say I lack justification for speaking of a “mental aspect” of reality, that objection already presupposes the very mirror-of-nature model that is under dispute. It also implicitly assumes a standpoint outside cognition itself — as if one could survey both “mind” and “world” from some position beyond one’s actual living cognition of either. -

Banning AI AltogetherI don't think the advent of ChatGPT changes anything in her article. — Leontiskos

Yes, true, that. I went back and looked again. What i siezed on first time around was her mention of the Blake LeMoine case which was discussed here at length. I agree with her conclusion:

"For now, if we want to talk to another consciousness, the only companion we can be certain fits the bill is ourselves."

Furthermore, I know a priori that LLMs would affirm that. -

Cosmos Created MindYou accept that the universe existed billions of years ago, despite it not having actually been perceived (so...does inferred count?) — Relativist

I note this objection at the outset. 'Science has shown that h. sapiens only evolved in the last hundred thousand years or so, and we know Planet Earth is billions of years older than that! So how can you say that the mind ‘‘creates the world”’? I also say that 'there is no need for me to deny that the Universe is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe exists independently of any particular mind. But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.'

Do you see the point?

These are unsupported assertions about the nature of existence. — Relativist

It is supported by the above. The argument is that 'existence' is a compound or complex idea, not a binary 'yes/no': it's not always the case that things either exist or don't exist, there are kinds and degrees of existence. The key point is that our grasp of the existence of objects, even supposedly those that are real independently of the mind, is contingent upon our cognitive abilities. Physicalism declares that some ostensibly 'mind-independent' object or state-of-affairs is real irrespective of the presence of absence of any mind - that is what is being disputed (on generally Kantian grounds).

On the other hand, your only justification seems to be that physicalism is false, therefore your view must be true. — Relativist

Physicalism is highly influential in modern culture. Much of modern English-speaking philosophy is based on a presumptive physicalism, and it's important to understand how this came about. So the argument I'm putting is not peculiar to me but to many other critics of physicalism.

having a perspective doesn't entail falsehood. If you accept science, then you have to accept that our human perspectives managed to discern some truths about reality - truths expressed in our terms- but nonetheless true. (I discussed the role of perspective in the post that led to your dropping out. Considering the importance you place on perspective, it's something you need to be able to address). — Relativist

I don't say that having a perspective entails falsehood. Nor do I dispute scientific facts.'I am not disputing the scientific account, but attempting to reveal an underlying assumption that gives rise to a distorted view of what this means. What I’m calling attention to is the tendency to take for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution. This oversight imbues the phenomenal world — the world as it appears to us — with a kind of inherent reality that it doesn’t possess. But nor am I advocating relativism or subjectivism - that only what is 'true for you' is real. Only that the subjective pole or aspect of reality is negated or denied by physicalism, which accords primacy to the objective domain, neglecting the foundational role of the mind in its disclosure. -

Cosmos Created MindI don't see any examples on this thread of anyone using physicalism as an ontological category. — 180 Proof

Relativist has made this claim repeatedly in numerous discussions over the past year. We've extensively discussed D M Armstrong's 'Materialist Theory of Mind', as recently as a few pages back. Armstrong's is the textbook example of physicalism as an ontology.

Physics is grounded in such irreducible acts of understanding ~ Wayfarer

Nonsense. "Physics is grounded" in useful correlations with natural regularities or processes. — 180 Proof

They are correlations between observations and mathematical calculations. Which, incidentally, have yielded insights into physical principles far beyond the scope of un-aided observation, purely on the basis of Wigner's 'unreasonable efficacy of mathematics in the natural sciences.' Dirac's prediction of anti-matter is a boilerplate example. Such calculations are purely intellectual in nature, then correlated against observations, so far as they can be (and as you note with many gaps.)

So when you insist that everything is “physical,” you are making a metaphysical assertion, not a scientific one ...

Well, since no one has made such a "metaphysical assertion", Wayf, your statement is, at best, just another non sequitur. — 180 Proof

Your 'fundamental ontological primitive', defined in negative terms, is of course a metaphysical assertion.

You constantly use the description 'non sequiter' to describe things you can't understand or don't agree with. Nothing I've said here or elsewhere in this thread is a non sequiter. -

Cosmos Created MindI can see perfectly clearly the background to this interminable debate - the aftermath of Cartesian dualism, the division of the universe into mental stuff and material stuff, the incoherence of the idea of mental stuff, the subsequent attempt to define everything in terms of matter and energy.

-

Cosmos Created MindThe core problem is this: physicalism treats “the physical” as the fundamental ontological primitive, yet physics itself does not—and cannot—define what 'the physical' ultimately is. The content of physics is a sequence of evolving mathematical formalisms, not an account of what being physical means in itself. (The fact that you say that the definition entailed by physics is not relevant to your claims only serves to underline, not defuse, this point.)

So when you insist that everything is “physical,” you are making a metaphysical assertion, not a scientific one—while simultaneously denying the legitimacy of metaphysics. That is the equivocation.

My point is precisely that you cannot justify treating “the physical” as the basic category of being when you cannot even say what it is, except by contrast with “the mental.” That inability is not a flaw in my argument—it is the unresolved foundation of your position.

The position I defend is that the mathematical models used to analyse the physical domain are themselves intellectual structures, consisting of meanings, identities, and necessities that can only be grasped by rational understanding. No equation, proof, or law functions as physics in virtue of its physical inscription, but only in virtue of its intelligible content. Physics is grounded in such irreducible acts of understanding.

More fundamentally still, cognition—even in non-human animals—is not built up from meaningless physical atoms, but is organized through meaningful gestalts: structured wholes that are apprehended within a lived context of significance. Charles Pinter's 'Mind and the Cosmic Order' shows that this can be said even of insects. Meaning is therefore not something added to or emerging from a self-contained physical process; it is the form in which all cognition exists.

If that is so, then neither rationality nor meaning can coherently be treated as derivative products of a domain that is itself defined only in abstraction from them.

That is the basic argument presented in the Mind Created World, which I don't believe you have countered.

If you have anything other than ad homs, sarcasm and emojis, this would be a good time to provide it. -

The Mind-Created WorldIt was the substance of the famous debates between Bohr and Einstein that occupied decades. At issue was the status of objectivity, about the question as to whether the primitive elements of quantum theory were indeed mind-independent. Einstein held a strong belief in realism, the view that physical systems possess definite, objective properties (like position or momentum) that exist independently of whether they are observed or measured.

He argued that quantum mechanics (specifically the Copenhagen interpretation associated with Bohr and Heisenberg) was an incomplete theory because its mathematical description (the wavefunction) does not account for these definite, pre-existing properties of individual systems. Bohr, the chief architect of the Copenhagen interpretation, argued that quantum mechanical elements do not possess definite properties until a measurement is made. The act of observation, through interaction with a classical measuring device, is what forces a quantum system to acquire a definite state (the "collapse" of the wavefunction). Einstein believed that a complete theory must provide a description of reality that is objective and local. That was behind the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) thought experiment (1935), where he used the concept of entanglement to argue that particles must have definite, pre-existing properties before measurement, or else quantum mechanics violated the principle of locality. As is well-known, experimental evidence after Einstein's death did confirm that quantum mechanics violated the principle of locality, the subject of the 2022 Nobel Prize. -

Cosmos Created MindWhat I'm looking for is your own epistemic justification to believe what you do. You previously shared the common view - it was a belief you held — Relativist

I've laid it out in the OP, The MInd Created World. It makes a rational case for a scientifically-informed cognitive idealism. We had a long discussion in that thread. We'll always be at odds. Simple as that. -

Banning AI AltogetherNotice that OP was published five months before ChatGPT went live. Apropos the problem posed in the thread, there is no way to put this particular genie back it's bottle. ChatGPT has the largest take-up of any software release in history, it and other LLM's are inevitable aspects of techno-culture. It's what you use them for, and how, that matters.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum