-

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I understand that you want to argue against the "view from nowhere". I'm not trying to argue for it, but I don't think that you can just stipulate having a perspective as a pre-condition. But perhaps I'm not understanding your point. — Luke

My point is that we view the world in a particular way that depends on the kind of physical and perceptual characteristics we have (in our case, as human beings). We explain the world in terms of observable distinctions (such as the distinction between red and green objects). It's a mistake to suppose that one can "get behind" one's perception and invalidate those distinctions when one's perception is assumed in the attempt.

I can't directly show you my perceptions or sensations, and neither can anyone else. — Luke

That's a Cartesian view of perception and experience. But ordinary perception and experience involves contact with the world which grounds our language and communication.

So when you and I observe this red apple we are perceiving the same red apple. That's our contact with the world, and I'm showing you what I'm perceiving.

Is that an infallible demonstration? No. If you're dichromatic, the red apple will appear dim yellow to you. But even in that case, your perception of the apple is not private or ineffable since I just described it.

We can do that, but it's not directly comparing our perceptions or sensations. Consider Locke's spectrum inversion: Since we both learned colour words by being shown public coloured objects, our verbal behavior will match even if we experience entirely different subjective colours. It seems to me more likely that what "straight" and "bent" looks like to you will be the same as what they look like to me, but the same issue could apply if only as a matter of degree (or perhaps if I had some sort of condition or brain malfunction that made me see differently than most people). — Luke

Yes, a red apple could appear green to Alice and vice versa. But there would be a relevant physical difference between Alice and Alice's twin who sees things normally. This difference is potentially discoverable, and therefore potentially comparable. That is, if discovered, Alice would then know that red apples appear green to her. Just as a dichromatic already knows that red apples appear yellow to them.

I don't disagree that our minds have a physical basis, but I don't see why the same "privacy in practice" doesn't equally apply to everyone, including statistically "normal" people. This could be another case of spectrum inversion, in principle. — Luke

Could be. But once it is recognized that this is due to some physical difference (and not radical privacy or ineffability), then there is no longer a philosophical hard problem. Investigating physical differences is within the scope of scientific inquiry.

What I'm arguing for is that our experiences are not radically private or ineffable (which our public language attests to)

— Andrew M

How does our public language attest to the fact that you see the same colour as I do when we both refer to "red"? How can our public language help to show me your sensations? — Luke

There's no guarantee it will. However when differences in people's observations are detected (such as a failure to discriminate colors), language can be used to describe it. For example, the dichromatic's experience can be described, and so is not radically private or ineffable.

and also that we represent the world from a particular perspective (since our public language reflects the natural distinctions we make when we observe and interact in the world).

— Andrew M

I don't believe that it is a "particular perspective", unless you mean some ideal, statistically normal "average person" - which is not a view from nowhere, but not a view from somewhere, either. — Luke

Everyone has their own perspective. But language norms emerge. This works in practice because we are observing the same world, have generally similar physical and perceptual characteristics (as human beings), and the same laws of nature are operative for each of us (principle of relativity). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Yes, but could B&W Mary know what yellow looks like before seeing it? — Marchesk

I think that with her knowledge Mary could have learned to visualize yellow before seeing it (in the world). Whether or not she would make that connection when later seeing a yellow object, I don't know.

Similarly consider: could Mary know what a circle looks like before seeing one? Or a $50 bill? Or a bent stick?

Of particular relevance to this thread, is visualizing (and dreaming, imagining, hallucinating, etc.) a form of seeing or perception? Or are they different kinds of activities? -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"A logical condition of what? Or, what do you mean by a "logical condition"? — Luke

A perspective (or a point-of-view) is a logical precondition for making natural distinctions and observing things.

Consider Alice taking a photograph of a landscape. A logical precondition is that she needs to be standing somewhere, and thus will be taking the photograph from a particular perspective. She can't be standing everywhere, and she can't be standing nowhere.

Alice points the camera, presses the button and the camera takes the picture. That's a physical process. At the end of that process, Alice has a snapshot of the landscape from a particular perspective.

So the photograph doesn't represent an objective "view from nowhere." Which is an analogy for the situation humans are in with respect to the world they are embedded in. They have a perspective of the world, and use human language to express that perspective.

I take it there is a particular way things seem to you at particular times, including the way things look, sound, smell, taste and touch. Simply because science cannot directly observe this particular way things seem to you, and/or simply because no direct intersubjective comparison is available, does not make these into "ghostly entities". — Luke

Intersubjective comparison is available via public language. We can both agree that the straight stick appears bent (when partly submerged in water) because we can point to actual bent sticks and recognize the superficial similarity.

Similarly, normally-sighted people can distinguish red, green and yellow apples, so there's nothing ineffable in saying that red and green apples appear dim yellow for dichromatics. And the dichromatic will agree they all appear dim yellow. That the dichromatic lacks the ability to distinguish these three colors is a kind of privacy in practice, but not in principle, since their lack of color discrimination has a physical basis.

It is only a subject who has a perspective of the world (object), so how can this be a rejection or replacement of the subject/object duality? It seems more like a bolstering of it. — Luke

The subject/object duality that I'm arguing against is the idea that a person has radically private and ineffable experiences and, on the other hand, that the world can be represented independent of a perspective. Neither are true.

What I'm arguing for is that our experiences are not radically private or ineffable (which our public language attests to) and also that we represent the world from a particular perspective (since our public language reflects the natural distinctions we make when we observe and interact in the world). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"So where does the red come from? — Marchesk

It's an empirical question. The conceptual point is that the natural distinctions people make (and which can potentially differ depending on the person or animal involved) need not be the same as the distinctions a scientist might make in their specialized field (in this case, regarding light wavelengths). Similar words may be used, but with different uses.

A simple example that shows this is with the yellow emojis and avatars on this forum. They are not reflecting yellow light (since computer screens emit red-green-blue light). Whereas a banana is reflecting yellow light. The relationship between those different distinctions can be investigated empirically, and without assuming an ontological subject/object division. -

Keith Frankish on the Hard Problem and the Illusion of QualiaPhilosophy Bites Podcast

The podcast is only 15 minutes. The two hosts interview Keith Frankish about his position on the hard problem. — Marchesk

I think you meant to link to the podcast here from Oct 11, 2014. The podcast you linked to is on Conscious Thought from Jan 15, 2017 (and is 12 mins long).

The Conscious Thought podcast made perfect sense to me and qualia wasn't mentioned at all. Whereas in the hard problem/qualia podcast, Frankish seems to accept qualia as an apparent phenomena to explain (i.e., which he goes on to say is an illusion), rather than rejecting wholesale the subject/object dualism that gives rise to it. Unlike Frankish, it doesn't seem to me that we experience qualia, so there's nothing to explain (or explain away). Instead, it seems to me that we experience the world, which includes sunsets and red apples and human beings. And those are the things that we seek to explain. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The hard problem arises as a result of positing an ontological division between one set of features and the other. That is, a solution becomes impossible in principle because it has been defined that way.

— Andrew M

Seems that way to me as well. Dennett also pointed it out. — creativesoul

Yes, I briefly discussed Dennett's Cartesian Theater metaphor here. And, of course, Dennett points out how qualia is defined to be beyond the scope of science (radically private, ineffable, etc.). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Wouldn't you say that having a perspective (or being conscious) is a bodily process or function like any other? — Luke

No. As I'm using the term, it's a logical condition.

I think you and I might have different conceptions of a human perspective. Yours is apparently stripped of all phenomena leaving only an abstract point-of-view singularity. Whereas I see little difference between having a perspective and being conscious (in the first-person), with all that that entails. — Luke

Yes, my usage here is the former. However, your alternative usage is fine as well (i.e., the result of having observed, made distinctions, drawn conclusions, used language). In this case, like the "winning the race" example, it would be a logical condition that denotes the end of a process - something that is achieved by looking, thinking, interacting in the world, etc. Which is just what it means to be conscious. However I don't accept the "first-person" qualification if it's meant to imply a contrast with a "third-person" perspective.

Do you consider observation to be a part of a perspective? — Luke

Observation is an activity or process. Perspective is the prior condition (my usage) or the end result (your usage) of that activity.

I think that human aspiration or human digestion could be said to have physical existence? — Luke

OK.

As I see it, the first-person/third-person division excludes the possibility of a physical explanation

— Andrew M

Why does it? — Luke

In effect, it posits ill-defined ghostly entities that are outside the scope of scientific investigation. See my earlier post on this here.

If these are properties of the apple, rather than properties of your perception (or rather than some relation of the two), then it would seem to imply that the apple is objectively spherical and objectively red. Which is fine, but how do you deal with things like seeing illusions where there is a discrepancy between the properties of the object and the perception of the object? — Luke

If there's a known discrepancy, then we ordinarily express that by saying, for example, "The stick is straight but appears bent". However if someone simply said that the stick is bent (when it is straight), then they would be mistaken.

I'd just add that the 'objective' qualifiers are misleading, since they imply that the apple has those characteristics independently of a perspective. It's both sides of the subject/object duality that need to be rejected and replaced with a perspective of the world conception. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia":up: Perspective is an attribute of rational thought. Do non-rational animals entertain perspectives? I think not, because they are not capable of abstraction. — Wayfarer

Yes, I think that's true for a self-reflective sense of perspective. However I'm just using it in the sense of a reference point from which things are observed. Animals can still distinguish objects and colors, even though they lack an ability to use language to represent them.

I have to draw attention again to the equivocal meaning of ‘substance’ in this context. ‘Substance’ in normal usage means ‘a particular kind of matter with uniform properties’. ‘Substance’ in the philosophical sense means the fundamental kinds or types of beings of which attributes can be predicated.

So I think what you are actually saying here, is not 'substantial', but 'material' - you're contrasting material particulars with abstractions. — Wayfarer

The types and kinds that you're referring to are what Aristotle termed secondary substance. So 'tree', 'apple', and 'human' are all secondary substances. However concrete particulars are primary substances. This tree here, that red apple on the table, and Socrates are all examples of primary substances. For Aristotle, the kind apple depends on there being individual apples. So secondary substance is not separable from primary substance.

This is central to Aristotle's discussion of change. What is substantial to a thing is that which does not change for that thing during its lifetime. Thus Socrates might change from pale to tanned, or healthy to sick, but he is always human (and he is always Socrates).

From SEP:

The individual substances are the subjects of properties in the various other categories, and they can gain and lose such properties whilst themselves enduring. There is an important distinction pointed out by Aristotle between individual objects and kinds of individual objects. Thus, for some purposes, discussion of substance is a discussion about individuals, and for other purposes it is a discussion about universal concepts that designate specific kinds of such individuals. In the Categories, this distinction is marked by the terms ‘primary substance’ and ‘secondary substance’. Thus Fido the dog is a primary substance—an individual—but dog or doghood is the secondary substance or substantial kind. — Substance - SEP

They [abstractions] depend on (are not separable from) concrete particulars. They exist, to the extent that they do, because the concrete particulars that they are predicated of exist.

— Andrew M

But that leads to the question of what 'dependency' means. If you consider such concepts as fundamental logical laws or arithmetical principles, there are at least some that are understood to be 'true in all possible worlds'. Basic arithmetical principles, such as number, are applicable to any and all kinds of particulars; '3' can be predicated of people, apples and rocks. So I question this notion of 'dependency'. — Wayfarer

What I've described is Aristotle's notion of dependency. For details, see Aristotle's four-fold classification of beings in the Categories. There's a useful chart at 8:40 in this video (Substance and Subject) by Susan Sauvé Meyer. The arrows show the dependencies of universals and inherent items on concrete particulars (primary substances).

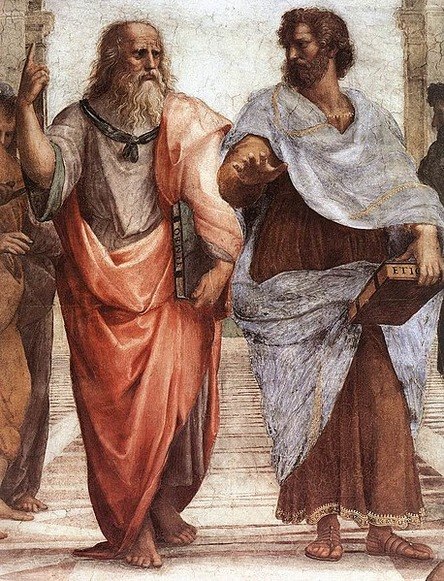

This inverts Plato's scheme since, for Plato, concrete particulars are dependent on the Forms. As Meyer concludes (from the Video Transcript):

The main point to keep in mind is that the term substance in our translation of Aristotle is standing in for ousia, which we can think of as the gold medal winner in the ontological olympics. With this understanding of ousia, we can see that it has the ontological status that Plato attributed to his intelligible forms. So now we can articulate the ontological dispute between Plato and Aristotle. Plato thought that the entities that deserve the title Ousia, the most fundamental entities, are suprasensible, intelligible forms. Aristotle, by contrast, thought that the most basic realities are those that serve as subjects for all the rest. And these are such ordinary entities as human beings, and other animals. — Substance and Subject - Susan Sauvé Meyer - University of Pennsylvania -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"If a perspective is no different to aspiration, perspiration and digestion in terms of their inseparability from human activity, then why does a perspective differ in terms of having substantial existence and properties? — Luke

The difference is that aspiration, etc., are bodily processes or functions. Whereas a perspective is a logical condition for being able to make distinctions.

Compare running a race to winning a race. Both are predicated of people (i.e., are not separable from people). But they are different kinds of predicates. Running is a physical process, whereas winning is the logical condition of having passed the finish line first and is not itself a process. (This is Ryle's distinction between try and achievement verbs.)

But we don't observe a perspective. — Luke

We don't, but it is implied in a person's activity which we do observe.

What I'm questioning about the analogy is your statement that we have a perspective just like we (or other objects) have a reference frame, and yet neither of these has substantial existence. I think I'm still not sold on what you seem to be implying: that we can have them without them existing. — Luke

Concrete particulars such as people, apples and rocks have substantial existence, being substances. Abstractions do not. They depend on (are not separable from) concrete particulars. They exist, to the extent that they do, because the concrete particulars that they are predicated of exist.

Linguistically, we wouldn't normally say that breathing exists, we would say that a person breathes (though we might say that their breath exists - however this refers to the air, which is itself substantial). Similarly, we wouldn't normally say that perspectives exist, we would say that a person has a perspective. So the non-separability (and thus the dependent and abstract nature) of those predicates is clear.

I should probably make clear that I have no interest in preserving 'res cogitans' or the human perspective as a non-physical substance. I am looking for a purely physical explanation, but one which retains the first-person perspective and the reality of its properties/qualities. — Luke

As I see it, the first-person/third-person division excludes the possibility of a physical explanation (hence the hard problem). Instead, as human beings, we have a perspective on the world. That's the logical condition for being able to make any distinctions at all. So, from my perspective, the apple is spherical and red (i.e., they are properties of the apple). Not that the apple is objectively spherical and subjectively red (which is subject/object dualism). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Their perspective is not a "thing" that has any existence separate from that human activity. But we can consider it separately (i.e., in an abstract sense).

— Andrew M

In the same way that e.g. breathing, perspiration and digestion are not "things" that have any existence separate from human activity? Or, in the same way that the game of chess and economic markets are not "things" that have any existence separate from human activity? — Luke

Yes, that's right. For the first set of examples, if a person dies, they no longer have a perspective on the world - that perspective depended on them being a living, functioning human being. For the second set of examples, these things perhaps exist as artefacts of human activity (and thus don't literally depend on humans to always be there), but nonetheless gain their meaning and purpose by virtue of a human perspective (or perspectives).

Does separability from human activity help to decide whether these "things" are physical or real? — Luke

I'm not sure I understand your question. In an everyday sense, we regard the things we can observe as real. Those things are separable from human activity. For example, red apples preceded human existence.

However identifying and talking about those things isn't separable from human activity. So, from my perspective, that's a red apple there (that existed prior to my interaction with it). But that perspective may not be relevant to an alien creature with a different perceptual capability, since their perspective may be different. So you can't necessarily generalize one's perspective to other creatures (or, in certain cases, even to other humans if they can't make the same distinctions that you can - their perspective would be different).

Are perspectives identical to reference frames, then? Is a perspective also "an abstract coordinate system that measurements are made relative to"? If it's not the same, then in what way is it comparable? — Luke

It's analogous, but not quite the same. A perspective is a reference point that observed distinctions are made relative to.

Also, a perspective is applicable to human beings and, potentially, other sentient creatures for whom it makes sense. But not trees or rocks (which nonetheless qualify as reference frames).

Also, two objects can be in the same inertial frame, whereas a perspective is ultimately unique to an individual. However, we are a part of the same world, have similar physical characteristics, and the laws of nature are the same for both of us. So most of the distinctions and statements that would be valid and true from my perspective would also be valid and true from yours.

The words in a statement such as "the apple is red" derive their meaning from (i.e., are grounded in) a human perspective. The main point of comparison with relativity is that distinctions/measurements are relative to some reference point, not absolute. That is, the perceiver is implied in any statement about the world. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"All of these features are part of the world as we perceive it. Without that perspective - our primary point of reference in the world - nothing is distinguished or defined at all.

— Andrew M

'Perspective' implies or requires an observing mind, does it not? I mean, it is something I'm in complete agreement with, but it seems to me that it is more often than not overlooked. — Wayfarer

Seems OK to me. This is what I mean by saying that there is no view from nowhere. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"That has to do with the speed of light and inertial frames, not perceivers. Perceivers are only used for thought experiments to show their clocks and measuring-rods are different, but there's no need for that. Happens for any objects and events. — Marchesk

Yes it happens for any object and event - which are distinguishable in human perception.

As with the train speed example, there is no "view from nowhere".

— Andrew M

But there is, because life evolved long after the universe was around, and science can detail the universe in places where there is no life and no perceivers. — Marchesk

Yes it can. I can point to the Sun and stars (a human perceptual activity) and we can agree that that is what we mean by those terms. It doesn't follow that the Sun and stars didn't exist before we identified them (or before humans emerged). Same thing for red apples.

However, if you're arguing from a Kantian/correlationist position and not a realist one, then that's another matter. I'm pretty sure Dennett is a realist/physicalist, as is Chalmers, except for consciousness.

I'm not sure the consciousness debate matters for Kantians, since the empirical world includes all the colors, sounds, etc. So I get why you would deny Nagel's "view from nowhere". The consciousness debate seems to only matter for physicalism, pun unintended. At least that's how Chalmers approaches it, with his talk of supervenience and p-zombies. — Marchesk

No, I'm not a Kantian. My view is broadly Aristotelian, which is realist. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"A human being has a perspective of the world. The distinctions we make and our representations of the world presuppose that human perspective. But that perspective doesn't itself have properties (qualia) or a substantial existence (res cogitans), contra dualism.

— Andrew M

To echo Marchesk’s post, if we have perspectives - if our perspectives exist - yet they do not have substantial (physical?) existence, then what type of existence do they have? — Luke

It's a formal aspect of a human being perceiving the world. Their perspective is not a "thing" that has any existence separate from that human activity. But we can consider it separately (i.e., in an abstract sense).

For an analogy from physics, consider an inertial reference frame. In the train platform's frame, the train is travelling 60mph. In the train's frame, the train is at rest. So what is a reference frame? It's simply an abstract coordinate system that measurements are made relative to. It doesn't have an existence beyond a location in space (such as the train or platform) that is represents.

A person's perspective is like that. It's an abstraction that doesn't exist separately from the person interacting in the world. Yet it is assumed in the distinctions, observations, and measurements that the person makes. As with the train speed example, there is no "view from nowhere". -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"However, if that perspective is is coloring in the world, adding sound, taste, smell and various feels, then we're still left with something that needs to be explained, because the rest of the world isn't colored in, doesn't have feels and tastes and what not. It's only that way to a perceiver. So somehow the perceiver adds those sensations to their interaction with the world. The hard problem remains in some form until there is some way to account for these sensations. — Marchesk

You're describing the world as a barren landscape where the human comes along and colors it in with all the qualities that make it interesting to them.

But a different view is that the world already has qualities as well as quantities, particulars, relations, actions, events, etc. If so, then making a distinction between in-here and out-there, or subjective and objective, is a philosophical mistake. All of these features are part of the world as we perceive it. Without that perspective - our primary point of reference in the world - nothing is distinguished or defined at all.

And yes, perceivers are part of the same world, not walled off from it, but still the question needs to be answered: from whence comes the colors, sounds, etc? — Marchesk

But also whence comes distance, mass, time, motion, molecules, plant life and lower organism sentience?

These features are all defined in reference to our human perspective (consider Einstein with his measuring-rods, clocks and observers giving an operational meaning to his relativistic theories). The hard problem arises as a result of positing an ontological division between one set of features and the other. That is, a solution becomes impossible in principle because it has been defined that way. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"this just comes down to whether one accepts the philosophical subject/object distinction or not. As I've mentioned before, I reject it.

— Andrew M

You cannot actually reject anything if you are not a subject. — Olivier5

You can't reject anything if you're not a human being. But that doesn't imply subject/object dualism, which divides the human being in Cartesian terms. (Which I briefly discussed here.)

A human being has a perspective of the world. The distinctions we make and our representations of the world presuppose that human perspective. But that perspective doesn't itself have properties (qualia) or a substantial existence (res cogitans), contra dualism.

It's a different perspective to dualism, so to speak. -

There is definitely consciousness beyond the individual mindAbsolutely, and I want to say your use of "shiny" is not coincidental. — Srap Tasmaner

Yes, tools not sullied by having any practical use in the world. Yet, as ideals, often attractive and tempting...

That's a demonstration of something, but not of something anyone really needs. Back to the rough ground, and to tools that will improve with use on rough ground, and that means no glass-soled boots. — Srap Tasmaner

That's it. And I think this is an insightful way to think about ordinary language. It's often written off as naïve, pre-scientific, imprecise, plain wrong, and so on. But it has traction on the rough ground of everyday life. It's been thoroughly tested by constant use and evolution, and continues to get the job done. To riff off Austin, it may not be the last word, but it's worth taking the time to understand why it qualifies as the first word. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"apples don't look red in the dark, yet they are red

— Andrew M

Okay, whatever. It makes no philosophical difference that I can see to my perception of red. — Olivier5

Cool. It relates to philosophical issues such as dualism, qualia, the hard problem, and what not.

That is, apples don't look red in the dark, yet they are red

— Andrew M

That's two different meanings for the word "red". One is how it looks to us, the other is having the property of looking red to us under normal lighting conditions. That is to say, the chemical structure of the red apple's surface is such that it reflects visible light of a certain wavelength. — Marchesk

The word "red" has the same meaning in both phrases, it's just qualified in the first phrase. It's the same form as "the stick doesn't look straight (partly submerged in water), but it is straight."

Distinctions are made in ordinary experience. And those distinctions can be qualified (by "seems", "appears", "looks") in subsequent experiences. Only one meaning is operative here, not separate "subjective" and "objective" meanings. Again, this just comes down to whether one accepts the philosophical subject/object distinction or not. As I've mentioned before, I reject it. -

There is definitely consciousness beyond the individual mindAs someone with nominalist inclinations, I still find this charming, right down to the note of pragmatism: — Srap Tasmaner

Thanks for the shoutout. And a great Grice quote.

Along Grice's lines, a value of the forum is that one gets to try out one's tools on a variety of interesting problems and either improve them further, or learn about other tools that might do a better job.

The trick is to be actually using the tools to do the work (and, one hopes, making progress on the problems), and not just admiring them as they sit all shiny and untouched on the shelf. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"However that use is derivative from situations where we observe an object in normal lighting which is where color distinctions are originally made. That's the reference point in the world. Without that reference point, you have to contend with the private language argument.

— Andrew M

That I do agree with! — Janus

:up:

For colors, the looking and the being are dentical. — Olivier5

Yet we do make the distinction in practice - see below.

An apple that receives no light cannot absorb part of the visible spectrum and reflect the other. It has the pigments to do so but not the light that would be playing with the pigments.

There's more: in the absence of light, maturing apples will become pallish, not red. So apples need to sense some light in order to even bother producing pigments to color that light. The same apply to leaves: if kept in the dark for a while, they will lose their green chlorophyll and turn white. — Olivier5

Yes. So that's a physical process. In the absence of light, the colors of the apples and leaves change over time independently of anyone being there. So looking red (or pallid, or green, or white) and being red (or pallid, or green, or white) are different. That is, apples don't look red in the dark, yet they are red (until they become pallid). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"You want to privilege one usage of the term over the others, and that says more about your own preference than it does about common usages. — Janus

No, it's about being clear on what the usages are and how they relate to each other. When says that "All cats are grey in the dark", I understand what he's saying. It's equivalent in that context to saying, "All cats look grey in the dark". No disagreement from me.

However that use is derivative from situations where we observe an object in normal lighting which is where color distinctions are originally made. That's the reference point in the world. Without that reference point, you have to contend with the private language argument. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"What colour it is is how it appears under some specific "normal" conditions; what's the problem with that? — Janus

None, in the sense that they both have the same truth conditions in that situation. It doesn't follow that "what color it is" and "how it appears" have the same use or meaning. The difference is that how the apple appears can change under different conditions. Whereas the apple's color does not.

No, the apple appears red to the colourblind person, just as it does to us "normal" people. That is to say it appears as a colour that he calls red, just as it appears to us as a colour we call red. It just so happens that those two colours, those two appearances are not the same. — Janus

On that basis, the apple would also appear green to the colorblind person since they can't distinguish those colors. So it would appear green and red at the same time. If that sounds odd, it's because we don't define "red" and "green" in terms of how things appear to a color-blind person. And neither does the color-blind person.

Further, we find on analysis that the term "appears" doesn't designate subjective "appearances". It is instead a term that lets us say how two different situations are, in some sense, similar.

— Andrew M

This can't be right because you have said that the apple appears different to a colourblind person than it does to a "normal" person. — Janus

And so it does. You can see here that red and green apples appear dim yellow for dichromatics.

But I reject the subject/object distinction that's implied by subjective "appearances" (i.e., mental entities or mental experiences).

You haven't said what it would mean (beyond the merely conventional usage) to say that an apple is red when no one is looking at it or when it is in the dark. — Janus

Color terms refer to a physical aspect of objects. As abstractions, it doesn't matter what the physical details are - that's a scientific question (which, we've learnt, are the light reflective properties of the object's surface). If no-one is looking or it is dark, that physical aspect of the apple is still there. That the apple isn't being looked at, or appears differently in the dark, doesn't change that physical aspect. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Sellars went through all this in "Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind" too: "looks" talk, as in "the apple looks red to Andrew", is logically posterior to "is" talk. There's no way even to make sense of it otherwise. What does it mean to say that an apple looks red except that it looks like it is red? — Srap Tasmaner

Indeed. That's a clear and concise way to put it. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The word "red" picks out a physical aspect of the apple, not how it appears (which is a qualifier meaning "seem; give the impression of being", not a reference to a mental entity or mental experience).

— Andrew M

The apple appearing red came long before optics. — Marchesk

Yes, it did. Now consider whether there is something about the apple that would cause the apple to appear red to us. That "something" is what the word "red" picks out, not how the apple appears to us. How the apple appears to us is part of our experience, not part of the apple. Thus there is a difference between being red (which is a feature of the apple) and appearing red (which implies a perceiver). -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Here's a neat quote from Austin that gives an idea of how he thought about ordinary language:

"First, words are our tools, and, as a minimum, we should use clean tools: we should know what we mean and what we do not, and we must forearm ourselves against the traps that language sets us." — Banno

:100: I think the word "appears" is one of those potential traps. It takes on a life of its own in philosophy! -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"As I've already agreed, the common usage of the term 'red' is fine. — Janus

I'm not sure it is fine for you, since you think that red, when analyzed, actually refers to how the apple appears, not what color it is. But my argument showed that it can't be referring to how it appears, since how it appears drops out in use. That is, even the person who is wired differently says the apple is red because "appearances" can't be compared between two people. Instead they can each only say that they are able to distinguish two differently colored apples and then use a color naming convention that captures that distinction. (For example, that "red" is the word we use to describe stop signs, and "green" to describe grass. Since this particular apple situation is similar to a stop sign situation and not a grass situation, then "red" is the correct term to describe it.)

That is a version of the private language argument.

Further, we find on analysis that the term "appears" doesn't designate subjective "appearances". It is instead a term that lets us say how two different situations are, in some sense, similar. For example, that wearing red-green inversion glasses makes the situation of seeing a red apple like the situation of seeing a green apple (even though we know that is not actually the situation). Compare with the example of the straight stick that appears bent in water. It's similar to seeing a bent stick, but we know they are different situations. The stick is straight, independently of how it appears to someone. And the apple is red, independently of how it appears to someone. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The apple is nonetheless red, but the animal is unable to perceive that.

— Andrew M

That the apple is not red to some animals implies that it is not red tout court, but that it has the constitutional potential to appear red to some animals. — Janus

No, the apple is red tout court.

The word "red" picks out a physical aspect of the apple, not how it appears (which is a qualifier meaning "seem; give the impression of being", not a reference to a mental entity or mental experience).

For example, suppose that some people have a genetic difference that results in brain wiring such that red apples appear green to them and green apples appear red.

They would learn to use the word "red" to describe red apples just the same as everyone else (since that is the convention). Their experiences are different from ours, unbeknown to us. But they correctly identify that the apple is red because the color term is picking out a physical aspect of the apple that is distinguishable by them (i.e., red from green), not how the apple appears to them.

If they put on red-green inverting glasses, they would then say that the red apple appears green to them, just as we would. So even though their experiences are different to ours, they are nonetheless using the color terms in the same way that we are. That's a proof, if you like, that color is a physical aspect of the apple, not a mental phenomenon. Instead it is theirs and our experiences that are different. And that experiential difference has a physical basis in the genetic/brain wiring difference.

For all we know it may appear as some other colour we have never perceived to some animal. Would you then say that the apple is that nameless colour tout court? Or if the apple is grey to an animal that has no colour receptors does it follow that the apple is also grey tout court? What I think you are missing is that colour is relational, not inherent, whereas the potential to be coloured is inherent. — Janus

The apple is red regardless, per the conventional use of the word "red". However there's no problem with having an alternative color language that denotes the color distinctions that a particular animal makes. And an animal that can't distinguish color at all is color-blind. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Fair enough, apologies for not reading the thread. — Olivier5

:up:

A signal calls for an action, typically. That's why it's urgent. It comes at a certain moment, when a certain action is required and not before. In this case, the apple turns red when it is ripe, i.e. when the fruit and its seeds are ready for cumsomption by animals. So basically the tree is calling an animal as a sort of taxi, when it's ready, to transport its kids to a new neighborhood (the seeds, that will be excreted a few miles away). The cab fare is the sugar in the fruit. — Olivier5

That's a great metaphor. Good post! -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The apple is nonetheless red, but the animal is unable to perceive that.

— Andrew M

Nonsense. — Olivier5

Here is the context from the quoted post that I was responding to:

"An animal that has no red photo-receptor cells in its retina cannot see red..." -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Isn't the domain of ordinary, everyday experience precisely what is categorized under 'folk psychology' by eliminative materialists? Isn't it precisely that which is to be superseded by properly-formulated scientific expression? — Wayfarer

That would be a case of throwing out the baby (ordinary language) with the bathwater (language implying ghostly entities).

"That there are features of the environment that are naturally distinguishable by normally-sighted human beings in decent lighting (whatever the physical details of that happen to be)." is basically the same story I told without specifying as many details as I included. — Janus

OK.

However, when you say unreflectively that an apple is red that should not be taken to imply that the apple is red when no one is looking at it, because colours are qualities that exist only by virtue of being seen. It is not wrong to say that apples are red, but it is merely shorthand for saying that we see apples as red.

An animal that has no red photo-receptor cells in its retina cannot see red, and so for that animal apples are not red. If humans had been lacking red photo-receptors then we would never have said that apples are red. So, beyond the context of ordinary communication, it seems to make no sense to speak of apples being red tout court. — Janus

The apple's composition is such that a normally-sighted person in decent lighting would use the word "red" to describe it. That is, for the apple to be red is for the apple to have that composition (which it has independent of being seen).

Human color terms won't necessarily be applicable when describing what other creatures perceive, as with your example. The apple is nonetheless red, but the animal is unable to perceive that. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Do you mean that under the 'normal' range of light temperature and intensity the constitution of what we call a red apple is such that its surface will reflect that part of the electromagnetic spectrum such as to appear red to any creature with the requisite visual system or something else? — Janus

No, it's more straightforward than that (or, at least, doesn't depend on language like "light temperature and intensity", "reflect", "electromagnetic spectrum", "visual system", "appear").

I mean that there are features of the environment that are naturally distinguishable by normally-sighted human beings in decent lighting (whatever the physical details of that happen to be). Further, it has been useful to create language to designate those features.

So the apple grower decides to categorize the apples here as "red" and the apples there as "green". When he explains this to his customers, they can also see the distinguishing features of the apples that he is pointing to. If that seems to them a useful distinction to make, they will go on to use those color terms as well. And so a new language use is born.

Now the scientist comes along and wants to investigate all this in further detail. He discovers that light has wavelengths which are reflected in different ways off different things and that this results in people perceiving things in specific ways. He decides to give color names to various ranges on the spectrum which have an approximate relationship to what people report, but also some differences. These scientific color terms are conceptually different to the color terms the apple grower uses. It's a bit like the relationship of polling to actual election results. Not totally unrelated, but should be understood to be different things.

The point to note here (which I tried to illustrate in the physics student story earlier) is that scientific language doesn't supersede conventional use. Instead, it logically assumes it. That is, the scientist's specialized language is ultimately grounded in ordinary, everyday experience. It's a human view of the world as distinct from a Platonic "view from nowhere". -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Ordinary language has naive realist assumptions. I really don't understand the obsession with ordinary language philosophy. Ordinary language has all sorts of assumptions baked into it. Why take those at face value? — Marchesk

I don't think it has the metaphysical assumptions you think it has, and the assumptions it does have (logical constraints, really) turn out to be very useful.

Instead think of ordinary language as a natural and useful abstraction over the physical processes that operate in our world.

Also, science doesn't say the apple is red, it says the apple reflects light of certain wavelength that we see as red. Important distinction. — Marchesk

Scientist: So in this experiment, I'd like you to push the red button when I say.

Philosophy student: There is no red button.

Scientist: That button right there in front of you.

Philosophy student: It's not red.

Scientist: What do you mean? Are you color-blind?

Philosophy student: No.

Scientist: Well what color do you think it is?

Philosophy student: It doesn't have a color. However there is red qualia in my mind that appears right where the button is. Maybe that's what you mean?

Scientist: That will be all, thanks. Could someone get me a physics student?

(A little while later...)

Scientist: So in this experiment, I'd like you to push the red button when I say.

Physics student: Wait a moment! (Get's out light detector. Measures wavelengths of light reflecting off the button. Checks chart to confirm within red wavelength range.) OK, that's red alright!

Scientist: OK... Couldn't you just like, I don't know, look at the button?

Physics student: No, I only trust what my light detector says. It's possible the environment, not to mention my visual system, was influencing what color I thought the button was.

Scientist: (Face palms.) OK, are you ready to push the red button now?

Physics student: Wait a sec. (Get's out light detector again.)

Scientist: What are you doing now?

Physics student: Well, I thought it best to check again. Repeatability and all that. Minimize the possibility of experimental error. Maybe I should get a different detector, just on the off chance this one is faulty.

Scientist: That will be all, thanks. I'll push the damn button myself! -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"I'm thinking a thread on The Concept of Mind might be fun.

Who's interested? An appropriate follow up to this. — Banno

:up: Definitely. Ryle's book was a landmark for me. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Would apples be red in the world of the blind? — Janus

Yes. Color terms are abstractions. Is the apple red even at night and even if no-one is looking at it? The answer again is yes, it is. That is, the apple is red independent of the environment external to it, including sentient human beings. Nonetheless, a human perspective is implicit in the forming of that abstraction.

If everyone were blind, no-one would have formed that abstraction. It would have no use. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"If the apple looks different to you than to me, then our experiences are different. That's a difference that is, in principle, discoverable.

— Andrew M

But not for creatures with sensory modalities different enough from us. — Marchesk

Do you mean we can't discover that their experiences are different or in what ways? I'm not color blind, but a quick look at the images on the color blindness Wikipedia page gives me a sense of how a color blind person would see things, and thus how their everyday experience would differ from mine. Similarly for animals, whose visual systems vary further, as you know.

That doesn't tell me much about bats, but I don't see an in-principle line that can't be crossed regarding future knowledge.

Experiences aren't limited to perception, and there is a limit to my ability to communicate what it's like to be me to you. We never fully know what other people experience. Their full feelings, dreams, thoughts, and being in their own skin is only something they experience. — Marchesk

Yet, still, we have empathy and shared experiences. I see the limits as practical, not as in-principle.

Even with perception, if the difference is great enough, we can't always know. Some have suggested there are tetrachromatic females who have more vivid color perceptual abilities. Their ability to communicate what that's like to us would be limited by our 3 primary color combinations, if this is indeed so. I believe the evidence is still inconclusive, though. — Marchesk

Sure. Though technological or biological modifications could conceivably be developed that alter one's experiences.

"Red" doesn't refer to an experience, it refers to the color of the apple.

— Andrew M

Apples aren't red. They reflect light in a wavelength range we see as red. Red is part of the visual experience. — Marchesk

You're speaking a different language to me, which is a philosophical choice. But on ordinary usage, as in scientific practice, there are red apples. In my view, ordinary language is straightforward, coherent and useful. And isn't susceptible to the kinds of philosophical problems that arise for subject/object dualism. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The equating of experience with qualia assumes dualism, which I reject.

— Andrew M

How? — khaled

See Dennett's Cartesian Theater or Ryle's ghost in the machine. Those are metaphors for subject/object dualism, where experiences are private to a subject (hence the need to posit qualia - the content of experience) rather than being a person's interactions in the world (the ordinary, everyday usage).

It's not just a matter of a simple word definition. Subject/object duality is a conceptual scheme that pervades philosophy, in various and often subtle ways.

The mind is not a container or a theater or something mysterious apart from the world, it's a way of talking about an agent's capabilities for engaging in the world. As Bennett and Hacker put it:

Talk of the mind, one might say, is merely a convenient facon de parler, a way of speaking about certain human faculties and their exercise. Of course that does not mean that people do not have minds of their own, which would be true only if they were pathologically indecisive. Nor does it mean that people are mindless, which would be true only if they were stupid or thoughtless. For a creature to have a mind is for it to have a distinctive range of capacities of intellect and will, in particular the conceptual powers of a language-user that make self-awareness and self-reflection possible. — Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience - Bennett and Hacker -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"What I meant was how do you confirm that the apple results in the same experience for everyone. You can't. You only know that it results in some experience we all decided to dub "red" (even though it might look different for everyone). — khaled

Just a heads up that we're using the word "experience" very differently.

If the apple looks different to you than to me, then our experiences are different. That's a difference that is, in principle, discoverable.

Well if it makes no physical differences then we have no reason to assume that the two people have the same experience but other than that I agree.

And Qualia, means specifically these experiences. So just because we can't describe the contents of our experiences to others (if my red was your green we would never be able to tell) doesn't mean those contents don't exist. — khaled

Not on the ordinary definition of experience (one's practical contact with the world). On that definition we can, and do, describe our experiences.

The equating of experience with qualia assumes dualism, which I reject. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"The solution, as I see it, is to put qualities like color, etc., back in the world where they belong. It is the apple that is red, there is not red qualia in people's minds

— Andrew M

But how come some (colorblind) people see the apple as green? — khaled

Because their visual systems differ from the norm.

And how do you confirm that the apple is in fact red? — khaled

By looking (if you're not colorblind). Or asking someone (if you are).

You can’t see the apple from my perspective to confirm that when you say “red” you are referring to the same experience as when I say “red”. — khaled

"Red" doesn't refer to an experience, it refers to the color of the apple. Now suppose I were feeling hungry, saw a red apple, and my mouth watered - that's an experience. It's an experience that you might have had as well. But perhaps you don't like red apples, so then your experience would be different.

The problem is this: we can confirm that we all agree on some properties of the apple/experience them the same way. Properties such as shape can be confirmed by asking someone to draw an apple and you’ll find people will agree on an apple’s shape. But someone can be seeing inverted colors from me and there will be absolutely no way to confirm or deny that. In other words, we can confirm the wavelength reflected off the apple, but we cannot confirm whether or not the experience produced when that wave enters our eyes is the same. — khaled

People may or may not agree on the apple's shape if they are wearing different kinds of distorting glasses. That is what colorblindness and color inversion amounts to. We would normally assume that two people who look at a red apple and say that it is red are having the same experience. However if their experiences were different, then there would be physical differences that account for it. -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"Yep. Talk of qualia distracts us from the world in which we are embedded. It's vestigial idealism. — Banno

:up: -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"But it’s there for very good reason, and it can’t easily be rejected. — Wayfarer

Yes, it requires a conceptual shift.

But it can be revealed through analysis.

It was Galileo Galilei who wrote ‘the book of nature is written in mathematics’ and whose legacy includes the astonishing leaps that science made in subsequent centuries. It is true that understanding the laws that govern just those attributes of bodies that can be made subject to precise quantification, combined with Descartes’ newly-discovered algebraic geometry, laid the ground for the ‘new science’ that is at the basis of modern scientific method, which has universal scope and application, and spectacular results, not least these amazing ‘typing machines’ we all seem to have nowadays. And you can’t let subjective preferences play a role in engineering specifications. — Wayfarer

What you're describing are the spectacular results that can be realized by effective mathematical abstraction. But, as I note below, it isn't necessary to adopt the Cartesian ontology along with it.

This is all the subject matter of another of Thomas Nagel’s books, namely, Mind and Cosmos. He says

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop.

(pp. 35-36)

So what you see with eliminative materialism is this dogmatic insistence that the objective view of modern science is complete in principle, if not in detail. Whatever ‘consciousness’ is, it must be something which can be accommodated inside this schema, otherwise it’s reality is either illusory or deceptive. That’s their view in a nutshell. — Wayfarer

The solution, as I see it, is to put qualities like color, etc., back in the world where they belong. It is the apple that is red, there is not red qualia in people's minds, or anywhere else. We see that the apple is red because it is red. Just as we see that there is one apple because there is one apple. That is nature from our perspective (the relational interaction between ourselves and the world that we are a part of).

So what’s involved in rejecting it is retracing the steps, as it were, to how that situation arose and re-framing the whole issue. — Wayfarer

:up: -

Nothing to do with Dennett's "Quining Qualia"In these discussions, I really am at a loss to explain how the Dennet's and Churchlands of the world actually the believe the stuff they're saying. I think it has less to do with how they experience the world and more to do with a certain mindset that views consciousness (and everything associated with it) as "woo". — RogueAI

Yes, it's a conceptual dispute. Consider whether gravity is a real force (per Newton) or a fictitious force (per GR). On any theory, walking off the edge of a cliff is a bad idea. But from the perspective of GR, gravity understood as action at a distance is "woo" (it's instead local spacetime curvature).

Similarly stubbing your toe is going to hurt, regardless of your theory. But conceptually, qualia for a non-dualist is like a real force of gravity (action at a distance) is for a modern physicist. It's a ghostly entity with no real role to play in one's theory.

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum