-

Michael

16.8kDo we perceive the intermediaries or the distal stimulus? The intermediaries are part of the "mechanics of perception"; they are not the perceived object. — Luke

Michael

16.8kDo we perceive the intermediaries or the distal stimulus? The intermediaries are part of the "mechanics of perception"; they are not the perceived object. — Luke

It's an ambiguous question.

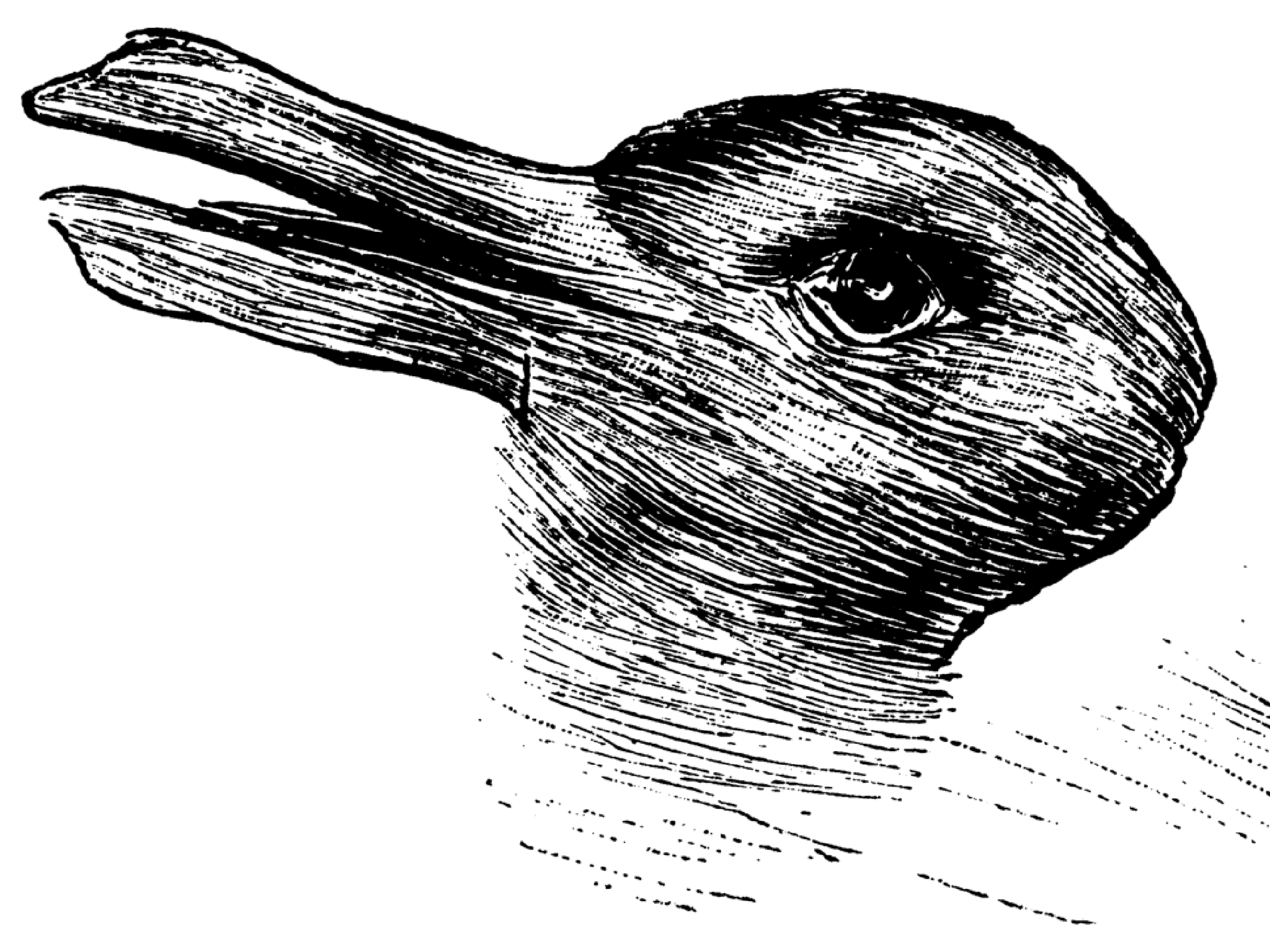

Take the duck-rabbit:

Sometimes I see a duck, sometimes I see a rabbit. A duck is not a rabbit. Therefore, is it the case that sometimes I see one distal object and sometimes I see another? No; the distal object is the same.

In this context "seeing a rabbit" and "seeing a duck" has less to do with the distal object and more to do with my brain's interpretation of the sensory input.

Take also the dress:

Some see a white and gold dress, some see a black and blue dress. A white and gold dress is not a black and blue dress. Therefore, there is a very meaningful sense in which what one group sees isn't what the other groups sees, even though the same distal object is involved (assuming that they're looking at the same computer screen).

This is why I think arguing over the grammar of "I see X" misses the point. The issue was always the epistemological problem of perception, which concerns the relationship between the features of phenomenal experience (colour, taste, size, distance) and the existence and properties of distal objects. -

Michael

16.8kNobody has ever thought that fire engines are red in the dark — Jamal

Michael

16.8kNobody has ever thought that fire engines are red in the dark — Jamal

See A Naïve Realist Theory of Colour and primitivism. Plenty of people thought – and probably still do, particularly if they are not taught science – that fire engines are red in the dark and that the presence of light simply "reveals" that colour. -

Michael

16.8kMaybe I wasn’t clear enough. I meant phenomenal intermediaries. — Jamal

Michael

16.8kMaybe I wasn’t clear enough. I meant phenomenal intermediaries. — Jamal

Phenomenal experience is the intermediary. The epistemological problem of perception questions the reliability of phenomenal experience in informing us of the nature of the external world. Direct realists argued that it is reliable, because phenomenal experience is the "direct presentation" of external world objects and their properties, whereas indirect realists argued that phenomenal experience is, at best, a mental representation of external world objects and their properties, and so is possibly unreliable.

At the very least we can apply modus tollens and simply say that if phenomenal experience is not reliable then these direct realists are wrong, even without having to ask what they actually mean by "direct presentation". -

Mww

5.4kI'd say there is ample evidence of perception and thinking being entangled. — wonderer1

Mww

5.4kI'd say there is ample evidence of perception and thinking being entangled. — wonderer1

And I’d agree. They are entangled insofar as they work in conjunction with each other, and that necessarily, but only for a specific end, re: experience or possible experience. But to be entangled with each other in a system is not the same as mingled with each other, which is implied by saying perception contains both sensation and cognition. -

frank

18.9kPhenomenal experience is the intermediary — Michael

frank

18.9kPhenomenal experience is the intermediary — Michael

I think the very idea of an intermediary is a red herring. What's really at stake is whether phenomenal experience alone informs us about the world around us. It very clearly does not.

Ever since we discovered the anatomy of sensory apparatus, the only way to argue for direct realism is to equivocate. -

Michael

16.8kI think the very idea of an intermediary is a red herring. — frank

Michael

16.8kI think the very idea of an intermediary is a red herring. — frank

Yes, perhaps. I meant it as an intermediary between the "thinking" aspect of consciousness (that interprets and makes use of phenomenal experience) and the external world.

So perhaps it is more accurate to say that we are directly cognizant of phenomenal experience and through that indirectly cognizant of distal objects. -

frank

18.9kYes, perhaps. I meant it as an intermediary between the "thinking" aspect of consciousness (that interprets and makes use of phenomenal experience) and the external world.

frank

18.9kYes, perhaps. I meant it as an intermediary between the "thinking" aspect of consciousness (that interprets and makes use of phenomenal experience) and the external world.

So perhaps it is more accurate to say that we are directly cognisant of phenomenal experience and through that indirect cognizant of distal objects. — Michael

I think that about sums up the prevailing outlook of our time. I lean toward the notion that all three: the phenomenal, the conceptual (by which we make sense of the flood of incoming data), and the Big Kahuna: the self, are all products of analysis, where we draw back from experience and pick it apart. In the midst of living experience I think those three are kind of fused. -

Luke

2.7kSometimes I see a rabbit, sometimes I see a duck. A duck is not a rabbit. Therefore, is it the case that sometimes I see one distal object and sometimes I see another? No; the distal object is the same. — Michael

Luke

2.7kSometimes I see a rabbit, sometimes I see a duck. A duck is not a rabbit. Therefore, is it the case that sometimes I see one distal object and sometimes I see another? No; the distal object is the same. — Michael

I agree, and that's the point.

In this context "seeing a rabbit" and "seeing a duck" has less to do with the distal object and more to do with my brain's interpretation of the sensory input. — Michael

Your interpretation (the intermediary) is either part of the perception, or else it occurs after the perception. Either way, your interpretation (the intermediary) is not the perceived distal object. In other words, the intermediary (your interpretation) is not the object that is perceived. Your perception is of the distal object. GIven that both sides of this dispute are realists, the distal object is the same regardless of whether you interpret it as a rabbit or a duck. But, in order for your perception to be indirect, the intermediary (your interpretation) must be the distal object of perception.

Otherwise, it just boils down to an ambiguity in the meaning of "perceive", with one camp taking it to refer to perceiving real objects and the other camp taking it to refer to the way those objects are perceived and the contents of our phenomenal experience. The latter has little to do with realism or mind-independence. -

Michael

16.8kOtherwise, it just boils down to an ambiguity in the meaning of "perceive", with one camp taking it to refer to perceiving real objects and the other camp taking it to refer to the way those objects are perceived and the contents of our phenomenal experience. — Luke

Michael

16.8kOtherwise, it just boils down to an ambiguity in the meaning of "perceive", with one camp taking it to refer to perceiving real objects and the other camp taking it to refer to the way those objects are perceived and the contents of our phenomenal experience. — Luke

Yes, that's something that I have argued many times before, and is why I keep saying that arguing over the grammar of "I see X" misses the point entirely.

Regarding the dress, for example, there is a sense in which we all see the same thing and there is a sense in which different people see different things. When considering the sense in which different people see different things, the thing they see, by necessity, isn't the distal object (which is the same for everyone).

The relevant issue is the epistemological problem of perception; the relationship between phenomenal experience and distal objects. Distal objects are not present in phenomenal experience and the features of phenomenal experience are not the properties of distal objects. That is indirect realism to me, as contrasted with the direct realist view that distal objects are present in phenomenal experience and that the features of phenomenal experience are the properties of those distal objects. -

Michael

16.8kIn what sense are they not? — Luke

Michael

16.8kIn what sense are they not? — Luke

Phenomenal experience doesn't extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist beyond the body. Therefore, distal objects are not present in phenomenal experience.

Distal objects are a cause of phenomenal experience, but that's it.

This is even more apparent in the case of the stars we see in the night sky. Some of them have long since gone. A thing that doesn't exist cannot be present. -

Luke

2.7kPhenomenal experience doesn't extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist beyond the body. Therefore, distal objects are not present in phenomenal experience. Distal objects are a cause of phenomenal experience, but that's it. — Michael

Luke

2.7kPhenomenal experience doesn't extend beyond the body. Distal objects exist beyond the body. Therefore, distal objects are not present in phenomenal experience. Distal objects are a cause of phenomenal experience, but that's it. — Michael

If I take a photograph of a flower, then the flower is in the photograph. Distal objects are present in phenomenal experience in the same sense.

Your criterion for a direct perception seems to be that the perception must be identical with the physical object. By that standard, no perception can be direct (or a perception, for that matter). -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

In phenomenal experience, it’s crystal clear to me that when I hear spoken language, I directly hear words, questions, commands, and so on—generally, people speaking—and only indirectly if at all hear the sounds of speech as such (where “indirect” could mean something like, through the intellect or by an effort of will). Our perceptual faculties produce this phenomenal directness in response to the environment and our action in it.

Maybe an example from vision is less controversial. When you walk around a table, you don’t see it metamorphose as the shape and area of the projected light subtending your retina changes. On the contrary, you see it as constant in size and shape.

I think this is precisely where indirect realists make their hay. When you hear a foreign language you don't know, you hear sounds, not words. If you suffer some sort of brain injury and develop agnosia, you see a confusing melange of shapes and colors, not tables.

This, so their reasoning goes, the mind/brain must be creating the words, objects, etc., and this act of creation or construction then implies a relationship between perception and things that is "mediated" and in being mediated it is indirect.

And I do believe they are on to something very important and interesting here. The struggle to define how the world can possess both unity and multiplicity is as old as philosophy, as are attempts to elucidate the nature of the appearance/reality distinction. However, as you note here , these tend to end up in a confused melange.

1. Their notion of directness, seldom stated and even seldomer relevant or coherent.

Right. Where is a direct interaction in nature? They seem hard to find. If the mediation involved in perception excluded "experiencing external objects," then it seems like we also can't "drive cars," but rather merely "push pedals and turn steering wheels." We don't "turn lights on," but rather flip switches. The Sun does not heat the Earth and fuel photosynthesis, but rather its light does. Nor can water erode the ground. Rather, electrons exchange virtual photos. Hemoglobin cannot "bind oxygen," but rather this is mediated by the activity of electrons, etc.

Is these strawman comparisons? Perhaps. But determining if they are would require a firm definition of what constitutes the level of mediation at which something becomes indirect.

2. Their notions of “as it is” and “what it's really like.”

"To consider any specific fact as it is in the Absolute (in reality), consists here in nothing else than saying about it that, while it is now doubtless spoken of as something specific, yet in the Absolute, in the abstract identity A = A, there is no such thing at all, for everything is there all one." (Phenomenology of Spirit §16). The truth rests in "the night in which all cows are black."

But to my mind this sets up two problems. The first is justifying that experience is somehow "less real" than this night of in-itselfness. The second is defining the meaning of truth in a context where falsity is not a possibility. A third might be justifying the existence of "things as they really are," when it seems more appropriate to say there is just a thing (singular) as it is.

4. Their motivation: where they’re coming from is really unclear.

So, this is the most interesting case. I think the position generally comes from a simple desire for an adequate explanation of perception in most cases. But for more systematic thinkers, I believe there is often deeper motivations.

If all definiteness, the existence of cats, trees, etc., is a creation of minds, or a creation of language, then this has implications for ethics, politics, aesthetics, etc. It is a view that can support a certain flavor of humanism, since man has now become the origin point of the world as we know it and nothing, or nothing definite at least, "stands behind" him.

On the one hand, since minds and language are malleable, it suggests a sort of freedom to restructure the world in ways that might not be available otherwise. Certainly, it's also been taken as an avenue for attacking the validity of religion as well. On the other, it helps frame existentialism that is grounded on the assumption that the universe is essentially meaningless, absurd, etc. It can be a stepping off point for moral relativism or nihilism, although it isn't necessarily, nor is it the only path there. It helps for claims that knowledge is essentially power, or that power relations define the reality of the world, etc. In general, it seems to be a major route for challenging naturalism.

Your criterion for a direct perception seems to be that the perception must be identical with the physical object. By that standard, no perception can be direct.

It doesn't really work for knowledge either. Having your head turn into an apple wouldn't seem to grant you direct knowledge of being an apple. Chiseling propositions into a rock doesn't cause the rock to know those propositions.

Knowing is relational, but so are all other physical properties. No one sees blue cars without there being someone who is looking, but neither do things float in water without being placed in water, or conduct electricity in the absence of current. So that knowledge or perception require a certain sort of relation to be instantiated isn't unique.

But then smallism and reductionism would also seem to be routes to a sort of indirect realism. "Seeing red," would be a process related to a whole. However, if all facts about wholes are explainable in terms of facts about smaller parts, and we don't think molecules and light waves "see red," then "seeing red," has to turn out to be in someway illusory or indirectly related to "the way things fundementally are."

This isn't always the case. Sometimes smallism leads people to deny that anything "sees red," directly or indirectly. -

Michael

16.8kIf I take a photograph of a flower, then the flower is in the photograph. — Luke

Michael

16.8kIf I take a photograph of a flower, then the flower is in the photograph. — Luke

No it's not. The flower is on the ground. The photograph is in my pocket. The photograph is just a photosensitive material that has chemically reacted to light.

Distal objects are present in phenomenal experience in the same sense.

Which is not a direct sense. It's an indirect sense. The photograph is a representation of the flower and phenomenal experience is a representation (at least, perhaps, with respect to primary qualities) of distal objects.

By that standard, no perception can be direct. — Luke

Phenomenal experience is directly present in conscious awareness.

You really are just describing indirect realism but refusing to call it that. -

RussellA

2.6kBut of course the noumenal isn't actually said to to only act/exist in-itself, it's said to act on us, to cause. So we know it through its acts, but then this is said to not be true knowledge. How so? — Count Timothy von Icarus

RussellA

2.6kBut of course the noumenal isn't actually said to to only act/exist in-itself, it's said to act on us, to cause. So we know it through its acts, but then this is said to not be true knowledge. How so? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, on the one hand, the thing-in-itself can be quite unknowable, even though what it does can be quite knowable.

I look at an object and perceive the colour green. Something about the object has caused me to perceive the colour green.

Humans often conflate cause with effect, in that if a green object is perceived, the cause is described as a green object.

Knowledge is about what I perceive, the appearance, the phenomena, not what has caused such a perception, the unknowable thing-in-itself.

===============================================================================

There has to be a way to distinguish between fantasy and fiction, between Narnia and Canada. So, to simply say that dragons and gorillas both come from mind is to miss something that differentiates them. — Count Timothy von Icarus

For the Neutral Monist, in the mind-independent world, the dragon has the same ontological existence as the gorilla, ie, none. For the Neutral Monist, dragons and gorillas are concepts that only exist in the human mind.

We impose our concepts onto what we observe in the world, and if there is a correspondence between our concept and what we observe in the world, we say that the subject of the concept exists in the world.

Therefore, we define fantasy as a concept that we have not yet observed to exist in the world and fact as a concept that we have observed to exist in the world.

However, the fact that we have never observed a dragon in the world is not proof that dragons don't exist in the world, it's only proof that we have never observed one.

===============================================================================

Is the claim that something only has "ontological existence" if it is "mind independent?" Wouldn't everything that exists have ontological existence? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, even though the thought of beauty only exists in the mind, the fact that the thought exists means that is has an ontological existence. The exact nature of its ontological existence is as of today a mystery.

Within the world, part is mind and part mind-independent. It may well be that panprotopsychism is correct, and the part that is mind is no different to the part that is mind-independent. In this event, separating the world into mind and mind-independent is just a linguistic convenience.

===============================================================================

So the concept cat only has to do with humans and nothing outside them? I just don't find this plausible. This would seem to lead to an all encompassing anti-realism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Each life form having a mind, whether human or cat, can only have direct knowledge of what is in its own mind, though can presumably reason about what it has perceived

This is compatible with Anti-Realism, where an external reality is reasoned about rather than being directly known about.

From the Wikipedia article on Anti-realism

In anti-realism, the truth of a statement rests on its demonstrability through internal logic mechanisms, such as the context principle or intuitionistic logic, in direct opposition to the realist notion that the truth of a statement rests on its correspondence to an external, independent reality. In anti-realism, this external reality is hypothetical and is not assumed.

As life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years, I am sure that as humans have the concept of cats, cats also have the concept of cats. I believe that cats have the concept of cats, but I don't know, as I have no telepathic ability. But then again, I don't know that other people have the same concept of cats as I do for the same problem of telepathy.

The notion of cat can refer to either the word "cat" or the concept cat. If referring to the word "cat" then this is specific to English speakers, but if referring to the concept cat, then this may be common across different languages and different life forms

However, this raises the problem of the indeterminacy of translation, in that "cat" in English may not mean the same as "chat" in French.

From the IEP article The Indeterminacy of Translation and Radical Interpretation

It is true that, in the case of translation too, we have the problem of underdetermination since the translation of the native’s sentences is underdetermined by all possible observations of the native’s verbal behaviour so that there will always remain rival translations which are compatible with such a set of evidence.

It also raises the problem as how a cat knows the concept of cat without a language having the word "cat" as part of it, taking us back to Wittgenstein's Private language problem.

===============================================================================

Wittgenstein pointed out that if language is defined as something used to communicate between two or more people, then, by that definition, you can't have a language that is, in principle, impossible to communicate to other people. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't think Wittgenstein's Private Language Argument was about definitions

Wittgenstein argued that a Private Language is impossible

From the SEP article Private Language

In §243 of his book Philosophical Investigations explained it thus: “The words of this language are to refer to what only the speaker can know — to his immediate private sensations. So another person cannot understand the language.” ............Wittgenstein goes on to argue that there cannot be such a language. -

Luke

2.7kNo it's not. The flower is on the ground. The photograph is in my pocket. The photograph is just a photosensitive material that has chemically reacted to light. — Michael

Luke

2.7kNo it's not. The flower is on the ground. The photograph is in my pocket. The photograph is just a photosensitive material that has chemically reacted to light. — Michael

You must have a lot of difficulty with captchas when they ask you to choose all the photos with buses or traffic lights in them, since your answer must always be none.

Distal objects are present in phenomenal experience in the same sense.

Which is not a direct sense. It's an indirect sense. — Michael

A direct perception is not when the perception and the physical object are identical. Perception concerns receiving information about one's physical environment via the senses, not receiving large physical objects via the senses.

You really are just describing indirect realism but refusing to call it that. — Michael

You aren't talking about the sensory perception of mind-independent objects if you think that a direct perception requires a phenomenal experience to be identical with a distal object. -

Michael

16.8k

Michael

16.8k

Let's take the SEP article.

Direct Realist Presentation: perceptual experiences are direct perceptual presentations of ordinary objects.

...

Direct Realist Character: the phenomenal character of experience is determined, at least partly, by the direct presentation of ordinary objects.

...

On [the naive realist] conception of experience, when one is veridically perceiving the objects of perception are constituents of the experiential episode. The given event could not have occurred without these entities existing and being constituents of it; in turn, one could not have had such a kind of event without there being relevant candidate objects of perception to be apprehended. So, even if those objects are implicated in the causes of the experience, they also figure non-causally as essential constituents of it... Mere presence of a candidate object will not be sufficient for the perceiving of it, that is true, but its absence is sufficient for the non-occurrence of such an event. The connection here is [one] of a constitutive or essential condition of a kind of event.

Perhaps you could explain how to properly interpret the parts in bold.

Under any ordinary reading, the flower is not "directly presented in" or "a constituent of" the photo. The photo is just a photosensitive surface that has chemically reacted to light.

And by the same token, the flower is not "directly presented in" or "a constituent of" phenomenal experience. Phenomenal experience is just a mental phenomenon elicited in response to signals sent by the body's sense receptors.

So given the above account of direct/naive realism, direct/naive realism is false. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI have basically less than zero sympathy for the positions of Michael, @hypericin and their ilk. I’m aware there are still some philosophers around who tend to kind of agree with them, and I know that there do exist non-stupid ways of arguing for indirect realism. Even so, the position seems really weird to me. What I have the most trouble with are four things:

Leontiskos

5.6kI have basically less than zero sympathy for the positions of Michael, @hypericin and their ilk. I’m aware there are still some philosophers around who tend to kind of agree with them, and I know that there do exist non-stupid ways of arguing for indirect realism. Even so, the position seems really weird to me. What I have the most trouble with are four things:

1. Their notion of directness, seldom stated and even seldomer relevant or coherent.

2. Their notions of “as it is” and “what it's really like.”

3. Their constant appeals to science, which are bewildering.

4. Their motivation: where they’re coming from is really unclear. — Jamal

Good post. I agree. And the distinction between physical and phenomenal mediation is useful.

This quote seems to identify the method, which is a kind of reactionary rejection:

At the very least we can apply modus tollens and simply say that if phenomenal experience is not reliable then these direct realists are wrong, even without having to ask what they actually mean by "direct presentation". — Michael

It is something like the adherence to an extreme based on the rejection of the opposite extreme. This is possible because there are a number of different indirect and direct realisms on offer, and thus one can reject an implausible form of direct realism and declare oneself an indirect realist.

's point about the "homunculus" still seems appropriate. The idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. Of course there are ways in which reason can (and does) correct for perceptual distortions, but I don't find the schizophrenic separation that accompanies indirect realism tenable. -

Michael

16.8kThe idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. — Leontiskos

Michael

16.8kThe idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. — Leontiskos

There is. There's rational interpretation. There's the "thinking" self. See the duck-rabbit above. Sometimes I see a rabbit, sometimes I see a duck, even though nothing about the phenomenal experience has changed.

Much like a homunculus isn't required for self-reflection, a homunculus isn't required for indirect perception. -

Leontiskos

5.6kThere is. There's rational interpretation. — Michael

Leontiskos

5.6kThere is. There's rational interpretation. — Michael

Hence the sentence that followed the one you quoted. -

Michael

16.8kSo, even if [1] those objects are implicated in the causes of the experience, [2] they also figure non-causally as essential constituents of it — SEP

Michael

16.8kSo, even if [1] those objects are implicated in the causes of the experience, [2] they also figure non-causally as essential constituents of it — SEP

This is the important part.

Indirect realists agree with [1] but disagree with [2], and if [2] is false then the epistemological problem of perception remains. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Under any ordinary reading, the flower is not "directly presented in" or "a constituent of" the photo. The photo is just a photosensitive surface that has chemically reacted to light.

I'll share my favorite phenomenology-based explanation:

A curious kind of identity occurs in pictures. A picture does not simply present something that looks like the thing depicted. The thing pictured is not just similar to the thing itself. It is identically and individually the same, not just similar. Suppose I have a picture of Dwight D. Eisenhower on my desk. The figure in the picture is Dwight Eisenhower himself (as pictured). It is not merely similar to Eisenhower, as his brother or son, or someone else from Kansas who happens to look like him might be. Dwight Eisenhower’s brother is similar to him, but he is not a picture of him. Similarity alone does not make something a picture. Picturing involves individual identity, not just similarity

But, you may say, the picture really is not Dwight Eisenhower; he has been dead for many a year. The picture is really only a piece of paper. Of course, the two are different entities, different substances;but when we take them that way, we are not taking them as picture and pictured. We are taking them just as things. Once we get into the logic of pictures and appearances, something else happens, and we have to report the phenomenon as it is, not as we would wish it to be. In the metaphysics of picturing, in the metaphysics of this kind of appearance, the thing pictured and Dwight Eisenhower are identically the same. The picture presents or represents that man; it does not present something just similar to him.

We should also note that the picturing relationship is one-sided. The photograph pictures Eisenhower, but Eisenhower does not picture the photograph. This is another way in which picturing differs from mere similarity, which is a reciprocal relationship. If Dwight Eisenhower’s brother is similar to him, he also is similar to his brother, but Eisenhower is not a picture of his image. Why not? I cannot give you a reason, but I know that it could not be otherwise. Neither can I give you a reason why things have predicates, but I know that they do have them when they are spoken about. Such necessities are involved in the metaphysics of appearance.

We should also note that picturing is an exhibition of intelligence or reason. To depict something is not just to copy it but to identify it and to think about it. It does not just make the thing present; it also brings out what that thing is.

Robert Sokolowski - Phenomenology of the Human Person

Sokolowski's real focus in thought and language though, not perception. He goes on to elucidate how names, words, and syntax, are used intersubjectively to present the intelligibility of objects. Roughly speaking, the intelligibility of an object is exactly what we can truthfully say about it, what can be unfolded through the entire history of "the human conversation."

But, if I find Sokolowski's use of phenomenology, particularly Husserl, and philosophy of language very useful for avoiding dicey metaphysical issues, it nonetheless feels frustratingly incomplete.

Here, I think Nathan Lyons is more helpful, even if he has to go further out on a limb. At the very least, his explanation goes with the intuition that causation does not work in a sui generis manner when it comes to perceiving subjects.

[The] particular expression of intentional existence—intentional species existing in a material medium between cogniser and cognised thing— will be our focus...

In order to retrieve this aspect of Aquinas’ thought today we must reformulate his medieval understanding of species transmission and reception in the terms of modern physics and physiology.11 On the modern picture organisms receive information from the environment in the form of what we can describe roughly as energy and chemical patterns. 12 These patterns are detected by particular senses: electromagnetic radiation = vision, mechanical energy = touch, sound waves = hearing, olfactory and gustatory chemicals = smell and taste.13 When they impinge on an appropriate sensory organ, these patterns are transformed (‘transduced’ is the technical term) into signals (neuronal ‘action potentials’) in the nervous system, and then delivered to the brain and processed. To illustrate, suppose you walk into a clearing in the bush and see a eucalyptus tree on the far side. Your perception of the eucalypt is effected by means of ambient light—that is, ambient electromagnetic energy—in the environment bouncing off the tree and taking on a new pattern of organisation. The different chemical structure of the leaves, the bark, and the sap reflect certain wavelengths of light and not others; this selective reflection modifies the structure of the energy as it bounces off the tree, and this patterned structure is perceived by your eye and brain as colour....

These energy and chemical patterns revealed by modern empirical science are the place that we should locate Aquinas’ sensory species today.14 The patterns are physical structures in physical media, but they are also the locus of intentional species, because their structure is determined by the structure of the real things that cause them. The patterns thus have a representational character in the sense that they disperse a representative form of the thing into the surrounding media. In Thomistic perception, therefore, the form of the tree does not ‘teleport’ into your mind; it is communicated through normal physical mechanisms as a pattern of physical matter and energy.

The interpretation of intentions in the medium I am suggesting here is in keeping with a number of recent readers of Aquinas who construe his notion of extra-mental species as information communicated by physical means.18 Eleonore Stump notes that ‘what Aquinas refers to as the spiritual reception of an immaterial form . . . is what we are more likely to call encoded information’, as when a street map represents a city or DNA represents a protein. 19... Gyula Klima argues that ‘for Aquinas, intentionality or aboutness is the property of any form of information carried by anything about anything’, so that ‘ordinary causal processes, besides producing their ordinary physical effects according to the ordinary laws of nature, at the same time serve to transfer information about the causes of these processes in a natural system of encoding’.22

The upshot of this reading of Aquinas is that intentional being is in play even in situations where there is not a thinking, perceiving, or even sensing subject present. The phenomenon of representation which is characteristic of knowledge can thus occur in any physical media and between any existing thing, including inanimate things, because for Aquinas the domain of the intentional is not limited to mind or even to life, but includes to some degree even inanimate corporeality.

This interpretation of intentions in the medium in terms of information can be reformulated in terms of the semiotics we have retrieved from Aquinas, Cusa, and Poinsot to produce an account of signs in the medium. On this analysis, Aquinas’ intentions in the medium, which are embeded chemical patterns diffused through environments, are signs. More precisely, these patterns are sign-vehicles that refer to signifieds, namely the real things (like eucalyptus trees) that have patterned the sign-vehicles in ways that reflect their physical form.24 It is through these semiotic patterns that the form of real things is communicated intentionally through inanimate media. This is the way that we can understand, for example, Cusa’s observation that if sensation is to occur ‘between the perceptible object and the senses there must be a medium through which the object can replicate a form [speciem] of itself, or a sign [signum] of itself ’ (Comp. 4.8). This process of sensory semiosis proceeds on my analysis through the intentional replication of real things in energy and chemical sign-patterns, which are dispersed around the inanimate media of physical environments

-

Michael

16.8kSokolowski's real focus in thought and language though, not perception. He goes on to elucidate how names, words, and syntax, are used intersubjectively to present the intelligibility of objects. Roughly speaking, the intelligibility of an object is exactly what we can truthfully say about it, what can be unfolded through the entire history of "the human conversation." — Count Timothy von Icarus

Michael

16.8kSokolowski's real focus in thought and language though, not perception. He goes on to elucidate how names, words, and syntax, are used intersubjectively to present the intelligibility of objects. Roughly speaking, the intelligibility of an object is exactly what we can truthfully say about it, what can be unfolded through the entire history of "the human conversation." — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that's the sort of approach that many here are taking when they claim to be direct realists, even though whatever they're saying has nothing to do with the actual mechanics of perception, the relationship between perceptual experience and distal objects, or the epistemological implications thereof.

Howard Robinson calls this the retreat from phenomenological direct realism to semantic direct realism, and argues that semantic direct realism is consistent with indirect realisms like the sense-datum theory.

The patterns thus have a representational character in the sense that they disperse a representative form of the thing into the surrounding media. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think the notion that they are representational is questionable. Phenylthiocarbamide is a chemical that some taste as bitter and some don't. For the sake of argument, let's assume that some taste it as sour. Which of "sourness" and "bitterness" is a representation of phenylthiocarbamide? Does it make sense to suggest that either is a representation? I think it makes much more sense to simply say that each is just an effect given the particulars of the eater's bodies.

Or perhaps "representation" is something that only works in the case of visual geometry? I think my thought experiment here brings even that into question. I don't think there's reason to treat sight as fundamentally different to any other mode of experience. -

RussellA

2.6kThe idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. — Leontiskos

RussellA

2.6kThe idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. — Leontiskos

For the Indirect Realist, inferences about the world are made based on phenomenal experiences, in that I see a red dot and infer that it was caused by the planet Mars.

For the Direct Realist also, when seeing a red dot, the inference is made that it was caused by the planet Mars.

For both the Indirect and Direct Realist, the world can only be inferred from their phenomenal experiences.

In what sense is inferred knowledge direct knowledge? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

In what sense is inferred knowledge direct knowledge?

If "direct knowledge" is aphenomenal knowledge, it wouldn't seem to make sense as a concept. So I think the disagreement is about the relevance of the adjective. If knowledge only exists phenomenally, calling phenomenal knowledge indirect would be like saying we only experience indirect pain, because we don't experience the "in-itselfness" of damage to our bodies. There doesn't seem to be a real direct/indirect distinction.

But I think there is perhaps a more compelling metaphysical objection here. We wouldn't tend to say that "we can only indirectly throw baseballs because, in reality, it is always our arm that does the throwing." That wouldn't make sense because our arm is part of us. So when our arm throws a ball, we throw the ball.

Likewise, minds are part of the world. So, sans dualism, a mind perceiving something is the world perceiving itself. If brains and sense organs perceive, and they are part of the world, wherein lies the separation that makes the relationship between brains and the world indirect? How is it different from other physical processes?

The obvious answer is that in one type of process, there is phenomenal awareness. But we can't define what it means for an interaction to be "indirect" in terms of phenomenological awareness, because that just begs the question by saying that phenomenal = indirect.

And I think this is where demands to define "indirect" in terms of physical interactions becomes relevant. Perhaps there is some way to demarcate direct and indirect physical processes, although I am skeptical of this.

So, humoncular regress concerns aside, I think there is a more general concern that the "indirect" term is smuggling dualism in. -

frank

18.9kI think there is a more general concern that the "indirect" term is smuggling dualism in. — Count Timothy von Icarus

frank

18.9kI think there is a more general concern that the "indirect" term is smuggling dualism in. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You tend to do these oblique attacks instead of swapping argument for argument. I'd rather you set out why indirect realism is necessarily dualist (property dualism? substance dualism?) rather than imply it as a concern. Maybe it's just a difference in style. -

Michael

16.8kAnd I think this is where demands to define "indirect" in terms of physical interactions becomes relevant. Perhaps there is some way to demarcate direct and indirect physical processes, although I am skeptical of this. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Michael

16.8kAnd I think this is where demands to define "indirect" in terms of physical interactions becomes relevant. Perhaps there is some way to demarcate direct and indirect physical processes, although I am skeptical of this. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Using the examples from the SEP article, we can say that the experience of a distal object is direct iff the distal object is a constituent of the experience.

If we then say that indirect realism is the rejection of direct realism, we can say that the experience of a distal object is indirect iff the distal object is not a constituent of the experience.

Does the science of perception agree with or disagree with the claim that distal objects are constituents of experience? I think it disagrees with it. It certainly shows a causal connection, but nothing more substantive.

Direct realism would seem to require a rejection of scientific realism, perhaps in favour of scientific instrumentalism, allowing for something like colour primitivism and for experience to extend beyond the body, both of which are probably what was believed by the direct realists of old (and which is my uncritical, intuitive view of the world in everyday life). -

Leontiskos

5.6kThis is the important part. — Michael

Leontiskos

5.6kThis is the important part. — Michael

Can you cite your source?

...if [2] is false then the epistemological problem of perception remains. — Michael

The "epistemological problem of perception." That phrase may capture the problem. As I see it the realism dispute is an epistemological dispute, and folks around here are focusing too strongly on perception at the expense of epistemology. Of course epistemological theories incorporate sense perception in one way or another, but to speak about sense perception apart from broader epistemological considerations is myopic at best. After all, we're not all Humeans.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum