-

Janus

17.9kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal onjects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction.

Janus

17.9kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal onjects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction.

There is no fact of the matter as to whether perception is direct or indirect, they are just different ways of talking and neither of them particularly interesting or useful. I'm astounded that this thread has continued so long with what amounts to "yes it is" and "no it isn't". -

creativesoul

12.2kWhat defines them as being indirect realists is in believing that we have direct knowledge only of a mental representation. — Michael

The heater grate to my right is not a mental representation. It is a distal object. It's made of metal. It has a certain shape. It consists of approximately 360 rectangle shaped spaces between 48 structural members. The spacing is equally distributed left to right as well as top to bottom. However, the left to right spacing is not the same as the top to bottom.

The 'mental representation', whatever that may refer to, cannot be anywhere beyond the body.

According to you, all we have direct access to and thus direct knowledge about is mental representations.

Where is the heater grate?

The irony of the "bewitchment" allusion... -

creativesoul

12.2kWe have names for all the different parts of biological machinery that facilitates our perception of grates.

Light directly enters the eye. The grate in the floor does not. By virtue of the light, the grate, and our biology, we directly perceive the grate. The surface of the grate directly touches the skin. By virtue of our skin, and the grate, we directly perceive the grate. The hot coffee directly touches our mouth parts. By virtue of our skin, our gustatory structures, and the hot coffee, we directly taste the coffee. The cake directly enters our nose, albeit in very small molecular form. By virtue of the cake, the air, and our noses, we directly smell the cake.

It seems that that argument against direct perception amounts to a notion of "direct perception" that cannot include complex biological machinery like ours.

It's like the opponents(arguing for indirect perception) are offering naive realism(like the eyes function like a window to the world) or nothing. -

Pierre-Normand

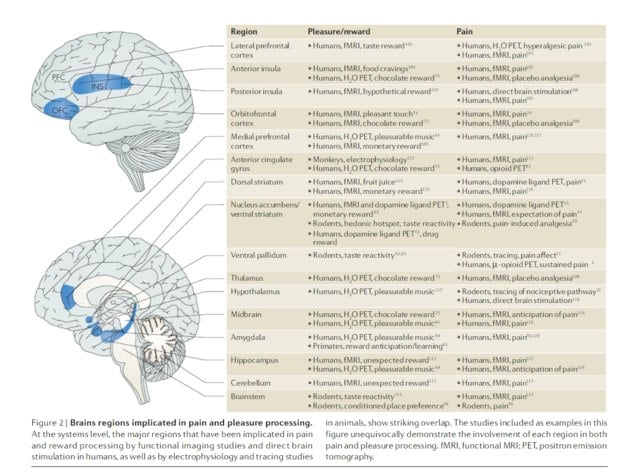

2.9kFrom a common neurobiology for pain and pleasure: — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kFrom a common neurobiology for pain and pleasure: — Michael

I appreciate you sharing this figure from the Leknes and Tracey paper. However, I think a closer look at the paper's main thesis and arguments suggests a somewhat different perspective on the nature of pain and pleasure than the one you're proposing. The key point to note is that the authors emphasize the extensive overlap and interaction between brain regions involved in processing pain and pleasure at the systems level. Rather than identifying specific areas where pain or pleasure are "felt," the paper highlights the complex interplay of multiple brain regions in shaping these experiences.

Moreover, the authors stress the importance of various contextual factors - sensory, homeostatic, cultural, etc. - in determining the subjective meaning or utility of pain and pleasure for the individual. This suggests that the phenomenology of pain and pleasure is not a raw sensory input, but a processed and interpreted experience that reflects the organism's overall state and situation.

This is rather similar to the way in which we had discussed the integration of vestibular signals with visual signals to generate the phenomenology of the orientation (up-down) of a visual scene and how this phenomenology also informs (and is informed by) the subject's perception of their own bodily orientation in the world.

Here are two relevant passages from the paper:

"Consistent with the idea that a common currency of emotion(6) enables the comparison of pain and pleasure in the brain, the evidence reviewed here points to there being extensive overlap in the neural circuitry and chemistry of pain and pleasure processing at the systems level. This article summarizes current research on pain–pleasure interactions and the consequences for human behaviour."

"Sometimes it seems that overcoming a small amount of pain might even enhance the pleasure, as reflected perhaps by the common expression ‘no pain, no gain’ or the pleasure of eating hot curries. Pain–pleasure dilemmas abound in social environments, and culture-specific moral systems, such as religions, are often used to guide the balance between seeking pleasure and avoiding pain (BOX 2). The subjective utility — or ‘meaning’ — of pain or pleasure for the individual is determined by sensory, homeostatic, cultural and other factors that, when combined, bias the hedonic experience of pain or pleasure."

The discussion of alliesthesia in the Cabanac paper cited by the authors in their note (6), and that they take inspiration from, is particularly relevant. The fact that the same stimulus can be experienced as pleasurable or painful depending on the organism's systemic conditions (e.g., hunger, thirst, temperature) highlights the dynamic and context-dependent nature of these experiences. It's not just a matter of which brain regions are activated, but how that activity is integrated in light of the organism's current needs and goals.

Furthermore, what the authors call the subjective utility or meaning of pain or pleasure corresponds to what we had agreed is the already "processed" phenomenology of experience, and not the deliveries of sense organs to the brain. There is no specific place in the brain where the final judgement is delivered regarding the final valence of the perceived situation (or sensed bodily stimulation). The final judgement about the nature of the sensation or feeling is expressed in the behavior, including self reports, of the whole embodied organism, and this is indeed where the researcher's operational criteria find it.

In this light, the idea that specific brain regions are "feeling" pain or pleasure in isolation seems to reflect a kind of category mistake. It conflates the neural correlates or mechanisms of pain with the subjective experience itself, and it attributes that experience to a part of the organism rather than the whole. The systems-level perspective emphasized by the authors is crucial. By highlighting the role of context, meaning, and embodiment in shaping the experience of pain and pleasure, it vitiates the localizationist view suggested by a focus on specific brain regions.

Of course, none of this is to deny the importance of understanding the neural mechanisms underlying affective experience. But it suggests that we need to be cautious about making simplistic mappings between brain activity and subjective phenomenology, and to always keep in mind the broader context of the embodied organism. -

Apustimelogist

946There is no fact of the matter as to whether perception is direct or indirect, they are just different ways of talking and neither of them particularly interesting or useful. I'm astounded that this thread has continued so long with what amounts to "yes it is" and "no it isn't". — Janus

Apustimelogist

946There is no fact of the matter as to whether perception is direct or indirect, they are just different ways of talking and neither of them particularly interesting or useful. I'm astounded that this thread has continued so long with what amounts to "yes it is" and "no it isn't". — Janus

Amen, ha -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal objects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction. — Janus

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal objects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction. — Janus

The Harvard psychologist Edwin B. Holt, who taught J. J. Gibson and Edward C. Tolman, made the same point in 1914 regarding the performative contradiction that you noticed:

"The psychological experimenter has his apparatus of lamps, tuning forks, and chronoscope, and an observer on whose sensations he is experimenting. Now the experimenter by hypothesis (and in fact) knows his apparatus immediately, and he manipulates it; whereas the observer (according to the theory) knows only his own “sensations,” is confined, one is requested to suppose, to transactions within his skull. But after a time the two men exchange places: he who was the experimenter is now suddenly shut up within the range of his “sensations,” he has now only a “representative” knowledge of the apparatus; whereas he who was the observer forthwith enjoys a windfall of omniscience. He now has an immediate experience of everything around him, and is no longer confined to the sensation within his skull. Yet, of course, the mere exchange of activities has not altered the knowing process in either person. The representative theory has become ridiculous." — Holt, E. B. (1914), The concept of consciousness. London: George Allen & Co.

This was quoted by Alan Costall in his paper "Against Representationalism: James Gibson’s Secret Intellectual Debt to E. B. Holt", 2017 -

Michael

16.8kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal onjects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction. — Janus

Michael

16.8kThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal onjects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction. — Janus

I didn't say that we don't have reliable knowledge, only that we don't have direct perceptual knowledge. Even the direct realist must admit that many of the things we know about in science, e.g. electrons and the Big Bang, are not things that we have direct perceptual knowledge of. Is it a performative contradiction for a direct realist to use a Geiger counter?

Alternatively, we can argue like this:

If direct realism is true then scientific realism is true, and if scientific realism is true then direct realism is false. Therefore, direct realism is false.

The direct realist would have to argue that direct realism does not entail scientific realism (and reject scientific realism) or that scientific realism does not entail indirect realism. -

Michael

16.8kThe heater grate to my right is not a mental representation. It is a distal object. It's made of metal. It has a certain shape. It consists of approximately 360 rectangle shaped spaces between 48 structural members. The spacing is equally distributed left to right as well as top to bottom. However, the left to right spacing is not the same as the top to bottom.

Michael

16.8kThe heater grate to my right is not a mental representation. It is a distal object. It's made of metal. It has a certain shape. It consists of approximately 360 rectangle shaped spaces between 48 structural members. The spacing is equally distributed left to right as well as top to bottom. However, the left to right spacing is not the same as the top to bottom.

The 'mental representation', whatever that may refer to, cannot be anywhere beyond the body.

According to you, all we have direct access to and thus direct knowledge about is mental representations.

Where is the heater grate? — creativesoul

We have direct perceptual knowledge of our body's response to stimulation. We have indirect perceptual knowledge of the distal objects that play a causal role in that stimulation.

The grammar of "I experience X" is appropriate for both direct (I feel pain) and indirect (I feel the fire) perception. -

Michael

16.8kI don’t doubt the brain is involved, but clearly the toe is as well. I’m just wondering the biology of “experience”, for instance how far from the brain it extends. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.8kI don’t doubt the brain is involved, but clearly the toe is as well. I’m just wondering the biology of “experience”, for instance how far from the brain it extends. — NOS4A2

The toe is the trigger. It's where the sense receptors are. But the sense receptors are not the pain. Pain occurs when the appropriate areas of the brain are active. -

Michael

16.8k

Michael

16.8k

I may have been overly simplistic in my account but the point stands: I feel pain, pain is not a distal object/property but a mental/neurological phenomena, and so the thing that I feel is not a distal object/property but a mental/neurological phenomena. The same for smells and tastes and colours.

You can argue that this mental/neurological phenomena involves a variety of different mental/neurological processes rather than just some simple sui generis qualia, but it still admits that it is some mental/neurological phenomena that is experienced rather than some distal object/property. -

Janus

17.9kI didn't say that we don't have reliable knowledge, only that we don't have direct perceptual knowledge. — Michael

Janus

17.9kI didn't say that we don't have reliable knowledge, only that we don't have direct perceptual knowledge. — Michael

What could direct perceptual knowledge be but reliable knowledge of its objects, as opposed to (presumably) indirect (because subject to intermediate distortions) unreliable perceptual appearances? And I'm talking about the vast amount of observational data in botany, zoology, geology, chemistry and so on, not about inferred, unobservable entities and events like electrons and the Big Bang.

If direct realism is true then scientific realism is true, and if scientific realism is true then direct realism is false. Therefore, direct realism is false. — Michael

That's not correct, it's an interpretation, and one which comprises a performative contradiction to boot. In other words, there is nothing in scientific realism from which it necessarily follows that direct realism is false, in fact indirect realism cannot support its conclusions on the basis of something which it rejects from the start: namely reliable knowledge of distal objects.

And as I've said I think the whole 'direct/ indirect' parlance is flawed anyway. What is really at stake is whether or not perception yields reliable knowledge of distal objects, end of story. -

Michael

16.8kWhat could direct perceptual knowledge be but reliable knowledge of its objects, as opposed to (presumably) indirect (because subject to intermediate distortions) unreliable perceptual appearances? And I'm talking about the vast amount of observational data in botany, zoology, geology, chemistry and so on, not about inferred, unobservable entities and events like electrons and the Big Bang. — Janus

Michael

16.8kWhat could direct perceptual knowledge be but reliable knowledge of its objects, as opposed to (presumably) indirect (because subject to intermediate distortions) unreliable perceptual appearances? And I'm talking about the vast amount of observational data in botany, zoology, geology, chemistry and so on, not about inferred, unobservable entities and events like electrons and the Big Bang. — Janus

Perception of distal objects is inference. Light from the sun travels to Earth, reflects off some object's surface, stimulates the sense receptors in the eyes, triggering activity in the brain, giving rise to conscious experience (which is either reducible to or supervenient on this brain activity). There are a multitude of mental/neurological/physical processes that exist and occur between the conscious experience and the distal object.

Distal objects and their properties are inferred from the effect (conscious experience). -

Janus

17.9kAgain not true: perceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed, no need for inference. Of course, these observable properties, being perceptible properties, involve us as well as the objects, so they don't necessarily tell us anything about what the objects are in themselves (or whether the idea of objects in themselves is anything more than a dialectical opposition).

Janus

17.9kAgain not true: perceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed, no need for inference. Of course, these observable properties, being perceptible properties, involve us as well as the objects, so they don't necessarily tell us anything about what the objects are in themselves (or whether the idea of objects in themselves is anything more than a dialectical opposition). -

Michael

16.8kperceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed — Janus

Michael

16.8kperceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed — Janus

Which means what? What does it mean to be directly observed? Given that conscious experience exists within the brain and given that the properties of distal objects exist outside the brain, the properties of distal objects do not exist within conscious experience.

Which means that everything that exists within conscious experience is the intermediary of which we have direct knowledge and from which the physically distant properties of distal objects are inferred. -

Janus

17.9kAgain not true: perceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed, no need for inference. Of course, these observable properties, being perceptible properties, involve us as well as the objects, so they don't necessarily tell us anything about what the objects are in themselves (or whether the idea of objects in themselves is anything more than a dialectical opposition).

Janus

17.9kAgain not true: perceptible properties of distal objects are directly observed, no need for inference. Of course, these observable properties, being perceptible properties, involve us as well as the objects, so they don't necessarily tell us anything about what the objects are in themselves (or whether the idea of objects in themselves is anything more than a dialectical opposition). -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

The toe is the trigger. It's where the sense receptors are. But the sense receptors are not the pain. Pain occurs when the appropriate areas of the brain are active.

When we put a brain on a table it’s impossible to say the brain feels pain or experiences, therefor it is just untrue to say brains feel pain and experience. Much more needs to be added to the equation in order for pain or experience to occur in the first place. How much more needs to be added to the equation is an important matter of debate, and would make a good thought experiment, but I wager the organism needs to be relatively complete. Organisms are so far the only objects in the universe that can be shown to feel pain and experience.

Mind or experience or whatever other spirit dualists postulate cannot occur with one single organ. So the dividing of the body into pieces and parts technique of philosophy of mind doesn’t serve us as well as it might in biology and anatomy. -

Michael

16.8kWhen we put a brain on a table it’s impossible to say the brain feels pain or experiences — NOS4A2

Michael

16.8kWhen we put a brain on a table it’s impossible to say the brain feels pain or experiences — NOS4A2

We can say anything we like.

therefor it is just untrue to say brains feel pain and experience. — NOS4A2

That's a non sequitur.

---

Of relevance is the anatomy of pain and suffering in the brain and its clinical implications:

A stimulus produces an effect on the different sensory receptors, which is being transmitted to the sensory cortex, inducing sensation (De Ridder et al., 2011). Further processing of this sensory stimulation by other brain networks such as the default mode, salience network and frontoparietal control network generates an internal representation of the outer and inner world called a percept (De Ridder et al., 2011). Perception can thus be defined as the act of interpreting and organizing a sensory stimulus to produce a meaningful experience of the world and of oneself (De Ridder et al., 2011).

...

Pain is processed by three separable but interacting networks, each encoding a different pain characteristic. The lateral pathway, with as main hub the somatosensory cortex is responsible predominantly for painfulness. The medial pathway, with as main hubs the rdACC and insula are involved in the suffering component, and the descending pain inhibitory pathway is possibly related to the percentage of the time that the pain is present.

As I see it the science is very clearly in support of indirect realism (e.g. the first paragraph of the quote above). Any armchair philosophy that tries to defend direct realism is either contradicted by the science or has redefined the meaning of "direct perception" into meaninglessness and so is not in conflict with the actual substance of indirect realism. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

The only thing a disembodied brain can do is rot. So brains do not think or experience or perceive. Only bodies do. And the body is, conveniently, the only thing standing between your perceiver and other objects in the world.

The attempt to dismiss the rest of the body in the act of perception is clearly motivated by something other than scientific inquiry, and it would be interesting to find out what that motivation is. -

Michael

16.8kThe only thing a disembodied brain can do is rot. So brains do not think or experience or perceive. Only bodies do. And the body is, conveniently, the only thing standing between your perceiver and other objects in the world. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.8kThe only thing a disembodied brain can do is rot. So brains do not think or experience or perceive. Only bodies do. And the body is, conveniently, the only thing standing between your perceiver and other objects in the world. — NOS4A2

Bodies are required to keep brains alive and functioning, but conscious experience is to be found in the brain activity. When there's no (higher) brain activity there's no conscious experience, e.g. those in a coma or in non-REM sleep, even if the bodies respond to stimulation.

The attempt to dismiss the rest of the body in the act of perception is clearly motivated by something other than scientific inquiry, and it would be interesting to find out what that motivation is. — NOS4A2

No, it's just what the science shows. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Bodies are required to keep brains alive and functioning, but conscious experience is to be found in the brain activity. When there's no (higher) brain activity there is no consciousness, e.g. those in a coma or in non-REM sleep.

Brains are required to keep bodies alive and functioning, as well. In either case, bodies and brains grew together as one organism, one object, all of it inextricably and intimate linked together into a single object. Conscious experience, perception, or whatever other activity is impossible if one or the other is missing or deceased or uncoupled. That’s a brute fact we ought to consider, in my opinion. -

Michael

16.8kConscious experience, perception, or whatever other activity is impossible if one or the other is missing or deceased or uncoupled. That’s a brute fact we ought to consider, in my opinion. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.8kConscious experience, perception, or whatever other activity is impossible if one or the other is missing or deceased or uncoupled. That’s a brute fact we ought to consider, in my opinion. — NOS4A2

That's not at all relevant.

If my computer isn't plugged into the wall socket then it won't even start, but the operating system is to be found in the SSD, not in the wall socket.

That A depends on B isn't that B contains A. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

Computers are one thing, organisms are quite another.

It is true that organisms perceive. It is untrue that brains do. It isn’t even conceivable that brains perceive. Even the brain-in-a-vat scenario requires things external to the brain to mimic the reality of a body. -

Michael

16.8kIt is true that organisms perceive. It is untrue that brains do. — NOS4A2

Michael

16.8kIt is true that organisms perceive. It is untrue that brains do. — NOS4A2

If you define "perception" as the body responding to external stimulation then this is a truism, but this isn't at all relevant to the debate between direct and indirect realism.

We see things when we dream and hear things when we hallucinate. The things we see and hear when we dream and hallucinate are percepts – phenomena either reducible to or supervenient on brain activity – and these percepts exist when awake and not hallucinating, having been caused by the body responding to some appropriate external stimulation. Visual percepts are what the sighted have and the cortical blind lack, and this can be shown by comparing the activity in the primary visual cortex of the sighted and the cortical blind.

These percepts are the intermediary from which we infer the existence and nature of some external stimulus and/or some distal object (e.g. where the stimulus is light), given that conscious experience does not extend beyond the brain, let alone the body, and so these stimuli and distal objects do not exist within conscious experience.

This is what the science shows and this is quite clearly indirect realism. -

AmadeusD

4.2kAccording to you, all we have direct access to and thus direct knowledge about is mental representations. — creativesoul

AmadeusD

4.2kAccording to you, all we have direct access to and thus direct knowledge about is mental representations. — creativesoul

This is, patently, true. This is the crux, and the thing no one has even attempted to surmount, in their attempt to explain 'direct' realism. It then turns out that the conception is in fact, that we receive light directly from the outside of our body.

Sure. That does nothing for the competing theories. Hence, certain levels of "wtf bro". -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

I think we’re all aware of the arguments from illusion and the argument from science. Searle addresses these in his so-called "Bad Argument". Both fall prey to the fallacy of ambiguity; there is some ambiguity with the verb "see", for example. In the case of hallucination there is no object of perception. If there was, it wouldn't be a hallucination. So we're confusing the object of perception with perception itself.

The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110563436-003/html?lang=en

I don't agree with Searle's positive account of perception, all this about "intentionality" and whatnot, but we at least need to try to move the arguments forward instead of reiterating them.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum