Comments

-

Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguisticsis the statement: "a dog is a mammal" analytic? — Janus

The meanings of words can change. For example, a dog can mean a domesticated mammal or it can mean a terrible film.

If a dog means a domesticated mammal, then the statement "a dog is a mammal" is analytic, whereas, if a dog means a terrible film, then the statement "a dog is a mammal" is not analytic.

IE, even though the same word may have different meanings, it is still possible for some statements, such as "a dog is a mammal" to be analytic.

Can analytic statements be ambiguous? — Janus

The Merriam Webster defines analytic as "being a proposition (such as "no bachelor is married") whose truth is evident from the meaning of the words it contains". The Cambridge dictionary defines analytic as "(of a statement) true only because of the meanings of the words, without referring to facts or experience"

There is some ambiguity between these definitions of analytic

IE, even though the definition of analytic may be ambiguous, given a particular definition, the analytic expression itself cannot be ambiguous. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSo, would "The Eiffel Tower is located in France" still be be meaningful if all of humanity were suddenly wiped out, but it could not be true or false because no one would know it's meaning, or would it no longer be meaningful at all? — creativesoul

Consider "ya mnara lipo nchi". This object has no meaning until some one gives it a meaning. If there is no one to give it a meaning, it cannot have a meaning. As with a pebble, which is neither true not false, if "ya mnara lipo nchi" has no meaning, it cannot be either true or false. Similarly with "The Eiffel Tower is located in France".

Therefore, both will be true. As there would be no one around, i) it could not be true or false because no one would know it's meaning and ii) it would no longer be meaningful. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsMetaphor? Can you explain? — schopenhauer1

It could be argued that any understanding we have is metaphorical. Some theorists have suggested that metaphors are not merely stylistic, but that they are cognitively important as well. In Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that metaphors are pervasive in everyday life, not just in language, but also in thought and action. Cognitive linguists emphasize that metaphors serve to facilitate the understanding of one's conceptual domain, typically an abstraction such as "life", "theories" or "ideas" through expressions that relate to another, more familiar conceptual domain, typically more concrete, such as "journey", "buildings" or "food".

For example, metaphors are commonly used in science, such as: evolution by natural selection, F = ma, the wave theory of light, DNA is the code of life, the genome is the book of life, gravity, dendritic branches, Maxwell's Demon, Schrödinger’s cat, Einstein’s twins, greenhouse gas, the battle against cancer, faith in a hypothesis, the miracle of consciousness, the gift of understanding, the laws of physics, the language of mathematics, deserving an effective mathematics, etc.

For example, within your own post one could say that the following are more metaphorical than literal: tricky, one can argue, created, one step beyond, primitive, indexed, tokenized, notion, abstractions, instantiations, riffing, idea, intermediary, analytic, reflection, externalization of the internal.

I observe something in the world that is round, but the Nominalist and Conceptualist would argue that roundness doesn't exist in the world, only in the mind. They would say that what I actually observe is one particular instantiation of roundness. In fact, nothing in the world can be exactly round, the most would be an approximation of roundness.

It is still the case, however, that I observe something round, even though no round thing can exist in the world. Therefore, the roundness that I am observing can only exist in the mind as an abstraction, as a concept. Merriam Webster lists abstraction as a synonym for concept.

I can name my concept of roundness as "round" and make the statement "I see a round ball", knowing that what I am referring to doesn't actually exist in the world but only in my mind. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsWould "The Eiffel Tower is located in France" be true if all of humanity were suddenly wiped out? — creativesoul

Is "ya mnara lipo nchi" true if there is no one who knows what it means. If no one knows its meaning, then it isn't a language, it's an object like a pebble, and as a pebble cannot be true or false.

Similarly, "the Eiffel Tower is located in France" would no longer be a language, it would become an object, and just like a pebble, cannot be considered as either true or false. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsAre primitive concepts concepts, or are they just primitive epistemological tools? — schopenhauer1

I think of concepts more as a metaphor than a literal physical thing. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsMy point being that, the very fact of such mechanisms discounts convention-only theories of language acquisition...Thus, nativists and empiricists are both right. — schopenhauer1

I totally agree. I understand certain primitive concepts as innate, such as the colour red, pain , etc. We then use these primitive concepts to build complex concepts based on our observations of the world, such as governments, mountains, etc.

Without the foundation of primitive concepts, the building of complex concepts would fall down. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsWould the thing that we've named the "Eiffel Tower" be located in the place that we've named "Paris" if all of humanity were suddenly wiped out? — creativesoul

Yes.

We observe something in the world and then name it "The Eiffel Tower". This something existed before we named it. As this something existed before being named, its existence doesn't depend on being named.

Similarly, we observe somewhere in the world and then name it "Paris". This somewhere existed before we named it. As this somewhere existed before being named, its existence doesn't depend on being named.

As both the something that has been named "The Eiffel Tower" and the somewhere that has been named "Paris" can exist without a name, they can continue to exist even if there was no one around to name them. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsRussellA seems to have avoided this conclusion by enlarging the notion of innate concepts to include everything, at least up to carburettors. — Banno

I limit innate concepts to primitive concepts, such as the colour red, pain, simple relationships such as to the left of, simple shapes such as a straight vertical line. Chomsky weirdly seems to extend innate concepts to carburettors.

Though I am pleased you are mixing me up with a major figure in analytic philosophy and one of the founders of the field of cognitive science.

RussellA would both eat the cake that all sentences are true by convention while keeping the cake that some sentences are true by the meaning of their terms. — Banno

All names are named by convention. It is by convention that the colour red has been named "red" rather than "sawdust", for example.

By convention, if a sentence is thought to correspond with the world it is named "true", otherwise it is named "false". For example, the sentence "the Eiffel Tower is in Paris" is true and the sentence "all unicorns live in Paris" is false. IE, some sentences are true by convention because the meaning of "true" has been agreed by convention.

Whether the statement "the Eiffel Tower is in Paris" is true or false can only be known by first knowing the meaning of its terms. IE, some sentences are true because the meaning of their terms has been agreed by convention. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguisticsit shows that the statement "a bachelor is an unmarried man" is not analytic, because it is not definitively and unambiguously true. — Janus

There seems to be three types of statements: "a bachelor is a bachelor", "a bachelor is an unmarried man" and a "bachelor is always rich".

It seems that there is general agreement that "a bachelor is a bachelor" is analytic and "a bachelor is always rich" is synthetic, though there doesn't seem to be agreement as to whether the statement "a bachelor is an unmarried man" is analytic or synthetic.

My argument that "bachelor is an unmarried man" is analytic because:

1) Before it can be decided whether "a bachelor is an unmarried man" is analytic or synthetic, the meaning of the words in the statement must be known.

2) We know that the set of words "unmarried" and "man" have been named "bachelor".

3) So knowing that the set "unmarried" and "men" has been named "bachelor", we know just by virtue of the meaning of the words alone that "bachelors are unmarried men" is an analytic statement.

Is there a flaw in my logic ? -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsIn regard to language, it prompts me to question the clean separation between the 'innate' and the 'environment' as put forward by Chomsky. — Paine

I agree that it is very difficult to put a clean break between a person and their environment. Enactivism discusses this.

There are two aspects:

First, how an object can interact with its environment is a function of its physical form. For example, a kettle in having the physical form it has cannot play music, the horse having the physical form it has cannot enjoy the subtleties in a Cormac McCarthy novel and the human in having the physical form it has can probably never understand the nature of consciousness.

Second, an object's physical form has been determined by its environment.

There is feedback between the innate and the environment. The Wikipedia article on Feedback notes:

Simple causal reasoning about a feedback system is difficult because the first system influences the second and second system influences the first, leading to a circular argument. This makes reasoning based upon cause and effect tricky, and it is necessary to analyse the system as a whole. As provided by Webster, feedback in business is the transmission of evaluative or corrective information about an action, event, or process to the original or controlling source. Karl Johan Åström and Richard M.Murray, Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsAlso, is identity ever proposed as an innate mechanism? — schopenhauer1

I see my brother enter the room and immediately leave the room. There is no doubt in my mind that I have seen my brother enter and leave the room.

There is no doubt in my mind that the person entering and leaving the room are identical.

I would suppose that the brain's ability to know that it is the same object that moves through space and time is an innate mechanism that has developed over 3.7 billion years of evolution, rather than something that needs to be learnt.

After all, when we see a snooker ball roll over a snooker table, we don't think that every second the old snooker ball disappears and a new snooker ball appears. We know without doubt that it is the same snooker ball. We know without doubt the nature of identity. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsIf I-language only refers to basically syntax (merge/compositionality) and not semantics, then indeed this would not have much to inform analyticity. — schopenhauer1

Chomsky said concepts wouldn't exist without an I-language, so, the semantic part of an I-language are its concepts.

Primitive innate concepts such as the colour red is one thing, but Chomsky weirdly argued for more complex innate concepts such as carburettors, Knowing that a carburettor is a device for mixing air and fuel means knowing the analytic fact that a carburettor is a device. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsI think I answered in the affirmative in my opening post, while relying on a theory of analytic statements that reduces them to convention. — Moliere

The SEP article The analytic/synthetic distinction writes:

“Analytic” sentences, such as “Paediatricians are doctors,” have historically been characterized as ones that are true by virtue of the meanings of their words alone and/or can be known to be so solely by knowing those meanings.

As regards the statement "bachelors are unmarried men", it is not possible to know whether it is analytic or synthetic until first knowing the meanings of the words used, in the same way that it is not possible to know whether the statement "moja ndio si ndoa mwanadamu" is analytic or synthetic until knowing the meanings of the words used.

Therefore, the first task is to know what the words mean.

You are right that naming is by convention. The set of words "man" and "unmarried" has been named "bachelor", though the set could equally well have been named "giraffe", "mountain" or "sawdust".

Therefore, even before trying to determine whether the statement "bachelors are unmarried men" is analytic or synthetic, we know that the set "unmarried" and "men" has been named by convention "bachelor".

So knowing that the set "unmarried" and "men" has been named "bachelor", we know just by virtue of the meaning of the words alone that "bachelors are unmarried men" is an analytic statement. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsNot to be pedantic, but does an unmarried man in a de facto relationship count as a bachelor, or must a bachelor live alone? — Janus

It depends on the definition of "marriage"

According to Merriam Webster, "A bachelor is an unmarried man".

But Merriam Webster goes on to say that the definition of "marriage" is changing:

The definition of the word marriage—or, more accurately, the understanding of what the institution of marriage properly consists of—continues to be highly controversial. This is not an issue to be resolved by dictionaries. Ultimately, the controversy involves cultural traditions, religious beliefs, legal rulings, and ideas about fairness and basic human rights.

In the past, "unmarried man" was defined as "a man who has not taken part in a contractual relationship with a woman recognised by the law". By this definition, an "unmarried man" includes a man living in a relationship with another person. Therefore, a bachelor may or may not be a man living in a relationship with another person.

Today, "unmarried man" may be defined as "a man who is not living in a relationship with another person". Therefore, a bachelor is a man not living in a relationship with another person.

The definition " a bachelor is an unmarried man" hasn't changed, but whether a bachelor, being a man, is or isn't living in a partnership with another person has changed. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsHume's argument was that concepts like causation are not inherent in the world but rather are products of our thought patterns or "habits of thought." However, if Hume's philosophy relies so heavily on a priori reasoning, why did Kant feel the need to refute him? — schopenhauer1

Hume is a realist about causation, in that although he believes that causation is real in the world it is unknowable. He rejects the idea that we directly know that events in the world are necessarily conjoined, as this would require a priori knowledge, but he does accept that we indirectly know about causation from the observation of constant conjunction of certain impressions across many instances.

Kant on the other hand, is also a Realist, but argued that a genuine necessary connection between events is required for their objective succession in time, and using his revolutionary conception of synthetic a priori judgments, rescues the a priori origin of the pure concepts of the understanding.

So yes, Hume rejected an a priori explanation for causation whilst Kant didn't.

But this raises the question, when patterns are observed in the world, how is the mind able to see these patterns. Is the mind's ability to see patterns innate a priori or learnt from the patterns themselves. Who is right, Chomsky's Innatism or Skinner's Empiricism.

Empiricism is a problem of circularity. If I have no innate rules, and I can only learn the rules from what I observe, then, as the Tortoise could have said to Achilles, where is the rule that tells me when I have discovered a rule. Empiricism proposes that there is something in the rule that I observe that tells me this is the rule that has to be followed, but where is the rule that tells me I have to follow it.

Kant expressed the problem of being able to gain all knowledge from observation in B5 of Critique of Pure Reason

Even without requiring such examples for the proof of the reality of pure a priori principles in our cognition, one could establish their indispensability for the possibility of experience itself, thus establish it a priori. For where would experience itself get its certainty if all rules in accordance with which it proceeds were themselves in turn always empirical, thus contingent?; a hence one could hardly allow these to count as first principles.

It is true that Hume argues we can only indirectly observe causation, and as such is not a priori, but it is also true that he does write about instinct, which is innate and a priori, as being more powerful than thought and understanding. It is perhaps this innate and a priori instinct that allows the mind to observe causation in the first place.

Hume in Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding wrote:

What, then, is the conclusion of the whole matter? A simple one; though, it must be confessed, pretty remote from the common theories of philosophy. All belief of matter of fact or real existence is derived merely from some object, present to the memory or senses, and a customary conjunction between that and some other object. Or in other words; having found, in many instances, that any two kinds of objects—flame and heat, snow and cold—have always been conjoined together; if flame or snow be presented anew to the senses, the mind is carried by custom to expect heat or cold, and to believe that such a quality does exist, and will discover itself upon a nearer approach. This belief is the necessary result of placing the mind in such circumstances. It is an operation of the soul, when we are so situated, as unavoidable as to feel the passion of love, when we receive benefits; or hatred, when we meet with injuries. All these operations are a species of natural instincts, which no reasoning or process of the thought and understanding is able either to produce or to prevent.

On the one hand, Hume argues that we only know causation from observation and not, as Kant argues, a priori, but on the other hand Hume many times refers to instinct, which is innate and a priori, and it is perhaps this innate a priori instinct that allows us to see patterns in our observations in the first place. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsWe agree analyticity is an aspect of language. — Moliere

This answers the OP, "Are there analytic statements?"

So all Brambles are Unbrimbled Tembres................................The example is meant to demonstrate how nonsense terms can come to make sense from the English grammar, rather than because of an I-language.. — Moliere

Yes, the E-language can be grammatical without making sense.

One advantage of the I-language is that every thought about a concept makes sense, in that meaning within an I-language is self-referential. IE, it is not possible to have a thought about a concept without that thought making sense, having meaning. If I think about the concept triangle, the thought is its own meaning. Unlike the E-language, it isn't necessary to go outside the I-language to find meaning.

The meaning of my concept of pain is the pain itself. As Searle wrote:

The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

The SEP article Concepts wrote that "Concepts are the building blocks of thoughts". The Wikipedia article Concepts wrote "Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs". As the dictionary explains thoughts as occurring in the mind, concepts must also also occur in the mind.

As with many words in language, such as evolution by natural selection, F = ma, the wave theory of light, DNA is the code of life, the genome is the book of life, gravity, dendritic branches, Maxwell's Demon, Schrödinger’s cat, Einstein’s twins, greenhouse gas, the battle against cancer, faith in a hypothesis, the miracle of consciousness, the gift of understanding, the laws of physics, the language of mathematics, deserving an effective mathematics, etc, the word "concept" should also be thought of as a ,metaphor, not something that has a literal physical existence.

In an E-language, meaning is extralinguistic, whereas in an I-language, meaning is the I-language itself. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsThe relationship between the learner and the environment can mean very different things. In the Skinner model, stimulus is always on one side and response the other side of events. For Vygotsky, for example, there is a dynamic where the stimulus becomes modified by changes in the learner....................This approach does not cancel the domain of the 'innate' but neither does it make it a realm where 'e-language' can be clearly separated from 'I-language'. — Paine

I agree, sentient life must evolve through interaction with the world in which it exists, which is why it has taken 3.7 billion years for life to have evolved to its current form.

From the Wikipedia article Enactivism

Sriramen argues that Enactivism provides "a rich and powerful explanatory theory for learning and being."[66] and that it is closely related to both the ideas of cognitive development of Piaget, and also the social constructivism of Vygotsky.[66]

The I-language cannot be separated from the E-language, in the same way that the subject of a painting cannot be separated from the colours and shapes of the paint used in the painting, yet both fulfil different functions. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsIt's because the I-language is not spoken that I doubt concepts are at work. We talk about concepts fairly frequently, and successfully. Freedom, Love, Democracy..............I think I'd just include concepts, as well as logic, within E-language. — Moliere

There is the I-language in the mind, and the E-language in the world.

There is the word "love" in the E-language which refers to the concept of love. The concept being referred to doesn't exist in the either the E-language or the world independent of any mind.

Where else can the concept of love exist if not in the I-language of the mind.

This sets out how to use analyticity. It's a convention -- if we interpreted "is" in a certain way, and we interpret the terms in a certain way, then it follows that A is D, analytically. It reads more like a stipulation than a feature of knowledge. — Moliere

Following on from the OP, the analytic and synthetic are aspects of language. The necessary and contingent are aspects of logic, and the a priori and a posteriori are aspects of knowledge.

Yes, analytic statements are not necessarily statements of knowledge. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsI was thinking an I-language would be anything but a concept........I'd say an I-language is public, in principle.................but the I-language would be formed from our social environment. — Moliere

If I touch a hot stove and see my hand blisters, in my I-language, I am conscious of pain and quickly remove my hand. But if my I-language was formed by my social environment rather than my innate instinct, in a different social environment on touching a hot stove and seeing my hand blister I could well be conscious of pleasure and leave my hand where it was.

But this is not something that is empirically discovered. In all societies, if someone touches a hot stove, they don't leave their hand there but quickly remove it. This suggests that their I- languages are the same, meaning that I-languages are not determined by the social environment but have been determined by innate instinct.

As Chomsky proposed, the I-language is not a “language” that is spoken at all, but is an internal, largely innate computational system in the brain that is responsible for a speaker’s linguistic competence.

We can classify statements such as the case of bachelors and unmarried men and dub them analytic. And we can also say "War is war" and know that the meaning is not analytic -- it's the "is" of predicating rather than the "is" of identity — Moliere

True, "war is war" is analytic if "is" refers to identity, and "war is war" is synthetic if "is" refers to predicating.

But also, using "is" as identity, if the set of words "A","B","C" and "D" is named "war", then the statement "war is B" is analytic, regardless of the meaning of "A", "B", "C" and "D".

Similarly, if the set of words "A" and "B" is named "bachelor", then the statement "a bachelor is B" is analytic, regardless of the meanings of "A" and "B". -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSo what about Hume or Quine's extreme empiricism (the denial of innate mechanisms at all)? Where does that fit in, and what is your analysis? — schopenhauer1

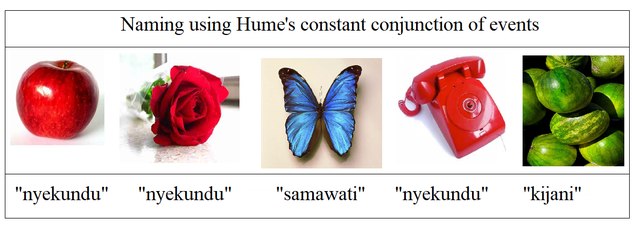

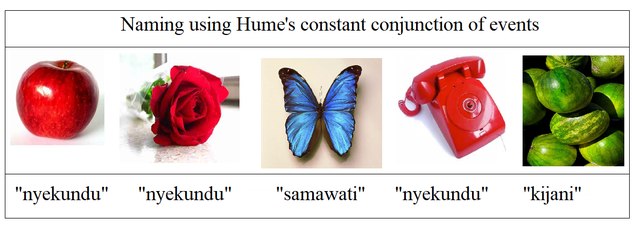

For me, the mechanism linking concepts in the mind and language in the world can be explained by Hume's principle of the constant conjunction of events, illustrated here, in Kant's terms, a posteriori. But the mind's ability to perceive patterns in the world, to perceive the constant conjunction of events is innate, a product of 3.7 billion years of life' e evolution within the world, in Kant's terms, a priori.

I'm not sure that Hume would have denied the innate. He writes in Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding:

By the term impression, then, I mean all our more lively perceptions, when we hear, or see, or feel, or love, or hate, or desire, or will. And impressions are distinguished from ideas, which are the less lively perceptions, of which we are conscious, when we reflect on any of those sensations or movements above mentioned.

It is an operation of the soul, when we are so situated, as unavoidable as to feel the passion of love, when we receive benefits; or hatred, when we meet with injuries. All these operations are a species of natural instincts, which no reasoning or process of the thought and understanding is able either to produce or to prevent.

I would assume Hume takes certain abilities as innate natural instincts, such as hearing, seeing, feeling, loving, hating, desiring and willing. It would follow that rather than learning the instinct of loving and hating from the world, we project our instincts of loving and hating onto the world.

The sort of studies done by Tomasello and such, no? But he strongly disagrees with Chomsky. He is very much of the social cognition camp — schopenhauer1

It comes down to the debate between Chomsky, who argued that language is founded on innate concepts biologically pre-set and the Behaviourists, such as Skinner, who argued that that all language is learnt during one's interaction with the environment.

There seems to be a link between Tomasello and Hume in that humans have an ability to recognize patterns.

Tomasello argued:

The essence of language is its symbolic dimension which rests on the uniquely human ability to comprehend intention. Grammar emerges as the speakers of a language create linguistic constructions out of recurring sequences of symbols. Children pick up these patterns in the buzz of words they hear around them.

Hume in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding wrote:

When we say, therefore, that one object is connected with another, we mean only, that they have acquired a connexion in our thought, and give rise to this inference, by which they become proofs of each other's existence: A conclusion, which is somewhat extraordinary; but which seems founded on sufficient evidence. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsYes I was actually going to point that out regarding the difference between "A triangle is 180 degree, three sided polygon" and "Bachelors are unmarried males". Kant may have said that the triangle is in some sense "a priori" whereas the bachelor is always a posteriori true. However, I think this distinction is muddled as there doesn't seem to be any clear distinction. — schopenhauer1

There is the E-language, whereby there are statements such as "A triangle has 80 degrees, and is a three sided polygon". The set "180 degrees, three sided and polygon" has been named "a triangle", such that the statement "a triangle is three sided" is analytic.

There is the I-language, whereby there are concepts such as a triangle has 180 degrees, is three sided and is a polygon.

I can have the concept of a triangle without knowing the word "triangle", and I can know the word "triangle" without knowing what it means, without having the concept triangle.

Though interacting with the world, my private concept of triangle is linked with the public word "triangle". By interacting with the world, my private I-language is linked with the public E-language

The Nominalist view is that abstracts don't exist in the world, only in the mind, meaning that as triangles and bachelors are concepts they only exist in the mind as abstractions.

In the sense that concepts exist in the mind as an I-language and definitions exist in the world as an E-language, I agree with Fodor that concepts cannot be definitions

I also agree with Fodor that concepts don't have an internal structure, and are, in Kant's terms, unities of apperceptions

Both the words "triangle" and "bachelor" exist in the E-language which exists in the world, whereas triangles and bachelors exist as concepts in the I-language which exists in the mind.

The next question is, how are concepts in the I-language linked with words in the E-language. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsYou want to talk about vague and muddled notions, both:

a) Chomsky's view on analyticity as described in your OP article is just that.

b) The article itself is kind of meandering and muddled touching a little of here and there — schopenhauer1

Chomsky sensibly believes that a basic range of concepts are innately represented in the human mind, because, after all, life has been evolving on Earth for about 3.7 billion years.

I would agree about some primitive concepts are innate, such as the colour red.

(1) The first one is to say that most of our concepts are definitions which are defined in terms of primitive concepts. The primitive concepts are either defined as sensory primitives such as RED, SQUARE etc., or as abstract concepts such as CAUSATION, AGENCY, and EVENT etc.

But Chomsky goes too far in arguing that some complex concepts are also innate, such as carburettor

(1) It is of course possible that Chomsky is correct that children are born with innate concepts such as: CARBURETTOR, TREE, BUREAUCRAT, RIVER, etc.; however an incredible amount of evidence is needed to support such an incredible claim.

I will take the opportunity to argue again that the statement "bachelors are unmarried men " is analytic.

Philosophers often use definitions to explain analyticity

(2) Quine suggests that one might, as is often done, appeal to definitions to explain the notion of synonymy. For instance, we might say that “bachelor” is the definition of an “unmarried man,” and thus, synonymy turns on definitions.

Quine in Two Dogmas of Empiricism attacks the analytic/synthetic distinction in large part because of the problem of substituting synonyms for synonyms

(2) However, Quine attests, in order to define “bachelor” as unmarried, the definer must possess some notion of synonymy to begin with. In fact, Quine writes, the only kind of definition that does not presuppose the notion of synonymy, is the act of ascribing an abbreviation purely conventionally. For instance, let’s say that I create a new word, ‘Archon.’ I can arbitrarily say that its abbreviation is “Ba2.” In the course of doing so, I did not have to presuppose that these two notions are “synonymous;” I merely abbreviated ‘Archon’ by convention, by stipulation. However, when I normally attempt to define a notion, for example, “bachelor,” I must think to myself something like, “Well, what does it mean to be a bachelor, particularly, what words have the same meaning as the word ‘bachelor?’” that is, what meanings are synonymous with the meaning of the word ‘bachelor?’ And thus, Quine complains: “would that all species of synonymy were as intelligible [as those created purely by convention]. For the rest, definition rests on synonymy rather than explaining it” (Quine, 1980: 26).

Quine fails to understand the function of a definition.

It is not the case that in attempting to define the notion of "bachelor", I must think to myself what does it mean to be a bachelor, and conclude that bachelor means a man that is unmarried. Rather, a definition is a set of other words, and the meaning of the words in the set plays no part in the definition. The function of the dictionary is not to explain the meaning of each word, its function is to group sets of words together and then name this set, as illustrated by @Banno here.

For example, within a language are a set words "dirisha", "mlango" and "chumba", none of which I know the meaning of, but for convenience the set may be named "nyumba". As "nyumba" names the set of words "dirisha, mlango, chumba", regardless of knowing the meaning of each word, it is necessarily known that "nyumba = chumba", ie, which is analytic.

The meaning of each word may only be discovered out with of the dictionary, external to the dictionary, for example using Hume's principle of constant conjunction of events, as illustrated here, or Wittgenstein's picture theory in the Tractatus.

As a definition is the name of a set of words, regardless of the meaning of those words, all definitions are analytic, including the definition of a "bachelor" as an "unmarried man".

1) = CHOMSKY AND QUINE ON ANALYTICITY PART 1

2) = IEP - Willard Van Orman Quine: The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSeems to me bringing vague, muddled notions of objective and subjective into the discussion can only lead to it becoming vague and muddled. — Banno

The Wikipedia article Objectivity (philosophy) notes:

In philosophy, objectivity is the concept of truth independent from individual subjectivity (bias caused by one's perception, emotions, or imagination). A proposition is considered to have objective truth when its truth conditions are met without bias caused by the mind of a sentient being.

The SEP article Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguistics notes

He sharpens this distinction in his (1986, pp. 20–2) by distinguishing what he regards as essentially the ordinary, folk notion of external, what he calls “E-languages,” such as English, Mandarin, Swahili, ASL and other languages that are commonly taken to be spoken or signed by various social groups, vs. what he regards as the theoretically more interesting notion of an internal “I-language.” This is not a “language” that is spoken at all, but is an internal, largely innate computational system in the brain (or a stable final-state of that system) that is responsible for a speaker’s linguistic competence

How can one know that within an I-language the thought that the sky is blue has an objective truth ( its truth conditions are met without bias caused by the mind of a sentient being) or a subjective truth (caused by one's perception, emotions, or imagination) without introducing the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsAgain, it seems to me you have not grasped the gist of Quine's argument — Banno

I'll keep reading.

Indeed, why take the triangle as being important? What rule was followed? And even if triangles are taken as primal, why not AME or AJK? What counts as prime depends on the task in hand. — Banno

True, language is use. Wittgenstein PI para 23 "Here the term "language-game" is meant to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life."

Elaborating, I look at parts in the world, and these parts can combine into numerous mereological wholes.

In a sense, each mereological whole exists in the world, and each may be discovered in the world, although it would take an inordinate amount of time

It is therefore true that in the world there is something with three sides which can be named "triangle", but it is also true that every possible mereological whole could also be named, again taking an inordinate amount of time

As Wittgenstein said, language is part of an activity, a form of life

As it would take too much time to discover each possible shape in the world and then decide which I had a use for, in practice, I start with a task, and then discover in the world that shape that would be suitable for the task in hand.

My judgement that a particular shape is suitable to my task at hand is based on a predetermined requirement as to the suitability of any shape, and is therefore an a priori judgement

My judgement that there is something in the world that has three sides is synthetic, as I can only know that there is something with three sides by discovery.

IE, my judgement that there exists something in the world that has three sides and has the name "triangle" has been synthetic a priori. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsThe sky is blue is synthetic a posteriori because it is discovered but true only by way of the content we pick out and not by way of how our faculties must operate. An X is NOT not X is analytic a priori as not only is it true by our faculties but the very terms don’t need to be discovered but are true immediately based on how logic operates a priori. — schopenhauer1

Using the convention of "snow is white" is true IFF snow is white, perhaps one could say:

"the sky is blue" is synthetic, the sky is blue is a posteriori, "an X is NOT not X" is analytic and an X is NOT not X is a priori.

"The sky is blue" being synthetic brings in the debate between Indirect and Direct Realism

As you wrote:

Direct realism seems to me, to posit that we "objectively" see the thing "as it is in itself". What is something "in itself" though? A tree is the tree you see as a perceiver when there is no perceiver? Mind you, I'm not saying the tree doesn't exist without a perceiver. If you answer, "Well, no the tree isn't what an average human 'sees' when observing a tree", you have your answer- and it doesn't indicate direct realism. Sense data, goes through other layers of the brain, and creates something we have called a tree. Even if you (oddly) posited just "sense data" and no other layers involved (whatever that might mean), then there is still something there as a barrier to what is the tree in itself. It is its own "indirect".

For the Direct Realist, the sky is objectively blue, in which case the statement "the sky is blue" is synthetic and refers to a world that is external to the mind.

However, for the Indirect Realist, as the sky is not objectively blue, but only subjectively blue, the statement "the sky is blue" is still synthetic but refers to a world that exists in the mind and not external to the mind. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsRight, but the key idea here is they discovered something about the concept first. — schopenhauer1

Many parts are observed in the world

But from any set of parts, numerous mereological wholes can be discovered

For example, from the 15 parts shown - thousands of possible wholes may be discovered - for example -

ACHN - BFGM - AB - ABG - etc

It is true, the observer discovers a triangle, CKO

But why discover one particular shape, rather than any of the other thousand possibilities.

Presumably, because the observer knows a priori that the triangle is a shape important in their interaction with the world.

1) Therefore, a priori, the observer knows that the triangle is a shape important in their interaction with the world.

2) It is a necessary truth that the triangle is a shape important in their interaction with the world.

3) The statement "triangles are important in their interaction with the world" is analytic, because it is known a priori that triangles are important in their interaction with the world. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsThat is to say, a triangle necessitates it being three sides in all possible worlds. However, the discovery of this truth is in some way synthetic when first discovered. The passing on of this discovery as a convention that we learn very early on, makes it "analytic", but this is only the way we discover the information. — schopenhauer1

In the beginning, someone discovered something that had three sides and it had no name. They didn't discover a "triangle", they discovered something that had three sides. The statement "triangles have three sides" would have been meaningless, as the word "triangle" didn't exist.

They named this something with three sides "a triangle", though they could equally well have named it "a circle".

Once named, as the statement "triangles have three sides" is true by virtue of the meanings of the words alone, it is therefore an analytic statement.

IE, when the statement "triangles have three sides" first occurred, it was already an analytic statement. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsNow you will not find "rown" in Merriam Webster, but we knew what she meant, as does everyone reading this. — unenlightened

Would you know what a child meant if they said something more complicated, such as

"habari za asubuhi, habari gani" without having to look in a dictionary. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSuggestions welcome. — Banno

Chomsky likes Locke.

From IEP - Locke:Epistemology

Locke defines knowledge as the perception of an agreement (or disagreement) between ideas (4.1.2). This definition of knowledge fits naturally, if not exclusively, within an account of a priori knowledge. Such knowledge relies solely on a reflection of our ideas; we can know it is true just by thinking about it. Some a priori knowledge is (what Kant would later call) analytic.

Would it be possible to get Chomsky to talk about the analytic in reference to Locke, someone he likes.

===============================================================================

An odd word, now becoming surprisingly common. What could it mean to have properties supervene onto individuals... green supervene on grass... that the green "occurs as an interruption" to the grass? Hu? And what does it relate to what I have said? — Banno

In my mind is a box that includes both the knowledge of my private experience of grass, something not available to anyone else, and the knowledge of the word "grass", which is publicly available to everyone else, as described by Wittgenstein in PI para 293.

As some philosophers, including Searle, believe in supervenience, the concept should be taken into account.

If there is no superveninece, then the word "grass" is simply the set of words "a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop".

As the SEP - The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction notes

“Analytic” sentences, such as “Paediatricians are doctors,” have historically been characterized as ones that are true by virtue of the meanings of their words alone and/or can be known to be so solely by knowing those meanings.

In this case the meaning of "grass" is fully known by knowing the meaning of the words "a typically short plant, etc". In this event, as the SEP notes, analytic.

However, if there is supervenience, then the word "grass" is more than the set of words " a typically short plant, etc". In this event, the meaning of grass cannot fully be known just by knowing the meaning of the words "a typically short plant, etc". IE, the expression cannot be analytic.

IE, whether an expression is analytic or not partly depends on one's attitude to supervenience.

===============================================================================

Why? A child knows its mother, despite not being able to provide a definition. And so on for the vast majority of words. I think you are here just wrong. — Banno

We are communicating using written language. I have no other clues to your meaning other than the words on my screen, such as tone of voice, facial expression or bodily movements.

You have written the word "mother". You may not believe me, but I don't know what this word means. Within the context of the paragraph it could mean, "a child knows its neighbourhood", "a child knows its school", "a child knows its pet", etc.

In order for me to fully understand what you are saying, what does "mother" mean ?

===============================================================================

The following argument is stolen from Austin: Look up the definition of a word in the dictionary. Then look up the definition of each of the words in that definition.Iterate. — Banno

There are two types of concepts, simple and complex (there may be better terminology).

As I wrote before

The gavagai problem may be solved by taking into account the fact that there are simple and complex concepts, and these must be treated differently. In language, first there is the naming of simple concepts, and only then can complex concepts be named, such as the complex concept "gavagai".

Simple concepts include things such as the colour red, a bitter taste, a straight line, etc, and complex concepts include things such as mountains, despair, houses, governments, etc.

Dictionaries allow us to learn complex concepts, where a complex concept is a set of simple concepts. But we cannot learn simple concepts from the dictionary

In Bertrand Russell's terms, the dictionary allows us knowledge by description but not knowledge by acquaintance.

For simple concepts, we need knowledge by acquaintance, achievable using Hume's constant conjunction of events.

===============================================================================

Is this your opinion, or your view of Chomsky, or both? — Banno

True, I should have made it clearer when I wrote " As I see it".

@Dawnstorm asked "So, if deep-structure thought (I-language thought?) can proceed without words, what stands in for words in such a situation?"

It seems inconceivable that we use words such as "road", "traffic light", "pedestrian", "blue sky" in an I-language.

As I wrote:

When driving through a busy city street, if I had to put a word to every thought or concept, I would have crashed in the first five minutes.

I see no alternative to the idea that in an I-language thoughts and concepts stand in for words.

===============================================================================

Analyticity without language? What could that be? — Banno

Starting with E-language, if "grass" has been defined as "vegetation consisting of typically short plants with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and as a fodder crop", then the statement "grass has long narrow leaves" is analytic.

There is a direct analogy between analyticity in E-language and analyticity in I-language.

Within the I-language, there are no words such as "vegetation, consisting, etc", but rather thoughts about concepts.

It follows that within the I-language, if I know that grass is vegetation consisting of typically short plants with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and as a fodder crop, then I must also know that grass has long narrow leaves, which is also analytic knowledge. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsWhen one shouts "Fire!" in, say, a theatre, one does not mean merely to refer to "the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products.".......Rather, it is a call to action in a matter of life and death. — unenlightened

True, the same word may be defined in many different ways. The Merriam Webster dictionary for "fire" lists almost 42 different uses.

Though the same principle applies, in that is is more convenient and quicker to say "fire" than "I am making a call to action in a matter of life and death." -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSuggestions welcome. — Banno

Chomsky says that concepts cannot exist without language. See Noam Chomsky on the Big Questions (Part 4).

7min "Even the simplest concepts tree desk person dog, what ever you want , even these are extremely complex in their internal structure . If such concepts had developed in proto human history when there was no language they would have been useless. They would have been an accident if developed and quickly lost as you cannot do anything with them. So the chances are very strong that the concepts developed within human history at a point where we had computational systems which satisfy the basic property"

Perhaps Chomsky would say that as concepts cannot exist without language, if there is analyticity in language then there must also be analyticity in concepts. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSo, if deep-structure thought (I-language thought?) can proceed without words, what stands in for words in such a situation? — Dawnstorm

Thoughts and concepts stand in for words

From SEP - Analayticity and Comskyan Linguistics

He sharpens this distinction in his (1986, pp. 20–2) by distinguishing what he regards as essentially the ordinary, folk notion of external, what he calls “E-languages,” such as English, Mandarin, Swahili, ASL and other languages that are commonly taken to be spoken or signed by various social groups, vs. what he regards as the theoretically more interesting notion of an internal “I-language.” This is not a “language” that is spoken at all, but is an internal, largely innate computational system in the brain (or a stable final-state of that system) that is responsible for a speaker’s linguistic competence

As I see it, in the mind there are two aspects. There are conscious thoughts about concepts, in that I can have the conscious thought that the tree is to the left of the river, and there is an underlying subconscious structure that enables me to have these conscious thoughts about concepts.

I can have conscious thoughts about concepts without the need of words. When driving through a busy city street, if I had to put a word to every thought or concept, I would have crashed in the first five minutes.

Once I can have conscious thoughts about concepts, an E-language can be developed. My conscious thought that the tree is to the left of the river may be expressed as "the tree is to the left of the river".

In a sense, our conscious thoughts about concepts is a language, but this is secondary to the underlying subconscious structure that enables thoughts about concepts. It is this underlying structure that is common to different peoples.

In an E-language, if "grass" is defined as "a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves", the statement "grass has narrow leaves" is analytic.

In the mind, if I have the thought that there is something that is typically a short plant with long, narrow leaves, then I know that this something that is typically a short plant with long, narrow leaves has narrow leaves, and again, this is analytic.

IE, in the mind, we can have conscious thoughts about concepts, but underlying this is a deeper subconscious structure that is common to different peoples that enables us to have these thoughts about concepts in the first place. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsThis is to suppose that there is a thing, which is someone's understanding of grass; as if to understand "grass" were to have a certain box in one's mind; so that your box can be different to my box. — Banno

I believe that i) grass doesn't supervene on its properties, a typically short plant, etc. and ii) "grass" doesn't supervene on its properties, "a typically short plant, etc."

To start, there is a diference between what exists in language and what exist in the world. In language, "grass" is defined by the properties "a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop". In the world, grass includes the properties a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop.

I see something in the world that has the properties typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop. It would be unwieldy in conversation to say "yesterday I mowed a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop". It is far easier to define "grass" as "a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop" in order then to more simply say "I mowed the grass"

Once "grass" has been defined as the set of properties "a typically short plant with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and used as a fodder crop". the statement "grass has narrow leaves" is true by definition and is therefore an analytic statement.

Grass in the world may have numerous properties, only some of which are included in the definition of "grass". In part for the reason that some properties may only be discovered in the future, and in part that some properties may not be useful in daily conversation. It is also true that the definition may change with time.

Definitions aren't perfect, but they are better than the alternative of not having definitions. Without definitions communication would break down. Especially if you said "I mowed the grass yesterday", and my concept of "grass" was "a thickset, usually extremely large, nearly hairless, herbivorous mammal of the family Elephantidae having a snout elongated into a muscular trunk and two incisors in the upper jaw"

As regards boxes in my mind, I agree that my concept of grass is private and inaccessible to anyone else, but my concept of "grass" is accessible to others as it is has been publicly defined.

Communication using language would break down without definitions. One consequence of definitions are analytic statements.

Analyticity is the acknowledgment that the whole doesn't supervene on its parts. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsSeeing as how the man himself is to honour us, it may be time I came to grips with this issue. — Banno

:100: Definately a worthwhile and invaluable thread.

Sure. But the point remains that not all analytic statements are acts of naming. — Banno

As the question in the OP was "If I were to ask Chomsky a question, it would be "Are there analytic statements?", does this mean that on our side we agree that there are.

But further, when do you, or I, participate in such a formal act of naming? Apart from baptisms and boat launchings, it's not something we commonly do. — Banno

True, I have never launched a boat or baptised a child, as these are things done by others having more authority than me.

But the question remains, who has determined that "triangles have three sides", and why should we accept what they say.

Presumably, it can only be because an Institution or group of people have determined that this is the case, and it would be foolhardy for me as an individual to go against forces over which I have little power.

I may never have baptised the meaning of a word, but it is only sensible to accept the meaning of a word as baptised by those more powerful than me who have come before. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsAgain, the desire to have all of language work like the very limited process of naming objects—to imagine all words referring to an object, even “meaning” or something “real”—is because we want logical necessity and predictability. — Antony Nickles

Both aspects are necessary in language.

On the one hand, we need predictability, otherwise, if you said to me "the grass is greener on the other side of the hill", and I take "grass" to mean "a large, long-necked ungulate mammal of arid country", our conversation will quickly break down. In order to establish a minimum level of agreement, reference to a dictionary will be necessary. We can then both agree that "grass" is "vegetation consisting of typically short plants with long, narrow leaves, growing wild or cultivated on lawns and pasture, and as a fodder crop"

On the other hand, no two people's understanding of "grass" will be the same, as no two people will have had the same life experiences. For example, the concept of grass to a South African taxi driver will be very different to that of an Icelandic doctor.

Communication using language, in order to work, must be founded on basic and agreed definitions of concepts, but consideration must also be taken into account that no two people's concepts of the same word will be exactly the same. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsI think this is the most interesting theory he holds, and at least prima facie, seem true. Much of language is basically self-talk. It is our thoughts to ourselves: our own reasons, moods, ideas, strategies, everything that is "discursive" in nature. — schopenhauer1

Chomsky also makes the proviso that both the visual system and language need to be stimulated from things in the external world in order to operate successfully.

See Noam Chomsky on Linguistic Theories and the Evolution of Language (Part 3) | Closer To Truth Chats.

8 min "Stimulation is necessary.............if you don't present pattern stimulation in the early days of life the visual system won't function , it has to be set off by different kinds of stimulation and if you modify the kinds of stimulation say horizontal lines instead of vertical lines it will affect the way the visual system develops. That's pretty much like language"

Right but that article still seemed to not mention other terms (not proper names or natural kinds) as being an outcome of that theory. It seems to always be mentioned in conjunction with proper names et al. I am not sure if it has been explicitly broadened to all terms. — schopenhauer1

The article, linked here, discusses the causal theory of names as regards abstract objects.

"For example, the numeral ‘17’ is a name of the number 17. But how can there be a causal relation between a number and subsequent uses of a numeral? In short, how can abstract objects stand in causal relations? It would seem that it is always something concrete that is a cause. In this kind of case, it makes more sense to trace the causal chain back to the dubbing, rather than to the object. For although 17 is an abstract object, the act of dubbing it (first performed by some mathematician, no doubt) was a concrete event that can stand in causal relations to subsequent events."

Whether the process is a Performative Act or baptism, the question remains, what authority has determined that "a triangle is a plane figure with three straight sides and three angles", and why do we accept this. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsOne thing I am pretty sure he is saying is that concept formation is a separate issue than his generative grammar.................A natural reaction might also be to question why he so easily separates these two — schopenhauer1

Chomsky refers to concepts, thoughts and language in Noam Chomsky on the Big Questions (Part 4) Closer To Truth Chats

He says that the relation between thought and language is one of identity

2min - "Language and thought are intimately related . Language has historically be called audible thought , its the mechanism for constructing thoughts over an infinite range which we can then access and use in our various activities"

He says that concepts cannot exist without language

7min - "Even the simplest concepts tree desk person dog, what ever you want , even these are extremely complex in their internal structure . If such concepts had developed in proto human history when there was no language they would have been useless. They would have been an accident if developed and quickly lost as you cannot do anything with them. So the chances are very strong that the concepts developed within human history at a point where we had computational systems which satisfy the basic property"

He says that communication is a secondary use of language, the primary use of language is thought

16min - "Sometimes language is used for communication, but that is a very peripheral use . Almost all our use of language goes on all our waking hours , most of our language is just thinking, we can't just stop , it almost impossible to stop . it takes an incredible act of will to stop thinking"

IE, Chomsky is saying that concepts wouldn't exist without language, and the main function of language is to have thoughts.

Am I mistaken or was Kripke only accounting for meaning in regards to proper names and scientific kinds (like water is H20) which unlike other terms, are always true in all possible worlds? — schopenhauer1

True, I agree that Kripke limited his causal theory of reference to proper names. Putnam extended the theory to other sorts of terms, such as water, whereas in general the theory may be used for many referring terms.

From Wikipedia Causal Theory of Reference:

A causal theory of reference or historical chain theory of reference is a theory of how terms acquire specific referents based on evidence. Such theories have been used to describe many referring terms, particularly logical terms, proper names, and natural kind terms.

In lectures later published as Naming and Necessity, Kripke provided a rough outline of his causal theory of reference for names.......... Although he refused to explicitly endorse such a theory.

The same motivations apply to causal theories in regard to other sorts of terms. Putnam, for instance, attempted to establish that 'water' refers rigidly to the stuff that we do in fact call 'water', to the exclusion of any possible identical water-like substance for which we have no causal connection. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsThe relevant equivalence is not between "triangle" and "three-sided shape", since we might have given some other name to three-sided shapes. The relevant equivalence is between polygons with three sides and polygons, the internal angles of which sum to 180º. This could not have been otherwise. It is not a result of a performative. — Banno

1) In Euclidian space, there is equivalence between (a polygon with three sides)

and (polygons, the internal angles of which sum to 180 deg), and this could not be otherwise.

2) In Riemannian space, there is no necessary equivalence between (a polygon with three sides) and (polygons, the internal angles of which sum to 180 deg), and this could not be otherwise.

3) In RussellianA space, there is equivalence between (a polygon with three sides)

and (polygons, the internal angles of which sum to 75 deg), and this could not be otherwise.

Each space is the result of a Performative Act, first by Euclid, then by Riemann and then by RussellA.

The issue is if a statement can be true in virtue of the meaning of the words alone. But we do not have a consensus on what the meaning of the words means. — Banno

True, there is never an absolute consensus as to what words mean, and words change their meaning with time. But if there was no consensus at all as to the meaning of words, this thread would not be possible, as no one would be able to understand what anyone else was saying.

Words may change, but Kripke's Causal Theory of Reference illustrates the importance of the Performative Act Of Naming in Language in ensuring the stability of language, whereby the reference of a linguistic expression, what it designates in the world, is fixed by an act of “initial baptism”.

Drawing on Gottlob Frege’s distinction between word meaning and word reference, Kripke and Putnam developed a causal theory of reference to explain how words can change while still designating the same thing in reality.

The act of baptism designates a very real physical object associated with something observable. But words may evolve with time, and what establishes the “reality” of an expression is the existence of a continuous causal chain, linked back to the initial baptism.

Language thus maintains a stable relationship with the external environment, ensuring that even though words may change, the expression as a whole remains truthful.

The initial baptism establishes the analytic nature of an expression. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsChomsky doesn’t seem to know if there is a conceptual apparatus so apparently that aspect isn’t part of his LAD? — schopenhauer1

Being able to see the colour red and being able to see a link based on constant conjunction,

as inherent functions of the structure of the brain, and products of genetic coding, are possible without the need of conscious a priori concepts of red or constant conjunction. Concepts are subsequent to the event. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts................My suspicion is that your account is based on considering only one type of analytic statement.. — Banno

Your example may be reworded as: "a triangle is a plane figure, a polygon, where the sum of the internal angles is 180 deg", thereby defining "a triangle".

This is a complex concept, so can be carried out in a straightforward Performative Act of Naming, where one word is defined as a set of other words. This is a purely linguistic process, not requiring any link from word to world, and not requiring any link from linguistic to extralinguistic.

Where do "Gavagai", the inscrutability of reference and the indeterminacy of translation fit in this account? — Banno

The gavagai problem may be solved by taking into account the fact that there are simple and complex concepts, and these must be treated differently. In language, first there is the naming of simple concepts, and only then can complex concepts be named, such as the complex concept "gavagai".

Simple concepts include things such as the colour red, a bitter taste, a straight line, etc, and complex concepts include things such as mountains, despair, houses, governments, etc.

For complex concepts, the "gavagai" may be named in a Performative Act of Naming, such that "a gavagai is a gregarious burrowing plant-eating mammal, with long ears, long hind legs, and a short tail". One word is linked to other words, the linguistic is linked with the linguistic, not the world. Misunderstanding and doubt are minimised in a relatively simple process. As "a gavagai" is defined as having long ears, the statement "a gavagai has long ears" is analytic.

For simple concepts, the process is more complicated. The problem is that of linking a word to something in the world, linking the linguistic with the extra-linguistic. For example the colour "orange" is something that is orange, where one word is linked with one thing in the world

In order to explain the naming of simple concepts, I return to my diagram illustrating naming using Hume's constant conjunction of events, whereby learning a name is more an iterative process that is unlikely to be achieved at the first attempt. One needs to note that from the viewpoint of the observer, both the words and pictures are objects, things existing in the world, where the word is no less an object than the picture.

The words "nyekundu", "kijani" and "samawati" have been determined during Performative Acts of Naming either by an Institution or users of the language or a combination of both.

You asked before why the observer should necessarily link two objects that happen to be alongside each other. As the tortoise said to Achilles when playing chess, where is the rule that I have to follow the rules. Why should the observer take note of a constant conjunction of events? Because, as life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years on Earth, taking note of a constant conjunction of events has been built into the structure of the brain as a mechanism necessary for survival, something innate and a priori.

Chomsky proposed that a person's ability to use language is innate. Taken from the https://englopedia.com article Innateness theory of language:

Linguistic nativism is a theory that people are born with the knowledge of a language: they acquire language not only through learning. Human language is complex and considered one of the most difficult areas of human cognition. However, despite the complexity of the language, children can accurately learn the language in a short period of time. Moreover, research has shown that language acquisition by children (including the blind and deaf) occurs at ordered developmental stages. This highlights the possibility that humans have an innate ability to acquire language. According to Noam Chomsky, “the speed and accuracy of vocabulary acquisition do not leave any real alternative to the conclusion that the child somehow possesses the concepts available before the language experience, and basically memorizes the labels for the concepts that are already part of him or her. conceptual apparatus “

In summary, first, complex concepts may be learnt as a set of simpler concepts in a Performative act of Naming, linking the linguistic to the linguistic. Second, simple concepts may be learnt by linking two objects in the world using Hume's constant conjunction of events, an innate ability having evolved over 3.7 billion years. The first object a name established during a Performative Act and the second object a picture, thereby linking the linguistic with the extralinguistic.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum