Comments

-

Is there an external material world ?

Ah but then your usage of "sensations" implies picture-type qualities inside. Mine didn't.

I meant, brain activity is acts of perception.

But still yes: brain activity isn't and doesn't produce sensations in your sense. -

Is there an external material world ?Are you saying that we don't have qualitative experiences? — Michael

Yes if that means having pictures (or qualities) inside as well as outside.

No if it means experiencing changes in perceptual readiness, i.e. learning.

That brain activity doesn't produce sensations? — Michael

Yes. What's wrong with: brain activity is sensations? -

Is there an external material world ?the what we see in the second sense — Michael

is the myth, the internal picture that doesn't happen.

What happens is a readiness to order and classify and predict, along any number of respects or dimensions.

Does that apple have the colour we see it to have — Michael

Does it belong where we are inclined to place it in our colour scheme?

Sure, that's not a reasonable (direct) question, but neither is (the indirect one), does that apple belong on the same rung of our colour scheme as our sensation of the apple? -

Is there an external material world ?Not everyone can do that. The inability is called aphantasia. — Tate

Not everyone can distinguish fact from fiction. But that inability is quite normal. In perception, it manifests as the mental image myth. (Leading to the binding problem.)

If I see a rock through a TV screen then I'm seeing a rock, but I'm seeing it indirectly. — Michael

The trouble is, 'indirect' is too suggestive of two or more 'directs'. Would it help to say 'non-direct'?

Someone contesting indirect realism doesn't necessarily want to claim that knowledge about the rock flows specifically from the rock to the person. It might result rather from the vast network of interactions and interpretations in the background.

Someone contesting direct realism doesn't necessarily want to claim that knowledge about the rock flows specifically from rock to TV screen to person. It might result rather from the vast network of interactions and interpretations in the background.

aphantasia

Didn't they have a hit with "John Wayne is big leggy"? -

Is there an external material world ?they come from your imagination. — Marchesk

So they are fictional, like characters in a fictional story? They don't literally exist?

Good. But likewise, also, arguably, the so-called images alleged to occur when you are fully (rather than preparing or rehearsing for) using your eyes. -

Is there an external material world ?I do wonder though, what is visualization if it's not "pictures in the head"? — Marchesk

Using your eyes.

Or preparing to. -

Is there an external material world ?Even the naked eye is a middle-man between the external world object and the brain/mental experience. — Michael

Pictures in the head. Where would philosophy be without them? -

Welcome Robot OverlordsYes. — Isaac

Then drop the causation and correlation talk. Was my point. It makes dualists think you recognise a second res. -

Welcome Robot OverlordsAnd my point was just that neuro-physiologists are unwitting dualists when they quite unnecessarily call a spade the cause or correlate of a spade.

-

Welcome Robot OverlordsYou reminded me of that very thing not two posts back. — Isaac

But you retracted.

So, anyway. You do believe (that it is accurate enough to say) that

such memory logging is consciousness. — bongo fury

? -

Welcome Robot OverlordsIf I say 'a race' is lots of runners all starting simultaneously and aiming for the same line, then an answer to the question 'what causes a race?' might be "a load of runners, a finish line, and a starting pistol going off". Put those three things together, you'll have a race. — Isaac

But you said what a race is. Have you said what consciousness is? -

Welcome Robot OverlordsI suppose it would be more accurate to have said [...] cause consciousness. — Isaac

Why? -

Welcome Robot OverlordsPersonally, I believe memory logging of higher order Bayesian (or Bayesian-like) inferences is what causes consciousness. — Isaac

I thought you believed that such memory logging is consciousness. -

Does anyone know the name of this concept?Anti-difference-of-degree-ism — emancipate

Or anti-binary-ism. The implication being, usually, that everything is relative. E.g.

“but everyone is selfish”. — Skalidris

meaning "well obviously, but how selfish?".

Edit: Although, by "selfish" Skalidris already meant "too selfish", which is why they are probably right that "but everyone is selfish" is annoying. -

Does anyone know the name of this concept?Yes, it's getting closer. — Skalidris

Everything's closer. -

Does nothingness exist?

-

"What is it like." Nagel. What does "like" mean?the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that there is something it is like to be that organism. — Nagel

Choose:

the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that the organism sees some aspects of its environment and not others.

or

the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that the organism sees some kinds of picture in its Cartesian theatre and not others. -

The Supernatural and plausibilityI assume that the reader is familiar with the idea of extrasensory perception, and the meaning of the four items of it, viz., telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psychokinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas. How we should like to discredit them! Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming. — Turing, 1950

-

The ChurchlandsCan digital computation produce consciousness? No, because digital computation is an observer-dependent phenomenon, while consciousness is observer-independent. — Daemon

A proper semantics, such as the Chinese Room lacks, is a game of pretend: the pretending of appropriate connections, between words and things, and between tokens of the "same" word. And it depends on observers, because it's in the nature of an act of pretending that there can't be any inherent and un-observed connections between the act itself (the brain shiver) and any of its many plausible interpretations.

And if semantics is observer-dependent, perhaps consciousness is what we call the fleeting (or more persistent) occasions of forgetting that it was all pretend. It's an aspect of our pretending, and hence observer-dependent as well.

The Chinese Room lacks the skills to play the game, and other players may or may not discover that it isn't really joining in. It doesn't understand. It depends, like an abacus, on the involvement of the skilled players, to perform its computations, or conversations. They have to do the pretending of appropriate connections, between words and things, and between tokens of the "same" word. So, lacking the skills, the Room lacks the confusion we call consciousness.

But it isn't obvious that the Room's limitations result from its digital machinery: that it couldn't be enhanced so as to be able to learn to pretend. Some way down the line. -

Metaphysics of Reason/Logicthe reality of X or any of its properties — javra

Properties and relations are where correspondence gets too grand for me. They are too much like verbs and adjectives to be plausible as contenders for ontological commitment along with X, Y and Z. And they aren't required for asserting truths about X, Y and Z. -

What is information?But isn't the information encoded in a message only one part of what is really an indivisible, overarching entity, the conversation? — Pantagruel

Like the "self-information" or "information content" (surprise value of an individual message) is relative to the overarching "information entropy" (average surprise value in a whole source or channel of messages)?

Or are you merely surprised (or informed!) that the theory equates surprise value with information? -

Metaphysics of Reason/Logic

-

Institutional Facts: John R. SearleThat the material in my hand has the chemical composition it has does not depend on us, but that the material in my hand is money does. That the Sun is larger than the Earth does not depend on us, but that it is illegal to steal does.

Neither money nor the law is a fiction. — Michael

Are there institutional facts about immaterial or imaginary things? Or is that what would make them fictions? -

Institutional Facts: John R. SearleInstitutional facts aren’t fiction. — Michael

Oh. Are they hallucinations?

How aren't they fiction? Weren't you stressing their lack of correspondence with actual states of affairs? -

Institutional Facts: John R. SearleYes. See above. — Michael

That passage addresses only institutional facts? -

Institutional Facts: John R. Searle[Searle's] distinction between institutional and non-institutional facts, and which things are institutional and non-institutional facts, is one that holds within the framework of an existing language with existing rules and existing meanings that he will accept is a human institution. — Michael

Does it hold outside of such a framework? Are there institutional facts outside of such a framework?

An object becoming a bishop or a combination of letters becoming a word are historical events — RussellA

I disagree. Tanks rolling over a national border is a historical event. A "tank" token's being pointed at one or more tanks (or a "word" token's being pointed at "tank") is a myth, requiring continual reinforcement, itself no less mythical.

Inscrutability of reference, and all that. -

What motivates panpsychism?Please tell me what goes in between unconscious and conscious? — bert1

Er, semi-conscious? -

What is metaphysics?I do not say mind is physical or non-physical. — Jackson

Do you say that any things are non-physical? -

An Argument Against Sider’s Hell and VaguenessHi there, aka @TheMadFool.

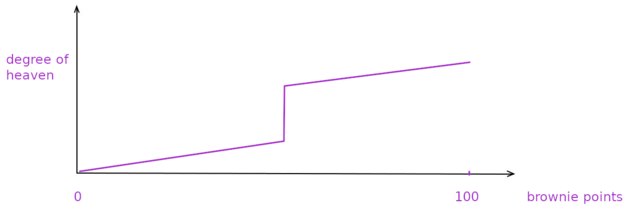

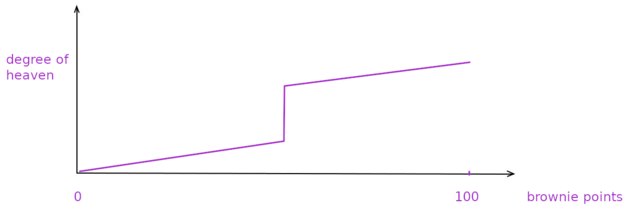

a net ethical point of +1 and I get my ticket to paradise. Someone else who has [...] a net ethical point of -6 and goes to jahanam. — Agent Smith

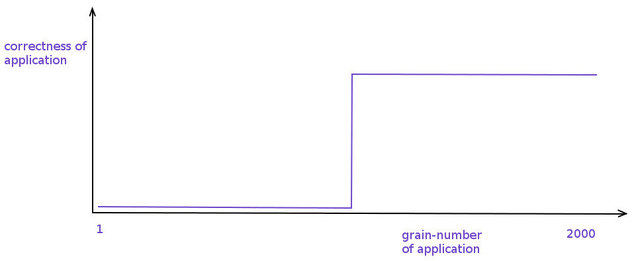

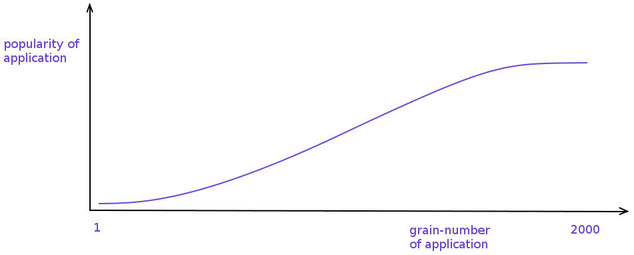

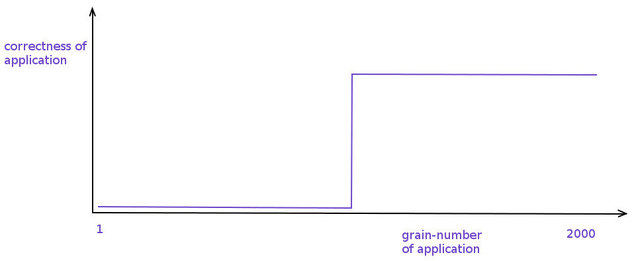

Your suggestion is described by this fourth graph,

from here, https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/560730

(putting net ethical score horizontal and resulting degree of heaven vertical).

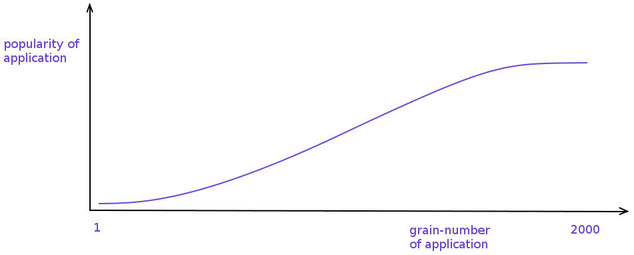

Whereas the OP appears to favour the second graph:

(with the same re-labelling).

I wonder what happens to a person with a net ethical point of cipher/zero? — Agent Smith

Are you switching to grades of hell/heaven after all? You might want some composite of the two graphs. Gradual increase interrupted by a sudden step change.

-

An Argument Against Sider’s Hell and VaguenessWhile this is a small bullet to bite, — lish

It is? Then one wants to ask, is the location of the consequently fine line between least best heaven and least worst hell anywhere special? Or is it arbitrary?

Might you not as well say, hellishness and heavenliness are reciprocal terms ordering all individual afterlives into a line? All afterlives would be in heaven as well as hell in some degree: the most heavenly is simply the least hellish? "Everything is relative, and on a spectrum"? As in line [2] here:

[1] Tell me, do you think that a single grain of wheat is a heap?

[2] Well, certainly, it's the very smallest size of heap.

Game over. People often finish up claiming 2 had been their position all along. Perhaps it should have been, and the puzzle is a fraud. — bongo fury

Or would needing to place the very worst person into even the least grade of heaven be unacceptable, so that you would need to reserve some small corner of hell as heavenly in zero degree? Then your problem, potentially, is to identify a tipping point (e.g. between zero degree heavenly and non-zero degree heavenly) as I say. And then at least the game gets started...

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/562851

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/355842 -

What is metaphysics?Briefly this is Russell's way of saying that science does not even define what physicality is: — Jackson

Sure. A physicalist has no objection to that. Metaphysics as the philosophy of physics.

But your example was

If all my thoughts are physical, — Jackson

Which appears to argue for the non-physics of mind. -

What is metaphysics?Even Bertrand Russell admitted that the very definition of matter was incoherent. — Jackson

I don't think he meant to posit the existence of non-physical stuff. Do you? -

What is metaphysics?I know there is a physical world. I hardly think that explains reality. — Jackson

But do you think positing non-physical stuff will help?

bongo fury

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum